The stylistic range of one of Finland's most internationally successful composers, Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928–2016) has been well documented. This compositional diversity has led to the image of a rift between works that appeared to ‘validate’ his position as an enfant terrible of Finnish music who helped introduce international modernist techniques to Finland and those that are more familiar and accessible that became known internationally. As an example of the latter, Cantus Arcticus – Concerto for Birds and Orchestra (1972) is greeted with suspicion because of its wide appeal. Kimmo Korhonen regards it as ‘one of his most popular, although hardly artistically most significant works’.Footnote 1 And yet, the issues surrounding Rautavaara's relationship with modernism, tradition, Finnish landscape, and accessibility come together in this piece in a complex and characteristic way. In his autobiography, Rautavaara discusses how his musical output has three threads running through it: modernism, Finnishness, and mysticism.Footnote 2 Cantus, perhaps more clearly than any of his other orchestral works, synthesizes these elements within one piece and, consequently, achieves a broader balance between them. A reconsideration of the role of this misrepresented work in the context of Rautavaara's complicated and original stylistic development from different angles is much needed. After a contextualization of the piece in relation to modernism and its cultural reception, this article considers Cantus through the lens of exoticism and discusses the ways in which landscape and nature shape the piece from Rautavaara's subjective position. It also examines how this inspiration combines with his stylistic renewal following more international experiences of musical modernism, notably serialism and aleatory techniques.

Cantus Arcticus and modernism

Modernism in Rautavaara's music is, in one sense, clearly identified through his use of international, avant-garde musical techniques that were brought to Finland after the Second Word War and are indicative of a cosmopolitan perspective in his music that drew inspiration from abroad. Such techniques include neo-classicism, atonality, serialism, and aleatoricism. Another useful understanding of modernism relevant to Rautavaara is that of ‘moderate’ modernism. A previous study by the present author sets out in detail how this framework applies to Rautavaara's late style,Footnote 3 but it is useful to reintroduce Arnold Whittall's notion of the ‘moderate mainstream’ (versus the ‘modernist mainstream’). Whittall refers to the ‘accommodations achieved between conservatism and progressiveness, the former renewing itself through limited contact with the latter.’Footnote 4 Such a ‘moderate’ position derives from accommodations between newer, more radical, techniques – such as the rejection of tonality – while acknowledging the ‘forms and textures of the tonal past’.Footnote 5 Similarly, J.P.E. Harper-Scott advises against reducing artistic production to binaries of radical and conservative and argues for a middle ground for ‘reactive’ music, between the ‘poles of a “faithful” modernism which confidently asserts the possibility of a new, post-tonal artistic configuration, and an “obscure” response to modernism which utterly rejects the abandonment of tonality and willingly submits to the aesthetic blandishments of the pure commodity’.Footnote 6 These frameworks assist in understanding Rautavaara as an individual, negotiating techniques that are old and new, as well as local and international. A working definition of modernism therefore rests, first, on the identification of new, international compositional techniques and, second, the progressive, individual application of these as part of a larger set of preferences to develop a compositional style.

Arriving at a complete understanding of Cantus requires contextualizing the piece in relation to Rautavaara's experiences of modernism at a time of stylistic reassessment. Work exploring the complicated interactions between landscape, nationalist elements, and musical modernism has so far been orientated towards figures around the turn of the twentieth century. Daniel M. Grimley's examination into the complexities of modernism and landscape form a major part of his study into Carl Nielsen. He contextualizes Nielsen's Third Symphony around ideas of the Funen landscape, which he argues becomes the focal point for a particular kind of modernism articulated by Gunnar Heerup, one that is ‘pointedly unbound by the weight of nineteenth-century musical tradition yet still tied to a more ancient notion of community and land’.Footnote 7 Further, in assessing Vaughan Williams's Pastoral Symphony in relation to ideas of English pastoralism, Grimley challenges the assumption that the symphony constitutes an exclusively English idiom, stating that it actually ‘reveals tensions between inward and outward impulses, between notions of Englishness and a more cosmopolitan Continental European modernism, which in turn reflect a dialogue between abstraction and representation, tradition and innovation, stability and instability’.Footnote 8 As Cantus brings together national influences alongside internationally influenced compositional and stylistic techniques, the multifaceted outlook of the piece shows similar negotiations between the modern and the traditional and a consolidation of techniques channelled towards an individual purpose. In searching for this individuality, Rautavaara had to consider which traditional aspects he valued and saw as being capable of renewal, as well as which modernist techniques were to remain within his arsenal.

In response to a question about how he saw his music as being divided into four stages, Rautavaara came back with a characteristic statement: ‘In my youth I thought it was my duty to learn all the contemporary techniques and methods of “modernism”. The only way to learn them was to compose using them. It took all this to find my own mode of expression.’Footnote 9 For Rautavaara, the legacy of modernism manifested over his long career both as an energetic exploration of new ‘imported’ techniques to Finland such as serialism and aleatoricism (his youthful pursuit of the former placed him at the forefront of Finnish modernism) and as an extended consolidation of those experiences, alongside a broadening of his perspectives. Rautavaara's build up to total serialism can be explained by his intention to find a ‘reliable technique’,Footnote 10 and it is within this larger process that Cantus is to be situated. The piece is often regarded as an anomaly within his output as a whole, another demonstration of his sudden changes in style.Footnote 11 Ultimately, the total serialism in works such as Arabescata was to be too constraining and the ‘non-atonal’Footnote 12 dodecaphony of the earlier Second String Quartet and Symphony No. 3 more fruitful in the long term. The search for a reliable technique therefore took a new direction at the end of the 1960s and a shift in style came with Anadyomene, the Piano Concerto, the two Piano Sonatas, Garden of Spaces and Cantus Arcticus. Rautavaara also stated that, until the 1980s, he considered himself a student.Footnote 13 But the boundary between modernist experimentation and critical, individual mastery is a difficult one to pinpoint. The combination of stylistic and visual elements in Cantus makes this work particularly representative of this transition. Written when Rautavaara was in his mid-forties, the piece cannot really be seen as a student work, but in arguing that it is more musically significant than has previously been credited, it is also necessary to see it within a larger process of acquiring stylistic maturity. This stylistic change around the late 1960s and early 1970s is connected to the larger context of Finnish music, where neo-tonality and a renewed interest in Finnish national subject matter emerged. According to Korhonen, the intensity of a ‘second wave’ of modernism was followed by a ‘receding of the tide’ from the mid-1960s.Footnote 14 Within the extremely concentrated timescale of Finnish musical modernism after the Second World War, sudden changes of musical style are not surprising, revealing a complicated picture of late modernism and a reassessment of nationalism and tradition.

During the 1970s, Rautavaara began experimenting with a new kind of musical modernism in aleatory techniques, which formed another addition to his compositional toolkit. Finns had come to discover these techniques through the Polish avant-garde and, in a decade when Rautavaara had moved away from twelve-tone rows, he developed a tightly controlled use of aleatoric techniques, seen most prominently in Garden of Spaces,Footnote 15 but also Cantus and Hommage à Zoltán Kodály (Bird Gardens) for String Orchestra. These pieces incorporate aleatoricism in slightly different ways, but all experiment with interacting levels of musical texture – an aspect that was to remain highly important in Rautavaara's orchestral music. They also draw on the influence of spaces, environments, and objects. Messiaen's modes of limited transposition (especially Mode 2, or the octatonic scale) came to the fore in this period and, in combination with a non-diatonic use of triads, helped Rautavaara begin to organize a new pitch vocabulary, drawing on the complete cycle of twelve tones. He went on to develop this idea further in the opera Thomas by combining multiple tone rows with other pitch collections to form ‘genealogical’ relations between them.Footnote 16 This continuing and dialectic experimentation complicates the ‘neo-Romantic’ label often used for Rautavaara's music around this time, especially as Garden of Spaces might be considered a modernist work in its experimental musical format. Looking beyond these labels makes it possible to see the varied ways in which he builds on modernism while aligning them with other preferences, such as triadic harmony, lyricism, musical symmetry, and extra-musical imagery.

Listening to Cantus today raises questions of modernity and renewability, especially considering its experimental inclusion of an electronic tape recording of birdsong against a live orchestra. This electronic element comprises a particular kind of modernity in the context of the early 1970s. The technique had been similarly used by Alan Hovhaness in his And God Created Great Whales – an orchestral, aleatoric tone poem that features recorded whale song arranged by the composer. Following the advance of digital recording technology, it is unsurprising that this electronic component could sound dated. One review from a Rautavaara tribute concert in 2017 highlights how the mixture of tape recording and live orchestra was once fashionable but felt dated today, and that at one point ‘the caws from the tape came across as unintentionally humorous’.Footnote 17 The question of whether this experimentation actually comprises a ‘gimmick’ is one that might damage the integrity of the piece.

Cantus is caught in a confusing time within Rautavaara's relationship with modernism. The tape recording adds to a wider exploration of the relationship between stasis (recalling landscape) and motion (recalling objects within that landscape) and therefore must also be considered outside its more obvious novelty value. Furthermore, just as he challenges any imposed idea of progressive modernism, Cantus draws attention to the way that nature, with associated ideas of renewability, can challenge the unidirectional view of technological and scientific progress. The reassessed artistic principles behind Cantus therefore invite an ecocritical perspective, as part of its progressiveness and success is found in the way it leads audiences towards environmental awareness, potentially across various geographies. Samuli Tiikkaja describes how Rautavaara was originally commissioned to write a cantata for the University of Oulu and that, in failing to find an enduring text to his liking, he made the decision to include the recorded birdsong from the region, thereby giving the work a universal character rather than a local one.Footnote 18 The rise of ecomusicology, which Aaron S. Allen defines broadly as ‘the study of music, culture and nature in all the complexities of those terms’Footnote 19 makes it more necessary not to overlook the importance of an ecological dimension to the creative aims of this piece, especially in the ways in which it explores the overlaps between musical and natural sounds.

Accessibility and wide appeal

In his overview of Rautavaara's orchestral music, Frank J. Oteri describes Cantus as ‘an instant crowd pleaser reminiscent of Górecki's famous Symphony No. 3 which was written four years later’.Footnote 20 These two composers are frequently compared,Footnote 21 although little unites them stylistically apart from their considerable international success and their return to a broadly tonal sound world. The popularity and wide appeal of Cantus lies in several aspects. First, the outward resemblance to tonal, or modal, music through its consistent use of triads and conjunct melodic motion brings a sense of familiarity. Second, as an example of musique concrète, the over-layered sound of recorded birdsong, recorded by Rautavaara in the arctic regions of northern Finland, connects music with nature in a concrete way, thereby appealing to a wider audience.Footnote 22 Third, this combination of recorded birdsong and live orchestra provides a degree of novelty, even today, making the piece memorable in the context of late twentieth-century orchestral music.Footnote 23 As will be discussed in the following section, the piece is also easily connected to an exotic idea of Finnish wildlife and landscape. Furthermore, each movement of the piece has a clear formal articulation and is monothematic, inviting metaphorical associations of organic growth that align with its subject matter. As Lauri Otonkoski observes, it avoids internal dissension – musical sections are not presented to be in conflict with each other – or ‘hidden structures’, and has a straightforward construction of themes.Footnote 24 Such transparency in the formal structure, on both larger and smaller scales, contributes to the accessibility of this piece.

For the reasons already outlined, Cantus has been used in wider musical contexts. It has caught the musical imaginations of jazz musicians including the Michael Wollny Trio,Footnote 25 Felix Römer,Footnote 26 and Aki Rissanen.Footnote 27 The harmonic organization of the piece, transforming constantly by moving through non-diatonic triads that are typically approached by step, provides an effective impetus for improvisation, allowing these musicians to expand on particular harmonic gestures or figurations. The fact that Cantus was composed at the piano,Footnote 28 meaning these harmonic progressions fit comfortably in the player's hands, has undoubtedly contributed to this dissemination. Furthermore, these connections with jazz demonstrate how the piece crosses a stylistic middle ground in contemporary music.

The wide appeal of Cantus is also reflected in the inclusion of the third movement ‘Swans Migrating’ in the 2012 experimental romantic drama film To the Wonder.Footnote 29 The film music associations of Cantus, which Otonkoski also observes,Footnote 30 can be explained by its tonal-like qualities and the visual connection to landscape. Instead of an arctic, Finnish environment, however, the film features photography of the dry, expansive fields of mid-America, further emphasizing the connection between landscape and memory as a form of escapism. Considering the choice of this music for the soundtrack and issues of cultural translation, it is useful to highlight that the period between 1880 and the beginning of the First World War saw mass emigration of Finns to America, settling in areas such as the Mid-West, where they had a pronounced cultural influenceFootnote 31 and whose presence led to subsequent generations of Finnish-Americans, many of whom adapted to American culture.Footnote 32 The musical evocation of landscape in Cantus offers transferability for this new setting and may connect with ideological landscape images. The imagery of American geography in the film is suggestive of visual tropes that Annie R. Specht and Tracy Rutherford describe as the idealized ‘pastoral fantasy’ of agrarian landscapes in America, the symbolism of which, they argue, ‘constitutes a typology of visual language related to traditional values’, and that the repetition of these tropes ‘has, over time cemented them in American cultural memory’.Footnote 33 This transference of landscape also draws on the ability for music to evoke wide open spaces that goes above specific locations. In analysing the music of the rock band Big Country, for example, Allan F. Moore observes a characteristic experience of wide open space ‘in the difference in perceived motion between events in the near and the far distance, the difference between these conveying the sense of space’.Footnote 34 Moore's analysis of the juxtaposition of ‘intricate surface movement’ and ‘minimal harmonic movement’ as a suggestion of space aligns with the superimposition of levels of musical activity in Cantus, the inner workings of which will be discussed later.

Perhaps the principal motivation for the use of Rautavaara's score in To the Wonder is found in its broader reputation as accessible contemporary music. The soundtrack draws on a variety of pre-existing classical pieces and the inclusion of music by Rautavaara, Górecki and Pärt illustrates their wider perception as ‘tonal’ composers and reflects a general tendency for these individuals to be grouped together, even though the minimalist associations are inappropriate in Rautavaara's case. Jeremi Szaniawski's description of director Terrence Malick's approach to incorporating existing pieces illustrates the connections made between these composers in public consciousness: ‘Malick's cuts come from the more tonal, accessible end of contemporary classical music. Arvo Pärt, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Henryk Górecki and John Tavener all tend toward recognizable harmonies and a pseudo-sacral meditativeness.’Footnote 35 Within the film, Cantus takes on a particular function, becoming further removed from its original context. A scene between the characters Neil and Jane features the quasi-chromatic, static opening to ‘Swans Migrating’ to emphasize narrative tension, while the following modal, melodic, and triadic passage corresponds with a more romantic flashback. The manipulation of these contrasting textures is at odds with the way they blend together as part of one unified movement.

Nature, nostalgia, and the question of exoticism

A significant aspect of the international success of Cantus is its reception as a ‘Finnish’ piece, which leads to the notion of national exoticism, where tropes and images of Finnish culture or geography can become selectively emphasized to create a somewhat idealized vision of reality. In the wider dissemination of this work, these features can also be subsumed under a broader, exoticized ‘Nordic’ label. Philip V. Bohlman's work on Nordic popular music introduces a framework of musical ‘Borealism’ – a way of understanding an exoticized view of the North that builds on Edward Said's theory of Orientalism.Footnote 36 Contextualizing Borealism within the modernity of eighteenth-century European Enlightenment, Bohlman states: ‘It is … in the rise of Borealism that Europe's foundational mythical pasts were sutured together to draw them from the peripheries and forge a future history that would become as modern as it was European. Borealism became modern through the discovery of the self in the otherness of the North.’Footnote 37 The term ‘Borealism’ raises important questions concerning which regions and cultures in the northern parts of the globe are to be included under this label. Hans Weisethaunet also argues that Bohlman's presentation of a dichotomy between the Nordic and Europe ‘risks simplifying the region's geopolitical agencies and realities, whereby the North reappears in the light of the “enlightened” Europe; that is, somewhat anachronistically’.Footnote 38 But Borealism nevertheless provides a reference point for a consideration of, for example, notions of the arctic ‘other’ in determining the complicated interactions between Rautavaara's cultural, geographical, and musical experiences.

As it is easy for images of landscape or ‘Finnishness’ to be selectively emphasized or even distorted, it can become difficult to see Cantus as stylistically significant. Korhonen's description of it focuses on the way that ‘Neoromantic harmonies are enriched by a bird song from a tape’.Footnote 39 Meanwhile, Björn Heile observes a ‘self-exoticism’ behind Rautavaara's international appealFootnote 40 and compares the ‘more traditional and nationalist’ Rautavaara with his modernist countryman and mentor Erik Bergman.Footnote 41 Heile does not refer to Cantus in particular, but given its international success, it is likely that he had this piece in mind. It is true that Rautavaara has benefitted from the saleability of Cantus, as well as his other internationally popular piece, Symphony No. 7 (‘Angel of Light’), and other large commissions might not have come to pass without this success. Indeed, the piece made a significant impression on Vladimir Ashkenazy and ultimately led him to commission Rautavaara's Third Piano Concerto (‘The Gift of Dreams’).Footnote 42 At the same time, Rautavaara is not personally responsible for any over-idealized Nordic elements and, as Otonkoski describes, he was genuinely surprized by the popularity of the piece.Footnote 43 Nonetheless, images of Nordic or Finnish nature contribute significantly to its compositional impetus. Not only was Cantus composed for the inaugural doctoral degree ceremony at the ‘Arctic’ University of Oulu, which ties the premiere and the locations of the recorded birdsong closely together, Rautavaara observes that there is a ‘Nordic atmosphere’.Footnote 44 While this concept can be difficult to articulate, it is possible to unpack some of its characteristics and the influence of the natural environment and associated moods on the music.

Finnish nature seems to have become more important after Rautavaara's time spent abroad – his compositional apprenticeships had taken him to New York (1955), as well as Cologne and Ascona (1957–8). In the 1997 documentary The Gift of Dreams, he discusses how his perceptions of his home country as ‘medium-sized’ (referring to woods, lakes, and other roadside landmarks in the Finnish countryside) changed: ‘I was much more taken with the Alps in Switzerland, or the Atlantic Ocean. Then, in my later years, the Finnish nature has become more and more important. From Finnish nature I got my birds in the Cantus Arcticus composition which is probably the most played work of mine.’Footnote 45 It is significant that this renewed interest in the natural environment of his home country came at a period of stylistic change for Rautavaara. Returning home and beginning to synthesize his various experiences abroad also seems to have completed a circle in his development both as a person and as a composer. When asked about how the Finnish landscape had touched his musical senses, he responded: ‘I don't think that even a most urbanized person born in Finland can avoid being touched by the Finnish landscape – especially by immense woods and swamps and bogs in the North, where I spent many childhood summers.’Footnote 46 Rautavaara also had a personal connection to the Oulu region of Finland, from which his mother came, and was familiar with the nature reserve at Liminka Bay.Footnote 47 As Cantus depicts these regions of Finland, and Rautavaara himself recorded their soundscapes, it demonstrates an individual and subjective view of Finnish nature. But any musical engagement with nature is also connected with culture. Addressing the issue of Nordic musical exoticism in relation to late twentieth-century Nordic musical contexts, Hans Weisethaunet resists the notion that the ‘Nordic’ first and foremost derives from nature, arguing that, in the North, there is culture and not nature alone.Footnote 48 Such a balance goes to the core of an understanding of the elusive ‘Nordic atmosphere’ in Cantus.

The notion of nostalgia also plays a role in the individual and cultural-collective engagements with nature in this piece and is a concept that exists on both individual and collective levels. According to Svetlana Boym, nostalgia is ‘a superimposition of two images – of home and abroad, of past and present, of dream and everyday life. The moment we try to force it into a single image, it breaks the frame or burns the surface’.Footnote 49 This duality or ‘break’ is reminiscent of the way Cantus at once looks back – to Finland (after study abroad), and to tonality (after Rautavaara's complete rejection of it) – and looks forward to achieve something new. In this way, nostalgia overlaps with exoticism if it involves an appealing or ‘other’ image relating to the past. A collective sense of Finnish nostalgia is evident through the evocation of the marsh regions of northern Finland and the inclusion of Finnish wildlife. A congratulatory letter from the Finnish president Urho Kekkonen to Rautavaara expresses his admiration for the piece, which brought back his own memories of the Kainuu wilderness.Footnote 50 A cultural connection to the heroic symbolism of Finnish nature was also evident when the second movement of Cantus, ‘Melancholy’, was performed in 2017 for the National Finland 100 Festival, which marked the centenary of Finnish independence. That Sibelius's Finlandia was also played in the same concert reinforces the association between particular Finnish works alongside national symbolism, identity, and nostalgia. As an expression of personal nostalgia, Rautavaara's approach to Cantus aligns with Boym's view of this phenomenon as not only retrospective but also prospective, an idea that she combines with the notion of ‘off-modernism’.Footnote 51 This ‘off’ adverb, Boym states, ‘allows us to take a detour from the deterministic narrative of twentieth-century history’.Footnote 52 Such a definition connects to the second understanding of modernism presented at the outset of this article – as an individual way of thinking, rather than a set of technical or stylistic resources gained from exposure to the central European avant-garde, which forms a driving element in Heile's account of modernism in Finland.Footnote 53

The sound of the whooper swan – the national bird of Finland – in the third movement (‘Swans Migrating’) presents a particular aspect of Finnish nature, and also a personal source of inspiration to Rautavaara. To him, swans in flight had a transcendental, mystical quality:

I am fascinated by their mysterious, magic ability to command an element we humans can command only with a great deal of fumes and racket in aeroplanes … The appearance of birds in my works is unintentional, so I suppose they must carry some deeper symbolic meaning for me. Birds are mysterious citizens of two worlds. But swan, like man, is unfortunately bound to an element in which it must suffer, to a being that is dualistic … that is why the fate of birds is reminiscent of the fate of man.Footnote 54

Rautavaara was evidently drawn to and inspired by this natural vision that he saw as removed from the earth-bound domain of humans, and which aligns with other mystical notions behind his ‘Angel’ series.Footnote 55 The preceding quotation also recalls the symbolic associations of swans – melancholy and death. Through its musical and aesthetic connections to the music of Sibelius, the second movement ‘Melancholy’ evokes a particular idea of a Nordic atmosphere. The audible similarity with The Swan of Tuonela has been observed by Reidar Bakke, as well as the shared evocation of a melancholy mood triggered by wildlife,Footnote 56 which in Finnish mythology is closely associated with themes of death and transfiguration. Juha Torvinen and Susanna Välimäki in fact analyse The Swan of Tuonela in a similar way in relation to the depiction of a dark, Nordic landscape. They point out how pedal points and a lack of rhythmic urgency remove a sense of temporality ‘as if there were no linear time but only an eternal, mythical time’.Footnote 57 In this sense, ‘Melancholy’ is perhaps an engagement with Finland's own mythological and musical past, but explored through a different compositional vocabulary. However, Tim Howell's point that The Swan of Tuonela requires attention to compositional technique as much as pictorial imageryFootnote 58 is a reminder that imagery and mythology cannot solely define the music of Sibelius, or indeed any composer.

Another side to this imagery is the life-affirming influence of swans, which was also expressed by Sibelius in relation to his Fifth Symphony: ‘Today at ten to eleven I saw 16 swans. One of my greatest experiences! Lord God, that beauty! They circled over me for a long time. Disappeared into the solar haze like a gleaming, silver ribbon.’Footnote 59 Such displays captured the musical imagination of both composersFootnote 60 and it is significant that they each refer to a sense of mystical awe that informs the musical processes.

In the context of Rautavaara's entire output, Cantus can be viewed alongside other pieces that refer to Finnish nature or culture – two examples would be Pelimannit and Thomas, where the clashes of Finnish culture and nature are at the heart of the subject matter.Footnote 61 Each of these pieces explore Finnish culture differently, but also reflect the way Rautavaara's stylistic evolution moves dialectically, reconciling national ideas alongside the influence of compositional techniques from abroad. While the novelty value of Cantus for many is found in the recorded birdsong, a more abstract realization of this natural phenomenon can be seen on other occasions across Rautavaara's output, usually as woodwind figurations, although usually it is placed in a more absolute setting. This technique is used prominently in such works as the Third and the Fifth Symphonies – Kalevi Aho even refers to it as ‘abstract birdsong’ in his analysis of Symphony No. 5.Footnote 62 On such occasions, these figurations (such as those shown in Examples 1.1 and 1.2Footnote 63) present a static quality that is combined with other textures to create a multilayered orchestral sonority and temporal development. They typically use modes of limited transposition. Cantus extends this textural counterpoint through the use of recorded birdsong and, in this sense, cannot be regarded exclusively as a programmatic piece. Ashkenazy was aware of this subtlety. According to him, while the orchestra felt the piece had programmatic qualities – an explicit example being the imitations of a crane in the muted trombone near the beginning of the first movement – ‘it has an atmosphere that connects it with absolute music’.Footnote 64 This particular technique used by Rautavaara is therefore loosely associated with a bird chorus, but its capacity for textural complexity led to abstract compositional possibilities, even if it also lends itself well to avian depiction, as Cantus attests. But this practice differs from the explicit symbolism of birdcalls in, for example, Beethoven's Sixth Symphony, which William Kumbier highlights as one of a number of ‘charged pictorial elements’.Footnote 65 Neither does Rautavaara emulate Messiaen's meticulous transcriptions of birdsong, although both composers were drawn to the exclusively musical possibilities of figurations that are suggestive of them. As Maria Anna Harley states, the ornithological accuracy in Messiaen's music is ‘less important than the development of a new musical style with the birds’ irregular phrase structures, rich timbres, complex melodic contours and intricate rhythmic patterns in incessant variation’.Footnote 66 Another connection is to be made with Messiaen's ‘almost aleatoric’Footnote 67 technique in the bird chorus of his Saint François d'Assise which, according to Harley, resembles Lutosławski's aleatory techniques.Footnote 68 This connection is significant given the influence of both Messiaen and Lutosławski on Rautavaara's music and that Rautavaara frequently uses ‘birdsong’ figurations within passages of limited aleatoricism.

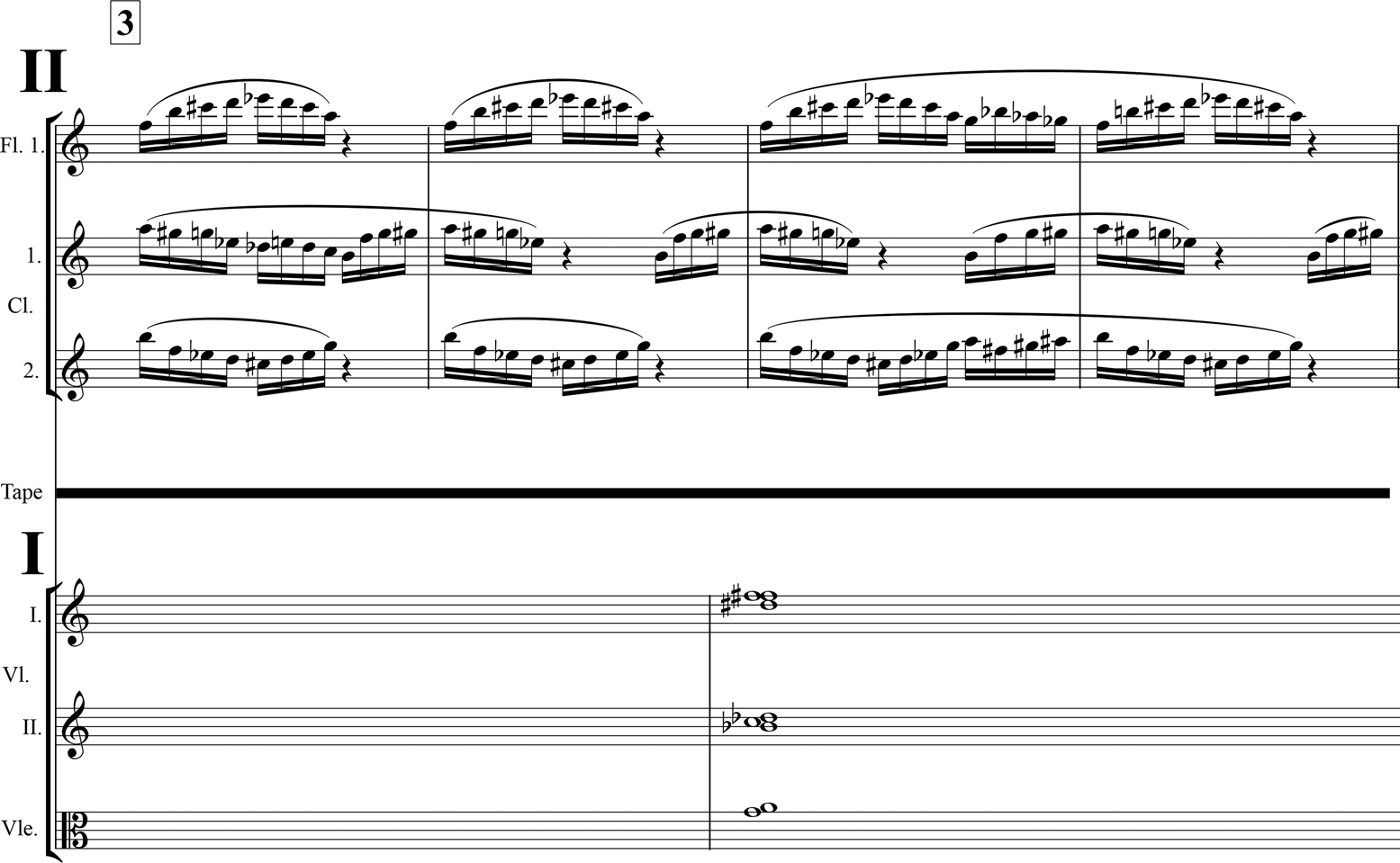

Example 1.1 Cantus Arcticus, ‘Swans Migrating’, Fig. 3.

Example 1.2 Symphony No. 3, Movement 1, bb. 1–3.

Rautavaara's outlook consequently balances the broader development of his musical technique alongside his subjective position on Finnish nature and culture, which have highly relevant roles in this piece. Cantus fits with the cultural value Finland places on valuing and making time for nature, balancing this with urban living within each yearly cycle. The possibility of an environmentalist dimension to Cantus has not been lost on those who have introduced it to wider audiences,Footnote 69 but further distinction should be made between the specific responses to nature outlined previously and the connection to problematic ideas of rugged and comparatively unexplored Nordic regions. It is important to remain critical of such images, especially considering the historic marginalization of Sámi history in relation to national narratives.Footnote 70 Cantus has been included on albums that are packaged with an idealized northerly world in mind, including Ondine's Aurora Borealis: Magic of the Mysterious North, a compilation of Finnish orchestral music performances that ‘match the unique atmosphere experienced when observing the intriguing celestial displays of Northern Lights’.Footnote 71 A repackaged version of this album adds to a vague sense of exoticism that elides Finnish and Nordic images by observing that the Northern Lights have been ‘a dazzling natural phenomenon for thousands of years and have contributed to the image of Finland as a fascinating country full of mystery’.Footnote 72 This call to the wild is also evident in the piece's inclusion on another compilation album by Deutsche Grammophon: Aurora: Music of the Northern Lights.Footnote 73 Apart from the connection with the geographical location, Rautavaara's vision behind the piece has far less to do with the Northern Lights than such packaging would suggest. His references to the springtime setting of the first movementFootnote 74 show arctic Finland in a different light (as it were) to that of the shimmering Aurora Borealis draped over dark winter skies. It is this image, however, that came to mind for English/Australian artist Bruce Munro, who created an exhibition, also called Cantus Arcticus, directly inspired by Rautavaara's piece. According to the description of this exhibition: ‘For Munro, the sounds of arctic birdsong interwoven with Rautavaara's orchestral score created a visual soundscape: shimmering curtains of light suggesting the Aurora Borealis interspersed with the silhouettes of circling birds.’Footnote 75 However, as a visual composer, it is indicative of Rautavaara's approach that his music can inspire these images, be channelled into new directions, and therefore reach a wider group of people. The persistent draw of such Nordic ideas fits well with the promotion of his music, as evidenced by Peter Duncan's description of Cantus within a larger, accessible guide to classical music as a ‘mysterious and exotic sound-world, with the birdcalls emerging and disappearing in the sombre half-light of Rautavaara's orchestral landscapes’.Footnote 76

A broader Nordic exoticism is not limited to the music of Rautavaara. Grimley points out the problematic view of a generic ‘Nordicness’ in relation to Sibelius's music:

For many listeners, Sibelius's Finland is still associated with a particular idea of northernness: an exotic realm of icy waters, somnolent lakes, endless spruce forests, and untouched wilderness. This problematic vision of an idealized Nordic landscape has exerted a powerful influence on Sibelius reception, pointing toward what Peter Davison (alluding to Glenn Gould, an enthusiastic fan of Sibelius's music) has called our ‘idea of north’.Footnote 77

To avoid an equally problematic vision in relation to Rautavaara, it is necessary to be open to the more multifaceted make up of both his compositional intentions and Finland itself, which is distinguishable from a more general ‘Nordic’ landscape. Grimley's assertion that the music of Grieg reveals a ‘fundamental tension in Norwegian nationalism between cosmopolitan, assimilatory and isolationist trends’Footnote 78 aligns closely with the need to examine the inner tensions and complexities of one of Rautavaara's most nationally aware – and internationally successful – pieces.

Landscape, form, and texture

While the recorded birdsong in Cantus Arcticus brings the arctic marshes of Finland to the auditory foreground, there are larger questions concerning the role of landscape in this piece, especially how the musical form and interactions of musical texture can articulate the feeling of being in a particular environment. A sense of participation with the landscape comes across in Rautavaara's description of the opening movement: ‘The first movement, Suo (‘The Marsh’) opens with two solo flutes. They are gradually joined by other wind instruments and the sounds of bog birds in spring. Finally, the strings enter with a broad melody that might be interpreted as the voice and mood of a person walking in the wilds.’Footnote 79 Landscape therefore permeates this piece much more deeply than through an electronic soundscape. Rautavaara's response to a question concerning the importance of Finnish nature had an extra comment that he added in pencil: ‘These landscapes are symphonic.’Footnote 80 Associations between symphonic writing and landscape are also seen in Symphony No. 3, which Rautavaara said responded to a need to make the music move in ‘the rhythm of the land and sea’,Footnote 81 and in the Fifth Symphony, in which, according to Aho, ‘new horizons perpetually open up’.Footnote 82 For Rautavaara, ‘landscape’ was a powerful creative impetus in symphonic composition, often expressed through the manipulation of musical textures and motivic development conveying a sense of size and the sensation of moving through vast spaces. The transformation and development of these musical landscapes features heavily in his Eighth Symphony (‘The Journey’) – in the preface for this work, Rautavaara describes the symphonic form generally as ‘transformations of light and colour’ and the finale of the symphony as ‘flowing onto a broad estuary, the everlasting sea’.Footnote 83 While it is not a symphony, the individual movements of Cantus explore a similar relationship between perceptions of motion and stasis, especially through the manipulation of groups of musical textures. The perception of moving through landscape relies on the combination of static and dynamic textures, a duality in which the recorded birdsong participates. The duality of stasis and motion can be found within the recorded birdsong as a soundscape – a sound environment contained to a region, but within which movement takes place. The interactions between these various states provide the particular dualism for this unusual concerto setting. These metaphorical aspects relate to the notion of ‘journeying’Footnote 84 which, as Tim Howell observes,Footnote 85 is a persistent one in his output. Like many of Rautavaara's pieces,Footnote 86 the opening movement begins with an ‘atmosphere’. The evocative and sensory nature of the melody in ‘The Marsh’ derives from supporting triads played in the lower register of the orchestra that, in combination with birdsong figurations in the woodwind, create depth and a richness of sound. The ascending melodic line creates a blossoming effect, added to by the cumulative orchestration. By the time the full string section enters, this evocation of an arctic spring reaches a peak of intensity and consecutive cluster chords in homophonic motion add to this richness. Such harmonic parallelism is a highly characteristic technique and is often put to expressive use in Rautavaara's music, adding emphasis to linear melodic motions. This technique is also emblematic of the period following his departure from strict serialism – a particularly extreme example is the Piano Concerto with the use of full-arm, white-note cluster chords. In the concerto, the rebellious and dissonant nature of these cluster chords simultaneously bolsters a fresh and sonorous neo-tonal language, demonstrating how Rautavaara tests boundaries of consonance and dissonance. In the same spirit of finding the full potential for compositional techniques, Cantus puts this harmonic parallelism to a different, sensory use.

A particular balance between motion and stasis is evident in the second movement (‘Melancholy’). As the title of the movement suggests, mood and atmosphere are of great significance. The accompanying recorded soundscape is the call of the shore lark, which has been brought down in pitch by two octaves to make it, in Rautavaara's words, a ‘ghost bird’.Footnote 87 Stasis is suggested by this self-contained, short movement and, although it is developmental, overall it presents a kaleidoscopic, spatial view. Additionally, extended pedal points incur an overall static quality. Finally, the layout of the movement, which develops thematically and in volume, is symmetrical in structure. Within this image, however, the dynamic musical parameters offer an expressive emphasis, shown through an increased intensity of volume and orchestration.

That ‘Melancholy’ demonstrates a powerful sensitivity to the natural and cultural images of the arctic Finnish environment is also revealed in the musical evocation of coldness, or an open location, that channels into a larger expression of melancholy. The influence of visual or environmental elements (light and dark/cold and heat) contributes to the broader significance of landscape as a representation of subjective experience, as well as musical responses to elemental size. Coldness can be understood in terms of absence – the absence of heat. In colour, ‘coldness’ can be defined as the absence of those shades that remind us of heat, hence why colours such as blue and green are considered ‘cool’, while brighter colours such as red, orange, and yellow are ‘warm’. In temperament, ‘coldness’ is understood as the absence of visible passion or emotion. Musically, the absence of brass and percussion for the majority of ‘Melancholy’ therefore creates a ‘cold’ atmosphere. Additionally, the opposition between low and high registers creates a hollow quality, explained by the relative absence of ‘warm’ middle and lower registers. The associations of low registers as dark and high registers as bright have been observed in relation to Finnish musicFootnote 88 and this combination presents a cold light source, as the darker string tones contrasts with high, suspended lines in the upper strings. The use of muted strings and the avoidance of expression, both within the score and in recordings of this piece, all add to this atmosphere, alongside the evocation of an isolated and perhaps forbidding location.

Cantus therefore points to a Finnish idea of melancholy – one that brings together the Finnish landscape, culture, and ecology in a complicated blend. It also demonstrates Rautavaara's reconnection with Finland and he was certainly aware of the significance of Finnish myths and the relationship with landscape.Footnote 89 A similarly complex interaction of physical and cultural landscape can be observed in relation to another piece concerned with a cold location – Vaughan Williams's Sinfonia Antartica. The tensions between stasis and dynamic motion in this symphonic setting have been observed by GrimleyFootnote 90 and the description of passages of the symphony by Hugh Ottaway as ‘panoramic’Footnote 91 further illustrates how music can reflect the dualistic relationship between humans and an open environment. Cantus has been compared in reviews to Vaughan Williams's musical style,Footnote 92 and their harmonic and melodic similarities will be discussed in the next section, but a tangible comparison would be the extra-musical inclusion of soundscape within an orchestral setting. The use of a wind machine in Sinfonia Antartica, like Rautavaara's use of recorded birdsong, with its programmatic effect, points more literally to the relationship between music, landscape, and ecology, and connects musical processes and textures to an imagined space. In turn, this fact can help in understanding those less literal structural representations of landscape and human agency in Rautavaara's later orchestral and symphonic works.

The third movement, ‘Swans Migrating’, incorporates aleatory techniques. There are four orchestral groups with exact notation. In combining these groups, Rautavaara makes different textures interact, including those that are static (such as repeating ‘birdsong’ figurations) and those that are more dynamic (such as a melody in parallel harmonies). The overall effect is the fluid motion of one mass that is actually made up of separate parts, resembling birds in flight.Footnote 93 A particular effect comes from inserting a small amount of freedom as to exactly when each group enters – a balance that Rautavaara explored on a number of occasions. Consequently, multiple layers of motion operate at different paces and on different levels to create a complex and expansive orchestral sonority. At the beginning of the movement, groups one and two operate asynchronously, incurring the sense of control in apparent randomness. This remains the case when the broad melody of group 3 enters and, likewise, group 4, which uses the harp and celeste. As the melodic material of group 3 develops, the orchestra becomes more synchronized.

As with ‘Melancholy’, ‘Swans Migrating’ is a more programmatic realization of the various techniques that Rautavaara was experimenting with and attempting to integrate into his larger style. The same organization takes place, albeit on a larger scale, in Garden of Spaces, composed just one year earlier. This technique falls under Rautavaara's ‘textural polyphony’,Footnote 94 where his interest in aleatoric devices opened up new possibilities in the role of textural dialogue and transformation to manipulate the portrayal of static, symmetrical musical landscapes versus dynamic motion and dramatic narrative. The temporal unfolding of spatial musical organizations determines the duality within the musical form between time and space. However, while ‘Swans Migrating’ combines textures and different perceptions of musical time in this way, unlike Garden of Spaces it is ultimately a sense of dynamism that wins through. Rautavaara describes this process: ‘The texture constantly increases in complexity, and the sounds of the migrating swans are multiplied too, until finally the sound is lost in the distance.’Footnote 95 If Garden of Spaces engages with architectural spaces – indeed, the title is taken from an architectural exhibition by Reima PietiläFootnote 96 – Cantus engages with natural space. The two pieces can therefore be viewed as counterparts to each other, echoing the close correspondence between nature and architecture in Finnish culture, as well as the stylistic balance that became increasingly significant in Rautavaara's music.Footnote 97

Tonal renewal

Neo-tonality is a significant element within Rautavaara's individual musical language and is largely responsible for a sound world that is both familiar – which undoubtedly contributes to its wide appeal – and novel. But the tonal-like style of Cantus can be a sticking point in the reception of this piece. It is of course true that Cantus draws upon a familiar harmonic and melodic language and the use of triads, mediant-related harmonies, and modal-like melodies explains comparisons with film music. In one sense, the piece appears to look backwards in comparison to the pitch organization methods of such earlier works as Arabescata, but a fundamental idea within Rautavaara's complicated relationship with modernism is that looking backwards was a prerequisite for moving forwards. He had been forced to reject any linear narrative of modernist musical development on the level of technique and musical materials. The work's resemblance to tonal models logically disassociates it from an idea of artistic significance based solely on the rejection of tonal traits. While Rautavaara did not prevent or obscure these resemblances, his particular perspective and subtle renewal of tonality require closer inspection.

The idea that tonality has been marginalized has been challenged in recent investigations into the ‘flourishing’ of post-war tonality. Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler, and Philip Rupprecht observe in the recent edited volume Tonality Since 1950 how an eclectic group of composers have approached tonality from different angles in the late twentieth century.Footnote 98 Rautavaara is an important case study to bring into this larger attempt to observe complexity and nuance in recent approaches to tonality. The aim in Tonality Since 1950 – to observe continuities in late twentieth century tonal practice, rather than sudden breaksFootnote 99 – provides a useful context in which to identify Rautavaara's own adaptations and continuities in this area, without abandoning the idea of compositional continuity and establishing his own style. But his return to tonality was also shaped by experiences of serialism. As such, Rautavaara embodies what Wörner, Scheideler and Rupprecht describe as the ‘special historical complexity facing composers working since 1950’.Footnote 100 He both departed from the tonal past but reconnected with it, while reflecting critically on what he wanted to continue from his atonal modernist experiences. This convoluted continuity is characterized not by a unidirectional flow of development but by exploration, reassessment, and periodic decision making. Beneath the outward simplicity of the neo-tonality in Cantus is a complex organization that facilitates this musical language.

After the creative crisis centred on serialism, the reintroduction of triadic harmony and modes of limited transposition (especially the octatonic scale and Mode 6, alternating pairs of whole tones and semitones) was a reaction against the constraints of overly methodical prior structures that led Rautavaara to conclude that he ‘had to keep harmony’.Footnote 101 This music from the late 1960s has been described as the ‘free tonal’ period,Footnote 102 a term that needs unpacking further as he did not simply abandon theoretical pitch structures during these years. What ‘free tonality’ really means is the non-conformity to the expectations of diatonic, functional tonality or modality, and a search for a new set of guidelines or organizing system that affords greater flexibility. Symmetry, as expressed holistically through the twelve tones as a democratic resource, featured heavily in this critical reappraisal of both tonality and serialism. While this approach does not continue the prior theoretical organizations of serial music, it maintains the principle of having a larger pitch system in the background, while offering considerable flexibility.Footnote 103 Cantus is one of the orchestral works that goes a long way in synthesizing pitch sub-collections, achieving great harmonic and melodic variety within one organized, neo-tonal network. This wide-reaching perspective on pitch differs slightly, therefore, to the concentrated use of the octatonic scale in Garden of Spaces.

The period between the late 1960s and early 1980s consequently provided a productive middle ground for Rautavaara's tonal renewal. In the 1990s, he stated that the twelve tempered tones were the vocabulary of the twentieth century and that it was a question of organizing it,Footnote 104 and he further remarked that he sought to seek a synthesis between the modern and the more or less tonal harmony.Footnote 105 He also compared pitch organization to the Jungian notion of ‘Mandala’ as an ‘antidote against chaos’.Footnote 106 Rautavaara expressed these ideas, after he began to use twelve-tone rows again, blending them with symmetrical modes and tonal-sounding harmonies and melodies. This particular synthesis of pitch systems began in the opera Thomas.Footnote 107 However, Cantus demonstrates that, during the period from the late 60s until the mid-80s, he was exploring the same idea of drawing on the twelve-tone vocabulary, but using slightly less predetermined organizational methods.

While the twentieth-century compositional developments made it clear for Rautavaara that the broader universe of the twelve-tone set still had a part to play, the triad, with its natural resonances, also had a place in contemporary music. In Cantus, tertian harmony also helps express the depth, space, and resonance of a natural environment. It is also significant that Rautavaara composed at the piano, as stated earlier, and the physical spacing of the keyboard links with the constantly evolving harmonic landscapes in the piece between non-diatonic triads within a focused region of the keyboard. The physical layout of the piano also makes it possible to see the structure behind these harmonic progressions, as freer (in comparison to functional diatonicism) stepwise motion in the melody that ‘resolves’ into new triads, utilizing a broader tertian system. While harmonic and melodic motions are able to occupy or suggest harmonic centricity, they are in no way limited by it. If Cantus has a ‘centre’, it is to be found in the cyclical symmetries within its musical materials.

Rautavaara's critical reassertion of those enduring aspects of tonality aligns him with a broader issue that runs throughout the twentieth century, one that has been indicative of a larger critical relationship with serialism. Broadly, this is what George Perle and other writers have referred to as twelve-tone tonalityFootnote 108 and interval cycles. These organizations, which have been identified in the music of such composers as Bartók, Stravinsky, Debussy, Messiaen, and Perle himself allow, first, an organization of pitch that operates outside functional, diatonic tonality and, second, a foregrounded sense of equality and symmetry in harmonic and melodic organization.Footnote 109 Rautavaara's orchestral music incorporates various cyclical arrangements of notes, combining them and evolving them to provide harmonic diversity and dynamism, making the horizontal and vertical dimensions of music work in a different way. Samuli Tiikkaja also observes symmetry and circularity in Rautavaara's music and applies a theoretical model, the ‘Harmonic Circle’ – a triadic cycle of alternating major and minor thirds – to Rautavaara's music.Footnote 110 Despite appearing to be one of his most tonally traditional pieces, Cantus develops different kaleidoscopic organizations and superimpositions of cyclical intervallic structures in a way that looks to later pieces, notably Symphony No. 5, but which also helps give this work its own character. Such combinations of pitch cycles work in tandem with the textual and formal processes discussed earlier.

The first movement, ‘The Marsh’, reveals a panoramic organization of harmony and melody. The opening uses a focused theme that repeats but continually opens out into new harmonic vistas and this process is driven by a larger, governing system. The linear orientation of tonality – moving from and towards keys – is replaced by a continually transforming harmonic and melodic process. However, certain tonal aspects, such as modal shifting, are renewed. A sense of complexity and circularity comes from the simultaneous use of different interval cycles, including synthetic modes and tertian harmony. The influence of landscape is significant at this level of melodic and harmonic processes – the repeating thematic material, which brings unity, is harmonized slightly differently each time, creating the sense that this musical environment is viewed from different angles as new horizons open up.

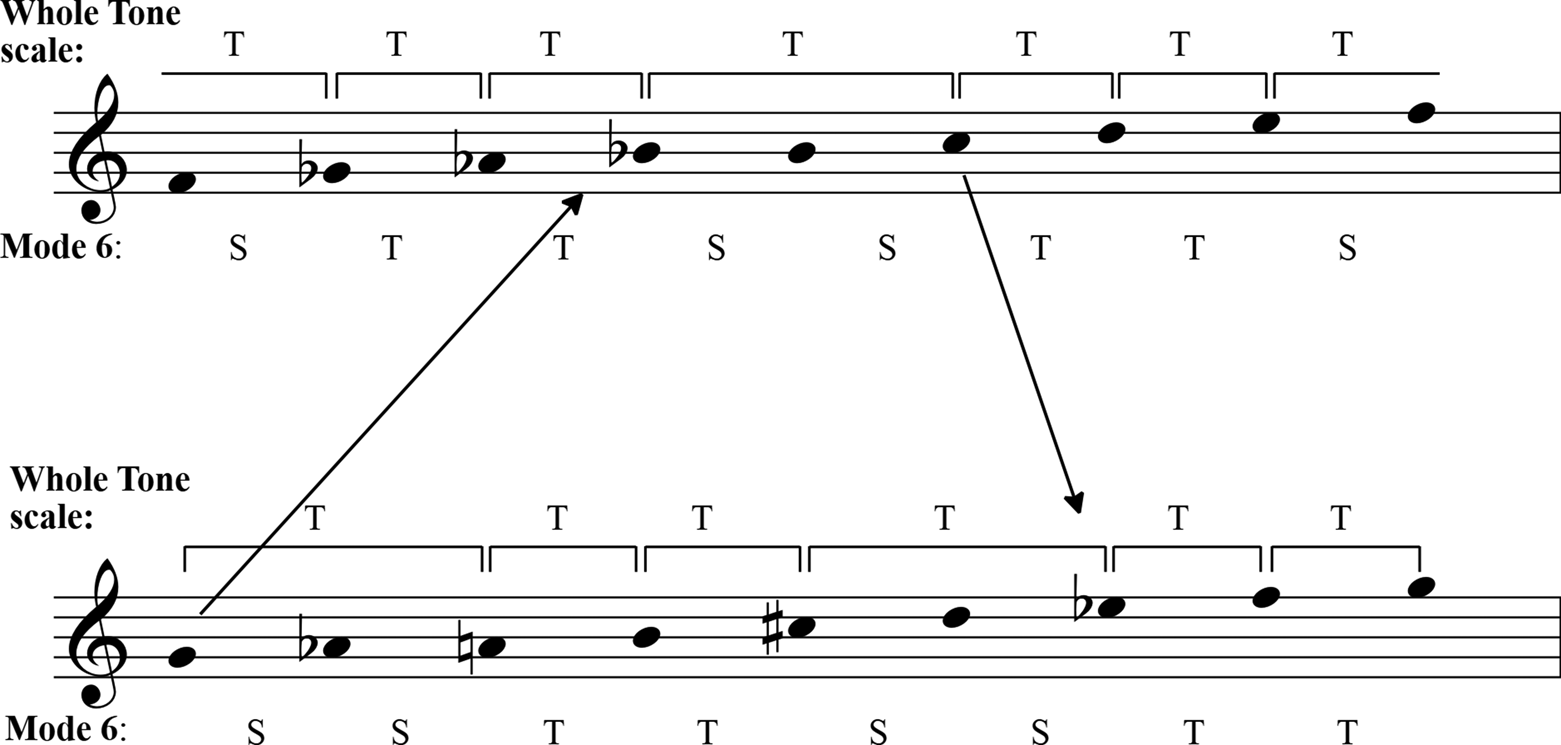

The opening dialogue between the two flutes in ‘The Marsh’ (Example 2.1) uses a varied combination of whole tones and semitones, suggestive of Mode 6, as well as the whole tone, chromatic, and diatonic scales. The score includes the inscription ‘Think of autumn and of Tchaikovsky’ – a nod, Bakke says, to notions of seasonal melancholy expressed in music.Footnote 111 Bakke observes that Rautavaara may have had Tchaikovsky's piano piece ‘October’ in mind.Footnote 112 The tonally neutral quality of the opening melody serves to emphasize this atmosphere. These lines orientate around the notes F and B, which form polarized centre points for flurrying, bird-like melodic lines. As these centre points are a tritone apart, they present a symmetrical and static backdrop, as the melodic lines always return to these two notes.

As Example 2.2 shows, this opening passage is loosely structured around two transpositions of Mode 6. Contained within each of these collections is also a version of the whole tone scale. This pair of transpositions organizes the twelve tones symmetrically – consequently, every note from the chromatic set is heard by the end of bar 3 in Example 2.1. The arrows in Example 2.2 demonstrate how Rautavaara shifts between these modes through the interval of a minor third. Such symmetry allows the focused pitch region (less than an octave over bars 1 and 2) to be reconfigured when ascending and descending with these modal shifts – a process that is suggestive of the inversional symmetry between landscape and water. These modes also have four notes in common that outline a diminished chord (a♭1, b1, d2, and f2), further demonstrating the structural symmetry of tritones and interval cycles. These opening bars therefore set up a synthesis that occurs throughout the piece, where Rautavaara combines his modernist fascination with symmetrical pitch organization on multiple levels alongside a new perspective on tonality and the evocation of Finnish landscape and nature.

Example 2.1 ‘The Marsh’, bb. 1–12.

Example 2.2 Two transpositions of Mode 6 as a melodic foundation for bb. 1–12.

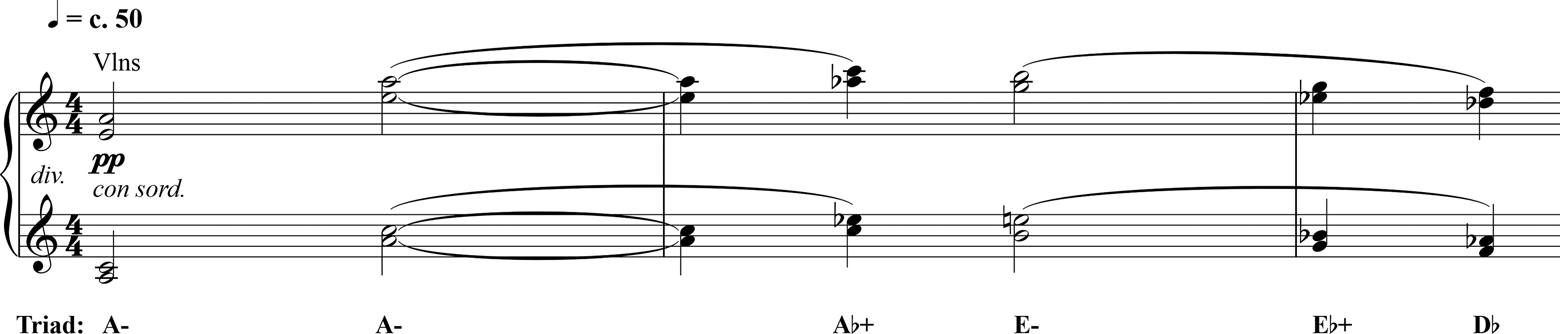

Another highly characteristic part of Rautavaara's technique is the use of slowly evolving, non-diatonic triadic progression. This technique forms the basis of the second movement, ‘Melancholy’ (Example 3.1). As Example 3.2 demonstrates, consecutive triads are often chromatically related (see the transformationFootnote 113 between A minor and A♭ major in Examples 3.1 and 3.2), while others are approached by whole tones or via chromatic mediant relations. This approach centres on transformations between triads, enabling shifts between chords using notes from opposite sides of the circle of fifths. This harmonic language might also explain the comparisons with the music of Vaughan Williams,Footnote 114 although these two composers approach this technique via their own paths. Chromatic mediant relations are a hallmark of Vaughan Williams's style, and both composers used the octatonic scale and other symmetrical pitch collections to achieve continuity over non-diatonic harmonic shifts.Footnote 115 Rautavaara's practice here could also be related broadly to Schoenberg's term ‘floating tonality’,Footnote 116 where key boundaries are tested to create a suspended tonal effect. However, his starting point in the late twentieth century was to approach tonality from outside, rather than pushing outwards from within, and the grammar of his neo-tonality is based outside of seven-note diatonic or modal collections.

Example 3.1 ‘Melancholy’, bb. 1–3.

Example 3.2 Triadic progression, ‘Melancholy’, bb. 1–3.

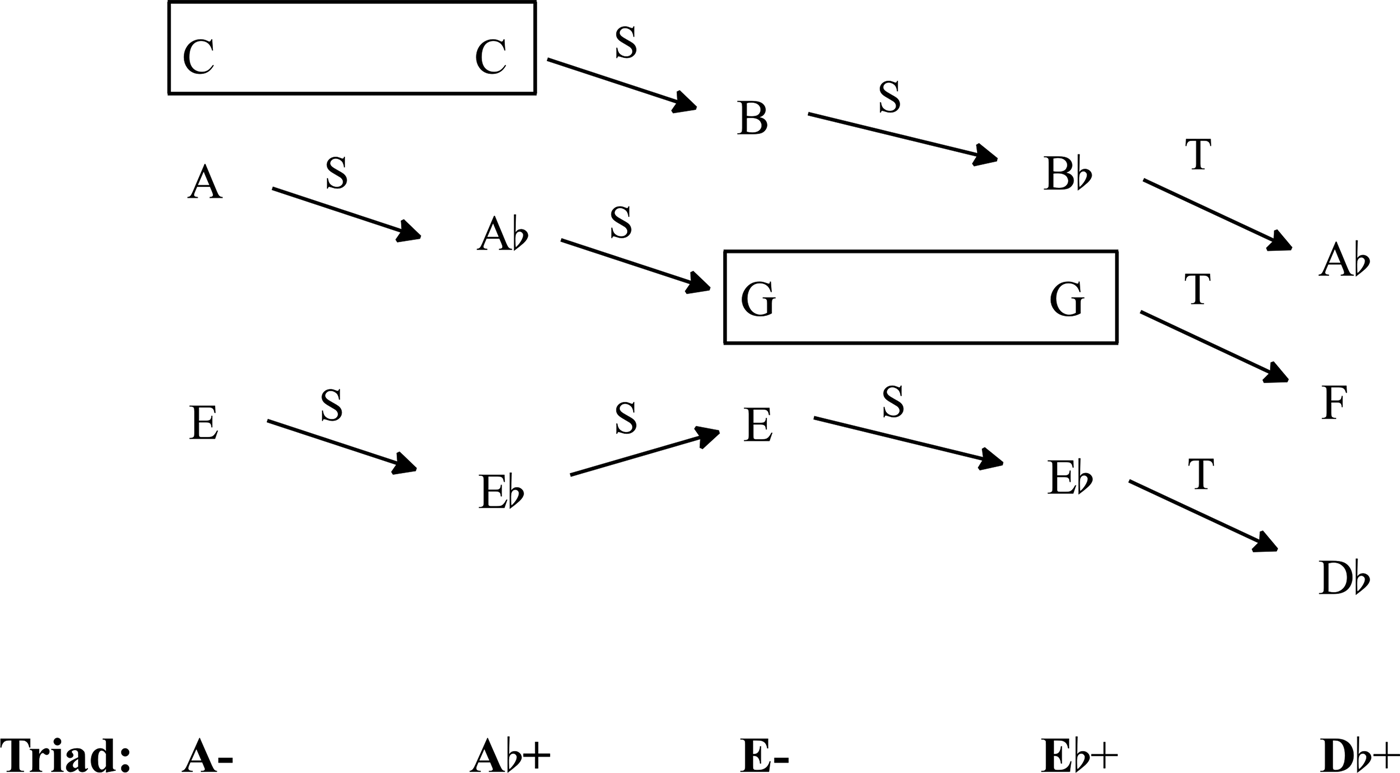

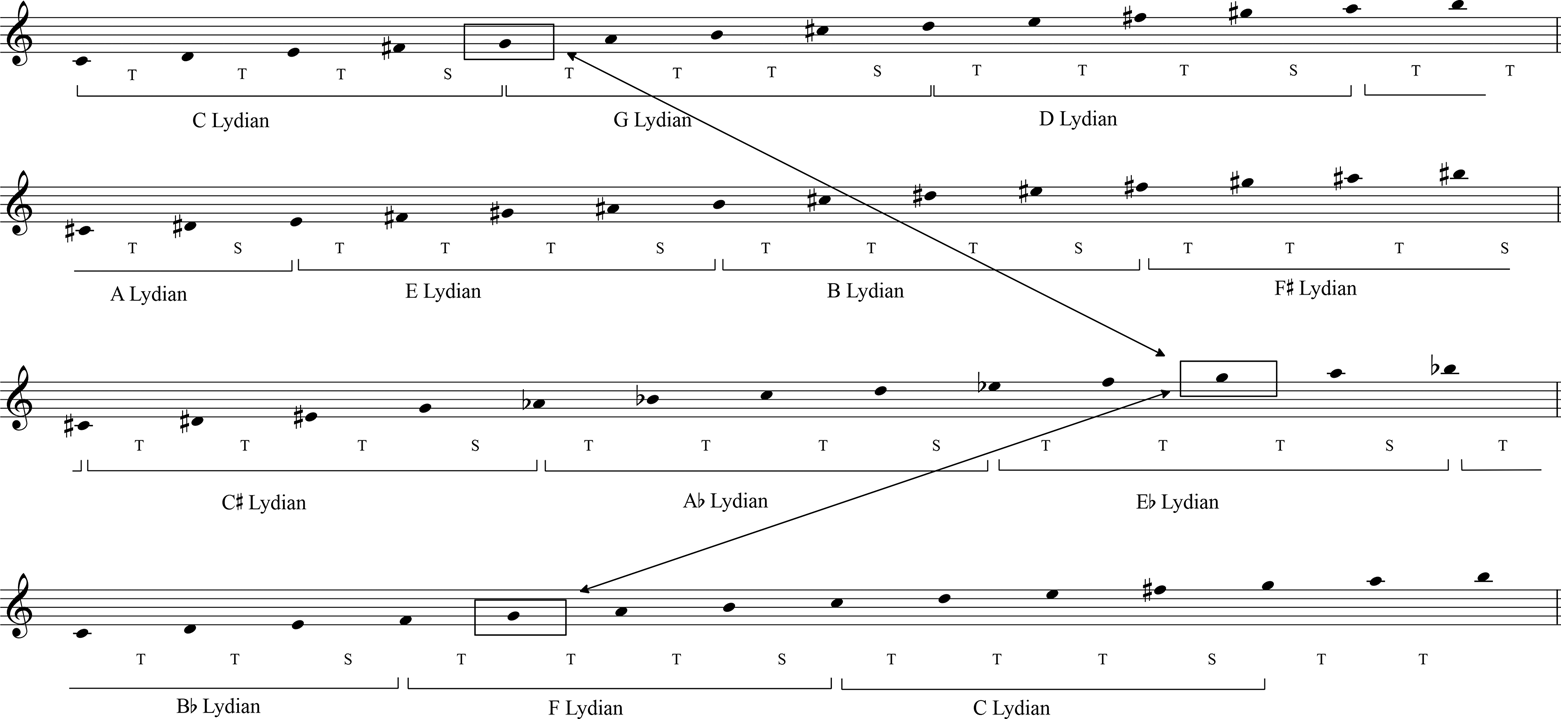

The third movement, ‘Swans Migrating’ is an effective case study in Rautavaara's tonal renewal. As in ‘The Marsh’, a single melody repeats, transposed each time and altered through different orchestration and development through countermelodies. Mikko Heiniö observes the use of modal melodies in Cantus,Footnote 117 and ‘Swans Migrating’ certainly has a Lydian flavour, although it is uncontained to this mode and moves efficiently between different harmonic areas to achieve non-diatonic harmonic contrast. The interval set of three tones and one semitone (T–T–T–S) occurs consistently in this movement, especially as a melodic-motivic impulse, and plays a significant part in the shifting between quasi-diatonic, modal-sounding areas that nevertheless operates beyond any mode. This intervallic configuration outlines the first five notes of the Lydian mode and Example 4.1 maps out a cyclical pitch network based on repetitions of it. This large cycle thus forms a melodic expansion of the circle of fifths (this arrangement will be called the ‘Lydian Cycle’). Like the circle of fifths, any seven-note segment of consecutive notes outlines a diatonic set.

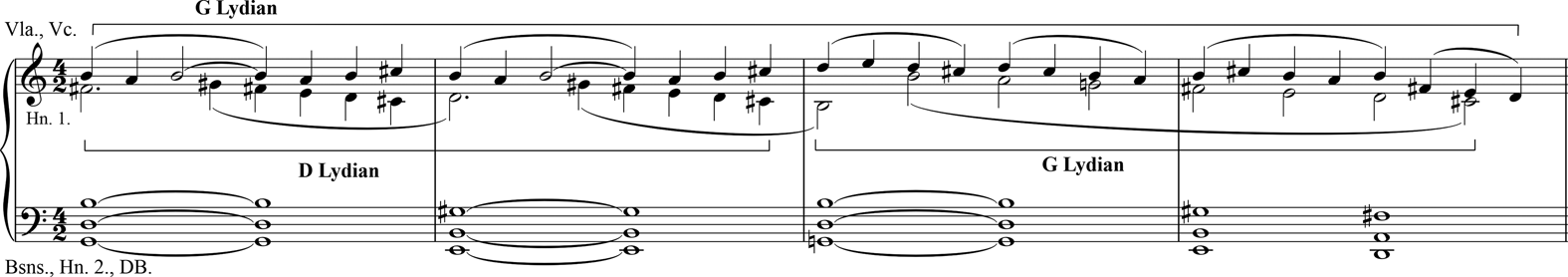

Example 4.1 Shifting function of the note G on the ‘Lydian Cycle’, ‘Swans Migrating’, Fig. 6.

Example 4.2 shows how the horizontal and the vertical work together, working beyond harmony alone. When the melody first enters at Figure 6, the renewal of such tonal elements as ‘function’, ‘voice leading’, and ‘common tones’ becomes clear. These qualities take on a new role within a restructured neo-tonal system. At Figure 6, the harmony moves between E♭ major and C major triads. As shown in Example 4.1, the ‘function’ of the note G in the passage from Figure 6 (Example 4.2) switches from the third scale degree of E♭ Lydian to the fifth scale degree of the C major chord in C major/F Lydian. This transition is achieved through renewed means of voice leading. As highlighted through the boxed notes in Example 4.2, a stepwise melodic motion from the note a to g brings directional energy to this harmonic shift. Meanwhile, the use of pivot notes facilitates these modal shifts and provides the logical basis for harmonic change. This harmonic motion between E♭ major and C major could be described in neo-Riemannian terms as a ‘Relative-Parallel’ transformation, but the integral role of melody aligns with Richard Cohn's observation that such harmonic operations align naturally with principles of ‘parsimonious’ voice leading.Footnote 118 Throughout this movement, however, Rautavaara expands the notion of efficient voice leading beyond ‘extended’ tonality to find smooth connections between pitch organizations that share common tones. This is not a modulation, but a method of harmonic progression – a subtle but important distinction that reveals the theoretical premise of one twelve-note network.

Example 4.2 Harmonic shifts and voice leading in ‘Swans Migrating’, Fig. 6.

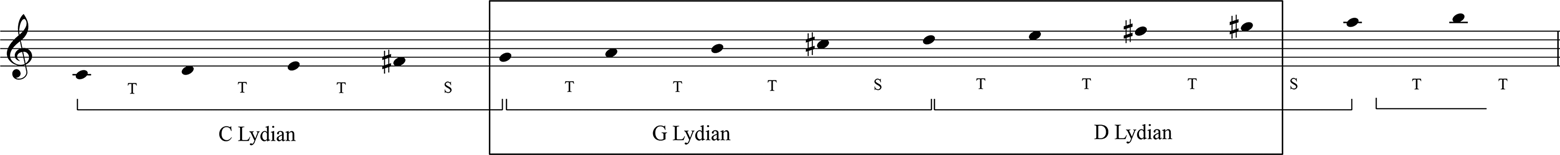

As ‘Swans Migrating’ develops, Rautavaara uses more extended eight- or nine-note regions, shown in Examples 5.1 and 5.2. He therefore combines transpositions of the Lydian T–T–T–S interval pattern based on g1 and d1 (see the upper stave in Example 5.1).Footnote 119 The resultant non-diatonic clash between g♯1 and G in this example creates a particular sound quality, one that is generated from the systematic intervallic organization that creates a kind of super-modality. Although a highly detailed feature, it illustrates how Rautavaara's starting point for harmonic and melodic organization is to organize the twelve tones into quasi-modal, and quasi-diatonic, segments that can overlap. Recognizing this distinction, where Rautavaara operates outside of tonality, without denying it, helps determine why this musical language is both familiar and novel. Evidence of this larger perspective on pitch can be traced throughout the piece, even in the most diatonic-sounding moments.

Example 5.1 Overlapping Lydian segments between upper and lower lines in ‘Swans Migrating’, five bars after Fig. 7.

Example 5.2 Consecutive Lydian segments shown on the ‘Lydian Cycle’.

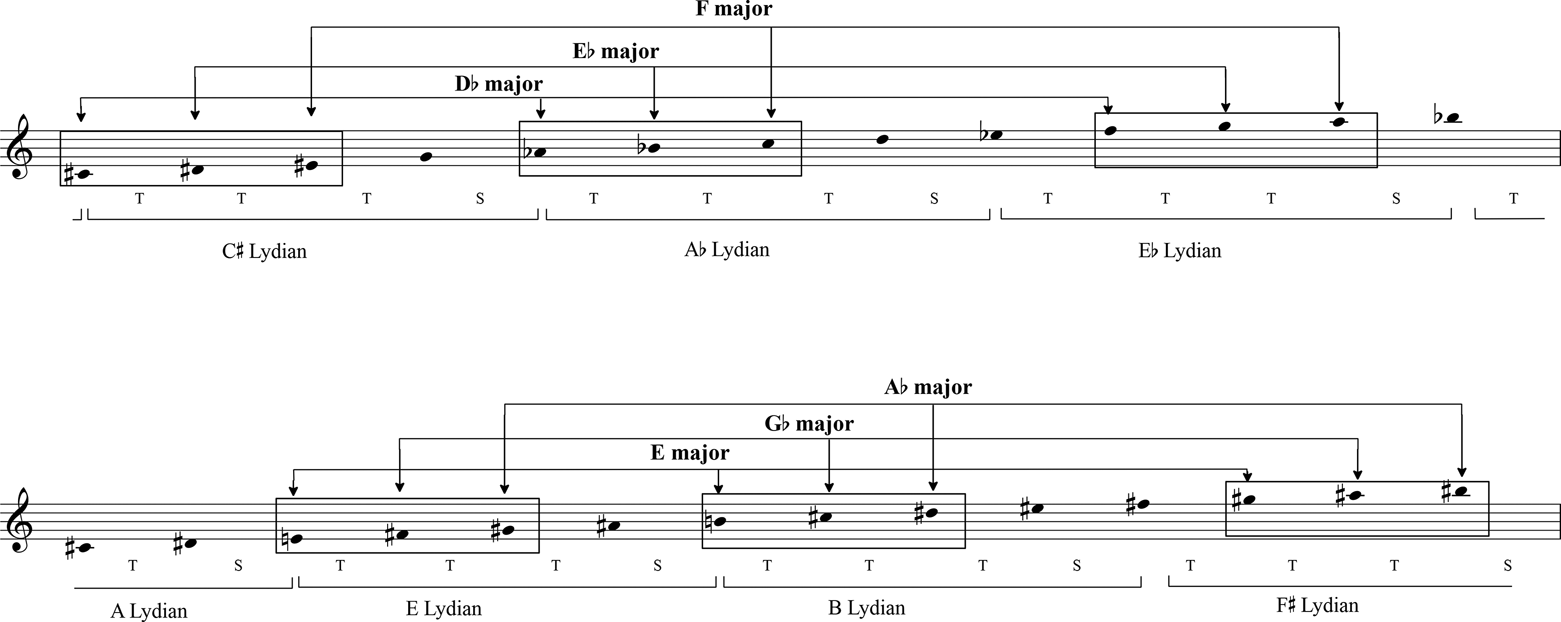

At the end of the piece (Example 6.1), this motif expands into a much broader pitch organization, befitting the extra-musical associations of swans in flight. The melody now moves in parallel triadic harmonies (see horns and trumpets in the first bar of Example 6.1) centred on the chord E♭ in the first bar, before this pattern transposes up a minor third in the next bar, centred on G♭. These two sets of parallel chords are shown on two segments of the Lydian Cycle in Example 6.2 (here, notes belonging to triads are shown with arrows, while boxes show stepwise motion). The octatonic figuration in the oboe in Example 6.1 forms a connecting bridge between these two sides of the cycle, further reinforcing the larger sense of symmetry.

Example 6.1 ‘Swans Migrating’, Fig. 11.

Example 6.2 Whole-tone motions between triads on the ‘Lydian Cycle’, ‘Swans Migrating’, Fig. 11.

Between exoticism and modernism

Cantus Arcticus is a complicated piece that is simultaneously widely accessible and popular, an evocative depiction of Finnish nature, and part of a progressive musical style that builds on a personal relationship with modernism. While the work has formative qualities in the context of Rautavaara's stylistic evolution, it transcends boundaries of musical modernism, place, and accessibility and requires multi-layered examination. To consider only one of these outcomes is to risk overemphasizing, or even distorting, it and thereby undervaluing another. This danger has been encountered in relation to Rautavaara's music – his return to tonality in the late twentieth century was highlighted by his former pupil Esa-Pekka Salonen as something that, in Salonen's student years as a young modernist, could feel like a ‘sellout’ – a view that he now reflects on differently, recognizing Rautavaara's advocacy for a nuanced position in relation to imposed modernist-stylistic ideals.Footnote 120 Of course, the argument for such a balanced perspective works both ways: the advances in musical technique alone find more subtlety in later works such as Thomas and those symphonies that are suggestive of landscape, such as the Fifth and Eighth, and the earlier Third. But, in its synthesis, integration of forces, unity, and breadth of expression, Cantus foreshadows his mature works. This fact makes it more necessary to reconsider the, by now, settled periodization of this composer's output. Rather than highlighting the ways in which Cantus is different or ‘postmodern’, as Heiniö believes it to be,Footnote 121 it is productive to observe the interactions and connections between this and other orchestral works in Rautavaara's extensive output. Its more explicit explorations of the relationship between music, nature, and landscape furthermore indicate a highly significant step in the continued development of his musical personality – the searching for which remained consistent during a time of technical reassessment and experimentation. Combinations of local, international, and spiritual dimensions take this music beyond the parochial, without abandoning it. Consequently, the role of the piece in his stylistic development, especially in negotiating the difficult, personal, and progressive road beyond modernism, is greater than previously thought.

The musical language of the work is also highly representative of Rautavaara's lasting voice, resulting in a renewed tonal solution that raises larger questions concerning how tonality will continue to adapt and change in contemporary music today, what the relationship between theory and practice is, and how pitch relates to musical form, texture, and visual extra-musical depiction. Therefore, this piece cannot be considered artistically insignificant. This ‘crowd pleaser’ represents the completion of one of a number of dialectic cycles in Rautavaara's output and is a meeting ground for aspects that work in tandem – national versus international elements, musical versus extra-musical, modern versus traditional, and the exotic versus the authentic. The wide success of certain of Rautavaara's works nevertheless gave him pause for reflection:

I have found in my own case and in the work of others that a composition on which great expectations are pinned – that this one is absolutely bound to find its mark and so on – may turn out to be a non-starter, however it is packaged. And the more effort you make, the less likely you are to get the desired response. Then again, a piece that you didn't really take so seriously – it might be a commissioned work or a ‘potboiler’ done on the side – suddenly turns heads around the world, all by itself. And the composer stands there with his eyebrows in a knot and wonders what on earth it is they all see in it.Footnote 122

While musical economy and neo-tonality certainly play a part in the international success of Cantus, the wider, extra-musical references make them exist in the background for many listeners. But the evocation of these external factors challenges the composer to utilize a controlled and individually tailored set of musical techniques. A quieter, but no less relevant, novelty is therefore found. The importance of craft seems to be an extension of Rautavaara's advice never to ‘force your music, because music is very wise and has its own will’,Footnote 123 and the fact that he considered himself the ‘midwife’, rather than the mother, that helped his music come into being.Footnote 124

Characteristically, Cantus asks for these perspectives that might be regarded as mutually exclusive. It does not deny exoticist interpretations that enable wide popularity and dissemination, but delving deeper into the musical, historical, and ecological contexts around this piece proves a highly rewarding, and sometimes surprising, process.