When legislators decide to switch their party loyalties, they do so, as Muller and Strom (Reference Muller and Strom1999) have shown, to increase their support levels, accrue additional office benefits, or shape some desired policy outcome.Footnote 1 These individual factors are clearly important, but we also know that there are other factors that legislators must take into account when they consider abandoning their current political parties for other organizations. These factors involve the risks associated with changing party loyalties, which legislators must weigh against the benefits they hope to gain by switching.

Exactly how much risk there is in a party exit decision will naturally be a function of a legislator's level of support and whether or not an incumbent politician is confident that extant support will carry over to a new political party. Electoral risk will also be molded by the characteristics of the alternative parties that can serve as new homes for exiting legislators. Indeed, whether a legislator's alternative is a viable, electorally seasoned organization or an untested start-up party will certainly involve different levels of electoral risk. Finally, as O'Brien and Shomer (Reference O'Brien and Shomer2013) and Klein (Reference Klein2018) have noted, some electoral rules, like presidential and other personalistic institutions, are more supportive of legislators contemplating a move to a new organization and, thus, reveal higher levels of party switching.

The individual factors that motivate legislators to consider switching parties are associated with the benefits they hope to obtain, and, thus, exiting legislators weigh these benefits against those factors that militate against a switch of parties being successful. As stated above, one of these factors is the electoral environment, which refers primarily to the actual alternative choices available to legislators and will be associated with different levels of electoral risk. Heller and Mershon (Reference Heller and Mershon2005) note that decisions to switch parties can involve a simple process of out-switch and in-switch, and they can also involve cases of fusion of one or more parties or cases of party fission, where new organizations are created out of the dissolution of an existing political party or political parties. They can also involve legislators joining a new, start-up organization that is electorally untested, rendering that exit decision generally more risky compared to joining a well-established political party.

Risk is also a function of the incentives that legislators face due to their respective countries' electoral rules. Again, while scholars have noted that party switching occurs more often in personalistic electoral systems, they have also concluded that the impact of electoral institutions on party switching is both limited and indirect. We understand why scholars have reached this conclusion but nonetheless ask whether we would get a different, more nuanced, direct institutional impact if we considered the manner in which institutional incentives and available party alternatives taken together were weighed against legislators' desires for increased electoral support, specific policy outcomes, or higher-level office benefits.

Our purpose in this paper is to investigate the interrelationships that exist between individual motivations and aggregate factors by focusing specifically on the sources of electoral risk that party incumbents necessarily weigh against the potential benefits associated with a move to another party organization. To accomplish this, we examine the exit decisions of 88 incumbents of the declining Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) in the 2017 snap election. Examining DPJ incumbent exit decisions in this contest will allow us to determine how individual motivating factors were molded by such aggregate factors as what party alternatives were available to DPJ incumbents and the fact that Japan's unique election system reduced some electoral risk for some but not all DPJ incumbents who faced the decision of having to leave the disbanded DPJ. We begin this effort with a discussion of the patterns of party switching that we have witnessed in postwar Japan.

1. Explaining party switching in postwar Japan

Party switching is nothing new in Japanese politics because it has occurred on both small and larger scales throughout the postwar period.Footnote 2 Examples of smaller-scale switching include the 1960 exit of right-leaning members of the former Japan Socialist Party (JSP) to form the Democratic Socialist PartyFootnote 3 and, in 1977, when another group of right-leaning JSP members left the party to form the Social Democratic League. Examples also include a number of anti-corruption Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) members exiting this predominant party to form the New Liberal Club in 1976.

There are also cases of more significant party switching and new party formation such as the changes that occurred surrounding the 1993 and 1996 lower-house elections. The former contest witnessed two new parties formed by exiting members of the LDP, specifically, the Japan Renewal Party, formed by 44 former LDP incumbents, headed by Tsutomu Hata, and the New Party Harbinger also formed by break away LDP incumbents, led by Masayoshi Takemura. The 1993 election also witnessed another newly formed party founded by Morihiro Hosokawa, who was the former governor of Kumamoto Prefecture and a member of the House of Councilors.Footnote 4

This election produced the first non-LDP government in 38 years, but the anti-LDP coalition that allowed this to occur did not last long as party splits, dissolutions, and mergers continued until the 1996 election held in October of that year. New parties competing in this election included the New Frontier Party, a merger of several smaller parties, and the DPJ, which formed a month before the election mostly out of anti-LDP incumbents, including some formerly associated with the New Party Harbinger and some erstwhile Socialists.

The DPJ turned in less than optimal performances in the next three elections of 2000, 2003, and 2005, obtaining 127, 177, but then 113 seats respectively in each. Four years later in 2009, however, the DPJ swept the LDP out of power by obtaining 308 Diet seats to the LDP's 119. While party leader Yukio Hatoyama become Prime Minister with much popularity and fanfare, the DPJ's electoral fortunes quickly soured, and the party began experiencing a secular decline that continued until its dissolution in 2017. The DPJ's decline began with many incumbents exiting and forming new splinter parties, and these changes led the DPJ to enter the 2012 election with only 230 of the 308 incumbents it had in 2009.

These small- and large-scale changes that occurred in postwar Japan have been addressed in the scholarly literature in both descriptive and historical formats as well as in more theoretically informed analyses. The former is represented by such studies as those by Curtis (Reference Curtis1989, Reference Curtis1999) and Hrebenar (Reference Hrebenar2000),Footnote 5 while the latter group of scholars – whose study informs the research in this paper – was motivated primarily by the larger shifts that began with the election of 1993. Specifically, Cox and Rosenbluth (Reference Cox and Rosenbluth1995) noted that electoral support considerations were the most important factors that led a substantial number of LDP members to join newly created parties in 1993, while Reed and Scheiner (Reference Reed and Scheiner2003) argued that legislator motives were mixed and included both electoral concerns but more importantly policy interests, particularly, a strong commitment to political reform. Nyblade (Reference Nyblade2012) focused on the DPJ exits that occurred prior to the election of 2012 and found that these exits were a mixture of electoral, office, and policy concerns but also that impacts of these factors were not monotonic.Footnote 6

Another analysis that focused on the events leading up to the election of 1993 and beyond was by Kato (Reference Kato1998), who reformulated the exit, voice, and loyalty perspective of Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970), by arguing that legislators considered switching parties for one additional reason, specifically, concerns with the quality of the public goods their political party produces.Footnote 7 Because this is a major part of a political party's reputation, it can lead elected officials to consider exercising an exit option, even in the face of considerable electoral risk.

This scholarship has been informative to be sure, but it has generally not considered how electoral institutions and available party alternatives lead incumbents to weigh their party exit decisions and the benefits they hope to obtain against the risks associated with moving to a new organization.Footnote 8 We know from Rosenbluth and Thies (Reference Rosenbluth and Thies2010) that Japan's parallel electoral system put in place in 1994 significantly changed the incentives faced by parties and individual politicians, making Japanese elections less personalistic and more oriented on policy. Nonetheless, we still have not explored how the altered incentives attendant to this parallel system affect party exit decisions, especially how the benefits associated with the factors that motivate legislators' decisions to consider switching political parties are weighed against sources of electoral risk.

This is particularly important since the rules under which this election was held involved a reduced amount of electoral risk for some legislators but not for others. The exit decisions of 88 DPJ incumbents in the 2017 snap election will allow us to accomplish this because we will be able to control for the individual factors that motivated legislators to contemplate switching parties in light of the electoral risks they faced. Our effort begins with a discussion of this 2017 snap election, particularly those features that make it an appropriate contest to calibrate the impact of alternative party choices, electoral institutions, and personal motivations on exit decisions.

2. Japan's 2017 snap election and the affiliations of DPJ incumbents

The 2017 snap election was called by former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo more than 14 months prior to its constitutionally required time, and it involved competition for Diet seats that included both old and new political parties. Indeed, 3 days before the House of Representatives was formally dissolved, former Tokyo Governor, Koike Yuriko, announced the formation of a new political party, the Party of Hope (POH) or ‘Kibo no Toh,’ and 5 days after the House of Representatives was dissolved, Edano Yukio, the DPJ's General Cabinet Secretary, announced that he would form another new political party, the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP).

These two parties were created to serve as alternative parties for incumbent members of the DPJ, who were in a political party that had essentially reached the end of a long period of electoral decline. The DPJ's decline affected its remaining 88 incumbents, who were forced to confront the decision of how to compete in this election. This is because its leader, Maehara Seiji, announced that the DPJ would not endorse any candidates in this upcoming election, and, as a result, DPJ incumbents were forced to compete as unaffiliated candidates or join either the POH or the CDP.

Given the scheduling of this election, DPJ incumbents had much less time to prepare than if it was scheduled closer to its constitutionally prescribed date, and this is also true for leaders of both the POH and the CDP, who barely had time to help endorsees be ready to compete successfully for the Diet seats they held. Naturally, these DPJ incumbents would enter this contest with different levels of electoral strength, which forced them to consider the risk level attendant to their decisions to join one party or the other or compete without a party endorsement. These considerations would also have to be weighed not only against these members' own policy preferences, but also against the policy preferences of the leaders of these two new alternative parties they might be interested in joining. This is important because it was not enough simply to choose which party they wanted to join based on their electoral chances and their individual policy preferences because Koike, in particular, had clear preferences with respect to the policy profiles of exiting DPJ incumbents she preferred to welcome into the POH.

The former Tokyo governor enjoyed growing popularity up to the election that was arguably greater than former DPJ leader, Edano, which made the POH an attractive alternative, but the former Tokyo governor had specific policy preferences that could raise concerns among at least some DPJ incumbents. Indeed, while she held progressive positions on elevating the status of women and imposing a carbon tax, both to improve the quality of Japan's environment and to reduce its contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, she also held many policy positions that were conservative and nationalist. Among these was her support for official visits to Yasukuni Shrine and history textbook reform, but most notable was her favorable stance on revising Article 9 of the postwar Japanese constitution so that Japan could finally pursue a security policy of collective self-defense.

Her position on Article 9 very possibly complicated the exit decisions of some DPJ incumbents because, while many wanted this party's endorsement for the 2017 election, others did not want to be associated with Koike's advocation of constitutional revision. At the same time, the POH leader was not interested in extending endorsements to those DPJ incumbents who strayed very far from her preferred policy profile. Not having policy preferences that lined up with the POH's leaders did not mean that exiting incumbents had to compete in this election as unendorsed candidates because Edano's CDP was less strict in terms of the policy profiles of former DPJ legislators who would be welcomed into his start-up political party.

What is important here is that we expect decisions to join the POH – or the CDP for that matter – to depend on incumbents' level of opposition to Koike's policy preferences, making strong opponents more likely to seek membership in Edano's CDP. Overall, for DPJ incumbents who were weakly opposed or unopposed to Koike's position, their exit decisions should be less influenced by their policy preferences and, thus, rendered more in obeisance to an office-seeking imperative, that is, how their extant electoral support levels related to the risk of exiting. On the contrary, for those incumbents who were strongly opposed to Koike's position, they would be more likely not to choose, nor be allowed to move to, this start-up party and have to seek a different alternative.

While DPJ incumbents were naturally concerned with both remaining in office and with promoting preferred policies,Footnote 9 this does not mean that these two factors shared equal weight across all DPJ incumbents. This is because some candidates were strict policy seekers, others strict office seekers, and still others were motivated by how these influences interacted with each other.Footnote 10 This means that we must consider both of these individual factors and the potential impact of available alternative parties and electoral institutions. As suggested above, electoral risk would be a function of a candidate's support levels, where high-support level candidates faced less risk compared to weaker candidates, but even electorally weaker candidates could face lower levels of electoral risk compared to others with similar levels of support. This is because Japan's electoral system is a parallel system where office seekers compete for lower house seats in either single-member districts (SMDs) or as a member of a party list a larger proportional representation (PR) district.

In many if not most cases, candidates picked one or the other as the place they would compete for a Diet seat, but there were also incumbents who competed for an SMD seat while simultaneously having their name put on a party's list of PR candidates. This latter group of incumbents had dual or overlapping candidacies, which meant that, if they did not obtain an SMD seat but were high enough on the party list, they could still obtain a seat in their respective PR district. Incumbents who lost an SMD seat but got elected as a member of their party's PR list became known as ‘Zombie Incumbents,’ because they were able to rise from their electoral deaths after losing an SMD seat through the PR portion of Japan's parallel electoral system.Footnote 11

3. Policy, party choice, and electoral risk in exit decisions

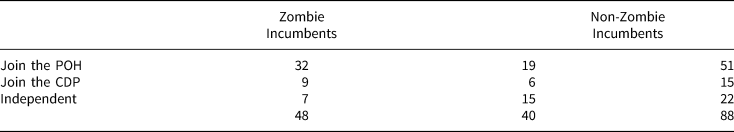

To calibrate how individual motivating factors were weighed against the electoral risks associated with Japan's electoral institutions and party alternatives in the exit decisions of DPJ incumbents, we first focus on Japan's electoral rules. Again, Japan's parallel system allows candidates to pursue dual or overlapping candidacies, whereby candidates choosing this option are expected to experience less electoral risk than those who chose to compete strictly in one of the system's SMDs.Footnote 12 In this snap election, many DPJ incumbents competed for Diet seats with an overlapping candidacy, and these incumbents as well as those who did not are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Exit decisions of Zombie vs non-zombie incumbents

χ 2 = 6.1463.

PR > χ 2 = 0.0462.

We observe that 48 out of 88 (55%) of these DPJ incumbents were Zombie winners, while 40 out of 88 (45%) were exclusively SMD winners, and, thus, did not benefit from the reduced electoral risk the Japanese electoral system afforded. We also observe from the data in the table that 67% of Zombie incumbents – 32 out of 48 – decided to join Koike's POH while one-fifth joined the CDP and the remainder (15%) competed without party endorsement. Moreover, 48% of SMD-only incumbents – 19 out of 40 – moved to the POH, 15% to the CDP, with nearly 40% seeking a Diet seat without a party endorsement.

These data suggest strongly that Zombie incumbents were much more likely to join the POH compared to their SMD counterparts, which tells us that Japan's electoral institutions were an important factor influencing DPJ incumbent motivations to join the POH, while SMD-only incumbents were much more likely to compete without a party's endorsement.Footnote 13 However, to investigate the statistical significance of this relationship, we performed a χ 2 test on the relationship between institutional risk and exit choice, and the results produced a χ 2 of P > 0.0462, which indicates a statistically significant relationship at the 95% level of confidence.

These results indicate that the institutional impacts in this election could be a direct influence on exiting DPJ incumbents' decisions to join the POH or seek their Diet seats without a party's endorsement but not to join the CDP. Nonetheless, we need to expand our analysis and explore the possibility that more nuanced relationships exist when exiting legislators weigh the benefits they hope to obtain by switching parties against all sources of electoral risk. To accomplish this, we need to refocus our attention on available party alternatives while controlling for the influence of the individual factors discussed above as well as other control variables.

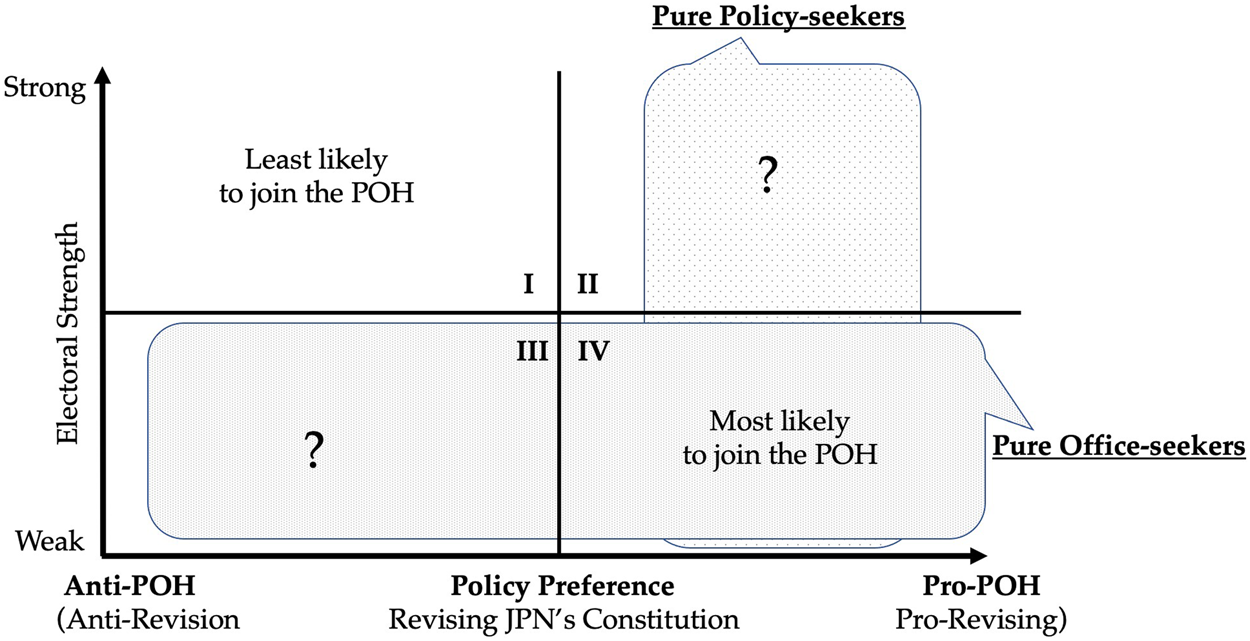

As mentioned above, the individual factors we consider in this analysis are the strength of an incumbent's support levels entering the 2017 election as well as candidates' policy preferences. Figure 1 presents a theoretical illustration of these relationships as well as our expectations for how they will affect an incumbent's decision of whether to join the POH or the CDP or compete in the election without a party endorsement. Specifically, the x-axis in the figure captures an incumbent's policy preference, in this case, his/her position on constitutional revision (PCR), which was the most important policy factor accounting for a DPJ incumbent's decision to join the POH. The y-axis shows the electoral strength of an incumbent, measured as his/her vote share in the 2014 lower house election. This theoretical representation of the interplay of policy preferences and electoral risk leads to two clear behavioral expectations and two that are less clear but will be investigated more deeply in the empirical analysis we conduct below.

Figure 1. Policy position, electoral strength, and the decision to exit.

The variable of interest here is our expectations about the likelihood that a candidate would move to Koike's POH prior to the 2017 lower house election.Footnote 14 Here, we categorized 88 DPJ incumbents into four types in terms of their policy preference (x-axis) and electoral strength (y-axis). We hypothesize that, if former DPJ incumbents are purely policy-seekers, then these incumbents will be guided by an issue profile closer to the POH's (i.e., those categorized in quadrants II and IV) and they should be more likely to join the POH, regardless of their electoral strength.Footnote 15 On the contrary, if former DPJ incumbents are purely office-seekers, then those electorally weaker incumbents (i.e., those categorized in quadrants III and IV) should be more likely to join the POH, regardless of their policy profile.

In reality, however, DPJ incumbents are most likely to be neither pure policy seekers nor pure office seekers, which means that most fall somewhere in between these two pure groupings. As a result, we hypothesize that those electorally stronger incumbents holding policy positions contrary to the preferences of POH leader, Koike Yuriko, and fall into quadrant I should have lower likelihoods of joining the POH. On the contrary, we expect that those electorally weaker incumbents holding pro-POH policy positions, that is, those who fall into quadrant IV, should have a higher likelihood of joining the POH.

For incumbents who noted they oppose revising the Japanese constitution, their exit decisions will be more influenced by concerns with their electoral strength. Specifically, if candidates are against revising Japan's constitution and their vote shares in the 2014 lower house election are small, that is, they are electorally weak, then they are increasingly likely to move to the POH so that they can take advantage of that party's popular leader, increasing their likelihood of winning a seat in this snap election.Footnote 16 However, if DPJ incumbents are against constitutional revision and their electoral margins in the 2014 lower house election were large, that is, they were electorally strong, they may not be as inclined to move to the POH.Footnote 17 Specifically, such incumbents may still exit to the POH because doing so will help ensure their winning seats, or they may decide to join the CDP or they may simply to decide to compete without a party endorsement.

While these probabilistic relationships are straightforward, we are less certain about how those incumbents categorized in quadrants II and III in Figure 1 will behave in their decision to join one of the available start-up parties or compete without a party endorsement. We assume that these incumbents will be motivated by mixed incentives in their exit decisions, weighing both their policy preferences and electoral strength in light of these factors' impact on their ability to secure a Diet seat in this snap election. Given that their calculus is based on how these factors interact, we can say that incumbents in quadrant III are likely to have a higher probability of joining the CDP than the POH and that incumbents in quadrant II are more likely to join the POH than those in quadrant III. However, to be more certain of these expected relationships, we explore them empirically in more detail in the next section.

4. The impact of policy, party alternatives, and electoral risk on exit decisions

The statistical analysis we conduct below is designed to disentangle the relationships that exist between how incumbents considering party exits weighed the individual benefits they expected to receive against the electoral risks they encountered from both the types of start-up parties available to them and Japan's unique electoral system. To disentangle these relationships and calibrate the influences of those factors we discussed above, we must first note that exiting DPJ incumbents who decided to compete in the 2017 snap election had three choices before them. They could try and join one of the two new start-up parties,Footnote 18 Koike's POH or Edano's CDP, or they could enter the 2017 election without a party endorsement.

The multiple choices before DPJ incumbents then make our variable to be explained a multi-valued categorical variable. Because of this, to calibrate the influence of those risk and policy factors we discussed above, as well as any control variables that we include to avoid omitted variable bias, we must employ a multinomial logit analysis. Our analytic effort then focuses on whether a DPJ incumbent joined one of the two available start-up parties (the POH or the CDP) or competed in the 2017 election as an unaffiliated candidate. Because the dependent variable is a categorical variable with three values, we note that exit takes on a value of 1 if a former DPJ incumbent joined the POH, 2 if he/she joined the CDP, or 3 if the former DPJ candidate entered the election without a party endorsement.

As shown in Table 1, 51 out of 88 joined the POH, which as mentioned above, tells us that more than half (58%) of the DPJ's incumbents moved to Koike's POH.Footnote 19 When defined as what explains an incumbent's decision to join the CDP, we observe that 15 (17%) out of 88 of the DPJ's incumbents moved to the CDP, which means that fewer than one-fifth of exiting incumbents joined Edano's start-up party.Footnote 20

With the variable to be explained defined and categorized for the analysis, we turn next to the variables that we include in our models to capture the impacts associated with electoral strength, policy preferences, and other controls to avoid omitted variable bias in our models. The first of these individual factors we include in the models we estimate below refers to incumbents' policy preferences where we focus on incumbents' views with respect to the following four issues:

(1) revising the Japanese Constitution (PCR),

(2) collective self-defense (COLLECTIVE),

(3) level of Japan's defense capability (DEFENSE), and

(4) Japan initiating a preemptive strike (PREEMPTIVE).

Each of these four variables captures an aspect of DPJ incumbents' policy preferences, and they are all calibrated on a five-point ordinal scale. Specifically, a value of 1 refers to an anti-POH preference on these issues; 2 refers to an incumbent's position being moderately anti-POH; 3 indicates an incumbent's position being indifferent with respect to each issue; 4 refers to an incumbent's position being moderately pro-POH; and 5 refers to an incumbent's position being pro-POH. These policy preference variables are based on data collected in the Asahi Today Survey of Diet Members taken in 2014.Footnote 21

The second individual-level factor we consider in this analysis is a DPJ incumbent's electoral strength entering the 2017 snap election, what we refer to as that candidate's electoral margin. This indicator is intended to capture the level of risk associated with an individual incumbent's decision to compete as an unaffiliated candidate or with an endorsement from one of the available start-up parties. It is measured as the electoral margin of the exiting incumbent compared to the runner-up in the 2014 House of Representatives Election. The larger a margin, the stronger an SMD incumbent was entering the 2017 election. We calculate candidates' electoral margins for SMD incumbents and Zombie incumbents on the same scale.

For example, let's suppose there are two candidates in an SMD, candidate S (SMD winner) and candidate Z (Zombie winner). Candidate S received 100,000 votes and candidate Z received 90,000 votes. The margin for candidate S is calculated as candidate S's votes divided by candidate Z's votes: 100,000/90,000 = 1.11. The margin for candidate Z is calculated as candidate Z's votes divided by candidate S's votes: 90,000/100,000 = 0.9.

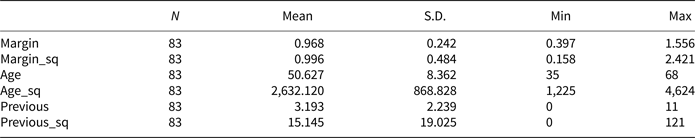

Thus, the SMD winner's margin is always larger than 1, and Zombie winner's margin ranges from 0 to less than 1. The larger the margin, the electorally stronger the incumbent would be entering the snap election. Calculated this way, we can compare incumbent's relative electoral strength, regardless of the two different types of incumbents. The electoral margin used for Zombie incumbents is equivalent to ‘Sekihai ratio’ officially used to select Zombie incumbents in Japan's Lower House elections since 1996. The average 2014 margin captured by DPJ incumbents was 0.97 where this measure of electoral strength ranged from a low of 0.397 to a maximum of 1.556. In our analysis, however, we use both the actual and squared values of this ‘Sekihai ratio,’ because while it may not be monotonic and impact exiting legislators' choices in a nonlinear manner, it may also be linear and including both terms is the appropriate way to capture these possibilities (Nyblade, Reference Nyblade2012: 26).

The multinomial logit models, we estimate below contain two additional control variables, and the first of these is designed to capture an incumbent's level of electoral experience, specifically, how accomplished that incumbent has been accumulating electoral victories. This variable (Previous) then is constructed as an integer capturing the number of past electoral victories an incumbent had prior to entering the 2017 snap election. Electoral victories for DPJ incumbents averaged 3.23 where the minimum value was 0 and the maximum number of electoral victories for a DPJ incumbent was 11.Footnote 22 We included both the integer and squared values of this variable in our models because we wanted to determine if its relationship with DPJ incumbents' exit decisions is monotonic and linear or nonlinear. The second control variable is the age of incumbents competing in this snap election. The average age of these incumbents was 51, and the youngest incumbent was 35 while the most senior was 68. In our analysis, we included both the integer and squared values of an incumbent's age, because we also want to be able to determine if its impact is monotonic or nonlinear.

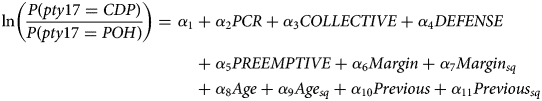

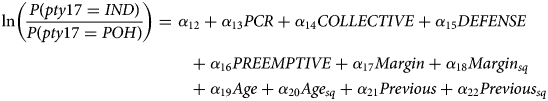

With all explanatory factors defined, we estimate four multinominal logit models, where model 1's and model 2's baseline category is an exiting legislator choosing the POH and model 3's and model 4's baseline category is an exiting legislator choosing CDP.

4.1 Model 1 (baseline = POH)

4.2 Model 2 (baseline = POH)

4.3 Model 3 (baseline = CDP)

4.4 Model 4 (baseline = CDP)

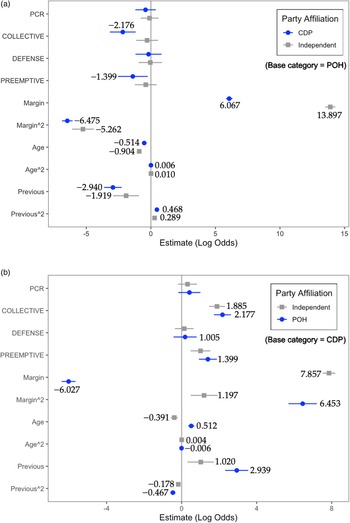

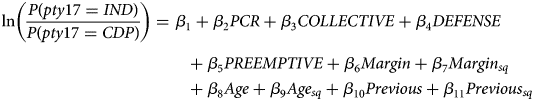

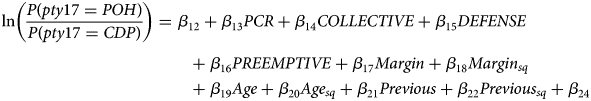

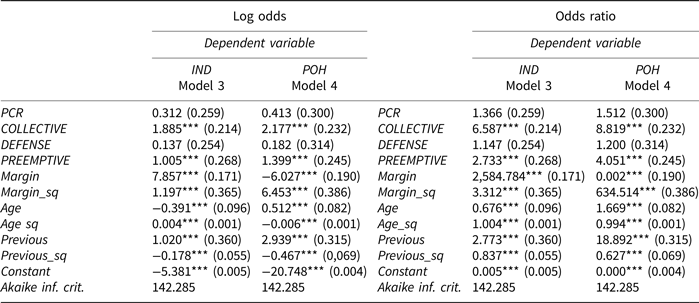

Figure 2, which is divided into two sub-figures, shows the results of estimating our four multinomial logit models. Specifically, it contains the log odds of the variables we included in all four models, which because they take on positive and negative values offer a clear way to determine if a factor raises or lowers the odds of an incumbent choosing the CDP or competing without an endorsement over joining the Party of More. Specifically, the estimates in the figure indicate the effect of a unit increase in the value of a predictor variable on the odds of selecting one of the two specified categories on the dependent variable instead of the correct response, which is designated as the base category. In addition to the value of the log odds ratios of each of the models' explanatory variables, the data in Figure 2 also contain error variances around each log odds ratio, which provide a visual method to distinguish those estimates that are statistically significant from those that are not. Our examination of the impact of the policy, risk, and control factors on exit decisions begins with how the security policy preferences of DPJ incumbents affected their exit decisions.

Figure 2. Results obtained by estimating multinominal logit models 1–4. (a) Log odds for models 1 and 2. Note: The details on these results (log odds and odds ratio) are presented in Appendix 5. (b) Log odds for models 3 and 4. Note: The details on these results (log odds and odds ratio) are presented in Appendix 6.

5. Discussion: policy preferences, electoral risk, and exit decisions

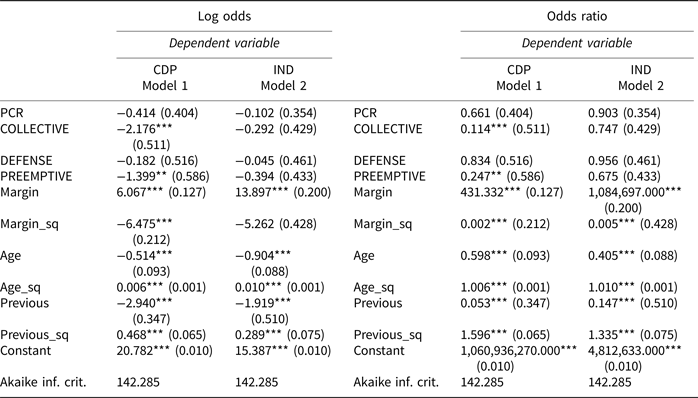

Again, the data in Figure 2a refer to the log odds of DPJ incumbents choosing the CDP or having no party affiliation in the 2017 snap election instead of entering that contest with a POH endorsement, and this is because, in models 1 and 2, we set the baseline of the outcome variable (pty17) as the POH category. To determine the impact of an incumbent's security policy preferences, we first identify which estimates on the policy indicators are statistically significant, and we observe from the figure that an incumbent's position on the collective self-defense (COLLECTIVE) and preemptive strike (PREEMPTIVE) issues were statistically significant among the four included in the models. Unit changes in each of these policy variables indicate that a DPJ incumbent's position moved closer to that of the POH leader, Koike Yuriko.

The log odds on the COLLECTIVE variable is −2.176 (equivalent to 0.114 in odds ratio), which tells us that when a DPJ incumbent has one unit favorable preference to the POH on collective self-defense, the likelihood that he/she would exit by joining the CDP reduced by 0.114 times, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the POH.Footnote 23 We also observe from this figure that the log odds on the PREEMPTIVE policy variable is −1.399 (equivalent to 0.247 in odds ratio), which indicates that a unit increase in this policy preference reduces likelihood that a DPJ incumbent would join the CDP over the POH by 0.247 times, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the POH.Footnote 24

The results presented in Figure 2a also make clear that there were other factors that lowered the likelihood that an exiting legislator would join the CDP over the POH. The reference here is to the impact of an incumbent's electoral margin, both its linear and nonlinear versions, which were both statistically significant. What is important here is that both measures of a DPJ incumbent's electoral margin affected their exit decisions, but more importantly they did this in different ways.

Specifically, the Margin variable for a DPJ incumbent joining the CDP carried a monotonic impact of 6.067 in log odds (equivalent to 431 in odds ratio), in that a unit increase in Margin raised the likelihood of a legislator joining the CDP over the POH by 430 times. The same trend is observed for a DPJ incumbent joining the independent category. What this means is that the stronger a candidate's electoral margin, the more likely that candidate was to join the CDP or compete without a party endorsement, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the POH. That the coefficients on Margin-squared variable are both negative (−6.475 and −5.262) and statistically significant for the CDP and competing without endorsement means that an incumbent's margin is related to the outcome variable with a decreasing level of impact.

Albeit much smaller and somewhat confounding, we witness a similarly dual impact with respect to a DPJ incumbent's number of previous victories. Both the linear and nonlinear versions of this variable, which captured the impact of the number of a candidate's previous victories, were statistically significant. Specifically, the Previous variable for a DPJ incumbent joining the CDP carried a monotonic impact of −2.940 in log odds (equivalent to 0.053 in odds ratio), in that a unit increase in this factor reduced the likelihood of a legislator joining the CDP over the POH by 0.053 times.Footnote 25 What this means is that the more experienced a candidate is, the less likely that candidate was to join the CDP or compete without a party endorsement, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the POH. That the estimates on both the linear and squared Previous variable are both positive (0.468 and 0.289) and statistically significant for the CDP and the unendorsed categories means that an incumbent's margin is related to the outcome variable at a decreasing level of impact.

Finally, while a DPJ incumbent's age did have an impact on whether that candidate joined the CDP or competed without an endorsement instead of joining the POH, its impact was strictly monotonic. Specifically, the Age variable for a DPJ incumbent joining the CDP carried a monotonic impact of −0.514 in log odds (equivalent to 0.598 in odds ratio), in that a unit increase in Age reduced the likelihood of a legislator joining the CDP over the POH by 0.598 times.Footnote 26 A similar trend is observed for a DPJ incumbent joining the independent category. What this means is that the older the candidate, the less likely that candidate was to join the CDP or compete without a party endorsement, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the POH. That the coefficients of Age squared are not statistically significant implies a strict monotonic relationship between Age and the outcome variable, pty17. This is an important finding in that it tells us that, all things being equal, older candidates were more inclined to make the safer choice of joining Koike's POH rather than Edano's CDP or entering the 2017 contest without an endorsement from the POH.

When we estimate models 3 and 4, those where the baseline category is the CDP category, we obtain results that indicate the likelihood of a DPJ incumbent joining the POH and the likelihood of a DPJ incumbent competing without a party endorsement, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the CDP.Footnote 27 As expected, we observe that moving closer to Koike Yuriko's position on collective self-defense and agreeing with Japan engaging in a preemptive strike increased the likelihood that a candidate would select the POH and compete without a party endorsement, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the CDP.Footnote 28

Specifically, the COLLECTIVE variable for a DPJ incumbent joining the POH carried an impact of 2.177 (equivalent to 8.9 in odds ratio), in that a unit increase in COLLECTIVE increased the likelihood of a legislator joining the POH over the CDP by 8.9 times. The COLLECTIVE variable for a DPJ incumbent joining the independent category carried an impact of 1.885 in log odds (equivalent to 4 in odds ratio), and what this means is that a unit increase in COLLECTIVE increased the likelihood of a legislator joining the independent over the CDP by 4 times.

The PREEMPTIVE variable for a DPJ incumbent joining the POH carried an impact of 1.399 in log odds (equivalent to 4 in odds ratio), in that a unit increase in PREEMPTIVE increased the likelihood of a legislator joining the POH over the CDP by 4 times. The PREEMPTIVE variable for a DPJ incumbent joining the independent category carried an impact of 1.005 in log odds (equivalent to 2.7 in odds ratio), in that a unit increase in COLLECTIVE increased the likelihood of a legislator joining the independent over the CDP by 2.7 times.

We also observe from the results in Figure 2b that a DPJ incumbent's electoral margin was an important factor that influenced that candidate's exit decision. Specifically, we observe that there were significant monotonic impacts of a candidate's electoral margin in that a unit increase in the linear version of a candidate's electoral margin increased that candidate's likelihood of running without an endorsement by 2585 times, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the CDP.Footnote 29 However, this is not the case for a DPJ candidate joining the POH, where a 1 unit increase in the linear version of a candidate's electoral margin decreased that candidate's likelihood of joining the POH by 0.002 times, compared to another DPJ incumbent who joined the CDP.Footnote 30 The impact of the squared version of the electoral Margin variable was positive both in the case of an incumbent joining the POH and the case of a candidate entering the 2017 contest unendorsed rather than joining the CDP, implying that an incumbent's Margin is related to the outcome variable with increasing margin. We observe from the results shown in Figure 2b that the number of an incumbent's previous victories and age also carried impacts that corresponded to the manner in which these explanatory variables worked when the base category was the POH.

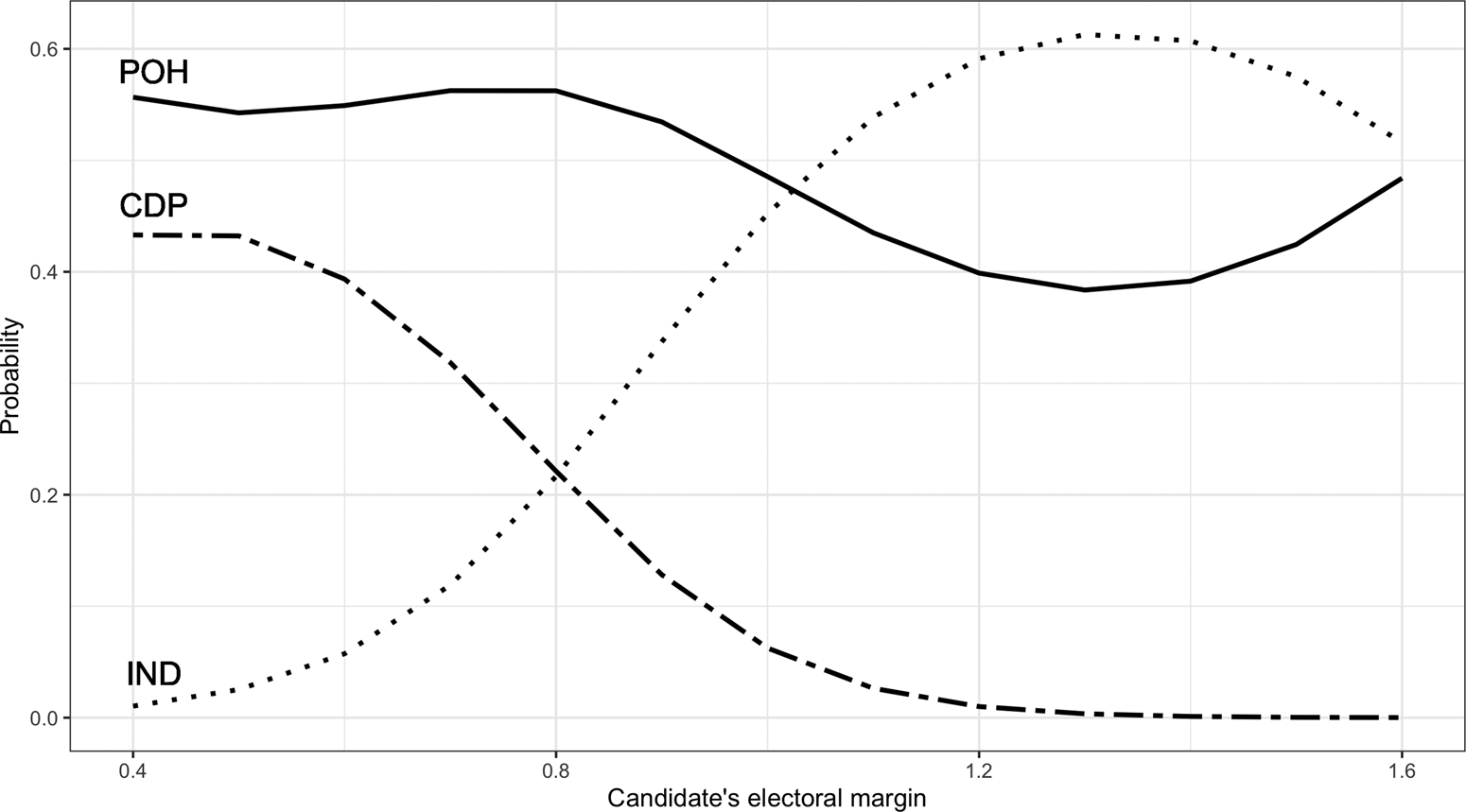

The impacts associated with candidates' security policy preferences in models 3 and 4 were as expected in that the closer a DPJ incumbent was to the preferred position of POH leader, Koike Yuriko, the more likely that candidate was to join the POH but compete neither as an unaffiliated candidate nor as a member of the CDP. These relationships were clear in Figures 2a and 2b, but our analysis also revealed a more nuanced relationship with respect to candidates' electoral strengths, which were measured essentially as their Sekihai ratios. We explored these relationships more closely in Figure 3 which shows averaged probabilities of joining one of the two available parties or remaining unaffiliated (y-axis) by Sekihai ratios (x-axis) with other variables remaining fixed at their means.

Figure 3. Averaged probabilities of joining parties by electoral margin. Note: In this simulation, we fixed the control variables at their means.

The data in Figure 3 support four important points. The first of these concerns the fact that changes in legislators' electoral margins did have an impact on all three categories of exit decision, but as witnessed in the averaged probabilities the curves are based on, the extent of these impacts were different for each category. Second, as we intimated in the discussions provided above, politicians who joined the CDP behaved more like ‘office-seekers’ compared to DPJ incumbents whose exit decisions involved other alternatives. For legislators who joined the CDP, those who were weakest electorally (Sekihai ratio = 0.4) had a 43.3% likelihood of joining the CDP, but as these legislators' electoral strength increased to its highest level (Sekihai ratio = 1.6), their likelihood of joining the CDP dropped nearly to zero (0.009758%).

Third, in the same way that variations in a DPJ incumbent's electoral margin strongly impacted the likelihood of that candidate exiting into the CDP, different electoral margin levels also strongly impacted the likelihood of a candidate entering the 2017 snap election without a party endorsement. We observe from Figure 3 that incumbents with the lowest electoral margins had a near zero likelihood of competing as an unendorsed candidate. This likelihood, however, changed dramatically as electoral margins increased. Indeed, many incumbents with margins greater than 1 were more than 60% more likely to compete in 2017 without a party's endorsement.

Finally, as the analysis and discussions provided above have shown, DPJ incumbents who joined the POH behaved more like ‘policy-seekers’ compared to those who sought other exit options. The initial evidence for this conclusion in Figure 3 is simply the fact that electoral margins were much less impactful on this category of exiting DPJ incumbents than it was for those who joined the CDP or competed as unendorsed candidates. Indeed, we observe that legislators who joined the POH, did so at rates that ranged from 38.4 to 56.3% for the same extensive range of electoral margin values.

6. Conclusion

Decisions to leave one's current political party for another organization is a decision that it attendant to electoral risk. Because of this, incumbent legislators who are contemplating such a decision will weigh the benefits they hope to obtain from changing parties or competing without an endorsement against the risks of this decision not being successful. Among the benefits that some legislators facing exit decision hope to obtain is to influence some policy outcome, and as a result, some of these decisions are motivated by their positions on important policy issues. Other scholarly research, both on Japan and in broader comparative perspective, has confirmed that both office concerns and policy preferences are important factors in exit decisions. We have confirmed these findings in the analysis we conducted above, but we have contributed to and extended this body of scholarship in two ways.

Most importantly, we have shown that the nature of the alternatives available to legislators contemplating exit decisions will have a strong impact on how electoral risk and policy preferences operate in their decisions to change party organizations. Specifically, legislators who tend to be office seekers may have different party alternative preferences compared to those who are motivated primarily by policy preferences. We provided evidence that DPJ incumbents who chose the POH as their new institutional home were much more influenced by policy rather than electoral concerns in their exit decision. On the contrary, those DPJ incumbents who preferred to join Edano's CDP or compete without a party affiliation behaved much more as office seekers, that is, being influenced greatly by their own levels of electoral strength.

What is also important about the findings presented above is that, while the nature of available party alternatives will affect how legislators carry out their exit decisions, both individual and institutional factors may complicate the patterns that this general finding manifests. We observed in the results presented above that such factors as candidates' ages and the number of times they have been elected affected their exit decisions in both monotonic and nonlinear fashions. In addition to this and perhaps more importantly, the fact that electoral risk was identified to be less important for those choosing Koike's POH may be due to factors not often identified as directly impacting party switching decisions.

The reference here is to Japan's unique electoral system, which reduced risks for those who pursued overlapping candidacies compared to those candidates who competed in an SMD without simultaneously getting on a party list for a PR seat. We observe from Figure 3 that incumbents who chose to join the POH were characterized by less variance than those in the other two categories, especially given the range of candidates' electoral margins. The reason for this is that a significant number of these DPJ incumbents already benefitted from the reduced risk associated with pursuing a dial candidacy under Japan's parallel electoral system. As a result, as we shown in Table 1, DPJ incumbents who were Zombie winners were much more likely to move to the POH than to compete without an endorsement or join the CDP.

Finally, in all democracies, party switching is more common than once thought, and such decisions are motivated by certain individual factors that are then weighed against the benefits that will be obtained if the party exit decision leads to a candidate obtaining a legislative seat. While straightforward in concept, the manner in which these relationships obtain are not all the same and, thus, will vary depending on the kinds of alternative choices that are available to legislators who are contemplating joining a new party organization. Our hope here is that a foundation has been laid for continuing to explore these relationships in different democratic nations and under different electoral systems.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi%3A10.7910%2FDVN%2FCFK8FX&version=DRAFT

Appendix 1

Descriptive statistics of variables used in the analysis

Appendix 2

The original survey questions of Asahi-Todai Survey (conducted in November 2014) are presented here. The figure in parenthesis is the number of respondents in that answer category. We reverse these scores in our analysis for the sake of the argument, meaning score 5 is the closest to the POH's policy position.

Q6_1: Defense capability

Should Japan's defense capability be strengthened more?

Please choose of the following 6 alternatives:

1. Agree (N = 301)

2. Agree if anything (262)

3. Indifferent (161)

4. Disagree if anything (44)

5. Disagree (360)

No Answer (63)

Q6_2: Preemptive strike

Should we hesitate to launch a preemptive strike if we anticipate an attack from another country?

1. Agree (N = 72)

2. Agree if anything (150)

3. Indifferent (352)

4. Disagree if anything (101)

5. Disagree (444)

No Answer (72)

Q8: Revising Japanese Constitution (PCR)

Do you agree or disagree to the opinion that we should revise Japanese Constitution? Please choose of the following 6 alternatives:

1. Agree (N = 443)

2. Agree if anything (180)

3. Indifferent (68)

4. Disagree if anything (55)

5. Disagree (371)

No Answer (74)

Q10: Collective self-defense

Do you appreciate or not that Japanese government made a Cabinet decision to allow the nation to exercise its right to collective self-defense

1. Highly appreciate (281)

2. Appreciate if anything (196)

3. Indifferent (35)

4. Not appreciate if anything (67)

5. Not appreciate (546)

No Answer (99)

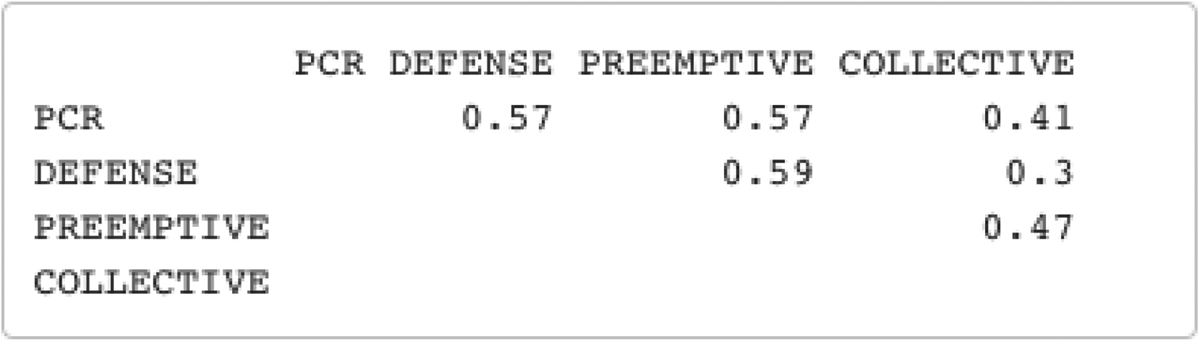

Appendix 3

Correlations among four policy categories

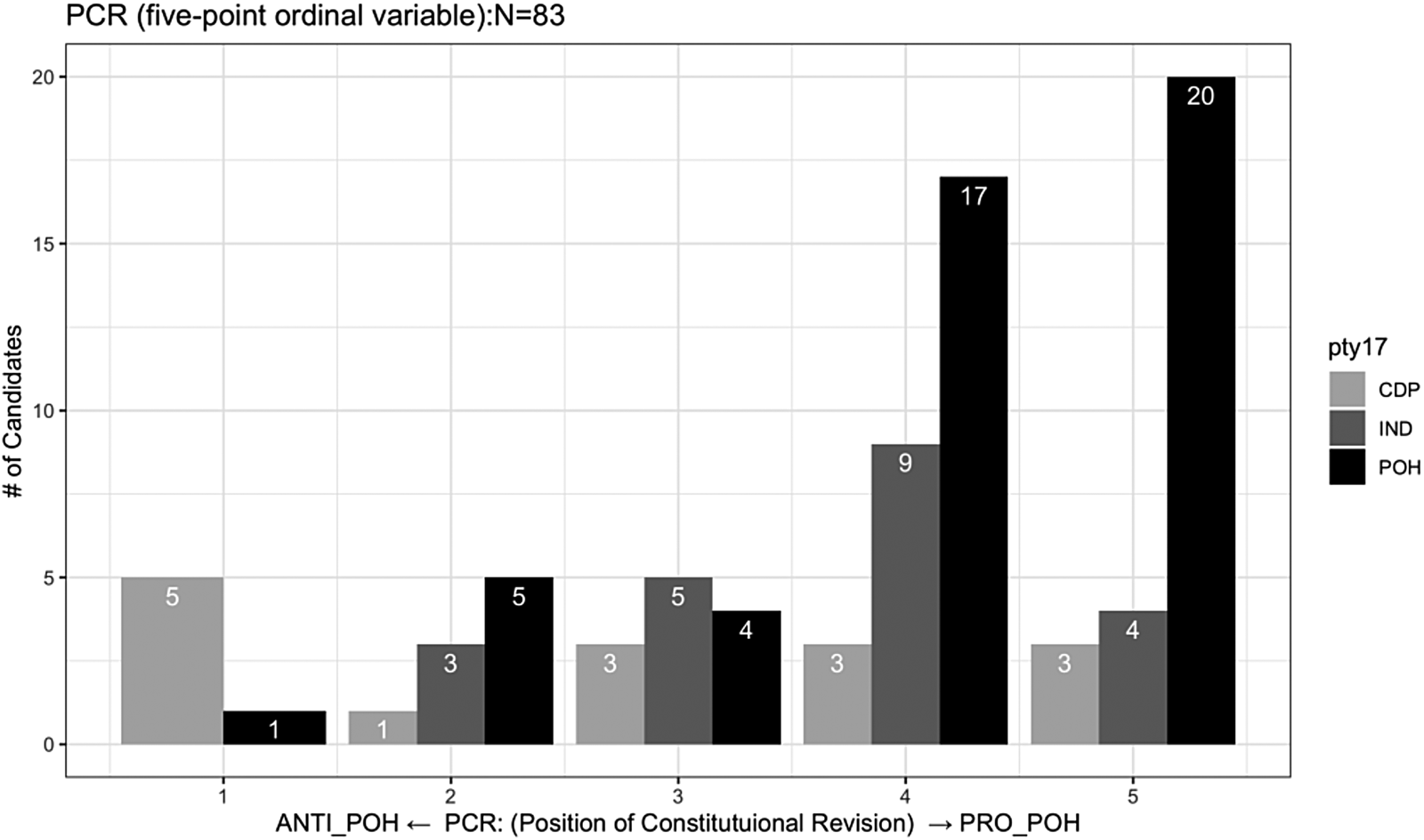

Appendix 4

PCR

Candidate exit decision by revising Japan's Constitutional Policy Position

Note: The total number of the former DPJ members is 88. Five DPJ incumbents are not included in this figure because they failed to answer the PCR question. They joined the POH.

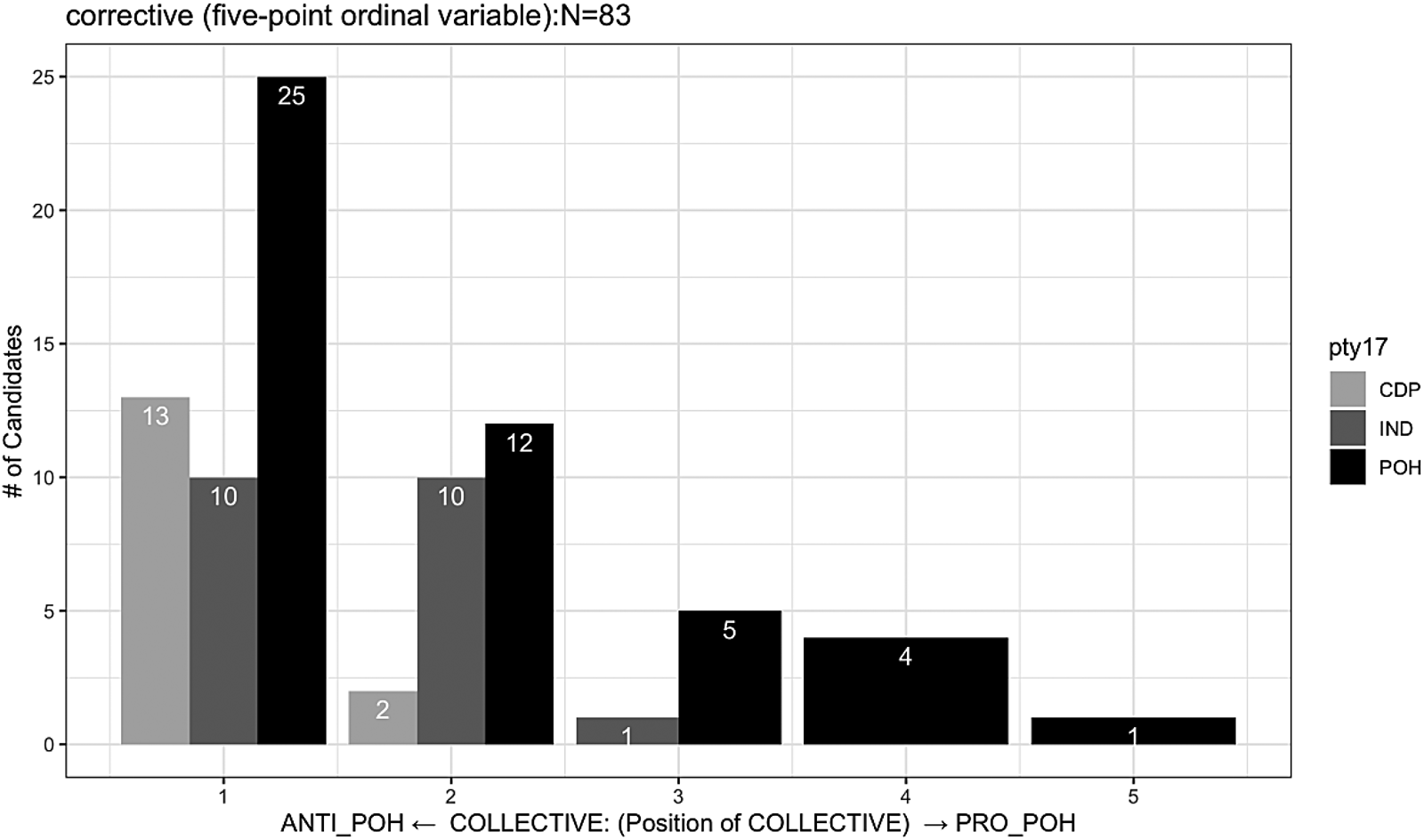

Collective

Candidate exit decision by Japan's Cabinet Decision to allow the nation to exercise its right to collective self-defense

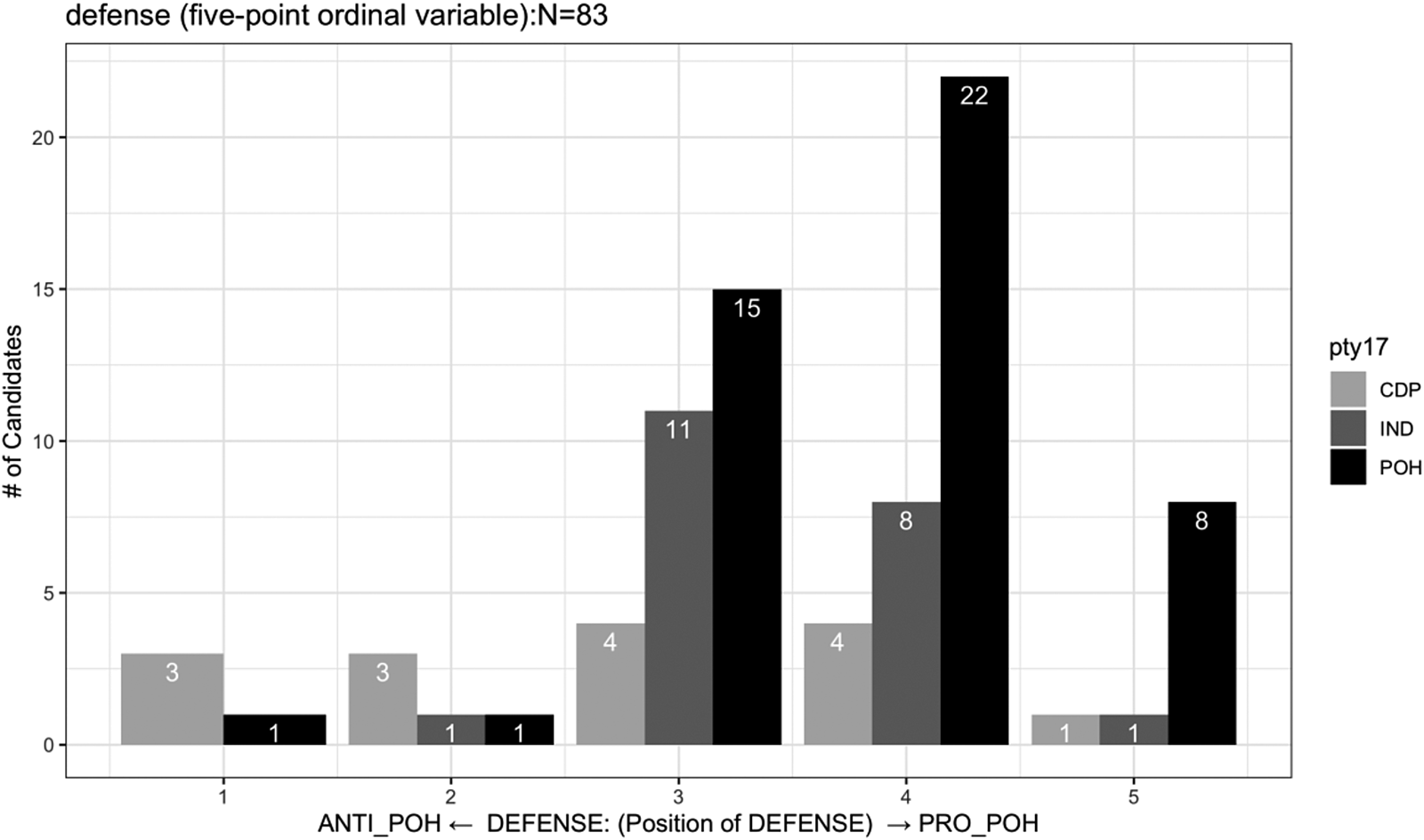

Defense

Candidate exit decision by Japan's defense capability

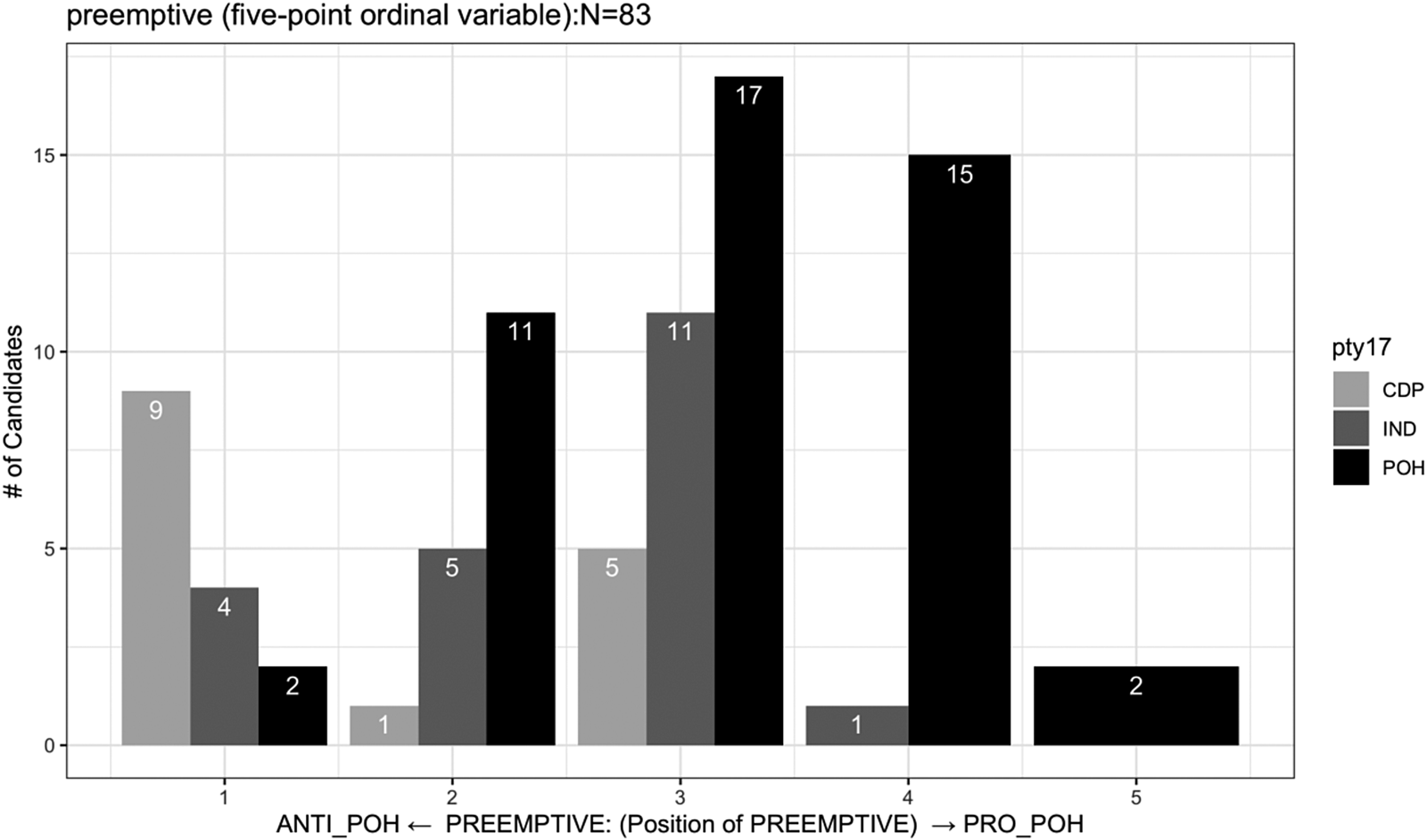

Preemptive

Candidate exit decision by Japan's Cabinet Decision to hesitate launch a preemptive strike if we anticipate an attack from another country

Appendix 5

Results on models 1 and 2

Appendix 6

Results on models 3 and 4

Masahiko Asano is Professor of Political Science at Takushoku University in Tokyo Japan. He has numerous publications in English and Japanese on political parties and elections in Japan. He received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Dennis Patterson is Professor of Political Science at Texas Tech University. He has published on postwar Japanese politics and electoral systems. His Ph.D. is in Political Science from the University of California, Los Angeles.