Introduction

Retention is an ongoing and important issue for the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) workforce.Reference Blau and Chapman 1 The costs of replacing EMS professionals include recruitment, selection, and training, as well as “lost productivity” as new EMS professionals catch up to the performance levels of experienced professionals leaving EMS.Reference Gomez-Mejia, Balkin and Cardy 2 The demand for additional EMS workers is expected to increase in the future. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS; Washington, DC USA) projects a need for an additional 62,000 Emergency Medical Technician (EMT)-Basics and Paramedics in the next decade to fill new jobs and replace workers who leave the profession. 3 Given this projected demand, studying why EMT-Basics and Paramedics leave EMS is important, and is the goal of this paper.

General work psychology research has long-acknowledged five types of distinct inter-role work transitions: entry (into the workforce); intracompany (transfer); intercompany (leave organization but remain in profession); interprofession (leave profession); and exit (leave workforce).Reference Louis 4 Patterson et alReference Patterson, Jones and Hubble 5 studied turnover and the cost of turnover by following a convenience sample of 40 EMS agencies over a 6-month period. Results showed a lower-than-expected overall weighted mean annual job turnover rate of 10.7%, with slight variations depending on staff mix. Job turnover rate was measured by combining voluntary quits and involuntary terminations. It is not known if the job leavers also left the EMS profession. Research suggests that it is generally easier to leave one’s job and stay in that profession than to leave one’s job and profession due to the “sunk costs” (eg, education, training, work experience, and disrupted work network) that someone has often invested in his or her occupation/profession.Reference Carson, Carson and Bedeian 6

Prior research has acknowledged the difficulty in collecting actual job and occupational turnover data, so that intent to leave one’s job and/or occupation is often measured as a proxy for actual change.Reference Blau 7 There has been prior study comparing correlates or antecedents of intent to leave one’s job versus occupation across different health-related professions, including medical technologistsReference Blau 8 - Reference Blau, Tatum and Ward-Cook 10 and cancer registrars.Reference Chapman, Blau, Pred and Lindler 11 Across these studies, organizational-context variables (eg, perceived organizational support, reward satisfaction, and laboratory personnel reduction) were generally significantly negatively related to intent to leave one’s job, while occupational-context variables (eg, affective occupational commitment, and general work satisfaction) were negatively related to intent to leave one’s occupation.

Looking at prior Longitudinal EMT Attributes and Demographics Study (LEADS) research comparing intent to leave one’s job versus profession for EMT-Basics versus EMT-Paramedics, Chapman et alReference Chapman, Blau, Pred and Lopez 12 found that perceived health had a significant negative impact on both EMT-Basics’ and EMT-Paramedics’ intent to leave profession (lower health, higher intent) but not intent to leave one’s job. A lower proportion of emergency to scheduled transports had a significant positive impact on both EMT-Basics’ and EMT-Paramedics’ intent to leave their job, but not profession. Extrinsic job satisfaction (eg, pay and benefits, and advancement opportunities) was a significant negative correlate to both intent to leave job and intent to leave profession for EMT-Basics and Paramedics. However, intrinsic satisfaction (eg, variety of tasks, technical challenges, and helping others) was a significant negative correlate only for EMT-Paramedics’ intent to leave the EMS profession. A focus group study of factors contributing to recruitment and retention of EMT-Basics and Paramedics indicated that many interviewees perceived low pay and inadequate benefits but also a strong sense of camaraderie and making a difference in people’s lives.Reference Patterson, Probst, Keith, Corwin and Powell 13 Chapman et alReference Chapman, Blau, Pred and Lopez 12 speculated that if EMT-Paramedics, due to their greater training and increased scope of work than EMT-Basics, have higher expectations for enriched jobs but perceive less intrinsic job satisfaction then they will be more likely to think about leaving the EMS profession.

Other LEADS-based research has looked at antecedents or correlates of intent to leave the EMS profession without distinguishing between EMT-Basics versus EMT-Paramedics. Working with the 2005 LEADS data, Patterson et alReference Patterson, Moore, Sanddal, Wingrove and LaCroix 14 found that both EMT-Basics and Paramedics were least satisfied with opportunities for advancement and pay and benefits. Although only a small percentage (5.8%) intended to leave the EMS profession in the next 12 months, the odds for leaving were 3.7 times higher in the lowest yearly income category versus the highest income category. In addition, the odds for leaving were significantly higher among respondents who were dissatisfied with the EMS profession, pay and benefits, being able to help others, and their current assignment.

The 2007 LEADS survey included items about occupational identity issues and measured four types of occupational commitment: affective, normative, accumulated costs, and limited alternatives. Affective commitment refers to one’s emotional attachment to their occupation (I want to stay); normative commitment is a person’s sense of obligation to remain in their occupation (I should stay); continuance of commitment refers to the individual’s assessment of the costs associated with leaving one’s occupation (I have to stay); and limited alternatives (there are occupational alternatives for me).Reference Blau, Chapman, Pred and Lopez 15 Blau et alReference Blau, Chapman, Pred and Lopez 15 found that these four occupational commitment dimensions had a significant impact on intent to leave the EMS profession beyond controlled-for personal and job-related variables. The EMS respondents with low overall commitment were significantly more likely to intend to leave EMS than those with high overall commitment.

In a study looking at the impact of sleep issues and perceived health on intent to leave the EMS profession, BlauReference Blau 16 used a longitudinal design (2005, 2006, and 2007 LEADS respondents) and found that beyond background and work-related variables, perceived sleep-related impairment and lower health positively impacted intent to leave the EMS profession.

The Role of Stress in EMS Retention

Interviewees in the Patterson et alReference Patterson, Probst, Keith, Corwin and Powell 13 study noted that they not only dealt with work-related stresses such as being on call and dealing with the patients in traumatic events, but that work can interfere with one’s personal and family life. Cydulka et alReference Cydulka, Emerman, Shade and Kubincanek 17 found that 89% of EMT-Paramedics reported that their job was stressful and were psychologically worn out, or exhausted. Research indicates that the emotional labor (surface acting and deep acting) involved in being an EMS professional can play a role in such exhaustion.Reference Blau, Bentley and Eggerichs-Purcell 18 In addition, for both EMT-Basic and EMT-Paramedic samples, years of service were positively related to work exhaustion, while job satisfaction was negatively related. Work exhaustion has been linked to leaving one’s occupation in other allied health samples.

Two prior studies looked at LEADS exit data without differentiating between EMT-Basic and Paramedic samples.Reference Blau, Chapman, Gibson and Bentley 19 , Reference Blau and Chapman 20 In the first study, a breakdown of the respondents who left EMS showed that 52% had been in a fully compensated position, 18% had been in a partially compensated volunteer position, and 30% were in a noncompensated volunteer position.Reference Blau, Chapman, Gibson and Bentley 19 Across all three samples, a very high percentage of respondents indicated that they had not retired or stopped working after leaving their EMS position. A back injury (11%) was the highest indicated medical issue as a reason for leaving. Results showed that desire for better pay and benefits was a significantly more important reason for leaving EMS for the partially compensated leavers than for the fully compensated leavers.Reference Blau, Chapman, Gibson and Bentley 19 Perceived lack of advancement opportunity was a significantly more important reason for leaving for the partially compensated and volunteer groups than for the fully compensated group.

The second studyReference Blau and Chapman 20 focused only on the fully compensated sample which left EMS and looked at the relationship of the importance items to life satisfaction after leaving EMS, and likelihood of returning to EMS items. Looking at the means of the importance in leaving items, being stressed/burned-out and lack of job challenges were the most important factors in the decision to leave EMS, while surprisingly, desire for better pay and benefits was the least important. Looking at the correlations of the importance in leaving EMS factors with life satisfaction and the likelihood of returning to EMS items, career change desire was significantly positively related to life satisfaction after leaving EMS, and significantly negatively related to the likelihood of returning to EMS. Stress/burn-out was significantly positively related to life satisfaction after leaving EMS.

New analyses working with the LEADS data are reported below. These analyses further contribute to the knowledge of factors associated with satisfaction with EMS and intent to leave the job or profession.

Methods

The sampling methodology, weighting, and data collection procedures for the LEADS 10-year study are described by Levine in a dedicated section of this special issue. Each annual survey included one item measuring “EMS satisfaction with the profession” using a four-point response scale, where 1=very satisfied, 2=satisfied, 3=dissatisfied, and 4=very dissatisfied. Another yearly item measured “likelihood of leaving the EMS profession in the next 12 months” using a five-point response scale, where 1=definitely stay, 2=probably stay, 3=probably leave, 4=definitely leave, and 5=I have already left. In 2007 and 2008, an item measured likelihood of leaving one’s EMT job in the next 12 months, using the same five-point response scale as for leaving the EMS profession. Responses of individuals to these two items were compared in each year, using dependent t tests.

As part of LEADS, an exit survey was sent each year, over an 8-year time frame (1999-2007), to respondents in LEADS who had indicated that they had EMS certification but were not currently working in EMS. Exit survey respondents filled out this survey once.

Seventeen different items were specified, and respondents were asked “How important was each of the following in your decision to leave EMS?” Respondents used the following response scale, 1=very important, 2=moderately important, 3=slightly important, 4=not important, and 5=not applicable. The “not applicable” response was treated as missing data. These analyses exclude individuals who may have received some level of EMS certification but never worked in EMS.

Results

Satisfaction with EMS Profession and Likelihood of Leaving the EMS Profession

Table 1a compares mean level of satisfaction with EMS profession and Table 1b compares the mean likelihood of leaving EMS profession in the next 12 months for EMT-Basic versus Paramedic samples for each LEADS year. Yearly result comparisons between EMT-Basic and Paramedic samples collectively show a generally high mean level of satisfaction with the EMS profession for both samples. However, looking at the 95% confidence intervals (CI) around each satisfaction mean, the nonoverlap in CIs from 2002 to 2008 indicates that EMT-Basics were significantly more satisfied with the profession than EMT-Paramedics. Looking at intent to leave the EMS profession both EMT-Basics and Paramedics had a consistently low likelihood of leaving EMS in the next 12 months. Comparing the 95% CIs for each mean, only in 1999 was there a significant difference with Paramedics having a lower intent of leaving.

Table 1a Satisfactiona with EMS Profession: 1999-2008

Abbreviations: EMS, Emergency Medical Services; EMT, Emergency Medical Technician.

a1=very satisfied, 2=satisfied, 3=dissatisfied, 4=very dissatisfied.

Table 1b Likelihooda of Leaving EMS in the Next 12 Months: 1999-2008

Abbreviations: EMS, Emergency Medical Services; EMT, Emergency Medical Technician.

a1=definitely stay, 2=probably stay, 3=probably leave, 4=definitely leave, 5=I have already left.

Intent to Leave an EMT Job Versus the EMS Profession

For the 2007 and 2008 LEADS surveys, there was a one-item measure of “likelihood of leaving EMT job in the next 12 months.” The results comparing EMT-Basic versus EMT-Paramedic responses for likelihood of leaving job versus profession in 2007 and 2008 are shown in Table 2. In 2007 and 2008, for both EMT-Basics and Paramedics, the intent to leave job means were significantly higher than the means for intent to leave the EMS profession, supporting that they are distinct work role transitions.Reference Louis 4

Table 2 Likelihood of Leaving EMS Job in Next 12 Months Versus Likelihood of Leaving EMS Profession in the Next 12 Months for EMT-Basics and Paramedics: 2007 and 2008Footnote a

Abbreviations: EMS, Emergency Medical Services; EMT, Emergency Medical Technician.

a Response scale for both likelihood of leaving EMS job in next 12 Months and likelihood of leaving EMS in next 12 months: 1=definitely stay, 2=probably stay, 3=probably leave, 4=definitely leave, 5=have already left.

b P<.001 (two-tailed).

What do EMS Exit Data Tell Us?

Of the 1,036 exit surveys sent out over the eight years, 478 (46%) were returned. Of these 478 respondents, 234 (49%) indicated that they had never worked in EMS, while 244 (51%) had previously worked in EMS. A large percentage with EMT certification who received an exit survey but never worked in EMS may have never intended to join the EMS workforce. The EMT-Basics may work in jobs outside of EMS that either require or find EMS training beneficial, for example, ski patrol, search and rescue, summer camps, day care facilities, and police.

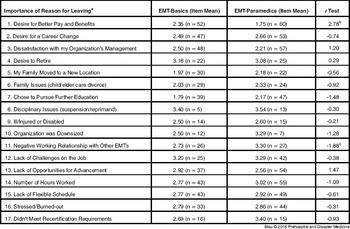

Comparing EMT-Basics versus EMT-Paramedics on reasons for leaving the EMS profession reveals only one significant difference as shown in Table 3. The desire for better pay and benefits was significantly more important (t=2.78, P<.01) for EMT-Paramedics (M=1.75) than EMT-Basics (M=2.35) as a reason for leaving the EMS profession. There was also a marginally significant difference (t=-1.88, P<.10) such that a negative working relationship with other EMT-Basics was a more important reason for leaving EMS for EMT-Basics (M=2.73) than EMT-Paramedics (M=3.30). The most important reason for leaving EMS for EMT-Basics was to pursue further education (M=1.79), while the most important reason for leaving EMS for EMT-Paramedics was better pay and benefits (M=1.75). The sample sizes for each group are generally quite small and reduce the power to detect a significant difference, even if there is a fairly large difference in item means, for example, lack of opportunities for advancement. In addition, there was no significant difference in means between EMT-Basics versus EMT-Paramedics on either satisfaction after leaving EMS or likelihood of returning to EMS.

Table 3 Importance of Reason for Leaving EMS for EMT-Basics Versus EMT-Paramedics

Abbreviations: EMS, Emergency Medical Services; EMT, Emergency Medical Technician; n, sample size.

a Response scale for importance of reason for leaving: 1=very important, 2=moderately important, 3=slightly important, 4=not important.

b P<.01 (two-tailed).c P<.10 (two-tailed).

Discussion

Importance of Understanding Why EMS Professionals Leave the Profession

As noted at the beginning of this paper, the BLS estimates that 62,000 EMS professionals will be needed in the next decade to fill new jobs and replace workers who leave the profession. 3 The good news is that the LEADS research shows a consistently high level of satisfaction with the EMS profession and despite somewhat higher job (within profession) turnover, a low intent to leave the EMS profession for both EMT-Basics and Paramedics. One likely reason that job turnover intent is higher than professional turnover intent is that EMS professionals may leave their current job to take another position in EMS if they move to another location. Continuing to monitor work attitudes such as job satisfaction and occupational commitment as well as intentions to leave a job and the EMS profession among current EMS professionals, as well as finding out why EMS professionals leave, are recommended for further study.

Stress is an issue affecting the retention of EMS professionals, and it includes both mental and physical components. Given the interpersonal demands on EMS professionals, emotional labor can be part of the stress in any traumatic situation, and surface acting is more detrimental to job satisfaction and increasing work exhaustion than deep acting.Reference Blau, Bentley and Eggerichs-Purcell 18 Making EMS professionals more aware of emotional labor including surface acting versus deep acting and the potential negative impact of surface acting via ongoing voluntary or state-required continuing education is recommended to enhance retention. At the same time, such continuing education could help EMS professionals to further develop their deep acting skills (via role plays). For example, one type of deep acting technique is cognitive change which involves reappraisal of a situation to lessen its emotional impact, for example, thinking about how a patient would feel.Reference Blau, Bentley and Eggerichs-Purcell 18

Decreased perceived physical health was related to higher intent to leave the EMS professionReference Chapman, Blau, Pred and Lopez 12 , Reference Blau 16 as well as work exhaustion.Reference Blau, Bentley and Eggerichs-Purcell 18 The EMS work is physically demanding. Studnek et alReference Studnek, Bentley, Crawford and Fernandez 21 found that 26% of their large EMS sample was obese and that three-quarters of the respondents did not meet the Center for Disease Control recommendations for physical activity. Mandatory ongoing physical fitness assessments of EMS professionals at their places of employment may be needed.

Extrinsic job satisfaction, especially a desire for better pay and benefits, is important for retention of EMS professionals.Reference Chapman, Blau, Pred and Lopez 12 - Reference Patterson, Moore, Sanddal, Wingrove and LaCroix 14 Limited exit data suggested this could be more so for EMT-Paramedics than EMT-Basics. While EMT-Paramedics generally earn higher wages than EMT-Basics, it may be that EMT-Paramedics’ salary expectations are higher given their increased investment in education.

In addition, lower intrinsic job satisfaction (eg, less challenge, or task variety) had a significant relationship with intent to leave the profession for EMT-Paramedics but not EMT-Basics.Reference Chapman, Blau, Pred and Lopez 12 Perhaps creating a “clinical ladder” for EMT-Paramedics, whereby as they increase their skill set they attain increasing rewards, may be beneficial to pilot. The exit data indicated that “desire to pursue further education” was the most important reason for EMT-Basics to leave the EMS profession. The EMT-Basic education may be used as a basis to launch into other further health professions such as nursing or allied health. These findings may be used to adjust analyses for the number of new EMS workers demanded for the future in order to meet population needs. If a predictable number of EMT-Basic education completers are known to enter non-EMS jobs or are expected to leave for other careers after a short EMS career, these data are valuable for EMS workforce planning.

Limited exit data found that EMT-Basics identified the interpersonal stress of negative working relationships with colleagues as a more important reason for leaving EMS than EMT-Paramedics. Professional peer-based camaraderie can be a powerful retention source for EMS professionals.Reference Patterson, Probst, Keith, Corwin and Powell 13 Key EMS stakeholders and administrators should consider facilitating mentor and/or peer support group programs to enhance the development of stronger camaraderie in different EMS-based organizations (eg, hospitals, and fire services).

Exit data noted that the desire for better pay and benefits was a significantly more important reason for leaving EMS for the partially compensated leavers than for fully compensated leavers, while perceived lack of advancement opportunity was a significantly more important reason for leaving for the partially compensated and volunteer groups.Reference Blau, Chapman, Gibson and Bentley 19 This suggests that it may be very important to give volunteer and partially compensated EMS professionals’ realistic expectations for becoming fully compensated and having advancement opportunities to enhance their retention. It may be useful to study the impact of giving volunteers other benefits, such as free continuing education, on their EMS retention.

Future Research Ideas to Consider

A number of future research ideas are worth considering based on initial LEADS-related study findings and other relevant research. Given the interpersonal stress of being an EMS professional, the role of emotional labor (surface acting vs. deep acting) should continue to be explored, including its impact on EMS professionals’ withdrawal intent. Prior qualitative research noted that work interfering with family was an important stress faced by EMS professionals.Reference Patterson, Probst, Keith, Corwin and Powell 13 The impact of this stress on EMS profession withdrawal intent should be investigated. Limited exit data found that negative co-worker relationships had a marginally significant greater impact on leaving EMS for EMT-Basics than EMT-Paramedics. In their firefighter sample, Tuckey and HaywardReference Tuckey and Hayward 22 found that high camaraderie weakened the relationships between emotional demands burn-out and psychological distress. Perceived quality of co-worker relationships should be assessed in future research. Work exhaustion, particularly with more tenured EMS professionals, may have a stronger impact on professional retention versus newer EMS professionals. This supports distinguishing and tracking newer versus more experienced EMS cohorts.

Prior research as well as exit data have identified both extrinsic satisfaction issues (eg, pay, advancement, and benefits) as well as intrinsic satisfaction issues (eg, task variety, autonomy, and challenging job) as important to EMS professional retention.Reference Chapman, Blau, Pred and Lopez 12 , Reference Patterson, Probst, Keith, Corwin and Powell 13 However, these extrinsic and intrinsic satisfaction scales were composed of aggregated study-specific items. It would be useful to consider prevalidated short extrinsic and intrinsic satisfaction-related scalesReference Spector 23 in future research. Survey-space permitting, the four-dimensional occupational commitment measure could continue to be used since initial researchReference Blau, Chapman, Pred and Lopez 15 indicated that it was able to account for significant additional intent to leave EMS profession variance beyond job satisfaction, health, and other controlled-for relevant variables.

Limitations

A difficult issue with any type of survey research is to have a longitudinal study with repeat respondents tracked over time. The LEADS project suffered from this issue, as there were approximately 1,500-1,900 complete data respondents (all levels of EMS certification) in any given year, but only 51 complete data across all 10 years. A 3-year longitudinal LEADS study had a complete data sample of only 288 repeat respondents, which was only 4% of the total respondent database.Reference Blau 16 Thus, each of the ten LEADS surveys represents a cross-sectional “snapshot” of demographic, work attitude, perceptual, and behavioral intention variables. In any type of cross-sectional research it is difficult to assess causality, for example, that satisfaction causes intent to leave. Having a bigger cohort of repeat respondents in future research efforts would be very helpful. Perhaps prestudy identification of such respondents and possible cost-effective incentives (eg, reduced meeting registration fee or professional magazine subscription) could be used to help create such a cohort. Being able to compare a “new to EMS” versus “experienced EMS” longitudinal cohort could help to identify early career versus later career retention issues.

Another limitation of this study is the fact that the distinction between intent to leave one’s job versus the EMS profession was made only during the last two years of the LEADS study. Finally, collecting actual EMS job turnover or occupational turnover data can be challenging for several reasons, including the need for careful records, but even having only a smaller subset of such turnover data would allow for stronger data analyses than a proxy-only intent to leave measure.Reference Patterson, Jones and Hubble 5

Conclusion

Given the expected increased demand for EMS professionals in the next decade, continued study of EMS workforce retention is needed. Summarizing prior LEADS-based research and new LEADS-based findings in this paper has given insight into current issues affecting such retention as well as suggestions for future research to improve EMS workforce retention. Continued differentiation of EMT-Basic versus EMT-Paramedic samples is recommended.