Abstract

In this paper, we demonstrate the generation of high-performance entangled photon-pairs in different degrees of freedom from a single piece of fiber pigtailed periodically poled LiNbO3 (PPLN) waveguide. We utilize cascaded second-order nonlinear optical processes, i.e., second-harmonic generation (SHG) and spontaneous parametric downconversion (SPDC), to generate photon-pairs. Previously, the performance of the photon-pairs is contaminated by Raman noise photons. Here by fiber-integrating the PPLN waveguide with noise-rejecting filters, we obtain a coincidence-to-accidental ratio (CAR) higher than 52,600 with photon-pair generation and detection rate of 52.36 kHz and 3.51 kHz, respectively. Energy-time, frequency-bin, and time-bin entanglement is prepared by coherently superposing correlated two-photon states in these degrees of freedom, respectively. The energy-time entangled two-photon states achieve the maximum value of CHSH-Bell inequality of S = 2.71 ± 0.02 with two-photon interference visibility of 95.74 ± 0.86%. The frequency-bin entangled two-photon states achieve fidelity of 97.56 ± 1.79% with a spatial quantum beating visibility of 96.85 ± 2.46%. The time-bin entangled two-photon states achieve the maximum value of CHSH-Bell inequality of S = 2.60 ± 0.04 and quantum tomographic fidelity of 89.07 ± 4.35%. Our results provide a potential candidate for the quantum light source in quantum photonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum correlated/entangled photon-pairs are serving as essential resources in quantum photonics, such as quantum key distribution (QKD)1,2,3,4, quantum teleportation5,6,7, quantum-enhanced metrology8,9, and linear optical quantum information processing (LOQC)10,11. Approaches, such as cascaded emissions in single-emitters12,13 and spontaneous parametric processes14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, are developed to generate correlated/entangled photon-pairs. The latter one includes spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC) and spontaneous four-wave mixing (SFWM), already widely utilized in several applications23,24,25,26,27,28.

The correlated/entangled photon-pairs at 1.5 μm are important for long-distance quantum networks. The generation of 1.5 μm bright photon-pairs has been demonstrated via SPDC process in β-BaB2O4 (BBO)29,30, periodically poled KTiOPO4 (PPKTP)31,32,33, periodically poled LiNbO3 (PPLN)18,26,27,28,34,35,36,37,38, and other second-order nonlinear optical materials39,40, or SFWM process in silica fiber14,41,42,43,44,45, silicon15,16,25,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, silicon nitride61,62, chalcogenide glass63, and other third-order nonlinear optical materials64,65,66. While the second-order nonlinear process is in general more effective than the third-order one, it often requires a sophisticated optical system capable to simultaneously manipulate light at quite different wavelengths67. Fortunately, a scheme of cascaded second-harmonic generation (SHG) and SPDC processes with two26,27,28 or a single waveguide67,68,69 has been developed to generate photon-pairs with second-order nonlinear optical devices at 1.5 μm. However, the performance of such quantum light sources is limited by the spontaneous Raman scattering (SpRS) noise. Although the SpRS noise has been experimentally investigated in those sources67, the further endeavor to suppress such noise for high-performance quantum light sources has not yet been reported.

In this paper, we obtain high-performance entangled photon-pairs in different degrees of freedom by cascaded SHG/SPDC processes in a single piece of fiber pigtailed periodically poled LiNbO3 (PPLN) waveguide. The SpRS noise photons are effectively eliminated by fiber-integrating the waveguide with noise-rejecting filters, i.e., fiber-based DWDMs. Photon-pairs with a coincidence-to-accidental ratio (CAR) higher than 52,600 are generated, with a generation rate and detection rate of 52.36 kHz and 3.51 kHz, respectively.

Entanglement in degrees of freedom of energy–time, frequency-bin, and time-bin are prepared by coherently superposing correlated two-photon states. The measured visibility of the Franson interference curve is 95.74 ± 0.86% for energy–time entanglement, indicating a maximum value of CHSH-Bell inequality of S = 2.71 ± 0.02. The prepared frequency-bin entangled two-photon states are reconstructed with the fidelity of 97.56 ± 1.79% by observing the spatial two-photon quantum beating with visibility of 96.85 ± 2.46%. The time-bin entangled two-photon states achieve a maximum value of CHSH-Bell inequality of S = 2.60 ± 0.04, and fidelity of 89.07 ± 4.35% measured via quantum-state tomography. Our results show that a high-performance quantum light source with cascaded second-order nonlinear processes on a photonics chip should be feasible.

Results

PPLN waveguide module with noise-rejecting filters

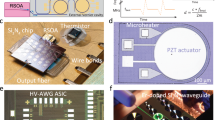

Figure 1a shows the design of PPLN waveguide module with noise-rejecting filters which consists of a bandpass filter (F1), a PPLN waveguide, a bandstop filter (F2). Two fiber pigtails are used to connect the waveguide and the noise-rejecting filters. The cascaded SHG and type-0 SPDC process could take place in the PPLN waveguide with a pump light to generate the correlated/entangled photon-pairs. The PPLN waveguide only operates in a single polarization mode that is parallel with the polarization of pump light. The noise photons generated by the pump light before the input port of the module can be removed by F1 and the ones caused by the residual pump light output from the PPLN waveguide could be effectively eliminated by F2. In other words, the noise photons from SpRS process are only generated within the proposed PPLN waveguide module. In our design, the fiber pigtails connecting the PPLN waveguide and noise-rejecting filters are both 20-cm long—limited by our fabrication process, in which few SpRS noise photons could be generated. In principle, these SpRS noise photons could be further reduced by getting rid of fiber pigtails in a fully integrated scheme, for instance we can directly integrate F1 and F2 on both ends of the PPLN waveguide in the future.

a The design of the PPLN waveguide module. The input pump photons at λp pass through the filter (F1), with the input noise photons removed. The SpRS process takes place in the two fiber pigtails, while the cascaded SHG/SPDC processes occur in the PPLN waveguide. After filter (F2), the residual pump light is smaller than the input one by about ~ 20 dB, which could reduce the SpRS noise photons by ~ 100 times in per unit length of the fiber. b Measured spectra of correlated photon-pairs with phase matching. c and d are the measured co- and cross-polarized Raman spectra in the PPLN waveguide module under the phase mismatching condition.

Table 1 gives main parameters of the PPLN waveguide module from HC Photonics. A piece of 50-mm long PPLN waveguide is fabricated by reverse proton exchange (RPE) procedure with a poled period of 19 μm. The normalized conversion efficiency of SHG process is 500 %·W–1 with pump light at 1540.46 nm. Two identical DWDMs with the central transmission wavelength at 1540.46 nm and bandwidth of ~ 200 GHz are used to reject the noise photons.

The single-photon level spectra of correlated photon-pairs and SpRS noise photons generated from the PPLN waveguide module are measured (see details in the spectra of noise and correlated photons in “Methods”). As shown in Fig. 1b, the correlated photon-pairs can be obtained in a broadband spectrum with a full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of ~ 60 nm, which are contaminated with different amounts of SpRS noise at different frequencies. Figure 1c shows the spectrum of co-polarized SpRS noise photons, which is quite distinct from the corresponding spectra in the pigtailed fiber (see Supplementary Note 3), while the spectrum of cross-polarized SpRS noise photons shown in Fig. 1d nearly has a similar profile with the corresponding spectrum in the pigtailed fiber (see Supplementary Note 3). This suggests that the SpRS noise photons are from both the fiber pigtails and the PPLN waveguide. A detailed investigation is given in Supplementary Note 2.

Entanglement generation with PPLN waveguide module with noise-rejecting filters

Quantum entanglement in different degrees of freedom is prepared and characterized with the setups shown in Fig. 2a–e. Figure 2a shows the experimental setup for generating correlated/entangled photon-pairs. The PPLN waveguide module is pumped by either continuous wave (CW) or pulsed laser, which is selected by an optical switch in our experiment. For both cases, the pump power is amplified, attenuated, and monitored by an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA), variable optical attenuator (VOA), and 99:1 beam splitter (BS) with a power meter, respectively. A dense wavelength division multiplexer (DWDM) with the central transmission wavelength at 1540.46 nm and a passband width of ~125 GHz is employed to suppress the amplified spontaneous emission noise from the EDFA. The polarization state of the pump laser is manipulated by a polarization controller (PC). A polarization beam splitter (PBS) is used to ensure the polarization alignment for maximizing the efficiency of phase matching in the PPLN waveguide. The correlated/entangled photon-pairs are generated by cascaded SHG/SPDC processes. An isolator is connected to the output port of the module to reject the residual second-harmonic (SH) photons at 770 nm70. Figure 2b–e shows setups for characterizing the quantum correlation of the generated photon-pairs, for characterizing the performance of the energy–time71 or time-bin entanglement43,72,73, for coherently manipulating two-photon state45, for preparing and measuring the frequency-bin entanglement31,35,44,45, respectively.

a Setup for preparing correlated/entangled photon-pairs. b Setup for characterizing correlated photon-pairs. c Setup for characterizing energy–time and time-bin entanglement. The synchronous signal is from AWG as shown in Fig. 2a. d Setup for coherently manipulating the energy–time-entangled two-photon state. e Setup for preparing and characterizing frequency-bin entangled photon-pairs. The λp in Fig. 2a is 1540.46 nm and λs,i = 1531.72 nm, 1549. 34 nm in (b–e). IM intensity modulator, EDFA erbium-doped fiber amplifier, VOA variable optical attenuator, PC polarization controller, BS beam splitter, PBS polarization beam splitter, DWDM dense wavelength division multiplexer, PPLN periodically poled LiNbO3, UMZI unbalanced Mach–Zehnder interferometer, VODL variable optical delay line, AWG arbitrary waveform generator, TDC time to digital convertor, SNSPD superconducting nanowire single-photon detector.

Generation of the correlated photon-pairs

Correlated photon-pairs are generated with setups shown in Fig. 2a, in which a CW pump at 1540.46 nm is used. The generated photon-pairs are sent into setups in Fig. 2b, in which the signal and idler photons at 1531.72 and 1549.34 nm are obtained by using two DWDMs with a FWHM bandwidth of ~125 GHz, respectively. The signal and idler photons are detected by two superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs, P-CS-6, PHOTEC, see Supplementary Note 6). A time to digital converter (TDC, ID900, ID Quantique) is used to record the counting rates of the signal and idler photons, and the coincidence events between them.

Figure 3a shows the measured counting rate of the signal photons under different levels of pump power, which are well fitted with a quadratic polynomial curve (black line). The quadratic (red line) and linear components (blue line) are corresponding to the contributions of generated photon-pairs and noise photons, respectively. It shows that the correlated photon-pairs generated in cascaded SHG/SPDC processes are dominant in the generated photons. Similar results are also obtained for idler photons (see Supplementary Fig. 1a).

a Photon-counting rate (black circle) in signal channel versus pump power. The black solid line is the quadratic polynomial fitting curve of the photon-counting rate with the quadratic and linear parts shown as the red and blue curves, respectively. The error bars are estimated by Poissonian photon-counting statistics. b Measured CAR versus pump power. The error bars are estimated from the statistical errors of the coincidence and accidental coincidence counts, in which the former is obtained by assuming Poissonian statistics and the latter is estimated by the standard deviation values of accidental coincidence in three 300-ps time windows away from the coincidence peak. The inset is the coincidence histogram between signal and idler photons when the pump power is set at ~2 mW, and a coincidence window of 300 ps is marked. c Results of Franson interference for β = −1.57 (red circle) and β = −0.64 (blue rectangle). d Results of two-photon interference (red circle) and single-photon interference (blue rectangle). The error bars of coincidence count in (c, d) are estimated by repeating the measurement three times, while the error bars of photon counts in (d) are obtained by Poissonian photon-counting statistics.

Figure 3b shows the coincidence-to-accidental ratio (CAR) calculated by CAR = Cc/Acc under different levels of pump power, where Cc and Acc are the coincidence count and accidental coincidence count, respectively. The inset of Fig. 3b shows a typically measured histogram with a pump power of ~2 mW, which is the accumulation of coincidence events in 20 s. The coincidence count is collected within a time window of 300 ps covering the coincidence peak, while the accidental coincidence count is estimated by the average of counts within three 300-ps time windows away from the coincidence peak (see Supplementary Fig. 1b). The CAR reaches a maximum value of 52,600 when the pump power is 0.27 mW.

With the results of signal/idler photon-counting rate and their coincidence counts, we obtain the generation rate and collection efficiency of photon-pairs via calculation (see Supplementary Fig. 1c and d). Finally, we can derive that our source achieves a photon-pair generation rate of 52.36 kHz with a CAR of 52,600, and 9.11 MHz with a CAR of 443. The calculated collection efficiencies of signal and idler photons are ~27% and ~ 23%, respectively, including the output efficiency of the PPLN module (~73%), the transmission efficiencies of isolator (~89%), and the DWDMs (~67%), as well as the detection efficiency of SNSPDs (~65%).

Performance of energy–time entanglement

The correlated photon-pairs generated in SFWM or SPDC process are naturally energy–time entangled when CW pump light is used meanwhile has coherent time longer than the generated photons after filters74. This type of entanglement has considerable potential in high-dimensional quantum key distribution (QKD)75. In our experiment, the generated photon-pairs under the CW pump are sent into setups in Fig. 2c to characterize the energy–time entanglement by the Franson interference71. In Fig. 2c, the signal and idler photons are first separated by DWDMs, and then pass through two unbalanced Mach–Zehnder interferometers (UMZIs, MINT, Kylia), respectively. The time delay difference between the long and short arms is 625 ps in both UMZIs, while an additional phase difference α or β between the two arms can be tuned by applying a voltage on a piezo actuator. In the experiment, we stabilize the phase of UMZI by using a feedback system (see the details in Supplementary Method). The photons from each output port of the UMZIs are detected by SNSPDs and the corresponding photon counts are recorded by the TDC.

In our experiment, three peaks appear in the coincidence measurement between signal and idler photons output from the port A1 and B1 in the UMZIs shown in Fig. 2c, respectively. To observe the Franson interference71, we select the coincidence counts in the central peak with a time window of 300 ps when the phase differences α and β are scanned and fixed, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3c, when β = −0.64 rad and −1.57 rad, the coincidence counts versus α can be well fitted with a cosine function showing visibilities of 95.74 ± 0.86% and 93.55 ± 3.15%, respectively, without subtracting the accidental coincidence counts. The deviation of the visibility from the unit can be attributed to the accidental coincidence, the unbalanced loss and imperfect beam splitting in the UMZIs, and the frequency instability of the pump laser. On the other hand, the signal and idler photon-counting rates are almost unchanged during the measurement, indicating that the fringes in Fig. 3c are the results of the quantum interference of the energy–time entangled two-photon state. The two curves shown in Fig. 3c can be utilized to further verify the violation of CHSH-Bell inequality for the energy–time entanglement72. The minimum visibility of violation of the Bell inequality is 70.7%, and so the Bell inequality is violated by 35 and 7 standard deviations when β = −0.64 rad (S = 2.71 ± 0.02) and −1.57 rad (S = 2.65 ± 0.09), respectively. Compared with a recent work76, our results represent higher visibility of the Franson interference.

With the setups shown in Fig. 2d, we coherently manipulate the energy–time entangled two-photon state by sending it into a single UMZI (see Supplementary Note 4). The coherent manipulation can prepare a superposition state of spatial bunched and anti-bunched path-entangled states, and the complex superposition coefficients of the two states can be fully manipulated by the additional phase φ in the UMZI. The spatial bunched path-entangled state is measured by the coincidence measurement between signal and idler photons from one output of the UMZI45, which is shown by the red circles in Fig. 3d. We can see that such coincidence shows cosinoidal oscillation with visibility of 94.58 ± 0.63% when the phase φ changes, indicating that the prepared state converts between the spatial bunched and anti-bunched path-entangled states. An attenuated CW laser is also injected into the UMZI shown in Fig. 2d and its single-photon interference is observed, the fringe of which is shown by the rectangle curves in Fig. 3d and has a visibility of 98.10 ± 0.01%. It is obvious that the period of the oscillation of coincidence between signal and idler photons is half that of the observed single-photon interference. Such difference verifies that our coherent manipulation of energy–time entangled state is based on the interference of matter-wave of the entangled two-photon state.

Generation of frequency-bin entanglement

Frequency-bin entanglement attracts much attention due to its potentials in quantum information processing17,77. In our scheme, we can obtain frequency-bin entanglement by coherently manipulating the energy–time entanglement45. As shown in Fig. 2e, the generated energy–time entangled photon-pairs are directly sent into a single UMZI, by setting the additional phase φ = π to prepare the photon-pairs to a spatial anti-bunched path-entangled state which is exactly a frequency-bin entangled state. The frequency-bin entanglement is characterized by the spatial quantum beating31,44,45. The two-photon state output from the UMZI is injected into a 50:50 BS with a relative arrival time delay τ between the two paths which is controlled by a VODL (variable optical delay line). To ensure the input photons of BS are in an identical polarization state, PCs and PBSs along the two optical paths are used. At the output ports of the 50/50 BS, signal and idler photons are selected by two DWDMs and are detected by SNSPDs, respectively.

Figure 4a shows the result of the spatial quantum beating. When the delay time τ is changed, the coincidence counts between signal and idler photons show modulated cosinoidal oscillation, i.e., a clear signature of frequency-bin entanglement31,44,45. The experimental data in Fig. 4a can be fitted by an expression (see Supplementary Note 4)

where Δτ = τ−τ0 with τ0 being the intrinsic time delay between signal and idler photons; C0 is a constant; V is the visibility; sinc(Ω·Δτ) describes the envelope of the spatial quantum beating and it is associated with the transmission spectra of DWDMs in Fig. 2e, approximated by a rectangular function with an angular frequency bandwidth of Ω; Δωsi is the difference between the central angular frequencies of the detected signal and idler photons. The fitting gives Ω = 2π × (116.35 ± 2.20) × 109 rad·s−1 and Δωsi = (2.22 ± 0.01) × 1012 rad·s−1 which agree well with the transmission bandwidth of 125 GHz and central wavelength of 1531.72 nm (1549.34 nm) of the DWDM for signal (idler) photons in our experiment. We also get V = 96.85 ± 2.46% and phase φ = 0.18 ± 0.06 rad. According to the method in Refs. 31 and78, the density matrix of the frequency-bin entangled state can be reconstructed by experimental measurements (see details in the reconstruction of frequency-bin entangled state in “Methods”). Figure 4b and c shows the real and imaginary parts of the reconstructed density matrix, which gives a target-state fidelity of 97.56 ± 1.79% with respect to the maximally entangled state \(\left| \psi \right\rangle = (\left| {\omega _s} \right\rangle \left| {\omega _i} \right\rangle + \left| {\omega _i} \right\rangle \left| {\omega _s} \right\rangle )/\sqrt 2\). Our result demonstrates that the frequency-bin entanglement has been successfully prepared based on cascaded SHG/SPDC processes. It is worth noting that in our experiment only a pair of frequency bins is selected, i.e., the frequency-bin entanglement78, which can be further prepared to an entangled frequency comb by using comb-like filters77,79.

a Spatial quantum beating of frequency-bin entangled state. b, c The real and the imaginary parts of the experimentally reconstructed density matrix of frequency-bin entangled photon-pairs, respectively. d The phase α + β dependence of the threefold coincidence between the synchronous electrical signal and the photons from the ports A1&B1 (red rectangle), A1&B2 (blue triangle), A2&B1 (purple inverted triangle), or A2&B2 (green circle). e Correlation coefficient E(α,β) calculated from the four curves in d according to Eq. (2). f, g The real and the imaginary parts of the density matrix of time-bin entangled photon-pairs, respectively. The error bars in a and d are all estimated from measurement results assuming Poissonian statistics, while the error bars in e are obtained via propagation of statistical errors according to Eq. (2).

Generation of time-bin entanglement

Time-bin entanglement is suitable for many types of quantum information applications involving long-distance fiber-based transmissions of photons72. The photons entangled in time-bin can be created when periodically repeated double pulses (see the preparation of double-pulsed pump light in “Methods” for details) are used to pump the PPLN waveguide module in Fig. 2a. The performance of the generated time-bin entanglement also can be characterized by the experimental setup shown in Fig. 2c. In this case, all the four output ports in the two UMZIs, namely, A1, A2, B1, and B2 are used.

The UMZI can project the time-bin qubit onto the time or energy bases when the time delay difference between the long and short arms of UMZI is equal to the interval of time-bins43. To select different bases, a synchronous electrical signal accompanying the generation of the double-pulsed pump light is introduced72. The Franson interference of time-bin entanglement can be observed by measuring coincidence between the projections of signal photon and idler photon on their energy bases. Figure 4d shows the threefold coincidence counts in a time window of 300 ps between the synchronous electrical signal, and signal (A1 or A2) and idler (B1 or B2) photons when the phase α in one UMZI is fixed and β in another UMZI is scanned. The coincidence counts involving the port combinations of A1&B1, A1&B2, A2&B1, and A2&B2 all show remarkable interference fringes, and the raw visibilities of them are 94.59 ± 2.43%, 92.12 ± 2.51%, 90.30 ± 2.36%, 94.05 ± 2.39%, respectively. Our results show that the time-bin entangled photon-pairs at 1.5 μm have been generated in our scheme, which can be applied in metropolitan quantum teleportation system6,7.

With those Franson interference fringes, the violation of CHSH-Bell inequality can be observed72. The correlation coefficient is defined as

where \(R_{A_iB_j}\) is the threefold coincidence counts involving the port combinations Ai (i = 1, 2) and Bj (j = 1, 2). According to the theory of Franson interference71, \(R_{A_iB_j}\) is proportional to 1 + (−1)i+jV cos(α + β), where V is the visibility of the interference fringes. The correlation coefficient calculated by Eq. (2) can be derived as E(α, β) = V cos(α + β) with a raw visibility of 91.75 ± 1.30%. The maximum value of CHSH-Bell inequality can be obtained as \(S = 2\sqrt 2 V = 2.60 \pm 0.04\), showing a violation of Bell inequality of up to 15 standard deviations.

The entanglement of the generated photon-pairs can be confirmed unambiguously by reconstructing the density matrix via quantum-state tomography43,73. As shown in Fig. 2c, we choose the output ports A1 and B1 from the two UMZIs and calculate the density matrix by projecting the time-bin entangled two-photon states onto 16 measurement bases (see quantum-state tomography of time-bin qubits in “Methods” for details). The coincidence counts obtained in the above projection measurements are summarized in Supplementary Note 5. As a result, we obtain the following density matrix:

The real and imaginary parts of this matrix are shown graphically in Fig. 4f and g, respectively, from which a fidelity of 89.70 ± 4.35% is obtained with respect to the state \(\left. {\left| {{\it{{\Phi}}}^ + } \right.} \right\rangle = \left( {\left. {\left| {11} \right.} \right\rangle + \left. {\left| {22} \right.} \right\rangle } \right)/\sqrt 2\) (|1〉 and |2〉 represent the qubit in early and late time-bins, respectively). The probable main causes of this limited fidelity include the imperfection in double-pulsed pump laser, such as nonuniform pulse intensity, instable phase difference between double pulses, and limited extinction ratio, as well as the error in the calibration of the phase of the UMZIs.

Discussion

In this paper, we demonstrated a high-performance entangled photon source. To show the performance of our entangled photon source, we compare the CAR and the raw detected photon-pair rate (DPPR) of our photon source with previous works in which various nonlinear optical media are employed18,34,36,37,38,42,47,48,52,55,66,67,69,80,81, as shown in Fig. 5a. The comparison shows that the performance of our entangled quantum light source has orders of magnitude improvement in DPPR (CAR) than other works under the same CAR (DPPR). Recently, the periodically poled thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN) nano-waveguides achieved a remarkable performance, better than more matured, macroscopic (nonintegrated) systems38. It could be useful for the future development of quantum photonic circuits using poled TFLN. Compared with this work, our source with the PPLN waveguide module can generate more photons by two orders of magnitude under the same CAR.

a A comparison of the CAR values and the detected photon-pair rate among the photon-pair sources in previous literature and our work. Ref. 80 is visible-telecom source, and others are all-telecom sources. The sources based on SFWM, SPDC, and cascaded SHG/SPDC processes are represented by triangles, rectangles and circles, respectively. b A scheme of a fully integrated structure for generating high-performance correlated/entangled photon-pairs by using cascaded SHG and SPDC processes. A inner waveguide is inserted between the SHG and SPDC regions to remove the residual pump light at 1.5 μm. c Setup for the spectra measurement of SpRS noise photons and correlated photon-pairs. The PBS used in this setup is a cube, rather than a fiber-coupled one, in order to avoid the dependence of splitting ratio on wavelength. d, e The pump power dependence of the noise photons at signal and idler wavelengths, respectively. All the error bars are estimated by Poissonian photon-counting statistics. f A set of typical histograms of two-fold and three-fold coincidence counts obtained in the quantum-state tomography of time-bin entanglement.

Two main properties of entangled quantum light sources, integratability and high-performance on the combination of CAR and DPPR, are required in quantum photonics. The cascaded SHG/SPDC processes can avoid working with photons at quite different wavelengths, which is favorable in integrated devices. In this paper, we further propose a more integrated and high-performance scheme, as shown in Fig. 5b. It is a TFLN waveguide structure with two sections connected with a high-pass intermediate waveguide with cutoff wavelength of around 1 μm. The SHG and SPDC processes occur in the two sections before and after the intermediate waveguide, the cutoff property of which at 1.5 μm band can effectively remove the SpRS noise photons generated before the waveguide structure and prevent the 1.5 μm pump light from pumping SpRS process in the coupling fiber after the waveguide structure.

Methods

Preparation of double-pulsed pump light

The double-pulsed pump light used in the generation of time-bin entanglement is prepared by externally modulating the CW light which is generated from a narrow-linewidth semiconductor laser (PPCL550, PURE Photonics). We apply an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG, 70002A, Tektronix) to generate a pulsed electrical signal. In order to obtain optical pulses with high extinction ratio, the electrical signal is amplified to identical to the Vπ of the lithium niobite intensity modulator (IM, GC15MZPD7813, CETC-44) by a microwave amplifier (SHF Communication Technologies AG, SHF S126 A). A 99:1 BS combined with a photodetector is used to generate a feedback signal in a controller, ensuring the IM works under an optimal bias voltage. Furthermore, for the generation of time-bin entangled photon-pairs, we utilize the AWG to generate a double-pulsed electrical signal with repetition frequency, pulse interval, and single pulse width of 100 MHz, 625 ps, and 125 ps, respectively.

The spectra of noise and correlated photons

To evaluate the SpRS noise photons and correlated photon-pairs from the PPLN waveguide module, the spectra of them were recorded by photon counting. As shown in Fig. 5c, the PPLN waveguide module is pumped by a CW laser, and a PC combined with a PBS is used to select the co-polarized photon and the cross-polarized photon. A tunable filter (XTA-50/U, EXFO) is applied before a SNSPD to select photons with different frequencies for detection. The SPDC process in our PPLN waveguide satisfies type-0 phase matching, i.e., the photo-pairs created are co-polarized with the pump light. In contrast, the polarization of the SpRS noise photons distributes over all orientations, in which the co-polarized component is larger than the cross-polarized one82. Thus, we can approximately assume that the directions of polarization with the highest and lowest photon-counting rates are corresponding to the co-polarized photon and the cross-polarized photon, respectively. Under the phase-matching condition, we measure the spectrum of co-polarized photons by tuning the central wavelength of the tunable filter and give the result in Fig. 1b. Then, under the phase mismatching condition, we measure the spectra of co- and cross-polarized photons with the same pump power level, as shown in Fig. 1c, d, respectively. Figures 5d, e show the counting rates of co-polarized photons in signal and idler channels under different levels of pump power, respectively. The photon-counting rates versus pump power in both Fig. 5d, e can be fitted with linear functions. This indicates that the generation of correlated photon-pairs is suppressed under phase mismatching conditions. Thus, the spectra shown in Fig. 1c, d correspond to the co- and cross-polarized SpRS noise photons, respectively. Considering that the photon-counting rates in Fig. 1b are much larger than those in Fig. 1c, we approximately regard the result shown in Fig. 1b as the spectrum of the correlated photon-pairs.

Reconstruction of the frequency-bin entangled state

Using the method in Refs. 31 and78, we can reconstruct the density matrix of the frequency-bin entangled state from experimental measurements and the expression is

It is obvious that the off-diagonal elements in Eq. (4) are determined by V and φ obtained via Eq. (1). Here, the diagonal element α has a meaning of the ratio of the state |ωs〉|ωi〉 in the frequency-bin entangled state, and it can be estimated by measuring the counting rate of signal and idler photons from the UMZI. In our experiment, α = 0.502 ± 0.001 is obtained. The real and imaginary parts of the reconstructed density matrix are shown in Fig. 4b, c, respectively.

Quantum-state tomography of time-bin entanglement

With the theory given in Ref. 43, the projection measurements of a single time-bin qubit are implemented by passing through an UMZI with the time delay difference between the two arms equal to the time interval of time-bins. By injecting a time-bin qubit with state |ψ0〉 = α|1〉+β|2〉 (\(\left| \alpha \right|^2 + \left| \beta \right|^2 = 1\)) (|1〉 and |2〉 represent the qubit in early and late time-bins, respectively) into the UMZI and detecting photons from one output port of the UMZI, the photon could be observed possibly in three time slots. Photon detection at the first (third) slot corresponds to a projection of state onto|1〉 (|2〉), namely the “time basis”. Reversely, detection at the middle slot corresponds to a projection of state onto \((\left. {\left| 1 \right.} \right\rangle + e^{ - i\theta }\left. {\left| 2 \right.} \right\rangle )/\sqrt 2\), which is “energy basis” depending on the additional phase difference θ between the two arms.

In order to obtain the density matrix of the time-bin entangled photon-pairs, quantum-state tomography must be implemented by 16 combinations of projection measurements between different bases (|1〉, |2〉, |D〉, |R〉) for signal and idler photons, where \(\left. {\left| D \right.} \right\rangle = (\left. {\left| 1 \right.} \right\rangle + \left. {\left| 2 \right.} \right\rangle )/\sqrt 2\) and \(\left. {\left| R \right.} \right\rangle = (\left. {\left| 1 \right.} \right\rangle + i\left. {\left| 2 \right.} \right\rangle )/\sqrt 2\). Figure 5f shows some typical raw data in these projection measurements. When the additional phase differences α and β in the UMZIs in Fig. 2c are both set at 0, twofold coincidence between photons from the ports A1 and B1 in Fig. 2c are measured, and five distinguishable peaks appear in the coincidence histogram shown in Fig. 5f(i)72, which correspond to the projection on single basis or the sum of projections on different bases. The three middle peaks in the Fig. 5f(i) can further split into two or three peaks corresponding to the projection on single basis, when three-fold coincidence is implemented between the coincidence events in these peaks and the synchronous electrical signal, as shown in Fig. 5f(ii, iii, iv). As a consequence, we obtain the two-photon projection measurements on the following bases simultaneously: |11〉, |12〉, |1D〉, |21〉, |22〉, |2D〉, |D1〉, |D2〉, and |DD〉. In a similar way, we can perform the two-photon projection measurements on other bases by setting the α and β at 0&π/2, π/2&0, and π/2&π/2.

Data availability

All the data and calculations that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used to generate data will be made available to the interested reader upon reasonable request.

References

Jennewein, T., Simon, C., Weihs, G., Weinfurter, H. & Zeilinger, A. Quantum cryptography with entangled photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4729 (2000).

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145 (2002).

Lo, H. K., Curty, M. & Tamaki, K. Secure quantum key distribution. Nat. Photonics 8, 595–604 (2014).

Xu, F. H., Ma, X. F., Zhang, Q., Lo, H. K. & Pan, J. W. Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 025002 (2020).

Bouwmeester, D. et al. Experimental quantum teleportation. Nature 390, 575–579 (1997).

Valivarthi, R. et al. Quantum teleportation across a metropolitan fibre network. Nat. Photonics 10, 676–680 (2016).

Sun, Q. C. et al. Quantum teleportation with independent sources and prior entanglement distribution over a network. Nat. Photonics 10, 671–675 (2016).

Mitchell, M. W., Lundeen, J. S. & Steinberg, A. M. Super-resolving phase measurements with a multiphoton entangled state. Nature 429, 161–164 (2004).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Kok, P. et al. Linear optical quantum computing with photonic qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 135 (2007).

Carolan, J. et al. Variational quantum unsampling on a quantum photonic processor. Nat. Phys. 16, 322–327 (2020).

Stevenson, R. M. et al. A semiconductor source of triggered entangled photon pairs. Nature 439, 179–182 (2006).

Liu, J. et al. A solid-state source of strongly entangled photon-pairs with high brightness and indistinguishability. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 586–593 (2019).

Li, X. Y., Voss, P. L., Sharping, J. E. & Kumar, P. Optical-fiber source of polarization-entangled photons in the 1550 nm telecom band. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 053601 (2005).

Silverstone, J. W. et al. On-chip quantum interference between silicon photon-pair sources. Nat. Photonics 8, 104–108 (2014).

Lu, X. Y. et al. Heralding single photons from a high-Q silicon microdisk. Optica 3, 1331–1338 (2016).

Kues, M. et al. On-chip generation of high-dimensional entangled quantum states and their coherent control. Nature 546, 622–626 (2017).

Ma, Z. H. et al. Ultrabright quantum photon sources on chip. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 263602 (2020).

Malik, M. et al. Multi-photon entanglement in high dimensions. Nat. Photonics 10, 248–252 (2016).

Hong, C. K. & Mandel, L. Theory of parametric frequency down conversion of light. Phys. Rev. A 31, 2409 (1985).

Shih, Y. H., Sergienko, A. V., Rubin, M. H., Kiess, T. E. & Alley, C. O. Two-photon entanglement in type-II parametric down-conversion. Phys. Rev. A 50, 23 (1994).

Hübel, H. et al. Direct generation of photon triplets using cascaded photon-pair sources. Nature 466, 601–603 (2010).

Chen, L. X., Lei, J. J. & Romero, J. Quantum digital spiral imaging. Light Sci. Appl. 3, e153–e153 (2014).

Vergyris, P. et al. Two-photon phase-sensing with single-photon detection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 024001 (2020).

Llewellyn, D. et al. Chip-to-chip quantum teleportation and multi-photon entanglement in silicon. Nat. Phys. 16, 148–153 (2020).

Li, Y. H. et al. Multiuser time-energy entanglement swapping based on dense wavelength division multiplexed and sum-frequency generation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 250505 (2019).

Takesue, H. et al. Quantum teleportation over 100 km of fiber using highly efficient superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors. Optica 2, 832–835 (2015).

Ngah, L. A., Alibart, O., Labonté, L., D’Auria, V. & Tanzilli, S. Ultra‐fast heralded single photon source based on telecom technology. Laser Photonics Rev. 9, L1–L5 (2015).

Noh, T. G., Kim, H., Zyung, T. & Kim, J. Efficient source of high purity polarization-entangled photon pairs in the 1550 nm telecommunication band. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 011116 (2007).

Lutz, T., Piotr, K. & Thomas, J. Toward a downconversion source of positively spectrally correlated and decorrelated telecom photon pairs. Opt. Lett. 38, 697–699 (2013).

Ramelow, S., Ratschbacher, L., Fedrizzi, A., Langford, N. K. & Zeilinger, A. Discrete tunable color entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 253601 (2009).

Evans, P. G., Bennink, R. S., Grice, W. P., Humble, T. S. & Schaake, J. Bright source of spectrally uncorrelated polarization-entangled photons with nearly single-mode emission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 253601 (2010).

Eckstein, A., Christ, A., Mosley, P. J. & Silberhorn, C. Highly efficient single-pass source of pulsed single-mode twin beams of light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 013603 (2011).

Zhang, Q. et al. Correlated photon-pair generation in reverse-proton-exchange PPLN waveguides with integrated mode demultiplexer at 10 GHz clock. Opt. Express 15, 10288–10293 (2007).

Olislager, L. et al. Frequency-bin entangled photons. Phys. Rev. A 82, 013804 (2010).

Inagaki, T., Matsuda, N., Tadanaga, O., Asobe, M. & Takesue, H. Entanglement distribution over 300 km of fiber. Opt. Express 21, 23241–23249 (2013).

Bock, M., Lenhard, A., Chunnilall, C. & Becher, C. Highly efficient heralded single-photon source for telecom wavelengths based on a PPLN waveguide. Opt. Express 24, 23992–24001 (2016).

Zhao, J., Ma, C. X., Rüsing, M. & Mookherjea, S. High quality entangled photon pair generation in periodically poled thin-film lithium niobate waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 163603 (2020).

Zhu, E. Y. et al. Poled-fiber source of broadband polarization-entangled photon pairs. Opt. Lett. 38, 4397–4400 (2013).

Guo, X. et al. Parametric down-conversion photon-pair source on a nanophotonic chip. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e16249–e16249 (2017).

Fan, J., Eisaman, M. D. & Migdall, A. Bright phase-stable broadband fiber-based source of polarization-entangled photon pairs. Phys. Rev. A 76, 043836 (2007).

Dyer, S. D., Baek, B. & Nam, S. W. High-brightness, low-noise, all-fiber photon-pair source. Opt. Express 17, 10290–10297 (2009).

Takesue, H. & Noguchi, Y. Implementation of quantum state tomography for time-bin entangled photon-pairs. Opt. Express 17, 10976–10989 (2009).

Li, X. Y. et al. All-fiber source of frequency-entangled photon-pairs. Phys. Rev. A 79, 033817 (2009).

Zhou, Q. et al. Frequency-entanglement preparation based on the coherent manipulation of frequency nondegenerate energy-time entangled state. J. Optical Soc. Am. B 31, 1801–1806 (2014).

Davanco, M. et al. Telecommunications-band heralded single photons from a silicon nanophotonic chip. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 261104 (2012).

Engin, E. et al. Photon pair generation in a silicon micro-ring resonator with reverse bias enhancement. Opt. Express 21, 27826–27834 (2013).

Xiong, C. L. et al. Bidirectional multiplexing of heralded single photons from a silicon chip. Opt. Lett. 38, 5176–5179 (2013).

Harris, N. C. et al. Integrated source of spectrally filtered correlated photons for large-scale quantum photonic systems. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041047 (2014).

Wakabayashi, R. et al. Time-bin entangled photon pair generation from Si micro-ring resonator. Opt. Express 23, 1103–1113 (2015).

Grassani, D. et al. Micrometer-scale integrated silicon source of time-energy entangled photons. Optica 2, 88–94 (2015).

Jiang, W. C. et al. Silicon-chip source of bright photon pairs. Opt. Express 23, 20884–20904 (2015).

Savanier, M., Kumar, R. & Mookherjea, S. Optimizing photon-pair generation electronically using a pin diode incorporated in a silicon microring resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 131101 (2015).

Mazeas, F. et al. High-quality photonic entanglement for wavelength-multiplexed quantum communication based on a silicon chip. Opt. Express 24, 28731–28738 (2016).

Ma, C. X. et al. Silicon photonic entangled photon-pair and heralded single photon generation with CAR> 12,000 and g(2)(0)< 0.006. Opt. Express 25, 32995–33006 (2017).

Feng, L. T. et al. On-chip transverse-mode entangled photon pair source. npj Quant. Inf. 5, 1–7 (2019).

Shi, X. D. et al. Multichannel photon-pair generation with strong and uniform spectral correlation in a silicon microring resonator. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 034053 (2019).

Oser, D. et al. High-quality photonic entanglement out of a stand-alone silicon chip. npj Quant. Inf. 6, 1–6 (2020).

Starling, D. J. et al. Nonlinear photon pair generation in a highly dispersive medium. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 041005 (2020).

Paesani, S. et al. Near-ideal spontaneous photon sources in silicon quantum photonics. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–6 (2020).

Xiong, C. L. et al. Compact and reconfigurable silicon nitride time-bin entanglement circuit. Optica 2, 724–727 (2015).

Samara, F. et al. High-rate photon pairs and sequential time-bin entanglement with Si3N4 microring resonators. Opt. Express 27, 19309–19318 (2019).

Xiong, C. L. et al. Generation of correlated photon pairs in a chalcogenide As2S3 waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 051101 (2011).

Reimer, C. et al. Generation of multiphoton entangled quantum states by means of integrated frequency combs. Science 351, 1176–1180 (2016).

Spring, J. B. et al. Chip-based array of near-identical, pure, heralded single-photon sources. Optica 4, 90–96 (2017).

Steiner, T. J. et al. Ultrabright entangled-photon-pair generation from an AlGaAs-On-insulator microring resonator. PRX Quantum 2, 010337 (2021).

Arahira, S., Namekata, N., Kishimoto, T. & Inoue, S. Experimental studies in generation of high-purity photon-pairs using cascaded χ(2) processes in a periodically poled LiNbO3 ridge-waveguide device. J. Optical Soc. Am. B 29, 434–442 (2012).

Hunault, M., Takesue, H., Tadanaga, O., Nishida, Y. & Asobe, M. Generation of time-bin entangled photon-pairs by cascaded second-order nonlinearity in a single periodically poled LiNbO3 waveguide. Opt. Lett. 35, 1239–1241 (2010).

Arahira, S., Namekata, N., Kishimoto, T., Yaegashi, H. & Inoue, S. Generation of polarization entangled photon-pairs at telecommunication wavelength using cascaded χ(2) processes in a periodically poled LiNbO3 ridge waveguide. Opt. Express 19, 16032–16043 (2011).

Massaro, M., Meyer-Scott, E., Montaut, N., Herrmann, H. & Silberhorn, C. Improving SPDC single-photon sources via extended heralding and feed-forward control. N. J. Phys. 21, 053038 (2019).

Franson, J. D. Bell inequality for position and time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2205 (1989).

Marcikic, I. et al. Distribution of time-bin entangled qubits over 50 km of optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 180502 (2004).

James, D. F. V., Kwiat, P. G., Munro, W. J. & White, A. G. Measurement of qubits. Phys. Rev. A 64, 052312 (2001).

Tittel, W., Brendel, J., Gisin, N. & Zbinden, H. Long-distance Bell-type tests using energy-time entangled photons. Phys. Rev. A 59, 4150 (1999).

Ali-Khan, I., Broadbent, C. J. & Howell, J. C. Large-alphabet quantum key distribution using energy-time entangled bipartite states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 060503 (2007).

Lefebvre, P. et al. Compact energy–time entanglement source using cascaded nonlinear interactions. J. Optical Soc. Am. B 38, 1380–1385 (2021).

Imany, P. et al. High-dimensional optical quantum logic in large operational spaces. npj Quant. Inf. 5, 1–10 (2019).

Kaneda, F., Suzuki, H., Shimizu, R. & Edamatsu, K. Direct generation of frequency-bin entangled photons via two-period quasi-phase-matched parametric down conversion. Opt. Express 27, 1416–1424 (2019).

Xie, Z. D. et al. Harnessing high-dimensional hyperentanglement through a biphoton frequency comb. Nat. Photonics 9, 536–542 (2015).

Lu, X. Y. et al. Chip-integrated visible–telecom entangled photon-pair source for quantum communication. Nat. Phys. 15, 373–381 (2019).

Chen, J. Y. et al. Efficient parametric frequency conversion in lithium niobate nanophotonic chips. OSA Contin. 2, 2914–2924 (2019).

Li, X. Y., Voss, P. L., Chen, J., Lee, K. F. & Kumar, P. Measurement of co-and cross-polarized Raman spectra in silica fiber for small detunings. Opt. Express 13, 2236–2244 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Z.Z. Wang and Mr. Q.Z. Cai for the helpful discussions. This work is partially supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2018YFA0307400, 2019YFB2203400, 2017YFA0304000, 2018YFA0306102, and 2017YFB0405100); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 61775025, 62075034, 12074058, 91836102, U19A2076, 61405030, 61704164, and 62005039); Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2018JY0084); Open-Foundation of Key Laboratory of Laser Device Technology, China North Industries Group Corporation Limited (KLLDT202008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. convinced and supervised the project. Z.Z. and H.Y. under the supervision of Q.Z. and Z.W, and C.Y. under the supervision of G.G. performed the experiment and data analysis. S.S. and R.Z. under the supervision of H.S. and Y.W. developed the feedback system for generating pulsed pump light and the temperature control system for the PPLN module. H.W., H.L., L.Y., and Z.W. developed and maintained the SNSPDs used in the experiment. All authors participated in discussions of the results. Q.Z., Z.Z., and C.Y. prepared the manuscript with assistance from all other co-authors. All authors have given approval for the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Yuan, C., Shen, S. et al. High-performance quantum entanglement generation via cascaded second-order nonlinear processes. npj Quantum Inf 7, 123 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00462-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00462-7

This article is cited by

-

Quantum storage of 1650 modes of single photons at telecom wavelength

npj Quantum Information (2024)

-

Photonic-chip-based dense entanglement distribution

PhotoniX (2023)

-

Hertz-rate metropolitan quantum teleportation

Light: Science & Applications (2023)