Abstract

We consider a dynamical network model in which two competitors have fixed and different states and each normal agent adjusts its state according to a distributed consensus protocol. The state of each normal agent converges to a steady value which is a convex combination of the competitors' states and is independent of the initial states of agents. This implies that the competition result is fully determined by the network structure and positions of competitors in the network. We compute an Influence Matrix (IM) in which each element characterizing the influence of an agent on another agent in the network. We use the IM to predict the bias of each normal agent and thus predict which competitor will win. Furthermore, we compare the IM criterion with seven node centrality measures to predict the winner. We find that the competitor with higher Katz Centrality in an undirected network or higher PageRank in a directed network is most likely to be the winner. These findings may shed new light on the role of network structure in competition and to what extent could competitors adjust network structure so as to win the competition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Competition among a set of competitors for obtaining a maximum number of votes from other agents in a social network is a both important and common phenomena in real world. The competitors could be candidates in numerous leader-selection cases, ranging from head–election in a small group to president-election in a whole country1. They could also be those who have different proposals or promote different brands of a product such as mobile phone and car2. There have also been some researches on, for example, how the fractions of speakers of several competing languages evolve in time3 and even how the emerging Bitcoins appear to be a possible competitor to usual currencies4.

The most well-known model in social dynamics for the competition of species is the voter model5,6, which has also later on been used for the analysis of diffusion of innovations and consumption decisions. In its simplest form, each agent in the voter model holds one of the two states. At each time step, a randomly selected agent takes the state of one of its neighbors. Over the years, many modifications and extensions of the original voter model have been proposed7. Voter-like dynamics on networks with different topologies and the interplay between topology and dynamics have also been investigated8,9. However, many of such models, including the voter model, Sznajd model10,11, Deffuant model12, Hegselmann-Krause model13 and so on have been focused on whether full consensus can be reached.

A nature way to consider the existence of competitors in a network is to view them as zealots14,15 or stubborn agents16,17,18 with fixed and different states. For example, it is shown that the existence of competing zealots in the voter model prevents convergence and results in fluctuations in regular lattices14 and complete graphs15. Competitive dynamics with continuous states in the stochastic gossip model is investigated in Ref.16, in which long-run disagreements and persistent fluctuations appear. Influence of network structure and locations of stubborn agents on the fluctuation of final states in a binary opinion formation model is studied in Ref. 17. In Ref. 18,given one set of stubborn agents as mis-informers (agents who spread misinformation), the placement of the other set of stubborn agents (named information disseminators) is formulated as an optimization problem.

The question we address in this work is: How do positions of competitors in a network affect voting outcome? That is, can we predict which competitor will win in the sense that majority of agents in the network will eventually support the competitor? Can we predict which competitor a normal agent will support based on the network structure? Intuitively, the problem of which competitor will win should be related to the relative impact of the competitors in a network. How to characterize the impact or importance of an individual (or even a community) in a network is a question of great importance and applications in network analysis. Traditionally, identifying such influential nodes usually relies on concepts of centralities, including degree (DC), betweenness (BC)19, closeness (CC)20, eigenvector centrality (EC)21, Katz centrality (KC)22, PageRank (PR)23 and so on. Recently, a lot of researches have also been focused on identifying influential nodes in dynamical processes on networks. For example, Kitsak et al. have argued that there are circumstances in which a node with the highest DC or the highest BC has little effect and the most efficient spreaders are those located within the core of the network as identified by the k-shell decomposition24. However, till now, we still lack an understanding on which of these measures could best predict the winner among competitors in a network.

Results

A dynamic model for competition

We consider a directed and weighted network with N agents and M links. The agent set is denoted as  and the topology of the network is described by a coupling matrix A = (akl)N×N: if agent k is directly influenced by agent l, then there is a link from agent k to agent l and akl > 0; otherwise, akl = 0. For simplicity, we assume that there are just two competitors in the network, denoted as agents i and j, which have fixed and different states as follows:

and the topology of the network is described by a coupling matrix A = (akl)N×N: if agent k is directly influenced by agent l, then there is a link from agent k to agent l and akl > 0; otherwise, akl = 0. For simplicity, we assume that there are just two competitors in the network, denoted as agents i and j, which have fixed and different states as follows:

Every other agent (called normal agent) k∈V/{i, j} has a random initial state and updates its state as follows:

where xk(t) is the state of agent k at time t; the parameter ε captures the level of neighbors' influence; Nk = {l∈V|akl > 0} is the set of neighboring agents of agent k that can directly influence agent k. Note that Eq. (2) belongs to a set of distributed consensus protocols, which can be traced back to the classical model of DeGroot25. However, the existence of competitors in the network prohibits global consensus. Instead, we have the following convergence result:

Suppose that

-

1

Each normal agent has a path connecting to at least one competitor;

-

2

, where Dmax is the largest out-degree of agents in the network.

, where Dmax is the largest out-degree of agents in the network.

Then the state of each normal agent will eventually reach a steady value, i.e., as t→∞,

where Xnorm∈RN−2 represents the state vector of all normal agents and  ,

,  and

and  can all be derived from the network coupling matrix A. Furthermore, if xk(0)∈[−1, +1], ∀k∈V/{i, j}, then xk(t)∈[−1, +1], ∀t > 0. The detailed analysis can be found in Methods.

can all be derived from the network coupling matrix A. Furthermore, if xk(0)∈[−1, +1], ∀k∈V/{i, j}, then xk(t)∈[−1, +1], ∀t > 0. The detailed analysis can be found in Methods.

The sign of the steady state of each agent indicates his or her bias:  (

( ) implies that agent k will finally support competitor i (j) and

) implies that agent k will finally support competitor i (j) and  corresponds to the degree of supporting.

corresponds to the degree of supporting.  implies that agent k will be a neutral agent which does not support or against any competitor. Denote

implies that agent k will be a neutral agent which does not support or against any competitor. Denote

where sgn() is the sign function. If Φij > 0, then competitor i will win in the sense that more normal agents will support him; if Φij < 0, competitor j will win; if Φij = 0, the competition ends up with a draw.

An illustration example

Fig. 1 shows the competitive dynamics on three simple undirected networks which have the same number of agents but different coupling structures. We take agent 1 and agent 10 as two competitors in each network with fixed states x1 ≡ +1 and x10 ≡ −1. Steady states of normal agents are computed according to Eq. (3). An red (blue) node represents an agent with positive (negative) state. The darker the color the larger the absolute value of the state. Nodes with white color represent neutral agents.

An example of how network structure influences the competition result.

(a) A simple undirected network of 10 agents with each edge of unit weight. The competition between agent 1 and agent 10 ends up as draw. (b) The network is derived from (a) by adding one edge between agent 2 and 6, which results in agent 10 being the winner. (c) The network has the same structure as network (a) but with different edge weights, which leads to agent 1 being the winner.

For network (a), Φ1,10 = 0, hence the competition ends up as draw. Network (b) is derived from network (a) by just adding one edge between agents 2 and 6, which results in Φ1,10 = −1 and agent 10 being the winner. By changing weights of edges in network (a), we get network (c), which leads to Φ1,10 = 3 and agent 1 winning the competition. We can see that both network structure and coupling weights influence the competition results. In the following, we will focus on unweighted networks in the sense that the weight of every link in a network is one.

Verification on a real network

To see whether Eqs. (1)–(2) could properly model competition in real social networks, we test it on a commonly used benchmark model in social network analysis---the Zachary's karate club network26 as shown in Fig. 2(a), which is a network of friendships between 34 members of a karate club at a US university in the 1970s. Due to the confliction between the manager (agent 34) and the coach (agent 1), the club finally splits into two communities, centered at the manager and the coach, respectively, as depicted by the vertical dashed line in Fig. 2(a).

Verification of the model on Zachary's karate club network.

(a) Two real communities in the network led by agent 1 and agent 34, respectively, as divided by the dashed line in the figure. (b) Two communities derived from our model. Red community consists of supporters of agent 1 and blue community consists of supporters of agent 34. Darkness of the color represents the degree of supporting.

In simulation, we fix the states of agents 1 and agent 34 at +1 and −1, respectively. The state of every other agent evolves according to Eq. (2). Fig 2(b) shows the steady states of all agents in the network, in which red agents are supporters of agent 1 and blue agents are supporters of agent 34. It is surprising to note that this splitting result completely matches the real situation as shown in Fig. 2(a). Furthermore, Fig. 2(b) also reveals the degree of supporting of each normal agent, represented by the darkness of the color. For example, agent 9 has the smallest absolute value of steady state among those supporters of agent 34, which implies that agent 9 is the weakest supporter of agent 34. This is also consistent with the reality that individual 9 is indeed the weakest political supporter of the manager26. Therefore, although our model is a very simplified version of the very complex real-world competition, it might be a reasonable mechanism for the competitive dynamics in some real social networks. Note that many network community detection methods can correctly reveal the two communities in the karate network27, however, they do not explicitly use the information of the two competitors in the network and cannot reveal the degree of supporting of each agent towards the corresponding competitor.

Influence Matrix Criterion

From the steady states expression in Eq. (3), competition results are fully determined by network structure and positions of the competitors in the network. However, directly computing the steady states according to Eq. (3) is computational inefficient for large-scale networks, since for every different pair of competitors, we have to re-compute the steady states. In the following, we compute the Influence Matrix (IM), in which each element characterizes the impact of one agent on another. Note that if there is a link from agent k to l, i.e., akl = 1, then agent l has a direct impact on agent k. If there is a link from agents k to m and a link from agent m to l, then agent l has an indirect impact on agent k via agent m. Intuitively, such an indirect impact should be weaker than the direct impact. Taking into account the fact that the number of paths of length r from agent k to l is (Ar)kl in the unweighted network case, we define IM as a sum of the exponentially decreasing impact of increasingly paths:

where η∈(0, 1) is an attenuation factor. If  , where λ1 is the largest eigenvalue of matrix A, then the above series converges28 and we have:

, where λ1 is the largest eigenvalue of matrix A, then the above series converges28 and we have:

Let fki be the entry of F on k th row and i th column. Denote

We have the following IM criterion:

-

Which competitor will a normal agent support: If fki > fkj (fki < fkj), then agent k will support competitor i (j); If fki = fkj, then agent k is a neutral agent;

-

Which competitor will win: If Γij > 0 (Γij < 0), then competitor i (j) will win; If Γij = 0, the competition ends up with a draw.

Note that other measures of influence of an agent or a group of agents in a network were proposed in Ref. 29–31. The basic idea is to assume that these agents are “forceful” agents which always hold zero states and the influence of these agents in a network is captured by the sum over all entries of the inverse of a corresponding reduced-order matrix, which is determined by the dynamics of the normal agents. Efficient algorithms were also proposed to identify the most influential agents in order to avoid computing matrix inverse for each given forceful agent29,30,31. The main benefits of the IM are that we only need to compute the matrix inverse in Eq. (6) once and can then predict competition result for each given pair of competitors, including which competitor will win and which competitor each normal agent will support.

Although different choice of η in Eq. (6) may generally result in different IM, we find that the IM criterion is robust with respect to η, in the sense that the criterion gives similar qualitative prediction for different choice of  (see Supplementary Figure S1). In the following simulations, we set

(see Supplementary Figure S1). In the following simulations, we set  .

.

For the Zachary's karate club network, Fig. 3 shows the difference fk,1 − fk,34 between the influences of two competitors (agent 1 and agent 34) on a normal agent k. Comparing Fig. 3 with Fig. 2(b), we can see that fk,1 − fk,34 > 0 (fk,1 − fk,34 < 0) if and only if  (

( ), which implies that the competition result can be fully predicted by the IM criterion in this case.

), which implies that the competition result can be fully predicted by the IM criterion in this case.

Application of the IM criterion to Zachary's karate club network.

Agent 1 and agent 34 are two competitors. A normal agent is colored red (blue) if the influence difference fk1 − fk34 > 0 (fk1 − fk34 < 0). We dye all the nodes according to their normalized difference. The darker the color the larger the absolute difference is.

In general, for a given pair of competitors i and j in a network, we use the IM criterion to predict the bias of each normal agent and calculate the success rate of prediction as follows:

where g(x) = 2, if x = 0; otherwise g(x) = 0. The average success rate of prediction on the bias of normal agents over all the N(N − 1)/2 possible pairs of competitors in a network is denoted as <ρ>. Similarly, the success rate of prediction on who will win as the fraction of correct prediction over all the possible pairs of competitors can be formulated as follows:

Table I shows the value of <ρ> and σ for 16 real social networks. The maximum value of <ρ> is 91.6%, the minimum is 74.0% and the average is 83.8%. σ is almost always larger than 80%: the maximum is 96.9%, the minimum is 79.9% and the average is 86.1%. These results verify the validity of the IM criterion. We conjecture through simulation that for most pairs of competitors the prediction of a normal agent's bias being incorrect is because two competitors have very similar influence on the normal agent (see Supplementary Figure S2).

Comparison with centrality-based criteria

Given a pair of competitors, the IM criterion can not only predict which competitor will win but also predict the bias of each normal agent. Intuitively, the winner should be more important or have higher impact on the network than the loser. Over the years, a number of centrality measures have been proposed to characterize the “importance” or “impact” of a node in a network. However, one difficulty in applying these centrality measures is that it is often unclear which of the many measures should be used in a particular circumstance. Here, we compare the IM criterion with criteria based on several common-used node centrality measures, including betweeness (BC), closeness (CC), degree (DC), eigenvector (EC), Katz (KC), K-Shell (KS) and PageRank (PR) (see Methods for the computation of these measures).

Centrality-based criterion. The competitor with higher centrality value will win. Competitors with the same centrality value will end up with a draw.

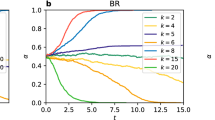

To compare these criteria, we select 16 real networks of different sizes, including 8 undirected and 8 directed networks (see Table I). For each criterion, we calculate the success rate of prediction as the fraction of correct prediction of who will win over all N(N − 1)/2 possible pairs of competitors in each network (see Fig. 4–5). According to the average success rate over undirected and directed networks, we have the following order:

-

For undirected networks: KC (84.8%), IM (84.4%), EC(79.7%), PR (78.4%), DC (77.8%), BC (69.4%), KS (61.4%), CC (39.6%).

-

For directed networks: PR (92.9%), KC (88.5%), IM (87.9%), EC(86.9%), DC (80.5%), BC (77.7%), KS (63.9%), CC (39.5%).

We can see that criteria based on KC, PR, IM and EC are always better than the criteria based on the other four centralities. For undirected networks, KC criterion has the best performance: It provides highest success rate of prediction in 5 of 8 networks. On the other hand, PR criterion is always the best for each of the 8 directed networks. From the definition of KC, PR and EC (see Methods), these results imply that whether a competitor could win depends to a large extent on both the number and importance of those agents that the competitor could directly influence.

In fact, the KC of node i can be directly defined from IM as the influence of node i on the whole network:

The KC-based prediction criterion can be derived from the IM criterion by just changing the order of summation and sign function in Eq. (7):

where KCi is the KC value of node i (For a directed network, we just need to add one more term (fji − fij) in the sum). Directly summing up the influence errors in Eq. (11) may help reduce perturbation and thus result in more robust criterion. This might explain why KC criterion is better to predict the winner than the IM criterion. PageRank is basically a variant of Katz centrality which is widely used for ranking nodes in directed networks such as WWW32. Although IM criterion is not the best, an advantage of IM criterion over node-centrality based criteria is that it could also predict the bias of each normal agent, in addition to predict the winner.

Degree (DC) is certainly the simplest criterion to predict the winner. However, it is a bit surprising to see that DC criterion provides as high as 80% success rate of prediction and performs even better than criteria based on BC, KS and CC. This implies that the number of agents that competitors could directly influence is still a relatively important factor. On the other hand, CC turns out to be the poorest criterion to predict the winner: the corresponding average success rate is just a little bit better than that of the completely random guessing (33.3%). Note that CC of a node captures how long it will take to spread information from the node to all other nodes sequentially. Our results show that this score has little effect on the competition.

Discussion

In summary, we study a model of competitive dynamics in which two competitors have fixed and different states and each normal agent adjusts its state according to a distributed consensus protocol. The steady states of normal agents are fully determined by the network structure and positions of competitors in the network. Although real world competition involves a number of complex factors, we find that this very simple model can completely reveals the competition result in the well-known Zachary's karate club network. We propose the Influence Matrix (IM) criterion to predict which competitor a normal agent will support and which competitor will win. By simulations on 16 real networks of different sizes, we verify the effectiveness of the criterion on predicting which competitor each normal agent will support. We also compare the IM metric with those centrality measures on predicting which competitor will win. Though Katz centrality (KC) and PageRank (PR) provide best prediction for undirected and directed networks, respectively, these classical centrality measures cannot be applied to predict the bias of normal agents.

These findings suggest that competitors in a network might use techniques such as PageRank optimization33 to adjust network structure in order to win the competition. Although we assume that there are only two competitors in the model, the above analysis can also be generalized to the case with two sets of competitors in a network and a nature way to deal with this case is to view all agents in a set as a super-agent. However, a key challenge here is that there does not existing a simple relationship between the sum of the centrality values of all agents in a set in the original network and the centrality score of the super-agent in the new network. All these issues will be considered in future work.

Methods

Theoretical analysis of the model

Eqs. (1) – (2) can be can be rewritten in the following matrix form:

where IN is an identity matrix; L = D − A is the Laplacian matrix, D is the diagonal matrix of agents' out-degrees; H is an indicative diagonal matrix with H(s, s) = 0 if agent s is a competitor and H(s, s) = 1 otherwise. Obviously, the sum of each row of matrix T equals to 1.

For convenience, we reorder the agents so that the two competitors come last. Thus, we have

where di and dj denote the out-degrees of competitor i and j, respectively; vectors ci, cj, ri and rj contain the corresponding elements in the reordered coupling matrix.

Hence, Eq.(12) can be rewritten as

where Xnorm ∈ RN−2 represents the state vector of all normal agents;  and

and  . Thus,

. Thus,

If each normal agent has a path connecting to at least one competitor, then  is invertible34. Since

is invertible34. Since  , we can show from Geršgorin disk theorem that the spectral radius of Q is less than 1. Thus, as t→∞, we have

, we can show from Geršgorin disk theorem that the spectral radius of Q is less than 1. Thus, as t→∞, we have

According to Lemma 4 in Ref. 35, each entry of  is nonnegative and each row sum of

is nonnegative and each row sum of  is equal to one. Thus, the steady state of each normal agent is a convex combination of +1 and −1.

is equal to one. Thus, the steady state of each normal agent is a convex combination of +1 and −1.

Computation of centrality measures

We use a MATLAB toolbox called ‘octave-networks-toolbox’ to compute the centrality measures36. To be self-contained, we give the definition of these measures as follows (note that in our definition, an link from agent k to agent l means agent k could be directly influenced by agent l):

In-BC37: the in-betweenness centrality of node l is computed by  , where gkm is the number of geodesics from node k to node m and gkm(l) is the number of geodesics that node l is on;

, where gkm is the number of geodesics from node k to node m and gkm(l) is the number of geodesics that node l is on;

In-CC38: the in-closeness centrality of node l is computed by  , where d(k, l) is the shortest distance from node k to node l;

, where d(k, l) is the shortest distance from node k to node l;

In-DC: the in-degree of a node is the number of agents that an agent could directly influence;

In-EC21: the eigenvector centrality is a natural extension of degree by considering both the number and the importance of those agents that an agent could directly influence. The EC of a network is equal to the eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue of the coupling matrix. According to the definition of the network structure, we use AT to compute the In-EC;

In-KC: the Katz Centrality is a variation of EC, by adding an initial importance to each agent. The In-Katz-Centrality of a network is computed by (I − αAT)−11, where 1 is a vector with all ones of an appropriate size and the attenuation factor. Related studie39 shows that there is no significant change in ranking of nodes based on Katz Centrality with  . In simulations, we set

. In simulations, we set  ;

;

In-KS40: nodes are assigned to different in-shells according to their remaining in-degrees, which is obtained by successive pruning of nodes with in-degree smaller than the current in-k-shell value. We start by removing all nodes with in-degree kin ≤ 1, until that all nodes left are with in-degree larger than 1. The removed nodes, along with the corresponding links, form an in-k-shell with index kins = 1. In a similar fashion, we iteratively remove the next in-k-shell. As a result, each node is associated with one kins index;

PageRank: the algebraic expression of the page rank can be formulated as  , where μ is the dampening factor. We use the power method41 to compute the page rank value and set μ = 0.85. The Page Rank is a variation on the Katz Centrality by dividing the importance of those agents which could directly influenced by an agent, by their out-degrees.

, where μ is the dampening factor. We use the power method41 to compute the page rank value and set μ = 0.85. The Page Rank is a variation on the Katz Centrality by dividing the importance of those agents which could directly influenced by an agent, by their out-degrees.

References

Chatterjee, A., Mitrovic, M. & Fortunato, S. Universality in voting behavior: an empirical analysis. Sci. Rep. 3, 1049 (2013).

Ketchen, D. J., Snow, Jr, C. C. & Hoover, V. L. Research on competitive dynamics: Recent accomplishments and future challenges. J. Management 30, 779–804 (2004).

Patriarca, M., Castelló, X., Uriarte, J. R., Eguíluz, V. M. & San Miguel, M. Modeling two-language competition dynamics. Adv. Complex Syst. 15, 1250048 (1–24) (2012).

Bornholdt, S. & Sneppen, K. Do Bitcoins make the world go round? On the dynamics of competing crypto-currencies. arXiv, 1403.6378 (2014).

Clifford, P. & Sudbury, A. A model for spatial conflict. Biometrika 60, 581–588 (1973).

Holley, R. & Liggett, T. Ergodic theorems for weakly interacting infinite systems and the voter model. Ann. Probab. 3, 643–663 (1975).

Castellano, C., Fortunato, S. & Loreto, V. Statistical physics of social dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 591 (2009).

Suchecki, K., Eguíluz, V. M. & San Miguel, M. Voter model dynamics in complex networks: Role of dimensionality, disorder and degree distribution. Phys. Rev. E 72, 036132 (2005).

Moretti, P., Liu, S., Castellano, C. & Pastor-Satorras, R. Mean-field analysis of the q-voter model on networks. J. Stat. Phys. 151, 113–130 (2013).

Sznajd-Weron, K. & Sznajd, J. Opinion evolution in closed community. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 11, 1157–1165 (2000).

Sznajd-Weron, K. & Sznajd, J. Who is left, who is right? Physica A 351, 593–604 (2005).

Deffuant, G., Neau, D., Amblard, F. & Weisbuch, G. Mixing beliefs among interacting agents. Adv. Complex Syst. 3, 87–98 (2000).

Hegselmann, R. & Krause, U. Opinion dynamics and bounded confidence models, analysis and simulation. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 5, 3 (2002).

Mobilia, M. & Georgiev, I. T. Voting and catalytic processes with inhomogeneities. Phys. Rev. E 71, 046102 (2005).

Mobilia, M., Petersen, A. & Redner, S. On the role of zealotry in the voter model. J. Stat. Mech.-Theory Exp. 2007, P08029 (2007).

Acemoglu, D., Como, G., Fagnani, F. & Ozdaglar, A. Opinion fluctuations and disagreement in social networks. Math. Oper. Res. 38, 1–27 (2013).

Yildiz, E., Ozdaglar, A., Acemoglu, D., Saberi, A. & Scaglione, A. Binary opinion dynamics with stubborn agents. ACM Tran. Econ. and Comput. 1, 19 (2013).

Fardad, M., Zhang, X., Lin, F. & Jovanovic, M. R. On the optimal dissemination of information in social networks. Proceedings of the 51st IEEE Conference of Decision and Control (CDC'12), Maui, Hawaii. pp. 2539–2544 (December 10-13 2012).

Freeman, L. C. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 40, 35–41 (1977).

Bavelas, A. Communication patterns in task-oriented groups. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 22, 725–730 (1950).

Gould, P. R. On the geographical interpretation of eigenvalues. Tran. Inst. Br. Geogr. 42, 53–86 (1967).

Katz, L. A new status index derived from sociometric analysis. Psychometrika 18, 39–43 (1953).

Page, L., Brin, S., Motwani, R. & Winograd, T. The PageRank citation ranking: Bringing order to the web. Technical Report, Computer Science Department, Stanford InfoLab (Stanford University, California, 1998).

Kitsak, M., Gallos, L. K., Havlin, S., Liljeros, F., Muchnik, L., Stanley, H. E. & Makse, H. A. Identification of influential spreaders in complex networks. Nat. Phys. 6, 888–893 (2010).

Degroot, M. H. Reaching a consensus. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 69, 118–121 (1974).

Zachary, W. W. An information flow model for conflict and fission in small groups. J. Anthropol. Res. 33, 452–473 (1977).

Fortunato, S. Community detection in graph. Phys. Rep. 486, 75–174 (2010).

Wilkinson, J. H. The algebraic eigenvalue problem. (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1965).

Fardad, M., Lin, F. & Jovanović, M. R. Algorithms for leader selection in large dynamical networks: Noise-free leaders. Proceedings of the 50th IEEE Conference of Decision and Control and European Control (CDC-ECC'11), Orlando, Florida. pp. 2692–2697 (December 12-15 2011).

Lin, F., Fardad, M. & Jovanović, M. R. Algorithms for leader selection in stochastically forced consensus networks. IEEE T. AUTOMAT. CONTR. 59, 1789–1802 (2014).

Fardad, M., Lin, F. & Jovanović, M. R. On new characterizations of social influence in social networks. Proceedings of the 52nd IEEE Conference of Decision and Control (CDC'13), Florence, Italy. pp. 2692–2697 (December 10-13 2013).

Franceschet, M. PageRank: Standing on the shoulders of giants. Commun. ACM 54, 92–101 (2011).

Csáji, B. C., Jungers, R. M. & Blondel, V. D. PageRank Optimization by Edge Selection. Discrete Appl. Math. 169, 73–87 (2014).

Cao, Y., Ren, W. & Egerstedt, M. Distributed containment control with multiple stationary or dynamic leaders in fixed and switching directed networks. Automatica 48, 1586–1597 (2012).

Meng, Z., Ren, W. & You, Z. Distributed finite-time attitude containment control for multiple rigid bodies. Automatica 46, 2092–2099 (2010).

Bounova, G. Matlab Tools for Network Analysis octave-networks-toolbox. URL = http://strategic.mit.edu/downloads.php?page=matlab_networks, released November 2011 (Date of access: May 10 2013).

Brandes, U. On variants of shortest-path betweenness centrality and their generic computation. Soc. Networks 30, 136–145 (2008).

Sabidussi, G. The centrality index of a graph. Psychometrika 31, 58–603 (1966).

Benzi, M. & Klymko, C. A matrix analysis of different centrality measures. arXiv,1312.6722 (2013).

Batagelj, V. & Zaveržnik, M. An O(m) Algorithm for Cores Decomposition of Networks. Adv. Data Anal. Classif. 5, 129–145 (2011).

Erik, A. & Per-Anders, E. Investigating Google's PageRank algorithm. Technical Report, Uppsala University (Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2004).

Leskovec, J., Kleinberg, J. & Faloutsos, C. Graph evolution: Densification and shrinking diameters. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 1, 2–41 (2007).

Lusseau, D., Schneider, K., Boisseau, O. J., Haase, P., Slooten, E. & Dawson, S. M. The bottlenose dolphin community of doubtful sound features a large proportion of long-lasting associations. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 54, 396–405 (2003).

Guimera, R., Danon, L., Diaz-Guilera, A., Giralt, F. & Arenas, A. Self-similar community structure in a network of human interactions. Phys. Rev. E 6, 065103 (2003).

McAuley, J. J. & Leskovec, J. Learning to Discover Social Circles in Ego Networks. Proceedings of the 25th Conference on Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS'12), Lake Tahoe, Nevada. pp. 548–556 (December 3–6 2012).

Girvan, M. & Newman, M. E. Community structure in social and biological networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 7821–7826 (2002).

Newman, M. E. Finding community structure in networks using the eigenvectors of matrices. Phys. Rev. E 74, 036104 (2006).

Krebs, V. Social network analysis software and services for organizations, communities and their consultants. URL = http://www.orgnet.com, released October 2006 (Date of access: May 1 2013).

Massa, P., Salvetti, M. & Tomasoni, D. Bowling alone and trust decline in social network sites. Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conference on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing (DASC'09), Chengdu, Sichuan. pp. 658–663 (December 12-14 2009).

Opsahl, T. & Panzarasa, P. Clustering in weighted networks. Soc. Networks 31, 155–163 (2009).

Leskovec, J., Kleinberg, J. & Faloutsos, C. Graph evolution: Densification and shrinking diameters. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 1, 2–41 (2007).

Adamic, L. A. & Glance, N. The political blogosphere and the 2004 us election: divided they blog. Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Link Discovery (LinkKDD '05), Chicago, Illinois. pp. 36–43 (August 21-24 2005).

Michalski, R., Palus, S. & Kazienko, P. Matching organizational structure and social network extracted from email communication. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing 87, 197–206 (2011).

Kunegis, J., Lommatzsch, A. & Bauckhage, C. The Slashdot Zoo: Mining a social network with negative edges. Proceedings of the 18th International World Wide Web Conference (WWW'09), Madrid. pp. 741–750 (April 20-24 2009).

Choudhury, M. D., Lin, Y. R., Candan, K. S., Xie, L. & Kelliher, A. How does the data sampling strategy impact the discovery of information diffusion in social media? Proceedings of the 4th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM'10), Washington, DC. pp. 34–41 (May 23-26 2010).

Leskovec, J., Huttenloche, D. & Kleinberg, J. Signed networks in social media. Proceedings of the 28th ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI'10), Atlanta, Georgia. pp. 1361–1370 (April 10–15 2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 61374176 and 61104137, the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61221003) and the National Key Basic Research Program (973 Program) of China (No. 2010CB731403).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. envisioned the study. J.Z., Q.L. and X.W. conceived the theoretical analysis. J.Z. designed the experiments and performed the computational analysis. X.W., J.Z. and Q.L. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Liu, Q. & Wang, X. Competitive Dynamics on Complex Networks. Sci Rep 4, 5858 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05858

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05858

This article is cited by

-

Identification of anticancer drug target genes using an outside competitive dynamics model on cancer signaling networks

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Rebels Lead to the Doctrine of the Mean: A Heterogeneous DeGroot Model

Journal of Systems Science and Complexity (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

, where Dmax is the largest out-degree of agents in the network.

, where Dmax is the largest out-degree of agents in the network.