Abstract

Substrate-based crawling motility of eukaryotic cells is essential for many biological functions, both in developing and mature organisms. Motility dysfunctions are involved in several life-threatening pathologies such as cancer and metastasis. Motile cells are also a natural realisation of active, self-propelled ‘particles’, a popular research topic in nonequilibrium physics. Finally, from the materials perspective, assemblies of motile cells and evolving tissues constitute a class of adaptive self-healing materials that respond to the topography, elasticity and surface chemistry of the environment and react to external stimuli. Although a comprehensive understanding of substrate-based cell motility remains elusive, progress has been achieved recently in its modelling on the whole-cell level. Here we survey the most recent advances in computational approaches to cell movement and demonstrate how these models improve our understanding of complex self-organised systems such as living cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motility—the ability to move spontaneously via consumption of energy delivered by either the internal metabolism or from the environment—is a hallmark of living systems. Eukaryotic cells (i.e., cells with nuclei), such as keratocytes, fibroblasts or neutrophils, move on substrates by forming a thin membrane-surrounded protrusion of the actin cytoskeleton called lamellipodium. The main processes involved in this motion have been identified1,2 by Abercrombie in the 1980s (cf. Figure 1a): (i) the generation of a propulsive force by actin polymerisation against the cell’s membrane;3,4 (ii) the formation of adhesive contact to the substrate to transfer this propulsion force and to move forward;5,6 and (iii) the contractile action of actin-associated molecular motor proteins (myosins) in determining the cell’s polarity7 and to retract the cell’s rear and detach existing adhesive bonds.8–10 Several of these processes—especially actin polymerisation and the action of molecular motors—are far from equilibrium, i.e., rely on the ‘fuel’ provided by the cell’s metabolism in the form of adenosine triphosphate. These processes have been addressed—mostly separately—theoretically, focusing on propulsion,11–13 adhesion14,15 and motor activity,16,17 respectively. More details on the biological background of force generation and transfer in moving cells can be found in a recent review.18

Main physical mechanisms involved in cell motility and their experimental evidence. (a) Illustration of the main physical mechanisms responsible for substrate-based cellular motion: actin polymerisation, substrate adhesion and contraction by molecular motors (for details see text). (b) Distribution of actin filaments (red) and of myosin motors (green) inside a keratocyte (figure reproduced from Barnhart et al.6). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures. (c) Distribution of the actin flow velocity inside moving keratocytes.21 (d) The traction force exerted by a moving keratocyte on the underlying substrate as a consequence of the distributed force transfer.21 Images (c) and (d) are courtesy of Maxime Fournier and Alex Verkhovsky.

The motile cell type that is best studied experimentally so far are fish keratocytes.6,19–29 Importantly, it has been shown19,30 that also keratocyte lamellipodial fragments are able to move, quite similar to entire cells. Fragment formation can be induced by strongly inhibiting the myosin motors, thereby inducing a detachment of (parts of) the lamellipodium from the rest of the cell. Such fragments, deprived of the nucleus and most organelles, move when polarised externally and can be stable for hours. This finding underlined that the motility mechanism of eukaryotic cells is, at least to a substantial degree, a self-organised process. Hence, it can be accessible to physical modelling approaches combining methods from soft matter and nonequilibrium physics, as well as materials science.

Quite recently, whole-cell physical models for moving cells have been under development31–35 to rationalise the rapidly growing volume of experimental results (cf. Figure 1b–d). The models identified major motility mechanisms and demonstrated that the generic aspects of the onset of motion, the selection of the cell’s shape, the traction distribution and many other important features of cell motility are rather independent of specific cell biochemical and regulation pathways and mostly determined by physical factors, such as propulsion force, adhesion, mechanosensitivity, polarisation, etc. The whole-cell models also shed light on the force transfer from the cell to substrate, and gave insights into the onset of collective behaviour of many cells and the navigation of cells on patterned substrates.

Computational modelling of cell movement (and related topics such as tissue dynamics) is a large and very active topic at the frontier between physics, biology and biomedical engineering. Not surprisingly, different computational approaches have been applied to the same biological problem. Since a comprehensive review of all recent studies in this field is beyond the scope of this work, we will focus mostly on the phase-field approach, where the most recent progress in modelling of single and collective cell behaviour was achieved.

Current computational approaches

Sharp interface methods

Cell migration relies on the subtle interplay of multiple physical and biochemical processes, from treadmilling of actin filaments and motor-induced actin network contraction to adhesion formation and maturation and response to external cues (chemotaxis, durotaxis), to name but a few. The actin-based motility machinery of the cell—in fact the cell as a whole—is confined by the cell membrane. While being flexible enough to allow deformation and motion, the membrane is endowed with surface tension and rigidity, which, in turn, also provides a highly nontrivial feedback on cell migration.23,36–38 For example, membrane tension influences the polymerisation rates of the actin network12,39 and is involved in the localisation of regulatory elements, e.g., growth factors and actin-related protein (Arp2/3) complexes.40

As the membrane is very thin (of the order of 4–8 nm compared with typical cell sizes of 20 μm), it is very tempting and intuitive to mathematically describe the membrane as an infinitely thin line, which represents the so-called sharp interface limit (cf. Figure 2a). The coupling to the cell’s interior (cytoskeletal order, flow or elastic fields, etc.) and the distribution of the actin polymerisation rates, for instance, are then captured by appropriate boundary conditions at the interface.

Illustrations of computational approaches and resulting shapes of migrating cells. (a–c) Schematics of the sharp interface, level set and phase-field methods, respectively. (a) In the sharp interface method, a closed curve is advanced with velocity V. The distribution of normal velocities, vn, has to be graded along the curve’s circumference to sustain a steady-state movement. (b) In the level set method, the zero contour of a potential function ϕ determines the position of the interface. (c) In the phase-field method, sharp boundaries between two different phases (here the interior and the exterior of the cell) are approximated by a continuous auxiliary field, the phase field, that smoothly varies across the interface. (d) Examples of propagating cells obtained in the sharp interface limit for different parameter values of the model developed by Casademunt50 (figure reproduced from Casademunt50). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures. (e) Illustration of pseudopod splitting in the course of ameboidal cell migration, obtained by the level set method60 (figure reproduced from Shi et al.60). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures. (f) Morphology of cells for different substrate adhesion strength and myosin contractility, obtained by the phase-field model developed by Shao et al.87 (figure reproduced from Shao et al.87). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures.

Such a description was used by Lee et al.41 to explain the steady motion of simple cells (namely fish keratocytes) via the so-called ‘graded radial extension’ model. This model assumes that the extension of the front and the retraction of the rear of simple cells occurs perpendicularly to the cell edge. Consequently, to maintain steady cell locomotion and a stationary overall cell shape, the actin polymerisation rates have to be graded along the cell’s circumference. The graded radial extension model states that the extension of the leading edge occurs along radii perpendicular to the cell edge at each point. The graded radial extension model led to a number of useful predictions, e.g., on the distribution and orientation of lamella ridges of the extending lamella. However, the model, assuming a fixed cell shape, cannot explain the onset of motion, the emergence of this self-organised dynamics or the selection of the cell’s shape.

Various extensions of the graded radial extension model were implemented in the literature (see e.g., Keren et al.,22 Grimm et al.42 and Kozlov and Mogilner43). Grimm et al.42 incorporated an actin density-dependent extension of the actin network. The ensuing feedback between the density and edge shape results in realistically looking actin distributions for the selected cell shapes. Further refinements included the interplay between the pushing force exerted by actin polymerisation on the cell edges, contractile forces powered by myosin motors and elastic tension in the cell membrane.43 Within the class of admitted cell shapes (circles and discoid fragments), the model exhibits a bistability and hence allows for abrupt transitions from a stationary disc-shaped cell to a moving, crescent-shaped cell. Cell shapes resembling experimental ones can also be reproduced in a model coupling actin network treadmilling and forces resulting from the inextensibility of the cell membrane.22 The best agreement with experiments is obtained assuming a phenomenological force–velocity relation for the lamellopodial actin network,

where V is the velocity of the actin network, f the pushing force, fstall the stall force and V0 is the free actin polymerisation rate (typically, V0 is of the order of tenths of μm per second42). The dependence on force is typically very steep24,44 with exponents around n=8. A more microscopic level of description, taking polymerising actin filaments explicitly into account, was developed by Oelz et al.45. Current extensions of this model are able to reproduce various moving cell shapes.46

Furthermore, many one-dimensional models for moving cells were proposed.31,47,48 Owing to the simpler geometry, such approaches are able to capture more specific aspects of cell migration, e.g., thickness and flow profiles in the lamellipodium,31 the relation between cell velocity, active stress and adhesion strength,47 or the initiation of cell motion via symmetry breaking of the motor-driven flow.48 The question of optimality of (contactility-driven) migration was also investigated.49

An analytical self-consistent approach was proposed by Blanch-Mercader and Casademunt50 to elucidate the onset of motion and two-dimensional shape selection. The time evolution of the membrane position was described by the following simple eikonal equation:50,51

where υn is the normal velocity of the interface, n the normal vector, Vp the actin polymerisation velocity, assumed to be perpendicular to the interface, and v the (viscous flow) velocity of the cytoskeleton. To determine the fluid velocity v in the domain Ω restricted by the cell membrane, certain boundary conditions need to be applied at the cell boundary ∂Ω, e.g., that for the pressure holds , where κ is the curvature and γ the effective surface tension. It was shown50 that under certain model assumptions, the problem can be mapped on the Laplacian growth model, where a number of exact analytic solutions had been obtained.52,53 The model exhibits a subcritical (i.e., abrupt) transition to travelling solutions with various shapes (see Figure 2d).

Models using sharp interfaces are quite intuitive and often provide valuable insights into the problem at hand. In addition—in simplified geometries—they are often amenable to analytic treatment.50,51,54 However, computational implementations of sharp interfaces in two and three dimensions are challenging. Namely, all the fields inside the cell are prescribed on a discrete lattice (e.g., rectangular or triangular), whereas the interface itself is not restricted to any lattice. The moving interface needs to be tracked and interpolated at every time step, which constitutes a nontrivial and time-consuming numerical task. Moreover, the mesh points parametrising the interface tend to migrate along the interface, resulting in numerical instabilities, often calling for remeshing.53 Sophisticated numerical approaches such as evolving surface finite element methods were also developed to deal with this issue.55 Another difficulty with the sharp interface method is that the kinematic condition at the interface is often assumed ad hoc. Such deficiencies can be circumvented by treating the interface implicitly, namely by the level set and phase-field methods described in the following.

Level set method

This approach was originally developed in the context of incompressible two-phase flow.56 In the level set method, the interface is described implicitly, namely as the zero level set of an, in principle arbitrary, function (see Figure 2b). Often this function is chosen as the (signed) distance from the boundary, i.e., , depending on whether one is inside or outside the considered domain. Most importantly, the level set field is advected with the local velocity, according to the corresponding Hamilton–Jakobi equation,

where denotes the local speed in the normal direction of the function ϕ.

The level set method has the advantage of describing ‘featureless’ interfaces, i.e., without interfacial tension or any other physical properties. In contrast, the phase-field method discussed below inherently attributes wall energy—and hence surface tension—to the interface. In practice, however, this difference has a role only in numerical efficiency, as features can be added to the interface in the level set method57 and the wall energy removed from the phase-field method.58 A possible inconvenience that remains for the level set method is that the distance function often is numerically ill-behaved, e.g., steepens in the course of time and accumulates errors. To remedy this deficiency, the level set field typically has to be reinitialised every couple of time steps.

The level set method is nowadays especially used in image analysis, i.e., for cell tracking,59 but has also been used in model development.60–66 For instance, using this method considering different internal cytoskeleton dynamics, the important point has been made that the motility machinery of cells has a certain redundancy: several underlying biological and physical mechanisms (actomyosin contractility; actin polymerisation limited either by G-actin transport or by microtubule-associated vesicle transport; and a model using a simpified regulation mechanism) all can induce cell motility.32 However, the best agreement with experiments is for a certain combination of all these factors. As another example, the level set method was used by Shi et al.60 to model the chemotactic behaviour of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, or human neutrophils (see Figure 2e). The chemotactic behaviour was modelled by coupling different processes observed in chemotactic cells, such as local excitation/global inhibition and actin polarisation, to the interface dynamics. A similar approach has been used later on by Neilson et al.67

For a comprehensive comparison of sharp interface versus level set versus phase-field methods and their implementation in various contexts, we refer the reader to Deckelnick et al.68 and Li et al.69 A systematic comparison of level set versus phase field in a system that is rather close to cells, namely vesicle dynamics in flow, has been recently presented by Maitrea et al.57 While such contrasting juxtaposition highlights the methods’ similarities, technical differences prevail, especially in the way how membrane incompressibility has to be handled.

Phase-field method

The phase-field method70,71 had been originally introduced to model solidification processes, but later on was applied to a diversity of systems including domain growth, microstructure evolution, and structural transformations in materials science,72–74 the Saffman–Taylor fingering instability,58,75 elastic surface instabilities76 and fracture mechanics,77,78 the fluidisation transition in granular media,79 the crystallisation of polymers80 and finally biological systems such as vesicles81–83 (where it also goes under the name ‘advected field approach’) and growing actin gels.84 This list clearly demonstrates the method’s versatility, which meanwhile has developed into a standard tool in the vast field of multiphase/composite materials.85 In its application to cell motility, the phase-field method has been extensively reviewed in Ziebert et al.86

The main idea is the following: instead of tracing the boundary (i.e., the membrane) explicitly, which poses the problems discussed above for the sharp interface models, one uses an auxiliary field to describe the interface implicitly (see Figure 2c). Associated with this field, the phase field ρ(r, t), is a certain ‘free energy functional’ with two local energy minima. The simplest phase-field implementation of an interface is given by the equation

The free energy functional is chosen such that it has a double-well structure with minima at ρ=0 and 1 (cf. Figure 3a). These minima correspond to the two ‘phases’: the inside, defined as ρ=1, and the outside, defined as ρ=0. An alternative way is to use a phase field φ that interpolates between 1 (inside) and −1 (outside), which is also often used.33,81,87 Especially when simulating many cells, the version with ρ=0 outside is better suited. A classical and convenient choice for the free energy density is

Behaviour of the phase-field free energy f(ρ) and bistability in a simple model for motile cells. (a) For the parameter the free energy landscape is such that both phases are in equilibrium (black curve). For one of the phases is preferred: the outside, ρ=0, is preferred for (green curve) and the inside, ρ=1, for (red curve). (b) A stable stationary solution of the minimal phase-field model for a radially symmetric cell. (c) A polarised cell moving with a constant velocity V. Both solutions were obtained for the same values of the model parameters, but evolved from different initial conditions.

In one dimension and for , Equation (4) possesses a stationary solution of tanh form,

(if boundary conditions ρ(−∞)=0 and ρ(∞)=1 are imposed), as known from Ginzburg–Landau theory. The width of the interface hence scales like .

By construction, the value of the parameter δ determines which of the two ‘phases’ is preferred: for both phases have the same free energy and hence a one-dimensional interface (or a planar one in higher dimensions, see below) is stationary (cf. the black curve in Figure 3a). If phase 0 is preferred—it has lower free energy as indicated by the green curve in Figure 3a—and will grow at the cost of phase 1: the cell shrinks or retracts. The opposite is true for , where phase 1 will grow and the cell advances or spreads. In addition to the interface dynamics due to free energy minimisation, the phase field may be advected by a local velocity, , and/or pushed/pulled by forces acting on the interface, , where ζ is a friction coefficient.

In two (or higher) dimensions the dynamics of the interface is affected by the local curvature. This can be illustrated by considering the evolution of a circular two-dimensional ‘droplet’ of radius R that is large compared with the interface width, i.e., . An equation for the radius R can be obtained asymptotically by using the front solution, Equation (6), in polar coordinates (r, θ). Substituting this solution in the form ρ0(r−R(t)) into Equation (4), the solvability condition with respect to ∂rρ0 in polar coordinates yields the following equation (cf. the so-called Maxwell construction88):

If the first term in Equation (7) were not present, one readily recovers the behaviour in one dimension: the droplet shrinks for δ>1/2 and spreads for δ<1/2. The first term is due to the inherent presence of a surface tension Σ, stemming from the free energy associated with the interface. This apparent surface tension can be defined as the excess energy due to the interface, yielding (wall energy in Ginzburg–Landau theory).

Note that in the context of cells, this surface tension is not related to membrane tension. It rather is an ‘artefact’ of the phase-field approach, which however can be removed in first-order approximation by subtracting a term, with χ the interface curvature, from the phase-field equation, see Folch et al.58 and Biben and Misbah.81 For a more detailed discussion of membrane tension effects in phase-field models for cells we refer to Winkler et al.38

With the interface defined implicitly, and the coupling to flows and/or forces described above, one has all the building blocks at hand to model and investigate motility mechanisms for cells. As an example, a kind of minimal model was developed by Ziebert et al.,34 by coupling the phase field to a single equation for the vectorial mean orientation of the actin filaments (see below, Equations (11) and (12), for details). This was enough to, for instance, recover the bistability of keratocyte fragments19 as shown in Figure 3b,c: round cells do not exhibit motility; however, if stimulated, cells polarise, assume a crescent-like shape and undergo persistent directional motion. The recent progress by phase-field models in the context of moving cells is reviewed in detail in the next section.

Other computational approaches

A variety of other computational methods were used to study certain aspects of moving cells, both individual ones and confluent layers (cf. the recent review presented in Holmes and Edelstein-Keshet89).

For instance, the immersed boundary method was used to model ameboidal cell motility in Bottino and Fauci.90 The immersed boundary method was originally developed to simulate fluid–structure interaction,91 the fluid being represented in Eulerian coordinates and the structure (e.g., an elastic surface mimicking the cell membrane) in a Lagrangian coordinate system. The structure is then approximated by a collection of one-dimensional fibers with a certain prescribed force distribution that feeds back on the fluid. Using interpolation methods between the two grids then allows to evolve the system in time. Using this technique, directed locomotion of a model amoeba was obtained.90 The immersed boundary method is especially suited for objects immersed in a single fluid, e.g., for vesicles or for swimming deformable bodies.92 For crawling cells, however, the motility-induced viscous drag outside is typically small compared with the substrate-based propulsion forces and the viscous dissipation inside the cell.

The cellular Potts model (CPM), on the other hand, is a popular lattice-based algorithm developed to simulate the dynamics of various cellular structures,93 such as foams, biological tissues or confluent layers of motile cells.94–96 In the CPM, each lattice site is updated based on a set of probabilistic rules, similar to Monte Carlo methods. These rules have (typically) three components: (i) first, a lattice site is selected for a putative update; (ii) a certain Hamiltonian or free energy is then evaluated to accept or reject the update step; (iii) additional rules are invoked to introduce specific ‘biological features’, e.g., cell sorting, division or cell motility. The CPM technique is very efficient for confluent layer dynamics, e.g., for cell colonies rotating on an adhesive patch94,95 or for cells on more complex adhesive patterns.96 However, the underlying dynamics of CPM is rather artificial. The method also becomes computationally expensive when applied to single-cell motion, since then it typically requires updates of unoccupied sites.

Phenomenological approaches, based on a dynamics of the distance of the boundary to the cell’s center, were recently developed as well. For instance, a model coupling cell adhesion with protrusion was proposed in Stéphanou et al.97 and allows to reproduce several aspects of fibroblast migration. The model is formulated in terms of a one-dimensional equation along the cell cortex, and accounts for the actin concentration at the cortex, the width of the cortex annulus, the resistive elastic stress due to the cortical network–membrane attachment and especially for adhesion maturation. A minimal model of spontaneous polarisation and edge activity was recently introduced by Raynaud et al.98 There the crucial model assumption is that the switching probability of the cell edge from an advancing to a retracting state (that was measured experimentally) depends on the distance from the cell center. This model can reproduce spontaneous polarisation, migration and even the rotation of a cell displaying several lamellipodia, as recently observed in experiments.98,99

Other approaches are inspired by the recent insights gained from general theories of self-propelled particles. One such approach is based on the idea to develop dynamic equations directly for the shape, i.e., the shape deformation modes, and was recently used to study the collective dynamics of multiple deformable self-propelled objects.100–102 Typically, for simplicity only few modes of the shape deformations are permitted (e.g., up to quadrupolar). Nevertheless, the approach reproduced several aspects of collective cell migration, such as the onset of orientational order, or oscillatory and spinning motions. Finally, a model of interacting and dividing self-propelled particles was used in the context of wound healing.103 The key assumption there was the tendency of a single cell to align its motility force with its velocity. Consequently, the motility forces of the cells inside the tissue tend to align with the flow that is created owing to cell division. Under certain conditions, the modelled growing cell tissues exhibit collective dynamics, as well as fingering-like behaviour, similar to that observed experimentally.104

Recent progress with phase-field-based approaches

Active gel droplets

Active gels are in vitro systems formed by a network of crosslinked filaments (microtubules, actin) subject to the action of molecular motors converting chemical energy (of adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis) into mechanical work.105,106 Another recent realisation of an active gel are motile bacteria suspended in a lyotropic liquid crystal.107 First theories of active gels were formulated by extending the macroscopic Landau–de Gennes approach for liquid crystals to a nonequilibrium situation.108,109 More recent approaches are based on microscopic interactions. Namely, a set of minimal equations for coarse-grained variables (such as concentration, polarisation and nematic order parameter) was derived from a Vicsek-type model for interacting particles via an asymptotic truncation of the corresponding Boltzmann equation.110,111

Droplets encapsulating active gels exhibit many features of living cells, such as spontaneous symmetry breaking, polarisation and sustained self-propelled motion.106,112 As active droplets are formed from a rather small number of well-characterised constituents (filaments, motors, crosslinks, adenosine triphosphate, buffer), such biomimetic systems open intriguing possibilities for in-depth explorations of ‘artificial cells’ with the propensity to move and possibly divide. Active gel droplets are closely related to even simpler synthetic systems, namely self-propelled droplets that are driven, e.g., by a gradient of surface tension,113 adhesion gradients114 or interfacial chemical reactions.115 For a recent review on such ‘swimming’ droplets we recommend Maass et al.116

While the physical and biological processes responsible for the motility of active gel droplets are obviously not the ones of living cells, further studies of active gel droplets very well may yield important insights into the generic mechanisms of, for instance, spontaneous symmetry breaking, onset of polarisation and collective migration. As they are in many aspects much simpler than living cells, their behaviour potentially can be explored in a much wider range of experimental conditions and one may hope to develop a predictive mathematical description of their behaviour (which still remains distant for cells).

Computational studies of the movement of single active gel droplets were performed.117–119 There it is assumed that the droplet contains some sort of ‘active gel’ material that can be described by a polarisation vector p (or alternatively by a tensorial nematic order parameter Q). The evolution of the polarisation field p follows an equation for polar liquid crystals,120,121 generalised by active reactions108,109 and coupled to the hydrodynamic flow field v (cf. Marth et al.117 and Tjhung et al.118).

Here and are the vorticity and rate of strain tensors, respectively, ξ describes the flow alignment of the polarisation, Γ is proportional to the rotational viscosity, ω is a mobility and Fp is the Ginzburg–Landau–de Gennes free energy functional describing the relaxational dynamics of the polarisation p. The term ω p models the propulsion of polar matter in the direction of the polarisation vector.

The flow v is obtained from the Navier–Stokes equation117

where Re is the Reynolds number, p the hydrostatic pressure and σ the stress tensor. For most practically relevant situations the Reynolds number can be set to zero, and the Navier–Stokes equation reduced to the Stokes equation. In addition to standard stress contributions in (polar) liquid crystal theory,120,122 the stress tensor contains an ‘active stress’,108

that describes, e.g., the contraction of the actin network by myosin motors. Note that such a contribution is not present in equilibrium theory of liquid crystals. Finally, the order parameter (phase field) ρ follows an evolution similar to that of Equation (4), coupled to the polarisation and flow fields p, v (see Marth et al.117 and Tjhung et al.118 for details). We would also like to note that active gel equations have to be developed carefully, concerning thermodynamic consistency.123

Numerical studies of the active droplet (Equations (8, 9, 10)) revealed the onset of spontaneous polarisation and sustained self-propelled motion (see Figure 4a). Once the droplet is set into motion, the polarisation field p assumes a characteristic ‘splayed’ orientation. This splayed configuration, the hallmark of motile droplets, is needed to break the axial symmetry of the system. The flow field v, in turn, exhibits two counter-rotating vortices inside the droplet. Note that this flow field is determined, in part, by the confined geometry, as it is similar to that in much simpler motile droplets, driven by surface tension gradients.113 A similar motile behaviour is also observed for droplets filled with an ‘active nematic’ material.119 In that situation, the polarisation field is absent in the homogeneous system and only the tensorial nematic order parameter Q prevails. One may argue that a heterogeneous distribution of the nematic order parameter Q is the common feature relating the approaches of Tjhung et al.118 and Giomi and DeSimone:119 namely, a heterogeneous Q generates an effective polarisation vector,110 via . Indeed, as for the polar case described above, the moving droplet establishes a splayed configuration of the polarisation field.

Phase-field modelling of active droplets and single cells. (a) The actin orientation (upper panel) and actin flow velocity (lower panel) for a droplet filled with an active polar liquid crystal.117 The actin orientation displays a splayed conformation, and the flow in the laboratory frame exhibits two counter-rotating vortices. The green arrow indicates the direction of motion (figure reproduced from Marth et al.117). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures. (b) The actin distribution and the traction force exerted on the substrate of a crawling cell.126 Motion is to the right. The black solid curves show the contour at phase-field level ρ=0.25. The internal actin orientation p and the traction T are shown by arrows, respectively. Red (blue) corresponds to large (small) values of the phase field and the traction force, respectively. (c) The distribution of actin density (upper panel) and myosin motors (lower panel) for a crawling cell as modelled by Shao et al.87 (cf. Figure 1b). Motion is upwards. Color code: Red (blue) corresponds to maximum (minimum) values (figure reproduced from Shao et al.87). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures. (d) Sequence of snapshots illustrating an adhesion front and the cell’s deformation during a stick-slip motion cycle.125 Motion is to the right. The cell boundary is shown in green, and arrows indicate the local actin polarisation. White color corresponds to zero adhesive bonds, A=0, blue to A=0.5 and red to A=1 (saturated adhesion). (e) Demonstration of motility by actin polymerisation waves.132 The inset displays the trajectory of the cell’s center of mass. The green contour shows the phase-field level ρ=0.05, white arrows indicate the polarisation p and colors (again from blue to red) the actin density.

Minimal model for a single cell

A minimal phase-field model that displays a subcritical onset of motion and realistic cell shapes was formulated by Ziebert et al.34 The model has only two dynamic variables: the phase field (or order parameter) ρ, describing the cell’s deformable and movable shape, and the average orientation (polarisation) of the actin network p. It can be written as a system of two coupled partial differential equations

Here Dρ determines the width of the interface and mimics the cell’s surface tension (see discussion in the previous section). The last term accounts for the pushing force exerted by the cytoskeleton on the cell’s boundary, with an effective velocity (force over friction coefficient with the substrate). The friction, in turn, depends on the density of adhesive ligands A, linking the cytoskeleton to the substrate. For simplicity we here assume ; extensions to the case of adhesion dynamics are considered later. Unlike in active gel droplets, the polarisation dynamics is considered to be enslaved to the order parameter ρ: it is driven by the phase-field gradient, i.e., the term , with β being proportional to the actin polymerisation velocity (of the order of 0.1 μm/s). This form of coupling, with the membrane position (having high ∇ρ) being a source term for p, is motivated by the fact that the actin network is predominantly growing at the cell membrane, where growth factors such as Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein and Arp2/3 protein complexes are located.3,4 In the p equation, a diffusion (or elastic) term DpΔp is included. The term describes degradation of actin, e.g., via depolymerisation, with a rate . The time scale is of the order of the actin turnover time, typically tenths of a second. The term explicitly suppresses p outside the cell (note that, as the phase field is zero outside the cell, nonzero values of p there do not affect the dynamics). Advecting the polarisation field with the local velocity, as in Equation (8), could be implemented instead, but is computationally more expensive.

As the order parameter (Equation (11)) does not conserve the cell area (cf. the discussion in the last section and Equation (7)), it needs to be supplemented by an area conservation constraint (or volume conservation in three dimensions). The easiest implementation is via the parameter δ governing the phase-field free energy, as a global constraint:

Here μ is the stiffness of the constraint and the term within parentheses is the difference between the cell’s current area and the prescribed (i.e., initial) area V0. If, for instance, the cell is too small, the resulting will lead to a growth of phase ρ=1 (cf. the red curve in Figure 3a), and hence the cell will expand to restore the area V0.

So far, all the terms discussed are perfectly symmetric. For the cell or cell fragment to be able to sustain stable polarised states that can move, the symmetry has to be broken. Two mechanisms, both related to molecular motors, were implemented by Ziebert et al.34 based on the experimental evidence for fish keratocytes:7 first, the term in Equation (11) accounts for the contraction of actomyosin. It can be motivated by active gel theory,17,108 predicting a stress of the form given by Equation (10). In this respect, corresponds to the principal value of the active stress tensor and describes actin contraction by motors with a rate σ, a description that could be still refined by accounting for the stress field explicitly. Second, the last term in Equation (12), , accounts for motor-induced actin bundling at the rear, as observed for keratocytes.7,19 This term, which can be motivated by a simple motor dynamics,34 describes an increased motor activity at the rear that suppresses the polarisation p (as a contractile bundle favors antiparallel actin filaments). This term explicitly breaks the ±p reflection symmetry and stimulates self-polarisation.

The numerical study of Equations (11) and (12) recovered the subcritical onset of motion—in accordance with the experiments on cell fragments19,30—and a variety of shapes closely resembling those of moving keratocytes: Initially round cells remained stationary (cf. Figure 3b). However, for the same parameter values, cells with an initially nonsymmetric distribution of polarisation (e.g., due to stimulation) transformed into a crescent shape object moving with constant speed (cf. Figure 3c). The velocity depends on the model parameters, and increases with α and β, related to actin ratcheting/polymerisation rate. The analysis also shows that the velocity dependence on parameters is not continuous. Rather, a minimal velocity exists, below which steady propagation is impossible. Equally important, either the contraction parameter σ or the parameter γ mimicking the bundling at the rear (or both) must be sufficiently large to make motion possible, i.e., the symmetry must be strongly broken by the action of molecular motors. Finally, σ also largely controls the cell’s overall shape: for small σ values the cells assume a tadpole-like shape reminiscent of a fibroblast, and for large σ values the cells become crescent-like.

A conceptually similar but more complicated phase-field formulation of cell motility was developed by Shao et al.33 Instead of a single polarisation field p that also captures the local actin orientation, two phenomenological fields for crosslinked actin filaments and actin bundles, respectively, were introduced implying different actin protrusion/retraction forces. The model also reproduced motile states and a variety of cell shapes. Overall, the similarity in the cell’s behaviour obtained by the quite different phase-field approaches of Ziebert et al.34 and Shao et al.33 implies that basic phenomena of polarisation and shape selection are rather robust, i.e., not too sensitive to the details of description, as already pointed out in Wolgemuth et al.32

Cell-substrate interaction and other model refinements

The minimal model just discussed can be extended in a modular way, including additional physical and biological processes and feedbacks. Cell-substrate interaction is a multistage process involving interactions of several proteins forming complexes that link the cell’s internal actin cytoskeleton to the substrate (e.g., extracellular matrix or synthetic ones covered with adhesive ligands). The adhesive system is mechanosensitive, i.e., the formation of adhesive bonds depends on forces, both self-generated internally by the cells or stemming from external sources (other cells, inhomogeneous substrates). Depending on the time scale of motion, nascent adhesion sites may also undergo maturation, i.e., transformation from transient adhesion points into strong, stress-fiber-bound focal adhesions. For a recent review on the physics of cells on substrates we refer to Schwarz et al.15 A detailed study of the (much simpler) adhesion process of vesicles on surfaces, modelled by the phase-field approach, was carried out by Zhang et al.124

A continuous equation for the density of the formed adhesive bonds, A, describing a generic attachment–detachment kinetics was proposed and coupled to the minimal phase-field model:125

The first term describes the diffusion of the membrane proteins forming the adhesive complexes (such as integrins). The second term describes two attachment mechanisms, both restricted to the inside of the cell by the common factor ρ: a constant (A-independent) attachment rate that is proportional to , implementing the necessary presence of actin to build an adhesive bridge with the substrate. Second, an attachment term that is nonlinear in A and phenomenologically models mechanisms facilitating the attachment of additional bonds if a bond has been already formed (like local reduction of membrane fluctuations). The last term, , contains the two dominant contributions that limit the number of adhesive bonds: (i) detachment, with a rate d that depends on the substrate deformation u; (ii) a term that is cubic in A and limits the total number of adhesive bonds at a given place (excluded volume).

The feedback of adhesion to the cell’s dynamics can be naturally implemented by the adhesion-dependent protrusion force (cf. Equation (11)). The cell’s mechanosensitivity, in turn, can be captured by two more ingredients. First, by a dependence of the detachment rate d(u) on the substrate displacement, u(x, y; t). A step function d(u)=d0θ(u−Uc), where θ(x⩾0)=1, θ(x<0)=0, could be assumed for simplicity. For numerical purposes a smoothed version (with b≫1 a smoothing factor) is more convenient, . Here the parameter Uc determines the critical displacement for the rupturing of the adhesive bonds, and d0 the maximum rate of detachment.

The second ingredient relates to the traction force, T, the cell exerts on the substrate it is spreading or crawling on (cf. Figure 1d). The substrate displacement u(x, y; t) can be obtained by solving the corresponding three-dimensional linear (visco)elasticity equation with appropriate boundary conditions. This solution is computationally expensive, and leads to a nonlocal coupling between the fields. To leading order in the thickness, h, of the viscoelastic layer (i.e., adhesive complexes plus extracellular matrix) sandwiched between the cell and a rigid surface, the corresponding equations can be reduced to126

Here G is the effective elastic (shear) modulus of the substrate and η describes dissipation in the adhesive process, e.g., due to bond rupturing. To obtain a closed description, an expression for the traction distribution T is needed. A possible closure is to assume that the cell’s propulsion force is like , with ξ a coefficient characterizing the efficiency of force transmission. The propulsion force is balanced by the friction force Ffric, which is proportional to the density of adhesive ligands A. Since a self-propelled cell is a force-free object, the total traction must be zero, . This condition then uniquely defines the traction distribution.126

The computational model given by Equations (11), (12), (13), (14), (15) successfully reproduced many features exhibited by moving cells, such as qualitatively correct distributions of actin polarisation and traction forces for keratocyte-like cells (see Figure 4b). In addition to steady cell migration, a variety of complex dynamic propagation modes were discovered, including stick-slip motion125 (see Figure 4d) and even bipedal motion.126 Stick-slip movement is characterized by periodic attachments/detachments of the cell and strong modulations of the propagation speed and shape of the cell. Qualitatively similar behaviour were found for lamellipodia, displaying periodic contractions that depend on the adhesiveness of the substrate,127 osteosarcoma cells,128 as well as in filopodia.129 Bipedal motion, where the cell sides oscillate back and forth normal to the direction of motion in an out-of-phase manner, has been also experimentally found in keratocytes.130

Various refinements of such modelling approaches are possible. Most importantly, the traction distribution T can be obtained in a more detailed, and more microscopic, way via a force-balance condition at the substrate,87 incorporating stresses produced by molecular motors, polymerising filaments, adhesion and membrane forces, as well as viscous stresses due to flow of actin. The model presented in Shao et al.87 then reproduces a variety of cell shapes closely resembling experimental ones (see Figure 2f), as well as the distributions of actin and myosin within a crawling cell (cf. Figure 4c). In qualitative agreement with the experiments, actin is accumulated at the front of the moving cell, and myosin at the rear. The approach, however, computationally is significantly more expensive than the one given by Equations (11)–(15): one of the major computational difficulties is the temporal evolution of the actin flow field that has to stay confined inside the moving cell. In Shao et al.87 this was carried out iteratively by an implicit relaxation scheme. This rather high numerical cost limits the approach of Shao et al.87 and Camley et al.131 to relatively small systems and short simulations times.

Membrane tension may also provide a feedback on shape and motility of migrating cells. It was found38 that the most important effect is the membrane’s counteracting force on actin polymerisation. In contrast, bending rigidity has only minor effects on the shape and migration speed, and is relevant only in reshaping events.38

The phase-field approach can also be applied to cells exhibiting ameboidal motility, such as neutrophils or the social ameba D. discoideum.132 The motility mechanism for these cells is not due to tightly controlled actin ratcheting close to the membrane, but rather relies on spontaneous actin polymerisation waves regulated by certain nucleators.133 Coupling a model for actin polymerisation waves to the phase field, in addition to directionally migrating cells, more complex motility modes were observed: erratic ameboidal cell crawling and rotational motion as shown in Figure 4e, as well as run-and-tumble motion.132 The phase-field approach was also recently applied to model neuronal growth.134

Finally, the effect of a simplified signalling pathway on cell motility has been investigated within a phase-field approach in Marth and Voigt.135 There a classical Helfrich-type description for the cell membrane136 was coupled to a simplified biochemical network model for the activation of GTPase. The system of equations was solved by an adaptive finite element method and a variety of cell shapes and modes of migration were obtained, including steady migrating cells and the formation of filopodia-like structures. The response of cells on various spatiotemporal signals, e.g., rotating stimuli, was also studied within this approach.135

Cell movement on spatially modulated substrates

Modulations of substrate properties, such as adhesiveness and/or stiffness, have a strong effect on cell movement. The natural environment of cells is typically quite heterogeneous, as it is formed by other cells, tissues or extracellular matrix, displaying different elastic and surface properties, as well as adhesiveness. Also for technological purposes (cell sorting and guiding) and studies of cellular response, it is more promising—and easier—to study cells on substrates with designed properties, rather than to change the cell’s internal biochemistry.

The substrate adhesiveness, for instance, can be varied by grafting high densities of adhesive ligands on some parts of the substrate while passivating other regions (i.e., making them only weakly adhesive or even repellent). State-of-the-art microcontact printing techniques currently allow to engineer almost any adhesive pattern on the micron scale.25,137 Unfortunately, it is much more difficult to vary the density of ligands in a quantitative manner. The substrate stiffness can nowadays also be modulated, either in a step-like manner via fabrication of microposts by soft lithography138 or in a smoother manner,139 by controlling the crosslink density of the substrate’s polymer network.

Various approaches have been applied to address cell migration on micropatterns, see the recent review.140 Obviously, the phase-field approach is ideally suited to study cell movement on modulated substrates, as no tracking of the cell’s boundary is needed and the cell’s shape is accounted for self-consistently. Consequently, the main phenomenology found experimentally could be captured by computational phase-field models.125,126,131 Figure 5a illustrates cell migration over a substrate exposing stripes of alternating high/low adhesiveness. This situation had been studied experimentally for keratocytes in Csucs et al.25 using microcontact-imprinted stripes of fibronectin (corresponding to regions of high adhesiveness) and of poly-L-lysine-polyethylene glycol block copolymers (practically nonadhesive). In the phase-field description just described, such a modulation of the substrate adhesiveness can be modelled by a spatial modulation of the formation rate of adhesive bonds, a0, in Equation (14). The upper panel of Figure 5a shows the case of stripes with large values of a0. In excellent agreement with the experiments,25 the simulated cell positions itself symmetrically with respect to the stripes and migrates along them.125 Moreover, the leading edge of the cells exhibits ‘protrusion bumps’ on the stripes with high adhesiveness and ‘lagging bumps’ on the stripes of low adhesiveness, again in close agreement with experiment. The lower panel of Figure 5a shows a cell moving on a substrate with a lower value of the adhesion parameter a0. Initially, the cell was stimulated to move along the stripes. However, a fundamentally different behaviour is observed after some short transient:125 the cell slowed down, abruptly changed its direction and started to move perpendicularly to the stripes. The cell also tried to spread along the stripe, to maximize contact with the region of higher adhesiveness. For intermediate values of the parameter a0, a combination of these two modes of motions was observed, i.e., the cell alternated between moving along and perpendicularly to the stripes. Center of mass trajectories for all three cases are shown in Figure 5a.

Cell guidance by modulation of substrate properties. (a) Navigation of cells on a striped substrate with alternating high (blue) and low (black) adhesiveness.125 If the adhesiveness is strong, the cell migrates along the stripes (upper panel). If the adhesive strength of the stripe is decreased, the cell switches to a stick-slip motion and migrates normal to the stripes (lower panel). The right panel displays cell trajectories for different adhesive strength of the stripes: for high adhesiveness the cell migrates along the stripes, with the cell centroid located in the middle of the stripe (black curve), for low adhesiveness the cell moves back and forth perpendicular to stripes (red curve), and for intermediate adhesiveness (blue curve) a combination of two regimes is observed. (b) Cell trajectories and cell shapes for stripe patterns with different width ratios of adhesive versus nonadhesive stripes.125 Cells move along wide adhesive stripes (black curve and lower right image). For intermediate widths, the cells migrate substantially across the stripes (red curve and upper image). For even smaller widths, the cells stretch in and again move along the stripes (green curve and lower left image). (c) Cells encountering a step-like change in the substrate stiffness (blue marks a stiff, black a soft substrate). Depending on the incidence angle and the propulsion parameters, the cell is either scattered, moves along the step, is crossing the step, or is reflected.126 (d) Demonstration of durotaxis: shown are trajectories of cells that were launched at different positions on a substrate displaying a stiffness gradient in y direction (again blue is stiff, black is soft). All trajectories converge to a y position with a ‘preferred’ stiffness.126

When microcontact printing adhesive stripes, is is easier to vary the relative width of the (adhesive versus nonadhesive) stripes than to quantitatively change the density of the adhesive ligands in the two regions. Three different types of cell motility were observed for different stripe width ratios125 (see Figure 5b): cells moved along the stripes if the adhesive stripe width was relatively large. A gradual decrease of the stripe width triggered an instability: the cell exhibits a kind of ‘rocking motion’ (similar to bipedal motion), and turned perpendicular to the stripes. The motion was associated with random reversals of direction, similar as on substrates with low adhesiveness discussed above. Finally, upon further decrease of the adhesive stripe width, the reverse trend was observed again: the cell stretched out in the direction of motion to fit between two stripes, and moved again along the stripes. A still open issue here is the effect of commensurability between the size of the cell and the period of the adhesiveness modulation.

While microcontact printing allows to create almost arbitrary adhesiveness patterns, such chemically structured surfaces are often not very robust and are prone to degradation. Substrates with modulated mechanical properties (mostly stiffness) are more stable in this respect and equally relevant to model heterogeneous biological environments. A variety of experimental approaches are currently explored to design soft synthetic surfaces with desired mechanical properties. Stiffness variations can be implemented via soft microfabrication of arrays of microposts (or pillars) of different dimensions (height, thickness).138 Other approaches include fabrication of gradient materials with gradually varying elasticity via gradually controling the crosslinking density141 or composite materials with alternating stiffness patterns.142

In the phase-field model discussed here, stiffness modulations can be introduced125,126 by spatially varying the effective elastic module G of the substrate in Equation (15). Figure 5c illustrates the behaviour of cells encountering a step in the substrate stiffness: if cells are moving towards a step from a soft substrate (shown as black) to a stiffer one (blue), the cell typically can pass the step; if it hits the step at a certain angle, it may change its propagation angle. Cells moving towards a softer substrate may either be reflected back or becoming trapped and begin to move along the step. This behaviour is consistent with experimental observations of fibroblast cells on micropost assays,138 where the majority of the cells preferred to stay in the area of high stiffness and cells coming from the softer side often rotated and then migrated perpendicularly to the stiff substrate.

Figure 5d shows trajectories of cells on a substrate displaying a linear stiffness gradient in y direction.126 These simulations show that cells prefer to stay (and to move) on a substrate with a certain ‘optimal’ stiffness: on very soft substrates, the cells migrate towards stiffer regions, whereas on very stiff substrates, the cells move towards softer areas, and hence all cell trajectories converge. This behaviour is consistent with the basic features of ‘durotaxis’, found experimentally already some time ago.139

Collective migration of multiple cells

Despite significant advances in understanding the mechanics, biochemistry and dynamics of individual cells, collective cell behaviour and motility still is an open area of research. Most of the experimental works are focused on the dynamics of confluent layers, predominantly in the context of would healing.143,144 There are also studies of collective behaviour in small cell groups on adhesive patches145 and recently of collective cell migration confined on adhesive domains.94,137,146 Earlier, collective behaviour of keratocyte and canine kidney cells in unbound domains was studied.28,147–149

Quite recently, significant progress in modelling and understanding of collective behaviour of multiple cells was achieved using phase-field methods.150–154 If every cell has to be resolved in some detail, current computing power allows to study the dynamics of up to about hundred cells. A first phase-field model of multicellular systems with several (nonmotile) cells was developed in Nonomura,150 by associating a separate phase field to each individual cell. In such an approach, steric or excluded volume interactions between the cells can then be easily introduced, by adding to the individual phase-field equations terms penalizing cellular overlaps, e.g., by introducing a repulsive binary interaction potential of the form

that is large and positive if the cells overlap, and zero if not. Here is a parameter determining the interaction strength and m, n are arbitrary positive exponents. The simplest case, m=n=2, was chosen in most of the works, and the dynamic behaviour appears not to be very sensitive to the specific choice of the potential W2. Similarly, cell–cell adhesion can be implemented via coupling phase-field gradients (see Ziebert et al.86 and Löber et al.153 for details).

In Nonomura,150 the dynamics of each cell, in turn, was based on the minimization of surface area and volume conservation. In addition, cell–cell adhesion and excluded volume interactions between different phase fields were included. A two-dimensional version of the model was used to study the dynamics of cell cultures with dividing cells, and a three-dimensional model was applied for understanding the response of cell clusters under external forces.

In an attempt to isolate the role of elasticity mismatch on cancer cell migration, a phase-field description of a confluent monolayer containing both healthy and cancerous cells was developed in Palmieri et al.151 Again each cell was described by an individual phase field, and had a self-propulsion velocity vi assigned to it. For simplicity, it was assumed that all cells have the same absolute value of velocity, , but the orientation of each cell’s migration direction was changed according to a certain random process. Using this dynamics demonstrated that the elasticity mismatch between healthy and cancerous cells can considerably increase the effective motility of the—much softer—cancerous cells.

A more detailed phase-field model for a pair of endothelial cells rotating on a small adhesive patch was developed by Camley et al.152 (see Figure 6a). The model accounted for the cells’ internal chemical polarity, as well as for excluded volume and adhesion interactions between the cells. Multiple mechanisms were examined concerning their effects on the cells’ collective rotation, including contact inhibition of locomotion, as well as neighbour alignment and velocity alignment (i.e., the alignment of cell polarity and velocity, respectively). It was established by extensive simulation studies that even small differences in the polarity mechanisms strongly affect the collective rotation. The latter also was affected by taking the cells’ nucleus (modelled as an additional phase field) into account: including the nuclei into the description led to more robust rotations.

Collective cell behaviour. (a) A sequence of images illustrating the persistent rotational motion of a pair of cells on an adhesive spot (dashed rectangular region). The black curves show the cell membrane, the red curves high levels of Rho GTPase and the nuclei are shown in blue (figure reproduced from Camley et al.152). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures. (b) Collective motion of cells on a double periodic domain.153 The yellow arrows indicate the current directions of migration, contours of the cells are shown in white, the absolute value of the actin orientation |p| in blue and regions with high density of adhesive bonds, A, in green. (c) Collective rotation of cells inside a circular adhesive domain.153 (d) Dynamics of an almost confluent layer of cells in a circular adhesive domain. Cells compete for voids and execute random walk-like motion, as depicted by select trajectories of individual cells.153 (e) Formation of tissue-like clusters of cells for high cell–cell adhesion.153

The collective migration of a rather large population of cells (up to a hundred) on open (double-periodic) or circular domains was recently studied by Löber et al.153 (cf. Figure 6b–e), with the individual cell dynamics described by Equations (11)–(15) augmented by excluded volume interactions and cell–cell adhesion. The resulting collective migration in a double periodic domain—and in the absence of cell–cell adhesion—is shown in Figure 6b. Initially, the cell polarisations (and, hence their migration directions) were distributed randomly, which caused them to collide multiple times. Each collision resulted in a velocity alignment, i.e., the cells effectively collide inelastically for the chosen parameters. After a certain transient, i.e., sufficiently many collisions, all cells migrated in the same spontaneously chosen direction. This behaviour is reminiscent of the flocking transition, emerging in the Vicsek model of self-propelled point particles,155 as well as in systems of colliding self-propelled inelasic disks.156 On a large circular domain, a similar behaviour was found: after sufficiently many collisions, the cells began to rotate in a spontaneously chosen direction (either clockwise or counterclockwise) (see Figure 6c).

To quantify the flocking behaviour of collective motion, order parameters can be introduced. For the translational collective motion, one possibility153 is to choose

where is the normalized velocity vector of the ith cell. For large cell numbers, the order parameter will vanish if the velocity orientations are randomly distributed, and it will tend to be one if all cell velocities are aligned. Analogously, an order parameter ϕR for rotational collective motion can be introduced, e.g., via a projection of the velocity on the angular unit vector.153 The red curves in Figure 7a,b illustrate the onset of collective cell migration corresponding to the systems shown in Figure 6b,c. After a transient reflecting the alignment process by inelastic collisions, both order parameters approach the value one. The blue curves in Figure 7a,b characterize the behaviour of the same systems but for cells experiencing moderate cell–cell adhesion. One may expect that cell–cell adhesion, promoting formation of aligned moving clusters, will amplify the trend towards collective migration. In contrast, collective behaviour is suppressed as shown by the order parameters fluctuating around zero. The reason is that rather than stable collectively moving states of many cells, randomly moving, short living and continuously merging and breaking clusters of few cells are formed. This behaviour is consistent with the dynamics of Vicsek models that include attractive (cohesive) interactions.157

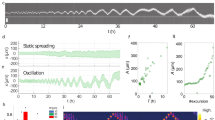

Order parameters for translational and rotational collective motion. (a) Order parameter153 for translational motion, ϕT, as given by Equation (17). The red curve illustrates the onset of translational motion with cell–cell adhesion absent (cf. Figure 6b). In contrast, the blue curve displays the order parameter for cells experiencing moderate cell–cell adhesion, and collective motion is suppressed. (b) Order parameter for rotational collective motion, ϕR (see Löber et al.153 for details). Again the red curve illustrates the onset of rotational motion without cell–cell adhesion, as shown in Figure 6c, and the blue curve the suppression of this effect due to moderate cell–cell adhesion.

The model developed by Löber et al.153 was also studied for higher cell ‘packing fractions’: the dynamics in an almost confluent layer of migrating cells, confined on a circular adhesive patch, is shown in Figure 6d. For such large filling fractions, the dynamics is characterized by random-like movements of the cells, competing for voids within the crowded environment: individual cells ‘rattle’ in their ‘cages’ formed by the other cells, followed by abrupt escapes and larger-scale excursions (see the select trajectories in Figure 6d). For high cell packing fraction and very high cell Löber et al.cell adhesion strength, the cells may gather in travelling bands (‘phalanges’, see Löber et al.153), or form hexagonal tissue-like structures that are mostly stationary, with moving cells and patches outside and at the boundary of this ‘tissue’ (see Figure 6e).

Recently, Marth and Voigt158 generalised the description of active droplets towards a multiphase-field description of many droplets, including hydrodynamic interactions. The results on collisions and collective behaviour are quite comparable to those found in the multicell model.153 A phase-field model for collective cell migration was also proposed by Najem and Grant.154 Similar to the approach by Löber et al.,153 the model is based on a Ginzburg–Landau free energy formulation and incorporates adhesion, surface tension, repulsion, mutual attraction and polarisation of cells. The model predicts a density threshold for cell-sheet formation.

Three-dimensional model of cell migration

Full three-dimensional modelling of cell movement in a heterogeneous three-dimensional environment is a formidable numerical task. Up to date, three-dimensional phase-field models were developed for nonmigrating cells,150 and for migrating active gel droplets,159 extending the approach developed by Tjhung et al.118 to three dimensions. In Tjhung et al.,159 the cell was represented by a droplet of contractile active fluid with treadmilling (i.e., polymerisating actin, described by the polarisation vector p) confined to a thin layer near the substrate. Nearly radially symmetric treadmilling distribution causes the droplet to spread. It assumes a ‘fried egg’ shape resembling that of a stationary keratocyte.159 Similar to the two-dimensional case,118 crawling droplets emerge as a result of spontaneous symmetry breaking. The model shows a variety of shapes and/or motility regimes, some closely resembling cases seen experimentally: Figure 8a,b illustrates a slug-like cell shape, and a cell displaying lamellipodium-like motion, correspondingly. Overall, this work illustrates that also in three dimensions cell shapes can be determined by generic robust physical mechanisms that are not very sensitive to (cell-specific) biochemical regulation pathways.

Three-dimensional shapes of crawling cells. Some of the shapes captured by the three-dimensional phase-field model proposed by Tjhung et al.159 (a) A slug-like cell, resulting for low contractility and no surface anchoring of the actin polarisation to the droplet’s surface. (b) A keratocyte-like cell obtained for stronger contractility and surface anchoring (figure reproduced from Tjhung et al.159). Permission has been granted by the publisher to use the original figures.

Future directions and outlook

In this work, we surveyed a variety of computational approaches to cell motility. Our main focus was on the phase-field method, where most of the recent advances were achieved. One of the important advantages of the phase-field approach is its circumventing of major numerical and conceptual bottlenecks associated with the tracking of boundaries in two and three dimensions. Further on, the phase-field method can be extended in many directions, and, importantly, in a modular manner.160 As shown here, intracellular mechanisms such as actin (retrograde) flow,87 polymerisation waves,132 chemical signalling60 and regulation,117, and also effects of the cell’s surrounding such as substrate deformations due to traction forces126 and modulations of substrate properties,125 and even multiple cells experiencing cell–cell interactions153 can all be integrated in the modelling approach.

One of the major future challenges is to adapt the phase-field approach to a specific type of cell, such as keratocytes, fibroblasts, neutrophils or even stem cells. The problem is nontrivial, as different types of cells may have different propulsion and adhesion mechanisms, different distributions of actin due to internal regulation, adhesion maturation may lead to complex complings, etc. Beyond the obvious diversity in cell shapes, the traction force distribution highlights the differences in the functioning of the motility machinery for different cells: the most studied cell type, fish keratocytes, have highest traction at the sides, fibroblast cells at the moving front and neutrophils at the rear. The reasons for these different distributions—and their advantages for motility and function—remain elusive. In addition, environmental conditions may lead cells to change their phenotype: e.g., neutrophils exhibit ameboidal motion on strongly adhesive surfaces and more persistent, keratocyte-like behaviour on substrates with moderate density of adhesive ligands.161 Stem cells, in turn, are known to change the phenotype as a function of substrate stiffness.162 Hence, significant and targeted modifications of the existing phase-field algorithms are needed to describe these effects. The most immediate task probably is to introduce a more detailed description of the cell’s contractile elements (like stress fibers and actin arcs) and to improve on the adhesion dynamics, including maturation.163,164

One field of application, where phase-field methods proved to be very powerful, is cell motion on substrates with modulated stiffness and/or adhesiveness. A number of nontrivial cellular responses have been reproduced, including directed motion along adhesive stripes,125 scattering of cells from substrates with step-like modulations of adhesion or stiffness126 and motion along stiffness gradients (durotaxis),126 as well as periodic migration of cells and their turning behaviour on micropatterned substrates.126,131 The phase-field model matched many experimental observations and already led to testable predictions; for instance, a transition from motion along adhesive stripes25 to a transverse motion upon reduction of the overall adhesiveness.125 Phase-field methods are becoming a valuable computational tool for predictive modelling of cell motion on complex heterogeneous substrates. We hence anticipate that they will have an increasing role in the design of biomedical assays for cell sorting, manipulation and analysis, both on structured substrates and in narrow channels or constrictions.38

Equally successful was the phase-field approach applied to multiple migrating cells.151–153 It was able to reproduce many experimentally observed effects, including inelastic scattering of colliding cells and ‘activation’ of nonmotile cells by moving cells owing to steric interactions153 and the emergence of coherently moving or rotating cell clusters,152,153 as well as the formation of tissue-like stationary clusters.151,153 Again, computational modelling produced a number of important insights, e.g., it was shown that—at least in a non-confluent situation—cell–cell adhesion rather hinders collective migration of cells, as it induces the formation of short-living clusters of only few cells.153 This observation sheds light, for instance, on comparative studies of adhesive (healthy) cells versus weakly adhering (cancerous) cells.94

Currently, in all multicell approaches a separate phase field was assigned to each cell,150–153 permitting with the present power of graphic processing units to simulate about a hundred cells. This approach, however, is computationally not yet optimized, as a substantial part of the computing time is spend on updating zeros (note that most fields are typically zero outside the cells). This issue becomes crucial when going to larger ensembles of cells or to three-dimensional situations. In this respect, a phase-field method capable of describing multiple moving cells within a single or few phase fields is highly desirable. In Aland et al.165 and Alaimo et al.,166 a so-called ‘phase-field crystal’ model167,168 was applied to describe cell migration in epithelial colony growth. In this approach, a single mass-conserving phase-field equation is used to describe multiple cells. The method is well suited for the description of a quasistationary colony or tissue or for an almost confluent layer of the cells. However, for rapidly moving cells or cells with nonstationary motility modes such as considered by Löber et al.,153 the approach may produce numerical artefacts such as cell merging or breakup. In this respect, adaptive methods may better be suited: since nothing has to be updated far away from the cells, the mesh size can be increased adaptively to reduce the computational costs169 (see e.g., Ling et al.170 for a recent adaptive multimesh approach for deformable objects). Also, hybrid particle-mesh methods for solving the hydrodynamic equations of incompressible active polar viscous gels can be applied to describe moving deformable objects.171 The efficiency can be possibly increased even further by applying the renormalization group approach to the phase-field method, as performed in a different context by Goldenfeld et al.172 Finally, one could develop an algorithm assigning a single phase field to several well-separated cells. As it is evident, e.g., from Figure 6, each migrating cell has only a few immediate neighbours with whom it interacts. As the phase fields are exponentially localized, and a hexagonal lattice is close to the densest packing, a description with about 10 phase fields should be sufficient to compute arbitrary many cells if neighbour lists are used: when cells within one list come too close to each other, they are transferred to another list to avoid merging and other undesired behaviour. Since such list updates are expected to be relatively rare, one can anticipate significant computational speedup.

The majority of the current models for cell motility are two dimensional, i.e., designed for flattened cells moving on topographically flat substrates. A fully three-dimensional description of cell migration would be obviously highly desirable to capture the motion of cells on substrates with complex topographical features (bumps, ridges, pillars) and is truly needed, for instance, in the context of cancer cell proliferation through a tissue. As a first step, a three-dimensional model for an active gel droplet interacting with a flat substrate was developed by Tjhung et al.159 While the model was able to capture realistically looking shapes of crawling cells, significant modelling efforts are still needed for the description of self-organized cell migration through three-dimensional heterogeneous environments.

Multiple scale approaches are another topic that is currently much under development. One advantage of the phase-field approach is that it is able to describe single cells in much detail, and also is perfectly suited to describe many cells. This makes it a valuable tool to bridge the gap between single cells and cell monolayers or tissues. For instance, the subcritical onset of motion and the bistable behaviour of cells are important aspects of motile cells and may affect the collective cell behaviour on many levels. It is responsible, e.g., for the formation of tissue-like clusters from a dispersion of migrating cells.153 While the onset of motion and bistability are captured by the phase-field approach, these effects are typically not accounted for in simpler models of cell migration, such as CPMs,94 which address a constant propulsion force with a certain persistence time to each cell. Consequently, the phase-field approach is best suited for nonconfluent situations when the motion of individual cells needs to be accurately resolved. For confluent layers, the approach may be too detailed as effects average out, and more coarse-grained methods, such as CPMs,94,95 phase-field crystal models165 or phenomenological and continuum approaches,66,173 may be computationally more efficient. In turn, the mesoscale phase-field approach could establish important connections between single-cell behaviour and coarse-grained or continuum approaches of cell monolayers, aggregates and tissues. We therefore anticipate phase-field methods to become an important component in building multiscale computational tools modelling cellular behaviour.

Last but not least, the concepts developed for cell migration can be used to model several related processes and systems: on the one hand, other biological processes involving actin-based membrane motion, such as cell division or phagocytosis (the engulfment of objects by cells). On the other hand, advances in modelling of motile cells can provide insights into the design of synthetic, biomimetic systems like actively self-healing materials. In that context self-propelled synthetic particle-laden capsules174 or other ‘healing agents’ have been envisioned that are able to ‘sense’ a damage, migrate to the damaged sites and upon arrival rupture and repair the damage, similar as wound healing cells do in tissues. There are already successful experimental realizations of this idea,175 using e.g., chemically powered catalytic gold-platinum rods that detect cracks and repair microscopic defects in electric pathways. We anticipate that computational approaches, transferring the knowledge of substrate-based migrating living cells, can support and stimulate the design of such actively self-healing materials.

References

Abercrombie, M. The crawling movement of metazoan cells. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 207, 129–147 (1980).

Sheetz, M. P., Felsenfeld, D., Galbraith, C. G. & Choquet, D. Cell migration as a five-step cycle. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 65, 233–243 (1999).

Carlier, M. F. & Pantaloni, D. Control of actin assembly dynamics in cell motility. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23005–23009 (2007).

Pollard, T. D. & Cooper, J. A. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. Science 326, 1208 (2009).

Lee, J. & Jacobson, K. The composition and dynamics of cell–substratum adhesions in locomoting fish keratocytes. J. Cell Sci. 110, 2833 (1997).