Abstract

Cyanophage S-2L is known to profoundly alter the biophysical properties of its DNA by replacing all adenines (A) with 2-aminoadenines (Z), which still pair with thymines but with a triple hydrogen bond. It was recently demonstrated that a homologue of adenylosuccinate synthetase (PurZ) and a dATP triphosphohydrolase (DatZ) are two important pieces of the metabolism of 2-aminoadenine, participating in the synthesis of ZTGC-DNA. Here, we determine that S-2L PurZ can use either dATP or ATP as a source of energy, thereby also depleting the pool of nucleotides in dATP. Furthermore, we identify a conserved gene (mazZ) located between purZ and datZ genes in S-2L and related phage genomes. We show that it encodes a (d)GTP-specific diphosphohydrolase, thereby providing the substrate of PurZ in the 2-aminoadenine synthesis pathway. High-resolution crystal structures of S-2L PurZ and MazZ with their respective substrates provide a rationale for their specificities. The Z-cluster made of these three genes – datZ, mazZ and purZ – was expressed in E. coli, resulting in a successful incorporation of 2-aminoadenine in the bacterial chromosomal and plasmidic DNA. This work opens the possibility to study synthetic organisms containing ZTGC-DNA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

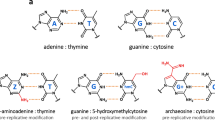

At least since the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), four types of nucleobases — adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) and thymine (T) — are used to encode genetic information in the DNA of all living cells1. This principle can be extended to DNA and RNA viruses (the latter carrying uracil in lieu of thymine), which are important agents of evolution2. However, the genetic material may be subject to nucleobase modifications, for instance to confer an additional, epigenetic information or to provide resistance against restriction-modification systems. Phages T2, T4 and T6 systematically substitute 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC, often glucosylated) for cytosine3,4, protecting the DNA from CRISPR-Cas9 degradation5. Likewise, phage 9g replaces a quarter of its genomic guanine with archaeosine (G+)6, enabling its DNA to resist 71% of cellular restriction enzymes7.

Such alterations are made almost exclusively without changing the Watson–Crick base-pairing scheme. The only known exception to the A:T G:C pairing rule was revealed by the discovery of cyanophage S-2L, from Siphoviridae family8. S-2L abandons the usage of genomic adenine in favour of 2-aminoadenine (2,6-diaminopurine or Z) (Fig. 1a). The resulting ZTGC-DNA has an improved thermal stability9,10 and proves to be almost completely resistant to adenine-targeting restriction enzymes11.

a Chemical structure of Z:T and G:C base pairs constituting S-2L’s ZTGC-DNA. b Genomic map of most important replication genes in all phages with close purZ and datZ homologues, and their phylogeny. The phages can be presently divided into four clades (colours in background to the left) with distinct organization and variants of replication-related genes. The names of these genes, identified by their colours, are shown below. Cyanophage S-2L is, until now, the only representative of its clade. Close scrutiny of the sequence data reveals possible mis-annotation of some viral sequences with bacterial names (“ann.?” note) – their length and content perfectly match other viral sequences.

The key enzyme of Z metabolism was recently identified as PurZ, a homologue of adenylosuccinate synthetases (PurA)12. PurZ of cyanophage S-2L and related vibriophage φVC8 from Podoviridae family create the immediate precursor of 2-aminoadenine deoxyribose monophosphate (dZMP), N6-succino-2-amino-2′-deoxyadenylate monophosphate (dSMP), from standard dGMP and free aspartic acid (Asp) using ATP as the energy donor. The enzymes necessary for the subsequent conversion of dSMP to dZMP and then dZTP have not been found on the phages’ genomes; instead, the non-specific enzymes of V. cholerae complement the pathway of dZTP metabolism of φVC8 in vitro12.

Furthermore, in S-2L a dATP-specific triphosphatase (DatZ) eliminates dATP from the pool of available dNTPs substrates13. This step is essential for conferring an indirect nucleotide specificity to the DNA primase-polymerase (PrimPol) of the cyanophage. Synteny of both purZ and datZ genes in related viruses suggests that dATP depletion is closely tied to dZTP production.

Here, we broaden the substrate spectrum of S-2L’s PurZ and present its structure in a complex with dGMP and dATP as an alternative energy donor. Moreover, along with datZ and purZ we identify a co-conserved gene encoding a MazG-like nucleotide phosphohydrolase (mazZ). We show that MazZ generates (d)GMP from (d)GTP, placing the enzyme directly upstream of PurZ in the 2-aminoadenine synthesis pathway. The crystal structure of MazZ bound to the intermediate product allows to identify crucial catalytic residues, shared with close homologues of the enzyme.

To confirm the necessity and sufficiency of the Z-cluster (datZ, mazZ, purZ) for efficient ZTGC-DNA synthesis in cellulo, we expressed these three genes in Escherichia coli. Although toxic to the bacteria, the system was able to convert a significant amount of DNA’s adenine to 2-aminoadenine both in chromosomal and plasmidic fractions.

Results

Genome of cyanophage S-2L and its relatives: a conserved Z-cluster

Although the genome of phage S-2L was made available in 2004 (GenBank AX955019), homology analysis suggested several sequence errors. We decided to re-sequence it using the next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology with improved quality (GenBank MW334946; Supplementary Fig. 1). The corrected sequence is identical to the previous one with few exceptions. In particular, a mutation in the sequence between datZ and purZ genes prevented the identification of a gene whose product corresponds to a MazG-like phosphohydrolase, named hereafter mazZ. We found no Shine-Dalgarno (SD) motifs upstream the genes, which is consistent with low SD motif conservation in cyanobacteria and their phages14. Interestingly, the S-2L genome can be divided into two parts, where almost all genes follow only one direction of translation; in-between, we identified a marR-type repressor found typically on such junctions15.

We found ten complete phage sequences having both datZ and purZ gene homologues (Fig. 1b), all coming from Spihoviridae or Podoviridae families. We inferred their phylogeny and distributed all phages into four major clusters with similar genome organization; interestingly, among them cyanophage S-2L has a unique replication module. Finally, we observed that the mazZ gene is always co-conserved between datZ and purZ, although in one of two possible variants: MazZ-1 (S-2L-like) and MazZ-2 (φVC8-like). MazZ-1 undergoes frequent N-terminal fusions with other domains, but not in S-2L. In the following, we define the closely co-varying set of genes datZ, mazZ and purZ as the Z-cluster.

S-2L PurZ can function as a dATPase, with no structural selection on 2′-OH

Structural analysis of φVC8 PurZ (PDB ID: 6FM1) suggested no particular selection on the 2′-OH group of bound ATP; thus, we sought to compare the reaction time-course of PurZ with either dATP or ATP as the phosphate donor (Supplementary Fig. 2). Reactions with the purified S-2L protein followed by HPLC show no specificity of the enzyme towards the ribo and deoxy variants (Fig. 2a): it can act as a dATPase, but stays functional after dATP pool depletion by using ATP instead.

a HPLC profiles representing the time-course of the reaction catalyzed by PurZ in presence of dGMP, Asp and dATP/ATP (purple). Pure compounds used as standards are shown below in black. The enzyme generates products corresponding to (d)ADP and dSMP. b Ribbon representation of a PurZ crystallographic protomer, with dGMP and dATP shown in stick (yellow). c Catalytic pocket of PurZ with the 2Fo − Fc electron density contoured around the reactants at 1 σ (black mesh). Crucial residues surrounding the nucleotides are coloured by chain (purple and orange).

We crystallized S-2L PurZ with two of its substrates, dGMP and dATP, and solved its structure at 1.7 Å resolution (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 2b). Both ligands have a binding mode identical to the one of dGMP and ATP described previously in the structure of φVC8 PurZ (PDB ID: 6FM1; Fig. 2c).

PurA enzymes are known to be functional dimers16,17 or even tetramers18. Through crystallographic symmetry, a PurZ dimer can be reconstructed for both S-2L and φVC8 (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Very low B-factors (Supplementary Fig. 3B) suggest an overall high rigidity for the dimer; the only exception is the Y272-L278 loop above the reactants, in contact with the aspartate substrate12. Its crucial tip (T273-T276) is strictly conserved between S-2L and φVC8, both in sequence and structure.

Residues G22, S23, N49, A50, T132, Q190, V241 and the backbone atoms of Y21 form a pocket where the base moiety of dGMP is placed. Y21-S23 are positioned next to the amino group of dGMP in position 2, the hydroxyl group of the conserved S23 being 3.7 Å away from the nitrogen atom. Although this distance is too long for a postulated hydrogen bond12, its polarity may still contribute to the specificity towards guanine; additionally, the partial negative charge of S23’s oxygen is compatible with the close guanidino goup of R280. Residues G130, S131, R146, Y203, C204, T205 and R240 complete the dGMP pocket. In addition, V241 is ideally placed to sterically interfere with the ribose 2′-OH group of ribonucleotides (see below). Notably, R146 from the dimer’s other molecule forms an ion pair with the α-phosphate19.

Like ATP in φVC8 PurZ, the base moiety of dATP is stabilized by stacking interactions with F306 and P336 residues. Oxygen atoms from the side chains of N305, Q308 and the backbone of G335 form hydrogen bonds with adenine’s 6-amino group. Importantly, the amide group of Q308 (N297 in φVC8) would display conflicting polarity with the 2-amino group of bases G and Z. The rest of the ligand interacts with S-2L PurZ almost exclusively through its triphosphate tail with residues S23, G25, G51, H52 and T53; T53 also touches the C3’ atom side. The position inferred for the 2′-OH of ATP would be entirely exposed to the solvent, like in φVC8 PurZ.

Molecular basis for substrate selectivity in PurZ vs PurA

To compare PurZ and PurA, we prepared a structure-informed sequence alignment. Thirty-six residues are strictly conserved between PurZ and PurA, while 24 further residues have only marginal variability (Supplementary Fig. 4). These two sets of residues cluster in the catalytic pocket and the surrounding layer, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5A). Finally, 15 residues are unique to PurZ, but otherwise conserved in PurA. Their placement is intermediate compared to the previous classes, although several such residues (S23, T273 and Q308) interact with the substrates. In PurA, a conserved arginine (R303 in E. coli) balances the partial charge of O2′ of IMP at 2.5-4 Å and interacts with the free aspartate substrate20. The corresponding residues in PurZ extend noticeably further, being 7.9 Å (S-2L R244) and 8.5 Å (φVC8 K267) away from C2′, precluding any possible stabilization of the ribonucleotide. Moreover, in PurZ an insertion (A242-W250 for S-2L) deforms the loop that contains a conserved V241, pulling it slightly closer to the C2′ ribose atom—from 4.3 to 5.3 Å as seen in PurA to 3.7 Å (S-2L) and 3.6 Å (φVC8). Lastly, one of the two deletions specific to PurZ and PurA from Pyrococcus horikoshii12 are compensated by an additional C-terminal helix α11 unique to S-2L (Supplementary Fig. 5B). Using the above alignment, we constructed a phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. 6), which confirms the possible archaeal origin for PurZ.

S-2L MazZ is a (d)GTP-specific NTP-PPase with MazG-HisE fold

Purified MazZ of cyanophage S-2L is capable of removing two terminal phosphates from a nucleoside triphosphate (Fig. 3a). Its preferential substrates, dGTP and GTP, are rapidly dephosphorylated to dGMP and GMP, respectively. In contrast, S-2L MazZ shows no substantial activity with other deoxynucleotides, including dZTP (Supplementary Fig. 7). Interestingly, dGTP-specific MazG enzymes occur in other cyanophages, that are unrelated to S-2L nonetheless21.

a HPLC analysis of S-2L MazZ activity with dGTP and GTP (gold), with nucleotide standards below (black). b A tetramer of MazZ that constitutes the crystallographic asymmetric unit. Each catalytic pocket contains the reactant (lime) and three catalytic ions and results from interactions at the interface of two chains of a tight dimer. c A close-up on the catalytic pocket, in two views. The product of dGTP dephosphorylation (lime) is identified as dGDP in the crystal, next to three catalytic Mn2+ ions (lilac spheres). The determinants of guanine specificity (yellow for N2 and purple for O6, upper panel) and residues coordinating the ions (blue, lower panel) are placed on a single protein chain. The 2Fo−Fc electron density around the ligands is contoured at 1 σ (black mesh); the anomalous signal attesting for the presence of Mn2+ ions is contoured at 3 σ (red mesh).

We obtained crystals of MazZ and solved its structure, bound to the dephosphorylation product of dGTP and catalytic Mn2+ ions, at 1.43 Å resolution (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 3b). Contrary to other members of the all-α NTP-PPase superfamily22, each MazZ protein chain has two additional β-strands at its C-terminus. Together, they form a homotetramer with a typical MazG-HisE fold (Supplementary Fig. 8): to our knowledge, it is the first time that the fold is recognized as identical for all MazG, MazG-like and HisE enzymes, despite the number of determined structures. The whole MazZ tetramer constitutes the asymmetric unit. The only noticeable differences in electron density between superposed chains of the tetramer lie in the solvent-exposed D43-H46 flexible loop and at both N- and C-termini.

The electron density of the dGTP dephosphorylation product revealed the presence of two phosphate groups (Fig. 3c). The dGDP intermediate observed in crystallo is almost completely buried inside the enzyme, except for the solvent-exposed β-phosphate next to which we found three catalytic Mn2+ ions.

From one side, the ligand is held by residues I12, W15, I16, N20, K31, E35, D53, I56, L57 and D60 of one chain. The second chain completes the pocket with residues K76, N80, W85, A92, M93, R94 and H95. The closest residue to guanine’s O6 is N20, through its amide nitrogen at 3.2 Å; the 2-amino group is only 3.0 Å away from the carboxyl group of D60. Altogether, the specificity of MazZ emerges from the cavity volume matching guanine’s shape and its charge compatibility.

We observe no steric hindrance for the possible 2′-OH group. Mutation of the closest I56 could affect the specificity for ribonucleotides; however, it also contacts the base’s 2-amino group and is surrounded by an intricate network of other residues.

The three Mn2+ ions, named A, B and C, are strictly equivalent to the Mg2+ ions found in a related NTP-PPase23. Ion A is coordinated by residues E34, E35 and E38; ion B by E50 and D53; and ion C by E38 and E50. These ions are all coordinated in an octahedral fashion with protein, ligand and water atoms. It is possible that the two-metal-ion mechanism described for NTP-PPases occurs in fact with two consecutive dephosphorylation steps, justifying the presence of the three ions and intermediate dGDP. In addition, residue R83, positioned only 2.8 Å away from the β-phosphate, is probably important for stabilizing the transition state24.

S-2L MazZ as a representative of MazZ-1 subfamily and similarity with MazZ-2

With the exception of E34, all residues of S-2L MazZ coordinating the catalytic ions are strictly conserved across all MazZ-1 homologues (Supplementary Fig. 9). Most of the amino acids participating in nucleotide pocket formation tend to be conserved as well: only the residues I16, N20 and A92 placed around the nucleobase are unique to S-2L. Importantly, residues I56 and D60 are kept by all MazZ-1 homologues, suggesting preserved guanine specificity.

In MazZ-2, four negatively charged residues are also strictly conserved, their position corresponding to E35, E38, E50 and E53 of S-2L MazZ (Supplementary Fig. 10). However, other nucleobase-binding residues differ from MazZ-1 consensus, implying an alternative binding mode of the substrate. Finally, a counterpart of R83 important for the two-metal-ion mechanism is preserved in both variants of MazZ.

Successful conversion of E. coli DNA with S-2L Z-cluster

We now propose a complete 2-aminoadenine metabolic pathway for cyanophage S-2L and related Siphoviridae and Podoviridae phages (Fig. 4a). The post-infection composition of cellular dNTP pool is heavily altered: dATP is eliminated and replaced by dZTP, which is created in turn from dGTP. In the case of cyanophage S-2L, the non-specific Primase-Polymerase (not conserved in other phages possessing the Z-cluster) readily inserts 2-aminoadenine in front of any instructing thymine.

a Native cellular pool of nucleotides is represented in the box to the left; nucleotide pool modified through expression of the viral Z-cluster is shown on the right. Three dots represent unmodified dTTP and dCTP. Structures of S-2L proteins solved in this and previous work13 are shown next to their respective reaction arrows (to scale). Host enzymes (names in grey) finalize the dZTP pathway12. The dotted grey arrow stands for potential use of the standard dNTP pool by PrimPol in the absence of the Z-cluster. b A-to-Z substitution rates in bacterial plasmidic and chromosomal DNA, obtained after complete or partial transplantation of S-2L Z-cluster to E. coli (labels below). Box plot representation highlights data distribution, while black points denote individual expression results (pentaplicates for plasmidic DNA, duplicates for chromosomal DNA). Box whiskers delimit the range of values, box edges mark upper and lower quartiles, vertical lines represent the median, and black crosses—the average. c Accounting for the pre-induction fraction of ATGC-DNA, roughly every fourth plasmidic adenine (green) was changed to 2-aminoadenine (pink) after expressing the Z-cluster.

We put the genes datZ, mazZ and purZ under the control of lac operators on compatible expression plasmids in E. coli and induced the cultures in exponential phase. The whole system proved to be toxic to the cells when expressed (Supplementary Fig. 11). Whether or not it is true for the natural hosts of S-2L and φVC8 is uncertain, but we note that these phages are known to be lytic anyway8,25.

Using mass spectrometry, we were able to quantify the Z content in bacterial DNA (Fig. 4b). In plasmids and the chromosome, cells substituted on average 12.1% and 3.9% of total adenine content with 2-aminoadenine, respectively. In addition, by quantifying the non-modified pre-induction plasmidic fraction, we normalized the plasmidic A-to-Z substitution ratio to 22.7% after expression of the Z-cluster (Fig. 4c). Importantly, incomplete Z-cluster expression yielded lower substitution rates and the effect of datZ and mazZ absence is synergistic. Altogether, it appears that bacterial DNA can be enriched with diaminopurine efficiently with the introduction of the Z-cluster alone.

Discussion

On the day of submitting this paper, we became aware of the work of Zhou et al.26 on the same subject. There, the authors identify three genes conserved in several phages that contain Z in their genome: purZ, also described by one of us and his collaborators12, a gene of dATPase, which is homologous to the datZ gene that we described recently13 and a gene called DUF550, providing the dGMP substrate for the reaction catalysed by PurZ. The latter gene, described in detail for acinetophage SH-Ab 15497, is similar to (but longer than) the mazZ gene that we describe here in phage S-2L, and corresponds to the MazZ-2 variant as shown in Fig. 1b. In SH-Ab 15497 it is apparently both a dATPase and a dGTPase but in S-2L it is only a dGTPase, which underlines some flexibility in the strategy of these phages to incorporate Z instead of A in their genome. Another variation in this strategy comes from the DNA polymerases of ZTGC-DNA phages: all of them but S-2L have a PolA (Pol I) DNA polymerase, that was shown by Pezo et al.27 to have a definite specificity of incorporation of Z vs A in front of T, whereas S-2L has only a PrimPol DNA polymerase, which has no such specificity13.

Pre- and post-replicative modification pathways of genomic thymidine in bacteriophages have already been successfully transplanted to E. coli28 or found to be active in its lysates29. However, these changes involved groups protruding on the outside of the double helix major groove, as in epigenetic modifications. In the case of 2-aminoadenine, the additional amino group on the Watson–Crick edge profoundly modifies the stability of base pairs between the two nucleic acid strands, changing the thermodynamics of the DNA molecule rather than its external accessibility.

The kinetics of creating dZTP from dGTP has to be fine-tuned by the infecting viruses, as dGTP is also a crucial substrate for the synthesis of ZTGC-DNA. We note that in in vitro assays S-2L PurZ is overall less active than the homologous E. coli PurA (Supplementary Fig. 2), which may contribute to this effect.

In addition, we show here that the Klenow fragment of E. coli Pol I, a DNA polymerase participating in plasmid replication30, does not discriminate between A and Z whatsoever (Supplementary Fig. 12). This relaxed specificity holds true for most DNA and RNA polymerases31 and explains the presence of Z in the DNA synthesized entirely by cellular enzymes. Hosts of phages such as S-2L and φVC8 could in principle synthesize ZTGC-DNA during the replicative stage of viral infection. However, aside from the aforementioned Z-cluster toxicity, bacterial replication may be controlled and stopped by the phages.

Lastly, the possible role of methyltransferases in the arms race of phages against bacteria can be briefly discussed: methyltransferases of E. coli were shown to methylate sequences containing 2-aminoadenine in vitro, although they do so with a catalytic efficiency lower by at least an order of magnitude than for regular ATGC-DNA32,33. In addition, phages T3 and T7 lacking the Z-cluster but belonging to the same order as S-2L and φVC8, Caudovirales, seem to undergo marginal in vivo methylation, even in mutants deprived of methylase inhibitors34. Despite the fact that 6-methyl-2-aminoadenine confers endonuclease resistance35, the effect of methylation should be small for the phages of interest or for synthetic cellular ZTGC-DNA.

The toxic effect of 2-aminoadenine in ATGC-DNA organisms such as E. coli probably stems from the complexity of the regulation of DNA transactions: sigma factors are sensitive to A-to-Z substitutions36, while replication origins are known to require AT-rich sequences where melting is facilitated37. Nonetheless, the melting point of a Z:T homopolymer was found to be intermediate between the A:T and G:C ones38. Attuning the cellular machinery for the presence of 2-aminoadenine should thus be in principle achievable, as it is possible for the less complex phages, potentially leading to a pure ZTGC-DNA synthetic organism.

Methods

S-2L genome sequencing, annotation and homology with other bacteriophages

S-2L DNA was isolated from phage lysate of Synechococcus elongatus culture, adapting the techniques commonly used for phage λ DNA. The S-2L genomic library was prepared by successive DNA fragmentation, adaptor ligation, and amplification by GATC Biotech. Libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq. 14,198,980 sequenced reads (2 × 150 bp) were obtained, covering 4,259,694,000 bases. Resulting reads were mapped against the GenBank AX955019.1 S-2L reference sequence using Minimap2 v2.1739. Variant calling was carried out by Freebayes v1.3.240 and later filtered by VCFLIB41. A consensus sequence was generated using VCF Consensus Builder v0.1.042. Annotation of the consensus sequence was carried out by translated BLAST43. Representation of the S-2L genome was made with SnapGene Viewer44. Genomic positions of genes of interest are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Nucleotide and protein sequences of genes purZ, mazZ, datZ, pplA, their synthetic versions and their products are specified in Supplementary Tables 3–5.

Phages related to S-2L through purZ and datZ genes were found by homology searches using NCBI BLAST43, with protein sequences as separate queries. Conserved unknown genes were assessed for possible homology with known proteins using BLAST and HHpred45.

Variants MazZ-1 and MazZ-2 correspond to two sets of MazG-like family proteins whose genes are co-conserved with purZ and datZ. In each set, they have an average 44% (±6) and 43% (±9) protein sequence identity; BLAST does not find any significant hits between the two sets. Distant identity of 31% is observed only for Ochrophage vB_OspB_OH MazZ-2 and the additional N-terminal domain of Salmophage PMBT28 fused to the C-terminal MazZ-1 sequence. Difference between MazZ-1 and MazZ-2 is further highlighted by divergent conservation profiles presented in Supplementary Data.

Protein expression and purification

Synthetic genes for expressed proteins were optimized for E. coli and synthesized using Thermo Fisher’s GeneArt service. Genes were cloned into modified pRSF1-Duet expression vector with a TEV-cleavable N-terminal 14-histidine tag46 using New England Biolabs and Anza (Thermo Fisher Scientific) enzymes. E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL cells (Agilent) were separately transformed with engineered plasmids. Bacteria were cultivated at 37 °C in LB medium with appropriate antibiotic selection (kanamycin and chloramphenicol), and induced at OD = 0.6–1.0 with 0.5 mM IPTG. After incubation overnight at 20 °C, cells were harvested and homogenized in suspension buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 400 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole. After sonication and centrifugation of bacterial debris, corresponding lysate supernatants were supplemented with Benzonase (Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 μl and 1 tablet per 50 ml, respectively. Proteins of interest were isolated by purification of the lysate on Ni-NTA column (suspension buffer as washing buffer, 500 mM imidazole in elution buffer). Histidine tags were removed from the proteins by incubation with His-tagged TEV enzyme overnight. After removing TEV on Ni-NTA column, proteins were further purified on Superdex 200 10/300 column with 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300 mM NaCl. All purification columns were from Life Sciences. Protein purity was assessed on an SDS gel (BioRad). The enzymes were concentrated to 10–19.5 mg ml−1 with Amicon Ultra 10k and 30k MWCO centrifugal filters (Merck), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored directly at −80 °C, with no glycerol added.

Nucleotide HPLC analysis

Thirty micromolar (1.25 mg ml-1) of S-2L PurZ or 4.2 µM (0.2 mg ml−1) of E. coli PurA was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h (if not stated otherwise) with 2 mM of respective nucleotides and 10 mM of aspartate, in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 5 mM MgSO4. For S-2L MazZ, 10 µM of the enzyme was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min with 100 µM of respective nucleotides, in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 and 5 mM MgCl2. Reaction products were separated from the protein using 10,000 MWCO Vivaspin-500 centrifugal concentrators and stored at −20 °C. Products and standards were assayed separately, using around 40 nmol of each for anion-exchange HPLC on DNA-PAC100 (4 × 50 mm) column (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After equilibration with 150 μl of a suspension buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.5% acetonitrile), nucleotides were injected on the column and eluted with 3 min of isocratic flow of the suspension buffer followed by a linear gradient of 0–200 mM NH4Cl over 12 min (1 ml min−1). Eluted nucleotides were detected by absorbance at 260 nm, measured in arbitrary units [mAu]. High-purity nucleotides and chemicals were bought from Sigma-Aldrich, and HPLC-quality acetonitrile was from Serva.

Crystallography and structural analysis

All crystallization conditions were screened using the sitting drop technique on an automated crystallography platform47 and were reproduced manually using the hanging drop method with ratios of protein to well solution ranging from 1:2 to 2:1. PurZ was screened at 19 mg ml−1 with a molar excess of 1.2 of dGMP at 4 °C. Capped thick rods grew over several days in 15% v/v Tacsimate and 2% w/v PEG 3350 buffered with 100 mM HEPES pH 7, and did not appear in the absence of dGMP. MazZ was screened at 14.7 mg ml−1 with a molar excess of 1.2 of dGTP at 18 °C. Big bundles of thin needles grew over a week in 200 mM Li2SO4 and 1.26 M (NH4)2SO4 buffered with 100 mM Tris pH 8.5. PurZ crystals were soaked for 15 min in a solution containing 30% glycerol, 50% dATP solution (100 mM) and 20% crystallization buffer; MazZ crystals were soaked for several seconds with 30% glycerol and 70% crystallization buffer, with added 30 mM MnCl2. All crystals were then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Crystallographic data were collected in a nitrogen gas stream (~100 K) at the Soleil synchrotron in France (beamlines PX1 and PX2), processed by XDS48 with the XDSME49 pipeline and refined in Phenix50. Nucleotide constraints for structure refinement were obtained using Grade Web Server51. The structure of S-2L PurZ was solved by molecular replacement with φVC8 PurZ model (PDB ID: 6FM1). The structure of MazZ was solved using anomalous signal from bound Mn2+ ions that guided automatic model building in Phenix AutoSol, with final manual reconstruction steps using Coot52. PurZ quaternary structure analysis was performed using PISA53 and suggested the presence of a stable dimer.

The presence of two phosphate groups in dGTP dephosphorylation product bound to MazZ was confirmed by a careful analysis of electron density and B-factors, eliminating the possibility of a flexible γ-phosphate. Electron density corresponding to ions A, B and dGDP was also observed in a structure from a crystal not soaked in MnCl2. HPLC analysis of dGTP substrate in solution excluded dGDP contamination.

Transplantation of the Z-cluster into E. coli and 2-aminoadenine detection

Gene datZ was cloned onto plasmid pET100/D-TOPO providing ampicillin resistance. Genes purZ and mazZ were cloned into modified pRSF1-Duet providing kanamycin resistance, in slots 1 (his-tagged) and 2, respectively, each with a ribosome-binding site upstream. Constructs with partial Z-cluster did not include mazZ in pRSF1-Duet slot 2 (datZ/purZ or purZ alone) and further had datZ replaced by mazZ on pET100/D-TOPO (mazZ/purZ). One or both plasmids were used to transform E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL cells.

Bacteria were cultivated at 37 °C in LB medium with appropriate antibiotic selection and induced with 1 mM IPTG at OD = 0.60 (±0.03), or with 84 μM IPTG at varying OD for toxicity tests. After 2 h of further incubation, plasmids were isolated with NucleoSpin Plasmid QuickPure kit (Macherey-Nagel) and suspended in water. When not induced, natural leaking of the promotors resulted in 0.01% of Z content, which was not lethal to the cells. In addition, we observed that the expression of DatZ lowers the overall plasmidic DNA yield, that can be partially compensated when both MazZ and PurZ are expressed as well; this is in line with the proposed 2-aminoadenine metabolism pathway.

Chromosomal and plasmidic DNA was digested to nucleosides with Nucleoside Digestion Mix (NEB) and separated on Amicon Ultra-0.5 mL 10 K centrifugal filters. Nucleosides were analyzed by LCMS, with standard nucleoside controls (Sigma-Aldrich) or dZ (Biosynth Carbosynth). dZ was found to elute at the same position as dG, but with strikingly different MS/MS profiles.

The A-to-Z substitution rate was taken as a ratio of dZ content to dZ+dA. For plasmids, this number was further normalized to the post-induction fraction by calculating the ratio between the pre-induction and final plasmidic DNA yield.

Structure and sequence alignments, phylogeny

Structures homologous to PurZ available in PDB were identified using Dali server54. The sequences were aligned in PROMALS3D55 using structural data supplemented by full protein sequences. Graphical multialignments were prepared with ESPript 356. PurZ/DatZ multialignment was made by aligning concatenated PurZ and DatZ sequences in the default MUSCLE algorithm in MEGA X software57. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were prepared with MEGA X with default parameters, with 100 bootstrap replications. Protein structures were analyzed with Chimera58 or Pymol59. Distances in PurA molecules were measured using PDB IDs 1P9B, 5I34, 5K7X (Arg-O2’ of IMP) and 1P9B, 2DGN, 2GCQ, 4M9D, 5I34, 5K7X (Val-C2’); for φVC8 PurZ measurements, PDB ID 6FKO was used.

DNA polymerase assay

Fluorescence-based polymerase activity test was executed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7 and 5 mM MgCl2, with 3 μM of dT24 overhang DNA template, 1 μM of FAM 5′-labelled DNA primer and various concentrations of either dATP or dZTP. The Klenow polymerase was added to final concentration of 5 U in 50 μl. The assay was conducted at 37 °C for 5 min. Before adding the protein, DNA was hybridized by heating up to 95 °C and gradually cooling to reaction temperature. Reactions were terminated by adding two volumes of a buffer containing 10 mM EDTA, 98% formamide, 0.1% xylene cyanol and 0.1% bromophenol blue, and stored at 4 °C. Products were preheated at 95 °C for 10 min, before being separated with polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by FAM fluorescence on Typhoon FLA 9000 imager. All oligonucleotides were from Eurogentec, chemicals from Sigma-Aldrich, Klenow polymerase from Takara Bio, dATP from Fermentas (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and dZTP from TriLink BioTechnologies. Oligonucleotide sequences are specified in Supplementary Table 6.

Statistics and reproducibility

All non-crystallographic experiments were done in triplicates (n = 3) unless stated otherwise. For X-ray crystallography, several consistent datasets were collected from multiple crystals; the best-resolution datasets were chosen for the final refinements.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The NGS sequence of cyanophage S-2L is deposited in the GenBank database, under the accession code MW334946. The crystallographic data for cyanophage S-2L proteins PurZ and MazZ bound to their respective ligands are deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession codes 7ODX [https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb7ODX/pdb] and 7ODY [https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb7ODY/pdb]. Other data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Koonin, E. V. Comparative genomics, minimal gene-sets and the last universal common ancestor. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1, 127–136 (2003).

Forterre, P. The origin of viruses and their possible roles in major evolutionary transitions. Virus Res. 117, 5–16 (2006).

Wyatt, G. R. & Cohen, S. S. The bases of the nucleic acids of some bacterial and animal viruses: the occurrence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Biochem. J. 55, 774–782 (1953).

Lehman, I. R. & Pratt, E. A. On the structure of the glucosylated hydroxymethylcytosine nucleotides of coliphages T2, T4, and T6. J. Biol. Chem. 235, 3254–3259 (1960).

Bryson, A. L. et al. Covalent modification of bacteriophage T4 DNA inhibits CRISPR-Cas9. mBio 6 (2015).

Thiaville, J. J. et al. Novel genomic island modifies DNA with 7-deazaguanine derivatives. PNAS 113, E1452–E1459 (2016).

Tsai, R., Corrêa, I. R., Xu, M. Y. & Xu, S. Restriction and modification of deoxyarchaeosine (dG +)-containing phage 9 g DNA. Sci. Rep. 7, 8348 (2017).

Kirnos, M. D., Khudyakov, I. Y., Alexandrushkina, N. I. & Vanyushin, B. F. 2-Aminoadenine is an adenine substituting for a base in S-2L cyanophage DNA. Nature 270, 369 (1977).

Khudyakov, I. Y., Kirnos, M. D., Alexandrushkina, N. I. & Vanyushin, B. F. Cyanophage S-2L contains DNA with 2,6-diaminopurine substituted for adenine. Virology 88, 8–18 (1978).

Cristofalo, M. et al. Nanomechanics of diaminopurine-substituted DNA. Biophys. J. 116, 760–771 (2019).

Szekeres, M. & Matveyev, A. V. Cleavage and sequence recognition of 2,6-diaminopurine-containing DNA by site-specific endonucleases. FEBS Lett. 222, 89–94 (1987).

Sleiman, D. et al. A third purine biosynthetic pathway encoded by aminoadenine-based viral DNA genomes. Science 372, 516–520 (2021).

Czernecki, D. et al. How cyanophage S-2L rejects adenine and incorporates 2-aminoadenine to saturate hydrogen bonding in its DNA. Nat. Commun. 12, 2420 (2021).

Wei, Y. & Xia, X. Unique Shine–Dalgarno sequences in cyanobacteria and chloroplasts reveal evolutionary differences in their translation initiation. Genome Biol. Evol. 11, 3194–3206 (2019).

Perera, I. C. & Grove, A. Molecular mechanisms of ligand-mediated attenuation of DNA binding by MarR family transcriptional regulators. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 243–254 (2010).

Wang, W., Gorrell, A., Honzatko, R. B. & Fromm, H. J. A study of Escherichia coli adenylosuccinate synthetase association states and the interface residues of the homodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7078–7084 (1997).

Jayalakshmi, R., Sumathy, K. & Balaram, H. Purification and characterization of recombinant Plasmodium falciparum adenylosuccinate synthetase expressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 25, 65–72 (2002).

Mehrotra, S. & Balaram, H. Kinetic characterization of adenylosuccinate synthetase from the thermophilic archaea Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Biochemistry 46, 12821–12832 (2007).

Poland, B. W. et al. Crystal structure of adenylosuccinate synthetase from Escherichia coli. Evidence for convergent evolution of GTP-binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 25334–25342 (1993).

Wang, W., Poland, B. W., Honzatko, R. B. & Fromm, H. J. Identification of arginine residues in the putative L-aspartate binding site of Escherichia coli adenylosuccinate synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13160–13163 (1995).

Rihtman, B. et al. Cyanophage MazG is a pyrophosphohydrolase but unable to hydrolyse magic spot nucleotides. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 11, 448–455 (2019).

Moroz, O. V. et al. Dimeric dUTPases, HisE, and MazG belong to a new superfamily of all-α NTP pyrophosphohydrolases with potential “house-cleaning” functions. J. Mol. Biol. 347, 243–255 (2005).

Moroz, O. V. et al. The crystal structure of a complex of Campylobacter jejuni dUTPase with substrate analogue sheds light on the mechanism and suggests the “basic module” for dimeric d(C/U)TPases. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 1583–1597 (2004).

Kim, E. E. & Wyckoff, H. W. Reaction mechanism of alkaline phosphatase based on crystal structures: two-metal ion catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 218, 449–464 (1991).

Solís-Sánchez, A. et al. Genetic characterization of ØVC8 lytic phage for Vibrio cholerae O1. Virol. J. 13, 47 (2016).

Zhou, Y. et al. A widespread pathway for substitution of adenine by diaminopurine in phage genomes. Science 372, 512–516 (2021).

Pezo, V. et al. Noncanonical DNA polymerization by aminoadenine-based siphoviruses. Science 372, 520–524 (2021).

Mehta, A. P. et al. Replacement of thymidine by a modified base in the Escherichia coli genome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 7272–7275 (2016).

Lee, Y.-J. et al. Identification and biosynthesis of thymidine hypermodifications in the genomic DNA of widespread bacterial viruses. PNAS 115, E3116–E3125 (2018).

Camps, M. & Loeb, L. A. When Pol I goes into high gear: processive DNA synthesis by Pol I in the cell. Cell Cycle 3, 114–116 (2004).

Bailly, C. & Waring, M. J. The use of diaminopurine to investigate structural properties of nucleic acids and molecular recognition between ligands and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 4309–4314 (1998).

Marzabal, S. et al. Dam methylase from Escherichia coli: kinetic studies using modified DNA oligomers: hemimethylated substrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 3648–3655 (1995).

Brennan, C. A., Cleve, M. D. V. & Gumport, R. I. The effects of base analogue substitutions on the methylation by the EcoRI modification methylase of octadeoxyribonucleotides containing modified EcoRI recognition sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 7279–7286 (1986).

Krüger, D. H. et al. DNA methylation of bacterial viruses T3 and T7 by different DNA methylases in Escherichia coli K12 cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 150, 323–330 (1985).

Brennan, C. A., Van Cleve, M. D. & Gumport, R. I. The effects of base analogue substitutions on the cleavage by the EcoRI restriction endonuclease of octadeoxyribonucleotides containing modified EcoRI recognition sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 7270–7278 (1986).

Feklistov, A. & Darst, S. A. Structural basis for promoter −10 element recognition by the bacterial RNA polymerase σ subunit. Cell 147, 1257–1269 (2011).

Rajewska, M., Wegrzyn, K. & Konieczny, I. AT-rich region and repeated sequences – the essential elements of replication origins of bacterial replicons. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 408–434 (2012).

Sági, J., Szakonyi, E., Vorlíčková, M. & Kypr, J. Unusual contribution of 2-aminoadenine to the thermostability of DNA. J. Biomol Struct. Dyn. 13, 1035–1041 (1996).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Garrison, E. & Marth, G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1207.3907 (2012).

Garrison, E., Kronenberg, Z. N., Dawson, E. T., Pedersen, B. S. & Prins, P. Vcflib and tools for processing the VCF variant call format. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.21.445151 (2021).

Kruczkiewicz, P. VCF Consensus Builder (Python Package Index repository, 2019).

Wheeler, D. L. et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 28–33 (2003).

SnapGene software(Insightful Science; available at snapgene.com, 2021).

Zimmermann, L. et al. A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new hhpred server at its core. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2237–2243 (2018).

Sauguet, L., Raia, P., Henneke, G. & Delarue, M. Shared active site architecture between archaeal PolD and multi-subunit RNA polymerases revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nat. Commun. 7, 12227 (2016).

Weber, P. et al. High-throughput crystallization pipeline at the crystallography core facility of the Institut Pasteur. Molecules 24, 4451 (2019).

Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Cryst. D. 66, 125–132 (2010).

Legrand, P. XDS Made Easier(GitHub repository, 2017).

Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Cryst. D. 75, 861–877 (2019).

Bricogne, G. et al. BUSTER version 1.2.13. Global Phasing Ltd (2017).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. D. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007).

Holm, L. Benchmarking fold detection by DaliLite v.5. Bioinformatics. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz536. (2019).

Pei, J., Kim, B.-H. & Grishin, N. V. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2295–2300 (2008).

Robert, X. & Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 (2014).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Computat Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8 Schrödinger, LLC (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Crystallogenesis and Crystallography Platform (PF6) of Institut Pasteur for help in crystallization and preliminary crystallographic data collection. We thank Marcel Hollenstein and his group for the use of their HPLC system. We also thank staff from PROXIMA−1 and PROXIMA-2 beamlines for help in data collection and SOLEIL (Saint-Aubin, France) and for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities. We thank Pierre Legrand for discussions regarding the structural aspect of this work, as well as Laurent Debarbieux and his group for discussions regarding phages. We also thank Stéphane Decorps-Declere from the Hub de Bioinformatique et Biostatistique (C3BI, Institut Pasteur) for help with the S-2L genome mapping and its deposition. The authors acknowledge a DIM1Health 2019 grant from the Région Ile de France to the project EpiK (coordinated by P.B. Arimondo) for the LCMS equipment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D. directed the study. D.C. and M.D. designed the study. D.C., F.B. and P.-A.K. performed experiments. D.C., F.B., P.-A.K. and M.D. analyzed the data. D.C. and M.D. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The work on the possibility to use this triad of genes to put the 2-aminoadenine base in the genome of a bacterium is the subject of a U.S. provisional patent application No. 63/172.070 filed on April 07, 2021 entitled “2-AMINOADENINE MODIFIED NUCLEIC ACIDS, CELLS COMPRISING THEM, AND METHODS OF PRODUCING THEM” by D.C., P.-A.K and M.D. F.B. declares no competing interest.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Mariusz Jaskolski and Shuang-yong Xu for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Czernecki, D., Bonhomme, F., Kaminski, PA. et al. Characterization of a triad of genes in cyanophage S-2L sufficient to replace adenine by 2-aminoadenine in bacterial DNA. Nat Commun 12, 4710 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25064-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25064-x

This article is cited by

-

The NMR structure of the Ea22 lysogenic developmental protein from lambda bacteriophage

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Alternative Z-genome biosynthesis pathway shows evolutionary progression from Archaea to phage

Nature Microbiology (2023)

-

Mechanisms supporting aminoadenine-based viral DNA genomes

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.