Abstract

Understanding the characteristics of a quantum systems when affected by noise is one of the biggest challenges for quantum technologies. The general Pauli error channel is an important lossless channel for quantum communication. In this work we consider the effects of a Pauli channel on a pure four-qubit state and simulate the Pauli channel experimentally by studying the action on polarization encoded entangled photons. When the noise channel acting on the photons is correlated, a set spanned by four orthogonal bound entangled states can be generated. We study this interesting case experimentally and demonstrate that products of Bell states can be brought into a bound entangled regime. We find states in the set of bound entangled states which experimentally violate the CHSH inequality while still possessing a positive partial transpose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coherent superpositions and entanglement are key resources in quantum communication and computation tasks. Quantum methods and techniques rely on the preparation, transmission, processing and detection of quantum states. But quantum states are very fragile and easily destroyed by decoherence processes due to unwanted coupling with the environment. These uncontrollable influences cause noise in the communication or errors in the outcome of a computation and thus reduce the advantages of quantum information resources. To overcome the decoherence problem, several purification and distillation protocols have been proposed and implemented, each of them appropriate for a specific type of coupling with the environment1,2,3,4,5,6,7. These protocols use local operations assisted by classical communications (LOCC). In most protocols the parties involved are distributed in separated locations, local operations is then a natural restriction since the parties involved can coordinated by classical communication the operations they will do on their own qubits. It has been shown that there is a class of noisy non-separable quantum states where no entanglement can be distilled. This entanglement class has been termed bound entanglement (BE)8. These BE states live in the “gray” area between the separable (classical) and distillable non-separable (free entangled) states. One way to create such an irreversible noisy state is to start with a pure entangled state and then subject it to stochastic local actions which bring the state into the BE regime. These stochastic local actions can be modelled by an LOCC action and is considered to occur during the transmission of the qubits to the parties. In order to detect BE, one can use the positive partial transpose (PT) method9 combined with an entanglement indicator such as the witness method. Even though BE is regarded as a weak form of entanglement, it has been shown that some BE states can maximally violate the CHSH inequality10,11. Thus there is no hidden variable model that can be assigned to such states. Moreover, it has been shown that BE can be used as a resource in quantum communication tasks such as secret sharing, key distribution12, superactivation13 and super-additivity of channel capacity14.

BE has been demonstrated experimentally only very recently15,16,17,18,19. In all these experiments, a large amount of depolarized noise was added to reach the BE regime, which prevented a violation of the CHSH inequality. From the perspective of quantum communication applications the violation of a Bell inequality is closely related to the reduction of communication complexity20. Further experimental investigations are therefore needed to understand how noise affects quantum states and how BE-states are generated. Our objective is thus to identify those situations when the distributed states are in a BE-regime that is useful for quantum communication. In this work we focus on highly symmetric four-qubit BE states which are generated through a Pauli channel21,22,23.

Results

Modelling the pauli quantum channel

Here we consider a lossless decoherence channel induced by an environment when pure entangled states are to be distributed. Suppose four separated parties Alice (A), Bob (B), Charlie (C) and David (D) like to share two pure bipartite entangled states among each other. The state considered here is two-Bell-state-like,

where  is shared between Alice and Bob and

is shared between Alice and Bob and  is shared between Charlie and David. If the four parties want to use this state for any type of quantum communication task such as teleportation, they may run into problems due to the errors introduced during the distribution process. These errors can be considered as decoherence induced by an environment. In our model, each qubit is affected in the transmission by a general noise that is constructed by a random bit flip and/or phase flip. These can be represented mathematically by the Pauli spin operators, σx and σz, respectively and σy, when both errors occur. By applying these operators to | Ψ− 〉 one can convert the state to any other Bell state,

is shared between Charlie and David. If the four parties want to use this state for any type of quantum communication task such as teleportation, they may run into problems due to the errors introduced during the distribution process. These errors can be considered as decoherence induced by an environment. In our model, each qubit is affected in the transmission by a general noise that is constructed by a random bit flip and/or phase flip. These can be represented mathematically by the Pauli spin operators, σx and σz, respectively and σy, when both errors occur. By applying these operators to | Ψ− 〉 one can convert the state to any other Bell state,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  , where

, where  denotes the unity matrix. The noise can in principle affect any of the two qubits, but the result is the same, regardless of which of the two qubits is affected. Thus we can theoretically model the noise as affecting only one of the qubits of | Ψ− 〉. A general decoherence channel for a bit- and phase-flip error on the four qubits of ρ can be represented by

denotes the unity matrix. The noise can in principle affect any of the two qubits, but the result is the same, regardless of which of the two qubits is affected. Thus we can theoretically model the noise as affecting only one of the qubits of | Ψ− 〉. A general decoherence channel for a bit- and phase-flip error on the four qubits of ρ can be represented by

where A, B, C, D are the four parties,  , with

, with  , is one of the error operators acting on the qubits of parties k and l and pij is the probability that the error operation

, is one of the error operators acting on the qubits of parties k and l and pij is the probability that the error operation  will occur on the state ρ. Furthermore, the sum over all pij is normalized to 1. Note that since all states under consideration stem from the seed (1) which is manipulated by local errors through the channel (2), there will always be a separable cut between AB and CD. The noise channel (2) acting on (1) can generate three categories of quantum states: (a) states with free entanglement which can be subjected to a distillation scheme to distill entangled pure states, (b) separable mixed states such as the maximally mixed state and (c) BE states, which we will study here.

will occur on the state ρ. Furthermore, the sum over all pij is normalized to 1. Note that since all states under consideration stem from the seed (1) which is manipulated by local errors through the channel (2), there will always be a separable cut between AB and CD. The noise channel (2) acting on (1) can generate three categories of quantum states: (a) states with free entanglement which can be subjected to a distillation scheme to distill entangled pure states, (b) separable mixed states such as the maximally mixed state and (c) BE states, which we will study here.

There are four highly symmetrical choices of pij that are of special interest, namely pij = 1/4 for  or

or  or

or  or

or  . Together, these four sets represent all possible combinations of i and j. The four-qubit states that are generated by the four sets Γi when the pure state (1) is transmitted through the channel can be represented in a simple fashion by the action of the Pauli spin operators:

. Together, these four sets represent all possible combinations of i and j. The four-qubit states that are generated by the four sets Γi when the pure state (1) is transmitted through the channel can be represented in a simple fashion by the action of the Pauli spin operators:

The first state, ρ1, is the BE Smolin21 state. The other three states, (4), (5) and (6), can be obtained from the Smolin state by rotating one of its qubits by σy, σz and σx, respectively. Since these are only local rotations all ρi are BE (see supplementary material).

Note that (3)–(6) have properties that are similar to the four maximally entangled two-qubit Bell states23,24. They are all mutually orthogonal, (Tr(ρi · ρj) = δij/4). Furthermore, when depolarizing noise (which is a special case of the Pauli channel (2) generated by blending the four sets Γi) of the form

with i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}, is added, we find that they have the same tolerance for breaking a CHSH inequality  and the same condition for separability, namely p ≥ 2/3. Moreover, the CHSH violation is maximal when p = 0. However, it is not possible to quantum-teleport information with these states alone when restricted to LOCC between the parties.

and the same condition for separability, namely p ≥ 2/3. Moreover, the CHSH violation is maximal when p = 0. However, it is not possible to quantum-teleport information with these states alone when restricted to LOCC between the parties.

We like to investigate the set of quantum states spanned by the four ρi or equivalently by the four sets Γi applied on (1). All states in this set are mixtures of the four bound entangled states ρi, which are generated by adding constraints to the pij in the noise channel (2). This can be represented by,

where ωi with i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4} is the probability of obtaining ρi, with  . Note that choosing all ωi = 1/4 results in the completely mixed state.

. Note that choosing all ωi = 1/4 results in the completely mixed state.

Analogous to the graphical illustration of the Bell diagonal states23,24, the set of states (8) can be depicted as a probability tetrahedron as illustrated in Fig. 1. The coordinates of the states situated inside the tetrahedron are related to (3)–(6) by, xcor = ω1 − ω2 − ω3 + ω4, ycor = ω1 + ω2 − ω3 − ω4, zcor = ω1 − ω2 + ω3 − ω4. The corner vertices represent (3)–(6) and it can be shown23 that they are the purest states in the set by observing that  . In contrast to the set spanned by the Bell diagonal states which includes maximally entangled and separable states, the considered four-qubit set only contains states with a positive PT for any bipartite cut between pairs (any 2:2 cut).

. In contrast to the set spanned by the Bell diagonal states which includes maximally entangled and separable states, the considered four-qubit set only contains states with a positive PT for any bipartite cut between pairs (any 2:2 cut).

The set spanned by the four bound entangled states ρi can be represented by a tetrahedron.

The corners represent the four bound entangled states (3)–(6). An edge connecting two vertices, for instance ρi and ρj, can be described by states of the form ρ(p) = p · ρi + (1 − p)·pj with 0 ≤ p ≤ 1. The planes depict the boundary between separable states that are contained in the octahedron and BE states. The planes are constructed via the four witnesses (9) which restrict the ωi in (8).

To show that the BE state is entangled and not separable across cuts of the form A|BCD, C|ABD, etc and A|B|CD, C|A|BD, etc, we use the entanglement witness method derived in15,19,25,

where i ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4} are the four BE states (3)–(6). Each witness generates a plane that cuts the tetrahedron in Fig. 1, dividing the separable from the BE states. The planes and the boundaries of the tetrahedron form an octahedron that contains separable states.

As it turns out, one can construct a simple four-setting CHSH inequality that is maximally violated by the four bound entangled states11,22. The inequality can be restated in a more general form,

where B is the Bell operator defined by:

where  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are vectors of unit length in

are vectors of unit length in  and

and  is a vector composed by the three Pauli operators. The maximal violation can be obtained for the BE states ρi when measuring the four observables corresponding to

is a vector composed by the three Pauli operators. The maximal violation can be obtained for the BE states ρi when measuring the four observables corresponding to  and

and  . Achieving a violation of the CHSH inequality for a BE state experimentally is highly demanding. Aside from a value larger than 2 in (10), a positive PT needs to be obtained as well. The smallest possible PT value for a maximal violation of the CHSH inequality has a value of 0. One can increase this value by adding depolarized noise at the expense of decreasing the amount of violation of the CHSH inequality (see supplementary material). The smallest PT value corresponding to the boundary of the CHSH inequality is only

. Achieving a violation of the CHSH inequality for a BE state experimentally is highly demanding. Aside from a value larger than 2 in (10), a positive PT needs to be obtained as well. The smallest possible PT value for a maximal violation of the CHSH inequality has a value of 0. One can increase this value by adding depolarized noise at the expense of decreasing the amount of violation of the CHSH inequality (see supplementary material). The smallest PT value corresponding to the boundary of the CHSH inequality is only  .

.

Experimental results

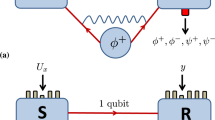

A double-pass spontaneous parametric down conversion source with motorized polarization optic was used to realise the seed state (1) and the Pauli quantum channel (2) respectively, see Fig. 2. For details about the experimental procedure see the Method section. The experimental results in Fig. 3 show the generation of one of the four corner vertex states of the tetrahedron and of the mixtures of these “corner states”. The mixture under consideration correspond to states with depolarization noise, (7). The added noise enables us to probe the regime illustrated by the dotted lines in Fig. 1, thus moving inwards towards the center of the tetrahedron with increasing amount of noise. All density matrices represented by the data points are obtained directly from the experimental data set by extracting the statistics of interest through the settings-tags in the data, see method section for details of the experimental procedure. The x-axis in Fig. 3 is the induced noise parameter representing (p) in the depolarized state, (7).

The experimental setup of the double-pass spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC).

A BBO crystal is pumped twice with UV pulses creating four pairwise entangled photons. The noisy channel is marked as environment D(ρ) in the figure. The bit flip and the phase shift to generate a mixture of Bell states are implemented by rotating a motorized half-wave plate (M-HWP) and tilting a motorized birefringent glass plate (M-PS). To achieve the desired probability, the settings of these optical components are controlled by a computer. Single mode fibers (SMF) are used to couple the photons. These are brought to local polarization analyzers which are followed by single photon detectors (APD).

Experimental data for depolarizing four-qubit state ρ3, representing one of the corners of the tetrahedron in Fig. 1.

The experimental data with their fits corresponds to, the CHSH value (light blue bar), smallest 2:2 PT (blue bar), smallest 1:3 PT (red bar) and the entanglement witness (green bar), versus the amount of depolarizing noise, p in (7). Specifically, we observe that the boundary of the violation of the CHSH inequality is close to where the PT switches to a positive value. See supplementary material for the values with errors and similar plots of the other three states, ρ1, ρ2 and ρ4.

We can observe the following along the evolution of the state ρ3 (see supplementary material for the other three states): At first, zero depolarizing noise, the state contain a small amount of free entanglement (smallest PT value over all 2:2 cuts is less the 0) and the violation of the CHSH inequality is high. The Bell inequality is tested by evaluating the expectation value of Bell operator (eq. 11) for each experimentally reconstrcted four-qubit density matrices. Adding more depolarized noise increases the smallest PT value while decreasing the CHSH violation. In the gray-shaded zone we have genuine bound entanglement where the witness and the smallest PT value over the cuts 1:3 is negative whiles the smallest PT value over the three 2:2 cuts is positive. The BE regime ends when the witness and smallest PT value over the cuts 1:3 is positive, which is where the separable states begin to emerge. To emphasize the trend in the data we perform a linear fits to the data.

Aside from the decoherence channel introduced by hand there are other sources of error due to experimental imperfections. Thus the introduced noise statistics suggested by theory might not be the best choice of noise for generating positive PT entangled states experimentally. By using all sixteen pij in (2) to generate other statistical distributions we are able to find BE states which do violate the CHSH inequality. To observe BE states with CHSH inequality violation, we use an optimization method that goes as a follows. As a starting point we used the experimental state corresponding to p = 0.15. To it we add a small random fluctuation on all pij to disturb the state slightly. For each perturbed state we reconstructed the density matrix and calculated all PT over all 2:2 cuts and the CHSH value. After several runs we picked a new seed state, from the previously generated set, which has higher 2:2 PT value and higher CHSH violation value. This procedure is repeated several times until no improvement is observed in the two values. For states close to any of the four BE states ρ1, ρ2, ρ3 and ρ4 we can find states that do have a positive PT value for all 2:2 cuts and do violate the CHSH inequality. In Fig. 4, we show a sub set of the states generated in the optimization process which are close to ρ3. In this set we have obtained a violation up to 2.0237 ± 0.0072 with a value of 0.0032 ± 0.0014 for the smallest PT over all three 2:2 bipartite cuts. The density matrix corresponding to this state is shown in Fig. 4. Since it is close to ρ3, its anti-diagonal is negative. Also note the small amount of noise added to the diagonal. In the supplementary material we show similar plots to Fig. 4 of the generated states for the other cases, ρ1, ρ2 and ρ4.

Experimental data when optimizing the PT 2:2 and CHSH violation values by adding a small random fluctuation to the existing noise parameter.

On the x-axes is the smallest PT value over all 2:2 cuts and on the y-axis is the CHSH value. Each point in the plot correspond to a state close to ρ3 with an added small random perturbation on all sixteen pij in (2). After the simple optimization we were able to enter the region where a Bell violation can be observed together with a positive eigenvalue of the smallest 2:2 PT value. For the more interesting states we calculated the error of both quantities (blue bars in the plots). As seen we find states that are fully immersed in the region of interest. Folded in is the real part of the experimental density matrix for one BE state close to the p = 0.15 that violates the CHSH inequality. This state has a CHSH value of 2.0237 ± 0.0072 and a value of 0.0032 ± 0.0014 for the smallest PT over all tree 2:2 bipartite cuts.

Discussion

We have experimentally investigated the characteristics of an entangled state in a bit-flip and phase-flip lossless error quantum channel. This noisy channel can generate a set of bound entangled states that violates a CHSH inequality when a product of Bell states is sent through it. We were able to experimentally investigate the boundary regime between free entangled, BE and separable states. By optimizing all sixteen pij in (2) and the settings of the CHSH measurement we find states which do violate the CHSH inequality, example is the value of 2.0237 ± 0.0072 for the folded in density matrix in Fig. 3, while still having a positive partial transpose, the smallest PT over all 2:2 cut is 0.0032 ± 0.0014 for the density matrix in Fig. 3 (See supplementary material for plots of the the of states analysed). We believe that our experimental methods and results open the possibility to experimentally investigate more complex entanglement structures and simulate other quantum channels and their quantum communication and cryptography applications.

Methods

Experimental procedure

Our qubits are encoded experimentally in the single-photon polarization degree of freedom with the basis states |H 〉 = | 0 〉, | V 〉 = | 1 〉. We produce products of two Bell states through doublepass spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC). A 2 mm long Type-II β-barium borate (BBO) crystal is pumped with 390 nm UV-pulses in the configuration shown in Fig. 2. We experimentally realized the sixteen operators  for the simulation of the decoherence channel. The bit- and phase-flip operation are implemented by rotating half-wave plates (HWP) from 0° to 45° and by tilting birefringent glass plates (PS), respectively. The probabilities pij of the Pauli channel D(ρ) are given by the probabilities of the settings of the half wave plate and the birefringent media for each pair. To generate a probability distribution for the noise we mount the half-wave plate (M-HWP) and birefringent glass (M-PS) on motorized rotation and tilting mounts, respectively (see Fig. 2). These motors are controlled by a computer that randomly configures the settings according to the desired probability distribution. In order to obtain good control over the experiment, we run the experiment with a probability distribution with equal weights for all settings. All noise settings, i and j in

for the simulation of the decoherence channel. The bit- and phase-flip operation are implemented by rotating half-wave plates (HWP) from 0° to 45° and by tilting birefringent glass plates (PS), respectively. The probabilities pij of the Pauli channel D(ρ) are given by the probabilities of the settings of the half wave plate and the birefringent media for each pair. To generate a probability distribution for the noise we mount the half-wave plate (M-HWP) and birefringent glass (M-PS) on motorized rotation and tilting mounts, respectively (see Fig. 2). These motors are controlled by a computer that randomly configures the settings according to the desired probability distribution. In order to obtain good control over the experiment, we run the experiment with a probability distribution with equal weights for all settings. All noise settings, i and j in  , are registered together with the photon counts for the 81 measurement settings required for an over-complete quantum state tomography (see supplementary material for details on the reconstruction). Each party uses a polarization analyser that consists of a 3 nm filter followed by half- and quarter-wave plates (HWP and QWP, respectively) and a polarization beam splitter (PBS). The photons are detected by avalanche photo diodes (APD). We implement all possible combinations of projections on the eigenstates of the three Pauli spin matrices in the measurement settings and each measurement setting is measured for 4 hours. We obtain a four-photon rate of about 1 four-fold coincidence per second and the introduced noise is set to shift with a speed of 1 Hz. With this approach we can analyze any mixture that can be produced by the source and with any type of bit and phase flip error. We employ a maximum likelihood technique for the reconstruction of the density matrices and the errors are evaluated by a Monte Carlo simulation over the counting statistics of the experimental data.

, are registered together with the photon counts for the 81 measurement settings required for an over-complete quantum state tomography (see supplementary material for details on the reconstruction). Each party uses a polarization analyser that consists of a 3 nm filter followed by half- and quarter-wave plates (HWP and QWP, respectively) and a polarization beam splitter (PBS). The photons are detected by avalanche photo diodes (APD). We implement all possible combinations of projections on the eigenstates of the three Pauli spin matrices in the measurement settings and each measurement setting is measured for 4 hours. We obtain a four-photon rate of about 1 four-fold coincidence per second and the introduced noise is set to shift with a speed of 1 Hz. With this approach we can analyze any mixture that can be produced by the source and with any type of bit and phase flip error. We employ a maximum likelihood technique for the reconstruction of the density matrices and the errors are evaluated by a Monte Carlo simulation over the counting statistics of the experimental data.

References

Bennett, C. H., Bernstein, H. J., Popescu, S. & Schumacher, B. Concentrating partial entanglement by local operations. Phys. Rev. A 53, 2046 (1996).

Bennett, C. H., DiVincenzo, D. P., Smolin, J. A. & Wootters, W. K. Mixed-state entanglement and quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. A 54, 3824 (1996).

Bennett, C. H., Brassard, G., Popescu, S., Schumacher, B., Smolin, J. A. & Wootters, W. K. Purifcation of noisy entanglement and faithful teleportation via noisy channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 722 (1996).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Inseparable two spin- 1/2 density matrices can be distilled to a singlet form. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 574 (1997).

Opatrný, T. & Kurizki, G. Optimization approach to entanglement distillation. Phys. Rev. A 60, 167 (1999).

Bose, S., Vedral, V. & Knight, P. L. Purifcation via entanglement swapping and conserved entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 60, 194 (1999).

Kwiat, P. G., Barraza-Lopez, S., Stefanov, A. & Gisin, N. Experimental entanglement distillation and ‘hidden’ non-locality. Nature. 409, 1014–1017 (2001).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Mixed-State Entanglement and Distillation: Is there a Bound Entanglement in Nature? Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5239 (1998).

Peres, A. Separability Criterion for Density Matrices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 14131415 (1996).

Dür, W. Multipartite Bound Entangled State that Violate Bell's Inequality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 230402 (2001).

Augusiak, R. & Horodecki, P. Bound entanglement maximally violating Bell inequalites:Quantum entanglement is not fully equivalent to cryptographic security. Phys. Rev. A 74, 010305 (2006).

Horodecki, K., Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Oppenheim, J. Secure Key from Bound Entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 160502 (2005).

Shor, P. W., Smolin, J. A. & Thapliyal, A. V. Superactivation of Bound Entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 107901 (2003).

Smith, G. & Yard, J. Quantum communication with zero capacity channels. Science 321, 1812 (2008).

Amselem, E. & Bourennane, M. Experimental four-qubit bound entanglement. Nature Phys. 5, 748 (2009).

Amselem, E. & Bourennane, M. Reply to ‘Experimental bound entanglement?’. Nature Phys. 6, 827 (2010).

Barreiro, J. T., Schindler, P., Gühne, O., Monz, T., Chwalla, M., Roos, C. F., Hennrich, M. & Blatt, R. Experimental multiparticle entanglement dynamics induced by decoherence. Nature Phys. 6, 943 (2010).

Kampermann, H. & Bruß, D. Experimental generation of pseudo-bound-entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 81, 040304(R) (2010).

Lavoie, J., Kaltenbaek, R., Piani, M. & Resch, K. J. Experimental Bound Entanglement in a Four-Photon State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 130501 (2010).

Brukner, Č., Żukowski, M., Pan, J. W. & Zeilinger, A. Bell's Inequalities and Quantum Communication Complexity. Phys. Rev. Lett 92, 127901 (2004).

Smolin, J. Four-party unlockable bound entangled state. Phys. Rev. A 63, 032306 (2001).

Horodecki, R. & Horodecki, P. Generalized Smolin state and their properties. Phys. Rev. A 73, 012318 (2006).

Hiesmayr, B. C., Hipp, F., Huber, M., Krammer, P. & Spengler, Ch. Simplex of bound entangled multipartite qubit states. Phys. Rev. A 78, 042327 (2008).

Horodecki, R. & Horodecki, M. Information-theoretic aspects of inseparability of mixed states. Phys. Rev. A 54, 1838 (1996).

Tóth, G. & Gühne, O. Entanglement detection in stabilizer formalism. Phys. Rev. A 72, 022340 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Pawel Horodecki for useful discusions. This work is supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR) and ERC Advanced Grant QOLAPS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.A. and M.S. conducted the experiment. The data analysis was done by E.A. and the paper was written by E.A. and M.B.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Amselem, E., Sadiq, M. & Bourennane, M. Experimental bound entanglement through a Pauli channel. Sci Rep 3, 1966 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01966

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01966

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.