Introduction

Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2019; p. 133) defined personal practice (PP) ‘as formal psychological interventions and techniques that therapists engage with self-experientially over an extended period of time (weeks, months or years) as individuals or groups, with a reflective focus on their personal and/or professional development’. PP includes various theoretical foundations (e.g. psychodynamic), terms, concepts and methods (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Laireiter and Willutzki, Reference Laireiter and Willutzki2003). It is a compulsory training element for many accreditation bodies (e.g. the European Certificate of Psychotherapy; ECP Official Document, 2017). The general aim of PP in therapists’ training is the systematic promotion of therapeutic competences, as well as of personal and interpersonal skills (Laireiter, Reference Laireiter, Linden and Hautzinger2015). There is, however, no consensus on the operationalizable subgoals of PP (Laireiter and Willutzki, Reference Laireiter and Willutzki2003).

The generic PP model describes the associations between PP and therapeutic effectiveness (Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018; Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019). It is derived from the Declarative-Procedural-Reflective (DPR) model (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006) and from empirical research on different forms of PP [personal therapy, meditation-based programs, self-practice and self-reflection (SP/SR) programs]. The so-called ‘personal self’ and the ‘therapist self’ form the framework of the model. The five main effects, which may result from engaging with PP (personal development and well-being; self-awareness; interpersonal beliefs, attitudes and skills; reflective skills; conceptual and technical skills) lie within the two overlapping self-parts. Furthermore, four motivations to engage in PP are associated with these outcomes: personal problems, personal growth, self-care, and therapist skill development. To promote therapeutic skillfulness, the reflection process is central, and includes ‘personal self-reflection’, ‘therapeutic self-reflection’ (Wigg et al., Reference Wigg, Cushway and Neal2011) as well as the reflective bridge, which is a transition between both self-reflections.

Regarding the empirical research on different PP forms, studies suggest various positive effects on personal and professional development, like interpersonal skills (e.g. empathy) and self-awareness (e.g. Edwards, Reference Edwards2018; Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014; Moe and Thimm, Reference Moe and Thimm2021; McMahon and Rodillas, Reference McMahon and Rodillas2020; Orlinsky et al., Reference Orlinsky, Schofield, Schroder and Kazantzis2011; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Yap, Bunch, Haarhoff, Perry and Bennett-Levy2021; Strauß and Taeger, Reference Strauß and Taeger2021). Furthermore, a high convergence between the reported PP effects and characteristics of effective therapists, as well as its central role in promoting personal and interpersonal competences is assumed (e.g. Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Moe and Thimm, Reference Moe and Thimm2021). Nonetheless, negative effects have also been reported, such as distress and destabilization (e.g. Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Irfan, Barnett, Castledine and Enescu2018; Laireiter, Reference Laireiter, Linden and Hautzinger2015) and so far, no study has convincingly related the effects of PP on client outcomes (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019). However, it is important to recognize the methodological weaknesses (e.g. no control group) of most of the studies (e.g. Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Moe and Thimm, Reference Moe and Thimm2021).

Factors that may influence the experience of benefit and engagement with PP include course structure and requirements, feelings of safety, expectations of benefits, group processes, and personally accessible resources, like trainee perceptions of individual time (e.g. Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Haarhoff et al., Reference Haarhoff, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2015). Additionally, different techniques (e.g. method of action in PP-like role-play) and topics (e.g. the categories of PP that are discussed such as therapeutic relationship) can be expected to have different benefits. For example, in a survey study, experienced psychotherapists perceived different training methods (e.g. experiential work, reflective practice) to aid different types of skills (e.g. promotion of reflective and interpersonal skills; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009), while in an another study students evaluated interactive teaching methods (e.g. demonstrating/modelling) as more effective than didactic alternatives (e.g. reading lists) in supporting their learning (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Pachana and Sofronoff2011). Furthermore, different benefits deriving from PP depending on the focus of the content (Schön et al., Reference Schön, Frank and Vaitl1998), the need for PP exercises to be grounded in appropriate content (e.g. matching with the training curriculum; Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019), and the usefulness of the engagement with both the ‘personal self’ and ‘therapeutic self’ (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014), were discussed. To date, there is still only limited knowledge about effective factors in creating helpful PP (e.g. Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019), which is important for improving training standards.

In Germany, PP is a compulsory component of state-approved psychotherapy training (PsychThG, 1999) with 120 hours in an individual or group format (§5, PsychTh-APrV). Since a law reform in 2020, self-reflection is also a compulsory part of the newly established psychotherapy studies (§11, PsychThApprO) and PP will probably again be part of the psychotherapeutic training (BPtK, 2022). According to these regulations, PP is described as ‘the reflection on or modification of personal requirements for therapeutic experience and action […]’ (translated by the first author; §5, PsychTh-APrV). This is in line with the above-mentioned definition of PP by Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2019), which describes reflection as the central element of PP. Additionally, the focus on the ‘personal self’ is apparent, and an important differentiating factor when comparing PP with other training strategies (e.g. clinical supervision, deliberate practice), although the latter can also include a focus on the ‘personal self’ or may have a PP component, respectively (Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018; Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019). Modifying personal requirements are mentioned in these regulations, but there are no further specifications about the implementation of PP, especially on which settings or methods to use (e.g. personal therapy, experiential or personal development groups, pre-defined SP/SR programs). Although there are legal pre-requisites (licensure, at least 5 years of clinical practice, at least 3 years of lecturing experience, personal suitability) for PP leaders, a mandatory training program is not required (PsychTh-APrV). This is of particular interest, given that practising PP is, as mentioned above, diverse, for example regarding the frequency of topics discussed and techniques applied. Hence, the aim of this article is to learn more about the discussed topics and applied techniques of PP in German psychotherapeutic training and their perceived effects.

Based on previous supervision research (e.g. Weck et al., Reference Weck, Kaufmann and Witthöft2017) and on the results of a qualitative study (Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Weck, Witthöft, Maiwald, Foral and Kühne2021), the aim of the present study was an exploratory, systematic examination of the characteristics (e.g. topics, techniques) and effects (e.g. positive, negative) of PP applied during state-approved psychotherapy training in Germany. The research questions were: (1) which PP topics are discussed, how frequently, and which are perceived as useful?; (2) which PP techniques are applied, how frequently, and which are perceived as useful?; (3) what positive and negative effects are reported and described as helpful/impairing?; (4) are there any differences in the PP evaluations between therapeutic orientations [i.e. cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT); psychodynamic therapy (PT)]?; and (5) what suggestions are helpful for PP from a participant’s perspective?

Method

Recruitment, inclusion criteria and sample

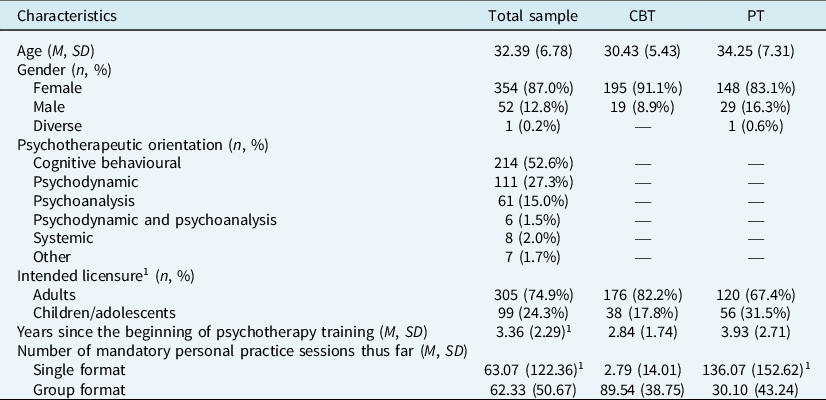

Participants were recruited between January and February 2020, at postgraduate psychotherapy training institutions throughout Germany. We contacted 210 training institutes by email, and asked them if they would be willing to distribute a link to a larger online survey of which the current study is part of among their trainees, with the result that N = 757 individuals started and N = 468 completed the survey. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) current participation in psychotherapy training (n = 1 excluded), (2) at least one previous mandatory PP session (n = 56 excluded), (3) completion of the relevant questionnaires (n = 3 excluded) and (4) informed consent (n = 1 excluded). Characteristics of the final sample (N = 407) are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants for the total sample (N = 407) and separated for CBT (n CBT = 214) and PT (n PT = 178)

1 Missing information.

CBT, cognitive behavioural orientation; PT, psychodynamic/psychoanalytic orientation.

Measures

We included a brief sociodemographic questionnaire in order to collect data such as age, gender, psychotherapeutic orientation, and variables relating to psychotherapeutic and PP experience.

General satisfaction with PP

We asked participants about their general satisfaction with PP (1, not at all; 2, some; 3, medium; 4, quite; and 5, very), as well as about the effects of PP (1, negative; 2, rather negative; 3, no effects; 4, rather positive; 5, positive) on their personal development and on their therapeutic competence. Questions were asked separately for PP delivered in an individual as opposed to a group format. Additionally, we asked the participants to give their individual benefit–cost evaluation of PP (1, negative; 2, rather negative; 3, balanced; 4, rather positive; 5, positive).

Topics, techniques, effects and open-answer sections

The questions regarding the topics, techniques and effects of PP were based on the category system of a previous qualitative study (Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Weck, Witthöft, Maiwald, Foral and Kühne2021) and on empirical literature (e.g. Laireiter and Willutzki, Reference Laireiter and Willutzki2003; Laireiter, Reference Laireiter, Linden and Hautzinger2015). The questionnaire assessed the frequency, perceived personal usefulness (e.g. refers to private situations and requirements) and perceived usefulness for therapeutic activity (e.g. refers to professional situations or requirements in therapeutic work) of 14 topics (e.g. therapeutic relationship) and 16 techniques (e.g. role-play) in relation to PP. For 15 positive effects (e.g. interpersonal competence), and three negative effects (e.g. destabilization of mood) the occurrence, the perceived personal usefulness/impairment and the perceived usefulness/impairment for therapeutic activity in relation to PP were examined. Topics and negative effects each included an item based on group experiences. Four-point scales were used for frequency (1, never; 2, rarely; 3, sometimes; and 4, often) and for occurrence/usefulness/impairment (1, not at all; 2, some; 3, quite; and 4, very). In an open-answer section, participants had the opportunity to report other topics, techniques, effects, improvements or problems they had experienced with PP.

The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the frequencies/occurrences (without the group-PP based items) were as follows: .86 for topics, .83 for techniques and .94 for positive effects (excluding negative effects, due to the small number of items).

Data analysis

For data analysis, IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23) and MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019) were used. The significance level was set to α = .05. Items which required specific PP experiences (e.g. PP in a group format) were only computed if participants indicated having had the relevant experience. For the calculation of group differences, and due to the small sample size, we excluded systemic therapy (n = 8), as well as other forms of therapy (n = 7), and pooled participants from psychoanalytical and/or psychodynamic orientations into one group (n PT = 178). We then contrasted PT with CBT (n CBT = 214) participants. We analysed group differences in terms of categorical variables (e.g. gender) computing Phi coefficients (ϕ), while we examined dimensional variables (e.g. age) using t-tests. Group differences regarding the frequency/occurrence and perceived usefulness/impairment of topics, techniques and effects were examined using multiple t-tests. Thus, we applied the Bonferroni-correction (0.05/number of tests per examined category). For unequal population variances, we computed Welch’s t-tests. Cohen’s d was used as the effect size (d = 0.2 small; d = 0.5 medium; d = 0.8 large; Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). We also analysed differences concerning the frequency/occurrence (without the group-based items) in a single statistical procedure using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). We defined the items measuring topics, techniques, positive and negative effects as the dependent variables. The psychotherapeutic orientation (CBT and PT) was the independent variable. The MANOVA was not computed for the perceived usefulness/impairment, due to a different number of participants for each item (required specific PP experience; e.g. discussion of the specific topic). The answers to the open questions were evaluated based on qualitative content analysis techniques (Mayring, Reference Mayring2015). Text passages were paraphrased, generalized and reduced. Categories were formed deductively (assignment to research questions) and inductively (plausibility check) as well.

Results

Characteristics of participants and of PP

PT trainees (Table 1) were on average 3.82 years older (t 320.70 = –5.78; p<.001; d = –0.60), were more often male (Φ = –.114; p = .02; excluding diverse n = 1), were 1.09 years longer in psychotherapy training (t 290.64 = –4.62; p<.001; d = –0.49), and had received 133.28 more hours of PP in a single format (t 178.45 = –11.58; p<.001; d = –1.29) than CBT trainees, while CBT trainees had received on average 59.44 more hours PP in a group format (t 359.25 = 14.20; p<.001; d = 1.46). In total, PT trainees had received significantly more hours of PP than CBT trainees (t 200.23 = –6.66; p<.001; d = –0.73).

General satisfaction with PP

In the group format, 61% of the trainees indicated being ‘quite’ or ‘very’ satisfied with PP (n = 287; M = 3.74; SD = 1.12), which applied to 87% of the participants regarding single format PP (n = 199; M = 4.41; SD = 0.84). Additionally, when evaluating the effects of PP for personal competence, on the 5-point Likert scale, the ‘rather positive’ or ‘positive’ responses were endorsed by 78% (n = 120; M = 4.13; SD = 0.88) of trainees in the group format and 95% (n = 199; M = 4.56; SD = 0.66) in the individual format, while 79% (n = 121; M = 4.17; SD = 0.83) of group format and 90% (n = 198; M = 4.44; SD = 0.72) of individual format trainees endorsed the same responses for therapeutic competences. Only 1% of the trainees indicated (rather) negative impacts for personal and 4% for therapeutic competences. However, 16% of the trainees evaluated the benefit-cost analysis (n = 407; M = 3.86; SD = 1.17) as (rather) negative, while 66% indicated a (rather) positive outcome.

Regarding group differences, PT trainees were more satisfied with PP in a group format (t 275 = –2.31; p = .02; d = –0.32; CBT: n = 210, M = 3.66, SD = 1.08; PT: n = 67, M = 4.01, SD = 1.19), evaluated the effects of PP in a single format for their therapeutic competences as more positive (t 189 = –3.00; p = .003; d = –0.71; CBT: n = 20, M = 4.00, SD = 0.86; PT: n = 171, M = 4.50, SD = 0.68) and estimated the benefits versus the costs of PP as more positive (t 389.34 = –4.77; p<.001; d = –0.48; CBT: n = 214, M = 3.61, SD = 1.20; PT: n = 178, M = 4.15, SD = 1.04) than CBT trainees. The groups did not differ regarding other items concerning the general satisfaction with PP (p>.05).

Frequency and usefulness of specific topics

Figure 1 presents the frequency and perceived usefulness of specific topics. ‘Individual topics’ followed by ‘Biography work’ were the most frequently discussed and perceived as most personally useful topics. For therapeutic activity, elaborating on the ‘Therapeutic relationship’ and on the ‘Therapeutic self-concept’ were perceived as most useful.

Figure 1. Specific topics in personal practice (PP) for the total sample (N = 407): mean scores and error bars (represent ±1.96 standard error). Scale range: frequency (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often), usefulness (1 = not at all, 2 = some, 3 = quite, 4 = very). *Only participants who received personal practice in a group format (n = 291).

The frequency of topics worked on and their perceived usefulness differed for the majority of the items significantly between CBT and PT trainees (Supplementary material, Table A). Each topic, with the exception of ‘Satisfaction with PP’, was used more frequently by the PT trainees. PT trainees also perceived all items with the exceptions of ‘PP goals and agreements’ and ‘Group cohesion/dynamics’ as more personally useful, and all items, with the exception of ‘PP goals and agreements’ as more useful for therapeutic activity (all other comparisons p<0.05/14). In the case of ‘Individual topics’ (frequency, personal usefulness, usefulness for therapeutic activity), ‘Self-concept’ (frequency) and ‘Therapeutic relationship’ (frequency, personal usefulness) large effect sizes were found. The MANOVA confirmed the above-mentioned significant differences between CBT (M = 2.52; SD = 0.55) and PT (M = 3.01; SD = 0.48) trainees for the frequency of topics (V = .47; F 13,378 = 25.54; p < .001).

Frequency and usefulness of specific techniques

Figure 2 presents the frequency and perceived usefulness of the examined techniques. The techniques ‘Instructions for self-reflection’ and ‘Self-experience of therapeutic methods’ were used most frequently, while ‘Instructions for self-reflection’ was perceived as most personally useful, and ‘Self-experience’ was evaluated as most useful for therapeutic activity. Some techniques such as ‘Role-play’, ‘Body-oriented exercises’, ‘Homework’ and ‘Audio/videotapes’ were applied seldom or never.

Figure 2. Specific techniques in personal practice (PP) for the total sample (N = 407): mean scores and error bars (represent ±1.96 standard error). Scale range: frequency (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often), usefulness (1 = not at all, 2 = some, 3 = quite, 4 = very).

Significant differences between CBT and PT trainees regarding the frequency were found for half of the examined techniques including ‘General PP goals and content’, ‘Role-play’, ‘Feedback’, ‘Imagination exercises’, ‘Techniques for mindfulness’, ‘Body oriented exercises’, ‘Case discussion’ and ‘Homework’ (p< .05/16; Supplementary material, Table A). Apart from ‘Case discussion’, all these techniques were used more frequently in the CBT group. Furthermore, differences were found regarding the perceived usefulness. Each technique, except for ‘General PP goals and content’, ‘Role-play’, ‘Feedback’, ‘Homework’ and the use of ‘Audio/videotapes’, was perceived as personally more useful by PT than CBT trainees. Regarding the perceived usefulness for therapeutic activity, no differences between PT and CBT trainees were found for these techniques, as well as for ‘Own goals and content’, ‘Self-experience’ and ‘Imagination exercises’. All other techniques were perceived as more useful for therapeutic activity by PT than CBT trainees (p<0.05/16). Large effect sizes were found for ‘Role-play’ (frequency), ‘Imagination exercises’ (frequency), ‘Techniques for mindfulness’ (usefulness for therapeutic activity), ‘Body-oriented exercises’ (personal usefulness, usefulness for therapeutic activity) and ‘Homework’ (frequency). The MANOVA confirmed the above-mentioned significant differences between CBT (M = 2.26; SD = 0.51) and PT (M = 2.00; SD = 0.51) trainees for the frequency of techniques (V = .56; F 16,375 = 29.37; p<.001).

Positive and negative effects of PP

Figure 3 presents the frequency and perceived usefulness of different positive and negative effects. Positive effects reported with the strongest occurrence were establishing ‘Knowledge of individual patterns’ followed by the advancement of ‘(Self-)reflective ability’ and the promotion of ‘Interpersonal competences’. The advancement of ‘(Self-)reflective ability’ was evaluated as most personally useful, while the promotion of ‘Interpersonal competences’ was perceived as most useful for therapeutic activity.

Figure 3. Positive and negative effects in personal practice for the total sample (N = 407): mean scores and error bars (represent ±1.96 standard error). Scale range: Occurrence/usefulness/impairment (1 = not at all, 2 = some, 3 = quite, 4 = very). *Only participants who received personal practice in a group format (n = 291).

All examined positive effects were reported with a stronger occurrence and perceived as more helpful by the PT group (all p<.05/15; Supplementary material, Table A). Strong effects were found regarding the promotion of ‘Process competences’, of ‘Interpersonal competences’ and of the ‘Identification with one’s own psychotherapeutic approach’ (Supplementary material, Table A). The above-mentioned significant differences between CBT (M = 2.52; SD = 0.64) and PT (M = 3.14; SD = 0.61) trainees for the occurrence of positive effects (V = .47; F 15,376 = 21.94; p<.001) were confirmed by the MANOVA.

Regarding negative effects, ‘Energy consumption and exhaustion’ was reported with the strongest occurrence, with CBT trainees indicating it significantly stronger than PT trainees (Supplementary material, Table A). While no significant differences emerged regarding negative effects for the perceived personal impairment, ‘Destabilization of mood’ and ‘Negative group experience’ were indicated as more debilitating for therapeutic activity by PT than CBT trainees. The MANOVA confirmed the above-mentioned significant differences between CBT (M = 2.37; SD = 0.74) and PT (M = 2.24; SD = 0.75) trainees for the occurrence of negative effects (V = .04; F 2,389 = 8.15; p<.001).

Categories derived from the open answers

Most of the participants mentioned further helpful characteristics of PP (n = 255, Table 2; Supplementary material, Table B). Most frequently, trainees indicated characteristics of the organization (n = 234; e.g. temporal structure). Other categories were PP leader characteristics (n = 58; e.g. implementation skills), a sustainable relationship with the PP leader (n = 16) and with the PP group (n = 15). Characteristics of the participants themselves were reported least often (n = 24; e.g. willingness to learn/self-openness).

Table 2. Categories derived from the open answers

n, number of participants who provided information; PP, personal practice.

The second category was on the effects of PP (n = 173). The most frequently reported additional negative effect was the costs of PP (n = 116), which clearly differed from the quantitative answers reported above. Specific positive effects were mentioned less often (n = 57; e.g. promotion of emotional competences). Furthermore, participants named specific topics (n = 39; e.g. dealing with crises and conflict situations) and techniques (n = 33; e.g. biography techniques) as helpful.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate PP topics, techniques, effects and characteristics, in order to supplement the current empirical knowledge on (helpful) PP. Experiential and reflective techniques were among those reported most frequently and as most helpful. The promotion of interpersonal, personal and reflective competences was among the predominant positive effects of PP. Nonetheless, negative effects, such as exhaustion, were also reported. Between therapeutic orientations differences emerged in PP practice.

More focus on evidence-based PP topics and techniques is needed

Although topics rated as most personally helpful were among those discussed most often (e.g. ‘Biography-work’), topics perceived as most helpful for therapeutic activity were less commonly a part of PP (e.g. ‘Therapeutic relationship’). In previous research, a combination of professional and personal topics (Schön, Reference Schön2001), as well as engagement with the ‘personal self’ and ‘therapist self’ (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014) were reported as helpful. Following a competence-based framework (Rief, Reference Rief2021), the selection of PP topics should focus on empirically derived mechanisms and processes (e.g. characteristics of effective therapists, such as interpersonal skills; e.g. Heinonen and Nissen-Lie, Reference Heinonen and Nissen-Lie2020) instead of a traditionally based selection.

In this study, self-reflection and self-experience were among the most frequently applied and rated as helpful techniques during psychotherapy training. Accordingly, these techniques have been associated with the promotion of reflective and interpersonal skills alike (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009). Nonetheless, many participants also indicated that these techniques were used only rarely or even never. Feedback was another of the techniques used most frequently and evaluated as helpful. Especially if based on direct strategies (e.g. observation-, video-based), feedback can play an important role in fostering therapeutic competences (e.g. Falender and Shafranske, Reference Falender and Shafranske2014). Additionally, role-play was applied less frequently, although it has been identified as an effective learning strategy for interpersonal and technical knowledge and skills (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009). Likewise, structuring techniques (such as setting PP goals) were also applied less frequently, even though defining course structure and requirements (e.g. Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2019) and a transparent rationale (e.g. Edwards, Reference Edwards2018; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Irfan, Barnett, Castledine and Enescu2018) are highly recommended. These results indicate that, as with respect to the topics, it might be useful to include more evidence-based techniques in PP curricula, for which the current implementation of the law reform on psychotherapy training in Germany offers an important opportunity.

Positive but also more negative PP consequences than expected

Our results indicate that organizational characteristics (e.g. temporal structure), skills of the PP leader (e.g. interpersonal), sustainable relationship with the leader and group and trainee willingness to learn are helpful PP characteristics. These results are in line with current recommendations, such as the implementation of a transparent PP concept and ethical protocols, as well as the importance of trainee level of engagement (e.g. McMahon and Rodillas, Reference McMahon and Rodillas2020; Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014). Additionally, providing specific trainings for PP leaders might be beneficial.

The majority of participants perceived positive effects of PP in promoting personal, interpersonal and therapeutic competences, which is in line with previous research (e.g. Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018; Moe and Thimm, Reference Moe and Thimm2021; Strauß and Taeger, Reference Strauß and Taeger2021; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Yap, Bunch, Haarhoff, Perry and Bennett-Levy2021). However, our results also indicate negative effects of PP, particularly ‘Energy consumption and exhaustion’ and ‘Costs’. Of particular concern, 16% of the trainees evaluated the benefit-cost analysis as (rather) negative, and a few participants described disturbing negative experiences in the open-answer section, like negative experiences with the leader (n = 13; e.g. ‘repeatedly, the leader became verbally aggressive’). Negative effects such as destabilization and distress, as well as difficult experiences with the leader (e.g. lacking appropriate skills) are consistent with the previous literature (Edwards, Reference Edwards2018; Laireiter, Reference Laireiter, Linden and Hautzinger2015; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Irfan, Barnett, Castledine and Enescu2018). Furthermore, there are also indications that mandatory PP in training contexts can have negative effects (e.g. destabilization) on trainees, especially if there is no clear rationale (Edwards, Reference Edwards2018; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Irfan, Barnett, Castledine and Enescu2018). Overall, this study indicates that a discussion of ethical issues, for example the availability of emotional support in cases of prolonged distress and the utilization of mandatory PP as a pedagogical opposed to a curative device, is necessary (McMahon and Rodillas, Reference McMahon and Rodillas2020; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Irfan, Barnett, Castledine and Enescu2018). Additionally, better definitions, and consensus on the competences to be promoted in PP and their operationalizations (e.g. Edwards, Reference Edwards2018; Moe and Thimm, Reference Moe and Thimm2021) might be beneficial.

Are psychodynamic trainees more satisfied with PP?

Almost all examined topics and positive PP effects were reported more frequently/with a stronger occurrence and were perceived as more helpful by PT than by CBT trainees. Only one small difference between both groups was found regarding the occurrence of negative PP effects. Although various PP techniques were used more frequently by CBT trainees, PT trainees perceived various techniques as more helpful.

For the interpretation of our results, it should be taken into account that CBT trainees have almost exclusively completed PP in a group format, while PT trainees have predominantly carried out PP in an individual format and completed more PP hours in total. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the results are due to different therapeutic orientations or to different PP formats and durations. Furthermore, at the time of investigation, PT trainees were older and had received more hours of psychotherapy training. Additionally, other characteristics, for example, trainee’s own experience as a psychotherapy patient, could have an effect on PP (e.g. Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Bennett-Levy, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2021).

Furthermore, the items we selected for our questionnaire might have had an influence on the reported results. For instance, trainees reported no differences in the frequency of self-experience and the reflection techniques, key techniques according to the definition of PP (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019), as well as modification of personal and therapeutic patterns, which are mentioned in the German regulations (§5, PsychTh-APrV). However, these techniques were perceived as more useful by the PT trainees.

Increased subjective significance of PP in PT compared with CBT was also found in earlier research, which has been discussed by pointing out that PP was initially not part of CBT training (Strauß and Taeger, Reference Strauß and Taeger2021). Additionally, the way PP is implemented should be considered more carefully. PP is often important for different reasons, purposes and goals, with respect to different theoretical orientations (Orlinsky et al., Reference Orlinsky, Geller, Norcross, Geller, Norcross and Orlinsky2005; Lazarus, Reference Lazarus1971) and it is assumed that there may be (dis-)advantages of different PP forms, depending on the context (Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Bennett-Levy, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2021). Interestingly, a recent study found more positive perceptions of CBT trainees using SP/SR for their personal and professional development, than of counselling trainees who used personal therapy, suggesting that for CBT SP/SR, a more controlled and structured procedure (e.g. with a clear main purpose for the promotion of therapeutic skills and a formalized reflection process; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014) might be a more appropriate choice – especially in mandatory formats (Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Bennett-Levy, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2021). Consequently, it might be that the factors (e.g. structure) that were included less in the examined PPs, might be the factors which help CBT trainees to experience PP more positively. The issue of specificity of the PP approach to therapy modality thus requires future research.

In summary, various factors might have contributed to the differences between CBT and PT trainees, enabling different routes for subsequent research.

Limitations

Although it is relevant to include the individual perspectives of trainees, their self-reports might be confounded by memory bias or cognitive dissonance reduction in the context of training costs (to date, in Germany, trainees pay several thousand Euros for psychotherapy training). Group differences were investigated exploratorily, and should thus be interpreted with caution. In addition, the PP modality used (e.g. personal therapy, unstructured reflection, SP/SR) could have contributed to differences. In this context, the question also remains as to whether the trainees really underwent PP or something that was merely referred to as PP.

Second, no definitions of topics, techniques and effects were provided to the trainees, which might have led to variations in their responses, depending on how they perceived the items. Additionally, due to the lack of a validated instrument, the questionnaire was developed specifically for the present study. Therefore, the examined items are a selection, which also implies that another sequence of items would be possible. In future studies, factor analytical examinations and test–retest reliability could be considered. Due to multiple tests, we have marked results in Table A of the Supplementary material, which were no longer significant after using the Bonferroni correction.

Third, due to the study design, we are not able to draw conclusions on causality. However, from our study, we conclude that in future studies, randomized controlled (e.g. comparing different PP techniques) and longitudinal designs should be used, additional sources of information (e.g. direct observation, validated questionnaires) should be included, and a multi-perspective approach considered.

Conclusions

The literature suggests that PP might play an important role in the promotion of personal and interpersonal skills and may supplement conventional training strategies (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019). Key to PP are self-reflection and self-experience (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019), which became apparent in our trainees’ positive responses as well. In particular, the open question responses reveal several negative and unwanted effects. Besides conducting more research on PP and its components, so as to further improve training, we encourage adhering to ethical considerations and transparent standards when implementing PP.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465822000406

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (D.H.) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Brian Bloch (University of Münster) for his English language editing of the manuscript. Furthermore, we would like to thank all participants for their support.

Author contributions

Daniela Hahn: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (equal), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal); Florian Weck: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Michael Witthöft: Methodology (supporting), Resources (lead), Supervision (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal); Franziska Kühne: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Psychology at the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz (application 2018-JGU-psychEK-028-X1). Participants provided written informed consent.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.