Abstract

As a hallmark of electronic correlation, spin-charge interplay underlies many emergent phenomena in doped Mott insulators, such as high-temperature superconductivity, whereas the half-filled parent state is usually electronically frozen with an antiferromagnetic order that resists external control. We report on the observation of a positive magnetoresistance that probes the staggered susceptibility of a pseudospin-half square-lattice Mott insulator built as an artificial SrIrO3/SrTiO3 superlattice. Its size is particularly large in the high-temperature insulating paramagnetic phase near the Néel transition. This magnetoresistance originates from a collective charge response to the large longitudinal spin fluctuations under a linear coupling between the external magnetic field and the staggered magnetization enabled by strong spin-orbit interaction. Our results demonstrate a magnetic control of the binding energy of the fluctuating particle-hole pairs in the Slater-Mott crossover regime analogous to the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer-to-Bose-Einstein condensation crossover of ultracold-superfluids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While a huge variety of unusual symmetry-breaking orderings can emerge as the ground state of correlated electrons, the disordered state above the phase transition is often even more enigmatic due to fluctuations that are challenging for experimental characterization and theoretical description1. This is particularly true when strong interplay between the spin and charge degrees of freedom is in play, such as the fascinating normal state of high-temperature superconductors2. One of the profound outcomes of the electronic spin-charge interplay is the Mott insulating state at half-filling3, where charge localization gives rise to local magnetic moments. The local magnetic moments are thus effectively local particle–hole pairs, and they interact antiferromagnetically with their neighbors and order below the Néel temperature TN (Fig. 1a). Correspondingly, fluctuations that excite localized charges into the electron–hole continuum above the Mott gap would lead to spatial fluctuations in the size of the magnetic moments, and vice versa (Fig. 1b). It is, however, difficult to detect and exploit this interplay between spin and charge fluctuations because the charge degree of freedom is often frozen in practical Mott materials, like the parent compounds of high-Tc cuprates4, which are often deep inside the Mott regime. Moreover, the local moments are shielded from the external magnetic field by the antiferromagnetic (AFM) interaction.

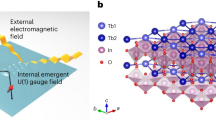

Superlattice as a Mott-type AFM insulator. a–c Cartoons of a half-filled Hubbard system. a Coulomb potential (upward curve) confines one electron–hole pair on each lattice site in an AFM insulating ground state. b Magnetic moments decrease with expanded electron-hole pairs or disappear with excitations into the electron–hole continuum. c A staggered magnetic field reinforces the staggered moments and the electron–hole pairing. d Schematics of the crystal and magnetic structures of the SL. The canted moment M is represented as a black arrow. e T-dependence of the normalized in-plane resistance (solid). It can be well described by the thermal activation model (dash) above TN (200–300 K), which is extrapolated below TN. Inset shows measurements with and without an in-plane 8 T magnetic field. f T-dependence of the (0.5 0.5 2) magnetic peak intensity and the XMCD. Inset shows a representative L-scan at 10 K. The XMCD is squared since the magnetic peak intensity is proportional to the AFM OP squared.

5d transition metal oxides provide an intriguing alternative for exploiting such spin-charge interplay5,6,7,8. In particular, tetravalent iridates can often be considered as effective half-filled single-band systems9,10,11,12 similar to the 3d cuprates13. As a result, some of their AFM insulating ground state properties can be described by a Hubbard Hamiltonian at the strong coupling limit, i.e., a Mott insulator. On the other hand, the significantly reduced Coulomb interaction and larger extension of the 5d orbitals shift these materials toward the Slater regime corresponding to the weak-coupling limit. Both of these two perturbative approaches predict antiferromagnetic insulating ground state, but neither of them provides a complete description of the experimentally observed behaviors14. For instance, the charge gap is often found to be reduced from the Mott limit and of a similar size to the magnon bandwidth15. Meanwhile, unlike the Slater limit, the insulating behavior and the magnetic moments persist above TN16,17,18. These characters indicate that these materials belong to the crossover regime between the Mott and Slater limits, where neither the Coulomb potential nor the kinetic energy dominates, allowing charge fluctuations to significantly reduce the longitudinal spin stiffness. The Slater–Mott crossover regime is in fact the particle–hole counterpart of the famous Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS)-to-Bose–Einstein condensation (BEC) crossover observed in ultracold-superfluids19,20,21. One may thus anticipate strong spin-charge fluctuations above TN that are absent in conventional Mott materials and must be considered by including both spin and charge degrees of freedom in the model Hamiltonian.

In this article, we report an experiment-theory-combined investigation on the spin and charge interlay in a square-lattice iridate built as an artificial superlattice (SL) of SrIrO3 and SrTiO3, which is well described by a two-dimensional (2D) single-band Hubbard model in the crossover regime between the Mott3 and the Slater21 limits. Our results show that, while both limits are adiabatically connected, the strong spin-charge fluctuations in the paramagnetic semiconducting state above TN hold the key that characterizes the crossover regime. We find that these spin-charge fluctuations can be controlled with an external magnetic field, which couples linearly to the staggered magnetization (Fig. 1c) due to the strong spin–orbit interaction (SOI), and induces a large positive magnetoresistance (MR) above TN. The effects are well reproduced by our calculation, which captures the spatial AFM fluctuations of the paramagnetic state.

Results

SrIrO3/SrTiO3 superlattice as a Mott-type AFM insulator

The SL consists of monolayers of SrIrO3 and SrTiO3 perovskite stacked alternately on a SrTiO3 substrate (Fig. 1d). The SL structure is effectively an artificial crystal of Sr2IrTiO6 with a confined square lattice of corner-sharing IrO6 octahedra in the unit cell22,23. Moreover, the large SOI of the Ir4+ ion removes the t2g orbital degeneracy and stabilizes a half-filled Jeff = 1/2 state (Supplementary Fig. 1), affording a prototypical single-band system7,8,9,10,14,24, which is partially similar to the parent phase of cuprates13, but with a spin-dependent hopping. The SL exhibits an AFM insulating ground state, including a monotonic exponential resistance increase with reducing temperature T (Fig. 1e) and multiple (0.5 0.5 integer) magnetic reflections (inset of Fig. 1f). The insulating character of the SL is consistent with the dimensional crossover from bulk perovskite SrIrO3 toward the ultrathin limit25,26. The T-dependence of the (0.5 0.5 2) peak intensity indicates TN ~ 150 K (Fig. 1f), in agreement with previous reports22,23. Furthermore, the AFM order is accompanied with a weak uniform spontaneous magnetization within the ab-plane arising from spin canting due to SOI (Supplementary Fig. 2). The zero-field canting angle is temperature independent and it is determined by the magnitude of the SOI10,27.

Anomalous positive MR at T > T N

Despite the characteristic AFM Mott insulating ground state, the charge transport reveals an anomalous T-dependence that cannot be explained within the Mott-Heisenberg scheme. In particular, the insulating behavior is clearly enhanced upon cooling below TN in comparison to the data above TN that exhibits a thermally activated behavior with a constant activation energy (Fig. 1e). More interestingly, the resistance can be significantly enhanced near TN under an in-plane magnetic field (inset of Fig. 1e). This positive MR is in stark contrast to conventional AFM semiconductors and other Mott insulators28,29, where a negative MR is usually observed due to the field-induced suppression of transverse spin fluctuations. Figure 2a shows the T-dependent MR defined as [R(B) – R(B = 0 T)]/R(B = 0 T) under different field strengths. The MR is always positive and displays a strong anomalous behavior where the MR above TN rapidly increases upon cooling and reaches a maximum around TN, indicative of a large field-induced enhancement of the paramagnetic insulating state. The magnitude of the positive anomalous MR is indeed remarkably large, reaching 14% at 14 T or equivalently ~1%/T, considering the absence of spontaneous long-range magnetic order above TN. In other materials, MR of this magnitude in the paramagnetic state is usually negative and relates to insulator-to-metal phase transition30,31, highlighting the unusual combination of robust insulating/semiconducting behavior and large positive MR that is present in the SL.

MR and XMCD measurements. (a) T-dependent MR under various in-plane (solid line) magnetic fields and a 14 T out-of-plane (dashed line) magnetic field. (b) In-plane uniform susceptibility χ extracted from the in-plane field-induced XMCD difference (Supplementary Fig. 3). The solid line is a guide to the eye. In-plane magnetic field dependences of MR (c) at various temperatures and XMCD (d) at 150 K. The error bars come from the statistical averaging every 0.5 T.

To reveal the role of the external field, we measured x-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) at the Ir L3-edge. XMCD measures the uniform magnetization, which at zero magnetic field characterizes the canted component of the spontaneous AFM order parameter (OP) as can be seen from its similar T-dependence to the AFM Bragg peak (Fig. 1f). The field-induced XMCD variation is thus proportional to the uniform susceptibility χ, which indeed displays a clear maximum around TN (Fig. 2b). The XMCD shows a positive linear increase as the field scans from 0 to 5 T near TN (Fig. 2d). Therefore, based on the extracted χ from XMCD and the thermally activated resistivity above TN, we estimate the MR of ~1%/T corresponds to ~0.12 meV enhancement of the activation energy for every ~0.02 × 10−3 meV increase of the Zeeman energy \(\mu _0 \cdot \chi \cdot {\mathbf{H}}^2\), i.e., a response coefficient of ~6000 in energy scale. In other words, the effect of the external magnetic field is amplified by more than three orders of magnitude in the electronic response due to the strong interplay between spin and charge. Interestingly, since the canting angle ϕ ~ 10o is determined by a combination of the lattice distortion and the strong SOI10,27, and is practically unchanged for these field values32, the measured uniform susceptibility χ becomes proportional to the staggered susceptibility χst near TN with a proportionality factor sin2ϕ ~ 0.03 (refs. 27,33). The similar T-dependence of χ and MR suggests that the external field triggers the anomalous charge response near TN via the large staggered susceptibility. In other words, the MR above TN is the charge response to the large relative increase of the staggered magnetization induced by the external field. To verify this mechanism, we oriented the field along the c-axis where the spin canting is much smaller (Supplementary Fig. 2) and the uniform susceptibility is not sensitive to the staggered susceptibility. The MR becomes strongly suppressed (Fig. 2a), resembling the situation of applying the field to a collinear antiferromagnet. This can indeed be seen from the absence of the MR effect in a square-lattice iridate with a collinear magnetic structure34.

Modeling the Slater–Mott crossover regime

The large anomalous MR in the paramagnetic phase is clearly incompatible with a Mott-Heisenberg regime where charge degrees of freedom are basically frozen because of a charge gap that is much larger than the hopping amplitude. In the opposite weak-coupling limit or Slater regime21, the charge gap arises from the band reconstruction induced by the AFM ordering and it is directly proportional to the staggered magnetization Mst. Correspondingly, an external modulation of Mst is expected to modulate the charge gap causing a charge response that is maximized at TN. The shortcoming of this picture is that the system becomes metallic above TN and a field-induced gap much smaller than TN does not necessarily affects the resistivity, which clearly would not account for our observations. The coexistent characteristics of the Slater and the Mott regimes indicate that the observed behavior can only be consistent with the crossover regime (see below). However, modeling the spin-charge interplay and the thermodynamic properties in this intermediate-coupling regime is particularly challenging, especially above TN, because of the lack of a small control parameter19,20,35. In other words, to properly capture all the characteristics and the magnetoelectronic response in this regime, one must account for the spatial longitudinal and angular spin fluctuations of the magnetic moments that emerge when the temperature becomes lower than the charge gap, but still well above TN.

We capture these fluctuations by a semi-classical approach where the interaction term of a Hubbard-like model is decoupled via a Hubbard-Stratonovich (HS) transformation (Methods). The motion of thermally activated electrons above the charge gap is then described by an effective quadratic Hamiltonian: fermions propagate under the effect of a fluctuating potential caused by an effective exchange coupling to the underlying HS vector field. The semi-classical approximation arises from the fact that the HS vector field is not allowed to fluctuate along the imaginary time direction36,37,38. Specifically, the effective single-band Hubbard model for the pseudospin-half square-lattice iridates has been well established and can be written as27,39,40

with the nearest-neighbor \(\langle ij\rangle\) hopping amplitude t, the onsite Coulomb potential U, and the magnetic field h that couples with the electron spin \({\mathbf{s}}_j = \frac{1}{2}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{\alpha \beta } {c_{j\alpha }^\dagger {\mathbf{\upsigma }}_{\alpha \beta }c_{j\beta }}\). The wave vector Q = (π, π) distinguishes the two sublattices and the phase factor \({\mathrm{e}}^{{\mathrm{i}}\,\varphi \,{\mathrm{exp}}\left( {{\mathrm{i}}{\mathbf{Q}} \cdot {\mathbf{r}}_i} \right)\sigma ^{\mathrm{z}}}\) represents the spin-dependent hopping enabled by SOI and octahedral rotation (Fig. 3)41. Unlike the usual spin-half Hubbard model, this phase factor renders complex hopping integrals for different spins due to the spin–orbit-entangled Jeff = 1/2 wavefunctions. It is important to note that the in-plane spin canting in the AFM ground state is ultimately driven by this spin-dependent hopping and the angle φ of the phase factor determines the canting angle ϕ at zero field42,43. At finite fields, it determines the ratio of the uniform susceptibility and the staggered susceptibility. Therefore, the spin-dependent hopping allows the external magnetic field to couple linearly with the staggered magnetization through the uniform component at any temperature. To reveal this point, we perform a staggered reference frame transformation, \(\tilde c_{j\alpha } = \mathop {\sum }\nolimits_\beta \left[ {{\mathrm{e}}^{ - {\mathrm{i}}\frac{\varphi }{2}{\mathrm{exp}}\left( {i{\mathbf{Q}} \cdot {\mathbf{r}}_j} \right)\sigma ^z}} \right]_{\alpha \beta }c_{j\beta }\), to convert the global spin frame into the local spin frame depicted in Fig. 3. In the new reference frame, the Hamiltonian becomes:

where \(\tilde s_j^{\mathrm{z}}\) and \({\tilde{\mathbf{s}}}_j^ \bot\) are the out-of-plane and in-plane components of the transformed spin \({\tilde{\mathbf{s}}}_j = \frac{1}{2}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{\alpha \beta } {\tilde c_{j\alpha }^\dagger \,{\boldsymbol{\sigma}} _{\alpha \beta }\tilde c_{j\beta }}\), and hz and \({\mathbf{h}}^ \bot\) are the out-of-plane and in-plane components of the external field. Interestingly, the phase factor is gauged away by this transformation of the reference frame10,27,32,44,45, which uncovers the Hubbard model with the usual spin-independent hopping and a linear coupling between the external field and the staggered magnetization scaled by \({\mathrm{sin}}\varphi\).

Charge hopping in spin-up (red) and spin-down channels (blue) in different spin frames. In the global spin frame (left panel), charge hopping bears an alternating phase factor when circling around the square lattice. This phase factor is gauged away in the rotated local spin frame (right panel), leading to an isotropic Hubbard model27,33. The annihilation operators \(\tilde c_{j\alpha }\), in the local frame are transformed from cj,β in the global frame according to the shown transformation.

Figure 4b shows the longitudinal resistivity ρ computed with the Kubo formula46 on a square lattice of 64 × 64 atoms for the intermediate-coupling strength and Hamiltonian parameters relevant to the present SL (Methods). ρ indeed displays an insulating exponential increase when decreasing temperature. From the T-dependent Mst, we identified a non-zero AFM transition temperature around T/t ~ 0.1 (Fig. 4c) after including the easy-plane anisotropy that arises from the Hund’s coupling (Methods). Under an in-plane magnetic field, Mst is clearly enhanced and it becomes finite above TN. The response (Fig. 4d) exhibits a T-dependence typical of the staggered susceptibility, similar to the XMCD data. The calculated MR at temperatures above TN is also positive and it reaches a maximum at the AFM transition in agreement with the experimental observation (Fig. 2a). In stark contrast, Mst and ρ remain almost unchanged under the effect of an out-of-plane field due to the lack of the staggered field effect that is expected from Eq. (2). We note that we have used a much larger field than the experimental value because of limitations in the numerical accuracy of our unbiased stochastic estimator of the conductivity. Additionally, extrinsic effects that may dominate the conductivity well below TN, such as magnetic domains or domain walls47,48, cannot be captured by our model. Nevertheless, the remarkable agreement between experiment and theory at temperatures above and near TN, where magnetic domains are absent, demonstrates that the MR is an indirect electronic probe of the staggered susceptibility whenever the field couples linearly to Mst.

Theoretical calculations. a A generic phase diagram of the Slater–Mott crossover. The charge gap Δ is shown with TN and Mst as a function of U/t. T-dependent resistivity (b), Mst (c) and carrier density n (e) calculated at zero field (black circles), in-plane field (red up triangles) and out-of-plane field (blue down triangles) for h ≈ 0.1t and U = 3t. T-dependent MR (circles) and field-induced Mst-variation (diamonds) (d), and field-induced n-variation (f) under an in-plane (full) and out-of-plane (open) field. The error bars represent the statistical error.

To gain microscopic insights, we have also computed the T-dependence of the thermally activated carriers n (free particles/holes) using model (1). As shown in Fig. 4e, the suppression of n accelerates upon cooling toward the AFM transition, below which n quickly drops to zero. This behavior illustrates the unique character of the Slater–Mott crossover regime where a large number of particle–hole pairs are pre-formed well above TN with a fluctuating coherence length of several lattice spaces. This size fluctuation and the corresponding longitudinal spin fluctuations are critically suppressed upon cooling toward TN. By inducing a finite Mst, the in-plane magnetic field further suppresses n through increasing the binding energy of the particle–hole pairs. This tunability maximizes near TN (largest AFM susceptibility), while it decreases upon rotating the field to the out-of-plane direction (Fig. 4f). This analysis uncovers the role of the SOI, which enables a linear coupling between the uniform field and the staggered magnetization and therefore a relatively large positive anomalous MR due to the large longitudinal staggered susceptibility of the Slater–Mott crossover regime.

Discussion

From the experimental results and the theoretical simulations, we can conclude that the two basic ingredients of the positive anomalous MR are (1) the strong interplay between spin and charge in the paramagnetic state of the Slater–Mott crossover regime, and (2) the spin-dependent hopping enabled by the strong SOI and the lattice structure, emerging as ferromagnetic canting in the ground state. While the former ingredient is present in many correlated systems, the latter one is subject to multiple competing interactions, such as easy-plane vs. easy-axis anisotropy. The structure of our SL is designed to minimize such competition as the octahedral network is rotated in the same way among all IrO6 layers (Fig. 1d)49. For comparison, the pseudospin-half iridate Sr2IrO4 has a much more complicated layered structure and a magnetic unit cell that contains four IrO6 layers with a substantial and nontrivial interlayer interaction that favors cancellation of the canted moments33. These differences explain why the MR of Sr2IrO4 is negative and governed by the transverse spin fluctuations50,51,52,53.

Note that, although the magnitude of the observed anomalous MR is smaller than the GMR54 and CMR effects31 of magnetic metals, distinct MR effects often indicate a new physical mechanism, like the one present in the recently discovered spin-Hall MR effect55,56. In our case, the sensitivity of MR to the longitudinal spin fluctuations provides an efficient electronic probe of the usually elusive staggered susceptibility of Mott-type insulating materials. This magnetoelectronic effect provides a mechanism that is fundamentally distinct from that in itinerant magnets and conventional magnetic semiconductors29,57, where the magnetic moments and the carriers are two separate subsystems and orientation control of the OP is the dominant mechanism for modifying the carrier transport28. In contrast, the spin and the charge are necessarily provided by the same electrons in Hubbard-like systems. The Mott semiconductor that emerges in the Slater–Mott crossover regime has the best performance near TN, which is expected to be maximized in this regime (Fig. 4a). Moreover, since longitudinal fluctuations have higher frequency than the transverse fluctuations58, the Slater–Mott crossover regime may enable high-speed electronics. If combined with orientation control of the AFM moments59,60, it may pave a way to merge the information processing and storage functionalities in a single material with enhanced device density.

In summary, we have demonstrated the ability to control resistivity by exploiting the strong interplay between the staggered magnetization and the effective Coulomb potential in a quasi-two-dimensional AFM Mott insulator. The strong longitudinal spin fluctuations in the Slater–Mott crossover regime are exposed to external field by SOI and enable a significant MR that peaks around TN. This magnetoelectronic effect has not been observed in strongly correlated Mott insulators, such as cuprates61,62, or in weakly correlated Slater insulators63, highlighting the nontrivial spin-charge fluctuations of the crossover regime and the importance of strong SOI. The work thus opens a door for designing AFM electronics in spin–orbit-entangled correlated materials.

Methods

Sample synthesis

The superlattice of [(SrIrO3)1/(SrTiO3)1] was fabricated by means of pulsed laser deposition on a single crystal SrTiO3 (001) substrate. The deposition process was in-situ monitored through an equipped reflection high-energy electron diffraction unit. This guarantees an accurate control of the atomic stacking sequence (60 repeats). Optimized growth temperature, oxygen pressure, and laser fluence are 700 °C, 0.1 mbar and 1.8 J/cm2, respectively. Detailed structural characterizations can be found in ref. 23.

Materials characterizations

The sample magnetization was characterized with a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (Quantum design). In-plane and out-of-plane remnant magnetization were recorded during zero-field warming process. The sample resistance was measured by using the standard four-probe method on a physical properties measurement system (PPMS, Quantum design) and a PPMS Dynacool. For the in-plane MR measurements, the magnetic field is applied along the STO (100) direction. The X-ray absorption (XAS) and X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) data was collected around the Ir L3- and L2-edges on beamline 4IDD at the Argonne National Laboratory, which features a high magnetic field strength of 6 T. For these measurements, the samples were monitored in a grazing incidence geometry and a fluorescence yield mode was adopted. Magnetic scattering experiments near Ir L3-edge were performed on beamline 6IDB, at the Advanced Photon Source of Argonne National Laboratory. A pseudo-tetragonal unit cell a × a × c (a = 3.905 Å, c = 3.954 Å)23 was used to define the reciprocal lattice notation.

Numerical simulation

To account for the easy-plane anisotropy arising from Hund’s coupling, the following term is included in the total Hamiltonian10:

where the + (−) sign is taken for bonds along the x (y) direction.

To study the electrical response, we first perform a Hubbard–Stratonovich transformation to the Hamiltonian H + HA, which gives the spin fermion Hamiltonian36,37,38

where the local auxiliary field mi is a classical vector in R3.

The equilibrium configurations of mi are sampled via the stochastic Ginzburg-Landau (GL) relaxation dynamics38,64,65. In 5d iridates, the strong SOI plays a unique role in competing with the electron correlation, giving rise to the strong locking of crystal lattice and magnetic moments10,66. In other words, the Ir magnetic moment strictly follows the rotation of IrO6 octahedral rotation10. By assuming an Ir–O bond length similar to that in the Sr2IrO4 single crystal11, the pseudo-tetragonal unit cell of the SL gives an octahedral rotation angle ~ 10°. A value φ = 10° was therefore adopted for the numerical simulation. In the simulation, we use a 64 × 64 square lattice with \(t = \frac{1}{{\cos\varphi }} \approx 1.02\), U = 3, Γ1 = Γ2 = 0.05, and three choices of magnetic field h = {(0, 0, 0), (0.1, 0, 0), (0, 0, 0.1)}. The GL dynamics with damping parameter α = 0.1 is integrated using the Heun-projected scheme67 with time-step ∆τ = 0.01. The molecular torques on mi are obtained by integrating out the electrons at each time step using the kernel polynomial method and gradient based probing38,68,69,70,71,72, with M = 500 Chebyshev moments and R = 128 random vectors.

After obtaining the equilibrium spin configurations, we use Kubo formula46 to evaluate the longitudinal conductivity, by diagonalizing Equation (4) exactly. A Lorentzian broadening factor η = 1/64 is used in the Kubo formula calculation. For each temperature, we average the longitudinal conductivity over 20 snapshots, separated by at least twice of the auto correlation time (For example, for h = (0, 0, 0), T = 0.102, the separation between two snapshots is 3 × 104 integration time steps).

The Mst in the main text is defined as

where N = 64 × 64 is the total number of lattice sites, and \({\tilde{\mathbf{s}}}_{\mathbf{Q}}\) is the Fourier transform of \({\tilde{\mathbf{s}}}_j\) defined in the main text.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gantmakher, V. F. & Gantmacher, F. R. Electrons and Disorder in Solids (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2005).

Giraldo-Gallo, P. et al. Scale-invariant magnetoresistance in a cuprate superconductor. Science 361, 479–481 (2018).

Mott, N. F. Metal–insulator Transitions (Taylor & Francis, 1990).

Dagotto, E. Correlated electrons in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 763–840 (1994).

Bertinshaw, J., Kim, Y. K., Khaliullin, G. & Kim, B. J. Square lattice iridates. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 315–336 (2019).

Rau, J. G., Lee, E. K.-H. & Kee, H.-Y. Spin–orbit physics giving rise to novel phases in correlated systems: iridates and related materials. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 7, 195–221 (2016).

Cao, G. & Schlottmann, P. The challenge of spin–orbit-tuned ground states in iridates: a key issues review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81, 042502 (2018).

Witczak-Krempa, W., Chen, G., Kim, Y. B. & Balents, L. Correlated quantum phenomena in the strong spin–orbit regime. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 57–82 (2014).

Kim, B. J. et al. Novel J eff = 1/2 Mott state induced by relativistic spin–orbit coupling in Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 076402 (2008).

Jackeli, G. & Khaliullin, G. Mott Insulators in the strong spin–orbit coupling limit: from heisenberg to a quantum compass and kitaev models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 017205 (2009).

Crawford, M. K. et al. Structural and magnetic studies of Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. B 49, 9198–9201 (1994).

Cao, G., Bolivar, J., McCall, S., Crow, J. E. & Guertin, R. P. Weak ferromagnetism, metal-to-nonmetal transition, and negative differential resistivity in single-crystal Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. B 57, R11039–R11042 (1998).

Manousakis, E. The spin-1/2 Heisenberg antiferromagnet on a square lattice and its application to the cuprous oxides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 63, 1–62 (1991).

Hsieh, D., Mahmood, F., Torchinsky, D. H., Cao, G. & Gedik, N. Observation of a metal-to-insulator transition with both Mott–Hubbard and Slater characteristics in Sr2IrO4 from time-resolved photocarrier dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 86, 035128 (2012).

Kim, J. et al. Large spin-wave energy gap in the bilayer iridate Sr3Ir2O7: evidence for enhanced dipolar interactions near the Mott metal–insulator transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 157402 (2012).

Moser, S. et al. The electronic structure of the high-symmetry perovskite iridate Ba2IrO4. New J. Phys. 16, 013008 (2014).

Zocco, D. A. et al. Persistent non-metallic behavior in Sr2IrO4 and Sr3Ir2O7 at high pressures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 255603 (2014).

Fujiyama, S. et al. Two-dimensional Heisenberg behavior of J eff = 1/2 Isospins in the paramagnetic state of the spin–orbital mott insulator Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 247212 (2012).

Chen, Q., Stajic, J., Tan, S. & Levin, K. BCS–BEC crossover: from high temperature superconductors to ultracold superfluids. Phys. Rep. 412, 1–88 (2005).

Randeria, M. & Taylor, E. Crossover from Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer to Bose–Einstein condensation and the unitary Fermi gas. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 209–232 (2014).

Slater, J. C. Magnetic effects and the Hartree–Fock equation. Phys. Rev. 82, 538–541 (1951).

Matsuno, J. et al. Engineering a spin-orbital magnetic insulator by tailoring superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 247209 (2015).

Hao, L. et al. Two-dimensional J eff = 1/2 antiferromagnetic insulator unraveled from interlayer exchange coupling in artificial perovskite iridate superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 027204 (2017).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Manipulation of electronic structure via alteration of local orbital environment in [(SrIrO3)m, (SrTiO3)] (m = 1, 2, and ∞) superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 94, 245113 (2016).

Groenendijk, D. J. et al. Spin–orbit semimetal SrIrO3 in the two-dimensional limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 256403 (2017).

Schütz, P. et al. Dimensionality-driven metal–insulator transition in spin–orbit-coupled SrIrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 256404 (2017).

Wang, F. & Senthil, T. Twisted Hubbard model for Sr2IrO4: magnetism and possible high temperature superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 136402 (2011).

Alexander, S., Helman, J. S. & Balberg, I. Critical behavior of the electrical resistivity in magnetic systems. Phys. Rev. B 13, 304–315 (1976).

Haas, C. Spin-disorder scattering and magnetoresistance of magnetic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 168, 531–538 (1968).

Bishop, A. R. & Roder, H. Theory of colossal magnetoresistance. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2, 244–251 (1997).

Ramirez, A. P. Colossal magnetoresistance. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 9, 8171–8199 (1997).

Bogdanov, N. A. et al. Orbital reconstruction in nonpolar tetravalent transition-metal oxide layers. Nat. Commun. 6, 7306 (2015).

Takayama, T., Matsumoto, A., Jackeli, G. & Takagi, H. Model analysis of magnetic susceptibility of Sr2IrO4: a two-dimensional J eff = 1/2 Heisenberg system with competing interlayer couplings. Phys. Rev. B 94, 224420 (2016).

Cao, G. et al. Anomalous magnetic and transport behavior in the magnetic insulator Sr3Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. B 66, 214412 (2002).

Brandow, B. H. Electronic structure of Mott insulators. Adv. Phys. 26, 651–808 (1977).

Schulz, H. J. Effective action for strongly correlated fermions from functional integrals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 2462–2465 (1990).

Mukherjee, A. et al. Testing the Monte Carlo—mean field approximation in the one-band Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 90, 205133 (2014).

Chern, G.-W., Barros, K., Wang, Z., Suwa, H. & Batista, C. D. Semiclassical dynamics of spin density waves. Phys. Rev. B 97, 035120 (2018).

Arita, R., Kuneš, J., Kozhevnikov, A. V., Eguiluz, A. G. & Imada, M. Ab initio studies on the interplay between spin–orbit interaction and coulomb correlation in Sr2IrO4 and Ba2IrO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 086403 (2012).

Watanabe, H., Shirakawa, T. & Yunoki, S. Microscopic study of a spin–orbit-induced mott insulator in Ir oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 216410 (2010).

Carter, J.-M., Shankar, V. V. & Kee, H.-Y. Theory of metal–insulator transition in the family of perovskite iridium oxides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035111 (2013).

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241–255 (1958).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91–98 (1960).

Shekhtman, L., Entin-Wohlman, O. & Aharony, A. Moriya’s anisotropic superexchange interaction, frustration, and Dzyaloshinsky’s weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 836–839 (1992).

Hao, L. et al. Giant magnetic response of a two-dimensional antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 14, 806–810 (2018).

Kubo, R. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. I. General theory and simple applications to magnetic and conduction problems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12, 570–586 (1957).

Seidel, J. et al. Conduction at domain walls in oxide multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 8, 229 (2009).

Choi, T. et al. Insulating interlocked ferroelectric and structural antiphase domain walls in multiferroic YMnO3. Nat. Mater. 9, 253 (2010).

Meyers, D. et al. Magnetism in iridate heterostructures leveraged by structural distortions. Sci. Rep. 9, 4263 (2019).

Ge, M. et al. Lattice-driven magnetoresistivity and metal-insulator transition in single-layered iridates. Phys. Rev. B 84, 100402(R) (2011).

Wang, C. et al. Anisotropic magnetoresistance in antiferromagnetic Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041034 (2014).

Lee, N. et al. Antiferromagnet-based spintronic functionality by controlling isospin domains in a layered perovskite iridate. Adv. Mater. 30, 1805564 (2018).

Lu, C. et al. Revealing controllable anisotropic magnetoresistance in spin–orbit coupled antiferromagnet Sr2IrO4. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1706589 (2018).

Baibich, M. N. et al. Giant magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472–2475 (1988).

Nakayama, H. et al. Spin Hall magnetoresistance induced by a nonequilibrium proximity effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 206601 (2013).

Hou, D. et al. Tunable sign change of spin hall magnetoresistance in Pt/NiO/YIG structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 147202 (2017).

Smit, J. Magnetoresistance of ferromagnetic metals and alloys at low temperatures. Physica 17, 612–627 (1951).

Pekker, D. & Varma, C. M. Amplitude/Higgs modes in condensed matter physics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 6, 269–297 (2015).

Wadley, P. et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 351, 587–590 (2016).

Fina, I. et al. Anisotropic magnetoresistance in an antiferromagnetic semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 5, 4671 (2014).

Thio, T. et al. Magnetoresistance and the spin-flop transition in single-crystal La2CuO4+y. Phys. Rev. B 41, 231–239 (1990).

Raičević, I., Popović, D., Panagopoulos, C. & Sasagawa, T. Large positive magnetoresistance of the lightly doped La2CuO4 Mott insulator. Phys. Rev. B 81, 235104 (2010).

Hiroi, Z., Yamaura, J., Hirose, T., Nagashima, I. & Okamoto, H. Lifshitz metal–insulator transition induced by the all-in/all-out magnetic order in the pyrochlore oxide Cd2Os2O7. APL Mater. 3, 041501 (2015).

Hohenberg, P. C. & Halperin, B. I. Theory of dynamic critical phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 49, 435–479 (1977).

Bray, A. J. Theory of phase-ordering kinetics. Adv. Phys. 43, 357–459 (1994).

Cao, G. et al. Electrical control of structural and physical properties via strong spin-orbit interactions in Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 017201 (2018).

Mentink, J. H., Tretyakov, M. V., Fasolino, A., Katsnelson, M. I. & Rasing, T. Stable and fast semi-implicit integration of the stochastic Landau–Lifshitz equation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 176001 (2010).

Weiße, A., Wellein, G., Alvermann, A. & Fehske, H. The kernel polynomial method. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 275–306 (2006).

Barros, K. & Kato, Y. Efficient Langevin simulation of coupled classical fields and fermions. Phys. Rev. B 88, 235101 (2013).

Barros, K., Venderbos, J. W. F., Chern, G.-W. & Batista, C. D. Exotic magnetic orderings in the kagome Kondo-lattice model. Phys. Rev. B 90, 245119 (2014).

Wang, Z., Barros, K., Chern, G.-W., Maslov, D. L. & Batista, C. D. Resistivity minimum in highly frustrated itinerant magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 206601 (2016).

Wang, Z., Chern, G.-W., Batista, C. D. & Barros, K. Gradient-based stochastic estimation of the density matrix. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 094107 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge experimental assistance and discussion with H. D. Zhou, H. X. Xu, H. Suwa, Eun Sang Choi, C. Rouleau, Z. Gai, J. K. Keum, and N. Traynor. J.L. acknowledges the support by the start-up fund and the Science Alliance Joint Directed Research & Development Program at the University of Tennessee, the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DMR-1848269, and the DOD-DARPA under Grant No. HR0011-16-1-0005. J.L. and C.D.B. acknowledge the support by the Organized Research Unit Program at the University of Tennessee. Z.W. and C.D.B. are supported by funding from the Lincoln Chair of Excellence in Physics. M.P.M.D. and D.M. are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Early Career Award Program under Award Number 1047478. J.S. and J.-H.C. are supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Young Investigator Program under Grant FA9550-17-1-0217. K.B. is supported by the LDRD program at Los Alamos National Laboratory. A portion of the work was conducted at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. DOE, OS by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work used resources of the Compute and Data Environment for Science (CADES) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725. This research used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. conceived and directed the study. L.H., J.Y. and D.M. undertook sample growth and characterization. L.H., J.Y., D.M., J.W.K. and P.J.R. performed magnetic scattering measurements. L.H., J.Y., G.F., Y.S.C. and D.H. conducted XMCD measurements. L.H., J.Y., J.S. and J.H.C performed transport measurements. L.H. and J.L. analyzed data. Z.W., K.B. and C.D.B. performed the numerical simulations. L.H., Z.W., M.P.M.D., C.D.B. and J.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Arun Paramekanti, Dazhi Hou, Jianshi Zhou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, L., Wang, Z., Yang, J. et al. Anomalous magnetoresistance due to longitudinal spin fluctuations in a Jeff = 1/2 Mott semiconductor. Nat Commun 10, 5301 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13271-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13271-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.