Abstract

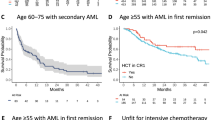

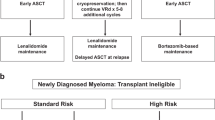

Research into factors affecting treatment response or survival in patients with cancer frequently involves cohorts that span the most common range of clinical outcomes, as such patients are most readily available for study. However, attention has turned to highly unusual patients who have exceptionally favourable or atypically poor responses to treatment and/or overall survival, with the expectation that patients at the extremes may provide insights that could ultimately improve the outcome of individuals with more typical disease trajectories. While clinicians can often recount surprising patients whose clinical journey was very unusual, given known clinical characteristics and prognostic indicators, there is a lack of consensus among researchers on how best to define exceptional patients, and little has been proposed for the optimal design of studies to identify factors that dictate unusual outcome. In this Opinion article, we review different approaches to identifying exceptional patients with cancer and possible study designs to investigate extraordinary clinical outcomes. We discuss pitfalls with finding these rare patients, including challenges associated with accrual of patients across different treatment centres and time periods. We describe recent molecular and immunological factors that have been identified as contributing to unusual patient outcome and make recommendations for future studies on these intriguing patients.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bateson, W. The Methods and Scope of Genetics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1908).

Schwaederle, M. et al. Impact of precision medicine in diverse cancers: a meta-analysis of phase II clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 3817–3825 (2015).

Takebe, N., McShane, L. & Conley, B. Biomarkers: exceptional responders-discovering predictive biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 12, 132–134 (2015).

Weinberg, R. A. The Biology of Cancer 2nd edn (Garland Science, 2014).

Printz, C. NCI launches exceptional responders initiative: researchers will attempt to identify why some patients respond to treatment so much better than others. Cancer 121, 803–804 (2015).

Chang, D. K. et al. Mining the genomes of exceptional responders. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 291–292 (2014).

De La Torre, K. et al. Moonshots and metastatic disease: the need for a multi-faceted approach when studying atypical responses. NPJ Breast Cancer 3, 7 (2017).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Seymour, L. et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 18, e143–e152 (2017).

Rustin, G. J. et al. Definitions for response and progression in ovarian cancer clinical trials incorporating RECIST 1.1 and CA 125 agreed by the Gynecological Cancer Intergroup (GCIG). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 21, 419–423 (2011).

Loaiza-Bonilla, A. et al. Dramatic response to dabrafenib and trametinib combination in a BRAF V600E-mutated cholangiocarcinoma: implementation of a molecular tumour board and next-generation sequencing for personalized medicine. Ecancermedicalscience 8, 479 (2014).

Colton, B. et al. Exceptional response to systemic therapy in advanced metastatic gastric cancer: a case report. Cureus 8, e457 (2016).

Heyman, J. & Leiter, E. Dramatic response of pulmonary metastasis from prostatic cancer to LH-RH agonist treatment. Mt Sinai J. Med. 56, 108–110 (1989).

Iyer, G. et al. Genome sequencing identifies a basis for everolimus sensitivity. Science 338, 221 (2012).

Milowsky, M. I. et al. Phase II study of everolimus in metastatic urothelial cancer. BJU Int. 112, 462–470 (2013).

Cantero, D. et al. Molecular study of long-term survivors of glioblastoma by gene-targeted next-generation sequencing. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 77, 710–716 (2018).

Garsed, D. W. et al. Homologous recombination DNA repair pathway disruption and retinoblastoma protein loss are associated with exceptional survival in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 569–580 (2017).

Jimenez-Sanchez, A. et al. Heterogeneous tumor-immune microenvironments among differentially growing metastases in an ovarian cancer patient. Cell 170, 927–938 (2017).

University of Michigan School of Public Health. Multidisciplinary Ovarian Cancer Outcomes Group. UMich https://sph.umich.edu/mocog/index.html (2018).

Sud, A., Kinnersley, B. & Houlston, R. S. Genome-wide association studies of cancer: current insights and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 692–704 (2017).

Kobel, M. et al. An immunohistochemical algorithm for ovarian carcinoma typing. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 35, 430–441 (2016).

National Cancer Intelligence Network. Overview of Ovarian Cancer in England: Incidence, Mortality and Survival (National Health Service, 2012).

Ma, H., Sun, H. & Sun, X. Survival improvement by decade of patients aged 0–14 years with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a SEER analysis. Sci. Rep. 4, 4227 (2014).

Aletti, G. D. et al. Ovarian cancer surgical resectability: relative impact of disease, patient status, and surgeon. Gynecol. Oncol. 100, 33–37 (2006).

Parachoniak, C. A. et al. Exceptional durable response to everolimus in a patient with biphenotypic breast cancer harboring an STK11 variant. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 3, a000778 (2017).

Wagle, N. et al. Activating mTOR mutations in a patient with an extraordinary response on a phase I trial of everolimus and pazopanib. Cancer Discov. 4, 546–553 (2014).

Ali, S. M. et al. Exceptional response on addition of everolimus to taxane in urothelial carcinoma bearing an NF2 mutation. Eur. Urol. 67, 1195–1196 (2015).

Wagle, N. et al. Response and acquired resistance to everolimus in anaplastic thyroid cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1426–1433 (2014).

Moujaber, T. et al. BRAF mutations in low-grade serous ovarian cancer and response to BRAF inhibition. JCO Precis. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00221 (2018).

McEvoy, C. R. et al. Profound MEK inhibitor response in a cutaneous melanoma harboring a GOLGA4-RAF1 fusion. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 123089 (2019).

Grisham, R. N. et al. Extreme outlier analysis identifies occult mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mutations in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 4099–4105 (2015).

Mehnert, J. M. et al. Immune activation and response to pembrolizumab in POLE-mutant endometrial cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 2334–2340 (2016).

Erson-Omay, E. Z. et al. Somatic POLE mutations cause an ultramutated giant cell high-grade glioma subtype with better prognosis. Neuro Oncol. 17, 1356–1364 (2015).

Stewart, C. J. et al. Long-term survival of patients with mismatch repair protein-deficient, high-stage ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Histopathology 70, 309–313 (2017).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474, 609–615 (2011).

Patch, A.-M. et al. Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature 521, 489–494 (2015).

Levin, M. K. et al. Genomic alterations in DNA repair and chromatin remodeling genes in estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer patients with exceptional responses to capecitabine. Cancer Med. 4, 1289–1293 (2015).

Bolton, K. L. et al. Association between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and survival in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA 307, 382–390 (2012).

Candido-dos-Reis, F. J. et al. Germline mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and ten-year survival for women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 652–657 (2015).

Kotsopoulos, J. et al. Ten-year survival after epithelial ovarian cancer is not associated with BRCA mutation status. Gynecol. Oncol. 140, 42–47 (2016).

Maxwell, K. N. et al. BRCA locus-specific loss of heterozygosity in germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Nat. Commun. 8, 319 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. The BRCA1-delta11q alternative splice isoform bypasses germline mutations and promotes therapeutic resistance to PARP inhibition and cisplatin. Cancer Res. 76, 2778–2790 (2016).

Kondrashova, O. et al. Methylation of all BRCA1 copies predicts response to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 9, 3970 (2018).

Alsop, K. et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 2654–2663 (2012).

Farmer, H. et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005).

Bryant, H. E. et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434, 913–917 (2005).

Necchi, A. et al. Exceptional response to olaparib in BRCA2-altered urothelial carcinoma after PD-L1 inhibitor and chemotherapy failure. Eur. J. Cancer 96, 128–130 (2018).

Lheureux, S. et al. Long-term responders on olaparib maintenance in high-grade serous ovarian cancer: clinical and molecular characterization. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 4086–4094 (2017).

Fridman, W. H. et al. The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 717–734 (2017).

Milne, K. et al. Systematic analysis of immune infiltrates in high-grade serous ovarian cancer reveals CD20, FoxP3 and TIA-1 as positive prognostic factors. PLOS ONE 4, e6412 (2009).

Webb, J. R., Milne, K. & Nelson, B. H. PD-1 and CD103 are widely coexpressed on prognostically favorable intraepithelial CD8 T cells in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 3, 926–935 (2015).

Djenidi, F. et al. CD8+CD103+tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are tumor-specific tissue-resident memory T cells and a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer patients. J. Immunol. 194, 3475–3486 (2015).

Wouters, M. C. A. & Nelson, B. H. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating B cells and plasma cells in human cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 6125–6135 (2018).

Blank, C. U. et al. The “cancer immunogram”. Science 352, 658–660 (2016).

Talhouk, A. et al. Molecular subtype not immune response drives outcomes in endometrial carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3241 (2018).

Chen, D. S. & Mellman, I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature 541, 321–330 (2017).

Lawrence, M. S. et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature 499, 214–218 (2013).

Yarchoan, M., Hopkins, A. & Jaffee, E. M. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2500–2501 (2017).

Le, D. T. et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2509–2520 (2015).

Overman, M. J. et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1182–1191 (2017).

Le, D. T. et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357, 409–413 (2017).

Dunn, I. F. et al. Mismatch repair deficiency in high-grade meningioma: a rare but recurrent event associated with dramatic immune activation and clinical response to PD-1 blockade. JCO Precis. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/po.18.00190 (2018).

Burr, M. L. et al. CMTM6 maintains the expression of PD-L1 and regulates anti-tumour immunity. Nature 549, 101–105 (2017).

Shi, Y. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 67, 1481–1489 (2018).

George, J. et al. Genomic amplification of CD274 (PD-L1) in small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 1220–1226 (2017).

Chong, L. C. et al. Comprehensive characterization of programmed death ligand structural rearrangements in B cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood 128, 1206–1213 (2016).

Bellone, S. et al. Exceptional response to pembrolizumab in a metastatic, chemotherapy/radiation-resistant ovarian cancer patient harboring a PD-L1-genetic rearrangement. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 3282–3291 (2018).

Goodman, A. M. et al. Prevalence of PDL1 amplification and preliminary response to immune checkpoint blockade in solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 4, 1237–1244 (2018).

Green, M. R. et al. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma. Blood 116, 3268–3277 (2010).

Amraee, A. et al. Efficacy of nivolumab as checkpoint inhibitor drug on survival rate of patients with relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis of prospective clinical study. Clin. Transl Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-018-02032-4 (2019).

Miao, D. et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science 359, 801–806 (2018).

Jelinic, P. et al. Recurrent SMARCA4 mutations in small cell carcinoma of the ovary. Nat. Genet. 46, 424–426 (2014).

Jelinic, P. et al. Immune-active microenvironment in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type: rationale for immune checkpoint blockade. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 110, 787–790 (2018).

Gadducci, A. & Guerrieri, M. E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in gynecological cancers: update of literature and perspectives of clinical research. Anticancer Res. 37, 5955–5965 (2017).

Wiegand, K. C. et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1532–1543 (2010).

Champiat, S. et al. Hyperprogressive disease is a new pattern of progression in cancer patients treated by anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 1920–1928 (2017).

Kato, S. et al. Hyperprogressors after immunotherapy: analysis of genomic alterations associated with accelerated growth rate. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 4242–4250 (2017).

Lo Russo, G. et al. Antibody-Fc/FcR interaction on macrophages as a mechanism for hyperprogressive disease in non-small cell lung cancer subsequent to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 989–999 (2019).

Tran, E. et al. Cancer immunotherapy based on mutation-specific CD4+T cells in a patient with epithelial cancer. Science 344, 641–645 (2014).

Zacharakis, N. et al. Immune recognition of somatic mutations leading to complete durable regression in metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Med. 24, 724–730 (2018).

Maude, S. L. et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 439–448 (2018).

Park, J. H. et al. Long-term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 449–459 (2018).

Mellman, I., Coukos, G. & Dranoff, G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 480, 480–489 (2011).

Sadelain, M., Riviere, I. & Riddell, S. Therapeutic T cell engineering. Nature 545, 423–431 (2017).

June, C. H. & Sadelain, M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 64–73 (2018).

Fraietta, J. A. et al. Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19-targeted T cells. Nature 558, 307–312 (2018).

Meyerhardt, J. A. et al. Dietary glycemic load and cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 104, 1702–1711 (2012).

Park, S. Y. et al. High-quality diets associate with reduced risk of colorectal cancer: analyses of diet quality indexes in the multiethnic cohort. Gastroenterology 153, 386–394 (2017).

Beasley, J. M. et al. Meeting the physical activity guidelines and survival after breast cancer: findings from the after breast cancer pooling project. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 131, 637–643 (2012).

Campbell, P. T. et al. Associations of recreational physical activity and leisure time spent sitting with colorectal cancer survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 876–885 (2013).

Cannioto, R. A. et al. Recreational physical inactivity and mortality in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: evidence from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Br. J. Cancer 115, 95–101 (2016).

Nagle, C. M. et al. Obesity and survival among women with ovarian cancer: results from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Br. J. Cancer 113, 817–826 (2015).

Nunez, C. et al. Physical activity, obesity and sedentary behaviour and the risks of colon and rectal cancers in the 45 and up study. BMC Public Health 18, 325 (2018).

Chan, J. A. et al. Hormone replacement therapy and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 5680–5686 (2006).

Symer, M. M. et al. Hormone replacement therapy and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 17, e281–e288 (2018).

Eeles, R. A. et al. Adjuvant hormone therapy may improve survival in epithelial ovarian cancer: results of the AHT randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 4138–4144 (2015).

Phipps, A. I. et al. Associations between cigarette smoking status and colon cancer prognosis among participants in North Central Cancer Treatment Group phase III trial N0147. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 2016–2023 (2013).

Praestegaard, C. et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with adverse survival among women with ovarian cancer: results from a pooled analysis of 19 studies. Int. J. Cancer 140, 2422–2435 (2017).

Jayasekara, H. et al. Associations of alcohol intake, smoking, physical activity and obesity with survival following colorectal cancer diagnosis by stage, anatomic site and tumor molecular subtype. Int. J. Cancer 142, 238–250 (2018).

Molina, Y. et al. Resilience among patients across the cancer continuum: diverse perspectives. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 18, 93–101 (2014).

Strauss, B. et al. The influence of resilience on fatigue in cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy (RT). J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 133, 511–518 (2007).

Wenzel, L. B. et al. Resilience, reflection, and residual stress in ovarian cancer survivorship: a gynecologic oncology group study. Psychooncology 11, 142–153 (2002).

Pearce, C. L. et al. Combined and interactive effects of environmental and GWAS-identified risk factors in ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 880–890 (2013).

Harvard Medical School Department of Biomedical Informatics. Network of Enigmatic Exceptional Responders (NEER) study. People-Powered Medicine https://peoplepoweredmedicine.org/neer (2018).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02243592 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02701907 (2018).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03740503 (2018).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02321735 (2016).

Acknowledgements

F.A.M.S. is supported by a Swiss National Foundation Early Postdoc Mobility Fellowship (P2BEP3-172246), Swiss Cancer Research Foundation grant BIL KFS-3942-08-2016 and a Professor Dr Max Cloëtta and Uniscientia Foundation grant. B.H.N., A.dF., C.L.P., M.C.P., D.W.G. and D.D.L.B. are supported by US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command grant W81XWH-16-2-0010. D.D.L.B. is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) grants APP1092856 and APP1117044 and by the US National Cancer Institute U54 programme (U54CA209978). The authors acknowledge additional support from Margaret Rose AM and the Rose family, The WeirAnderson Foundation, Border Ovarian Cancer Awareness Group, donors to the Garvan Institute of Medical Research Ovarian Cancer Research Program, the Peter MacCallum Cancer Foundation, Wendy Taylor and Arthur Coombs and family. The Australian Ovarian Cancer Study (AOCS) was supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under DAMD17-01-1-0729.

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Cancer thanks A. Biankin, S. Percy Ivy and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A.M.S., D.W.G. and D.D.L.B. wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures. B.H.N. wrote the section on immunology, and C.L.P. wrote the section on epidemiology. F.A.M.S., A.P. and M.C.P. performed data analyses for the article. A.H., A.dF., E.L.G., S.J.R., J.A.B., S.F., A.B., S.L., P.D.P. and M.C.P. provided a substantial contribution to discussions of the content. D.W.G. and D.D.L.B. contributed equally to supervision of the project. All authors contributed to the review and editing of the article before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program: http://www.seer.cancer.gov

Glossary

- Complete response

-

(CR). The disappearance of all target lesions in response to treatment.

- Genome-wide association studies

-

(GWAS). Studies that compare genetic markers across the genome in individuals with and without disease traits.

- Hyper-progression

-

Accelerated disease progression associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

- Hypomorphic germline alleles

-

Also called hypomorphic mutations; inherited genetic variants that cause partial (not complete) loss of gene function through reduced expression or function.

- Maintenance therapy

-

Treatment provided following initial therapy to prevent relapse.

- Multivariable analyses

-

Statistical models taking into account the impact of multiple explanatory variables that may influence a single outcome.

- Partial response

-

(PR). A decrease of at least 30% in the sum of the diameters of target lesions in response to treatment.

- Polygenic risk

-

A genetic susceptibility score based on the combination of multiple, often low-penetrance, disease susceptibility alleles.

- Synthetic lethality

-

A phenomenon in cells or organisms whereby two gene or pathway defects occurring in isolation have little or no effect on survival but for which the combination of both leads to death.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saner, F.A.M., Herschtal, A., Nelson, B.H. et al. Going to extremes: determinants of extraordinary response and survival in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 19, 339–348 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0145-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0145-5

This article is cited by

-

Beating the odds: molecular characteristics of long-term survivors of ovarian cancer

Nature Genetics (2022)

-

The genomic and immune landscape of long-term survivors of high-grade serous ovarian cancer

Nature Genetics (2022)

-

Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in cancer patients with COVID-19

Frontiers of Medicine (2021)