Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objectives:

The aim of this report was to describe an example of pulmonary embolism (PE), recently suggested to be highly prevalent in persons with chronic spinal cord lesions.

Setting:

Veterans Affairs Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Methods:

Chart review.

Results:

A 60-year-old man with paraplegia, T10 motor complete, underwent laminectomy for correction of an arteriovenous malformation. After 41 days, he sustained a massive PE—suggested by right bundle branch block (RBBB) on an electrocardiogram (ECG) and diagnosed by perfusion lung scanning. He was treated with anticoagulants, the lung scan and RBBB resolving within 1 month of initiating treatment. After 5 years, he developed vertebral osteomyelitis at L5-S1 and was treated with antibiotics and bed rest. After 7 days, he was mobilized to a wheelchair, and during a transfer back to bed, he developed anxiety, dyspnea, fluctuating consciousness, low blood pressure and RBBB, absent by ECG 4 days earlier. He expired 20 min after onset of symptoms. The autopsy revealed a fresh thromboembolus occluding both main stem branches of the pulmonary artery.

Conclusion:

Massive PE after surgery in a patient with chronic paraplegia recurred 5 years later in association with severe infection and mobilization after bed rest, which resulted in death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persons with spinal cord lesions (SCLs) are widely known to be at risk for fatal pulmonary embolism (PE) immediately after paralysis; however, chronic, fatal PE has only recently been described.1 The PE in the chronic SCL population can be insidious or acute and catastrophic. An example of the latter is described.

Case report

A 64-year-old man had sustained progressive loss of sensation, ability to walk, and bowel and bladder control over a 4-year period. A clinical exam revealed complete motor and sensory deficit at T10. A laminectomy at L1 and 2 was carried out to ablate an arteriovenous malformation revealed by angiography.

After 41 days of surgery, the patient had not displayed any neurological recovery and developed shortness of breath during a physical therapy session. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed a new right bundle branch block (RBBB), and an echocardiogram showed an embolus within the right side of the heart. In addition, a defect in the left lower lobe was present in a perfusion lung scan, and a deep venous thrombosis was identified in the right lower extremity using compression ultrasound. The patient was immediately treated with heparin and then shifted to coumadin for 6 months, although the lung scan resolved and the RBBB disappeared at 1 month.

The patient was hospitalized 5 years later at age 69 years for a febrile illness but died by cardiovascular collapse 7 days after admission (Table 1). On that day, having been treated with antibiotics and extended bed rest, the patient was mobilized to a wheelchair wearing an elastic girdle for lumbar support. Although he was being transferred back to bed with a hydraulic lift, the patient developed anxiety and shortness of breath, followed by fluctuating levels of blood pressure and consciousness. He denied chest pain. An ECG revealed a recurrence of RBBB. Heparin was administered by i.v. bolus. He lost all consciousness 20 min after the onset of this event and expired despite attempts at resuscitation.

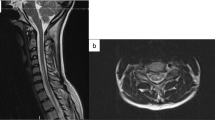

An autopsy revealed a massive PE at the bifurcation of the pulmonary artery (Figure 1), which originated in a lower extremity proximal venous system (Figure 2). No studies of coagulopathy had been carried out before death. A paravertebral abscess was found at L5-S1. The spinal cord exam revealed fibroglial scarring with abnormal vasculature of the thoracic cord, no inflammation.

Discussion

This case study illustrates examples of nonfatal and fatal PE events in a person with paraplegia that occurred well after the widely known high-risk period immediately after an SCL.

Using an electrocardiographic survey for RBBB, a recent study1 found that PE in patients with chronic SCL is not rare and its prevalence of 14% at death by clinical review is comparable to the 14.6% prevalence by autopsy examination in an able-bodied population.2 Although the PE found in that study was chiefly small and recurrent and clinically silent, resulting eventually in pulmonary hypertension and RBBB; some PE was massive and the immediate cause of death, as described here. The authors believe that the incidence of death due to PE in the chronic SCL population exceeds that of the general population, although solid evidence for this is lacking.

Although the etiology of recurrent PE long after paralysis is not clear, factors leading to the fatal PE in this case report can be considered. First, the preceding PE is a well-recognized risk factor, possibly representing a state of hypercoagulability in this patient.3 Regrettably, a coagulopathy workup was not carried out. Second, severe infection with tissue damage, as is prevalent with SCL, can lead to fatal PE.4 Third, bed rest can be suggested by some; but this factor seems unlikely since venous stasis is chronic due to the paralysis of the lower limbs.

PE prevention in persons with myelopathy through the use of anticoagulation is complicated by delays in wound healing.5 However, in the event of infection and/or hypercoagulability, prophylaxis with anticoagulation might be considered in patients with chronic SCL. A need exists for the assessment of coagulopathy in high-risk scenarios as presented or in cases of thromboembolic events after the high-risk period after an SCL. Elastic stockings in high-risk conditions, such as infections, can be recommended as useful and safe adjuncts.

It is concluded that PE occurs in persons with chronic paralysis caused by SCLs and can be fatal. Furthermore, RBBB identified through an ECG may be useful in indicating the occurrence or recurrence of PE in such persons.

References

Frisbie JH, Sharma GVRK . Right bundle branch block as a screening test for pulmonary embolism chronic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 1241–1244.

Stein PD, Henry JW . Prevalence of acute pulmonary embolism among patients in a general hospital and at autopsy. Chest 1995; 108: 978–981.

Kraus JA, Stuper BK, Berlit P . Association of resistance to activated protein C and dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Neurol 1998; 245: 731–733.

Garlund B . Randomized, controlled trial of low-dose heparin for prevention of fatal pulmonary embolism in patients with infectious diseases. The heparin prophylaxis study group. Lancet 1996; 347: 1357–1361.

Frisbie JH . Wound healing in acute spinal cord injury: effect of anticoagulation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986; 67: 311–313.

Acknowledgements

This case study was possible through the resources and facilities at the VA Boston Hospital in Boston, MA, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frisbie, J., Sharma, G. Recurrent, massive pulmonary embolism in chronic myelopathy: a case report. Spinal Cord 49, 318–320 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.54

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.54