Introduction

The estimate for the number of species currently at risk of extinction is c. 1 million species, and this predicted loss is expected to have catastrophic ecological and economic implications (Ceballos & Ehrlich Reference Ceballos and Ehrlich2002, Cardinale et al. Reference Cardinale, Duffy, Gonzalez, Hooper, Perrings and Venail2012, UN 2019). In light of increasing resource demands, large-scale infrastructure development, extractive enterprises and even private corporations are likely to exert substantial influence on our ability to avert the projected biodiversity crises and, ultimately, to meet biodiversity goals and targets (Lees et al. Reference Lees, Attwood, Barlow and Phalan2020). Given the evidence of ongoing conflicts between economic activities and conservation (Laurence Reference Laurence2019, Sivaraman Reference Sivaraman2019, Teo et al. Reference Teo, Lechner, Walton, Chan, Cheshmehzangi and Tan-Mullins2019), there is considerable opportunity to strengthen and expand corporate conservation policy and collaboration (Addison et al. Reference Addison, Bull and Milner-Gulland2019, Smith et al. Reference Smith, Paavola and Holmes2019, Thompson Reference Thompson2019, Percival & Zhang Reference Percival and Zhang2020).

Corporate initiatives can have a significant moral and practical impact and large spatial footprints in conserving biodiversity (Overbeek et al. Reference Overbeek, Harms and Van Den Burg2013, Smith et al. Reference Smith, Paavola and Holmes2019). However, at present, a minority of companies implement formal biodiversity or conservation-related programmes, and a majority of companies do not report or release information about their practices or performance regarding species/habitat loss or extinction (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria Reference Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria2017, Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Hassan, Elamer and Nandy2021). Furthermore, academic research is scarce on conservation-related disclosures and corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting from large corporations and transnational operations as they relate to biodiversity protection, mitigation, restoration and protection (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Mansi and Pandey2018, Addison et al. Reference Addison, Bull and Milner-Gulland2019, Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Hassan, Elamer and Nandy2021). Biodiversity accountability studies reveal that there is often limited information provided publicly by companies, especially large corporations involved in biodiversity loss and threats (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria Reference Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria2017). Yet there has been progress in developing corporate biodiversity reporting guidelines to assess biodiversity risks and integrate corporate sustainability and accountability (Samkin et al. Reference Samkin, Schneider and Tappin2014, Addison et al. Reference Addison, Stephenson, Bull, Carbone, Burgman and Burgass2020). With the emergence of biodiversity reporting frameworks, there is a growing ability to evaluate and assess corporate environmental performance for companies involved in large-scale developments and resource extraction projects.

China has become a key player in international development projects as the most prominent emerging economy globally. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR), established in 2013, is an ambitious economic development plan to connect China globally to Africa, Europe, Southeast Asia and South America through trade and other networks. The BRI encompasses an overland ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and an ocean ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’. As of 2020, the BRI involved 141 countries with projects related to the development and financed infrastructure improvements (Fig. 1). As a result, the BRI invests in extensive infrastructure development in many developing countries through networks of Chinese state-owned companies and private Chinese small or medium-sized firms.

Fig. 1. A map illustrating the Belt and Road Initiative roads, rail network and pipelines and the global reach of Chinese-funded investments for infrastructure and development corridors.

Existing data suggest that there are widespread negative environmental conflicts associated with BRI projects (Ascensão et al. Reference Ascensão, Fahrig, Clevenger, Corlett, Jaeger, Laurance and Pereira2018, Hughes Reference Hughes2019, Losos et al. Reference Losos, Pfaff and Monday2019, Teo et al. Reference Teo, Lechner, Walton, Chan, Cheshmehzangi and Tan-Mullins2019, Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Lechner, Chitov, Horstmann, Hinsley and Tritto2020, Narain et al. Reference Narain, Maron, Teo, Hussey and Lechner2020), including habitat loss, as new roads and developments open up previously inaccessible areas to logging, mining and land conversions (Hughes Reference Hughes2019, Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Lechner, Chitov, Horstmann, Hinsley and Tritto2020). Increasing transportation infrastructure and resource extraction in BRI projects in remote regions and ecosystems, especially within developing, tropical regions with high levels of biodiversity (Lechner et al. Reference Lechner, Chan and Campos-Arceiz2018), have led to documented deforestation, habitat fragmentation (Ibisch et al. Reference Ibisch, Hoffmann, Kreft, Pe’er, Kati and Biber-Freudenberger2016, Losos et al. Reference Losos, Pfaff and Monday2019) and current and projected population loss of endangered large mammals (Nabi et al. Reference Nabi, Khan, Ahmad, Khan and Siddique2017, Tracy et al. Reference Tracy, Shvarts, Simonov and Babenko2017, Ascensão et al. Reference Ascensão, Fahrig, Clevenger, Corlett, Jaeger, Laurance and Pereira2018, Laurance et al. Reference Laurance, Wich, Onrizal, Fredriksson, Usher and Santika2020, Liu et al. Reference Liu, Yong, Choi and Gibson2020, Ng et al. Reference Ng, Campos-Arceiz, Sloan, Hughes, Tiang, Li and Lechner2020). Several reports identify the impacts of BRI infrastructure developments on terrestrial and marine wildlife (WWF 2018, Turschwell et al. Reference Turschwell, Brown, Pearson and Connolly2020), and several comprehensive regional studies identify where future infrastructure operations associated with BRI projects affect highly biodiverse regions as well as protected areas and species (Alamgir et al. Reference Alamgir, Campbell, Sloan, Goosem, Clements, Mahmoud and Laurance2017, Nabi et al. Reference Nabi, Khan, Ahmad, Khan and Siddique2017, Hughes Reference Hughes2019, Lashari et al. Reference Lashari, Li, Hassan, Nabi, Rashid, Mabey and Islam2019, Sloan et al. Reference Sloan, Bertzky and Laurance2017, Reference Sloan, Campbell, Alamgir, Engert, Ishida and Senn2019a, Reference Sloan, Campbell, Alamgir, Lechner, Engert and Laurance2019b, Ng et al. Reference Ng, Campos-Arceiz, Sloan, Hughes, Tiang, Li and Lechner2020, Plumptre et al. Reference Plumptre, Ayebare, Kujirakwinja and Segan2021).

There have been several reviews of corporate responsibility along the BRI, citing specific and comprehensive legal frameworks to encourage companies towards responsible behaviour (Xiheng Reference Xiheng2019, Lu Reference Lu2020, Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wong, Yuen and Li2020, Zhao & Atkins Reference Zhao and Atkins2021). However, no specific research is available concerning biodiversity-related environmental responsibility reporting for Chinese companies participating in the BRI. In this study, we explore corporate accountability structures for the BRI’s largest corporations and assess the current status of biodiversity conservation-related metrics. The objectives of this study are: (1) to review the overarching environmental sustainability policies and CSR regulations for the companies participating in the BRI; (2) to evaluate corporate responsibility environmental, social and governance (ESG) financial data with regards to biodiversity conservation; and (3) to discuss opportunities for addressing the biodiversity impacts of the BRI through reporting initiatives. This evaluation provides insight into how the BRI’s largest corporations and companies align with a sustainability vision for biodiversity conservation and the current status of CSR disclosure for biodiversity in BRI projects, and it also provides information on opportunities and avenues to strengthen conservation compatibility in BRI projects.

Policy review and background

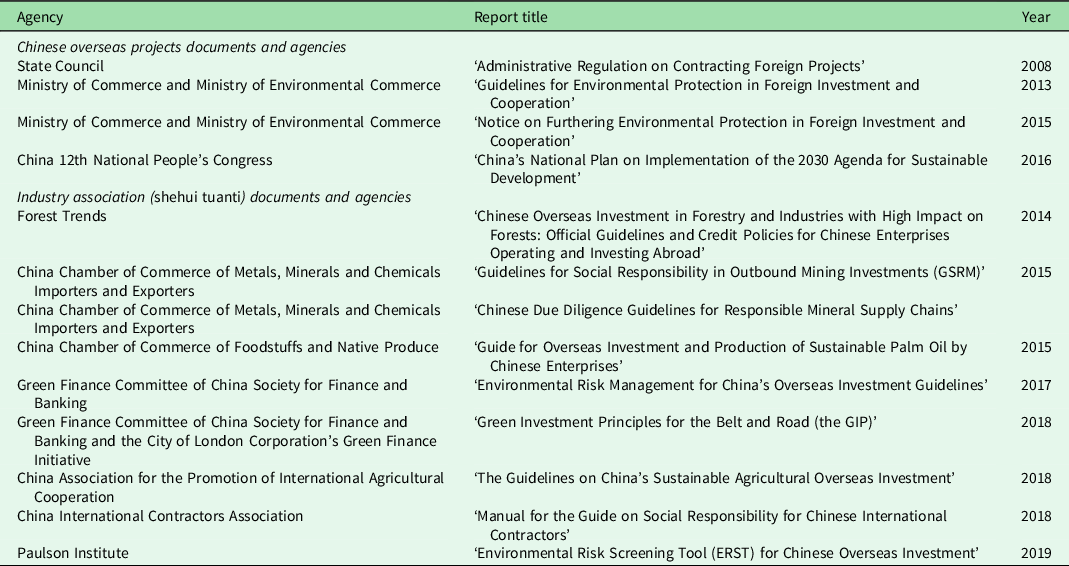

There is little precedence for addressing the multiple and cumulative impacts of infrastructure development or regulating transnational environmental accountability at the scale of the BRI (Percival & Zhang Reference Percival and Zhang2020). The BRI has set firm commitments to environmentally friendly development principles and approaches with numerous government-issued documents and non-governmental organization (NGO) recommendations (Table 1). In 2017, largely in response to growing concerns over the environmental news and reputation of the BRI, President Xi called for the development of a Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition (BRIGC) as a consortium to invite communication between 20 United Nations programmes and 134 national and national partners from various environmental ministries in BRI countries around the world, academic institutes, international organizations and businesses (Li Reference Li2019, Pike Reference Pike2019). Alongside the BRIGC network, the China NGO Network for International Exchanges proposed to build a Silk Road NGO Cooperation Network, involving 310 organizations covering 69 countries. It has since become an essential platform for NGOs. Data-sharing platforms for ‘big data’ information are being developed that international agencies, governments and NGOs can use to address the key social, political and environmental dimensions of the BRI (Teo et al. Reference Teo, Lechner, Walton, Chan, Cheshmehzangi and Tan-Mullins2019). Environmental transparency has also been outlined in the ‘Guidelines on Greening BRI’ document, which calls for public participation and environmental information disclosure (Shvarts et al. Reference Shvarts, Simonov, Cheremeteff, Broekhoven, Khmeleva and Dolinina2018). In addition, there have been significant advances in Chinese domestic governance mechanisms to provide disclosure of a broad range of information, such as environmental, contractual, financial and construction information, under the 2007 State Council Regulations on Open Government Information (OGI) (Horsley Reference Horsley2018). Chinese government agencies have been releasing some 30–40 million records annually, and 57 central government departments recorded a total of nearly 150 000 information requests filed in 2015 (Horsley Reference Horsley2016). Most recently, the BRIGC has published the ‘Green Development Guidance for BRI Projects Baseline Study Report’, containing extensive recommendations for best practices and calling to establish an environmental risk classification system to rank projects according to pollution prevention, climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation-related objectives (BRIGC 2020).

Table 1. List of Chinese government- and international non-governmental organization-issued documents pertaining to environmental protection across the Belt and Road Initiative.

These policy instruments are designed to encourage companies to perform responsibly and sustainably to achieve ecological civilization (Lu Reference Lu2020, Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wang, Liu and Huang2020). However, the desire for foreign investment to fund critical infrastructure such as roads, rail networks, oil refineries, hydropower stations or power plants in less developed countries can lead to less ambitious local and regional environmental impact assessment (EIA) regulations to attract such investment (Aung et al. Reference Aung, Fischer and Shengji2020). The environmental legislation within China remains primarily enforced by local governments, as the governmental system in China is decentralized, so enforcement is weaker. There are few legal ramifications for not adhering to many of the environmental goals and commitments to conserving biodiversity along the BRI. An essential document that China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment published in 2017 entitled ‘Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road’ makes wide-ranging commitments to develop environmental protection cooperation mechanisms and to improve on the international environmental governance system, as well as to manage bilateral and multilateral international cooperation mechanisms for environmental protection. Given these directives and the overarching need for Chinese companies to adhere to regional and national laws, Shvarts et al. (Reference Shvarts, Simonov, Cheremeteff, Broekhoven, Khmeleva and Dolinina2018) showed that overlapping multilateral environmental agreements of BRI countries have uneven involvement in global governance programmes. Shvarts et al. (Reference Shvarts, Simonov, Cheremeteff, Broekhoven, Khmeleva and Dolinina2018) highlight gaps in adherence to the principle of protecting environmental resources from exploitation as directed by BRI documents, and they argue that this is due to the absence, in many places, of international- or national-level conservation policy enforcement.

Domestically, China has been proactive in responding to external corporate environmental responsibility pressures in areas such as renewable energy, but it has had less environmental awareness in overseas investments. In projects with developing countries where infrastructure is limited, strategic environmental assessments or EIAs are not required (Tracy et al. Reference Tracy, Shvarts, Simonov and Babenko2017). There are policy gaps overseas for the BRI related to EIAs at the level and standard that China employs domestically for development and investment (Aung et al. Reference Aung, Fischer and Shengji2020). Since these companies are not required to adhere to China’s EIA system when operating abroad, they are not bound to this performance legally. China’s EIA system is more comprehensive than similar systems in all other BRI participating countries, highlighting the need for policies that can support sustainability with limited local or regional policy architecture (Tracy et al. Reference Tracy, Shvarts, Simonov and Babenko2017, Aung et al. Reference Aung, Fischer and Shengji2020).

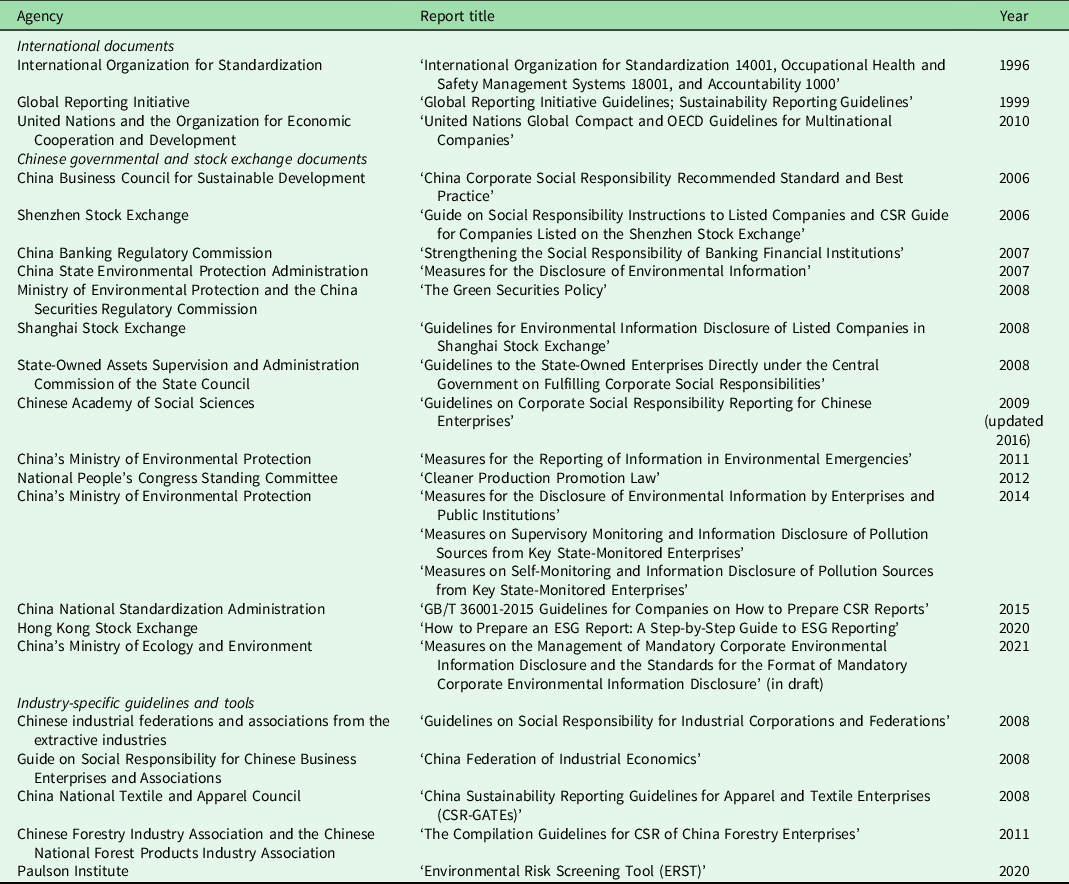

In China, environmental NGOs (non-profit enterprises, social groups, social service organizations and foundations) operate with strong formal and informal ties to the government and are subject to the standards of Chinese policies and government documents; therefore, the concept of the NGO in China is different from that in the Western conceptualization (Guttman et al. 2018). Hybrid governance arrangements are often the driving forces behind corporate environmental change and pressure for pro-environmental politics and governance. For example, they integrate influential non-state actors and NGOs, who hold different perspectives on international norms, into business activities and development planning projects (Ongaro et al. Reference Ongaro, Gong and Jing2019). The shehui tuanti (‘social associations’) serve as business associations and NGOs that have developed numerous industry guidelines (Table 2) regarding voluntary sustainability standards (Zhang Reference Zhang2021) for Chinese overseas governance over a variety of materials and contexts. Compliance with voluntary sustainability standards can be accredited by international certification companies such as Standards Technical Service Co., Ltd, which can monitor or audit degrees of compliance (Zhang Reference Zhang2021).

Table 2. Documents on Chinese overseas investments from the Chinese government and industry or shehui tuanti (‘social associations’).

Reporting environmental impacts and disclosing CSR information related to sustainability is encouraged, and in many cases required, by various environmental governance and sustainability certification agencies. Since CSR disclosure has become more accepted globally, specific policy and regulatory documents have been produced for Chinese companies, sectors and stock exchanges (Table 3). On a global scale, the Global Reporting Initiative has been promoted and recognized by the United Nations Environment Programme; however, companies still lack proper biodiversity reporting guidance, with these directives having been critiqued as too broad or vague (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Hassan, Elamer and Nandy2021). Within China, there has been a concerted effort by the Chinese government, stock exchanges and regulators to provide corporate environmental responsibility policies and guidelines for corporations, where state-led efforts are the driving force for companies to endorse these reporting initiatives in contrast to ‘societal’ or external pressures to maintain social acceptance or corporate reputation (Lu Reference Lu2020). The China State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA; currently merged into the Ministry of Ecology and Environment) first offered legal documents in 2007, which required central government organizations to disclose environmental pollution and report any specific operations regarding environmental protection. Then, the Shanghai Stock Exchange made its directives mandatory in 2008, resulting in a significant increase in Chinese companies producing sustainability reports. However, the frameworks have been critiqued as too vague or broad for companies and lacking in verification, legitimacy or rigour (International Finance Corporation 2011). In 2021, China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment drafted their new Mandatory Environmental Information Disclosure System Reform Plan, which addresses outstanding issues specifically regarding the information required for disclosure of environmental information. The new types of mandatory disclosure include: annual disclosure for nine types of information directly related to environmental management, pollutant discharge, pollution measures and carbon emissions; and detailed disclosure of any violations of ecological and environmental regulations. Specific to the BRI, the Paulson Institute has developed an Environmental Risk Screening Tool (ERST) for Chinese overseas investment that allows regulators and institutions to use a spatial platform to assess projects with high environmental impacts and risks. Overall, these commitments made in corporate responsibility statements and best practice commitments may constitute evidence in court to show that a company’s standards are reasonable and should be followed, especially for a company incorporated in local jurisdictions (Greenfield Reference Greenfield2013).

Table 3. Documents on corporate responsibility reporting specifically regarding environmental, social and governance (ESG) guidelines.

CSR = corporate social responsibility.

Methods

We collected Chinese company information from two sources: Refinitiv Eikon BRI Connect and the China Global Investment Tracker. The Refinitiv Eikon BRI Connect app, a global provider of financial market data, lists 3869 companies that participate in the BRI. Of those, 1529 were Chinese companies, of which 112 are listed on various stock markets, mainly the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges. The China Global Investment Tracker, compiled by the American Enterprise Institute and The Heritage Foundation, is a public dataset on Chinese companies with investments of >US$100 million (American Enterprise Institute 2020). The database lists 312 companies that participate in BRI projects, and from those, 184 companies are listed on stock markets, mainly on the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges. These two lists were combined and filtered for duplicates, producing 260 of the largest companies involved in BRI projects. By selecting large companies listed on stock exchanges, we are biasing our data towards business leaders and companies more concerned with ESG metrics because they are more susceptible to public criticism. As such, this probably represents an overestimation of the attention paid to biodiversity issues by all Chinese companies.

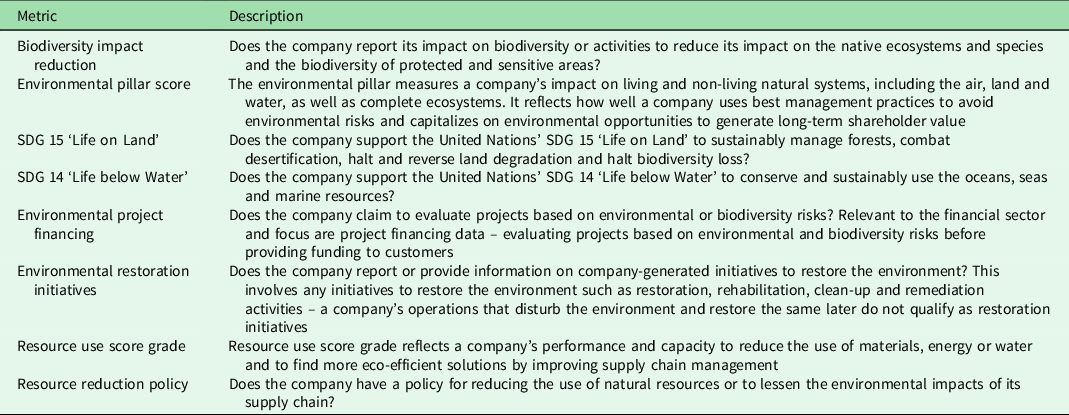

The global financial sector has resources for evaluating corporate responsibility for environmental resources and biodiversity conservation (UN Environment Programme et al. 2020). Standard tools are available for rating companies according to ESG metrics in order to measure sustainability impacts, and these are intended to be included in financial decision-making. The ESG metrics chosen for this study to represent biodiversity reporting include measures for biodiversity impacts, environmental financing, environmental restoration mitigation and support of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to evaluate a company’s responsibility and performance, and we also included supply chain-related resource use for comparison purposes. Our research is based on third-party-generated metrics to understand biodiversity risk management and environmental accountability, as research suggests a positive, realistic link between company information in sustainability reports and third-party ratings (Papoutsi & Sodhi Reference Papoutsi and Sodhi2020).

The ESG data for each company are generated by content research analysts at Refinitiv Eikon using publicly available information sources (Refinitiv 2020). These data represent some of the most comprehensive metrics available for ESG reporting. Each company is screened independently. The information for the ESG reports is collected once a year based on a company’s CSR reports, annual reports, websites, registration reports, financial statements, reference documents, Global Reporting Initiative reports, DEF14-Proxy statements, Audit Committee Charter, Bylaws, Constitution corporate governance guidelines and reports, code of conduct reports, Notice of Annual Meetings and NGO reports such as those of Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. The process has over 400 built-in error checks, screenings or detailed audits by over 150 analysts who seek to provide objective and binary data collection standards in order to produce clean, high-quality data. Records are refreshed every 2 weeks based on computed quality generators, such as checking news for controversies related to the environment. The ESG and related metrics were extracted from Refinitiv Eikon via the Eikon Python API (downloaded on the week of 12 January 2021).

For this study, Chinese companies were evaluated in terms of eight ESG factors directly related to corporate accountability for biodiversity conservation (Table 4). These were selected out of a pool of over 450 metrics related to ESG that directly pertained to biodiversity goals or actions that a company can take that would impact environmental quality. There were also binary indicators for the support of any of the 17 SDGs, and we focused our analyses on the two SDGs (14 ‘Life in Oceans’ and 15 ‘Life on Land’) that were directly related to biodiversity conservation. We also included two ESG metrics for greening the supply chain and overall company-related environmental policy and natural resource use reduction, as we felt that it was essential to explore general environmental proactivity as a baseline for sustainability company policy. These metrics are generated on self-reporting and voluntary contribution of information about sustainability policies. These metrics do not include any third-party direct measurement of biodiversity impacts on the ground, nor is there any way to verify whether these companies directly take the actions reported by the ESG database. For example, if the binary scores are addressed only to a limited extent by the company, it may be listed as a positive score, regardless of the impact on the environment. The ESG metrics not included in the study include metrics that did not pertain directly to the subjects of biodiversity or sustainability, such as carbon emissions, human rights and shareholders.

Table 4. Environmental, social and governance criteria used to characterize a company’s willingness to assess and act on biodiversity and natural resources conservation.

SDG = Sustainable Development Goal.

Results

There were 260 Chinese companies listed on the Thomson Reuters Eikon stock index, representing a total combined enterprise value of US$32.2 trillion and recording a combined gross profit of US$4.6 trillion. Companies within the study came from various industries, with over half of the companies supplying industrials, basic materials or consumer cyclicals.

Of these 260 companies, 108 respondent companies (42% of our sample) had ESG scoring by Refinitiv Eikon. They had listed the eight listed biodiversity scores and metrics of concern to this study. Furthermore, 151 (58%) companies had no ESG data for any of the eight given categories in our search, as illustrated by the numerous NA (i.e., not available) values, representing companies that did not have such information reported in the database (Fig. 2). Otherwise, companies were given binary indicators of 1 for supporting the goal or 0 for having no policies or showing no progress towards that goal. In the 108 companies with ESG scores, a majority did not report biodiversity impacts (Fig. 2a), did not have environmental project financing (Fig. 2b), did not engage in environmental restoration (Fig. 2c) and did not support UN SDGs 14 and 15 (Fig. 2d & 2e). Only a fraction of companies had ‘high’ environmental pillar scores (Fig. 2g). On the other hand, most companies reported having policies to reduce resource use by greening the supply chain (Fig. 2f). However, a majority had either medium or low resource use scores, indicating a low capacity to support or advance conservation efforts (Fig. 2h).

Fig. 2. Summation of companies participating for each of the eight environmental, social and governance categories. (a) Number of companies who listed whether they report (1) or do not report (0) on activities that impact biodiversity. (b) Number of companies who claim to evaluate projects (1) or not evaluate projects (0) based on environmental or biodiversity risks. (c) Number of companies who claim to provide information (1) or not provide information (0) on initiatives to restore, rehabilitate, clean up and remediate the environment. (d) Number of companies who listed whether they support (1) or do not support (0) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15 ‘Life on Land’. (e) Number of companies who listed whether they support (1) or do not support (0) SDG 14 ‘Life below Water’. (f) Number of companies who have a policy (1) or do not have a policy (0) for reducing the use of natural resources to lessen the environmental impacts of their supply chains. (g) Environmental pillar score, measuring a company’s impact on the environment and how well the company manages risks and uses best management practices: high (66–100), medium (33–33) or low (0–33). (h) Resource use score, reflecting a company’s performance and capacity to find eco-efficiency in its supply chain: high (66–100), medium (33–33) or low (0–33).

Upon investigation of the SDGs in total, information existed for 108 companies, and 31 companies had reported support for at least one of the SDGs, while 76 companies did not report support for any of the SDGs (Table 5). Sixteen companies had reported support of SDG 15 ‘Life on Land’, and 14 companies had reported supported of SDG 14 ‘Life in Water’ (the least supported of all the SDGs). SDGs 14 and 15 were among the top three least supported SDGs.

Table 5. List of the Belt and Road Initiative companies with available data (n = 107) supporting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 8, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Discussion

The evidence from this study suggests that the prominent corporations working on BRI projects have underutilized accountability structures designed to help achieve a balance between large-scale development projects in and adjacent to biodiversity areas. Our analyses revealed that for the 260 companies actively engaged in BRI-related infrastructure developments a majority had tended not to report, finance or engage in actions related to biodiversity risks. Only a small percentage (11%) of our sample evaluated their environmental impacts for environmental project financing. Out of the 108 companies with biodiversity metrics reported, approximately a third voluntarily ranked themselves as having participated in biodiversity-related mitigation and restoration activities, and even fewer identified activities that specifically supported SDGs 14 and 15. This level of adherence to corporate sustainability metrics is notable and shows room for improvement in using these metrics to monitor and align sustainable development in the BRI. The modest fraction of companies using biodiversity accountability metrics also highlights the need to restructure and incentivize corporate accountability for environmental and biodiversity risks.

By contrast to the biodiversity metrics, supply chain information and resource use policies showed more positive results. Nearly all companies had some guidelines for reducing the use of materials, energy or water and sought solutions to improve supply chain management. These general environmental use reduction scores allow us to understand the most basic reach or potentially the minimum environmental policymaking adopted broadly across these organizations. Some policies address resource use reduction and supply chain management, which is very positive. Further research is needed in order to understand how these resource use policies may result in sustainable practices that specifically enhance biodiversity.

Beyond actions taken at the corporate level to improve reporting, this also points to policy gaps that enable companies to ignore their responsibilities to balance economic development with biodiversity conservation. The results imply a lack of engagement with biodiversity-related SDGs 14 and 15, with few companies reporting commitments for economic growth and climate action. Research has recommended that projects integrate with the international frameworks of the SDGs and national and local governments in order to prevent developing countries from sacrificing their natural resources in exchange for economic growth and bypassing environmental protection mechanisms (Yin Reference Yin2019).

More than half of the corporations (58%) showed no ESG metrics, demonstrating that sustainability CSR documentation is not available for most listed BRI companies. Similarly, an evaluation system in China, the ‘GoldenBee Enterprise CSR Practice Evaluation System (2020)’, found that 40% of the top 500 companies in China have not yet issued CSR reports (China WTO Tribune & GoldenBee Management Consulting Co., Ltd n.d.). Previous studies on corporate environmental responsibility along the BRI highlight the nascent stage of development for participating in and reporting environmental impacts, especially when compared to global ratings for sustainability indices and environmental performance (Lu Reference Lu2020).

There has been some research on why Chinese companies do not report and disclose more of their corporate responsibilities. Researchers often use legitimacy theory to relate environmental disclosure directly to more significant public pressure, where companies that show poor economic performance can use disclosure as a tool to explain their performance and demonstrate environmental legitimacy (Cho & Patten Reference Cho and Patten2007); this is also referred to as a communication tool for impression management. The economic market and Chinese bank are closely tied to government politics and oversight in China. A top-down mandated and regulated disclosure system is more likely to urge companies to comply with CSR reporting than a third-party organization or external pressures (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Xu and McIver2021). Research indicates that Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are more likely to perform sustainably in the context of institutional requirements, mainly to secure governmental finance-related support (Meng et al. Reference Meng, Zeng and Tam2013). On the other hand, Chinese companies that are not SOEs are more likely to respond to external international pressures for environmental disclosures because their business survival depends on reputation and legitimacy compared to SOEs backed financially by the Chinese government (Khalid et al. Reference Khalid, Sun, Huang and Su2021). Previous studies have revealed that, overall, CSR disclosure is a function of firm performance and state ownership (Li et al. Reference Li, Luo, Wang and Wu2013). Chinese forestry companies revealed that firm size and equity concentration are positively correlated with CSR disclosure (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Kozak, Toppinen, D’Amato and Wen2017).

Studies have found that environmental disclosures by companies in China have positive benefits, showing decreases in corporate risk by reducing uncertainties between firm–investor information and asset pricing, as well as more effectively managing risk perceptions (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Du and Zeng2021). For example, research on Global Reporting Initiative reporting found a positive impact on firm financial performance when giving a strong signal to stakeholders that CSR reporting is comprehensive, especially for companies with many local political ties (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Orzes, Jia and Chen2021). Conversely, recent examples of pollution disclosure in China indicate that pollution blacklists only have a short-term negative impact on stock market value, which is considered a low environmental penalty that is thought to arise due to weak enforcement of Chinese environmental law (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Cao and Feng2021). We argue that corporate accountability in biodiversity conservation along the BRI will grow as these CSR metrics are more widely adopted and used by giant corporations, allowing investors to consider their contributions to biodiversity and environmental goals when deciding when and where to invest.

Previous studies have shown that, generally, biodiversity is often not seen as a viable option for clear CSR commitments, while global carbon emissions or deforestation targets have been more frequently addressed through environmental accounting (Silva et al. Reference Silva, Regan, Pollard and Addison2019, Addison et al. Reference Addison, Stephenson, Bull, Carbone, Burgman and Burgass2020, Dempsey et al. Reference Dempsey, Martin and Sumaila2020). Part of this may be due to the lack of clear guidelines on how an organization can incorporate biodiversity management, which is a criticism of the Global Reporting Initiative guidelines, in that they are too broad, allowing them to be misinterpreted, or that they lack a comprehensive framework for biodiversity risk reduction or extinction prevention (Maroun & Atkins Reference Maroun and Atkins2018). Revisions of corporate commitments in biodiversity have often focused on species-level or site-level management of biodiversity (e.g., endangered species or ecosystems), as these impacts are most logically and easily managed at the local or regional level. Other studies have researched the specific number of companies developing their internal biodiversity commitments such as no net loss or having a net positive impact on biodiversity, finding that 41 companies globally had made this level of commitment in terms of biodiversity, compared to 400 companies that gave a zero deforestation-type commitment over a similar time period (Silva et al. Reference Silva, Regan, Pollard and Addison2019). Other techniques may seek to measure the level of pressure a company may exert at local and international scales due to the telecoupling effects, where the consumers in international markets adversely impact a region’s biodiversity (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Hull, Luo, Yang, Liu and Viña2015), through a science-based analysis of species abundance and species diversity. Numerous tools and institutional initiatives for corporate responsibility are available to support companies to assess their biodiversity-related risks (Overbeek et al. Reference Overbeek, Harms and Van Den Burg2013, Samkin et al. Reference Samkin, Schneider and Tappin2014, Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria Reference Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria2017, van Zanten & van Tulder Reference van Zanten and van Tulder2018, Smith et al. Reference Smith, Paavola and Holmes2019, Addison et al. Reference Addison, Stephenson, Bull, Carbone, Burgman and Burgass2020, Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Hassan, Elamer and Nandy2021). A high level of ambition in terms of biodiversity accountability commitments has been demonstrated by a subset of large corporations. Companies reporting the actual species counts relating to their developments or business activities increases transparency, where species are considered stakeholders in business activities (Hassan et al. Reference Hassan, Roberts and Rodger2021). Beyond biodiversity accounting, there is a new paradigm of ‘extinction accounting’ frameworks, which are more developed and disclose risks of species extinctions and actions taken for the prevention of such extinctions (Atkins & Maroun Reference Atkins and Maroun2018, Maroun & Atkins Reference Maroun and Atkins2018).

Globally, research into the biodiversity reporting of the top 200 of the Fortune 500 companies obtained sustainability reports on the fine details regarding species numbers impacted by their activities; 25% of companies had reported actual species losses or impacts (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Hassan, Elamer and Nandy2021). Another study investigating the global Fortune 100 companies in 2016 found that only 31 companies had given clearly stated commitments to biodiversity, and only 5 had made commitments that were seen as specific, time-bound or measurable, as compared to sustainability reporting for carbon emissions reductions, where 80% of the world’s top 250 companies committed to carbon emissions reductions in 2015 (Addison et al. Reference Addison, Bull and Milner-Gulland2019). Other studies have also found that over half of the A-list companies in China do not produce sustainability reports that include biodiversity-related reporting initiatives (Zhao & Atkins Reference Zhao and Atkins2021). The process of assessing biodiversity risks and then taking steps to report risks and disclose activities is only a precursor to a more in-depth financial analysis to establish the value of biodiversity and to measure the impacts of a company’s finances on biodiversity (UN Environment Programme et al. 2020).

Future directions

While this study focuses on the most prominent multinational Chinese corporations participating in the BRI, further research on small and medium-sized companies, regardless of nationality, is needed in order to better understand their role outside of China in terms of their effects on environmental and biodiversity goals across the BRI. The companies listed within this study report company-wide behaviour for ESG metrics that are not specific to the BRI projects. For example, the Chinese firms may follow more stringent environmental safeguards domestically and not overseas, where their reporting initiatives may not include multinational operations to meet national reporting regulatory standards.

Finding a balance between biodiversity conservation and significant supranational infrastructure development remains a pressing global challenge. Peer-reviewed academic literature and news reports about biodiversity impacts across the BRI highlight the need for corporate engagement with biodiversity risk management. This study reviews ESG metric scores from companies involved in BRI projects, and the results suggest a currently limited adoption of the existing guidelines to support sustainable development in critical habitats through biodiversity reporting. Our results identify pressing needs for greater corporate environmental responsibility concerning minimizing biodiversity risks across the BRI. Accountability frameworks offer meaningful opportunities and benefits to address the challenge of integrating biodiversity conservation into company performance evaluations. We discuss the complex interplay between international and national corporate accountability structures and review potential reasons as to why these companies may choose to disclose or not disclose their environmental impacts based on these frameworks. This research shows that available international and national policies and frameworks concerned with biodiversity reporting are underutilized. This research is of interest to sustainability and environmental management and NGO groups that provide collaborative guidance for Chinese companies through biodiversity accounting tools and that bridge the gap between corporate performance and conservation science.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are given to the Professional Association of China’s Environment for initial idea generation, especially Dr Hu Tao and his associate Dr Dan Guttman for reflecting on the contents and suggesting research directions. Thanks are given to Dr Elizabeth Losos, who made several reviewer comments about corporate responsibility.

Financial support

This work was partially funded by National Science Foundation Grant CNH-L: People, Place, and Payments in Complex Human-Environment Systems (Award ID 1826839).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

None.