Abstract

Haplotypes can hold key information to understand the role of candidate genes in disease etiology. However, standard haplotype analysis has yet been able to fully reveal the information retained by haplotypes. In most analysis, haplotype inference focuses on relative effects compared with an arbitrarily chosen baseline haplotype. It does not depict the effect structure unless an additional inference procedure is used in a secondary post hoc analysis, and such analysis tends to be lack of power. In this study, we propose a penalized regression approach to systematically evaluate the pattern and structure of the haplotype effects. By specifying an L1 penalty on the pairwise difference of the haplotype effects, we present a model-based haplotype analysis to detect and to characterize the haplotypic association signals. The proposed method avoids the need to choose a baseline haplotype; it simultaneously carries out the effect estimation and effect comparison of all haplotypes, and outputs the haplotype group structure based on their effect size. Finally, our penalty weights are theoretically designed to balance the likelihood and the penalty term in an appropriate manner. The proposed method can be used as a tool to comprehend candidate regions identified from a genome or chromosomal scan. Simulation studies reveal the better abilities of the proposed method to identify the haplotype effect structure compared with the traditional haplotype association methods, demonstrating the informativeness and powerfulness of the proposed method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Haplotype–phenotype association can be evaluated at the global level as well as the haplotype-specific level. The global test examines whether there exists an overall association between the genetic variants of the region and the trait of interest. The specific analysis, often performed after an overall association is detected, aims at evaluating the effects of particular haplotypes and obtaining information of the potentially underlying variants. The standard approach for haplotype analysis is to regress the trait values on the haplotypes and examine the significance of the regression coefficients.1 Although such analysis is suitable for global evaluation, it may not be optimal for haplotype-specific evaluation. After detecting global association, a standard method assesses individual haplotype effects with respect to a pre-determined reference haplotype (eg, the most frequent haplotype). The results can only be interpreted with respect to the reference haplotype, and little is learned about the relationship among non-reference haplotypes. Another popular strategy is to dichotomize the haplotypes of interest and the remaining haplotypes into two groups, and use a group indicator to study the effect of the target haplotypes vs the other.2 This strategy requires selecting a priori which haplotype to target, but such information is usually not available in practice. In addition, lumping all ‘remaining’ haplotype effects can be problematic, especially when grouped haplotypes have different or even opposite effects on the phenotypes.

Ideally, a thorough haplotype-specific analysis should investigate the haplotype effects relative to each other rather than to an arbitrary baseline, as the distinct haplotypes are in essence the different ‘levels’ of one covariate ‘factor’. This is similar to the post hoc pairwise analysis in ANOVA. The pairwise comparisons can identify the source of the overall haplotypic association and differentiate haplotypes with the same or different level of effects. However in practice, such analysis may yield contradictory conclusions on which haplotypes share the same level of effects. Furthermore, the pairwise comparisons are generally underpowered due to the necessity to adjust for the multiple comparisons.

In this report, we introduce a penalized-likelihood based approach to facilitate the investigation of haplotype-specific association using unphased genotype data. Penalized-likelihood approaches are often used for variable selection, and several variants have been adopted for haplotype/multimarker association analysis. The important differences lie in the form of the penalty – by carefully designing the penalty function, one can gear the approach toward accomplishing various desired tasks. Generally speaking, an L2-norm penalty on the regression coefficients (ie, ∑β2h with βh being the regression coefficient) can stabilize inference through smoothing coefficients toward zero, while an L1-norm penalty on the regression coefficients (ie, ∑∣βh∣) has the additional ability to set some coefficients to be identically zero, thus simultaneously performing variable selection and inference stabilization. For example, Malo et al3 use ridge regression (L2 penalty) to assess the effects of a large number of SNPs with many being highly correlated. Smoothing the effects toward zero reduces the variance, thus stabilizing inference. Tanck and colleagues4, 5, 6 use the penalized approach to stabilize inference for rare haplotypes. They construct an L2-norm penalty term not on the coefficients themselves, but on the differences in coefficients of similar haplotypes. By doing so, the coefficients corresponding to rare haplotypes are smoothed toward that of a similar common haplotype. Alternatively, Li et al7 use LASSO regression (L1 penalty) to perform selection among numerous possible haplotypes to find those that differ from the baseline haplotype. Recently, Guo and Lin8 also propose LASSO regression to stabilize haplotype inference, allowing the evaluation of rare haplotype effects and haplotype–environment interactions. However, the individual haplotype effects are evaluated with respect to the baseline haplotype, and performing pairwise comparison analysis under this framework can be non-trivial due to the fact that the distribution of the LASSO estimator is non-standard.

In our penalized-likelihood method, we use an L1 penalty term on pairwise differences to collapse the estimates of haplotypes with the same effects to be exactly equal. Instead of variable selection or inference stabilization, our goal is to identify haplotypes with the same effects and collapse them to a group structure. Unlike current approaches where haplotype inference focuses on relative effects compared with a baseline haplotype, our penalty is designed to perform direct comparisons among all haplotypes. As shown in the simulation studies, our approach not only yields a great deal more information than the typical approach but also exhibits higher power.

Methods

To fix the idea, we consider the simple scenario of a quantitative trait with additive genetic effect. We use an ANOVA-like representation of the haplotype-trait linear model:

where Yhki represents the trait value for individual i with haplotypes h and k, and Ei is a vector of environmental factor. Here γ0 represents a global intercept, vector γ represents the environmental effects, and the βh represents the overparameterized haplotype effects with  (That is, there are L coefficients if L distinct haplotypes are observed in the population.) Note that h and k can be the same so that βh+βk=2βh in the homozygous case. Assume that the error term ɛi∼N(0, σ). Define haplotype matrix Hn × L whose (i, h) element is an indicator of whether individual i possesses haplotype h. Because each individual has two haplotypes, the design matrix for haplotype effect is the sum of the two original haplotype matrices when assuming an additive effect. In general, the design matrix for haplotype effect can be the maximum (minimum) of the two original haplotype matrices for dominant (recessive) effects.

(That is, there are L coefficients if L distinct haplotypes are observed in the population.) Note that h and k can be the same so that βh+βk=2βh in the homozygous case. Assume that the error term ɛi∼N(0, σ). Define haplotype matrix Hn × L whose (i, h) element is an indicator of whether individual i possesses haplotype h. Because each individual has two haplotypes, the design matrix for haplotype effect is the sum of the two original haplotype matrices when assuming an additive effect. In general, the design matrix for haplotype effect can be the maximum (minimum) of the two original haplotype matrices for dominant (recessive) effects.

The global test of association would test H0:β1=β2=…=βL=0 vs Ha: at least one βh is not 0. The follow-up question, which is the haplotype-specific analysis, is to test each of the individual hypothesis H0:βh=βh′ separately. These tests allow for the comparison of all haplotypes to determine the effect structure. Following the idea of the penalized approach to ANOVA,9 we estimate the effects (γ0, γ, β) by (γ̂0, γ̂, β̂), which is the minimizer of

In (1), the first term is equivalent to −2 times the log likelihood under a standard regression with normal error; the value λ>0 is a tuning constant; and the weight for haplotype pair (h, h′) is given by  where

where  denotes an initial consistent estimate of βh (eg, the standard least squares estimate), n(jk) denotes the number of individuals having the unordered haplotype pair (jk) (ie, pair (jk) is treated the same as pair (kj)), and h* refers to any other haplotype except for h or h′. The weight consists of two components. The first term

denotes an initial consistent estimate of βh (eg, the standard least squares estimate), n(jk) denotes the number of individuals having the unordered haplotype pair (jk) (ie, pair (jk) is treated the same as pair (kj)), and h* refers to any other haplotype except for h or h′. The weight consists of two components. The first term  is an adaptive weight10 and inversely weights the haplotype pairs by an initial estimate of their difference in effect. As a result, haplotypes with similar effects can be more readily grouped together, while those that are different remain separated. It has been shown that the adaptive weights have desirable asymptotic properties.9 The second term accounts for the fact that the haplotype frequencies are unequal. In penalized regression, the predictors should be on a comparable scale so that the penalization is carried out equally and balances appropriately with the likelihood. In our case, this avoids the grouping results being dominated by large-count haplotypes. Intuitively, we would want to assign larger-count cells higher penalties to counter balance their larger influence in the likelihood. As opposed to an ad-hoc determination of the weight, we derive the proposed weight based on theoretical considerations (Appendix A). The idea is based on standardizing an appropriate design matrix that corresponds to the pairwise differences under an overparameterized model.

is an adaptive weight10 and inversely weights the haplotype pairs by an initial estimate of their difference in effect. As a result, haplotypes with similar effects can be more readily grouped together, while those that are different remain separated. It has been shown that the adaptive weights have desirable asymptotic properties.9 The second term accounts for the fact that the haplotype frequencies are unequal. In penalized regression, the predictors should be on a comparable scale so that the penalization is carried out equally and balances appropriately with the likelihood. In our case, this avoids the grouping results being dominated by large-count haplotypes. Intuitively, we would want to assign larger-count cells higher penalties to counter balance their larger influence in the likelihood. As opposed to an ad-hoc determination of the weight, we derive the proposed weight based on theoretical considerations (Appendix A). The idea is based on standardizing an appropriate design matrix that corresponds to the pairwise differences under an overparameterized model.

The computation procedure is more conveniently described after rewriting the Lagrangian formulation of (1) as an equivalent constrained optimization problem:

Now the constrained minimization depends on an unknown tuning constant t, which has a one-to-one correspondence to the constant λ. We use BIC to choose the appropriate t, from a range of gridded values that t can take. The value of t has an upper bound at  (ie maximization with no penalty). The grid search can then be conducted by a constant u∈(0, 1), with the relationship between t and u as

(ie maximization with no penalty). The grid search can then be conducted by a constant u∈(0, 1), with the relationship between t and u as  For a given t, we compute the estimated coefficients by the EM algorithm to tackle the phase-unknown problem (Appendix B), and calculate BIC=−2 logL+log(n)df, where L is the value of the likelihood evaluated at the estimated parameters, and df is the degrees of freedom. The quantity df=(L*−1)+K+1, where L*≤L is the number of estimated unique haplotype effects, and K+1 is the dimension of the vector (γ0, γ). The model that minimizes the BIC criterion is the one chosen and interpreted. We choose BIC as the tuning method because our goal is to select the true model structure and BIC has the property of consistency in model selection.11, 12, 13, 14 An alternative criterion would be to use a cross-validation (CV) criterion. However, as CV targets prediction error, it is less of interest with regard to finding the model structure.

For a given t, we compute the estimated coefficients by the EM algorithm to tackle the phase-unknown problem (Appendix B), and calculate BIC=−2 logL+log(n)df, where L is the value of the likelihood evaluated at the estimated parameters, and df is the degrees of freedom. The quantity df=(L*−1)+K+1, where L*≤L is the number of estimated unique haplotype effects, and K+1 is the dimension of the vector (γ0, γ). The model that minimizes the BIC criterion is the one chosen and interpreted. We choose BIC as the tuning method because our goal is to select the true model structure and BIC has the property of consistency in model selection.11, 12, 13, 14 An alternative criterion would be to use a cross-validation (CV) criterion. However, as CV targets prediction error, it is less of interest with regard to finding the model structure.

The above framework can be extended straightforwardly to generalized linear model (GLM) to allow other trait types. The density is of the form  where a, b, and c are known functions, σ is a scale parameter, and η=γ0+Eγ+βh+βk in the case of additive haplotype effects. The previous model for quantitative traits is a special case using the normal distribution. Another common example is binary traits, in which Y is assumed to have a Bernoulli distribution. By choosing the logit link function, this results in logistic regression. For the GLM, estimation proceeds by minimizing the deviance (ie, −2 × log Likelihood) with the penalty to accomplish the pairwise comparisons:

where a, b, and c are known functions, σ is a scale parameter, and η=γ0+Eγ+βh+βk in the case of additive haplotype effects. The previous model for quantitative traits is a special case using the normal distribution. Another common example is binary traits, in which Y is assumed to have a Bernoulli distribution. By choosing the logit link function, this results in logistic regression. For the GLM, estimation proceeds by minimizing the deviance (ie, −2 × log Likelihood) with the penalty to accomplish the pairwise comparisons:

For a normally distributed trait value, this reduces to (1).

Simulation studies

We performed simulation studies to examine the performance of the proposed penalized regression method. To compare, we also conducted the standard haplotype regression analyses using the method of Lake et al15 (as implemented in the R function ‘haplo.glm’) followed by the post hoc pairwise analysis to perform the haplotype-specific analysis. We carried out two types of the post hoc comparisons: The ‘Unadjusted’ method performs the pairwise analysis without adjusting for multiple comparisons. The ‘FDR-adjusted’ method used the Benjamini and Hochberg's procedure16 to control for the false discovery rate (FDR) in the multiple comparisons. We also performed, but did not report the analyses that control for the family-wise error rate, as their power was much lower than the others.

We considered three simulation studies: two based on the two gene regions (Renin and AGTR1) reported in French et al,17 and one based on a region on chromosome 18 of the CEU sample in the HapMap data, as in Lin and Huang.18 In each simulation study, we normed the common haplotype frequencies and then randomly sampled n haplotype pair. Given certain pre-specified causal haplotypes (listed in Table 1), we then generated normal traits and binary traits based on the model g(μi)=θ0+θTHi, where μi≡E(Yi∣Hi) is the conditional trait mean given haplotypes, θ0 is the effect of baseline haplotype, θ(L−1) × 1 is the effect vector of the remaining haplotypes representing the difference from baseline, and Hi is the design vector for the haplotype pairs of individual i. As our focus is to evaluate the relative performance of the standard analysis vs our proposed strategy, we generated the data in a prospective manner, so to obtain the best inference results from haplo.glm. We set the parameters in a way that the power of the unadjusted method and the FDR-adjusted method fell within a reasonable range. Specifically, for normal traits, we set g(·) to be the identity link, θ0=0, and the trait variance var(Yi∣Hi) to be 1.5 (which resulted in a heritability of about 5%). For binary traits, g(·) is the logit link and θ0=−2 (corresponding to a disease rate of 14%).

In the simulation analyses, we used only unphased genotypes and carried out 1000 replications. To determine whether each pair of haplotypes should be grouped together or not,  separate tests must be performed. For example, to test for a difference between haplotypes h and k, we test H0:θh=θk. For haplotype h compared with the baseline, we test H0:θh=0. Note that by performing all tests, the choice of baseline is irrelevant. For our method, the significance of a test is determined by checking whether the regression coefficients have identical estimates. For the standard method, each test is performed by using asymptotic normal distribution of θ̂h−θ̂k as given by Lake et al.15 The results were evaluated using the five criteria described in Table 2.

separate tests must be performed. For example, to test for a difference between haplotypes h and k, we test H0:θh=θk. For haplotype h compared with the baseline, we test H0:θh=0. Note that by performing all tests, the choice of baseline is irrelevant. For our method, the significance of a test is determined by checking whether the regression coefficients have identical estimates. For the standard method, each test is performed by using asymptotic normal distribution of θ̂h−θ̂k as given by Lake et al.15 The results were evaluated using the five criteria described in Table 2.

We first examined the type I error rate of the proposed method. We set θ to be a zero vector in the three simulation studies and measured the overall type I error rate in testing the hypothesis of no global association (ie, H0: θ1=…=θL−1=0). The results are listed in Table 3. The overall type I error rates of the proposed method (or equivalently, 1−‘Null’ criterion) for a sample size of 1000 ranged around 0.05–0.08. The error rate will decrease with an increased sample size because of the asymptotic theory.9

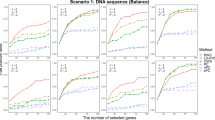

Next we perform the power analysis. In Simulation 1, based on gene Renin, we considered three scenarios for haplotype effects with n=500: (1) one causal haplotype with θT=(θV, θW, θX, θY, θZ)=(0, 0, 0, 0.5, 0); (2) two causal haplotypes with θT=(1, 0, 0, 0.5, 0); and (3) two causal haplotypes with θT=(0, 0, 1, 0.5, 0). The results are summarized in Figure 1 (Figure 2) for normal (binary) traits. Generally speaking, line ‘0’ (ie, results of our method) lies above all other lines in all five criteria and across different scenarios, indicating that the proposed method consistently performs better than the traditional approaches. In figures, lines ‘1’ to ‘3’ (‘a’ to ‘c’) are the results of the unadjusted (FDR-adjusted) method at various nominal levels of 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2. The standard method must compromise between true negatives and true positives (eg, the lines cross between the ‘Null’ and ‘Effect’ categories). On the contrary, the proposed method does not suffer from this shortcoming. It was able to reach a better balance between true negative and true positive, and therefore can identify more accurately the underlying group structure among the haplotypes.

Proportion of correct identification of haplotype group structures for normal traits in Simulation 1. Line ‘0’ indicates the results of the proposed penalized method. Lines ‘1’ to ‘3’ indicate the results of the unadjusted method at the per-comparison type I error rates of 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively. Lines ‘a’ to ‘c’ indicate the results of the FDR-adjusted methods at the overall false discovery rates at 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively. For the definition of the x axis (eg, ‘Null’, ‘Effect 1’ and so on), please refer to Table 2.

Proportion of correct identification of haplotype group structures for binary traits in Simulation 1. Line ‘0’ indicates the results of the proposed penalized method. Lines ‘1’ to ‘3’ indicate the results of the unadjusted method at the per-comparison type I error rates of 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively. Lines ‘a’ to ‘c’ indicate the results of the FDR-adjusted methods at the overall false discovery rates at 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively.

Comparing Scenarios (2) with (3), we observed a clear power decrease in the ‘Effect 2’. This is because, in Scenario (3), the rare haplotype V is now one of the null ones, which makes it harder to detect a difference between the null haplotype V and the Effect 2 (ie, small-effect) haplotype. This power drop was especially severe for the traditional approaches because of the small sample size for that comparison. The relative power loss in Scenario (3) to Scenario (2) is about 33–58% (41–83%) for normal (binary) traits with the traditional methods, and is only 10% (15%) for normal (binary) traits with the proposed method.

In Simulation 2, based on gene AGTR1, we considered three levels of effect sizes, which partition the haplotypes into ‘Effect Null’ (with five null haplotypes), ‘Effect 1’ (with two causal haplotypes of θh=1), and ‘Effect 2’ (with two causal haplotypes of θh=0.5). The results with n=1000 for both traits are shown in Figure 3. Because each effect group now contains more than one haplotype, we further considered two subcriteria when evaluating true positive rates: (a) ‘Detected’ (ie, the proportion that the same-effect causal haplotypes are found significant from all null haplotypes, regardless of whether they are grouped together or not), and (b) ‘Exact’ (ie, the proportion that the same-effect causal haplotypes are found significant from all null haplotypes and are grouped together). We observed a similar pattern as in Simulation 1: compared with the standard methods, the proposed method has comparable or higher true negative rates and true positive rates; it yields a better balance between the two rates and results in a better overall performance.

Proportion of correct identification of haplotype group structures for normal traits and binary traits in Simulation 2. Line ‘0’ indicates the results of the proposed penalized method. Lines ‘1’ to ‘3’ indicate the results of the unadjusted method at the per-comparison type I error rates of 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively. Lines ‘a’ to ‘c’ indicate the results of the FDR-adjusted methods at the overall false discovery rates at 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively.

In Simulation 3, based on the HapMap data, we considered two scenarios: (1) one causal haplotype, and (2) two same-effect causal haplotypes. The results are shown in Figure 4 (for normal traits) and Figure 5 (for binary traits). Same as what observed previously, the proposed method outperformed the standard methods in true negative rates, true positive rates and overall performance under different scenarios and trait types.

Proportion of correct identification of haplotype group structures for normal traits in Simulation 3. Line ‘0’ indicates the results of the proposed penalized method. Lines ‘1’ to ‘3’ indicate the results of the unadjusted method at the per-comparison type I error rates of 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively. Lines ‘a’ to ‘c’ indicate the results of the FDR-adjusted methods at the overall false discovery rates at 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively.

Proportion of correct identification of haplotype group structures for binary traits in Simulation 3. Line ‘0’ indicates the results of the proposed penalized method. Lines ‘1’ to ‘3’ indicate the results of the unadjusted method at the per-comparison type I error rates of 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively. Lines ‘a’ to ‘c’ indicate the results of the FDR-adjusted methods at the overall false discovery rates at 0.05, 0.10 and 0.20, respectively.

Discussion

A careful understanding of haplotype-specific effects can provide information on the potentially underlying variants. It can also suggest biological hypotheses that form foundations for follow-up molecular genetic experiments, such as to investigate the effects of ‘knock-in’ or humanization of an experimental model by incorporating a specific human haplotype. Although many methods are available to evaluate haplotypic effects either at the global level or the individual level, few enable a systematic and informative examination of haplotype effects while maintaining statistical power and inference stability. In this study, we advocate to characterize the effect structure of haplotypes. We introduce a penalized regression approach to efficiently evaluate individual haplotype effects with respect to each other and to identify the haplotype group structure based on their effect sizes. Using the penalty term allows us to combine the estimation and testing steps, and bypasses the issues associated with multiple testing. The proposed method is both informative and powerful, and can serve as a tool to comprehend candidate regions identified from a genome-wide or chromosome-wide scan. The R code that implements this method is available from the authors’ website at http://www4.stat.ncsu.edu/~jytzeng/Softwares/PLHap/R/.

Compared with standard haplotype-based analysis, our approach provides interpretable results that could be used to reveal the potential effects of the functional variants. For example, in Simulation 2, given the grouping structure, we can infer a potential causal SNP2 with different interacting effects with SNP1 and with SNP5 and SNP6. Even compared with SNP-based analysis,19 the proposed method still exhibit advantages: for example, here the SNP analysis may identify the individual effects of SNP1, SNP2 and SNP6, but may miss SNP5 and miss the interactions among these SNPs. Similar situations can be found in Simulations 1 and 3, although we did not illustrate further here.

We have shown the feasibility of the proposed method to study haplotype-specific effects using a prospective likelihood formulation for genetic main effects. The framework can be extended to retrospective likelihood approaches and to include gene–environment or gene–gene interactions. Furthermore, it can also incorporate available evolutionary information to improve the efficiency, in a similar manner as reported in the literature.20, 21 Instead of testing for differences in all pairwise comparisons, Seltman et al20 grouped haplotypes based on evolutionary relationship and carried out a reduced number of sequential tests on the haplotype groups. This evolution-guided grouping idea can be adapted in our procedure through additional weights to each haplotype effect pair in the penalty (1). These weights would reflect the genetic distance between the pair, so that evolutionarily ‘closer’ haplotypes are more likely to be assigned to the same effect group. Another option is to set the weight as a function of the phenetic distance and haplotype frequencies.21 We note that it is well known that the penalized-likelihood solutions can be considered as the posterior mode estimates using a particular choice of the earlier distribution. The weights can then be viewed as including the evolutionary information in the earlier distribution. We intend to fully examine the appropriateness of this approach and consider various weight functions in future work.

References

Purcell S, Daly MJ, Sham PC : WHAP: haplotype-based association analysis. Bioinformatics 2007; 23: 255–256.

Lin DY, Zeng D : Likelihood-based inference on haplotype effects in genetic association studies. J Am Stat Assoc 2006; 101: 89–104.

Malo N, Libiger O, Schork NJ : Accommodating linkage disequilibrium in genetic-association analyses via ridge regression. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 82: 375–385.

Souverein OW, Zwinderman AH, Tanck MW : Estimating haplotype effects on dichotomous outcome for unphased genotype data using a weighted penalized log-likelihood approach. Hum Hered 2006; 61: 104–110.

Souverein OW, Zwinderman AH, Jukema JW, Tanck MW : Estimating effects of rare haplotypes on failure time using a penalized Cox proportional hazards regression model. BMC Genet 2008; 9: 9.

Tanck MW, Klerkx AH, Jukema JW, De Knijff P, Kastelein JJ, Zwinderman AH : Estimation of multilocus haplotype effects using weighted penalized log-likelihood: analysis of five sequence variations at the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene locus. Ann Hum Genet 2003; 67: 175–184.

Li Y, Sung WK, Liu JJ : Association mapping via regularized regression analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphism haplotypes in variable-sized sliding windows. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 80: 705–715.

Guo W, Lin S : Generalized linear modeling with regularization for detecting common disease rare haplotype association. Genet Epidemiol 2009; 33: 308–316.

Bondell HD, Reich BJ : Simultaneous factor selection and collapsing levels in ANOVA. Biometrics 2009; 65: 169–177.

Zou H : The adaptive lasso and its oracle properties. J Am Stat Assoc 2006; 101: 1418–1429.

Shao J : An asymptotic theory for linear model selection. Stat Sinica 1997; 7: 221–264.

Wang H, Li R, Tsai CL : Tuning parameter selectors for the smoothly clipped absolute deviation method. Biometrika 2007; 94: 553–568.

Yang Y : Can the strengths of AIC and BIC be shared? A conflict between model identification and regression estimation. Biometrika 2005; 92: 937–950.

Zou H, Hastie T, Tibshirani R : On the degrees of freedom of the lasso. Ann Stat 2007; 35: 2173–2192.

Lake S, Lyon H, Tantisira K et al: Estimation and tests of haplotype-environment interaction when linkage phase is ambiguous. Hum Hered 2003; 55: 56–65.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y : Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 1995; 57: 289–300.

French B, Lumley T, Monks SA et al: Simple estimates of haplotype relative risks in case-control data. Genet Epidemiol 2006; 30: 485–494.

Lin DY, Huang BE : The use of inferred haplotypes in downstream analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 80: 577–579.

Clayton D, Chapman J, Cooper J : Use of unphased multilocus genotype data in indirect association studies. Genet Epidemiol 2004; 27: 415–428.

Seltman H, Roeder K, Devlin B : Evolutionary-based association analysis using haplotype data. Genet Epidemiol 2003; 25: 48–58.

Tzeng JY : Evolutionary-based grouping of haplotypes in association analysis. Genet Epidemiol 2005; 28: 220–231.

Acknowledgements

JYT was supported by grants NSF DMS-0504726 and NIH R01 MH084022. HDB was supported by NSF DMS-0705968 and NIH R01 MH084022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Derivation of the penalty weights

Here we show that an appropriate set of weights to use in the procedure (in addition to the adaptive weights) are given by  The derivation follows the idea of ‘standardized predictors’ as in Bondell and Reich.9 The penalty term can be viewed as an L1 penalty on the pairwise differences. We hence consider a model that is parameterized in terms of these differences in addition to the coefficients themselves. This is a highly overparameterized model, but the idea is to determine a design matrix that would correspond to this overparameterized model. Then we can ‘standardize’ in that space, resulting in the correct scaling to the predictors in this overparameterized model.

The derivation follows the idea of ‘standardized predictors’ as in Bondell and Reich.9 The penalty term can be viewed as an L1 penalty on the pairwise differences. We hence consider a model that is parameterized in terms of these differences in addition to the coefficients themselves. This is a highly overparameterized model, but the idea is to determine a design matrix that would correspond to this overparameterized model. Then we can ‘standardize’ in that space, resulting in the correct scaling to the predictors in this overparameterized model.

Let δ (with length d=L(L−1)/2) denote the vector of pairwise differences taken within each factor. Let the overparameterized model with (L+d) parameters (arising from the L coefficients plus the d differences) have parameter vector ζ=Mβ=(βT, δT)T. The matrix M is given by M=[IL, DT]T, with IL being the L × L identity matrix, and D the d × L matrix of ±1 that creates δ from β by picking off the pairwise differences.

The corresponding design matrix X for this overparameterized design is an n × (L+d) matrix such that Xζ=Hβ for all β, or equivalently, XM=H. Clearly, this design matrix X is not uniquely defined. Any choice of X=HM*, with M* as any left inverse of M, would suffice. In particular, we choose X=HM−, where M− denotes the Moore–Penrose generalized inverse of M. The weights are then the Euclidean norm of the columns of X that correspond to each difference (ie, the last d columns of X).

Proposition

The Moore–Penrose generalized inverse of the matrix M is given by M−=(L+1)−1[IL+1L1LT, DT], where 1L denotes the L × 1 vector of ones. Furthermore, the column of X=HM− that corresponds to the effect difference for haplotypes h and h′ has Euclidean norm

Proof of proposition

Consider the matrix M−=(L+1)−1[IL+1L1LT, DT]. Then M−M=(L+1)−1[IL+1L1LT, DTD]. By direct calculation, one obtains DTD=LIL−1L1LT, so M−M=IL.

To show that M− is the Moore–Penrose inverse of M, it suffices to show that (1) M−MM−=M−, (2) MM−M=M, (3) M−M is symmetric and (4) MM− is symmetric. Clearly (1), (2) and (3) follow directly from the fact that M−M=IL. For (4),

From the form of D, it follows that D1L1LT=0d × L. Thus the matrix is symmetric, and M− is the Moore–Penrose inverse of M. The Euclidean norm of the columns of X=HM− corresponding to the differences (ie, the last d columns) follows, as these columns of X will contain the elements {0, ±1±2}. Consider a column of this matrix X corresponding to the difference in effect for two haplotypes. The number of ±2 in the column is the number of homozygous individuals for either of the two haplotypes. The number of ±1 in the column is the number of individuals with exactly one of the two haplotypes. Individuals with neither of the two haplotypes, or one of each of them, contribute zero to the column total. Hence, summing up the squares and then taking the root gives the result.

In practice when the phase is unknown, we consider the expected value of the conditional on the observed genotypes, as described in the EM algorithm in Appendix B.

Appendix B

The EM algorithm for penalized regression

The full data log likelihood is given by  where f(Yi∣Hi, Ei) is the GLM density given in (3). Under the assumption of HWE and gene–environment independence, f(Hi∣Ei)=f(Hi) is the density of multinomial (2, Π) where ΠL × 1={πh} is the haplotype frequency.

where f(Yi∣Hi, Ei) is the GLM density given in (3). Under the assumption of HWE and gene–environment independence, f(Hi∣Ei)=f(Hi) is the density of multinomial (2, Π) where ΠL × 1={πh} is the haplotype frequency.

E-Step

We take the expectation of the full data log likelihood conditional on genotype G and the current parameters:

where Hi,h is the (i, h) entry of the design matrix H. The expectation step only involves heterozygous individuals, for whom the last term is always 2log 2 and can be dropped. For each individual, the expectation step creates ‘pseudo observations’ that consist of all haplotype pairs consistent with Gi weighted by its conditional probability given genotypes. That is, each individual will have multiple rows in the ‘pseudo design matrix’ corresponding to their possible haplotype pairs; for a given row, the entries in the columns h and h′ are the conditional probability of haplotype pair (h, h′) given Gi.

M-Step

In the models with normally distributed traits, the maximization step is equivalent to the minimization of a sum of squares as in (2), except that each observation is expanded to all possible haplotypes consistent with the observed genotypes of the individual. Each of these ‘pseudo observations’ has weight that was computed in the expectation step.

To solve (2) by a reparameterization, we get a quadratic loss function with linear constraints. This is then a typical quadratic programing problem and there are numerous standard algorithms available to solve it. The reparameterization, described in Appendix A, results in a fully overparameterized model that includes the intercept γ0, environmental effects γ, haplotype effects β and pairwise differences δ. The 1+K+L+d parameters of this model are estimated under a set of linear constraints that includes: (i)  (ii)

(ii)  where ws is the weight for pair s, the bound t is as in (2), and δs+ and δs− are non-negative values with only one being nonzero such that δs=δs+−δs− (ie, an absolute difference can be expressed as δs++δs−); and (iii) [D, −Id, Id][βT, (δ+)T, (δ−)T]T=0d, where the matrix D is as given in Appendix A and 0d denotes the d × 1 vector of zeros. Constraint (iii) ties together each positive part of the pairwise difference with the negative part of the same difference and ensures that the estimate of the new parameter δ corresponds to the differenced estimates of the original coefficients β.

where ws is the weight for pair s, the bound t is as in (2), and δs+ and δs− are non-negative values with only one being nonzero such that δs=δs+−δs− (ie, an absolute difference can be expressed as δs++δs−); and (iii) [D, −Id, Id][βT, (δ+)T, (δ−)T]T=0d, where the matrix D is as given in Appendix A and 0d denotes the d × 1 vector of zeros. Constraint (iii) ties together each positive part of the pairwise difference with the negative part of the same difference and ensures that the estimate of the new parameter δ corresponds to the differenced estimates of the original coefficients β.

In the GLM, the likelihood is no longer quadratic, but the constraints are still linear. We use a quadratic approximation to the likelihood around the current estimate using a Taylor expansion, apply the quadratic programing solver, and iterate until convergence.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tzeng, JY., Bondell, H. A comprehensive approach to haplotype-specific analysis by penalized likelihood. Eur J Hum Genet 18, 95–103 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2009.118

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2009.118

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

High-frequency marker haplotypes in the genomic selection of dairy cattle

Journal of Applied Genetics (2019)

-

Penalized-regression-based multimarker genotype analysis of Genetic Analysis Workshop 17 data

BMC Proceedings (2011)