Abstract

It has been difficult to find robust brain structural correlates of the overall severity of major depressive disorder (MDD). We hypothesized that specific symptoms may better reveal correlates and investigated this for the severity of insomnia, both a key symptom and a modifiable major risk factor of MDD. Cortical thickness, surface area and subcortical volumes were assessed from T1-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 1053 MDD patients (age range 13-79 years) from 15 cohorts within the ENIGMA MDD Working Group. Insomnia severity was measured by summing the insomnia items of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). Symptom specificity was evaluated with correlates of overall depression severity. Disease specificity was evaluated in two independent samples comprising 2108 healthy controls, and in 260 clinical controls with bipolar disorder. Results showed that MDD patients with more severe insomnia had a smaller cortical surface area, mostly driven by the right insula, left inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis, left frontal pole, right superior parietal cortex, right medial orbitofrontal cortex, and right supramarginal gyrus. Associations were specific for insomnia severity, and were not found for overall depression severity. Associations were also specific to MDD; healthy controls and clinical controls showed differential insomnia severity association profiles. The findings indicate that MDD patients with more severe insomnia show smaller surfaces in several frontoparietal cortical areas. While explained variance remains small, symptom-specific associations could bring us closer to clues on underlying biological phenomena of MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple findings highlight the importance of insomnia for psychiatric disorders in general, and in particular for major depressive disorder (MDD)1. Insomnia is a primary risk factor for developing MDD, e.g., ref. 2, and its presence in people suffering from MDD hampers the effectiveness of clinical interventions, e.g., ref. 3. Treating insomnia can also improve the outcome of patients suffering from depression4,5. Moreover, recent genome-wide association studies report a strong genetic correlation between insomnia and depressive symptoms and MDD6,7. Given these findings, it seems highly relevant to identify neural correlates of insomnia severity in people suffering from MDD.

To date, brain structural correlates of insomnia symptoms in people with MDD are largely unexplored. Elucidating such correlates may provide key clues to ultimately uncovering the neural correlates of the risk for MDD development. Several anatomical magnetic resonance imaging studies compared people with insomnia disorder (ID) without MDD to those without sleep complaints. People with ID reported smaller gray matter (GM) volumes in the orbitofrontal (OFC)8,9,10, parietal8 as well as middle cingulate11 cortices, the pineal gland12, the thalamus13, and a smaller volume and surface area in the inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis14, as well as a larger GM volume in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC)9. Some studies have suggested a smaller hippocampal volume in people with insomnia15,16, but these findings could not be replicated, e.g., refs. 8,9,10,17. Other studies in people with ID assessed cortical thickness and found a thinner cortex in the ACC, precentral and lateral prefrontal cortex18 and a thicker cortex in several OFC regions, the rACC, middle cingulate cortex, insula, superior parietal cortex, and fusiform area19. In MDD patients, brain structural correlates of insomnia severity have hardly been investigated. A larger amygdala and smaller medial OFC have been reported in MDD patients with insomnia20,21 as compared to MDD patients without insomnia.

It is tempting to presume that brain areas involved in the severity of insomnia in people without MDD are also involved in the severity of insomnia in people suffering from MDD. However, the complexity of the neuronal networks involved in sleep regulation and MDD makes it also conceivable that different brain mechanisms can underlie seemingly similar sleep complaints22,23. The present study therefore applied a whole-brain analysis to uncover brain structural correlates of insomnia severity in people diagnosed with MDD. We evaluated, in a sample of 1053 MDD patients, whether insomnia severity was associated with global and regional differences in cortical thickness, cortical surface areas, and volumes of subcortical regions. Additionally, we evaluated whether the identified associations: (1) were specific to insomnia or driven by overall depression severity and (2) specific to MDD or also present in healthy controls (n = 2108) and clinical controls with bipolar disorder (BD; n = 260).

Materials and methods

Samples

Data for the main analysis were assembled from 15 independent samples of the ENIGMA (Enhancing NeuroImaging Genetics through Mega-Analysis) MDD working group (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/). We included 1053 people who met criteria for current MDD and had completed the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)24. Supplementary Table S1 lists the diagnostic instruments and the exclusion criteria applied at each of the 15 participating sites. Additional data from clinical controls and healthy controls were assembled to evaluate whether insomnia associations were specific to MDD (see Supplementary Methods for details). For clinical controls, we were able to include 260 patients from 5 ENIGMA BD working group sites in whom the HDRS had been assessed (see Supplementary Table S2 for demographics). Next to a first healthy control sample of ENIGMA (n = 1277 completed the HDRS), we evaluated associations in a second healthy control sample from the Human Connectome Project (HCP)25 of which n = 831 had completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)26 (see Supplementary Table S3 for demographics). Exclusion criteria for healthy controls were a history of MDD, a current diagnosis of MDD, or any other psychiatric disorders. All sites obtained approval from local institutional review boards and ethics committees. All participants provided informed consent.

Severity of insomnia and overall depression severity

Three HDRS items were summed to obtain a valid insomnia severity score27 and the remaining items for an insomnia-independent depression severity score, here referred to as the HDRS-14 (Supplementary Methods). In the second healthy control sample (HCP), corresponding PSQI items were summed to obtain an insomnia severity score and an insomnia-independent depression severity score was calculated by excluding the sleep item from the total depression score of the Achenbach Adult Self Report questionnaire28. Supplementary Methods provide details and validation.

Image processing and analysis

Image acquisition parameters for each site are provided in Supplementary Table S4. Schmaal et al. and Glasser et al.29,30,31 provide details of the use of FreeSurfer32 segmentation to obtain surface area and thickness of 68 cortical regions33, as well as 14 subcortical volumes, lateral ventricle volumes, 2 whole-hemisphere measures, and intracranial volume (ICV).

Statistical analyses

MDD patients

Linear mixed-effects models regressed insomnia severity on surface and thickness of cortical regions and subcortical volume. First, we evaluated whether insomnia severity could be predicted from the overall cortical surface area, its average thickness, or from total subcortical volume. Separate models subsequently evaluated individual brain regions. Models were adjusted for age, sex, scanner site (random intercept), insomnia-independent depression severity, and, for subcortical volumes, total ICV. False discovery rate (FDR)34 correction (p < 0.05) was applied to correct the p values for multiple comparisons for cortical surface areas and thickness, and subcortical volumes (respectively, 68, 68, and 16 comparisons).

Specificity of detected associations for insomnia versus overall depressive symptoms severity was assessed with corresponding models with either overall HDRS-17 depression severity or the HDRS-14 insomnia-independent depression severity as outcome.

Ancillary mixed-effects models including interaction terms (e.g., surface area * age, surface area * sex, surface area * antidepressant use, surface area * depression recurrence, surface area * age of onset of depression) investigated whether the association of insomnia severity with cortical surface area, thickness, or subcortical volume was modified or confounded by age, sex, the use of antidepressant medication, depression recurrence (first versus recurrent episode patients), or age of onset of depression.

To obtain effect size measures for single regressors within multivariable mixed-effects models, we calculated Cohen’s f2 statistic. Values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively, indicate a small, medium, or large effect.

The proportion of variance in insomnia severity uniquely explained by the significant brain regions (∆R2) above and beyond the covariates (age, sex, HDRS-14, site, and ICV for subcortical areas) was computed by subtracting the explained variance of a model with only the covariates from the explained variance of the full model (brain area, age, sex, HDRS-14, site, and ICV for subcortical areas) using the MuMln package in R (www.R-project.org).

Clinical controls and healthy controls

Within each of the control samples (BD clinical controls and healthy controls), mixed-effects analyses were repeated, including the same covariates and FDR correction. To formally evaluate whether the insomnia-related brain associations found in MDD were similar or different compared to each of the control samples, models including an interaction term were additionally performed, e.g., surface area * disorder (MDD versus BD). Interaction analyses may lack power and require a larger sample size35. Therefore, it was additionally evaluated whether adding controls to the ENIGMA MDD sample would alter the effect sizes we found in MDD patients. An increase in effect size would support a similar or even stronger association in controls as found in MDD. A decrease in effect size on the contrary would suggest that controls only add noise or have an opposite association.

Results

MDD patients

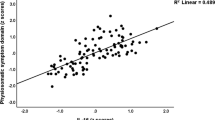

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the MDD patients included at each site separately and overall. Linear mixed-effects regression indicated more severe insomnia in cases with a smaller total cortical surface area (f2 = 0.01, ∆R2 = 0.9%, p = 0.044). Table 2, Fig. 1, and Supplementary Fig. S1 provide the results from subsequent mixed-effects regression analyses to investigate which cortical parcels contributed most to this inverse association. In brief, MDD patients with more severe insomnia had smaller surface areas of the right insula (f2 = 0.02, ∆R2 = 1.5%, pcorrected = 0.031), left inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis (f2 = 0.02, ∆R2 = 1.8%, pcorrected = 0.018), the left frontal pole (f2 = 0.01, ∆R2 = 0.6%, pcorrected = 0.031), right superior parietal cortex (f2 = 0.02, ∆R2 = 1.6%, pcorrected = 0.026), right medial OFC (f2 = 0.02, ∆R2 = 1.3%, pcorrected = 0.031), and the right supramarginal gyrus (f2 = 0.02, ∆R2 = 1.3%, pcorrected = 0.031) (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Together, these brain regions explained 2.7% of the variance in insomnia, above and beyond the variance explained by the covariates. Models including additional covariates (antidepressant medication, depression recurrence, age of onset of depression) did not change the association between surface area and insomnia severity (see Supplementary Results). Ancillary analyses showed that the association between surface area and insomnia severity was not modified or confounded by sex, use of antidepressant medication, depression recurrence, or age of onset of depression. A significant interaction was found between total surface area and age (p = 0.046) (see Supplementary Results). The surface area regions we found explain more variance in insomnia severity than they explain variance in overall depression severity (see Supplemental Results and Supplementary Table S5).

Insomnia severity was not associated with average (p = 0.174) or regional cortical thickness (all pcorrected > 0.574), nor with total (p = 0.595) or local subcortical volume (all pcorrected > 0.886; see Supplementary Tables S6 and S7).

Linear mixed-effects regression models with overall depression severity (HDRS-17) or adjusted depression severity (HDRS-14) as outcome measures revealed no significant predictive value of total (all p > 0.300) or regional surface area (all pcorrected > 0.608), nor for overall average (all p > 0.568) or local cortical thickness (all pcorrected > 0.810), or total (p > 0.354) or local subcortical volume (all pcorrected > 0.238).

Clinical controls and healthy controls

In BD clinical controls, insomnia severity was not significantly associated with any of the six surface areas found in MDD (all f2 < 0.01, p > 0.205), neither with any of the other local surface area, thickness, or subcortical volume measures (all pcorrected > 0.984). To formally evaluate whether the association between insomnia severity and surface areas differed between MDD and BD patients, interaction analyses were performed for each of the six surface areas found in MDD and type of disorder (MDD versus BD). A significant interaction effect was found in only 2 out of the 6 surface areas (left inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis, p = 0.022; right supramarginal gyrus, p = 0.045), indicating that a smaller surface in these two areas was associated with higher insomnia severity specifically in MDD patients but not in BD patients. When combining the BD and MDD sample (n = 1313), the effect sizes decreased by 29–71% as compared to the effects found for cortical surface area in MDD only.

In the ENIGMA-MDD healthy controls, insomnia severity was not significantly associated with any of the six surface areas found in MDD (all f2 < 0.01, p > 0.193), neither with any of the other global or local surface area, thickness, or subcortical volume measures (all pcorrected > 0.441). When adding the ENIGMA healthy controls to the MDD sample (n = 2330), the effect sizes decreased by 34–64% with respect to the significant effects found for cortical surface area in MDD only. In the HCP healthy controls, insomnia severity was only significantly associated with 1 out of the 6 surface areas found in MDD (right medial OFC, f2 = 0.008, p = 0.009; other regions f2 < 0.002, p > 0.188). No significant association was found for any of the other local surface areas or for subcortical volumes (all pcorrected > 0.089), whereas a significant association was found for 2 out of 68 cortical thickness regions. Healthy controls with more severe insomnia showed a thicker right rACC (pcorrected = 0.042) and a thinner right entorhinal cortex (pcorrected = 0.042). Although none of six surface area by group interaction effects reached significance (p > 0.074), interaction effects for the two identified cortical thickness regions did (all p < 0.016), supporting specificity for these regions to healthy controls but not for MDD patients.

Together these results suggest differential association profiles of cortical measures in MDD that in general do not generalize to BD clinical controls or healthy controls.

Discussion

This large-scale study investigated brain structural correlates of insomnia severity in MDD and revealed more severe insomnia in cases with a smaller total surface area. This inverse association with total surface area was mostly driven by the right insula, left inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis, left frontal pole, right superior parietal cortex, right medial OFC, and right supramarginal gyrus, that all showed significant regional effects. The association was independent of depression severity adjusted for the three insomnia items, and was specific for surface area: no associations were found for cortical thickness or subcortical volumes. The association between surface area and insomnia severity seems specific to MDD patients, since no associations were found in healthy or clinical controls. Cortical surface area only explained a small proportion of the variance in insomnia severity, which may not be surprising, because it is conceivable that a variety of other factors influence the complex trait of insomnia. On the other hand, small effects in large samples are more likely to be reliable and reproducible than large effect in small samples36.

We found that surface area was specifically associated with insomnia severity, not with overall depression severity. Our meta-analysis29 in a large overlapping sample of adult MDD patients and controls from ENIGMA MDD reported no significant association between cortical surface area and depression severity measured using the total score of the HDRS. A weak negative association was only found between self-reported depression severity (Beck’s Depression Inventory, BDI-II score) and surface areas of the bilateral precuneus, left frontal pole, and left postcentral gyrus. Our current findings indicate a better association of total and regional surface areas for the severity of a single-domain phenotype (insomnia symptoms) than for the severity of a multi-domain phenotype (all/other mixed symptoms of depression). It should be noted that the explained variance is still small, as is commonly found across genetic and neuroimaging regressors for complex traits like insomnia and depression. While the findings thus do not explain much of individual differences, they may bring us a bit closer to clues on underlying biological phenomena involved.

The Research Domain Criteria approach to psychiatric disease stresses the importance of identifying fundamental symptom dimensions tied to neural systems that cut across heterogeneous mental disorder classifications37. Our findings are the first to identify brain structural correlates related to insomnia, an important clinical symptom of the Arousal and Regulatory Systems domain38, in people suffering from MDD. Notably however, these correlates do not seem to cut across disorders.

Our findings indicate that only cortical surface area is predictive of insomnia severity in MDD, whereas cortical thickness and subcortical volume had no predictive value. Prior studies have shown that these measures represent distinct biological processes. For example, cortical surface area, cortical thickness, and GM volume differ in terms of developmental trajectory39, network topology40, and genetic influences41. As compared to cortical thickness, surface area is more strongly determined by genetic influences42. To identify common genetic variants that underlie these genetic influences on brain structures is not straightforward, as their effects are very small. To overcome this difficulty, >50 ENIGMA sites recently generated a very large sample (n = 35,660) to uncover genetic loci that affect cortical surface area and thickness42. The study revealed many loci where variants were associated with surface area. Most interestingly, genetic correlations indicated that the variants associated with a smaller global surface area overlapped more with the variants involved in insomnia6 than with variants of any other included symptom or disorder. In light of (1) the strong genetic correlation between insomnia and cortical surface area, (2) the genetic heritability of surface area, and (3) the more externally driven variability of cortical thickness, we consider it likely that overlapping neurobiological mechanisms predispose to both a smaller cortical surface area and more severe insomnia symptoms in MDD. We cannot fully exclude, however, the possibility that insomnia causes a reduction of cortical surface area as secondary process.

We found smaller surface areas of several cortical regions to be associated with insomnia severity in MDD patients; such associations were, however, not found in non-depressed samples. Few studies investigated cortical surface area in relation to insomnia complaints. Lim et al.43 found that sleep fragmentation was nominally associated with lower surface area in the banks of the superior temporal sulcus and pars orbitalis. While we did not find cortical thickness to be associated with insomnia severity in MDD, we did find insomnia severity to be associated with thickness alterations in the entorhinal cortex and the rACC in our healthy control sample. Several studies have reported an association between thickness and insomnia severity in non-depressed people43,44,45. More specifically within insomnia patients, one study found thinning in the ACC, precentral cortex, and lateral prefrontal cortex18, while in contrast another study found thickening in several areas, including the orbital frontal cortex, rACC, middle cingulate cortex, insula, superior parietal lobule, and fusiform area19. Concertedly, these findings provide support for a double dissociation suggesting a depression-specific association of insomnia severity with cortical surface area and an association of insomnia severity with cortical thickness in non-depressed people.

Reduced surface area of the medial OFC, however, was found to be related to insomnia severity in both MDD patients and in healthy controls in our study. One study found reduced GM in the medial OFC in co-morbid depression and insomnia patients compared to insomnia or depressed patients without comorbid disorders21. Alterations in the medial OFC might have a symptom-specific role that is similar in in both insomnia and depressed patients.

The cortical regions for which a smaller surface area predicted more severe insomnia are involved in a wide range of functions, including emotional processing (medial OFC, frontal pole, insula), attentional processing and interoceptive awareness (insula), and cognitive control (inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis, insula, parietal regions)46,47. It may—at first glance—be surprising that insomnia severity is significantly associated with the surface area of regions that are primarily involved in these processes, while overall depression severity is not. Recent insights, however, suggest that insomnia involves altered emotion regulation and interoception rather than deficits in sleep regulation per se48,49,50, which is again supported by our findings of reduced surface area in regions involved in emotional processing.

The current study has several limitations. First, we had limited information on sleep in our sample: only three HDRS items about insomnia. It would have been interesting to evaluate whether cortical surface areas showed similar associations with other measures of sleep, as could be derived from sleep diaries, actigraphy, or polysomnography. Even so, actigraphic and polysomnographic measures of sleep hardly correlate with the subjective complaints that diagnostically define insomnia51. By contrast, subjective complaints recorded in sleep diaries strongly correlate with the insomnia items of the HDRS27. Second, the characteristics of the HCP healthy controls were somewhat different: they were younger, scanned on a different scanner, and asked different insomnia questions than in the ENGIMA MDD sample. Nevertheless, these results still provide valuable insight into how insomnia-related brain alterations may be different in people with MDD than in people without MDD. Third, poor sleep quality might be associated with obstructive sleep apnea, a late chronotype, and sleep duration. Sleep apnea and chronotype have been associated with less GM52 and a thinner cortex53,54,55; however, as far as we know no studies have associated these variables with cortical surface area. Insomnia severity might also be associated with sleep duration; however, in a large study of MDD patients the shared variance between insomnia severity and sleep duration was limited (20%)56, suggesting discernable dimensions of sleep. Unfortunately, sleep apnea, chronotype, and sleep duration were not systematically assessed in our sample. It would be interesting to evaluate whether our findings are better explained by these variables than by quality of sleep. Lastly, other variables could potentially have contributed to individual differences in our dataset, such as handedness57, oral contraceptive use58, medical comorbidities, or dementia59,60,61,62,63. Future studies could take these variables into account. A major strength of our study is that we obtained data from a large representative sample of MDD patients from 15 different sites, supporting the robustness and generalizability of our results. The robustness of our findings is further supported by the lack of interaction effects of surface area with antidepressant use, depression recurrence, or age of onset of depression.

In conclusion, our study showed that insomnia is more severe in patients with MDD who have a smaller cortical surface area, in particular of the right insula, left inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis, left frontal pole, right superior parietal cortex, right medial OFC, and right supramarginal gyrus. The better specificity of these associations with insomnia severity than with total depression severity highlights the possibility that insomnia could represent a symptom cluster of MDD with a distinct neurobiological underpinning.

Code availability

Analysis scripts are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Benca, R. M., Obermeyer, W. H., Thisted, R. A. & Gillin, J. C. Sleep and psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49, 651–668 (1992).

Baglioni, C. et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J. Affect. Disord. 135, 10–19 (2011).

Thase, M. E. et al. Which depressed patients will respond to interpersonal psychotherapy? The role of abnormal EEG sleep profiles. Am. J. Psychiatry 154, 502–509 (1997).

Cunningham, J. E. A. & Shapiro, C. M. Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) to treat depression: a systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 106, 1–12 (2018).

Blanken, T. F. et al. Introducing network intervention analysis to investigate sequential, symptom-specific treatment effects: a demonstration in co-occurring insomnia and depression. Psychother. Psychosom. 88, 52–54 (2019).

Hammerschlag, A. R. et al. Genome-wide association analysis of insomnia complaints identifies risk genes and genetic overlap with psychiatric and metabolic traits. Nat. Genet. 49, 1584–1592 (2017).

Jansen, P. R. et al. Genome-wide analysis of insomnia in 1,331,010 individuals identifies new risk loci and functional pathways. Nat. Genet. 51, 394–403 (2019).

Altena, E., Vrenken, H., Van Der Werf, Y. D., van den Heuvel, O. A. & Van Someren, E. J. Reduced orbitofrontal and parietal gray matter in chronic insomnia: a voxel-based morphometric study. Biol. Psychiatry 67, 182–185 (2010).

Winkelman, J. W. et al. Increased rostral anterior cingulate cortex volume in chronic primary insomnia. Sleep 36, 991–998 (2013).

Joo, E. Y. et al. Brain gray matter deficits in patients with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep 36, 999–1007 (2013).

Li, M. et al. Altered gray matter volume in primary insomnia patients: a DARTEL-VBM study. Brain Imaging Behav. 12, 1759–1767 (2018).

Bumb, J. M. et al. Pineal gland volume in primary insomnia and healthy controls: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Sleep. Res. 23, 274–280. (2014).

Li, M. et al. Abnormalities of thalamus volume and resting state functional connectivity in primary insomnia patients. Brain Imaging Behav. 13, 1193–1201 (2019).

Kang, J. M. et al. Low white-matter integrity between the left thalamus and inferior frontal gyrus in patients with insomnia disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 43, 170195 (2018).

Riemann, D. et al. Chronic insomnia and MRI-measured hippocampal volumes: a pilot study. Sleep 30, 955–958 (2007).

Joo, E. Y., Kim, H., Suh, S. & Hong, S. B. Hippocampal substructural vulnerability to sleep disturbance and cognitive impairment in patients with chronic primary insomnia: magnetic resonance imaging morphometry. Sleep 37, 1189–1198 (2014).

Leerssen, J. et al. Increased hippocampal-prefrontal functional connectivity in insomnia. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 160, 144–150 (2019).

Suh, S., Kim, H., Dang-Vu, T. T., Joo, E. & Shin, C. Cortical thinning and altered cortico-cortical structural covariance of the default mode network in patients with persistent insomnia symptoms. Sleep 39, 161–171 (2016).

Yu, S. et al. Gray matter hypertrophy in primary insomnia: a surface-based morphometric study. Brain Imaging Behav. 14, 1309–1317 (2020).

Vassilopoulou, K. et al. A magnetic resonance imaging study of hippocampal, amygdala and subgenual prefrontal cortex volumes in major depression subtypes: melancholic versus psychotic depression. J. Affect. Disord. 146, 197–204 (2013).

Yu, S. et al. The orbitofrontal cortex gray matter is associated with the interaction between insomnia and depression. Front. Psychiatry 9, 651 (2018).

Benjamins, J. S. et al. Insomnia heterogeneity: characteristics to consider for data-driven multivariate subtyping. Sleep. Med. Rev. 36, 71–81 (2017).

Blanken, T. F. et al. Insomnia disorder subtypes derived from life history and traits of affect and personality. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 151–163 (2019).

Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 23, 56–62 (1960).

Van Essen, D. C. et al. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: an overview. Neuroimage 80, 62–79 (2013).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. III, Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Manber, R. et al. Assessing insomnia severity in depression: comparison of depression rating scales and sleep diaries. J. Psychiatr. Res. 39, 481–488 (2005).

Achenbach T. M. The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): Development, Findings, Theory, and Applications (University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, 2009).

Schmaal, L. et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 900–909 (2017).

Schmaal, L. et al. Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder working group. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 806–812 (2016).

Glasser, M. F. et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 80, 105–124 (2013).

Fischl, B. et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 33, 341–355 (2002).

Desikan, R. S. et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 31, 968–980 (2006).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Leon, A. C. & Heo, M. Sample sizes required to detect interactions between two binary fixed-effects in a mixed-effects linear regression model. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 53, 603–608 (2009).

Button, K. S. et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 365 (2013).

Insel, T. et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a New Classification Framework for Research on Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2010).

Cuthbert, B. N. & Insel, T. R. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med. 11, 126 (2013).

Wierenga, L. M., Langen, M., Oranje, B. & Durston, S. Unique developmental trajectories of cortical thickness and surface area. Neuroimage 87, 120–126 (2014).

Sanabria-Diaz, G. et al. Surface area and cortical thickness descriptors reveal different attributes of the structural human brain networks. Neuroimage 50, 1497–1510 (2010).

Winkler, A. M. et al. Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage 53, 1135–1146 (2010).

Grasby, K. L. et al. The genetic architecture of the human cerebral cortex. Science 367, eaay6690 (2020).

Lim, A. S. P. et al. Regional neocortical gray matter structure and sleep fragmentation in older adults. Sleep 39, 227–235 (2016).

Kocevska, D. et al. The developmental course of sleep disturbances across childhood relates to brain morphology at age 7: the Generation F study. Sleep 40, zsw022 (2017).

Sexton, C. E., Storsve, A. B., Walhovd, K. B., Johansen-Berg, H. & Fjell, A. M. Poor sleep quality is associated with increased cortical atrophy in community-dwelling adults. Neurol 83, 967–973 (2014).

Damasio, A. R. et al. Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self-generated emotions. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 1049 (2000).

Menon, V. & Uddin, L. Q. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 655–667 (2010).

Wassing, R. et al. Slow dissolving of emotional distress contributes to hyperarousal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2538–2543 (2016).

Wei, Y. et al. I keep a close watch on this heart of mine: increased interoception in insomnia. Sleep 39, 2113–2124 (2016).

Wassing, R., Benjamins, J. S., Talamini, L. M., Schalkwijk, F. & Van Someren, E. J. W. Overnight worsening of emotional distress indicates maladaptive sleep in insomnia. Sleep 42, zsy268 (2019).

Rosa, R. R. & Bonnet, M. H. Reported chronic insomnia is independent of poor sleep as measured by electroencephalography. Psychosom. Med. 62, 474–482 (2000).

Shi, Y. et al. A meta-analysis of voxel-based brain morphometry studies in obstructive sleep apnea. Sci. Rep. 7, 10095 (2017).

Joo, E. Y., Jeon, S., Kim, S. T., Lee, J.-M. & Hong, S. B. Localized cortical thinning in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 36, 1153–1162 (2013).

Macey, P. M. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and cortical thickness in females and males. PLoS ONE 13, e0193854 (2018).

Rosenberg, J., Jacobs, H. I. L., Maximov, I. I., Reske, M. & Shah, N. J. Chronotype differences in cortical thickness: grey matter reflects when you go to bed. Brain Struct. Funct. 223, 3411–3421 (2018).

van Mill, J. G., Hoogendijk, W. J., Vogelzangs, N., van Dyck, R. & Penninx, B. W. Insomnia and sleep duration in a large cohort of patients with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 239–246 (2010).

Willems, R. M., der Haegen, L. V., Fisher, S. E. & Francks, C. On the other hand: including left-handers in cognitive neuroscience and neurogenetics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 193–201 (2014).

Petersen, N., Touroutoglou, A., Andreano, J. M. & Cahill, L. Oral contraceptive pill use is associated with localized decreases in cortical thickness. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 2644–2654 (2015).

Storsve, A. B. et al. Differential longitudinal changes in cortical thickness, surface area and volume across the adult life span: regions of accelerating and decelerating change. J. Neurosci. 34, 8488–8498 (2014).

Dotson, V. M. et al. Age differences in prefrontal surface area and thickness in middle aged to older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7, 250 (2016).

Sepulcre, J. et al. Neurogenetic contributions to amyloid beta and tau spreading in the human cortex. Nat. Med. 24, 1910–1918 (2018).

Sepulcre, J. et al. Hierarchical organization of tau and amyloid deposits in the cerebral cortex. JAMA Neurol. 74, 813–820 (2017).

Cho, H. et al. Predicted sequence of cortical tau and amyloid-β deposition in Alzheimer disease spectrum. Neurobiol. Aging 68, 76–84 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 671084 - INSOMNIA, J.L., T.F.B., E.J.W.V.S.) and from the VU University Amsterdam University Research Fellowships (J.L., T.F.B.). The ENIGMA-MDD Working Group is supported by NIH Consortium grant U54 EB020403, R01 MH116147, P41 EB015922 (P.M.T., N.J.) and R01 MH117601 (N.J., L.S.). This work was further supported by a “Miguel Servet-II” contract from the Spanish Ministry of Health (CP16-00020) and partly funded by PI13/01057 (M.J.P.), Wellcome Trust Grant 10436/Z/14/Z (A.M.M.), and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 602450. This paper reflects only the author’s views and the European Union is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. This work was also supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award 104036/Z/14/Z and the IMAGEMEND grant (H.C.W.); Branch Out Neurological Foundation, Children’s Hospital Aid Society (F.P.M.); Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) Professorship grant (T.F.); German Research Foundation (DFG, grant FOR2107 KR 3822/5-1 and KR 3822/7-2 to A.K.; DFG, grant FOR2107 KI 588/14-1 and KI 588/14-2 to T.K.; DFG, grant FOR2107 NE 2254/1-2 to I.N.; DFG, grant FOR2107 DA1151/5-1 and DA1151/5-2 to U.D.); NIMH grant R01 085667, the Dunn Foundation and the Pat Rutherford, Jr. Endowed Chair in Psychiatry (J.C.S.); German Research Foundation (SFB-TRR58, Projects C09 and Z02 to U.D.) and the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the medical faculty of Münster (grant Dan3/012/17 to U.D.); Optimising Personalised Care, at scale, for Young People with Emerging Mood Disorders $951,005 over 5 years (2018-2022) (APP1136259, I.B.H.). Russian Science Foundation grant #16-15-00128 (L.A.); UK Medical Research Council, Grant number G0701421, (B.R.G.); NIMH Grants R01-MH59259 and R37-MH101495 (I.H.G.); NIA T32AG058507, NIH/NIMH 5T32MH073526, NIH grant U54EB020403 from the Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Program (C.R.K.C.); Wellcome Trust Strategic Award “STratifying Resilience and Depression Longitudinally” (STRADL) Reference 104036/Z/14/Z (E.H.); Dr Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation (M.A.H.); Innovative Medical Research (RE111604 and RE111722 to R.R.); Medical Review, Sogen-sha (N.W.); Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute (Q.M.). MPIP data were in part provided by the Munich Antidepressant Response Signature study, supported by a grant of the Exzellenz-Stiftung of the Max Planck Society and funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the framework of the National Genome Research Network (NGFN), FKZ 01GS0481. Data were provided (in part) by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 NIH Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I.B.H. has previously led community-based and pharmaceutical industry-supported (Wyeth, Eli Lily, Servier, Pfizer, AstraZeneca) projects focused on the identification and better management of anxiety and depression. He was a member of the Medical Advisory Panel for Medibank Private until October 2017, a Board Member of Psychosis Australia Trust, and a member of Veterans Mental Health Clinical Reference group. He is the Chief Scientific Advisor to, and an equity shareholder in, Innowell. Innowell has been formed by the University of Sydney and PwC to deliver the $30 m Australian Government-funded “Project Synergy.” Project Synergy is a 3-year program for the transformation of mental health services through the use of innovative technologies. C.R.K.C. received partial research support from Biogen, Inc. (Boston, USA) for work unrelated to the topic of this manuscript. The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leerssen, J., Blanken, T.F., Pozzi, E. et al. Brain structural correlates of insomnia severity in 1053 individuals with major depressive disorder: results from the ENIGMA MDD Working Group. Transl Psychiatry 10, 425 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01109-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01109-5

This article is cited by

-

Insomnische Symptome und Suizidalität – Zusammenhänge und Management

neuropsychiatrie (2023)

-

Aberrant intrinsic hippocampal and orbitofrontal connectivity in drug-naive adolescent patients with major depressive disorder

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2023)

-

The moderating effect of prefrontal response to sleep-related stimuli on the association between depression and sleep disturbance in insomnia disorder

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Polygenic risk scores for major psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders contribute to sleep disturbance in childhood: Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study

Translational Psychiatry (2021)