Abstract

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are a burdensome condition due to potential surgical requirements and increased risk of long term debilitation. Previous studies indicate that muscle forces play an important role in the development of ligamentous loading, yet these studies have typically used cadaveric models considering only the knee-spanning quadriceps, hamstrings and gastrocnemius muscle groups. Using a musculoskeletal modelling approach, we investigated how lower-limb muscles produce and oppose key tibiofemoral reaction forces and moments during the weight acceptance phase of unanticipated sidestep cutting. Muscles capable of opposing (or controlling the magnitude of) the anterior shear force and the external valgus moment at the knee are thought to be have the greatest potential for protecting the anterior cruciate ligament from injury. We found the best muscles for generating posterior shear to be the soleus, biceps femoris long head and medial hamstrings, providing up to 173N, 111N and 77N of force directly opposing the anterior shear force. The valgus moment was primarily opposed by the gluteus medius, gluteus maximus and piriformis, with these muscles providing contributions of up to 32 Nm, 19 Nm and 21 Nm towards a knee varus moment, respectively. Our findings highlight key muscle targets for ACL preventative and rehabilitative interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury is a burdensome condition due to potential surgical requirements, substantial convalescence and rehabilitation time1, and associated financial costs to individuals and the healthcare system2. ACL injury has also been shown to be associated with an increased risk of early onset knee osteoarthritis, especially if accompanied by meniscal injury3. Consequently, knowledge regarding the mechanical factors related to ACL injury and injury risk are needed to develop effective prophylactic strategies.

Whilst the primary role of the ACL is to resist anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur4, both cadaveric and modelling studies have shown that frontal and transverse plane knee mechanics can also influence ACL loading5,6,7,8. In the frontal plane, a greater ‘external’ knee valgus or varus moment has the potential to increase load on the ACL5,8. However, knee valgus has been reported to be the more common mechanism of injury in video analysis studies9,10,11. In the transverse plane, an ‘external’ moment causing internal rotation of the tibia with respect to the femur has been found to expose the ACL to higher loads than an ‘external’ moment causing external rotation of the tibia with respect to the femur5,8. Moreover, non-sagittal plane knee joint moments have been shown to have the greatest influence on ACL loading when they occur simultaneously and especially in conjunction with an anterior shear force5,7,8,12. A better understanding regarding the development of these critical knee joint loads could therefore be beneficial for improving ACL preventative and rehabilitative strategies.

Muscles produce forces that can cause and oppose these critical knee joint loads. For example, the quadriceps generates an anterior tibiofemoral shear force which is directly opposed by the ACL13. In contrast, the hamstrings have the potential to mitigate anterior tibiofemoral shear forces thereby working with the ACL to control the amount of anterior translation at the knee joint13,14. Despite the amount of research completed to date, existing knowledge regarding biomechanical variables associated with high loading of the ACL is still quite limited. No studies have investigated which muscles contribute most substantially towards critical knee joint loads during high injury risk tasks such as unanticipated cutting. Furthermore, through “dynamic coupling”, any muscle in the body can potentially induce an acceleration of any segment in the body15. For example, it is possible that certain hip muscles can influence knee joint loads during rapid change in direction tasks. Ignoring the role of the hip muscles may mean that some valuable information that could be used to guide preventative and rehabilitative interventions has been overlooked.

Musculoskeletal modelling enables the cause-effect relationships between muscle forces and joint loads during high injury risk tasks to be evaluated16. Subsequently, the purpose of this study was to investigate the role of the major lower-limb muscles on key tibiofemoral loading parameters associated with ACL injury during an unanticipated sidestep cut. Specifically, we used a computational musculoskeletal modelling approach to predict lower-limb muscle contributions to the knee joint anteroposterior shear force as well as the frontal and transverse plane moments. Our primary interest was to identify which muscles have the greatest capacity to control/minimise the anterior shear force as well as the knee valgus and internal rotation moments, as the function of such muscles could then be targeted in ACL prevention programs.

Methods

Participants

Eight recreationally active healthy males (age: 27 ± 3.8 years; height: 1.77 ± 0.09 m; mass: 77.6 ± 12.8 kg) volunteered to participate in this study. All participants had no current or previous musculoskeletal injury likely to influence their ability to perform the required tasks. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Ethical approval was granted by the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2015-11 H), and the study was carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Instrumentation

Three-dimensional marker trajectories were collected at 200 Hz using a nine camera motion analysis system (VICON, Oxford Metrics Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom). Ground reaction forces were collected via two AMTI OR6-6-2000 ground-embedded force plates (Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA) sampling at 1000 Hz. Surface electromyographic (EMG) data were collected at 1000 Hz from 10 lower-limb muscles on the dominant leg (defined as the kicking leg; right side for all participants) via two wireless EMG systems (Noraxon, Arizona, USA; Myon, Schwarzenberg, Switzerland).

Procedures

All participants were barefoot during the completion of all tasks, which allowed exposure of the foot for marker placement and kept the foot-ground interaction consistent across all participants. The skin was prepared for surface EMG collection by shaving, abrasion and sterilisation. Circular bipolar pre-gelled Ag/AgCl electrodes (inter-electrode distance of 2 cm) were then placed on the vastus lateralis and medialis, rectus femoris, biceps femoris, medial hamstrings, medial and lateral gastrocnemius, soleus, tibialis anterior and peroneus longus muscles in accordance with Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscle (SENIAM) guidelines17. EMG-time traces during forceful isometric contractions were visually inspected to verify the correct placement of the electrodes and to inspect for cross-talk. Forty-three 14 mm retroreflective markers were affixed to various anatomical locations on the torso (sternum, the spinous process of the 7th cervical vertebra, the spinous process of a mid-thoracic vertebra, the tip of each acromion), pelvis (anterior and posterior superior iliac spines), upper-limbs (medial and lateral elbow and distal radius and ulna) and lower-limbs (medial and lateral femoral epicondyles, medial and lateral malleoli, first and fifth metatarsophalangeal joints, calcaneus and three additional markers on each shank and thigh) of each participant.

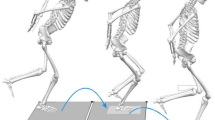

Each participant completed two unanticipated change of direction tasks on their dominant leg. Participants were required to perform two single leg hops for a standardised distance of 1.35 m, and then as quickly as possible cut to the left (45° sidestep cut) or to the right (45° crossover cut) upon landing from the second hop. We used a hopping approach based on prior research18 because it allows speed and foot placement on the force plate to be well controlled across participants relative to a running approach. The direction of travel was randomly dictated by a set of timing gates that delivered a light signal ~450 ms prior to initial contact on the force plates. Floor markings were used to indicate the starting point, the hop landing targets and the required 45° angle from the force plates for the cutting direction. A successful trial required that the participant completed the task correctly with the entire foot landing within the force plate. This protocol produced approach velocities (2.24 ± 0.15 m/s) and cutting angles (41 ± 2°) that were consistent with characteristics reported during ACL injuries19. Note that we only analysed sidestep cuts in this investigation, as this task has been most commonly associated with injury to the ACL9,10,19,20.

Data processing

Marker trajectories were low-pass filtered using a zero-lag, 4th order Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 8 Hz. This cut-off frequency was determined via a residual analysis. Ground reaction forces were filtered using the same filter and cut-off frequency as the marker data based on published recommendations21. EMG data were corrected for offset, high-pass filtered (20 Hz), full-wave rectified and low-pass filtered (6 Hz) using a zero-lag, 4th order Butterworth filter to obtain a linear envelope. EMG data were normalised to the peak amplitude obtained in each trial.

Musculoskeletal modelling

A 37 degree-of-freedom (DOF) full-body musculoskeletal model, with 80 musculotendon actuators (lower body) and 17 torque actuators (upper body)22, was used to perform the musculoskeletal simulations in OpenSim16. Each hip was modelled as a 3-DOF ball and socket. Each knee was modelled as a 1-DOF hinge, with other rotational (valgus/varus and internal/external rotation) and translational (anteroposterior and superior-inferior) movements constrained to change as a function of the knee flexion angle23. A pin joint was used to represent the ankle (talocrural) joint. The head-trunk segment was modelled as a single rigid segment, articulating with the pelvis via a 3-DOF ball and socket joint. Each upper limb was characterised by a 3-DOF ball and socket shoulder joint and single-DOF elbow and radioulnar joints. The subtalar, metatarsophalangeal, and wrist joints were locked22. The generic model was scaled to each participant’s individual anthropometry as determined during a static trial. An inverse kinematics algorithm was used to calculate joint angles by means of a weighted least-squares optimisation that minimised the difference between model and experimental marker positions24. Inverse dynamics was used to obtain the joint moments acting about each modelled DOF. Muscle forces were obtained via a static optimisation algorithm, which decomposed the joint moments into individual muscle forces by minimising the sum of muscle activations squared, taking into account the physiological force-length-velocity properties25 of the musculotendinous units. This method of muscle force estimation is computationally efficient and has been used to predict muscle forces in similar high impact movements26,27,28. Note that the maximum isometric force of each actuator was increased 3-fold from the standard model, similar to another study that investigated high impact manoeuvres26.

The measured ground reaction forces were decomposed into individual muscular contributions by means of a pseudo-inverse-based approach28,29,30. Each muscle’s contribution to the joint reaction forces and moments about the knee were then computed by applying each muscle’s force and contribution to the ground reaction force in isolation and resolving the dynamical equations of motion. The knee joint reaction forces and moments represent the forces and moments that the knee joint experiences as a consequence of all motions and forces in the model, including muscles and other actuators. These parameters differ somewhat from the inverse dynamics based outputs used with the static optimisation algorithm to calculate muscle forces.

Outcome variables

Outcome variables of interest were each muscle’s contribution to the tibiofemoral anteroposterior shear joint reaction force as well as the frontal and transverse plane joint reaction moments, as these variables have been shown to be associated with higher ACL loads and/or injury5,6. Since ACL injuries occur promptly after initial contact9, we limited our analysis to the weight acceptance phase (period of stance from foot-strike to the first trough in the raw vertical ground reaction force) as per previous research31,32. Muscular contributions were grouped according to function consistent with a prior approach33, except where these muscles had opposing effects on the key tibiofemoral loading parameters. For example, the biceps femoris long head and medial hamstrings (i.e. semimembranosus and semitendinosus) have opposing transverse plane actions at the knee, hence the biarticular hamstrings were not grouped together (see Supplementary Table S1 for all functional groupings). Note that we only report on major muscle groups, and did not report on any muscle that was not found to make a meaningful contribution to any of the three key knee reaction forces or moments (see Rajagopal et al.22 for all musculotendinous actuators included in the model).

Validation and verification

To provide confidence in our simulations, we performed qualitative comparisons between the model-based predicted activations and experimental EMG data, accounting for appropriate physiological delays (~100ms) as per current recommendations34. We obtained EMG data from experimental recordings conducted in the present study and from available data in the literature35,36. Since these comparisons were conducted to assess how well the simulation replicated the coordination pattern observed experimentally, the normalised EMG data were averaged across participants and then renormalised to the peak amplitude of each muscle. The predicted activations were processed using the same normalisation procedure as the EMG data, prior to these comparisons. We also compared the time-varying characteristics of our experimental joint angles and inverse dynamics based joint moments (Fig. 1) to ensure they were within 2 SD of prior published data34. These qualitative comparisons were conducted across the entire stance phase because the weight acceptance phase was generally too short to allow any firm conclusions to be made about how well our model-based predicted data temporally matched experimental data as well as data obtained from the literature.

We quantitatively verified that our muscle-derived joint moments (computed from the predicted muscle forces and their respective moment arms) matched the experimentally measured joint moments (computed via inverse dynamics) by calculating the normalised root-mean-square error (nRMSE) and coefficient of determination (R2). The nRMSE was calculated as:

To verify the suitability of the foot-ground contact model, superposition errors between experimental and simulated ground reaction forces were quantitatively evaluated via computation of the nRMSE and R2. These data were reported as the median and interquartile range (IQR) due to non-normal distributions.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Validation

Muscle-derived joint moments showed excellent agreement with inverse dynamics based joint moments (R2, 1.0, IQR, 1.0 to 1.0; nRMSE, 3.2 × 10−3%, IQR, 1.5 × 10−3 to 1.1 × 10−2%; Fig. 1). The foot-ground contact model also showed acceptable results, with model-predicted ground reaction forces in agreement with experimentally measured ground reaction forces (R2, 0.95, IQR, 0.92 to 0.97; nRMSE, 7.9%, IQR, 6.1 to 10%). Additionally, once appropriate physiological delays were taken into account (100 ms corresponds to ~25% of stance phase), reasonable agreement was evident between the predicted muscle activations from the model and experimentally recorded EMG data obtained from the current study as well as prior literature (Fig. 2).

Comparison of predicted (black line) and experimental activations (grey shaded) from the current data during the stance phase of the 45° unanticipated sidestep cut. Literature reference activations, magenta dashed line, Neptune et al.35; blue dotted line, Beaulieu et al.36. BFLH, biceps femoris long head; MEDHAM, medial hamstrings (semitendinosus and semimembranosus); VASMED, vastus medialis; VASLAT, vastus lateralis; RECFEM, rectus femoris; SOLEUS, soleus; GASMED, gastrocnemius medialis; GASLAT, gastrocnemius lateralis; TIBANT, tibialis anterior; PERLONG, peroneus longus; ADDMAG, adductor magnus; GMAX, gluteus maximus; GMED, gluteus medius.

Anteroposterior shear joint reaction force

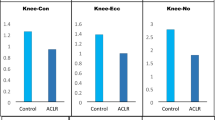

The net anteroposterior shear force was characterised by an anterior shear force of 218 N at initial contact, which gradually declined until switching to a posterior shear force at 46% of the weight acceptance phase (Fig. 3A and B). The greatest contributors to the posterior shear force were the biarticular hamstrings and soleus. The contribution of each of these muscles increased throughout weight acceptance, peaking at 173N, 111N, and 77N for the soleus, biceps femoris long head and medial hamstrings, respectively. The anterior shear force was primarily produced by the quadriceps and gastrocnemius muscle groups. The vasti’s contribution increased throughout weight acceptance, peaking at 225N, whilst contributions from the rectus femoris and lateral gastrocnemius peaked at initial contact at 83N and 38N, respectively. The medial gastrocnemius peaked at 84N at 5% of weight acceptance, and remained at around 60N for the majority of the remainder weight acceptance. The non-knee-spanning ankle dorsi-flexors (tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum and hallucis longus), adductors and gluteus maximus also contributed 50–60N during mid-weight acceptance. The shift to a net posterior shear force at 46% of weight acceptance was mainly explained by a decline in the contribution from the gastrocnemius towards anterior shear, and an increase in the contribution from the biarticular hamstrings and soleus towards posterior shear.

Muscular contributions to knee anteroposterior shear joint reaction force (row 1), frontal plane knee joint reaction varus/valgus moment (row 2) and transverse plane knee joint reaction internal/external rotation moment (row 3) during the weight acceptance phase of the 45° unanticipated sidestep cut. The first column (panels A, C and E) show knee-spanning muscles, the second column (panels B, D, and F) show non-knee-spanning muscles. Note that the shaded grey represents the experimental value (net value accounting for all forces) for each reaction load. BFLH, biceps femoris long head; BFSH, biceps femoris short head; GASLAT, gastrocnemius lateralis; GASMED, gastrocnemius medialis; MEDHAM, medial hamstrings (semitendinosus and semimembranosus); RECFEM, rectus femoris; VASTI, vasti; ADD, adductors (adductor brevis, longus and magnus); DORSI, dorsiflexors (tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum and hallucis longus), GMAX, gluteus maximus; GMED, gluteus medius; GMIN, gluteus minimus; ILIOPSOAS, iliopsoas (iliacus and psoas major); PIRI, piriformis; SOLEUS, soleus.

Frontal plane joint reaction moment (varus/valgus)

A varus knee joint reaction moment (peak of 25 Nm) was present for the first 72% of weight acceptance, whereas a valgus knee joint reaction moment (peak of 12 Nm) was present for the remaining portion (Fig. 3C and D). Throughout weight acceptance, the gluteal muscles had the greatest capacity to oppose the valgus moment. The gluteus medius produced the largest varus moment (ranging from 23–32 Nm across weight acceptance). Substantial contributions were also made by the piriformis (7–21 Nm) and gluteus maximus (9–19 Nm). The transition to a valgus knee joint reaction moment was driven by decreasing contributions from the gluteals, piriformis and adductors towards a varus moment, and increasing contributions from the vasti (up to 31 Nm), soleus (up to 10 Nm) and biceps femoris long head (up to 4 Nm) towards a valgus moment.

Transverse plane joint reaction moment (internal/external rotation)

An external rotation knee joint reaction moment was present throughout the entire weight acceptance period (Fig. 3E and F). The external rotation moment was 1–2 Nm for the first quarter of weight acceptance. It progressively increased during the second half of weight acceptance, peaking at 25 Nm. The dominant contributors towards this moment were the vasti (up to 23 Nm) and soleus (up to 10 Nm) muscles. The gluteus maximus (2–10 Nm) and gluteus medius (4–5 Nm) muscles had the greatest potential to oppose this moment (i.e. contribute to an internal rotation knee joint reaction moment) throughout weight acceptance.

Discussion

This study has shown that both knee-spanning and non-knee-spanning muscles contribute to the tibiofemoral reaction forces and moments during the weight acceptance phase of a rapid unanticipated sidestep cut. Notably, we found the biarticular hamstrings and the soleus muscles to have the greatest potential to oppose the anterior shear reaction force, whilst the hip abductors (gluteus medius, gluteus maximus and piriformis) had the greatest potential to oppose the knee valgus reaction moment. To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have calculated muscular contributions to knee joint loads during a rapid unanticipated sidestep cut.

The data reported in the present paper are largely consistent with prior literature. Experimental kinematics (Fig. 1, top row) and inverse dynamics based joint moments (Fig. 1, bottom row) were within 2 SD of prior research investigating similar cutting tasks18,37,38. Additionally, the predicted muscle activations showed reasonable agreement with EMG data for sidestep cutting obtained from the current study and the literature35,36. Whilst this consistency provides some evidence that our simulations were physiologically acceptable, the main focus of the present study concerned muscular contributions to the tibiofemoral anteroposterior shear reaction force as well as the frontal and transverse plane joint reaction moments. To our knowledge, only one study by Sritharan and colleagues33 has reported comparable data. They computed the muscular contributions to the ‘external’ knee varus moment during gait. Note that Sritharan et al.33 quantified the muscular contributions to the inverse dynamics based joint moments, rather than the joint reaction forces/moments as we have reported here. Additionally, they did not include all of the muscles we have evaluated in the present study. Finally, they investigated walking, which has quite different biomechanical demands to sidestep cutting. Nevertheless, some consistent functional roles for key muscles are evident when comparing data from Sritharan et al.33 with equivalent data from the present study. For example, we observed that the gluteal muscle group had the greatest potential to generate a varus knee joint reaction moment during the weight acceptance phase of sidestep cutting, i.e. these muscles opposed the net valgus knee joint reaction moment that occurred during the final 25% of weight acceptance (Fig. 3D). Similarly, Sritharan et al.33 found that the gluteus medius and maximus muscles were the major contributors to the ‘external’ knee varus moment during the stance phase of walking. They also found that the vasti and soleus were dominant contributors towards an ‘external’ knee valgus moment, which is consistent with the findings from the current study for cutting (Fig. 3C and D).

Anteroposterior shear joint reaction force

The primary role of the ACL is to resist anterior tibial translation4, and thus tibiofemoral shear has received much attention in the literature5,6,7. The quadriceps and hamstring muscle groups are of particular interest in this respect due to their ability to induce anterior and posterior shear forces, respectively39. We found that the vasti and biarticular hamstrings were indeed major contributors to anterior and posterior shear forces, respectively. However, our analysis provided insight into the critical role of other muscles, particularly the gastrocnemius and soleus, which appeared to have considerable yet opposing roles in the development of tibiofemoral shear force (Fig. 3A and B). The opposing roles of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles has been observed in previous research investigating contributions to trunk and leg segmental energy40 as well as whole body sagittal plane angular momentum during gait41. We have shown that the soleus tends to induce posterior shear reaction forces, whilst the gastrocnemius tends to induce anterior shear reaction forces at the tibiofemoral joint. Our results therefore suggest that the soleus and gastrocnemius represent ACL agonists and antagonists, respectively; an observation that is consistent with prior musculoskeletal modelling27,42 and in-vivo studies43. In contrast to these findings, Morgan and colleagues31 reported that the gastrocnemius plays a role in unloading the ACL by increasing joint compression and thereby resisting tibial translation44. However, this assertion was based on a hypothetical explanation of elevated gastrocnemius forces observed in participants with low versus high estimated ACL loading. The role of joint compression is contentious, as animal models have shown that whilst joint compression may act to reduce anteroposterior translation, the direct influence on ACL loading may still be hazardous45. Nevertheless, we accept that muscular contributions to knee joint compression could have potential implications for ACL loading, thus we have computed these values for completeness and have included the results as supplementary material for the interested reader (see Supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, knee joint anterior shear force has consistently been associated with ACL loading5,7,46,47,48,49, thus our cause-effect analysis showing that the gastrocnemius group induces anterior shear forces would suggest that the role of the gastrocnemius on its own is unlikely to be “protective”.

Frontal and transverse plane joint reaction moments

One of the most noteworthy findings in this study is that the gluteal muscle group is capable of generating a varus knee joint reaction moment, thus opposing (or controlling the magnitude of) the net valgus knee joint reaction moment during the final 25% of weight acceptance of sidestep cutting. The gluteus medius provided the greatest contribution to the varus knee joint reaction moment for the entire weight acceptance phase, whilst other muscles (piriformis and gluteus maximus and minimus) also made appreciable contributions (Fig. 3D). This result has implications for preventative and rehabilitative interventions, as both knee valgus loading50 and lower hip abduction strength51 have been prospectively associated with ACL injury. Additionally, knee valgus loading has been observed during ACL injuries9,10,11, and has been directly related to ACL loading5,7,8. The gluteal muscles were also found to be the primary contributors to the internal rotation knee joint reaction moment (Fig. 3F), which potentially increases loads on the ACL5,7,12. However, the size of this contribution was relatively small (<10 Nm), and the tibiofemoral joint never experienced a net internal rotation reaction moment at any stage during the weight acceptance phase (Fig. 3E and F). As sidestep cutting is typically associated with valgus loading32, which is thought to be particularly relevant for non-contact injury mechanisms9,20, the function of the gluteal muscle group may be an important target for prevention programs aiming to reduce ACL injury risk. To our knowledge, no other study has demonstrated the importance of the gluteus medius (or the other hip abductor muscles) for opposing the knee valgus moment that occurs during sidestep cutting.

Simultaneous multi-direction loading

It is thought that loads on the ACL are greatest when the knee joint is exposed to an anterior shear force together with a valgus and an internal rotation moment5,7,46. Whilst this specific combination of tibiofemoral reaction forces and moments was not observed to occur simultaneously in our data (Fig. 3), muscular contributions must still be considered across multiple planes due to their potential to cause or oppose relevant joint reaction forces and moments. Whilst a valgus moment that occurs together with an internal rotation moment has the potential to increase load on the ACL5,7,8,12, none of the major contributors to a valgus knee joint reaction moment were also found to be major contributors to an internal rotation knee joint reaction moment (Fig. 3C–F). The relative importance of non-sagittal loads to ACL loading is not universally accepted52, whereas anterior and posterior shear force have been consistently shown to load and unload the ACL, respectively5,6,7,46,47,48,49. Subsequently, appropriate muscular targets for interventions should be chosen primarily based on the magnitude of their contributions to anteroposterior shear force, with contributions to non-sagittal plane joint reaction moments perhaps a secondary consideration.

Key clinical implications

Based on the findings from this study, we suggest that injury prevention strategies should focus on optimising the function of the hamstring muscle group, as the biceps femoris long head and medial hamstrings were shown to be the two primary contributors to posterior shear during weight acceptance of sidestep cutting (Fig. 3A). Additionally, these muscles induce opposite loading patterns in the frontal (Fig. 3C) and transverse planes (Fig. 3E), thus reducing the likelihood for combined unfavourable loading patterns to be generated. The function of the soleus would also seem important, due to this muscle’s contribution to the posterior shear knee joint reaction force (Fig. 3B), whilst also contributing to an external rotation knee joint reaction moment (Fig. 3F). However, from a practical standpoint, the function of the soleus may be difficult to isolate from the gastrocnemius, a muscle group which we found to contribute to an anterior shear reaction force at the knee. Finally, the gluteal group, especially the gluteus medius and the piriformis muscles, were the dominant controllers of the valgus knee joint reaction moment (Fig. 3D), and also made no meaningful contribution towards anterior shear and their contribution towards an internal rotation knee joint reaction moment was minimal. For these reasons, we consider training the function of the gluteus medius and piriformis muscles to be of high priority in ACL prevention programs.

Limitations

Whilst our study has revealed some novel insights, we acknowledge that there are some limitations to this work. One limitation is that the present study only involved a cohort of eight healthy recreationally active males. Further research should consider the influence of different populations such as females, specific athletic subgroups, and pathological populations. Additionally, participants were barefoot during the performance of the sidestep cut, which is not representative of many sports that involve footwear. There is the possibility that this may have resulted in an imposed foot-strike pattern for some participants, and a natural foot-strike pattern for others53. However, we do not believe this influenced the conclusions of the study. The advantage of the barefoot condition was that it ensured a consistent foot-ground interaction across participants, and allowed exposure of the foot for marker placement.

Another limitation is that we did not compute ACL forces directly. Whilst including knee ligaments into the musculoskeletal model would have allowed us to predict ligament (or ACL) forces directly, this complexity would come at the cost of introducing additional uncertainties related to in-vivo ligament properties54. Due to the sensitivity of estimated ACL forces to these ligament properties (e.g. reference strains and ligament stiffness)54, we opted to exclude ligaments from the model.

The decision to exclude ligaments from the model meant that translations and non-sagittal rotations at the knee needed to be constrained as a function of the knee flexion angle23, similar to prior studies27, in order to ensure our predicted muscle forces were as accurate as possible. Another advantage of adopting such constraints is minimising the impact of soft tissue artefact. Prior research has shown that non-sagittal plane knee rotations are particularly sensitive to soft tissue artefact when using skin-mounted marker systems18. Whilst soft tissue artefact can influence all joint angles, we used a global optimisation inverse kinematics algorithm to obtain our joint angle data, which has previously been shown to be capable of minimising the influence of soft tissue artefact24. We note that our kinematic data are consistent with prior literature investigating similar change of direction tasks using both skin-mounted37,38 and bone-pin marker systems18.

Muscle forces in the present study were estimated using a static optimisation algorithm, which does have some limitations. Unfortunately, muscle forces cannot be directly validated, as in-vivo muscle forces are not practically feasible to measure55, thus we have no way of directly validating our model predictions. Static optimisation has been shown to provide accurate predictions of in-vivo joint contact forces56,57, which serves as an indirect validation of muscle forces due to the high dependency of joint contact forces on muscle forces55. Furthermore, our predicted muscle activations showed reasonable agreement with experimentally recorded EMG data across the stance phase (Fig. 2). It has been suggested that static optimisation may not adequately predict co-contraction of muscles. However, our predicted muscle activations (Fig. 2) as well as recently published data26 do display evidence of co-contraction. Nevertheless, we recognise that these co-contraction patterns were not necessarily subject-specific but we do not believe this limitation influenced our conclusions. Further research utilising more subject-specific approaches, such as EMG-driven and EMG-hybrid modelling58,59, may yield further clinical insight.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that knee-spanning as well as non-knee-spanning muscles contribute substantially to anteroposterior shear forces as well as frontal and transverse plane joint reaction moments at the tibiofemoral joint. Specifically, the vasti and gastrocnemius muscles were found to be the major contributors to the anterior shear reaction force, whilst the biarticular hamstrings and the soleus were the major contributors to the posterior shear reaction force. The valgus knee joint reaction moment was primarily produced by both knee-spanning (vasti and biceps femoris long head) and non-knee-spanning (soleus) muscles. This moment was opposed by the non-knee-spanning gluteal muscles, particularly the gluteus medius, gluteus maximus and piriformis. The external rotation knee joint reaction moment throughout the weight acceptance phase of sidestep cutting was primarily generated by the vasti and soleus muscles. Based on our consideration of multiple loading states, we conclude that the hamstrings (biceps femoris long head and medial hamstrings), soleus, and the gluteals (especially gluteus medius) have the greatest potential to offset ACL loading during an unanticipated sidestep cutting task. Optimising the function of these muscles should therefore be of high priority in rehabilitative and preventative programs.

References

Ardern, C. L., Webster, K. E., Taylor, N. F. & Feller, J. A. Return to the preinjury level of competitive sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: two-thirds of patients have not returned by 12 months after surgery. The American journal of sports medicine 39, 538–543 (2011).

Janssen, K. W., Orchard, J. W., Driscoll, T. R. & van Mechelen, W. High incidence and costs for anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions performed in Australia from 2003–2004 to 2007–2008: time for an anterior cruciate ligament register by Scandinavian model? Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 22, 495–501, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01253.x (2012).

Øiestad, B. E., Engebretsen, L., Storheim, K. & Risberg, M. A. Knee Osteoarthritis After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Systematic Review. The American journal of sports medicine 37, 1434–1443, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546509338827 (2009).

Butler, D., Noyes, F. & Grood, E. Ligamentous restraints to anterior-posterior drawer in the human knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 62, 259–270 (1980).

Markolf, K. L. et al. Combined knee loading states that generate high anterior cruciate ligament forces. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 13, 930–935 (1995).

Markolf, K. L., Gorek, J. F., Kabo, J. M. & Shapiro, M. S. Direct measurement of resultant forces in the anterior cruciate ligament. An in vitro study performed with a new experimental technique. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 72, 557–567 (1990).

Kiapour, A. M. et al. Strain Response of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament to Uniplanar and Multiplanar Loads During Simulated Landings: Implications for Injury Mechanism. The American journal of sports medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546516640499 (2016).

Oh, Y. K., Lipps, D. B., Ashton-Miller, J. A. & Wojtys, E. M. What strains the anterior cruciate ligament during a pivot landing? The American journal of sports medicine 40, 574–583, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546511432544 (2012).

Krosshaug, T. et al. Mechanisms of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Basketball: Video Analysis of 39 Cases. The American journal of sports medicine 35, 359–367, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546506293899 (2007).

Waldén, M. et al. Three distinct mechanisms predominate in non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in male professional football players: a systematic video analysis of 39 cases. British Journal of Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094573 (2015).

Koga, H. et al. Mechanisms for Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Knee Joint Kinematics in 10 Injury Situations From Female Team Handball and Basketball. The American journal of sports medicine 38, 2218–2225, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546510373570 (2010).

Shin, C. S., Chaudhari, A. M. & Andriacchi, T. P. Valgus plus internal rotation moments increase anterior cruciate ligament strain more than either alone. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 43, 1484–1491, https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31820f8395 (2011).

Li, G. et al. The importance of quadriceps and hamstring muscle loading on knee kinematics and in-situ forces in the ACL. Journal of biomechanics 32, 395–400 (1999).

More, R. C. et al. Hamstrings—an anterior cruciate ligament protagonist An in vitro study. The American journal of sports medicine 21, 231–237 (1993).

Zajac, F. E. & Gordon, M. E. Determining muscle’s force and action in multi-articular movement. Exercise and sport sciences reviews 17, 187–230 (1989).

Delp, S. L. et al. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on 54, 1940–1950 (2007).

Hermens, H. J., Freriks, B., Disselhorst-Klug, C. & Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. Journal of electromyography and Kinesiology 10, 361–374 (2000).

Benoit, D. L. et al. Effect of skin movement artifact on knee kinematics during gait and cutting motions measured in vivo. Gait & posture 24, 152–164 (2006).

Cochrane, J. L., Lloyd, D. G., Buttfield, A., Seward, H. & McGivern, J. Characteristics of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in Australian football. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia 10, 96–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.015 (2007).

Olsen, O.-E., Myklebust, G., Engebretsen, L. & Bahr, R. Injury Mechanisms for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Team Handball: A Systematic Video Analysis. The American journal of sports medicine 32, 1002–1012, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546503261724 (2004).

Kristianslund, E., Krosshaug, T. & Van den Bogert, A. J. Effect of low pass filtering on joint moments from inverse dynamics: implications for injury prevention. Journal of biomechanics 45, 666–671 (2012).

Rajagopal, A. et al. Full-Body Musculoskeletal Model for Muscle-Driven Simulation of Human Gait. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 63, 2068–2079 (2016).

Walker, P. S., Rovick, J. S. & Robertson, D. D. The effects of knee brace hinge design and placement on joint mechanics. Journal of biomechanics 21, 965–974 (1988).

Lu, T.-W. & O’connor, J. Bone position estimation from skin marker co-ordinates using global optimisation with joint constraints. Journal of biomechanics 32, 129–134 (1999).

Millard, M., Uchida, T., Seth, A. & Delp, S. L. Flexing computational muscle: modeling and simulation of musculotendon dynamics. Journal of biomechanical engineering 135, 021005 (2013).

Mokhtarzadeh, H. et al. A comparison of optimisation methods and knee joint degrees of freedom on muscle force predictions during single-leg hop landings. Journal of biomechanics 47, 2863–2868, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.07.027 (2014).

Mokhtarzadeh, H. et al. Contributions of the Soleus and Gastrocnemius muscles to the anterior cruciate ligament loading during single-leg landing. Journal of biomechanics 46, 1913–1920, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.04.010 (2013).

Dorn, T. W., Schache, A. G. & Pandy, M. G. Muscular strategy shift in human running: dependence of running speed on hip and ankle muscle performance. The Journal of experimental biology 215, 1944–1956 (2012).

Lin, Y. C., Kim, H. J. & Pandy, M. G. A computationally efficient method for assessing muscle function during human locomotion. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Biomedical Engineering 27, 436–449 (2011).

Dorn, T. W., Lin, Y.-C. & Pandy, M. G. Estimates of muscle function in human gait depend on how foot-ground contact is modelled. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering 15, 657–668 (2012).

Morgan, K. D., Donnelly, C. J. & Reinbolt, J. A. Elevated gastrocnemius forces compensate for decreased hamstrings forces during the weight-acceptance phase of single-leg jump landing: implications for anterior cruciate ligament injury risk. Journal of biomechanics 47, 3295–3302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.08.016 (2014).

Besier, T. F., Lloyd, D. G., Cochrane, J. L. & Ackland, T. R. External loading of the knee joint during running and cutting maneuvers. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 33, 1168–1175 (2001).

Sritharan, P., Lin, Y. C. & Pandy, M. G. Muscles that do not cross the knee contribute to the knee adduction moment and tibiofemoral compartment loading during gait. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 30, 1586–1595 (2012).

Hicks, J. L., Uchida, T. K., Seth, A., Rajagopal, A. & Delp, S. L. Is My Model Good Enough? Best Practices for Verification and Validation of Musculoskeletal Models and Simulations of Movement. Journal of biomechanical engineering 137, 020905 (2015).

Neptune, R. R., Wright, I. C. & van den Bogert, A. J. Muscle coordination and function during cutting movements. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 31, 294–302 (1999).

Beaulieu, M. L., Lamontagne, M. & Xu, L. Lower limb muscle activity and kinematics of an unanticipated cutting manoeuvre: a gender comparison. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 17, 968–976, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-009-0821-1 (2009).

Oliveira, A., Silva, P., Lund, M. E., Kersting, U. G. & Farina, D. Fast changes in direction during human locomotion are executed by impulsive activation of motor modules. Neuroscience 228, 283–293 (2013).

Sigward, S. M. & Powers, C. M. The influence of gender on knee kinematics, kinetics and muscle activation patterns during side-step cutting. Clinical Biomechanics 21, 41–48 (2006).

Biscarini, A. et al. Voluntary enhanced cocontraction of hamstring muscles during open kinetic chain leg extension exercise: its potential unloading effect on the anterior cruciate ligament. The American journal of sports medicine 42, 2103–2112, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546514536137 (2014).

Neptune, R. R., Kautz, S. A. & Zajac, F. E. Contributions of the individual ankle plantar flexors to support, forward progression and swing initiation during walking. Journal of biomechanics 34, 1387–1398, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00105-1 (2001).

Neptune, R. R. & McGowan, C. P. Muscle contributions to whole-body sagittal plane angular momentum during walking. Journal of biomechanics 44, 6–12 (2011).

Adouni, M., Shirazi-Adl, A. & Marouane, H. Role of gastrocnemius activation in knee joint biomechanics: gastrocnemius acts as an ACL antagonist. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering 19, 376–385 (2016).

Fleming, B. C. et al. The gastrocnemius muscle is an antagonist of the anterior cruciate ligament. Journal of orthopaedic research 19, 1178–1184 (2001).

Solomonow, M. et al. The synergistic action of the anterior cruciate ligament and thigh muscles in maintaining joint stability. The American journal of sports medicine 15, 207–213 (1987).

Li, G., Rudy, T. W., Allen, C., Sakane, M. & Woo, S. L. Y. Effect of combined axial compressive and anterior tibial loads on in situ forces in the anterior cruciate ligament: a porcine study. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 16, 122–127 (1998).

Berns, G. S., Hull, M. & Patterson, H. A. Strain in the anteromedial bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament under combination loading. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 10, 167–176 (1992).

Fleming, B. C. et al. The effect of weightbearing and external loading on anterior cruciate ligament strain. Journal of biomechanics 34, 163–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(00)00154-8 (2001).

Sakane, M. et al. In situ forces in the anterior cruciate ligament and its bundles in response to anterior tibial loads. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 15, 285–293 (1997).

Gabriel, M. T., Wong, E. K., Woo, S. L. Y., Yagi, M. & Debski, R. E. Distribution of in situ forces in the anterior cruciate ligament in response to rotatory loads. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 22, 85–89 (2004).

Hewett, T. E. et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine 33, 492–501, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546504269591 (2005).

Khayambashi, K., Ghoddosi, N., Straub, R. K. & Powers, C. M. Hip muscle strength predicts noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury in male and female athletes: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine 44, 355–361 (2016).

Hashemi, J. et al. Hip extension, knee flexion paradox: a new mechanism for non-contact ACL injury. Journal of biomechanics 44, 577–585 (2011).

Lieberman, D. E. et al. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature 463, 531–535, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08723 (2010).

Smith, C. R., Vignos, M. F., Lenhart, R. L., Kaiser, J. & Thelen, D. G. The Influence of Component Alignment and Ligament Properties on Tibiofemoral Contact Forces in Total Knee Replacement. J Biomech Eng 138, 021017, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4032464 (2016).

Pandy, M. G. & Andriacchi, T. P. Muscle and joint function in human locomotion. Annual review of biomedical engineering 12, 401–433 (2010).

Lerner, Z. F., DeMers, M. S., Delp, S. L. & Browning, R. C. How tibiofemoral alignment and contact locations affect predictions of medial and lateral tibiofemoral contact forces. Journal of biomechanics 48, 644–650 (2015).

Wesseling, M. et al. Muscle optimization techniques impact the magnitude of calculated hip joint contact forces. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 33, 430–438 (2015).

Pizzolato, C. et al. CEINMS: A toolbox to investigate the influence of different neural control solutions on the prediction of muscle excitation and joint moments during dynamic motor tasks. Journal of biomechanics 48, 3929–3936 (2015).

Sartori, M., Farina, D. & Lloyd, D. G. Hybrid neuromusculoskeletal modeling to best track joint moments using a balance between muscle excitations derived from electromyograms and optimization. Journal of biomechanics 47, 3613–3621 (2014).

Acknowledgements

NM was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception of experimental procedures – N.M., A.G.S. and D.A.O. Conception of data analysis – N.M. and P.S. Data collection and analysis – N.M. Preparation of Figures – N.M. Interpretation of data – N.M., A.G.S., P.S. and D.A.O. Writing of manuscript – N.M., A.G.S., P.S. and D.A.O.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maniar, N., Schache, A.G., Sritharan, P. et al. Non-knee-spanning muscles contribute to tibiofemoral shear as well as valgus and rotational joint reaction moments during unanticipated sidestep cutting. Sci Rep 8, 2501 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-19098-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-19098-9

This article is cited by

-

An 8-week injury prevention exercise program combined with change-of-direction technique training limits movement patterns associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury risk

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Cross-sectional study on relationships between physical function and psychological readiness to return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation (2022)

-

Muscle function during single leg landing

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Divergent isokinetic muscle strength deficits in street running athletes

Sport Sciences for Health (2022)

-

Muscle Force Contributions to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Loading

Sports Medicine (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.