Abstract

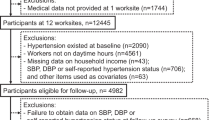

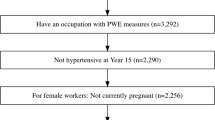

Population-based strategies targeting modifiable risk factors are needed to improve the prevention of hypertension. Long working hours have been linked to high blood pressure (BP), but more longitudinal research is required. The objective of this study was to examine the effect of long working hours (≥41 h/week) on ambulatory BP mean over a 2.5-year follow-up. The effect modification of family responsibilities was also investigated. A repeated longitudinal design was used. Data collection was performed at three-time points over a 2.5-year follow-up among over 2000 white-collar workers. Working hours were self-reported assessed by questionnaire. BP was measured using Spacelabs 90207. The outcomes were systolic and diastolic BP mean. Cross-lagged GEE linear regressions were used to examine whether working hours were associated with BP means at the next measurement time. Women working long hours had a higher diastolic BP mean at follow-up compared to women working regular hours (+1.8 mm Hg (95% CI: 0.5–3.1)). In men, those working long hours had both higher systolic and diastolic BP means increases (systolic: +2.5 mm Hg (95% CI: 0.5–4.4)) and diastolic: +2.3 mm Hg (95% CI: 1.0–3.7)). This association was greater among workers having high family responsibilities. This longitudinal study showed that women and men working long hours had higher BP means when compared those working 35–40 h per week. These findings suggest that strategies that promote work weeks not exceeding 40 h might contribute to the primary prevention of hypertension, especially for workers with high family responsibilities.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

WHO. Cardiovascular diseases. Fact sheet. Media Center, 2011. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/index.html.

GBD. Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–724.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood Pressure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;71:e127–e248.

Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13.

Ke DS. Overwork, stroke, and karoshi-death from overwork. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2012;21:54–9.

Virtanen M, Kivimaki M. Long working hours and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20:123.

Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Singh-Manoux A, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet 2015;386:1739–46.

Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Batty GD, Vahtera J, et al. Long working hours and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:586–96.

Munakata M. Clinical significance of stress-related increase in blood pressure: current evidence in office and out-of-office settings. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:553–69.

Dembe AE, Yao X. Chronic disease risks from exposure to long-hour work schedules over a 32-year period. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:861–7.

Itani O, Kaneita Y, Ikeda M, Kondo S, Murata A, Ohida T. Associations of work hours and actual availability of weekly rest days with cardiovascular risk factors. J Occup Health. 2013;55:11–20.

Nakamura K, Sakurai M, Morikawa Y, Miura K, Ishizaki M, Kido T, et al. Overtime work and blood pressure in normotensive Japanese male workers. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:979–85.

Nakanishi N, Yoshida H, Nagano K, Kawashimo H, Nakamura K, Tatara K. Long working hours and risk for hypertension in Japanese male white collar workers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:316–22.

Pimenta AM, Beunza JJ, Bes-Rastrollo M, Alonso A, Lopez CN, Velasquez-Melendez G, et al. Work hours and incidence of hypertension among Spanish university graduates: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra prospective cohort. J Hypertens. 2009;27:34–40.

Yoo DH, Kang MY, Paek D, Min B, Cho SI. Effect of long working hours on self-reported hypertension among middle-aged and older wage Workers. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2014;26:25.

Wada K, Katoh N, Aratake Y, Furukawa Y, Hayashi T, Satoh E, et al. Effects of overtime work on blood pressure and body mass index in Japanese male workers. Occup Med. 2006;56:578–80.

Boggia J, Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Bjorklund-Bodegard K, et al. Prognostic accuracy of day versus night ambulatory blood pressure: a cohort study. Lancet 2007;370:1219–29.

Liu JE, Roman MJ, Pini R, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG, Devereux RB. Cardiac and arterial target organ damage in adults with elevated ambulatory and normal office blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:564–72.

Schiebinger L. Scientific research must take gender into account. Nature 2014;507:9.

Wilkins R, Wooden M. Two decades of change: the australian labour market 1993–2013. Aust Econ Rev. 2014;47:417–31.

Equality EIfG. Gender equality index 2015: measuring gender equality in the European Union 2005–2012. Publications Office of the European Union. 2015.

Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Pickering TG, Warren K, Schwartz JE. Life-course exposure to job strain and ambulatory blood pressure in men. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:998–1006.

O’Brien E, Coats A, Owens P, Petrie J, Padfield PL, Littler WA, et al. Use and interpretation of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: recommendations of the British Hypertension Society. Br Med J. 2000;320:1128–34.

Cloutier L, Daskalopoulou SS, Padwal R, Lamarre-Cliche M, Bolli P, McLean D, et al. A new algorithm for the diagnosis of hypertension in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:620–30.

Roozedaal WL, Hoekstra RF. Working hours and overtime: balancing economic interests and fundamental rights in a globalized economy. The International Labour and Employment Relations Association (ILERA), editor. 2015; https://www.ilera2015.com/dynamic/full/IL186.pdf.

Santé Québec, Daveluy, C., Chénard, L. Levasseur, M. et Émond A. (sous la direction de) Et votre coeur, ça va? Rapport de l'enquête québécois sur la santé cardiovasculaire 1990, Montréal, Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec, Gouvernement du Québec, 1994.

Brisson C, Blanchette C, Guimont C, Dion G, Moisan J, Vézina M. Reliability and validity of the French version of the 18-item Karasek Job Content Questionnaire. Work Stress 1998;12:322–36.

Larocque B, Brisson C, Blanchette C. Cohérence interne, validité factorielle et validité discriminante de la traduction française des échelles de demande psychologique et de latitude décisionnelle du “Job Content Questionnaire” de Karasek. Rev Epidém et Sté Publ. 1998;46:371–81.

Santé Québec. Enquête québécoise sur la santé cardiovasculaire [Quebec survey on cardiovascular health] 1990, Rapport final. 1993.

Niedhammer I, Siegrist J, Landre MF, Goldberg M, Leclerc A. Étude des qualités psychométriques de la version française du modèle du Déséquilibre Efforts/Récompenses. Rev Epidém et Sté Publ. 2000;48:419–37.

Brisson C, Laflamme N, Moisan J, Milot A, Mâsse B, Vézina M. Effect of family responsibilities and job strain on ambulatory blood pressure among white-collar women. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:205–13.

Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20:488–95.

Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:267–78.

WHO. Global NCD target. Reduce high blood pressure. World Health Organization; 2015.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Last TL. Modern epidemiology. 3rd ed. Wolters Kluwer | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Gilbert-Ouimet M, Trudel X, Brisson C, Milot A, Vezina M. Adverse effects of psychosocial work factors on blood pressure: systematic review of studies on demand-control-support and effort-reward imbalance models. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;40:109–32.

Li J, Pega F, Ujita Y, Brisson C, Clays E, Descatha A, et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int. 2020;142:105739.

Oh JI, Yim HW. Association between rotating night shift work and metabolic syndrome in Korean workers: differences between 8-hour and 12-hour rotating shift work. Ind Health. 2018;56:40–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants and organisations that participated in this study. We would also like the thank Caty Blanchette, biostatistician, for performing the analyses and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of a CIHR funded research project lead by CB on work stressors and cardiovascular health; MGO is chairholder of the Canada Research Chair in sex and gender in occupational health when the work was conducted; DT is a FRQ-S chercheur-boursier.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gilbert-Ouimet, M., Trudel, X., Talbot, D. et al. Long working hours associated with elevated ambulatory blood pressure among female and male white-collar workers over a 2.5-year follow-up. J Hum Hypertens 36, 207–217 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-021-00499-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-021-00499-3

This article is cited by

-

Longitudinal plasmode algorithms to evaluate statistical methods in realistic scenarios: an illustration applied to occupational epidemiology

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2023)

-

Self-Employment, Working Hours, and Hypertension by Race/Ethnicity in the USA

Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023)