Abstract

We present a scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and ab-initio study of the anisotropic superconductivity of 2H-NbSe2 in the charge-density-wave (CDW) phase. Differential-conductance spectra show a clear double-peak structure, which is well reproduced by density functional theory simulations enabling full k- and real-space resolution of the superconducting gap. The hollow-centered (HC) and chalcogen-centered (CC) CDW patterns observed in the experiment are mapped onto separate van der Waals layers with different electronic properties. We identify the CC layer as the high-gap region responsible for the main STM peak. Remarkably, this region belongs to the same Fermi surface sheet that is broken by the CDW gap opening. Simulations reveal a highly anisotropic distribution of the superconducting gap within single Fermi sheets, setting aside the proposed scenario of a two-gap superconductivity. Our results point to a spatially localized competition between superconductivity and CDW involving the HC regions of the crystal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Collective phenomena such as superconductivity and charge- or spin-density modulations have been found to co-exist in many materials, the interplay among these correlations being discussed in terms of their competition or mutual enhancement1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The layered transition-metal dichalcogenide 2H-NbSe2 is a prominent example undergoing a transition into a charge-ordered phase at T ≤33 K, and into the superconducting phase at Tc ≤ 7.2 K. Both orderings are driven by electron-phonon coupling23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 with a strong momentum dependence14,17,20,32. The superconducting gap turns out to have an anisotropic distribution over the Fermi surface (FS), whereby NbSe2 has been interpreted either as a multigap or a highly anisotropic superconductor32,33,34,35,36.

A clear understanding of the structure of the superconducting gap is indeed presently missing, and is one of the key unsolved questions about NbSe2. Knowing whether superconducting anisotropy favors the stability of the superconducting state (like, e.g., in MgB2) is interesting on itself. More importantly, accessing the momentum-dependent structure of the superconducting gap in the CDW phase would allow one to unveil the link between superconducting condensation and CDW ordering in this material, resolving the long-standing debate on their competition.

In this paper, we present clear evidence of anisotropic superconductivity in NbSe2 by measuring the tunneling density of states (DOS) with unprecedented resolution combined with state-of-the-art first-principles simulations of the superconducting state based on density functional theory for superconductors (SCDFT). We emphasize that, unlike conventional approaches to superconductivity37,38,39, SCDFT does not rely on any empirical parameter, which allows us to elucidate the strength and distribution of the superconducting gap.

Results

STM spectroscopy

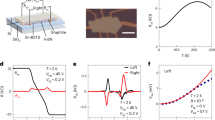

An atomically resolved constant-current STM image is shown in Fig. 1a. Besides the atomic corrugation of the terminating Se layer, the image reveals the modulation of the local DOS imposed by the CDW. As the CDW is incommensurate with the atomic lattice, (periodicity \(\vert{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}_{\tiny{{{{\mbox{CDW}}}}}}\vert\lesssim 2\pi /\left(3a\right)\), where a is the in-plane lattice constant), different local patterns appear across the surface. The area in the orange rectangle shows a triangular pattern as a result of the maximum of the CDW being centered on a hollow site (hollow-centered, HC pattern). This continuously transforms into the chalcogen-centered (CC) pattern highlighted in the blue rectangle. Differential-conductance (dI/dV) spectra in different regions of the CDW are shown in Fig. 1b (for more spectra, see Supplementary Notes 4–6). All spectra exhibit a fully gapped region flanked by a broad peak distribution in the range 2.1 mV < Δ/e < 3.1 mV, with peculiar intensity variations, which can only be resolved by employing a superconducting tip.

a Constant-current image of a clean NbSe2 surface (recorded with a Nb tip at a set point of 10 mV, 100 pA; the scale bar is 2 nm) to illustrate the smooth evolution of the CDW with respect to the atomic lattice. The frames highlight regions where the CDW maxima fall on a hollow site (orange) or on a Se atom (blue). b Differential-conductance dI/dV spectra taken at the positions indicated by stars in (a), recorded in constant-height mode (feedback was opened at the position of the blue spectrum for both traces with a set point of 5 mV, 250 pA and a modulation of 15 μVrms).

Simulations - structural and normal-state properties

The CDW instability is captured by density functional theory (DFT) calculations in the undistorted cell (Ω1), where it manifests itself in imaginary phonon frequencies occurring over a broad range of momenta centered at qCDW40. As discussed in23,28,29, the CDW can not be viewed as a purely electronic Peierls’ instability driven by FS nesting, but is instead a structural phase transition assisted by the enhancement of the electron-phonon coupling (EPC) at the characteristic wave vector. Additionally, the CDW transition temperature can be accurately reproduced in DFT calculations by including anharmonic effects in the lattice dynamics41. In this paper we carry out a DFT study of the superconducting state in the CDW phase, providing a first-principles interpretation of the STM data.

We approximated the incommensurate CDW vector by \({{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}_{\tiny{{{{\mbox{CDW}}}}}}=\left(1/3,0,0\right)2\pi /a\), performing simulations within a superstructure unit cell (Ω3×3) 3 × 3 × 1 times Ω1. The CDW reconstruction was obtained by relaxing the lattice along the phonon instabilities until all the modes were stable in a 2 × 2 × 4 q-grid of the Ω3×3 cell.

We found that the CDW formation induces small-amplitude atomic displacements reducing the minimum Nb–Se distance by ~1.0%. Remarkably, the dynamically stable reconstruction that we predict has a unit cell with two crystallographically inequivalent NbSe2 layers, L1 and L2. These are shown in Fig. 2c,d and correspond, respectively, to the HC and CC patterns observed in experiment. We note that the obtained structures closely resemble those suggested in refs. 17,18,42. The calculated CDW stabilization energy is of 3.7 meV per formula unit.

a Unfolded band structure and (b) electronic DOS of the CDW (green) and undistorted phase (black). CDW reconstruction of layers (c) L2, chalcogen-centered pattern, and (d) L1, hollow-centered pattern, in the Ω3×3 unit cell (blue frame). The modulation of the atomic positions is highlighted by using a 2.53 Å cutoff for the plotted Nb–Se bond-sticks.

The CDW distortion is expected to induce relatively small changes of the electronic structure. Figure 2a,b compares the computed band structure and electronic DOS in the presence of the CDW and in the undistorted system. The two DOSs differ mainly by a broad dip developing in the CDW state slightly above the Fermi level, such that the reduction in the DOS at the Fermi level (NF) induced by the CDW is relatively small (about 10%). Due to the large size of the supercell used in the calculations (54 atoms), the BZ folding makes the band structure in the CDW state hard to interpret. We thus employed a technique of band unfolding43,44 from the supercell BZ to the larger BZ of the Ω1 unit cell. As one can see, the CDW and undistorted bands largely overlap. A closer inspection, however, reveals band gap openings at several points of the BZ path, especially along the MK line, as well as energy shifts at the K point throughout the entire valence-band width.

The CDW effect on the electronic structure can be seen more clearly by considering a horizontal cut through the BZ. Fig. 3a shows the CDW reconstruction of the FS at kz = 0 obtained from the unfolding procedure. The unperturbed FS sheets (blue curves) are included for direct comparison. A double-walled cylindrical sheet of Nb 4d bands and a pocket of Se 4p character are centered at the Γ point. A second pair of Nb 4d-derived FS cylinders is located at the K point. This last double sheet appears to be significantly broader and blurred, indicating a stronger effect of the CDW distortion. Missing segments of the FS crossing the MK line, signal the openings of the CDW gap, which occur in excellent agreement with the ARPES measurements of refs. 32,45.

a kz = 0 cut of the NbSe2 Fermi surface obtained by unfolding the BZ. Color scale indicates the relative spectral weight. Blue curves represent the unperturbed FS sheets. b Electron–phonon coupling and (c) low-temperature superconducting gap computed in the unfolded BZ at random points on constant-kz slices (of \(0.1\frac{\pi }{c}\) width) and within ±0.1 mRy from the Fermi level. d Distribution of gap values computed over the full BZ (green) and the \(| {{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}_{z}| < 0.1\frac{\pi }{c}\) slice (red).

As already mentioned, the complexity of the CDW state is increased by the fact that the two structural layers undergo different reconstructions. To account for this aspect, we considered projections of the FS quasiparticle states onto the layers. Selected cuts of the unfolded projected FS are shown in Fig. 4. Most of the states (displayed in white) are found to span the entire crystal, yet a significant fraction is strongly localized on one layer. L1 states are highlighted in red on the left panel of the figure, while L2 states are shown in blue on the right. We observe significant differences: (i) On the kz = 0 plane, the FS of L2 develops ring structures, unlike L1. (ii) At \({{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}_{z}\simeq \frac{2}{3}\frac{\pi }{c}\) the inner K-centered sheet is mainly composed by L2 states, whereas it has a stronger L1 character on the ΓKM plane. (iii) By projecting the Fermi-pocket resolved DOS onto the layers,

where \({P}_{n{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}^{i}\) is a projection operator with i = L1, L2, and D refers to Γ- or K-centered sheets, we found that, remarkably, \({N}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}^{{{{{{{\rm{L}}}}}}}_{1}{{{{{\boldsymbol{\Gamma }}}}}}}\) and \({N}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}^{{{{{{{\rm{L}}}}}}}_{1}{{{{{\bf{K}}}}}}}\) are equally affected by the CDW (being reduced by 20%), whereas the DOS of L2 stays almost constant. The calculated values of \({N}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}^{iD}\) are listed in Table 1.

The CDW modulation can strongly affect the lattice dynamics and, in turn, influence phonon-driven superconductivity in complex ways. In principle, the CDW can co-exist with and even enhance superconductivity. This latter scenario, in particular, has been put forth by recent experimental findings2,3,4,5,6,7,11,14,15,16,19,21,22,32. As a first step to clarify the CDW effect on the superconducting properties of NbSe2, we simulated the lattice dynamics in the CDW phase. We point out that this is a computationally demanding task because of the large size of the crystallographic unit cell and the accuracy required in simulating the small CDW distortion.

We found that the phonon DOSs in the CDW and undistorted structure have a very similar shape. The unstable phonon mode, appearing with imaginary frequency in the latter, has, in fact, low spectral weight. Nevertheless, the CDW transition significantly alters the EPC: since the EPC strength, \({\left|{g}_{n{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}n^{\prime} {{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}^{\prime} }^{\nu }\right|}^{2}\), is inversely proportional to the phonon frequency37,46,47, a dynamical instability of the lattice shows up in a divergence of the coupling. The calculated α2F(ω) for the dynamically stable 3 × 3 × 1 CDW structure (shown in Supplementary Note 1) gives a total EPC of λ = 1.4, placing NbSe2 in the strong-coupling regime.

To assess the momentum anisotropy of the EPC, we calculated the k-resolved EPC parameters

The values obtained for the unfolded kz = 0 plane of the BZ are presented in Fig. 3b, where one can observe a complex pattern of hot spots (light) and weak-coupling (dark) regions. For a quantitative analysis, we examined the EPC contributions to Γ- and K-centered sheets arising from the two structural layers,

and the corresponding DOS-independent parameters, \({V}^{iD}={\lambda }^{iD}/{N}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}^{iD}\). The computed values of λiD and ViD are collected in Table 1. Since ViD varies from a minimum of 0.30 (\({V}^{{{{{{{\rm{L}}}}}}}_{1}{{{{{\boldsymbol{\Gamma }}}}}}}\)) to a maximum of 0.39 (\({V}^{{{{{{{\rm{L}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\bf{K}}}}}}}\)), we deduce that the layers contribute almost equally to the intrinsic coupling of the various FS pockets. λiD is then determined essentially by the value of the DOS at the Fermi level. We also note that the FS K-cylinder and the layer L2 can be identified as the regions with higher Fermi DOS and EPC in momentum and real space, respectively.

Simulation of the superconducting state

We simulated the superconducting state from first principles using SCDFT48,49,50 with the state-of-the-art SPG functional51. The implementation of the method allowed us to make fully anisotropic calculations of the superconducting gap in both reciprocal and real space52. The k-dependent SCDFT gap equation was solved on a mesh of random k points more densely distributed around the FS for higher accuracy (computational details are provided in Supplementary Note 2 and refs. 47,53). The estimated Tc of 10.2 K, is to be compared with an experimental value \({T}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}}^{\exp }=\) 7.2 K. Given the usual accuracy of SCDFT calculations (within ~20% of Tc), this error is likely to be ascribed to (i) the neglect of anharmonic corrections to the lattice dynamics, that are enhanced close to the CDW transition41, or (ii) limits on the precision in computing phonon properties and dielectric screening imposed by the large size of the CDW cell (see Supplementary Note 2 for an extended discussion). Nevertheless, our prediction is fairly accurate compared to that from conventional Eliashberg theory in the μ* approximation39,54. This, in fact, gives Tc ≃ 16 K under the usual assumption μ* = 0.11, while an exceedingly high value of the Coulomb pseudopotential (μ* = 0.28) is required to reproduce the experimental result. The improved SCDFT estimation of Tc comes from including Coulomb interactions fully ab initio, thus retaining the energy dependence of the screened electron-electron interaction matrix elements \(V\left({\varepsilon }_{n{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}},{\varepsilon }_{n{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}^{\prime} }\right)\). In fact, our simulations show that the electronic states at the Fermi level are poorly screened, that is \(\mu ={N}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}V\left(0,0\right)\) is large. Moreover, because of a different orbital character, these states weakly interact with those far from the Fermi level, yielding a weak reduction of the Coulomb pseudopotential (high μ*)55.

The computed superconducting state turns out to be extremely complex. Unlike MgB2, which has sheet-dependent anisotropy, the superconducting gap in momentum space of NbSe2, Δnk, varies considerably in magnitude both between sheets and within a single sheet. We also note that whereas anisotropic effects in MgB2 enhance Tc56,57,58, that of NbSe2 stays almost constant if anisotropy is washed out. Nevertheless, the degree of gap anisotropy is of essential importance for understanding thermodynamic and spectroscopic properties27,32,34,36,45,59,60,61. Figure 3d shows the histograms of gap values

over the full BZ (green) and the kz = 0 cut of the FS (red). The total distribution reveals a spread of gap values with the main peak at 2.3 meV and several smaller structures at lower values of Δ. While mid- and low-energy features of the curve are well reproduced by the kz = 0 slice of the CDW BZ, the source of the peak can be identified with a hot spot in Δnk at 2/3 of the ML line. The obtained average gap value is of \(\bar{{{\Delta }}}\) = 1.85 meV, corresponding to \(2\bar{{{\Delta }}}/{k}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}{T}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}}\) = 4.3, which is in excellent agreement with experiments59. Our overestimation of Tc naturally leads to an overestimation of the gap. However, multiplying Δ by the factor \({T}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}}^{\exp }/{T}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}}\), the estimated gap is rescaled in between 0.7 and 1.7 meV, which is close to the range seen in Fig. 1b and provided by ARPES measurements33. Figure 3c shows the unfolded gap structure on constant-kz slices of the BZ. We see a complex pattern of superconducting gaps that, like for other anisotropic superconductors62,63,64, mirrors the structure of the EPC (compare the kz = 0 slice with Fig. 3b). In the kz = 0 plane, a high-gap region can be identified with the inner FS sheet of Nb character around the Γ point, while the Fermi arcs at K have, on average, a much smaller superconducting gap. This observation agrees with the inverse correlation between superconducting and CDW gap suggested by ARPES measurements32. Nevertheless, as already mentioned, the FS K-cylinder largely contributes to the superconducting condensation energy due to the overall higher DOS (Table 1) and a significant increase in the gap at large kz (see the slice at \({{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}_{z}=\frac{2}{3}\frac{\pi }{c}\)).

Discussion

For a direct comparison with the experiment, we simulated STM images of bulk NbSe2 by a superconducting Nb tip using the SCDFT gap. Specifically, the superconducting DOS of the sample was computed locally at the tip position from the real-space projection of Eq. (4) (see Supplementary Note 3 for an extended discussion). Figure 5a shows the computational differential-conductance spectra of layer L1, L2 and the full bulk, compared to the experimental spectrum averaged over the sample surface. The tunneling conductance calculated at the points corresponding to the experimental positions in Fig. 1a is also included. The related histograms of gap values are presented in Fig. 5b. Additionally, Fig. 5c provides a real-space image of the superconducting gap from a side view (bottom) and through horizontal cuts on the Nb planes of L1 and L2 (top). Simulations show a strong variation of the tunneling conductance with the scanning position, especially between the layers. Due to the higher DOS at the Fermi level, L2 has, in fact, a much larger average gap (see the high-energy peak in the distribution of gap values). Moreover, a double-peak structure is clearly visible in the differential conductance computed for L2, whereas it almost disappears for L1. Changes in the experimental spectra as a function of the tip position are much less pronounced, and two distinct peaks are always observed (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 4). However, in comparing simulated and experimental spectra, one should consider that the actual CDW is slightly incommensurate, and that the structural patterns on L1 and L2 exist, in fact, on the same surface, smoothly transforming into each other42. This causes an additional degree of hybridization between the electronic states of the two layers, which is not accounted for in the simulations, as it would require using a prohibitively large cell. Additionally, simulations are done in the bulk, thus in absence of surface effects which may influence the gap anisotropy. Nevertheless, by comparing the black and green curves in Fig. 5, we see that the shape of the measured dI/dV tunneling spectrum is, overall, quite well reproduced, especially concerning the positions of the two peaks and the shoulder-like feature at ≈ 3 meV.

a Simulated differential-conductance spectra of NbSe2 for the bulk (green), layer L1 (red), layer L2 (dark blue) and at the experimental positions of Fig. 1a (orange, light blue). Experimental spectrum (black) obtained by averaging over multiple data traces as in Supplementary Fig. 4b. Tunneling currents are computed from the real-space distributions of gap values shown in (b), where Δ is scaled by the factor \({T}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}}^{\exp }/{T}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}}\) to correct for the overestimation of Tc. c Real-space view of the superconducting gap, showing stronger superconductivity on L2, especially at specific Nb sites (bright spots).

We mention that in a recent letter Heil and coworkers65 used ab-initio Migdal–Eliashberg theory to simulate the superconducting properties and tunneling characteristics of NbS2. While the tunneling spectra show strong similarities with those we predict and measure for NbSe2, in the case of NbS2 they are found to originate from a clear two-gap structure. If, on the one hand, these results demonstrate the importance of ab-initio methods for the interpretation of tunneling data, they also show that similar dichalcogenides can hide significantly different superconducting properties. It would be of interest to address this aspect by a detailed comparative ab-initio study.

To summarize, we presented high-resolution STM measurements of the differential conductance of NbSe2 and an ab initio fully anisotropic description of the CDW and superconducting state. The agreement between measured and computed superconducting properties appears to be good. From our analysis emerge the following key aspects: (i) Contrary to the textbook case of MgB2, the gap anisotropy does not influence the stability of the superconducting state, that is perturbations affecting the gap anisotropy are not expected to reduce Tc. (ii) The gap distribution on the FS shows rapid variations with k within each sheet. However, a high-gap structure can be clearly identified as responsible for the main STM coherence peak. Specifically, the peak originates from the same FS sheet that is broken by the occurrence of the CDW, i.e., the FS cylinder centered at the K point. (iii) HC regions of the crystal undergo a strong reduction of the Fermi DOS by the CDW, leading to a lower EPC compared to CC regions (whose Fermi DOS is almost unaffected).

Overall, our simulations indicate that superconducting and CDW orderings in NbSe2 compete in HC regions, whereas superconductivity is not suppressed in CC regions. We rule out, however, a two-gap scenario, providing evidence of strong superconducting gap anisotropy.

Methods

Crystal synthesis and characterization

Bulk crystals of NbSe2 were grown by chemical vapor transport32 and cleaved under ultra-high vacuum. Scanning tunneling microscopy and spectroscopy measurements were performed at 1.1 K with superconducting tips fabricated by indenting a clean NbTi wire into a Nb(111) crystal until the tip’s energy gap reached the bulk value (2Δtip ≈ 3.1 meV). Since the probed signal is a convolution of the DOS of substrate and tip, all the measured spectral features of the sample are shifted by the tip’s energy gap. Additionally, the differential-conductance signal is weighted by the energy-dependent tunneling probability.

Theoretical calculations

We calculated normal-state properties within DFT66,67 using the local density approximation68. Atomic core states were treated in the norm-conserving pseudopotential approach as implemented in the Quantum Espresso code69. Phonon frequencies and EPC were computed by means of density functional perturbation theory70 with an electronic temperature of 270 meV40. Further computational details are given in Supplementary Note 2.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

da Silva Neto, E. H. et al. Ubiquitous interplay between charge ordering and high-temperature superconductivity in cuprates. Science 343, 393–396 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity induced by Se-doping in layered charge-density-wave system 1T−TaS2−xSex. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 192602 (2013).

Li, L. J. et al. Fe-doping-induced superconductivity in the charge-density-wave system 1T−TaS2. EPL 97, 67005 (2012).

Kusmartseva, A. F., Sipos, B., Berger, H., Forró, L. & Tutiš, E. Pressure induced superconductivity in pristine 1T−TiSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 236401 (2009).

Joe, Y. I. et al. Emergence of charge density wave domain walls above the superconducting dome in 1T−TiSe2. Nat. Phys. 10, 421–425 (2014).

Bhoi, D. et al. Interplay of charge density wave and multiband superconductivity in \({2{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}-{{{{{{\rm{Pd}}}}}}}_{x}{{{{{\rm{TaSe}}}}}}}_{2}\). Sci. Rep. 6, 24068 (2016).

Morosan, E. et al. Superconductivity in CuxTiSe2. Nat. Phys. 2, 544–550 (2006).

Dai, P. Antiferromagnetic order and spin dynamics in iron-based superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 855–896 (2015).

Manzeli, S., Ovchinnikov, D., Pasquier, D., Yazyev, O. V. & Kis, A. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17033 (2017).

Chang, J. et al. Direct observation of competition between superconductivity and charge density wave order in YBa2Cu3O6.67. Nat. Phys. 8, 871–876 (2012).

Fujita, M., Goka, H., Yamada, K. & Matsuda, M. Competition between charge- and spin-density-wave order and superconductivity in La1.875Ba0.125−xSrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 167008 (2002).

Gabovich, A. M. et al. Competition of superconductivity and charge density waves in cuprates: recent evidence and interpretation. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2010, 1–40 (2010).

Gabovich, A. M., Voitenko, A. I., Annett, J. F. & Ausloos, M. Charge- and spin-density-wave superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 14, R1–R27 (2001).

Kiss, T. et al. Charge-order-maximized momentum-dependent superconductivity. Nat. Phys. 3, 720–725 (2007).

Xi, X. et al. Strongly enhanced charge-density-wave order in monolayer 2H−NbSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 765–769 (2015).

Cho, K. et al. Using controlled disorder to probe the interplay between charge order and superconductivity in 2H−NbSe2. Nat. Commun. 9, 2796 (2018).

Lian, C.-S., Si, C. & Duan, W. Unveiling charge-density wave, superconductivity, and their competitive nature in two-dimensional 2H−NbSe2. Nano Lett. 18, 2924–2929 (2018).

Zheng, F. & Feng, J. Electron-phonon coupling and the coexistence of superconductivity and charge-density wave in monolayer NbSe2. Phys. Rev. B 99, 161119(R) (2019).

Soumyanarayanan, A. et al. Quantum phase transition from triangular to stripe charge order in NbSe2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 1623–1627 (2013).

Leroux, M. et al. Strong anharmonicity induces quantum melting of charge density wave in 2H−NbSe2 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 92, 140303(R) (2015).

Ugeda, M. M. et al. Characterization of collective ground states in single-layer NbSe2. Nat. Phys. 12, 92–97 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Enhanced superconductivity upon weakening of charge density wave transport in 2H−TaS2 in the two-dimensional limit. Phys. Rev. B 98, 035203 (2018).

Weber, F. et al. Extended phonon collapse and the origin of the charge-density wave in 2H−NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 107403 (2011).

Rossnagel, K. et al. Fermi surface of 2H−NbSe2 and its implications on the charge-density-wave mechanism. Phys. Rev. B 64, 235119 (2001).

Rossnagel, K. On the origin of charge-density waves in select layered transition-metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 23, 213001 (2011).

Malliakas, C. D. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Nb-Nb interactions define the charge density wave structure of 2H−NbSe2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1719–1722 (2013).

Valla, T. et al. Quasiparticle spectra, charge-density waves, superconductivity, and electron-phonon coupling in 2H−NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 086401 (2004).

Johannes, M. D., Mazin, I. I. & Howells, C. A. Fermi-surface nesting and the origin of the charge-density wave in NbSe2. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205102 (2006).

Johannes, M. D. & Mazin, I. I. Fermi surface nesting and the origin of charge density waves in metals. Phys. Rev. B 77, 165135 (2008).

Arguello, C. J. et al. Visualizing the charge density wave transition in 2H−NbSe2 in real space. Phys. Rev. B 89, 235115 (2014).

Zhu, X., Cao, Y., Zhang, J., Plummer, E. & Guo, J. Classification of charge density waves based on their nature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 2367–2371 (2015).

Rahn, D. J. et al. Gaps and kinks in the electronic structure of the superconductor 2H−NbSe2 from angle-resolved photoemission at 1 K. Phys. Rev. B 85, 224532 (2012).

Yokoya, T. et al. Fermi surface sheet-dependent superconductivity in 2H−NbSe2. Science 294, 2518–2520 (2001).

Guillamon, I., Suderow, H., Guinea, F. & Vieira, S. Intrinsic atomic-scale modulations of the superconducting gap of 2H−NbSe2. Phys. Rev. B 77, 134505 (2008).

Noat, Y. et al. Quasiparticle spectra of 2H−NbSe2: two-band superconductivity and the role of tunneling selectivity. Phys. Rev. B 92, 134510 (2015).

Boaknin, E. et al. Heat conduction in the vortex state of NbSe2: evidence for multiband superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 117003 (2003).

McMillan, W. L. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors. Phys. Rev. 167, 331–344 (1968).

Carbotte, J. P. Properties of boson-exchange superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 1027–1157 (1990).

Allen, P. B. & Mitrović, B. Theory of Superconducting Tc, Vol. 37 of Solid State Physics (Academic Press, 1983).

Calandra, M., Mazin, I. I. & Mauri, F. Effect of dimensionality on the charge-density wave in few-layer 2H−NbSe2. Phys. Rev. B 80, 241108(R) (2009).

Bianco, R., Monacelli, L., Calandra, M., Mauri, F. & Errea, I. Weak dimensionality dependence and dominant role of ionic fluctuations in the charge-density-wave transition of NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 106101 (2020).

Gye, G., Oh, E. & Yeom, H. W. Topological landscape of competing charge density waves in 2H−NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 016403 (2019).

Medeiros, P. V. C., Stafström, S. & Björk, J. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic perturbations on the electronic structure of graphene: retaining an effective primitive cell band structure by band unfolding. Phys. Rev. B 89, 041407(R) (2014).

Medeiros, P. V. C., Tsirkin, S. S., Stafström, S. & Björk, J. Unfolding spinor wave functions and expectation values of general operators: introducing the unfolding-density operator. Phys. Rev. B 91, 041116(R) (2015).

Borisenko, S. V. et al. Two energy gaps and Fermi-surface “arcs” in NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 166402 (2009).

Giustino, F. Electron-phonon interactions from first principles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015003 (2017).

Flores-Livas, J. A. et al. A perspective on conventional high-temperature superconductors at high pressure: methods and materials. Phys. Rep. 856, 1–78 (2020).

Oliveira, L. N., Gross, E. K. U. & Kohn, W. Density-functional theory for superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2430–2433 (1988).

Lüders, M. et al. Ab initio theory of superconductivity. I. Density functional formalism and approximate functionals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024545 (2005).

Marques, M. A. L. et al. Ab initio theory of superconductivity. II. Application to elemental metals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024546 (2005).

Sanna, A., Pellegrini, C. & Gross, E. K. U. Combining Eliashberg theory with density functional theory for the accurate prediction of superconducting transition temperatures and gap functions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 057001 (2020).

Linscheid, A., Sanna, A., Floris, A. & Gross, E. K. U. First-principles calculation of the real-space order parameter and condensation energy density in phonon-mediated superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 097002 (2015).

Sanna, A. In The Physics of Correlated Insulators, Metals, and Superconductors Vol. 7 Ch. 16, 429 (eds Pavarini, E., Koch, E., Scalettar, R., & Martin, R.) (Verlag des Forschungszentrum Jülich, 2017).

Scalapino, D. J., Schrieffer, J. R. & Wilkins, J. W. Strong-coupling superconductivity. I. Phys. Rev. 148, 263–279 (1966).

Morel, P. & Anderson, P. W. Calculation of the superconducting state parameters with retarded electron-phonon interaction. Phys. Rev. 125, 1263–1271 (1962).

An, J. M. & Pickett, W. E. Superconductivity of MgB2: covalent bonds driven metallic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4366–4369 (2001).

Floris, A. et al. Superconducting properties of MgB2 from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 037004 (2005).

Putti, M. et al. Intraband vs. interband scattering rate effects in neutron irradiated MgB2. EPL 77, 57005 (2007).

Huang, C. L. et al. Experimental evidence for a two-gap structure of superconducting NbSe2: a specific-heat study in external magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 76, 212504 (2007).

Fletcher, J. D. et al. Penetration depth study of superconducting gap structure of 2H−NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 057003 (2007).

Zehetmayer, M. & Weber, H. W. Experimental evidence for a two-band superconducting state of NbSe2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 82, 014524 (2010).

Sanna, A. et al. Anisotropic gap of superconducting CaC6: a first-principles density functional calculation. Phys. Rev. B 75, 020511(R) (2007).

Floris, A., Sanna, A., Massidda, S. & Gross, E. K. U. Two-band superconductivity in Pb from ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 75, 054508 (2007).

Profeta, G. et al. Superconductivity in lithium, potassium, and aluminum under extreme pressure: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 047003 (2006).

Heil, C. et al. Origin of superconductivity and latent charge density wave in NbS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 087003 (2017).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048–5079 (1981).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Quantum espresso: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support by the European Research Council Advanced Grant FACT (ERC-2017-AdG-788890), the CarESS project, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through grant CRC 183 (project C03), and the European Research Council through the consolidator grant “NanoSpin”.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.R. provided the samples. E.L. and K.J.F. performed the STM characterization and related analysis. A.S and C.P. performed ab-initio simulations and their analysis. A.S., C.P., E.L., K.R., K.J.F., and E.K.U.G. contributed to the discussion and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanna, A., Pellegrini, C., Liebhaber, E. et al. Real-space anisotropy of the superconducting gap in the charge-density wave material 2H-NbSe2. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-021-00412-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-021-00412-8

This article is cited by

-

Electron–phonon physics from first principles using the EPW code

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Precursor region with full phonon softening above the charge-density-wave phase transition in 2H-TaSe2

Nature Communications (2023)