Abstract

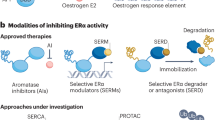

Most breast cancers are driven by oestrogen receptor-α. Anti-oestrogenic drugs are the standard treatment for these breast cancers; however, treatment resistance is common, necessitating new therapeutic strategies. Recent preclinical and historical clinical studies support the use of progestogens to activate the progesterone receptor (PR) in breast cancers. However, widespread controversy exists regarding the role of progestogens in this disease, hindering the clinical implementation of PR-targeted therapies. Herein, we present and discuss data at the root of this controversy and clarify the confusion and misinterpretations that have consequently arisen. We then present our view on how progestogens may be safely and effectively used in treating breast cancer.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

30 November 2016

In this article, the sentence "The T47D-Y derivatives express substantially lower levels of ER than endogenous T47D cells." on page 8 was incorrectly referenced. The correct references are 119 and 135, not 23 and 135. This has been corrected online.

References

Stierer, M. et al. Immunohistochemical and biochemical measurement of estrogen and progesterone receptors in primary breast cancer. Correlation of histopathology and prognostic factors. Ann. Surg. 218, 13–21 (1993).

Germain, P., Staels, B., Dacquet, C., Spedding, M. & Laudet, V. Overview of nomenclature of nuclear receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 58, 685–704 (2006).

Musgrove, E. A. & Sutherland, R. L. Biological determinants of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 631–643 (2009).

Toy, W. et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 45, 1439–1445 (2013).

Robinson, D. R. et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 45, 1446–1451 (2013).

Merenbakh-Lamin, K. et al. D538G mutation in estrogen receptor-α: a novel mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 73, 6856–6864 (2013).

Pannuti, F. et al. Prospective, randomized clinical trial of two different high dosages of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MAP) in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 15, 593–601 (1979).

Alexieva-Figusch, J. et al. Progestin therapy in advanced breast cancer: megestrol acetate — an evaluation of 160 treated cases. Cancer 46, 2369–2372 (1980).

Izuo, M., Iino, Y. & Endo, K. Oral high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate (MAP) in treatment of advanced breast cancer. A preliminary report of clinical and experimental studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1, 125–130 (1981).

Ingle, J. N. et al. Randomized clinical trial of megestrol acetate versus tamoxifen in paramenopausal or castrated women with advanced breast cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 5, 155–160 (1982).

Mattsson, W. Current status of high dose progestin treatment in advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 3, 231–235 (1983).

Morgan, L. R. Megestrol acetate v tamoxifen in advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal patients. Semin. Oncol. 12, 43–47 (1985).

Espie, M. Megestrol acetate in advanced breast carcinoma. Oncology 51 (Suppl. 1), 8–12 (1994).

Birrell, S. N., Roder, D. M., Horsfall, D. J., Bentel, J. M. & Tilley, W. D. Medroxyprogesterone acetate therapy in advanced breast cancer: the predictive value of androgen receptor expression. J. Clin. Oncol. 13, 1572–1577 (1995).

Muss, H. B. et al. Megestrol acetate versus tamoxifen in advanced breast cancer: 5-year analysis — a phase III trial of the Piedmont Oncology Association. J. Clin. Oncol. 6, 1098–1106 (1988).

Robertson, J. F. et al. Factors predicting the response of patients with advanced breast cancer to endocrine (Megace) therapy. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 25, 469–475 (1989).

Abrams, J. et al. Dose−response trial of megestrol acetate in advanced breast cancer: cancer and leukemia group B phase III study 8741. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 64–73 (1999).

Bines, J. et al. Activity of megestrol acetate in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer after nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor failure: a phase II trial. Ann. Oncol. 25, 831–836 (2014).

Beral, V. et al. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 362, 419–427 (2003).

Chlebowski, R. T. et al. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA 289, 3243–3253 (2003).

Rossouw, J. E. et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288, 321–333 (2002).

Wu, J., Richer, J., Horwitz, K. B. & Hyder, S. M. Progestin-dependent induction of vascular endothelial growth factor in human breast cancer cells: preferential regulation by progesterone receptor B. Cancer Res. 64, 2238–2244 (2004).

Liang, Y., Besch-Williford, C., Brekken, R. A. & Hyder, S. M. Progestin-dependent progression of human breast tumor xenografts: a novel model for evaluating antitumor therapeutics. Cancer Res. 67, 9929–9936 (2007).

Faivre, E. J. & Lange, C. A. Progesterone receptors upregulate Wnt-1 to induce epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and c-Src-dependent sustained activation of Erk1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase in breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 466–480 (2007).

Lanari, C. et al. The MPA mouse breast cancer model: evidence for a role of progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 16, 333–350 (2009).

Giulianelli, S. et al. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates progestin-induced mammary tumor growth by interacting with progesterone receptors at the Cyclin D1/MYC promoters. Cancer Res. 72, 2416–2427 (2012).

Tanos, T. et al. Progesterone/RANKL is a major regulatory axis in the human breast. Sci. Transl Med. 5, 182ra155 (2013).

Dressing, G. E. et al. Progesterone receptor−cyclin D1 complexes induce cell cycle-dependent transcriptional programs in breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 28, 442–457 (2014).

Carroll, J. S. & Brown, M. Estrogen receptor target gene: an evolving concept. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1707–1714 (2006).

Kininis, M. & Kraus, W. L. A global view of transcriptional regulation by nuclear receptors: gene expression, factor localization, and DNA sequence analysis. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 6, e005 (2008).

Peters, A. A. et al. Androgen receptor inhibits estrogen receptor-α activity and is prognostic in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 69, 6131–6140 (2009).

Arora, V. K. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor confers resistance to antiandrogens by bypassing androgen receptor blockade. Cell 155, 1309–1322 (2013).

Daniel, A. R. et al. Progesterone receptor-B enhances estrogen responsiveness of breast cancer cells via scaffolding PELP1- and estrogen receptor-containing transcription complexes. Oncogene 34, 506–515 (2015).

Isikbay, M. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor activity contributes to resistance to androgen-targeted therapy in prostate cancer. Horm. Cancer 5, 72–89 (2014).

Mohammed, H. et al. Progesterone receptor modulates ERα action in breast cancer. Nature 523, 313–317 (2015).

Carreau, S. & Levallet, J. Testicular estrogens and male reproduction. News Physiol. Sci. 15, 195–198 (2000).

Oettel, M. & Mukhopadhyay, A. K. Progesterone: the forgotten hormone in men? Aging Male 7, 236–257 (2004).

Graham, J. D. & Clarke, C. L. Physiological action of progesterone in target tissues. Endocr. Rev. 18, 502–519 (1997).

Edwards, D. P. Regulation of signal transduction pathways by estrogen and progesterone. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 335–376 (2005).

Horwitz, K. B. & McGuire, W. L. Estrogen control of progesterone receptor in human breast cancer. Correlation with nuclear processing of estrogen receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 2223–2228 (1978).

Pichon, M. F., Pallud, C., Brunet, M. & Milgrom, E. Relationship of presence of progesterone receptors to prognosis in early breast cancer. Cancer Res. 40, 3357–3360 (1980).

Ballare, C. et al. Two domains of the progesterone receptor interact with the estrogen receptor and are required for progesterone activation of the c-Src/Erk pathway in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1994–2008 (2003).

Muscat, G. E. et al. Research resource: nuclear receptors as transcriptome: discriminant and prognostic value in breast cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 350–365 (2013).

Santagata, S. et al. Taxonomy of breast cancer based on normal cell phenotype predicts outcome. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 859–870 (2014).

Horwitz, K. B. & McGuire, W. L. Predicting response to endocrine therapy in human breast cancer: a hypothesis. Science 189, 726–727 (1975).

Viale, G. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of centrally reviewed expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in a randomized trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal early breast cancer: BIG 1–98. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 3846–3852 (2007).

Stanczyk, F. Z., Hapgood, J. P., Winer, S. & Mishell, D. R. Jr. Progestogens used in postmenopausal hormone therapy: differences in their pharmacological properties, intracellular actions, and clinical effects. Endocr. Rev. 34, 171–208 (2013).

Del Vecchio, R. P. The role of steroidogenic and nonsteroidogenic luteal cell interactions in regulating progesterone production. Semin. Reprod. Endocrinol. 15, 409–420 (1997).

Chaumeil, J. C. Micronization: a method of improving the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 20, 211–215 (1998).

Hargrove, J. T., Maxson, W. S. & Wentz, A. C. Absorption of oral progesterone is influenced by vehicle and particle size. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 161, 948–951 (1989).

Lauritzen, C. Clinical use of oestrogens and progestogens. Maturitas 12, 199–214 (1990).

Apgar, B. S. & Greenberg, G. Using progestins in clinical practice. Am. Fam. Physician 62, 1839–1846 (2000).

Fournier, A., Berrino, F. & Clavel-Chapelon, F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 107, 103–111 (2008).

Chlebowski, R. T. et al. Breast cancer after use of estrogen plus progestin in postmenopausal women. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 573–587 (2009).

Lyytinen, H. K., Dyba, T., Ylikorkala, O. & Pukkala, E. I. A case−control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int. J. Cancer 126, 483–489 (2010).

Manson, J. E. et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 310, 1353–1368 (2013).

Reeves, G. K., Beral, V., Green, J., Gathani, T. & Bull, D. Hormonal therapy for menopause and breast-cancer risk by histological type: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 7, 910–918 (2006).

Dieci, M. V., Orvieto, E., Dominici, M., Conte, P. & Guarneri, V. Rare breast cancer subtypes: histological, molecular, and clinical peculiarities. Oncologist 19, 805–813 (2014).

McCart Reed, A. E., Kutasovic, J. R., Lakhani, S. R. & Simpson, P. T. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: morphology, biomarkers and 'omics. Breast Cancer Res. 17, 12 (2015).

Burger, H. G., MacLennan, A. H., Huang, K. E. & Castelo-Branco, C. Evidence-based assessment of the impact of the WHI on women's health. Climacteric 15, 281–287 (2012).

Schernhammer, E. S. et al. Endogenous sex steroids in premenopausal women and risk of breast cancer: the ORDET cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 15, R46 (2013).

Eliassen, A. H. et al. Endogenous steroid hormone concentrations and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 98, 1406–1415 (2006).

Kaaks, R. et al. Serum sex steroids in premenopausal women and breast cancer risk within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J. Natl Cancer Inst. 97, 755–765 (2005).

Chang, K. J., Lee, T. T., Linares-Cruz, G., Fournier, S. & de Lignieres, B. Influences of percutaneous administration of estradiol and progesterone on human breast epithelial cell cycle in vivo. Fertil. Steril. 63, 785–791 (1995).

Clavel-Chapelon, F. & Dormoy-Mortier, N. A validation study on status and age of natural menopause reported in the E3N cohort. Maturitas 29, 99–103 (1998).

Fournier, A., Berrino, F., Riboli, E., Avenel, V. & Clavel-Chapelon, F. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N−EPIC cohort. Int. J. Cancer 114, 448–454 (2005).

Fournier, A. et al. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor-defined invasive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 1260–1268 (2008).

de Lignieres, B. et al. Combined hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer in a French cohort study of 3,175 women. Climacteric 5, 332–340 (2002).

Espie, M. et al. Breast cancer incidence and hormone replacement therapy: results from the MISSION study, prospective phase. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 23, 391–397 (2007).

Schneider, C., Jick, S. S. & Meier, C. R. Risk of gynecological cancers in users of estradiol/dydrogesterone or other HRT preparations. Climacteric 12, 514–524 (2009).

Cordina-Duverger, E. et al. Risk of breast cancer by type of menopausal hormone therapy: a case−control study among post-menopausal women in France. PLoS ONE 8, e78016 (2013).

Fournier, A. et al. Risk of breast cancer after stopping menopausal hormone therapy in the E3N cohort. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 145, 535–543 (2014).

Lippman, M. E. et al. Indicators of lifetime estrogen exposure: effect on breast cancer incidence and interaction with raloxifene therapy in the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation study participants. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 3111–3116 (2001).

Asi, N. et al. Progesterone versus synthetic progestins and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 5, 121 (2016).

Foidart, J. M., Desreux, J., Pintiaux, A. & Gompel, A. Hormone therapy and breast cancer risk. Climacteric 10 (Suppl. 2), 54–61 (2007).

L'Hermite, M., Simoncini, T., Fuller, S. & Genazzani, A. R. Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review. Maturitas 60, 185–201 (2008).

Gadducci, A., Biglia, N., Cosio, S., Sismondi, P. & Genazzani, A. R. Progestagen component in combined hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women and breast cancer risk: a debated clinical issue. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 25, 807–815 (2009).

Mueck, A. O., Seeger, H. & Buhling, K. J. Use of dydrogesterone in hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas 65 (Suppl. 1), S51–S60 (2009).

Wood, C. E. et al. Effects of estradiol with micronized progesterone or medroxyprogesterone acetate on risk markers for breast cancer in postmenopausal monkeys. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 101, 125–134 (2007).

LaCroix, A. Z. Estrogen with and without progestin: benefits and risks of short-term use. Am. J. Med. 118 (Suppl. 12B), 79–87 (2005).

Bentel, J. M. et al. Androgen receptor agonist activity of the synthetic progestin, medroxyprogesterone acetate, in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 154, 11–20 (1999).

Ouatas, T., Halverson, D. & Steeg, P. S. Dexamethasone and medroxyprogesterone acetate elevate Nm23-H1 metastasis suppressor gene expression in metastatic human breast carcinoma cells: new uses for old compounds. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 3763–3772 (2003).

Birrell, S. N., Butler, L. M., Harris, J. M., Buchanan, G. & Tilley, W. D. Disruption of androgen receptor signaling by synthetic progestins may increase risk of developing breast cancer. FASEB J. 21, 2285–2293 (2007).

Bonomi, P. et al. Primary hormonal therapy of advanced breast cancer with megestrol acetate: predictive value of estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor levels. Semin. Oncol. 12, 48–54 (1985).

Johnson, P. A. et al. Progesterone receptor level as a predictor of response to megestrol acetate in advanced breast cancer: a retrospective study. Cancer Treat. Rep. 67, 717–720 (1983).

Carpenter, J. T. in Endocrine Therapies in Breast and Prostate Cancer (ed. Osborne, C. K.) 147–156 (Kluwer, 1988).

Sutherland, R. L., Hall, R. E., Pang, G. Y., Musgrove, E. A. & Clarke, C. L. Effect of medroxyprogesterone acetate on proliferation and cell cycle kinetics of human mammary carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 48, 5084–5091 (1988).

Poulin, R., Baker, D., Poirier, D. & Labrie, F. Androgen and glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation by medroxyprogesterone acetate in ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 13, 161–172 (1989).

Ory, K. et al. Apoptosis inhibition mediated by medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment of breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 68, 187–198 (2001).

Ochnik, A. M. et al. Antiandrogenic actions of medroxyprogesterone acetate on epithelial cells within normal human breast tissues cultured ex vivo. Menopause 21, 79–88 (2014).

Gizard, F. et al. Progesterone inhibits human breast cancer cell growth through transcriptional upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 gene. FEBS Lett. 579, 5535–5541 (2005).

Kabos, P. et al. Patient-derived luminal breast cancer xenografts retain hormone receptor heterogeneity and help define unique estrogen-dependent gene signatures. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 135, 415–432 (2012).

Vignon, F., Bardon, S., Chalbos, D. & Rochefort, H. Antiestrogenic effect of R5020, a synthetic progestin in human breast cancer cells in culture. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 56, 1124–1130 (1983).

Stingl, J. Estrogen and progesterone in normal mammary gland development and in cancer. Horm. Cancer 2, 85–90 (2011).

Beleut, M. et al. Two distinct mechanisms underlie progesterone-induced proliferation in the mammary gland. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2989–2994 (2010).

Brisken, C. et al. A paracrine role for the epithelial progesterone receptor in mammary gland development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5076–5081 (1998).

Shoker, B. S. et al. Estrogen receptor-positive proliferating cells in the normal and precancerous breast. Am. J. Pathol. 155, 1811–1815 (1999).

Russo, J., Ao, X., Grill, C. & Russo, I. H. Pattern of distribution of cells positive for estrogen receptor α and progesterone receptor in relation to proliferating cells in the mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 53, 217–227 (1999).

De Silva, D., Kunasegaran, K., Ghosh, S. & Pietersen, A. M. Transcriptome analysis of the hormone-sensing cells in mammary epithelial reveals dynamic changes in early pregnancy. BMC Dev. Biol. 15, 7 (2015).

Virgo, B. B. & Bellward, G. D. Serum progesterone levels in the pregnant and postpartum laboratory mouse. Endocrinology 95, 1486–1490 (1974).

Ewan, K. B. et al. Proliferation of estrogen receptor-α-positive mammary epithelial cells is restrained by transforming growth factor-β1 in adult mice. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 409–417 (2005).

Mastroianni, M. et al. Wnt signaling can substitute for estrogen to induce division of ERα-positive cells in a mouse mammary tumor model. Cancer Lett. 289, 23–31 (2010).

Fridriksdottir, A. J. et al. Propagation of oestrogen receptor-positive and oestrogen-responsive normal human breast cells in culture. Nat. Commun. 6, 8786 (2015).

Dontu, G. & Ince, T. A. Of mice and women: a comparative tissue biology perspective of breast stem cells and differentiation. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 20, 51–62 (2015).

Schramek, D., Sigl, V. & Penninger, J. M. RANKL and RANK in sex hormone-induced breast cancer and breast cancer metastasis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22, 188–194 (2011).

Hiremath, M., Lydon, J. P. & Cowin, P. The pattern of β-catenin responsiveness within the mammary gland is regulated by progesterone receptor. Development 134, 3703–3712 (2007).

Graham, J. D. et al. DNA replication licensing and progenitor numbers are increased by progesterone in normal human breast. Endocrinology 150, 3318–3326 (2009).

McManus, M. J. & Welsch, C. W. The effect of estrogen, progesterone, thyroxine, and human placental lactogen on DNA synthesis of human breast ductal epithelium maintained in athymic nude mice. Cancer 54, 1920–1927 (1984).

Laidlaw, I. J. et al. The proliferation of normal human breast tissue implanted into athymic nude mice is stimulated by estrogen but not progesterone. Endocrinology 136, 164–171 (1995).

Foidart, J. M. et al. Estradiol and progesterone regulate the proliferation of human breast epithelial cells. Fertil. Steril. 69, 963–969 (1998).

Hilton, H. N. et al. Acquired convergence of hormone signaling in breast cancer: ER and PR transition from functionally distinct in normal breast to predictors of metastatic disease. Oncotarget 5, 8651–8664 (2014).

De Maeyer, L. et al. Does estrogen receptor negative/progesterone receptor positive breast carcinoma exist? J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 335–336 (2008).

Quong, J. et al. Age-dependent changes in breast cancer hormone receptors and oxidant stress markers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 76, 221–236 (2002).

Azim, H. A. Jr. et al. RANK-ligand (RANKL) expression in young breast cancer patients and during pregnancy. Breast Cancer Res. 17, 24 (2015).

Sanger, N. et al. OPG and PgR show similar cohort specific effects as prognostic factors in ER positive breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 8, 1196–1207 (2014).

Blows, F. M. et al. Subtyping of breast cancer by immunohistochemistry to investigate a relationship between subtype and short and long term survival: a collaborative analysis of data for 10,159 cases from 12 studies. PLoS Med. 7, e1000279 (2010).

Purdie, C. A. et al. Progesterone receptor expression is an independent prognostic variable in early breast cancer: a population-based study. Br. J. Cancer 110, 565–572 (2014).

Welsh, A. W. et al. Cytoplasmic estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 118–126 (2012).

Singhal, H. et al. Genomic agonism and phenotypic antagonism between estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501924 (2016).

Zheng, Z. Y., Bay, B. H., Aw, S. E. & Lin, V. C. A novel antiestrogenic mechanism in progesterone receptor-transfected breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17480–17487 (2005).

Swarbrick, A., Lee, C. S., Sutherland, R. L. & Musgrove, E. A. Cooperation of p27Kip1 and p18INK4c in progestin-mediated cell cycle arrest in T-47D breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2581–2591 (2000).

Musgrove, E. A., Swarbrick, A., Lee, C. S., Cornish, A. L. & Sutherland, R. L. Mechanisms of cyclin-dependent kinase inactivation by progestins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 1812–1825 (1998).

Prall, O. W., Sarcevic, B., Musgrove, E. A., Watts, C. K. & Sutherland, R. L. Estrogen-induced activation of Cdk4 and Cdk2 during G1−S phase progression is accompanied by increased cyclin D1 expression and decreased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor association with cyclin E−Cdk2. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 10882–10894 (1997).

Hagan, C. R., Daniel, A. R., Dressing, G. E. & Lange, C. A. Role of phosphorylation in progesterone receptor signaling and specificity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 357, 43–49 (2012).

Hagan, C. R. & Lange, C. A. Molecular determinants of context-dependent progesterone receptor action in breast cancer. BMC Med. 12, 32 (2014).

Musgrove, E. A., Lee, C. S. & Sutherland, R. L. Progestins both stimulate and inhibit breast cancer cell cycle progression while increasing expression of transforming growth factor α, epidermal growth factor receptor, c-fos, and c-myc genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 5032–5043 (1991).

Groshong, S. D. et al. Biphasic regulation of breast cancer cell growth by progesterone: role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, 21 and p27Kip1. Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 1593–1607 (1997).

Chalbos, D. & Rochefort, H. Dual effects of the progestin R5020 on proteins released by the T47D human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 1231–1238 (1984).

Hissom, J. R. & Moore, M. R. Progestin effects on growth in the human breast cancer cell line T-47D — possible therapeutic implications. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 145, 706–711 (1987).

Graham, J. D. et al. Progesterone receptor A and B protein expression in human breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 56, 93–98 (1996).

Graham, J. D. et al. Altered progesterone receptor isoform expression remodels progestin responsiveness of breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 2713–2735 (2005).

Sartorius, C. A. et al. New T47D breast cancer cell lines for the independent study of progesterone B− and A− receptors: only antiprogestin-occupied B-receptors are switched to transcriptional agonists by cAMP. Cancer Res. 54, 3868–3877 (1994).

Graham, M. L. 2nd et al. T47DCO cells, genetically unstable and containing estrogen receptor mutations, are a model for the progression of breast cancers to hormone resistance. Cancer Res. 50, 6208–6217 (1990).

Berkenstam, A., Glaumann, H., Martin, M., Gustafsson, J. A. & Norstedt, G. Hormonal regulation of estrogen receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in T47Dco and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 3, 22–28 (1989).

Harvell, D. M., Richer, J. K., Allred, D. C., Sartorius, C. A. & Horwitz, K. B. Estradiol regulates different genes in human breast tumor xenografts compared with the identical cells in culture. Endocrinology 147, 700–713 (2006).

Sartorius, C. A., Shen, T. & Horwitz, K. B. Progesterone receptors A and B differentially affect the growth of estrogen-dependent human breast tumor xenografts. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 79, 287–299 (2003).

Nadji, M., Gomez-Fernandez, C., Ganjei-Azar, P. & Morales, A. R. Immunohistochemistry of estrogen and progesterone receptors reconsidered: experience with 5,993 breast cancers. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 123, 21–27 (2005).

Hefti, M. M. et al. Estrogen receptor negative/progesterone receptor positive breast cancer is not a reproducible subtype. Breast Cancer Res. 15, R68 (2013).

Cerliani, J. P. et al. Interaction between FGFR-2, STAT5, and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 71, 3720–3731 (2011).

Howlader, N. et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2009 National Cancer Institute http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2009_pops09/results_merged/sect_04_breast.pdf (2006).

Howell, A. et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet 365, 60–62 (2005).

BIG 1–98 Collaborative Group. Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 766–776 (2009).

Melmon, K. L., Morrelli, H. F. & Carruthers, S. G. Melmon and Morrelli's Clinical Pharmacology: Basic Principles in Therapeutics (McGraw Hill Professional, 2000).

Bardou, V. J., Arpino, G., Elledge, R. M., Osborne, C. K. & Clark, G. M. Progesterone receptor status significantly improves outcome prediction over estrogen receptor status alone for adjuvant endocrine therapy in two large breast cancer databases. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 1973–1979 (2003).

Stendahl, M. et al. High progesterone receptor expression correlates to the effect of adjuvant tamoxifen in premenopausal breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 4614–4618 (2006).

Jonat, W. et al. A randomised trial comparing two doses of the new selective aromatase inhibitor anastrozole (Arimidex) with megestrol acetate in postmenopausal patients with advanced breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 32A, 404–412 (1996).

Buzdar, A. U. et al. A phase III trial comparing anastrozole (1 and 10 milligrams), a potent and selective aromatase inhibitor, with megestrol acetate in postmenopausal women with advanced breast carcinoma. Arimidex Study Group. Cancer 79, 730–739 (1997).

Buzdar, A. et al. Phase III, multicenter, double-blind, randomized study of letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, for advanced breast cancer versus megestrol acetate. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 3357–3366 (2001).

Partridge, A. H., Wang, P. S., Winer, E. P. & Avorn, J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 602–606 (2003).

Kligman, L. & Younus, J. Management of hot flashes in women with breast cancer. Curr. Oncol. 17, 81–86 (2010).

Makubate, B., Donnan, P. T., Dewar, J. A., Thompson, A. M. & McCowan, C. Cohort study of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy, breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Br. J. Cancer 108, 1515–1524 (2013).

Loprinzi, C. L. et al. Megestrol acetate for the prevention of hot flashes. N. Engl. J. Med. 331, 347–352 (1994).

Hickey, T. E., Robinson, J. L., Carroll, J. S. & Tilley, W. D. Minireview: the androgen receptor in breast tissues: growth inhibitor, tumor suppressor, oncogene? Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 1252–1267 (2012).

Hua, S., Kittler, R. & White, K. P. Genomic antagonism between retinoic acid and estrogen signaling in breast cancer. Cell 137, 1259–1271 (2009).

Ross-Innes, C. S. et al. Cooperative interaction between retinoic acid receptor-α and estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Genes Dev. 24, 171–182 (2010).

Darro, F. et al. Growth inhibition of human in vitro and mouse in vitro and in vivo mammary tumor models by retinoids in comparison with tamoxifen and the RU-486 anti-progestagen. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 51, 39–55 (1998).

Vilasco, M. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 130, 1–10 (2011).

Miranda, T. B. et al. Reprogramming the chromatin landscape: interplay of the estrogen and glucocorticoid receptors at the genomic level. Cancer Res. 73, 5130–5139 (2013).

De Amicis, F. et al. Androgen receptor overexpression induces tamoxifen resistance in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 121, 1–11 (2010).

Rechoum, Y. et al. AR collaborates with ERα in aromatase inhibitor-resistant breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 147, 473–485 (2014).

Bardon, S., Vignon, F., Chalbos, D. & Rochefort, H. RU486, a progestin and glucocorticoid antagonist, inhibits the growth of breast cancer cells via the progesterone receptor. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 60, 692–697 (1985).

Horwitz, K. B. The antiprogestin RU38 486: receptor-mediated progestin versus antiprogestin actions screened in estrogen-insensitive T47Dco human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 116, 2236–2245 (1985).

Musgrove, E. A., Lee, C. S., Cornish, A. L., Swarbrick, A. & Sutherland, R. L. Antiprogestin inhibition of cell cycle progression in T-47D breast cancer cells is accompanied by induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 54–66 (1997).

Klijn, J. G., Setyono-Han, B. & Foekens, J. A. Progesterone antagonists and progesterone receptor modulators in the treatment of breast cancer. Steroids 65, 825–830 (2000).

Bakker, G. H. et al. Comparison of the actions of the antiprogestin mifepristone (RU486), the progestin megestrol acetate, the LHRH analog buserelin, and ovariectomy in treatment of rat mammary tumors. Cancer Treat. Rep. 71, 1021–1027 (1987).

Michna, H., Schneider, M. R., Nishino, Y. & el Etreby, M. F. Antitumor activity of the antiprogestins ZK 98.299 and RU 38.486 in hormone dependent rat and mouse mammary tumors: mechanistic studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 14, 275–288 (1989).

Bakker, G. H. et al. Treatment of breast cancer with different antiprogestins: preclinical and clinical studies. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 789–794 (1990).

Iwasaki, K. et al. Effects of antiprogestins on the rate of proliferation of breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 198, 141–149 (1999).

Perrault, D. et al. Phase II study of the progesterone antagonist mifepristone in patients with untreated metastatic breast carcinoma: a National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group study. J. Clin. Oncol. 14, 2709–2712 (1996).

Jonat, W. et al. Randomized phase II study of lonaprisan as second-line therapy for progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 24, 2543–2548 (2013).

Robertson, J. F., Willsher, P. C., Winterbottom, L., Blamey, R. W. & Thorpe, S. Onapristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, as first-line therapy in primary breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 35, 214–218 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK and Hutchison Whampoa Limited. J.S.C is supported by a European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator grant and a Komen Scholar Award. The work of the authors is supported by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (ID 1008349 to W.D.T. and T.E.H.; ID 1084416 to W.D.T., T.E.H. and J.S.C.); Cancer Australia/National Breast Cancer Foundation of Australia (ID 1043497 to W.D.T., T.E.H. and J.S.C.; ID 1107170 to W.D.T., T.E.H. and J.S.C.); the National Breast Cancer Foundation of Australia (PS-15-041 to W D.T. and G.A.T.); and an unrestricted grant from GTx (W.D.T. and T.E.H.). T.E.H held a Fellowship Award from the US Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (BCRP; #W81XWH-11-1-0592) and currently is supported by a Florey Career Development Fellowship from the Royal Adelaide Hospital Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Michael Williams has represented women with legal claims for breast cancer induced by medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethindrone acetate when used as menopausal hormone therapy. The other authors declare no potential competing interests.

Glossary

- Aromatase inhibitor

-

A class of drugs that inhibit the enzyme aromatase (CYP19A1), which converts androgens (testosterone or androstenedione) into oestrogens. By blocking oestrogen synthesis, these compounds inhibit the action of the oestrogen receptor.

- Basal cells

-

Contractile myoepithelial cells that line mammary ducts and possess a reservoir of stem and progenitor cells. Basal cells are thought to function in milk transport at lactation.

- ER

-

In this article, ER specifically refers to oestrogen receptor-α (ERα) There is also an ERβ, which arises from a different gene, but there is considerable controversy regarding the expression and biological role of ERβ in breast cancer. Most of the literature that refers to ER in breast cancer refers to ERα.

- Hormone replacement therapy

-

This therapy (now called menopausal hormone therapy) is used to ameliorate symptoms that arise as a consequence of menopause in which the ovaries are unable to produce sufficient oestrogen and progesterone hormones.

- Luminal cells

-

Secretory cells that reside juxtaposed to basal cells and are composed of two distinct subpopulations: milk-producing alveolar cells and oestrogen receptor (ER)+ and/or progesterone receptor (PR)+ cells. ER+ and PR+ cells respond to endocrine reproductive cues (for example, oestrogen and progesterone) and translate them into paracrine factors that coordinate mammary development during pregnancy.

- Micronization

-

A process by which large particles are broken down into very small particles to increase surface area. In pharmacology, this process can increase the rate of intestinal absorption of oral drugs. Progesterone is one example of a drug that is not well absorbed unless micronized.

- Microstructures

-

A collection of cells that retain anatomical structure that accurately reflects their site of origin.

- PR-A and PR-B

-

The progesterone receptor (PR) exists in two isoforms, PR-A and PR-B, that are produced from the same gene. PR-B has the same protein sequence as PR-A, but with an additional region termed the 'activation function 3′ at the amino terminus of the protein.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carroll, J., Hickey, T., Tarulli, G. et al. Deciphering the divergent roles of progestogens in breast cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 17, 54–64 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2016.116

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2016.116

This article is cited by

-

Molecular characterization of breast cancer cell pools with normal or reduced ability to respond to progesterone: a study based on RNA-seq

Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (2023)

-

Addition of progesterone to feminizing gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender individuals for breast development: a randomized controlled trial

BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology (2023)

-

Therapeutic resistance to anti-oestrogen therapy in breast cancer

Nature Reviews Cancer (2023)

-

Estrogen receptor positive breast cancers have patient specific hormone sensitivities and rely on progesterone receptor

Nature Communications (2022)

-

A review of prognostic and predictive biomarkers in breast cancer

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2022)