Abstract

Atom-thin transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have emerged as fascinating materials and key structures for electrocatalysis. So far, their edges, dopant heteroatoms and defects have been intensively explored as active sites for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) to split water. However, grain boundaries (GBs), a key type of defects in TMDs, have been overlooked due to their low density and large structural variations. Here, we demonstrate the synthesis of wafer-size atom-thin TMD films with an ultra-high-density of GBs, up to ~1012 cm−2. We propose a climb and drive 0D/2D interaction to explain the underlying growth mechanism. The electrocatalytic activity of the nanograin film is comprehensively examined by micro-electrochemical measurements, showing an excellent hydrogen-evolution performance (onset potential: −25 mV and Tafel slope: 54 mV dec−1), thus indicating an intrinsically high activation of the TMD GBs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Grain boundaries (GBs) are commonly found in atom-thin or so called two-dimensional (2D) polycrystalline materials1,2,3, where they can be described as line defects. They play a key role in shaping the properties and performance of 2D materials in applications as varied as mechanical strengthening4, photovoltaics5,6, electronics7,8,9, and catalysis10,11. Engineering the structure and/or the density of GBs in 2D materials could thus become a promising way to tailor their performance. One particular class of 2D materials, transitional metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have attracted a great deal of attention for its possible uses in electrocatalytic reactions12,13, including the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER)14,15. Due to the low cost, earth abundance and good stability of a wide range of TMDs, substantial work has thus been undertaken to improve their electrocatalytic activity12,13 by, e.g., exposing their edges16,17,18,19, doping with heteroatoms20, and/or creating and straining structural defects11,15,19,21,22. In contrast, less attention has been paid to the role of GBs due to their typically low number density and large structural variations, even though GBs have been predicted to be highly electrocatalytically active23. The poor control over the density and structure of GBs stems from the fast gaseous kinetic processes and the multiplicity of chemical phases involved during the growth of TMDs2,24,25. To date, the most common methods employed to synthesize atomically thin polycrystalline TMDs include chemical vapor deposition (CVD)2,3,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, physical vapor deposition (PVD)37,38,39, and metal organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD)40,41. Films grown using these techniques usually exhibit grain sizes ranging from hundreds of nanometers to several millimeters, resulting in a low GB density, as summarized in Fig. 1a (See the statistical method in Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Overview of the grain size and density in TMD materials obtained by various fabrication methods, such as CVD2,3,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, MOCVD40,41, PVD37,38,39, top–down syntheses of sulfurization/selenization of metal and metal oxide thin films73,74,75,76,77, and thermal decomposition of thiosalts thin films78. Although small grains (~20 nm in diameter) were observed in TMDs synthesized by the top–down methods of sulfurizing Mo-based thin films73,74, or thermal-decomposition of Mo-thiosalts thin films78, the grain density in the film is not very high owing to their interlayer diffusion synthesis mechanism. b Schematic of the wafer-scale growth of TMD nanograin films. Ultra-high-density Au quantum dots (QDs) were used to grow the MoS2 (as well as WS2 atom-thin films: see Supplementary Information). c TMD nanograin film from wafer scale to nanoscale, including photograph (i), optical image (ii), SEM image (iii), and HRTEM image (iv). d False-colored SEM image of the Au QDs on a SiO2/Si substrate, showing an average diameter of 4.8 nm. e Statistical distributions of Au QDs obtained from Au films with different deposition times. The evaporation rate is ~0.1 Å s−1 in our experiments. f Raman spectra acquired from the MoS2 film. The difference (∆ ~20 cm−1) between the out-of-plane (A1g) and in-plane (E12g) Raman modes indicates that the MoS2 film is 1–3 layers (1–3 L)2,44. Compared to CVD-grown and exfoliated samples, the reduced intensity of the in-plane mode indicates a highly polycrystalline structure for this MoS2 film.

Here, we fabricate wafer-size atomically thin TMD films with sub-10 nm grains by means of Au-quantum-dots (QDs)-assisted vapor-phase growth, demonstrating an ultra-high-density of GBs (up to ~1012 cm−2). The quality of the films was examined by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Raman spectroscopy. Experimental evidence as well as phase-field simulations demonstrate that the Au QDs regulate the formation of the TMD grains. We then investigated the catalytic activity of these nanograin films by a four-electrode micro-electrochemical cell for hydrogen evolution. An excellent performance (−25 mV and 54 mV dec−1 for the onset potential and the Tafel slope) was obtained for our MoS2 nanograin films, indicating a good intrinsic activation of the GB-rich 2D basal plane.

Results

Controlled growth of the TMD nanograin film

The main obstacles that hinder the vapor growth of TMDs at the 2D limit to grain sizes typically <10 nm consist of the precise control of the nucleation sites and the growing rate of the grains. These can be addressed by using a high-density of Au QD seeds and a low mass flow rate of the vapor sources. Figure 1b illustrates the wafer-scale growth process (see also a full description of the growth setup in Supplementary Fig. 2). A wafer-scale Au QD layer was fabricated on 2-inch sapphire or SiO2/Si substrates and used to subsequently grow the atom-thin MoS2 films. Figure 1c shows the geometries of the as-grown wafer-size film from the centimeter to the nanometer scale. The SEM image (Fig. 1d) shows the as-prepared Au QDs with an ultra-high density up to ~2 × 1012 cm−2 and average diameter down to ~4.8 nm, which was achieved by heating a thin Au film on sapphire or SiO2/Si substrates at a high temperature. We attribute the formation process of these Au QDs to a solid-state dewetting behavior at the interface between the SiO2 (or Al2O3) and Au42,43 (Supplementary Fig. 3). The initial deposition time of the Au films prior to heating determines the density and the size of the final Au QD structures: a shorter deposition time results generally in a smaller size and a higher density of Au QDs, as shown in Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 4. The MoS2 film is then grown using a vapor-phase growth technique (see further experimental details in Method section), after which Au QDs can be removed from as-grown films, by using KI/I2 etchant at room temperature. The successful removal of the Au QDs after the etching treatment was assessed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and STEM imaging in Supplementary Figs. 5–7, showing only minimal amounts of residual Au present. The resulting MoS2 films were examined by Raman spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 1f. The Raman spectroscopy measurements indicate that the MoS2 film is 1–3 layers thick (1–3 L). A weak in-plane mode (E2g1 at 385 cm−1) was observed in our 1–3 L film, with an intensity ratio with the out-of-plane mode A1g (at 405 cm−1), \(I_{E_{2g}^1}/I_{A_{1g}}\) (~0.28), significantly smaller than the ratios typically measured on the CVD-grown (~1.89) and exfoliated (~1.57) MoS2 films in our experiment, suggesting a highly polycrystalline structure in this film (see the details in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 1).

Au QDs regulate the formation of TMD grains in two ways. The first way is that Au QDs can facilitate the TMD nucleation at the initial stage of the TMD growth. The melting temperature of Au will dramatically decrease as its size decreases to several nanometers, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. As a result, at the growth temperature of TMDs (650–800 °C), Au QDs tend to be in the liquid phase due to their small size. Such liquid Au droplets can facilitate the formation of the TMD nucleation sites during the growth process. The second way is that the Au QDs can confine the size of the TMD domains below 10 nm. Our deposition method can produce well-dispersed Au QDs with a very high number density, with average spacing between QDs down to a few nanometers. As a result, the formation of the TMD grains will be constrained at this length scale.

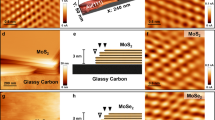

Atomic structure of the TMD nanograin films

We investigated the atomic structure of the TMD nanograin films using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 2a shows an overview TEM image of a uniform and continuous MoS2 film suspended on a Cu-supported lacey carbon TEM grid. This region is representative of the tens of samples examined, and the MoS2 film comprises polycrystalline patches with regions of 1–3 L MoS2 (consistent with the measured Raman frequencies44). To evaluate the grain distribution, we randomly chose six regions of the film, labeled 1–6 on Fig. 2a, for further HRTEM imaging. The original HRTEM images from these six regions, corresponding Fourier transforms (FFTs) and frequency filtered images (IFFTs)45 are shown in the top (a1–a6), middle (b1–b6), and bottom panels (c1–c6) of Fig. 2a, respectively. To aid the visualization of the different grains, black-dashed lines are added along the edges of the grains in the bottom panel (c1–c6). From these images, we can identify 8–10 distinct MoS2 grains in a ~700 nm2 region, suggesting an ultra-high grain density (up to ~1012 cm−2 in this representative patch, consistent with the initial estimate derived from the Au QD number density) in our sample. Accordingly, the average diameter of the grains is <10 nm, with some observed grains smaller than 5 nm in diameter. To our knowledge, this is the smallest grain size obtained to date in materials at the 2D limit17,46,47.

a TEM image of the 1–3 L MoS2 nanograin film, showing a uniform and continuous atom-thin layer with Au nanoparticles (dark spots). Top panel (a1–a6): HRTEM images from regions 1–6. Middle panel (b1–b6): Fourier transforms (FFTs) of regions 1–6 from the corresponding TEM image. Bottom panel (c1–c6): false-colored frequency filtered (IFFTs) images of the same regions. Grains with different orientations give rise to distinct sets of rotated spot patterns in the FFTs, as indicated by colored circles in the middle panel (b1–b6); in turn, the localization of the grains can be visualized in real space by color coding the corresponding contribution to the IFFT of a given set of diffraction spots, and overlaying the IFFTs into a composite colored image (in bilayer regions, the colors are combined). In order to better visualize the different grains, the grains are highlighted in the IFFT images with black-dashed lines. b HAADF STEM investigation of MoS2 grains. Left: HAADF STEM image showing the GBs between three MoS2 grains. Inset on the left figure: Fourier transform of the image showing three distinct sets of MoS2 diffraction patterns with rotation angles of 11.6° and 25.6°. Middle: composite color-coded IFFT image. Right: dilatation map of b after applying GPA routine to the monolayer MoS2. c Higher magnification atomic resolution HAADF STEM image of the brown-dashed line marked region in b, showing the detailed atomic structure of the GB, which is composed of 5|7 and 4|8 rings. Mo atoms are marked with indigo dotted circles and S atoms marked with yellow dotted circles. d Grain size dependence on Au nanoparticle size (average diameter) in the MoS2 nanograin film. The error bars of Au nanoparticles are extracted from the full-width at half maximum in Fig. 1e.

We then employed atomic-resolution high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging in the STEM to examine the atomic structure of the GBs on the as-grown nanograin films, representative examples of which are shown in Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 9. The inspection of dozens of boundary locations systematically found that nanograins in our films are stitched by GBs. The atomic structure of the GBs varied significantly (great care was taken to exclude any structure modification arising from beam damage, see Experimental section for details). Structures comprising a combination of 5|7 and 6|8 rings were however dominant in our nanograin films and are illustrated in Fig. 2c. A small number of 8|4|4 structures were found, but in contrast, 12|4 rings were never observed in “pristine” GBs (i.e., before any substantial exposure to the electron beam). Their atomic structures in MoS2 are schematically illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Although the nature of atomic-resolution microscopy precludes large-scale statistical studies, we investigated as many different regions in a MoS2 nanograin film as practically possible. Six further regions over a large range were carefully examined with atomically resolved HAADF–STEM imaging (Supplementary Fig. 11), and 3 to 5 GBs can be observed in a 400 nm2 area, confirming the ultra-high-density of GBs observed in STEM (consistent with the ~1012 cm−2 suggested by the Au QD density). Moreover, tens of samples with different sizes of Au QDs were grown: the grain size measured in the resulting MoS2 films exhibits a clear linear relationship with the QD size, as shown in Fig. 2d. This provides a strong proof that the TMD grain size can be carefully controlled by the Au QD substrate. Remarkably, our method can be also extended to other TMD materials such as WS2 (Supplementary Fig. 12 summarizes similar results to those described above, using WS2 instead of MoS2), making it as a universal approach for the wafer-size synthesis of atom-thin films with sub-10 nm grains.

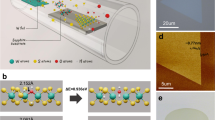

Growth mechanism of the TMD nanograin film

A climb and drive zero-dimensional (0D)/2D interaction is proposed to explain the Au QDs-assisted-growth mechanism of the TMD nanograins at the atomic limit, which is supported by real-time phase-field simulations and experimental evidence. The phase-field simulation of the climb process shows that, once the Au QDs encounter a MoS2 edge at the growth front, they migrate swiftly from the SiO2 surface onto the MoS2 surface (Fig. 3a). This behavior is mainly attributed to a smaller wetting angle of the Au QDs droplet (Au is in the liquid phase at the growth temperature) on MoS2 than that on the SiO2 substrate48 (Supplementary Fig. 13). This phenomenon is also experimentally confirmed by cross-sectional TEM, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 14, where nearly all the Au QDs sit on the surface of the MoS2. Subsequently, the phase-field simulation suggests the formation of a second MoS2 layer will drive the Au QD droplets along its growth direction (Fig. 3b). A number of the Au QDs may thus coalesce and form bigger droplets during the driving process. This is supported by our experimental evidence: the size of the Au QDs on the MoS2 is usually larger than those on SiO2, and some of them sit at the edge of the MoS2 sheet, as illustrated in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 15a–b. This drive process will be immobilized when the Au QDs reach a critical size (as a result of the Au returning to the solid phase). This would be consistent with experimental observations that larger Au particles seen in the minority multilayer regions of the nanograin film appear to be encapsulated by the MoS2 film, suggesting they were immobilized after reaching a critical size, leading the MoS2 to grow over them rather than driving them forward (see Supplementary Figs. 15c, d and 16).

a Schematic of the climb stage: the Au QDs droplets tend to climb onto the MoS2 monolayer from the SiO2 substrate due to the surface tension difference. b Schematic of the drive stage: the growth of a second MoS2 layer tends to push the Au QDs along the growth direction. Most of the Au QDs will be stabilized at the grain boundaries in order to minimize their surface energy. c SEM image showing the distribution of the Au QDs on the edges of growing MoS2 layers (marked by the red-dashed line). Au QDs are usually larger on the MoS2 layers (indicated by blue arrows) than those observed on the SiO2 substrate. d Real-time phase-field simulation showing the formation of the MoS2 nanograin film. The Au QDs numbered 1–4 show that the growth of the MoS2 layer will push Au QDs toward the grain boundaries. Au QDs numbered 5–6 show a zipper effect to suture the neighboring grains together. The movie can be found in Supplementary Movie 1 (Real-time phase-field simulation of the growth process).

Figure 3d shows successive snapshots that illustrate the growth of TMD nanograins films via a phase-field simulation (also see Supplementary Movie 1). The Au QDs serve as nucleation sites to form the first MoS2 layer (Fig. 3d–i). The growth of a second MoS2 layer will then drive the Au QDs. Some of the Au QDs will be immobilized at the GBs (Fig. 3d ii and iii, number 1–4). More interestingly, we found that neighboring grains could be sutured together through a zipper effect (Fig. 3d iii-v, number 5 and 6, see Method and Supplementary Fig. 17). It is important to emphasize that the growth model for the TMD nanograin films we describe here is driven by a 0D/2D interaction at the atomic limit, which is distinct from the conventional metal-film-assisted growth of 2D materials (2D/2D)29,35, or from the metal-nanoparticle-assisted growth of nanowires (0D/1D)49.

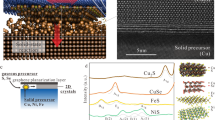

Hydrogen production of the TMD nanograin films

We first performed first-principle calculations50 to examine all of the HER catalytic active sites in model MoS2 geometries (Fig. 4a), including the basal plane sites, edges with different passivation (Mo or S)51, and GBs with different atomic structural configurations (5|7, 6|8, 4|6, 12|4, and 8|4|4 rings). The calculated hydrogen adsorption free energies (∆GH)52 of various atomic structures (Supplementary Fig. 18) are shown in Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 2. The MoS2 basal plane has a ∆GH as high as 1.79 eV15, indicating a HER-inert surface. For edges and GBs, we compare the activities of most of the experimentally observed structures, e.g., 5|7 (0.132 eV), 6|8 (−0.237 eV), and 8|4|4 (0.52 eV, −0.044 for defect) ring combinations,2,53 50% S passivated Mo edge (0.561 eV), and 50% passivated S edge (0.446 eV)53,54. It can be seen that GBs indeed show comparable or even better activity than the edges in general, suggesting GBs are promising candidates as high-efficient catalyst sites. In addition, we note that some edges are not further considered here owing to their instability in air; for instance, the otherwise energetically favorable Mo edge without passivation of S atoms (−0.446 eV).

a Schematic of MoS2 with an illustration of the main types of catalytically active sites for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) including: basal plane atomic sites, edges, and GBs. b corresponding ∆GH of various types of catalytically active sites in MoS2 catalysts. Some types of GBs (e.g., 844, 6–8, and 5–7) show better electrocatalytic activity than edges.

We then developed a micro-electrochemical cell to investigate the HER activity of our sub-10 nm nanograin films. Furthermore, the HER activity of model single-GBs (mirror GB)3,11, single-edge (Supplementary Fig. 19)53, and basal plane structures in MoS2 samples from CVD method1 were also examined for comparison. Figure 5a illustrates the micro-cell’s structure. Figure 5b shows a picture of the micro-cell and electrodes configuration where a graphite counter electrode and a micro-reference electrode were used. In our experiment, a vertical MoS2/graphene heterostructure was designed, in which graphene played two important roles: one is to efficiently inject electrons to MoS2. Such a strategy has already been widely adopted in TMD-based semiconductor devices55,56, while the other is to provide a fair comparison by eliminating the contact resistance variations of the individual MoS2 electrodes onto the substrate. Previous work56,57 suggested the formation of an inconsistent contact barrier between the MoS2 and the Au electrode, owing to their complex metal–semiconductor interface leading to effects such as Fermi pinning, creation of alloy structures, etc. The formation of such a contact barrier was also studied by phase engineering21 and field-effect gating58 in the HER process. Considering the important role of this graphene supporting layer, we introduced one more working electrode in the micro-electrochemical cell (four-electrode micro-electrochemical cell59,60, see circuit diagram in Supplementary Fig. 20) to monitor in situ its conductance. The device fabrication of the MoS2/graphene heterostructure is detailed in Supplementary Figs. 21 and 22, and Supplementary Notes 2 and 3. The heterostructure was also characterized by Raman spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 23). Figure 5c–f shows the optical images obtained from the typical devices fabricated with a MoS2 nanograin film, a single-GB model structure (the presence of a GB was confirmed by Raman mapping, as illustrated on Fig. 5d, right panel), a single edge, and a basal plane, respectively. In these optical images, only the exposed MoS2 in the reaction window contributes to the electrocatalytic reaction, as indicated by the white arrows. The rest of the areas are covered by poly(methylmethacrylate) (PMMA), and the graphene supporting layer (Supplementary Fig. 24) are also electrochemically inert.

a Schematic of the micro-electrochemical cell for HER measurements, where graphene serves as a vertical electron injector. b Photograph of the micro-electrochemical cell. c Optical images of the MoS2 nanograin device, consisting of a PMMA reaction window, a MoS2 nanograin film, a graphene supporting layer, and a SiO2/Si substrate from top to bottom. d–f Optical images of the MoS2 devices with a single GB (d), a single edge (e), and basal plane (f), respectively. In these devices, the HER process occurs at the exposed widows on the PMMA passivation film as indicated by the white arrow. g, h Polarization curves of the current density (g) and the corresponding Tafel plots (h) of the MoS2 devices. The window size is ~80 μm2 for each device.

Figure 5g, h shows the polarization curves and the corresponding Tafel slopes in a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution and provide several interesting observations. First, the resistivity of the graphene supporting layer is found to be as low as 10−4 Ω mm during the HER (see the inset in Fig. 5g), indicating the excellent current injection performance of the graphene layer. Secondly, the single-GB device delivers a better activity than the single-edge device (see also the measurement of the active length per unit area of the GB in Supplementary Fig. 25), and both are superior to the basal plane device, echoing our theoretical calculation results shown above. More importantly, our MoS2 nanograin film shows a remarkable HER performance: −25 mV and 54 mV dec−1 for the onset potential and the Tafel slope, respectively.

In order to evaluate the HER performance of the TMD nanograin film accurately, we have fabricated hundreds of devices and tested them in a size-controlled micro-electrochemical cell. The HER data, including current density, Tafel slope, and onset potential of the nanograin film and other types of electrostatically active sites are presented in Fig. 6a–c and Supplementary Fig. 26. The window size is controlled from 25 to 150 μm2. Our results demonstrate the excellent HER performance of the nanograin film. The HER current density of the nanograin film is up to ~1000 mA cm−2 while the Tafel slope and onset potential are down to ~50 mV dec−1 and ~−25 mV, thus exhibiting a performance superior to devices using the basal plane of the CVD film, the single edge and the single GB. This suggests that sites on the otherwise HER-inert basal plane of the MoS2 have been activated by the presence of GBs. The obtained HER performance is also comparable to the performance of strained sulfur vacancies15 or the metastable 1T-phase61, which are arguably more challenging to realize experimentally.

Finally, as a comparison, we have conducted conventional macro-cell measurements on a MoS2 nanograin film on a glassy carbon electrode, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 27–32 and Supplementary Notes 4 and 5. A remarkable HER performance (−44 mV and 55 mV dec−1 for the onset potential and the Tafel slope, respectively) of the MoS2 nanograin film is observed (Supplementary Fig. 28), which is consistent with the results obtained in the micro-cell. It also shows an excellent long-term stability for HER, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 29. It is worth mentioning that Au single-atom exists in our MoS2 nanograin film and may contribute to the overall HER performance. However, based on the structure (Supplementary Fig. 6) and extremely low content (Supplementary Fig. 7) of Au single atoms as well as their low HER-activity (Supplementary Figs. 33 and 34, and Supplementary Note 6), we conclude that the residual Au is not the main contributor of the good HER activity in MoS2 nanograin film. The measured performance should be mainly from GB due to its superior activity and ultra-high density. As a proof-of-concept practical application, hydrogen production on a wafer-size (2 inch) MoS2 nanograin film was also demonstrated (see Supplementary Movie 2). A large amount of H2 bubbles could be produced during the reaction, demonstrating the tantalizing potential for practical application of GBs-engineered catalysts for hydrogen production.

Discussion

In summary, we have engineered wafer-size ultra-high-density GBs at the 2D limit in TMD films. Phase-field simulations reveal a climb and drive 0D/2D-interaction-based growth mechanism. As a proof-of-concept application in electrocatalysis, devices based on our TMD nanograin films deliver a superior hydrogen evolution performance (onset potential: −25 mV and Tafel slope: 54 mV dec−1), indicating an intrinsic activation of the GB-rich 2D plane. Beyond electrocatalysis, the nanograin films may provide further diverse potential applications, such as in resistance-memory devices, flexible devices, or for use as mechanical films and molecular sieving films.

Methods

Growth of water-size MoS2 and WS2 nanograin films

The first step consists in depositing Au layers of various thicknesses on clean 2-inch sapphire or SiO2/Si wafers by e-beam evaporation at the rate of 0.1 Å s−1; these are used as the growth substrate for the nanograin films. Subsequently, Au-coated wafers are introduced into a CVD apparatus, which is depicted in detail in Supplementary Fig. 2. MoO3 or WO3 powders were loaded in an aluminum oxide boat and used as sources. Sulfur powder is placed in a second aluminum oxide boat upstream of the MoO3 or WO3 in the outer tube. In a third step, Ar (flow 100 sccm) and Ar/water vapor (flow 50 sccm) are introduced as carrier gases for the growth in the inner and outer tubes, respectively. The growth temperature was kept at 780 °C in low-vacuum conditions of 1–10 kPa; the S powder is separately kept at ~160 °C. Adjusting the growth time is used to control the thickness of films. For example, Condition (I): 3–5 min of the growth time for 1–3 layers (1–3L); Condition (II): 5–10 min of the growth time for 4–5 layers (4-5 L). The growth parameters for WS2 nanograin films are similar to those used for MoS2, except for a higher growth temperature (900 °C). Finally, Au nanoparticles can be completely removed from as-grown nanograin MoS2 or WS2 films by using a KI/I2 etcher for 40–60 min at room temperature (see Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6).

Special care needs to be taken on two important points: (i) the Au QDs will form once the temperature is above 300 °C, due to the solid-state dewetting behavior42,43,62 at the interface of SiO2 (Al2O3) and Au (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Prior to the TMD growth, the substrate therefore stabilizes at this temperature to ensure the presence of Au QDs. (ii) Small amounts of water vapor are used to prevent the Mo or W sources from complete sulfurization before they reach the growth wafer, thus enabling a steady supply of sources during growth.

Theoretical calculations of ∆GH

The structural optimizations were carried out by adopting the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional, along with projector-augmented wave (PAW) potentials. The electronic wave functions were expanded in a plane wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 300 eV. For the Brillouin zone integration, 1 × 5 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point meshes were used. The energy convergence criterion for the electronic wavefunction was set at 10−5 eV. A vacuum distance of about 10 Å, both laterally between MoS2 ribbons and vertically between layers, was chosen when constructing the supercell to minimize possible spurious interaction between ribbons due to the periodic boundary conditions.

The hydrogen adsorption energy is defined as:

where \(E_{({\mathrm{MoS}_{2}} + {\mathrm{H}})}\) is the energy of the MoS2 system with a H atom adsorbed, \(E_{({\mathrm{MoS}_{2}})}\) is that of the MoS2 system without adsorbed H, and \(E_{({\mathrm{H}_{2}})}\) is that of gas phase H2 molecule.

The hydrogen adsorption free energy \(\Delta G_{\mathrm{H}}\) was defined as:

where ΔEH is the hydrogen adsorption energy, ΔEZPE is the zero-point energy difference, T is the temperature, and ΔSH is the entropy difference for hydrogen between the adsorbed state and the gas phase. The entropy of hydrogen adsorption is calculated as \(\Delta S_{\mathrm{H}} = 1/2S_{{\mathrm{H}_{2}}}\), where \(S_{{\mathrm{H}_{2}}}\) is the entropy of hydrogen molecule in the gas phase at standard conditions. We have calculated the vibrational frequencies of H adsorbed on different MoS2 systems, using finite differences to determine the Hessian matrix. According to the Sabatier principle, a good catalyst should bind a key intermediate in a manner that it is strong enough to allow the reagent H atoms to stay on the MoS2 system for reaction but weak enough to enable the release of any produced H2 molecules.

Phase-field simulations: simulation of the drive mechanism: MoS2 pushing Au QDs long the growth direction

The equilibrium status of the Au QDs at atomic steps dictates they can be pushed by the MoS2 growth front or not, which is crucial to dynamic evolution process. We undertook a case study of the equilibrium status of a Au QD at the edge of a MoS2 grain.

We adopt a phase-field model63 to simulate how the wetting process influences the equilibrium shape profile. The free energy function is given as,

where ρ is the phase field for the density of the liquid, V is the space volume, C = 10 and κ = 1 are constants of bulk energy and surface tension, respectively. ρ = 1 denotes the liquid phase and ρ = 0 denotes the vapor phase. The term \(\lambda \xi (\frac{{\rho ^3}}{3} - \frac{{\rho ^2}}{2})\) provides the driving force to the Au particle evolution with a coupling constant λ = 180, the dimensionless supersaturation ξ is set as (v0–vt)/vvapor, where v0 is the initial volume of the particle, vt is the real time volume of the particle, and vvapor is the volume of vapor. The evolution equation in the Allen–Cahn form is,

This evolution equation differs from that of Borcia et al.’s work63, which considers full fluid dynamics by including extra terms from the Navier–Stokes equation. In our study, we focus on the equilibrium and do not need to consider the exact evolution kinetics, thus leading to a simpler form of the evolution equation.

We control the contact angle between the Au QD and the substrate by fixing ρ = ρS at the substrate. Then, the contact angle can be analytically obtained via the equation \(\cos \theta = - 1 + 6\rho _{\mathrm{S}}^2 - 4\rho _{\mathrm{S}}^3\). We set ρS = 0.5 for the MoS2 substrate as corresponding to a contact angle between the Au and the substrate of 90°. Likewise, we set ρS = 0.21 for the MoS2 substrate as corresponding to a contact angle between the Au and the substrate of 138°.

We solve the evolution equation in Matlab by discretization with a time step of 0.01 and let the simulation run for a long enough time to ensure the system reaches equilibrium. The particle has a diameter of ~11 nm if resting on the MoS2 sheet.

The result shows that this Au QD will stay on the lower part of the MoS2 atomic step, but keeps in contact with the step edge. This suggests that if in the liquid phase, the Au QD would be pushed forward by the growth front of the second MoS2 layer during the growth.

Phase-field simulations: simulation of the zipper effect suturing the neighbor nanograins

If the Au QDs can be pushed by the growing MoS2 grains, they are likely to coalesce when two growth fronts meet, resulting in a complicated evolution. To obtain insights into this process, we perform another phase-field simulation. The phase-field model for the grain evolution and the set of parameters is almost identical to that reported in the literature for a similar system64. We ignore the evolution of the supersaturation and keep it at a constant of 0.1 everywhere. A detailed formulation is omitted here for brevity and can be found in other work65,66. In addition to the grains, we pay attention to the evolutions of the Au QDs. These QDs are modeled as hemispherical balls sliding on the substrate. For simplicity, we ignore the effect of the Au QDs on the growth of MoS2 grains. Then these QDs move on the substrate at a speed of v = 50 tan−1(t)/π, where t is the dimensionless time of evolution. When two QDs meet, they merge and form a larger QD. The volume of the new QD is the sum of the volumes of the previous two QDs and its center is at the midpoint between the centers of the previous two QDs. We then solve the evolution equation in Matlab by discretization with a time step of 0.01. Initially Au QDs are randomly placed on the substrate and there is in the vicinity of these QDs, a circular nucleus of MoS2 with a radius of r0 and a randomly assigned grain orientation.

To make the simulation consistent with the experiment, we extract some parameters from the experimental data. The experiment shows that the QDs are typically 4–5 nm. It also shows that when observed on top of the MoS2 sheet, the Au QDs are larger and less dense by around 2.5 times. This suggests by pushing Au QDs on top of MoS2 sheet, the final number of QDs will be 2/5 of the initial QDs. A subtle issue involved in the simulation is the ratio between nAu (initial number of Au QDs) and nn (the number of nuclei). To address this issue, we take a simulation case study to find a reasonable ratio. By fixing nn = 5, we obtain that when nAu = 9.2, the final number of QDs is 2/5 of the initial QD number, consistent with the experiments. We therefore choose nAu = 10 in further simulations.

Device fabrication procedure

First, large scale and high-quality single-layer graphene films were grown on Cu foils by CVD, and then transferred onto the prepatterned chips through a standard PMMA-assisted transfer method. Second, electron beam lithography (EBL) and O2 plasma were employed to pattern the graphene film into isolated strips with desired size, shape, and location. Third, as-grown MoS2 films were transferred on the patterned graphene strips, also using a PMMA-assisted transfer method. For the nanograin films, an additional step carefully positioning an EBL-defined PMMA template was needed. Fourth, an annealing process at 200 °C under high vacuum condition (1 × 10−5 Torr) was conducted to remove trapped residual molecules between the graphene and MoS2 films to optimize their interfaces. Fifth, EBL followed by thermal evaporation was employed to fabricate the electrodes (Cr/Au, 2 nm/60 nm) on graphene to connect the device with the Au contact pads. Finally, the entire device as fabricated on the chip was passivated by a 500 nm PMMA film, followed by EBL to remove the PMMA above the region of interest in the MoS2 film, and expose this section and this section only of the active catalyst to the electrolyte in HER test. Any electrochemical activity only occurs within the exposed window on the nanosheet, while the rest of regions, including the electrodes and the contact pads, are fully passivated by the PMMA to ensure a full electrochemical inertness.

A mirror GB in CVD-grown MoS2 is chosen as representative of single GBs, due to the ease with which it can be distinguished in optical images. It also consists mainly of 8|4|4 or defect 8|4|4 rings3,11 and has therefore a similar atomic structure to many of the complex boundaries observed in the nanograin films. The length–width ratio of the exposed window for the single-GB device or for the edge device (exposing the edge of an otherwise single-crystalline patch of CVD-grown MoS2) is fixed at a ratio of about 2:1, and the length of the window is comparable to the length of the edge or GB in experiments.

Four-electrode micro-electrochemical measurements

A micro-electrochemical cell with four electrodes (the circuit diagram for this cell is introduced in Supplementary Fig. 20) was developed in our experiment. Among the four electrodes, two serve as counter and reference electrode, using pencil graphite and a Ag/AgCl micro reference electrode (Harvard Apparatus), respectively. The remaining two electrodes were connected to the graphene supporting layer to monitor the conductance signal of graphene and the electrocatalytic signal of MoS2 during HER. The device fabrication procedure is shown in Supplementary Figs. 21 and 22, and Supplementary Notes 2 and 3. In all experiments, only the exposed region of the MoS2 nanosheets contributes to the recorded HER performance.

The typical four-electrode micro-electrochemical measurements were conducted in a 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte solution. The scan rate is 5 mV step−1. Both electrocatalytic current (Ic) and conductance current (Ids) are simultaneously detected. The leakage current in Ic is about 10−10 A (the electrochemical signal without any exposed window, i.e., from a region with PMMA passivation). The electrochemical current density is calculated by normalizing the current to the area of the exposed window on the MoS2. In 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, we measured:

Standard macro-electrochemical measurements

The macro-electrochemical measurements were conducted on a glassy carbon electrode (3 mm in diameter). Using a similar PMMA-assisted transfer method as described above, we transferred CVD-grown graphene and MoS2 nanograin films layer-by-layer on a glassy carbon electrode, and the sample area exceeding to glassy carbon electrode was scraped off before measuments. A standard three electrode system was used, and a Pt plate and Ag/AgCl rod served as counter and reference electrode, respectively. The measurement was performed on a biological electrochemical station in H2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was conducted at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. The onset potential is defined as the beginning potential of Tafel linear region. The stability test was carried out by taking continuous potential cycling in the potential window of −0.181 to ~0.219 V (versus RHE) at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. The presented LSV curves in macro-electrochemical cell were iR-corrected by subtracting the ohmic resistance loss (about 9 Ω), the value of which is obtained from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurement (Supplementary Fig. 32). To evaluate the electrochemically active surface area of the catalysts, the Cu underpotential deposition method67,68,69,70 was applied, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 30 and Supplementary Table 3.

To test the faradaic efficiency, the H2 products were analyzed with an online gas chromatography (GC) setup (Agilent 7890B) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector. Argon (≥99.999%) was used as the carrier gas. The Faradaic efficiency (FE) was calculated by comparing the measured amount of H2 generated by cathodal electrolysis with the calculated amount of H2 (assuming an FE of 100%), and the equation is given by:

where the moles of H2 is measured by GC (the calibration is needed in advance through injecting high-purity H2 to GC, and the H2 volume is linearly dependent on GC peak area), Q is obtained from the electrochemical measurements.

Material characterization

The microstructures and morphologies based on MoS2 were characterized by optical microscopy, SEM (FEI 4200), and Raman spectroscopy (Renishaw inVia). Raman spectroscopy was performed with a 514.5 nm laser (with spot size about 1 μm in diameter) at room temperature. The micro-electrochemical measurements were performed using two source meters (Keithley 2400 and 2450). STEM measurements were performed at the SuperSTEM Laboratory, Daresbury, UK, on a Nion UltraSTEM100 aberration-corrected dedicated STEM. The Nion UltraSTEM has a cold field emission gun with a native energy spread of 0.35 eV and was operated at 60 kV acceleration voltage. The beam was set up to a convergence semiangle of 30 mrad with an estimated beam current of ~100 pA. Under these operating conditions, the estimated probe size is ~1.1 Å, providing the perfect tool for atom-by-atom chemical analysis. HAADF imaging was employed to produce atomically resolved images whose intensity is approximately proportional to the square of the average atomic number Z of the material under investigation. This chemically sensitive “Z-contrast” mode is ideally suited to directly identify the nature of individual atoms. All the HAADF images presented here were filtered for visual clarity using a wiener filter with coefficient sigma ranging from 2–5 and 50 iterations in MEM (Maximum Entropy Methods) with fourth order Gaussian filter, as implemented in the STEM-CELL software71,72. Geometrical Phase Analysis (GPA) was carried out using a cosine mask of suitable size and 1 binning base. HRTEM and low-resolution annular dark field (ADF)-STEM images were obtained on a FEI Tecnai F20 field emission gun microscope with a 0.19 nm point-to-point resolution at 200 kV, equipped with an embedded Quantum Gatan Image Filter for EELS analyses. Some STEM characterizations were carried out on a JEOL ARM-200F (S)TEM equipped with CEOS CESCOR aberration corrector, operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. The convergence semiangle and acquisition semiangle were 28–33 and 68–280 mrad for the ADF imaging. The dwell time per pixel was set to 12–20.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yu, Q. et al. Control and characterization of individual grains and grain boundaries in graphene grown by chemical vapour deposition. Nat. Mater. 10, 443 (2011).

Najmaei, S. et al. Vapour phase growth and grain boundary structure of molybdenum disulphide atomic layers. Nat. Mater. 12, 754–759 (2013).

van der Zande, A. M. et al. Grains and grain boundaries in highly crystalline monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Mater. 12, 554–561 (2013).

Chang, S.-Y. & Chang, T.-K. Grain size effect on nanomechanical properties and deformation behavior of copper under nanoindentation test. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 033507 (2007).

Son, D.-Y. et al. Self-formed grain boundary healing layer for highly efficient CH3 NH3 PbI3 perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 1, 16081 (2016).

Li, C. et al. Grain-boundary-enhanced carrier collection in CdTe solar cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 156103 (2014).

Bowman, W. J., Zhu, J., Sharma, R. & Crozier, P. A. Electrical conductivity and grain boundary composition of Gd-doped and Gd/Pr co-doped ceria. Solid State Ion. 272, 9–17 (2015).

Guo, C. F., Sun, T., Liu, Q., Suo, Z. & Ren, Z. Highly stretchable and transparent nanomesh electrodes made by grain boundary lithography. Nat. Commun. 5, 3121 (2014).

Sangwan, V. K. et al. Gate-tunable memristive phenomena mediated by grain boundaries in single-layer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 403 (2015).

Feng, X., Jiang, K., Fan, S. & Kanan, M. W. Grain-boundary-dependent CO2 electroreduction activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4606–4609 (2015).

Li, G. et al. All the catalytic active sites of MoS2 for hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16632–16638 (2016).

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Voiry, D., Yang, J. & Chhowalla, M. Recent strategies for improving the catalytic activity of 2D TMD nanosheets toward the hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 28, 6197–6206 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Self-optimizing, highly surface-active layered metal dichalcogenide catalysts for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Energy 2, 17127 (2017).

Li, H. et al. Activating and optimizing MoS2 basal planes for hydrogen evolution through the formation of strained sulphur vacancies. Nat. Mater. 15, 48–53 (2016).

Kibsgaard, J., Chen, Z., Reinecke, B. N. & Jaramillo, T. F. Engineering the surface structure of MoS2 to preferentially expose active edge sites for electrocatalysis. Nat. Mater. 11, 963 (2012).

Ji, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, Z. Chemical vapour deposition of group-VIB metal dichalcogenide monolayers: engineered substrates from amorphous to single crystalline. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2587–2602 (2015).

Jaramillo, T. F. et al. Identification of active edge sites for electrochemical H2 evolution from MoS2 nanocatalysts. Science 317, 100–102 (2007).

Xie, J. et al. Defect-rich MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets with additional active edge sites for enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 25, 5807–5813 (2013).

Dai, X. et al. Co-doped MoS2 nanosheets with the dominant CoMoS phase coated on carbon as an excellent electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 27242–27253 (2015).

Voiry, D. et al. The role of electronic coupling between substrate and 2D MoS2 nanosheets in electrocatalytic production of hydrogen. Nat. Mater. 15, 1003–1009 (2016).

Ye, G. et al. Defects engineered monolayer MoS2 for improved hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Lett. 16, 1097–1103 (2016).

Ouyang, Y. et al. Activating inert basal planes of MoS2 for hydrogen evolution reaction through the formation of different intrinsic defects. Chem. Mater. 28, 4390–4396 (2016).

Li, S. et al. Vapour–liquid–solid growth of monolayer MoS2 nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 17, 535–542 (2018).

Zhou, J. et al. A library of atomically thin metal chalcogenides. Nature 556, 355–359 (2018).

Gong, Y. et al. Synthesis of millimeter-scale transition metal dichalcogenides single crystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 2009–2015 (2016).

He, Y. et al. Layer engineering of 2D semiconductor junctions. Adv. Mater. 28, 5126–5132 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Chemical vapor deposition growth of crystalline monolayer MoSe2. ACS Nano 8, 5125–5131 (2014).

Gao, Y. et al. Ultrafast growth of high-quality monolayer WSe2 on Au. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700990 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Halide-assisted atmospheric pressure growth of large WSe2 and WS2 monolayer crystals. Appl. Mater. Today 1, 60–66 (2015).

Dathbun, A. et al. Large-area CVD-grown sub-2 V ReS2 transistors and logic gates. Nano Lett. 17, 2999–3005 (2017).

Zhou, J. et al. Large-area and high-quality 2D transition metal telluride. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603471 (2017).

Naylor, C. H. et al. Monolayer single-crystal 1T’-MoTe2 grown by chemical vapor deposition exhibits weak antilocalization effect. Nano Lett. 16, 4297–4304 (2016).

Cui, F. et al. Epitaxial growth of large-area and highly crystalline anisotropic ReSe2 atomic layer. Nano Res. 10, 2732–2742 (2017).

Gao, Y. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform monolayer WS2 on reusable Au foils. Nat. Commun. 6, 8569 (2015).

Empante, T. A. et al. Chemical vapor deposition growth of few-layer MoTe2 in the 2H, 1T’, and 1T phases: tunable properties of MoTe2 films. ACS Nano 11, 900–905 (2017).

Feng, Q. et al. Growth of large-area 2D MoS2(1-x)Se2x semiconductor alloys. Adv. Mater. 26, 2648–2653 (2014).

Wu, S. et al. Vapor–solid growth of high optical quality MoS2 monolayers with near-unity valley polarization. ACS Nano 7, 2768–2772 (2013).

Huang, J.-H. et al. Large-area 2D layered MoTe2 by physical vapor deposition and solid-phase crystallization in a tellurium-free atmosphere. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1700157 (2017).

Kang, K. et al. High-mobility three-atom-thick semiconducting films with wafer-scale homogeneity. Nature 520, 656 (2015).

Kang, K. et al. Layer-by-layer assembly of two-dimensional materials into wafer-scale heterostructures. Nature 550, 229 (2017).

Lee, S.-H., Kwak, E.-H. & Jeong, G.-H. Dewetting behavior of electron-beam-deposited Au thin films on various substrates: graphenes, quartz, and SiO2 wafers. Appl. Phys. A 118, 389–396 (2015).

Seguini, G. et al. Solid-state dewetting of ultra-thin Au films on SiO2 and HfO2. Nanotechnology 25, 495603 (2014).

Li, H. et al. From bulk to monolayer MoS2: evolution of Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 1385–1390 (2012).

Huang, P. Y. et al. Grains and grain boundaries in single-layer graphene atomic patchwork quilts. Nature 469, 389 (2011).

Shi, J., Ji, Q., Liu, Z. & Zhang, Y. Recent advances in controlling syntheses and energy related applications of MX2 and MX2/graphene heterostructures. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1600459 (2016).

Shi, Y., Li, H. & Li, L.-J. Recent advances in controlled synthesis of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides via vapour deposition techniques. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2744–2756 (2015).

Ruffino, F. & Grimaldi, M. G. Controlled dewetting as fabrication and patterning strategy for metal nanostructures. Phys. Status Solidi A 212, 1662–1684 (2015).

Choi, H.-J. Vapor–Liquid–Solid Growth of Semiconductor Nanowires (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Lauritsen, J. V. et al. Size-dependent structure of MoS2 nanocrystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 53–58 (2007).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Trends in the exchange current for hydrogen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, J23–J26 (2005).

Zhou, W. et al. Intrinsic structural defects in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 13, 2615–2622 (2013).

Hansen, L. P. et al. Atomic-scale edge structures on industrial-style MoS2 nanocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 10153–10156 (2011).

Yu, W. J. et al. Vertically stacked multi-heterostructures of layered materials for logic transistors and complementary inverters. Nat. Mater. 12, 246–252 (2013).

Allain, A., Kang, J., Banerjee, K. & Kis, A. Electrical contacts to two-dimensional semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 14, 1195 (2015).

Kang, J., Liu, W., Sarkar, D., Jena, D. & Banerjee, K. Computational study of metal contacts to monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031005 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Field effect enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction of MoS2 nanosheets. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604464 (2017).

Ding, M. et al. An on-chip electrical transport spectroscopy approach for in situ monitoring electrochemical interfaces. Nat. Commun. 6, 7867 (2015).

He, Y. et al. Self-gating in semiconductor electrocatalysis. Nat. Mater. 18, 1098–1104 (2019).

Voiry, D. et al. Conducting MoS2 nanosheets as catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Lett. 13, 6222–6227 (2013).

Nsimama, P. D., Herz, A., Wang, D. & Schaaf, P. Influence of the substrate on the morphological evolution of gold thin films during solid-state dewetting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 388A, 475–482 (2016).

Borciaa, R., B., I. D. & Bestehorn, M. Static and dynamic contact angles- a phase field modelling. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 166, 127–131 (2009).

Artyukhov, V. I., Hu, Z., Zhang, Z. & Yakobson, B. I. Topochemistry of Bowtie- and star-shaped metal dichalcogenide nanoisland formation. Nano Lett. 16, 3696–3702 (2016).

Steinbach, I. & Pezzolla, F. A generalized field method for multiphase transformations using interface fields. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 134, 385–393 (1999).

Ingo, S. Phase-field models in materials science. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 17, 073001 (2009).

Zheng, Y. et al. High electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity of an anomalous ruthenium catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16174–16181 (2016).

Mahmood, J. et al. An efficient and pH-universal ruthenium-based catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 441 (2017).

Green, C. L. & Kucernak, A. Determination of the platinum and ruthenium surface areas in platinum−ruthenium alloy electrocatalysts by underpotential deposition of copper. I. unsupported catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 1036–1047 (2002).

Colmenares, L., Jusys, Z. & Behm, R. J. Electrochemical surface characterization and O2 reduction kinetics of Se surface-modified Ru nanoparticle-based RuSey/C catalysts. Langmuir 22, 10437–10445 (2006).

Grillo, V. & Rotunno, E. STEM-CELL: A software tool for electron microscopy: Part I—simulations. Ultramicroscopy 125, 97–111 (2013).

Grillo, V. & Rossi, F. STEM-CELL: A software tool for electron microscopy. Part 2 analysis of crystalline materials. Ultramicroscopy 125, 112–129 (2013).

Zhan, Y., Liu, Z., Najmaei, S., Ajayan, P. M. & Lou, J. Large-area vapor-phase growth and characterization of MoS2 atomic layers on a SiO2 substrate. Small 8, 966–971 (2012).

Kong, D. et al. Synthesis of MoS2 and MoSe2 films with vertically aligned layers. Nano Lett. 13, 1341–1347 (2013).

Lin, Y.-C. et al. Direct synthesis of van der Waals solids. ACS Nano 8, 3715–3723 (2014).

Song, J.-G. et al. Layer-controlled, wafer-scale, and conformal synthesis of tungsten disulfide nanosheets using atomic layer deposition. ACS Nano 7, 11333–11340 (2013).

Yim, C. et al. High-performance hybrid electronic devices from layered PtSe2 films grown at low temperature. ACS Nano 10, 9550–9558 (2016).

Liu, K.-K. et al. Growth of large-area and highly crystalline MoS2 thin layers on insulating substrates. Nano Lett. 12, 1538–1544 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Z.L. gratefully acknowledges funding supports from Ministry of Education (MOE) under AcRF Tier 1 (M4011782.070 RG4/17 and M4011993.070 RG7/18), AcRF Tier 2 (2015-T2-2-007, 2016-T2-1-131, 2016-T2-2-153, and 2017-T2-2-136), AcRF Tier 3 (2018-T3-1-002), National Research Foundation – Competitive Research Program (NRF-CRP21-2018-0092), and A*Star QTE programme. P.T., S.M.S., J.R.M., and J.A. acknowledge funding from Generalitat de Catalunya 2017 SGR 327 and 1246 and the Spanish MINECO coordinated projects between IREC and ICN2 VALPEC (ENE2017-85087-C2-C3). ICN2 acknowledges support from the Severo Ochoa Program (MINECO, Grant SEV-2017-0706). IREC and ICN2 are funded by the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya. Part of the present work has been performed in the framework of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Materials Science PhD program. S.M.S. acknowledges funding from ‘Programa Internacional de Becas “la Caixa”-Severo Ochoa’. J.R.M. recognizes also its affiliation to University of Barcelona. Part of the electron microscopy aspects of this work were supported by the EPSRC (UK), as the SuperSTEM Laboratory is the EPSRC National Research Facility for Advanced Electron Microscopy. Q.J.W. acknowledges the supports from MOE, Singapore grant (MOE2016-T2-2-159, MOE2016-T2-1-128, and MOE Tier 1 RG164/15) and National Research Foundation, Competitive Research Program (NRF-CRP18-2017-02) and NSFC (61704082) as well as Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20170851). X.W. and B.K.T. gratefully acknowledge funding support from MOE, Singapore (grant no. MOE2015-T2-2-043). H.Z. acknowledges the supports from MOE under AcRF Tier 2 (MOE2015-T2-2-057; MOE2016-T2-2-103; and MOE2017-T2-1-162), AcRF Tier 1 (2016-T1-002-051; 2017-T1-001-150; and 2017-T1-002-119), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) under its AME IRG (Project No. A1783c0009), and NTU under Start-Up Grant (M4081296.070.500000) in Singapore. The authors would like to acknowledge the Facility for Analysis, Characterization, Testing, and Simulation, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, for their electron microscopy and X-ray facilities. H.Z. also thanks the support from ITC via Hong Kong Branch of National Precious Metals Material Engineering Research Center, and the Start-Up Grant from City University of Hong Kong. Theory and simulations work at Rice university (Z.H., L.W., and B.I.Y.) was supported by the Office of Naval Research grant N00014-18-1-2182.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. and Y.H. conceived and initiated the project. Z.L., Q.W., J.A. and M.W. supervised the project and led the collaboration efforts. Y.H. designed the experiments, grew nanograin film, fabricated the electrochemical devices, and performed micro-electrochemical HER measurement. P.T., C.Z. (Dr. Chao Zhu), S.M.S., J.A., J.M. and Q.M.R. performed the TEM and STEM measurements. Z.Hu did the phase-field simulation of the growth process. Y.H., Q.H. and C.Z. (Mr. Chao Zhu) made the micro-electrochemical measurement setup. L.W. (Luqing Wang) and B.Y. performed the first-principles calculations of the catalytic activity. Q.Z. did the SEM measurement. G.G. and A.T. conducted the cross-sectional TEM measurement. Z. Huang and Q.H. performed gas chromatography measurement. P.G., X.W. (Xuewen Wang), W.F., C.G., X.W. (Xingli Wang), B.A., Y.Z., L.W. (Liang Wang), and B.T. assisted the growth of nanograin film. J.X. and A.Z. did the Raman measurements. Y.H., P.T., Z.Hu, Q.W., H.Z., J.A. and Z.L. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jing Gu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Y., Tang, P., Hu, Z. et al. Engineering grain boundaries at the 2D limit for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat Commun 11, 57 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13631-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13631-2

This article is cited by

-

Giant intrinsic photovoltaic effect in one-dimensional van der Waals grain boundaries

Nature Communications (2024)

-

On-device phase engineering

Nature Materials (2024)

-

The practice of reaction window in an electrocatalytic on-chip microcell

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Vapour-phase deposition of two-dimensional layered chalcogenides

Nature Reviews Materials (2023)

-

Topological defects and their induced metallicity in monolayer semiconducting γ-phase group IV monochalcogenides

Science China Materials (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.