Introduction

Christianity is in decline in British society.Footnote 1 According to the widely respected British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey, the proportion of the population identifying as Christian fell from almost two-thirds in the mid-1980s to less than half by the early 2010s—for the first time being overtaken, very slightly, by those specifying no religion (Field Reference Field2014b). Over roughly the same period, membership of UK churches fell by almost one third, from around 7.5 million in 1980 to 5.4 million in 2013 (Brierley Reference Brierley1997, Reference Brierley2014), at a time when the overall population continued to grow. On the foundational tenet of the existence of God, assent dropped by roughly the same margin as Christian affiliation, from three-quarters in the early 1980s to less than three-fifths almost three decades later (Clements Reference Clements2014). There have also been notable shifts within the religious population. Church of England affiliation has fallen most dramatically—collapsing from two-fifths to one-fifth of the population between the mid-1980s and the early 2010s, according to the BSA—although downward trends are also evident within Catholic and some non-conformist traditions. At the same time, some smaller and newer Christian traditions have grown—though not compensating for overall decline—as have non-Christian religious identities (Brierley Reference Brierley2014; Field Reference Field2014b).

The consequences of Christianity's declining position for politics, and specifically for the activities of Christian groups that seek to influence public policy, are difficult to predict. On the one hand, it might be expected that they have become less powerful political players, with fewer resources at their disposal and a receding capacity to appeal to the public. Certainly, confidence and trust in the church and its ability to answer social problems are relatively low, while a growing proportion of British people are opposed to religious leaders attempting to influence government decisions (Field Reference Field2014a; Clements Reference Clements2015). Religious interests and arguments that might have in the past been widely comprehensible are likely to be less resonant today—reflecting a more broadly observed deterioration in “religious literacy” (Dinham and Francis Reference Dinham and Francis2015), and potentially presenting challenges for how these groups “frame” their policy demands (Kettell Reference Kettell2017). Churches may plausibly retreat into a narrower range of public policy concerns as they seek to stem the flow of weakening social authority.

Yet decline is not the whole story. While the number of active adherents is falling, the absolute figures remain large and compare well to other institutions such as political parties (Keen and Apostolova Reference Keen and Apostolova2017). Neither is religiosity binary: there remain widespread softer forms of Christian identity—so-called “fuzzy fidelity” (Voas Reference Voas2008) or “believing without belonging” (Davie Reference Davie1994)—and there is evidence that at least some of these individuals may be more positive in their attitudes toward a public role for religion than those without any religious affiliation (Wilkins-Laflamme Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016). Christian language and imagery continues to leave an imprint on British society (Knott, Poole, and Taira Reference Knott, Poole and Taira2013), while in some cases the churches even possess formal legal advantages, notably the establishment of the Church of England and the right of its senior clergy to speak and vote in the UK legislature (Morris Reference Morris2009). Meanwhile, growing religious diversity may produce a greater absolute number of Christian organizations with policy interests, performing new roles in civil society. Even declining religious fortunes may serve to enhance the enthusiasm of the remaining faithful for active public faith (Achterberg et al. Reference Achterberg, Houtman, Aupers, de Koster, Mascini and van der Waal2009; Wilkins-Laflamme Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016). The churches thus retain important strengths within British society—through their adherents, Christianity's influence on culture, and some more formal institutional advantages—and these too may affect Christian groups' policy work.

This paper examines the activities of “Christian interest groups”—that is, organizations with a Christian character that attempt to influence public policy—within this complex socio-religious context that “push[es] and pull[s] in different directions” (Davie Reference Davie2015, 3). Drawing on a survey of Christian organizations and interviews with group representatives, it offers the first ever academic analysis of the UK Christian interest group “sector” as a whole, shedding light on their engagement, strategies, and influence.

The paper is structured into six main sections. It begins by reviewing the literature on religious (and mainstream) interest groups in the light of the changing place of Christianity in UK society. This is followed by a second section summarizing the data and methods underpinning the present research. The remainder of the paper then reports the research findings. In the third section, an overview of the extent of Christian interest group activity is presented, followed by a fourth outlining their most popular policy interests. The lobbying strategies employed by Christian interest groups are explored in the fifth section—in particular, whether they use “insider” or “outsider” tactics, and whether they “frame” their arguments in explicitly religious terms—while a sixth considers the impact of this lobbying. The paper ends by summarizing the findings of the research as a whole, concluding that the engagement, strategies and influence of Christian interest groups reflect Christianity's decline, but also its continued strengths within British society.

Christian Interest Groups: Considerations From Existing Literature

Interest groups have long been studied by political scientists as central to democratic politics and policymaking. According to one standard definition, interest groups are organizations that aim to influence public policy but do not formally seek public office (Beyers, Eising, and Maloney Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008). This paper looks at such organizations in the UK that have a Christian character—a potentially wide category that includes church denominations, charities and other bodies. While there has been comparatively little research that explicitly examines religious interest groups, some analyses have been conducted—most notably in the US (Hertzke Reference Hertzke1988; Hofrenning Reference Hofrenning1995; Knutson Reference Knutson2011, Reference Knutson2013), but also a small amount concerning the UK (e.g., Kettell Reference Kettell2016a; Steven Reference Steven2011). Indeed, one recent review of the political science subfield of politics and religion suggested that “the influence of religious groups in policy-making processes” is an understudied topic worthy of greater investigation (Kettell Reference Kettell2016b, 218).

A first step in any such enterprise is to document the extent of this activity. A number of studies have identified the most important religious interest groups in the US, especially those active in Washington DC (Hertzke Reference Hertzke1988; Hofrenning Reference Hofrenning1995; Knutson Reference Knutson2011; Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2012). In the UK, while scholars have analyzed key individual organizations or policy episodes (e.g., Steven Reference Steven2011), and their grassroots supporters (Hatcher Reference Hatcher2017), the most comprehensive effort to map the sector and its priorities focused on a specific subset: socially conservative “Christian Right” campaign groups (Kettell Reference Kettell2016a). Thus far, however, there has been no comparable academic analysis of the UK Christian interest group sector as a whole. Better understanding of the shape of this sector is of particular interest in view of the UK's changing socio-religious landscape. One possibility is that the decline of UK Christianity may have dampened the overall scale of Christian lobbying activity—as perhaps implied by one study that uncovered a decline in the number of UK associations with a religious character, in sharp contrast to the US (Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, FR, JD, Bevan, Greenan, Darren and Jordan2012), an outcome that could have enduring consequences for future policy debates in which religious voices have traditionally featured. Alternatively, if the volume of Christian organizations is increasing, perhaps partly due to greater diversity of Christian traditions (Brierley Reference Brierley2014; Wharton and de Las Casas Reference Wharton and de Las Casas2016), this could increase the numbers operating as interest groups.

Even less is known about the characteristics of Christian interest groups active in the UK. Studies of similar groups elsewhere have sought to categorize them—typically beginning with “denominations” but also often incorporating membership groups, professional organizations, coalitions, and those representing religious institutions (Weber and Jones Reference Weber and Jones1994; Zwier Reference Zwier and Stevenson1994; Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2012)—but no similar exercise has been performed in the UK. Another common distinction for mainstream interest groups is between “sectional” and “cause” groups, based on whether they represent the interests of members or promote particular causes (Hopkins, Klüver, and Pickup Reference Hopkins, Klüver and Pickup2019). While religious groups might be expected to fall into the latter category, they do also have sectional interests that might inform their policy work (Warner Reference Warner2000; Gill Reference Gill2001). Finally, and as already mentioned, some prior attention has been paid to socially conservative Christian campaign groups (Kettell Reference Kettell2016a, Reference Kettell2017). Yet, although such organizations may be especially visible, it is not known to what extent they are representative of Christian interest groups more broadly in the UK.

Closely connected to the type of organization is their issue agendas—that is, the policy issues on which they attempt influence. Much of the existing research into UK Christian interest groups has focused on traditional “moral” issues such as embryology and same-sex marriage (Kettell Reference Kettell2010, Reference Kettell2019)—yet among the grassroots, even the UK's evangelical constituency has much wider concerns (Hatcher Reference Hatcher2017). While there has been some consideration of more mainstream issues (Kettell Reference Kettell2013a), the extent to which these are prioritized by the sector as a whole is less clear. Academic studies of US religious interest groups have indicated a surprisingly broad range of policy interests. Knutson (Reference Knutson2013, 62) observed two sets of religious coalitions within most states, indicating different types of issue agenda: “a traditional values coalition and a social justice coalition”. The Pew Forum's (2012) survey uncovered engagement with around 300 distinct policy issues, ranging from traditional morality to more mainstream concerns. Once again, it appears plausible that the broader socio-religious context may play a role, for instance with declining Christian religiosity provoking some to emphasize traditional values.

Within the wider interest group literature, significant focus has been on groups' lobbying strategies. Particular attention has been paid to whether they employ “insider” or “outsider” tactics—the former being those aimed directly at policymakers (e.g., government or parliament) and the latter indirectly (e.g., via media or grassroots supporters) (Kollman Reference Kollman1998; Baumgartner et al. Reference FR, JM, Hojnacki, DC and BL2009; Binderkrantz and Krøyer Reference Binderkrantz and Krøyer2012). These strategies were traditionally assumed to be connected to groups' statuses in relation to policymakers, with those excluded from insider access falling back to outsider approaches, although the reality is not as simple as this suggests (Maloney, Jordan, and McLaughlin Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994; Page Reference Page1999; Binderkrantz Reference Binderkrantz2005). Even so, the distinction between insider and outsider strategies is interesting when applied to religious interest groups. In the context of wider socio-religious change, in which Christianity is losing its status yet also retains at least some of its cultural and institutional connections, one question is whether Christian interest groups are forced into outsider “protest” strategies, or whether they are able to make use of insider connections. Indeed, the popular debate around religion in UK society has seen rival claims that Christianity faces “marginalization” from the public sphere (Kettell Reference Kettell2009, 424) and that religion possesses “legal and political privileges” (Kettell Reference Kettell2015, 376). Moreover, it has been suggested that religious lobbyists may be particularly drawn toward outsider strategies for ideational reasons: some of the US research has found that many groups adopt a “prophetic” style that eschews insider compromise and negotiation, in part informed by religious commitments (Hofrenning Reference Hofrenning1995). The notion of religious interest groups as outsiders by natural inclination is similar to Grant's ([1978] Reference Grant and Rhodes2000) early category of “ideological outsider” interest groups.

A further dimension of interest group strategies is how they frame their arguments. This may be connected to the insider/outsider distinction, since organizations excluded from policy forums may seek to present their demands in ways that appeal to popular audiences (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993). US religious interest groups have been found to present their policy demands in relatively secular terms in order to appeal to non-religious audiences (e.g., Hertzke Reference Hertzke1988, 88), although more explicitly theological language may be used when communicating with supporters (Kettell Reference Kettell2013b; Kraus Reference Kraus2009). Yet there may also be specific factors associated with the UK's complex socio-religious context. Declining comprehension of Christian concepts is likely to make explicitly religious language less effective: Kettell (Reference Kettell2017) found that secularization had presented such challenges to conservative Christian groups, leading them to instead frame their arguments around the secular theme of religious liberty. Even so, as highlighted above, the embeddedness of Christian ideas and themes within UK culture may serve to offset some of the challenges. Interestingly, some US and comparative studies have found that religious interest groups may frame issues in “moral” terms (Knutson Reference Knutson2013, 96; Grzymała-Busse Reference Grzymała-Busse2015, 10), potentially a looser frame than an explicitly theological one. Once again, the dilemmas of framing issues to different audiences are not unique to religious organizations—for example reflecting the tension between the “logic of influence” and the “logic of membership” among other interest groups (Binderkrantz Reference Binderkrantz2020, 574).

Ultimately, interest groups seek to influence policy outcomes; indeed, it is for this reason that religious lobbying is often controversial. Yet assessing the influence of interest groups can be exceptionally challenging—in the words of one leading scholar, representing “the Holy Grail of interest group studies” (Leech Reference Leech, Maisel and Berry2010, 534). Among studies of US religious interest groups, the overall conclusion is that there has been no “rigorous assessment of effectiveness” (Guth Reference Guth, Burdett, Francia and Strolovich2012, 244). If the churches are declining in UK society, we might naturally expect them to be less capable of achieving successes. Kettell (Reference Kettell2016a, 1) observes that UK conservative Christian lobby groups are “typically considered to exert little practical influence”. Even in the case of the Church of England, despite its established status and presumed greater access, influence has been questioned—partly because establishment may temper its behavior (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2003, 210), but also because it does not enjoy strong social authority (Grzymała-Busse Reference Grzymała-Busse2015, 333). In addition to direct policy change, other forms of “interim interest group success” should also be taken into account, for instance in shaping the policy debate or on setting the policy agenda (Leech Reference Leech, Maisel and Berry2010, 536). Nor does interest group policy influence solely comprise change. Some groups have an interest in maintaining the status quo (Baumgartner et al. Reference FR, JM, Hojnacki, DC and BL2009), engaging in “counteractive lobbying” (Austen-Smith and Wright Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994) to “avoi[d] an even worse outcome” (Dür Reference Dür2008, 561)—a situation that may apply especially well to religious organizations whose influence on social norms is in decline. Analyzing the nature of Christian interest group influence in the UK may thus have wider implications for understanding the dynamics of religiously based policy influence elsewhere.

Data and Methods

The aim of this research was to provide the most comprehensive analysis to date of the engagement, strategies and possible impacts of the UK Christian interest group “sector” as a whole. The study sought to gauge the extent to which the most important Christian organizations behave as interest groups on UK-level public policy,Footnote 2 as well as to begin to understand their activities and impacts. The findings of this research are important in their own right, but also facilitate more in-depth future study. Two main research methods were employed. The first was a survey, which provided a source of both qualitative and basic quantitative data about the most important organizations within the sector.Footnote 3 The second was a series of interviews with Christian group representatives, which allowed for more nuanced explorations. In total, representatives of over 60 Christian organizations participated in the research.

The survey was sent to over 111 UK Christian organizations, with a response rate of 54% (60 organizations)—well above the typical rate for such exercises (Marchetti Reference Marchetti2015).Footnote 4 A common sampling method for interest group surveys is to begin with pre-existing published lists of organizations (Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, FR, JD, Bevan, Greenan, Darren and Jordan2012). This was not available for Christian groups as a whole in the UK, but there are good data sources listing denominational bodies.Footnote 5 Drawing on a variety of such sources, 74 of the most important denominations were identified, ranging from large and high-profile institutions to smaller and less well-known ones.Footnote 6 All respondents were invited to identify additional organizations that either represented the views of their congregants or members, or which formally represented the respondent's organization itself. This resulted in a further 37 “other Christian” organizations that were also sent a version of the survey.Footnote 7 Respondents were asked whether they ever sought to “inform, influence or engage with [UK-level] government policy”. This description was designed to cohere with standard definitions of interest groups (Beyers, Eising, and Maloney Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008), whilst also being sensitive to findings that some religious groups may be uncomfortable with explicit language of lobbying (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life 2012). The survey enabled an assessment of the extent of interest group activity by Christian groups overall, as well as providing answers to a range of questions about their issue agendas, strategies, and possible impacts.

Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with representatives of Christian organizations, most of which also responded to the survey. Around 20 interviews were carried out with representatives of 15 Christian organizations—of which seven were from denominational bodies and eight from other Christian groups. These made it possible to obtain greater detail than was available through surveys, including by asking interviewees to elaborate on survey responses. In addition to informing interpretation of the survey data, comments from some interviewees are cited below.

The remainder of the paper discusses the findings in greater detail. Because the next section documents the overall shape of the Christian interest group sector, this discusses denominational bodies and other Christian groups separately. Thereafter, the main quantitative results are presented for all respondents combined. While some distinctions are drawn in the text, the overall conclusions are largely similar across both categories of Christian group.

The UK Christian Interest Group Sector

An initial topic highlighted above concerns the overall extent to which Christian organizations act as interest groups in the UK. Of the 60 organizations that responded to the survey, 48 (80%) stated that their organization did seek to inform, influence or engage with UK-level policy, suggesting that interest group behavior among Christian organizations is likely to be fairly extensive.

Denominational Bodies

The first set of results relates to denominational bodies, which represent different Christian traditions. In the UK these range from large and high-profile organizations (such as the Church of England, and the Catholic Church in England and Wales) to smaller but also widely known bodies (such as the Methodist Church in Britain, the Salvation Army, the Baptist Union of Great Britain, and Quakers in Britain) to a wide range of smaller and lower-profile ones (e.g., representing newer traditions or those primarily based overseas).

Of 37 denominational bodies that responded to the survey, 27 (or 73%) stated that they were active on public policy. Although the precise figures must be treated with some caution—it seems likely that those with active policy work were the most likely to respond, while the sample size is fairly small—the findings do indicate that public policy engagement is relatively widespread and not limited only to the most high-profile denominations. Indeed, those stating that they were policy-active included both well-known and less familiar organizations. The priority that groups placed on interest group activity clearly varied considerably: of the 27 policy-active groups, almost all (22) stated that they had personnel responsible for policy work, although in some cases it was fairly minimal. In general, the largest and best-known denominations tended to report the biggest teams, with some reporting around seven or ten staff, sometimes with others also feeding into the work.Footnote 8 By contrast, one small evangelical denomination responded that it had one staff member who worked on policy issues for around 1 hour per month, while other groups relied on senior clergy (e.g., bishops) or volunteers. These responses suggest that a growth in the number of denominations may have increased the absolute number acting on policy, though clearly there is much variation in the intensity of their work.

The research indicated at least three factors explaining why denominations limited their engagement with UK-level public policy. First, some denominations operate principally in parts of the UK with devolved governments (i.e., Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland), and these tended to focus much of their policy work there. Hence, for example, a Scottish denomination reported that “[t]he little amount of work we do in this area is mostly related to [the Scottish Parliament in] Holyrood not Westminster”. As such, the numbers acting as interest groups at any governance level may be higher than the above figures suggest. In addition, however, some groups clearly lacked the resources to pursue policy work. One survey respondent stated that “we have no resource to do so”. Third, and linked to the question of resources, some inevitably prioritized their core religious functions.

Another question explored through interviews is whether denominational bodies consider themselves to be “interest groups”. Often groups distanced themselves from this language. An interviewee from the Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales commented that the Church sees itself as “encouraging lay people to get involved in politics […] rather than seeing it as an institution and a lobby”, while an interviewee from the Church of England observed that “the churches do not really conceive of themselves, and I think the Church of England particularly doesn't conceive of itself, […] as a political player in the sense of being an interest group with its own agenda it's trying to advance politically”. Others were more accepting of the term: when asked whether Quakers in Britain behaved more like a traditional pressure group than some other denominations, an interviewee agreed that it did, adding that it is “much more campaigny in that way”. Even so, irrespective of whether these denominations would use the language themselves, many clearly meet the basic academic definition of an interest group outlined above.

Other Christian Groups

Alongside denominational bodies, 37 “other Christian” organizations were identified, mainly through survey responses, and are listed in Table 1. Of the 23 that themselves responded, 21 (91%) confirmed that they were active on UK-level public policy, while desk research indicated that the remaining two had done so in the recent past—again suggesting relatively widespread interest group activity.

Table 1. Other Christian groups identified by survey respondents

a CLAS was specifically stated in the survey question as an example of a group that might formally represent the group responding.

Note: Groups in italics are those identified by Kettell (Reference Kettell2016a) as belonging to the UK “Christian Right”. Number in parentheses is the number of unique surveys that mentioned the group as representing the organization or the views of its members.

One way of capturing the diversity of these organizations is to categorize them. The categories employed in existing studies to US groups (e.g., Zwier Reference Zwier and Stevenson1994; Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life 2012) were not easily applicable to the above organizations, so an alternative scheme was devised, based on desk research into their core functions—but these are comparable in their range to the existing typologies. Ten were classified as “denominational umbrella” bodies, which exist to represent denominations—notably the Churches' Legislation Advisory Service, which provides advice on issues of shared institutional concern.Footnote 9 However, the largest number were classified as “service providers,” for example those working on international development or domestic social issues. The next category was for “campaign groups,” defined as organizations whose primary purpose is to campaign on policy issues rather than to provide services—although in practice the boundary between this and the previous category is sometimes hard to determine. Two further groups have been classified as “professional” organizations. The remaining two groups were labeled as “other,” both of which are evangelical organizations that, in many respects, are similar to the denominational umbrella groups.

As with denominational bodies, then, the evidence suggests that interest group activity by other Christian groups is likely to be fairly extensive, in spite of wider declining religious commitments. Once again, there is much variation in the resources spent on policy work. Some of the largest organizations—for example some of the international development NGOs—reported significant levels of personnel. One large service provider reported around 15 staff, while another stated that it had 12. At the other end of the spectrum, some groups had relatively low levels of resource. One stated that it had 0.2 persons on policy work (full time equivalent), while others that reported being active on policy stated that they nonetheless had no personnel responsible for this.

Another issue highlighted above concerns the extent to which socially conservative campaign groups are representative of the wider Christian sector. In terms of the absolute number, only a minority of those above fall into this category. To better gauge their importance, Table 1 specifies the number of times each group was mentioned in a survey response. While there are slight methodological problems with reading too much into the findings—not least because the views of the respondents may not be representative of Christian congregants—it does provide an indication of the relative importance of different groups. Of the eight socially conservative organizations identified by Kettell (Reference Kettell2016a) (in italics), half were among the most commonly cited groups, with between eight and 20 respondents mentioning them—and the most commonly mentioned organization, the Evangelical Alliance, was named by a third of all respondents. Two of the remaining groups, by contrast, were mentioned by only one survey respondent (in both cases by one of the other groups identified by Kettell), while the two others received no mentions. More mainstream groups—in particular the international development organization Christian Aid—received a high number of mentions. According to this measure, then, conservative Christian campaign groups cannot be considered fringe bodies within the broader UK Christian interest group sector, as some are among the most prominent overall. Yet this is not universally true, and neither do these groups appear to necessarily be representative of the sector as a whole.

Issue Agendas

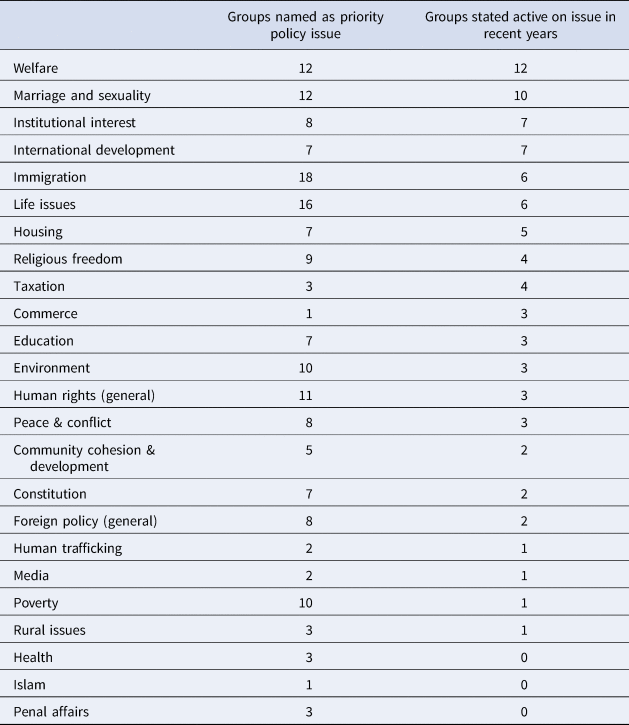

The second way of understanding the nature of the UK Christian interest group sector is to consider their issue agendas. The survey included two questions on this. First, respondents were invited to specify up to five “most important topics” on which they sought to inform, influence or engage with government policy, which were then placed into categories by the researcher. Second, they were asked for examples of specific legislation or policy developments with which they had engaged in recent years, and the answers were coded into the same categories. Both sets of results are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Policy issues identified by Christian interest groups

N = 48 (all policy-active groups).

Questions: “What are the most important topics on which your [church] organization actively seeks to inform, influence or engage with government policy? (Please specify up to five topics.)”; “Have you engaged with any specific pieces of proposed legislation (e.g., bills considered by parliament), or any other specific government policy developments, in recent years? Please give details.”

Note: Figures refer to the number of groups that specified this issue for each of the two questions. Where the same group gave multiple responses in the same category on the same question, it was counted only once.

An initial finding is that UK Christian interest groups engage with a very wide range of policy issues, covering the responsibilities of almost every central government department. This is partly because some “other Christian” groups have policy specialisms, which when aggregated produces diversity across the sample as a whole. In addition, many of the groups, including denominational bodies, have wide-ranging policy concerns. Of the 24 policy categories in the table, denominations specified 22 as among their priority policy issues, and stated that they had been active on 19 in recent years (the equivalent figures for “other Christian” groups are 21 and 15). An interviewee from one group described its policy work as covering “every issue under the sun, everything from slavery issues, to consumerism, to welfare, to radio and broadcasting licensing, I mean, you name it.” Variations on this statement could easily apply to many of the groups studied.

The socially conservative “moral” issues with which Christian interest groups are frequently associated are well-represented in the table. Among the most commonly cited priorities were “life issues” (e.g., abortion, assisted dying and bio-ethics) and marriage and sexuality (e.g., same-sex marriage, and the teaching of LGBT issues). Other topics listed may indirectly relate to such concerns, for example religious freedom (often centering on a freedom to act on socially conservative values) and commerce (all of which mentioned Sunday trading, perhaps linked to traditional morality). It can be assumed that these groups typically advocated a more traditionalist position, although this was not exclusively the case, and one group active on same-sex marriage specified that it lobbied in a liberal direction. Among the socially conservative campaign groups identified previously, these issues were particularly well-represented—marriage and sexuality was the top priority issue, with education, life issues and religious freedom also featuring highly.

Most of the issues in the table are, however, more mainstream policy concerns—and, like the equivalent Pew Forum (2012) study in the US, these span both domestic and international policy issues. Indeed, the most commonly cited priority issue was immigration, while the top issue on which groups had engaged in recent years was welfare (i.e., social security). An issue very closely connected to the latter was poverty, defined to incorporate a range of domestic issues such as food poverty, debt, and socio-economic equality. Other mainstream topics included the environment, peace and conflict, housing, health, and education. In many cases, Christian interest groups had policy concerns that reflected the broader demographics of their supporters or members. So, for example, some groups based in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland raised “constitutional” issues, which related primarily to matters such as Brexit or devolution that particularly affected those territories. Likewise, two denominational bodies that were branches of churches based principally outside the UK identified foreign policy concerns relating to the areas of the world in which their parent churches operated. This indicates that these Christian groups do not seek to influence policy solely as an expression of abstract religious values, or even in reaction to their declining religious fortunes, but in a way that is also partly rooted in their broader communities.

The list of policy issues in Table 2 also highlights the distinction between Christian organizations as either “sectional” or “cause” interest groups. Many of the issues listed are most plausibly in the latter category. Christian groups have little obvious institutional self-interest in policy on issues such as immigration, welfare, the environment, international conflict or penal affairs—and, even though a case could be made that defense of traditional social values protects the churches' institutional authority, it seems fairer to classify these too principally as “cause” concerns. In other cases, there are more obvious “sectional” interests—most obviously the category labeled “institutional interest” (comprising responses such as charity law, buildings, burial and cremation). Other issues combine both categories—notably education policy, on which some Christian groups have clear sectional interests around the teaching of religious education and the delivery of education services, in addition to value-based concerns. In particular, around a third of maintained mainstream schools in England have either a Church of England or Roman Catholic character (2019 figures, from Long and Danechi Reference Long and Danechi2019), leading both churches to substantial involvement with this issue.

In interviews, groups typically justified “cause” interests by reference to theological and religious values, but not “sectional” ones. So, for example, interviewees referred to their work on the former as reflecting the fact that “we, like all Christians, are called to promote the Kingdom of God on earth” and that “we are compelled to put our faith into action.” One large denomination distinguished between, on the one hand, issues on which “there's a gospel imperative to say something” or “an issue of moral principle” and, on the other, matters on which “there is a direct institutional interest of the Church in play.” These findings suggest that it is a mistake to view religious interest groups solely as cause groups motivated by religious convictions.

Lobbying Strategies

Both the survey and the interviews were also used to probe the extent to which UK Christian interest groups employed different lobbying strategies. This section begins with insider and outsider strategies, before considering their framing strategies. In both cases, the findings are discussed in relation to wider religious trends.

Insider and Outsider Strategies

To understand whether Christian interest groups employ predominantly insider or outsider strategies, the survey asked respondents about their use of ten common interest group tactics. Eight of these were designed to correspond to the categories of strategy outlined by Binderkrantz and Krøyer (Reference Binderkrantz and Krøyer2012): government and parliament (insider), and media and grassroots (outsider). To these were added two additional outsider strategies frequently associated with (especially conservative) religious interest groups in the US: litigation through the courts, and electoral mobilization (Guth Reference Guth, Burdett, Francia and Strolovich2012). The results are presented in Table 3, listed in order of their importance.

Table 3. Christian groups' use of policy tactics

N = 48 (all policy-active groups).

Question: “Which of the following activities has your organization used when seeking to influence government policy?”.

Notes: “Weighted total” calculated from scores of: major use (2), minor use (1), not used (0).

As can be seen, the findings indicate no obvious preference for insider or outsider strategies, instead suggesting a range of tactics. While the most important tactic was encouraging supporters to write to their elected representatives (an outsider tactic), the next three responses are all insider tactics: contacting parliamentarians directly, responding to a government consultation, and direct contact with government representatives. Yet the remaining insider tactic—direct participation in parliamentary proceedings—appears further down the list. Meanwhile, the two tactics drawn from the US, which may be regarded as especially disruptive forms of outsider strategy, reported very low levels of usage among respondents. To assess the potential advantages of the Church of England's formal legal status, respondents were also asked about the importance of various parliamentary contacts, including the Church's formal representatives in the House of Lords (the Lords Spiritual, i.e., bishops) and the elected House of Commons. Both of these featured relatively low down the list, with just 12 of 48 for the former, and 3 of 48 for the latter (in each case, two-thirds were from “other Christian” groups).

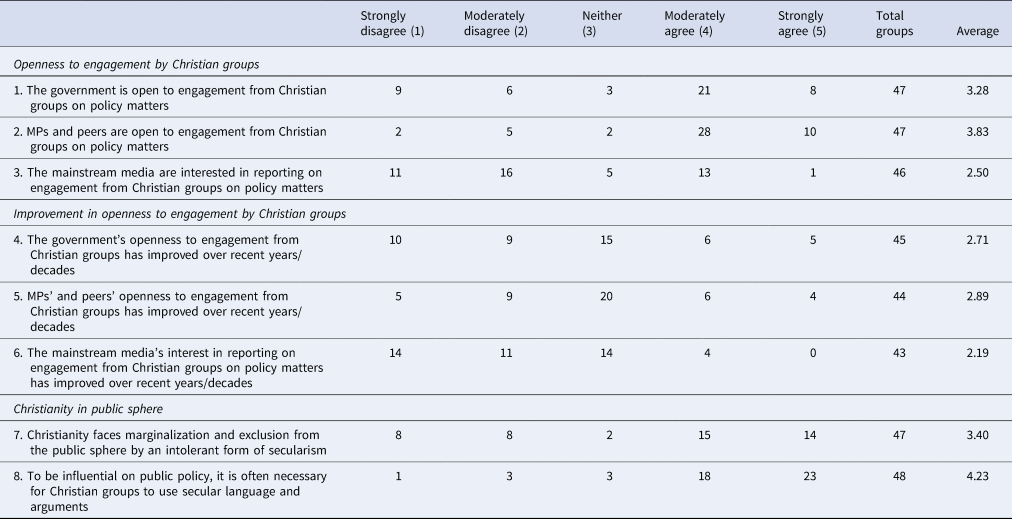

Another way of examining insider and outsider strategy selection is to consider groups' perceptions of how open policymaking is to their involvement—indicative of their wider status and access. The survey therefore asked respondents whether they agreed with a series of statements, the results of which are presented in Table 4. The first three (1–3) assessed whether groups considered that government, parliamentarians and the media were open to policy engagement by Christian groups. As can be seen, attitudes in relation to government and parliament were largely positive, reaching almost four-fifths for the latter. Interestingly, it was the mainstream media (an outsider venue) that was regarded as least open. The second set of statements (4–6) probed assessments of change over time, on which there was little obvious evidence of any shift. These findings do not appear to suggest that Christian interest groups are forced into outsider strategies due to lack of access.

Table 4. Openness of key policy actors to engagement by Christian pressure groups, and place of Christianity in public sphere

N = 48 (all policy-active groups).

Question: “To what extent do you agree with the following statements?”

Notes: “Total groups” excludes those that selected “no view/unsure” or did not complete the question. “Average” calculated by scoring responses on a 5-point scale (strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5) and dividing by the total number of groups selecting one of these options.

A remaining statement tested perceptions of a more general sense of outsider exclusion from the public sphere. According to Kettell (Reference Kettell2009, 424), central to the “public discourse” of Christianity in the UK is a shared belief among Christian figures that “religion in general (and Christianity in particular) faces marginalization and exclusion from the public sphere by an intolerant form of secularism.” A version of this statement was included in the survey (statement 7). The results generally support Kettell's analysis, with almost two-thirds of respondents indicating agreement—but this was not universal, and almost a fifth strongly disagreed. In interviews, some added further nuance. One large denominational representative commented that “we need to keep a sense of perspective about secularism and hostility. It's clearly there, it gets reflected in the media, but I don't get any sense that we're being pushed out of the public square.” An interviewee from a campaign group stated: “nobody's ever said “you've got no right to say that because you're [a Christian group].” They're quite happy for us to play a role.” A large NGO that responded to the survey likewise commented that “most of government is ‘agnostic’ about Christianity,” with the religious identity neither guaranteeing nor preventing access to its representatives.

These findings on strategy most likely vary between Christian organizations. An interviewee from the established Church of England described it as “less campaigny” than some other groups, as “We try and influence from within, if you like—we're part of the establishment—rather than without.” Conversely, an interviewee from Quakers in Britain situated them at the “protesting” end of the spectrum, commenting that this means they can “get into places that the Church of England can't.” This suggests that the preference for “prophetic” stances, identified in some of the literature, probably varies between groups. Similarly, it seems likely that status and access varied by group. One small denomination that responded to the survey noted that “[t]here is a tendency […] for Government consultations only to involve the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church”, leaving other groups “frequently entirely neglected”. An interviewee even from one relatively prominent denomination commented that it was not “in the same position as the Church of England as having an automatic foot in the door,” thus requiring it to “fight to be heard.”

Framing Strategies

The second important dimension of group strategy examined is use of religious language and framing. As also featured in Table 4, survey respondents were asked whether “To be influential on public policy, it is often necessary for Christian groups to use secular language and arguments.” Of all of the statements in that table, this one received the strongest backing: only four respondents (8%) disagreed, while 41 (85%) agreed—including 23 (48%) who strongly agreed.

Interviews made it possible to explore in greater detail the reasons for this finding. In part, the responses reflect the fact that explicitly theological rationales are unlikely to be persuasive or understood when directed at external audiences, particularly against the backdrop of declining religious observance. A representative of one prominent denomination explained in interview that “we need to be understood” and that “if the words that you use are too far from everybody else's conversation, it can be misinterpreted.” Another commented that “[t]he vast majority of what we put into the policy domain is expressed in almost entirely secular terms”—although they added that their theology does nonetheless inform these positions. Similarly, a Christian campaign group working on mainstream social policy issues explained that while “theology helps frame what we do […] in terms of our engagement with public policy we don't frame that in theological terms, because that doesn't make sense if […] the actors that you're working with or aiming to influence don't come from a theological base”.

Nonetheless, decline is not the only explanation. On some issues theology is largely not central to their positions—including on many “sectional” issues such as how secular law affects the churches, and on detailed policy design issues. Use of religious framing also varies by intended audience. One denominational interviewee explained that “in part it depends on [the] audience”, adding that “if this is a resource for church members […] then you're going to use more overtly Christian language because that's the question that is being asked,” whereas when writing for a politician “what you want to convey is almost the outcome of that [theological deliberation].” Another group commented that when speaking to church-based supporters, “that's where the theological language is important, essential: in terms of speaking to our own constituency, and mobilising churches, Christians, church leaders.”

Some evidence also supported the suggestion that groups may draw on looser “moral” framing that is at least implicitly rooted in theology. When asked in interview about the use of theological language, for example, one denominational group representative explained that “there's a difference between morality and religious language.” Another, commenting on the behavior of the Church of England's bishops in the House of Lords, observed that they generally “don't tend to use overtly theological language in their speeches, [but] more statements like “it's morally right” or “it's morally wrong,” or just the fact of who they are and the fact that they're standing there with a purple shirt,” adding that the theological connection is usually an “implicit assumption.” Such displays presumably rely, to some extent, on the persistence of looser social familiarity with Christian language and concepts, suggesting that the UK's religious heritage continues to play some role in Christian interest group policy framing.

Group Influence

The final area of focus concerns the influence exerted by UK Christian interest groups. Although assessing this comprehensively is beyond the scope of this paper, groups' self-reported influence does provide a preliminary indication. The survey therefore asked respondents to detail examples of “success” (however defined) when engaging with government policy. This question was deliberately worded broadly, to allow groups to indicate forms of influence that went beyond direct policy change. The responses were manually coded into five categories of influence listed in Table 5.

Table 5. Christian interest group self-reported influence

N = 48 (all policy-active groups).

Question: “Have there been any cases in recent years when you have achieved a ‘success’ (however defined) when engaging with government policy? Please give details.”

Note: Responses were free-text, and could be coded against multiple categories of influence.

Around a third of the policy-active groups reported no influence on UK-level public policy (rising to two-fifths of denominational bodies). Others highlighted “interim” forms of success—for example on the debate, on a government review, or by gaining access. One group referred to specific activity around “high stakes betting machines and gambling related harm,” which were stated to have been ultimately taken up in a government review on the matter. A large denomination noted that “[s]uccess can be defined in a variety of ways,” including simply “raising an issue.” A small denomination that had unsuccessfully lobbied against same-sex marriage observed (presumably in relation to this legislation) that “[a]nother point of view was certainly publicly expressed and acknowledged.” Another group commented that it did “not necessarily see our engagement in terms of “succeed or fail” […] but in terms of having a good relationship where we can take part as much as we can and where we can make the case for the common good.” In interview, one representative explained: “sometimes there aren't things where you can say we've definitely made a difference in the legislation, but have we made a difference in the way people think about things?” Commenting on same-sex marriage legalization, another interviewee added: “I don't want to say too much that it was a whole great big failure. Because what I want to say is, it is just important to stand.”

Nonetheless, as shown in the table, almost half did report some influence on UK-level policy itself. These responses were manually coded into the 24 policy topics featured in Table 2, and the results indicate potential influence across a very wide range of issues, with at least one example given from 19 of the 24 policy topics.Footnote 10 The top category was “marriage and sexuality,” with four respondents indicating influence, three of which were in support of legalization of same-sex marriage—itself challenging simplistic caricatures of the sector. Other policy topics with at least two respondents included housing, welfare, commerce (Sunday trading), the environment, immigration, international development, religious freedom, and life issues. It can therefore once again be seen that the range of policy issues on which Christian interest groups report some policy influence is more varied than might be expected.

In terms of examples of policy change, one denomination heavily involved in issues around social security referred to “[p]ressure for mitigations in [the] Universal Credit system,” although presumably this was not solely down to this group. Another highlighted changes around charity law, for example “[g]etting charity exemption from the Community Infrastructure Levy.” Three large Christian-based NGOs working on international development issues referred to their contribution to the government's commitment to spending 0.7% of gross national income on aid. One of these groups acknowledged that “[w]e have usually not been the sole group lobbying for this” and similar issues, but had nonetheless “been a large and significant contributor to these coalitions.” Other examples cited by Christian groups included influencing the Foreign Office to “consider the views of faith-based leaders when they develop their Middle East strategy.”

In some cases, influence on policy did not take the form of change but of maintaining the status quo. This may be especially relevant on traditional moral questions, on which the authority of the churches is gradually ebbing away and yet where they retain some significant social strengths. Survey respondents, for example, cited “[d]efeat of plans to restrict freedom of churches to employ Christians” through the Equality Bill in 2010, and an apparent government u-turn on “plans to register and regulate all ‘out of school settings'” following a sustained campaign by the organization. One denominational body referred to the maintenance of Sunday trading restrictions—though noted that “obviously this was due to combined pressure from many different churches, trade unions, etc.”. Indeed, it may be that maintenance of the status quo is one significant—albeit less easy to detect—form of Christian interest group influence, both in the UK and in other similar contexts elsewhere.

Conclusions

This paper has provided the most systematic analysis yet of the Christian interest group sector in the UK. Based on a survey of Christian denominations and other groups, plus interviews, it has supplied an initial assessment of their engagement, strategies and influence, in the context of wider socio-religious trends. The findings suggest that Christian interest groups in the UK have been affected both by Christianity's decline and by its continued strengths within society—including changes in popular adherence, influence on wider culture, and formal institutional statuses.

Beginning with the extent of engagement, the paper found that public policy work by Christian organizations is widespread and is not confined to only the most high-profile bodies. In addition to denominations, a wide variety of other Christian groups operate as policy actors, including those representing the interests of denominations, charities providing services to different groups of people, and dedicated campaign groups. Christian interest groups are active on a wide range of policy issues, covering the responsibilities of almost the entire spectrum of central government departments. These include traditional “moral” issues (such as abortion and sexuality), but also many more mainstream policy concerns (such as welfare, immigration, and international development). Much of the time they operate as “cause” groups, pursuing objectives because they believe them to be best for society, but they also have “sectional” institutional interests.

Turning to groups' strategies, the results uncovered a complex picture. On the one hand, there is no clear inclination toward “outsider” tactics overall—either by necessity (due to marginalization) or by preference (arising from “prophetic” policy stances). They seem especially unlikely to use the highly disruptive outsider tactics of litigation and electioneering. In these respects, UK Christian interest groups appear to behave differently from their US counterparts, perhaps partly due to different opportunity structures (Bruce Reference Bruce2012, 107–21). The survey uncovered perceptions among some groups that Christianity faces marginalization from an increasingly secular public square, and this may be connected to a clear understanding that they must use secular language and arguments in order to be effective. Yet some Christian interest groups are also drawn to insider strategies—notably the Church of England, perhaps influenced by its established status. There is also evidence that some groups may be willing to make moral arguments that are implicitly underpinned by religious justifications—something likely only feasible due to Christianity's continued cultural imprint. Both decline and continued strengths therefore affect Christian interest groups' policy strategies.

Finally, in terms of impact and influence, the paper found evidence of widespread, albeit often modest, success—something not previously reported in much of the literature about religious interest groups in the UK or (to some extent) elsewhere. This included some small impact on policy shifts, but also wider influence on public policy debates. There are also indications that some Christian group influence may take the form of limiting policy change rather than securing it—an intriguing finding that may tell us much about the ways in which religious interests still matter in contexts of declining adherence.

Despite presenting the most comprehensive account to date of this sector, the scope of the research is also to some extent limited, focusing on a cross-section of the most important Christian interest groups in the UK. As such, many of the findings remain slightly provisional. They do, however, place existing studies of UK religious lobbying into greater context, and provide a solid basis for further study. Three areas of future research appear particularly fruitful. First, given issue diversity, further research is needed into Christian interest groups' engagement with topics other than the socially conservative priorities that have been analyzed so far—and whether the dynamics of activity differ across these policy domains. Second, the impact on group strategies both of Christianity's decline and its continued social strengths would be beneficial—for example, whether even loose appeals to Christian “morality” remain effective despite declining adherence. Third, a much deeper understanding of religious groups' influence in policymaking is required—extending not only to policy shifts, but also to defense of the status quo. Given that the UK's socio-religious trends are shared by other countries elsewhere, the findings of such endeavors are likely to have wider implications for understanding the connections between religion and democratic policymaking today.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/J500124/1].

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048321000274.