Abstract

Antibiotic resistance poses one of the greatest threats to global health today; conventional drug therapies are becoming increasingly inefficacious and limited. We identified 16 medicinal plant species used by traditional healers for the treatment of infectious and inflammatory diseases in the Greater Mpigi region of Uganda. Extracts were evaluated for their ability to inhibit growth of clinical isolates of multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens. Extracts were also screened for quorum quenching activity against S. aureus, including direct protein output assessment (δ-toxin), and cytotoxicity against human keratinocytes (HaCaT). Putative matches of compounds were elucidated via LC–FTMS for the best-performing extracts. These were extracts of Zanthoxylum chalybeum (Staphylococcus aureus: MIC: 16 μg/mL; Enterococcus faecium: MIC: 32 μg/mL) and Harungana madagascariensis (S. aureus: MIC: 32 μg/mL; E. faecium: MIC: 32 μg/mL) stem bark. Extracts of Solanum aculeastrum root bark and Sesamum calycinum subsp. angustifolium leaves exhibited strong quorum sensing inhibition activity against all S. aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) alleles in absence of growth inhibition (IC50 values: 1–64 μg/mL). The study provided scientific evidence for the potential therapeutic efficacy of these medicinal plants in the Greater Mpigi region used for infections and wounds, with 13 out of 16 species tested being validated with in vitro studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

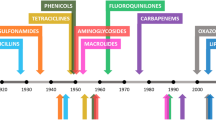

The rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) requires mobilization of political, financial and research investment due to its emergence as a global health hazard that threatens the ability to treat infectious diseases1. According to the World Health Organization, AMR poses “one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today” and can affect anyone in any country and of any age2. Today, AMR already accounts for 700,000 deaths annually. By 2050, this figure is estimated to reach more than 10 million deaths per year, which is more people than currently die from cancer3. Because effective antibiotics are critical for treatment of bacterial infections and for procedures where there is a high risk of infection, e.g. surgery, new anti-infectives are needed to overcome this global threat4. The issue of resistance is not uniformly spread across all bacteria5. Six species have been identified by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) as being especially dangerous due to their potential multidrug resistance mechanisms and virulence. They are referred to as ‘ESKAPE’ pathogens, which is an acronym for Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter species. This group of pathogenic bacteria encompasses both Gram-negative and Gram-positive species that are capable of ‘escaping’ bactericidal action of conventional antibiotics6,7. ESKAPE pathogens are common causes of deadly or life-threatening infections, especially among children, immunocompromised, and critically-ill people8.

Antibiotics are not the only anti-infectives that could provide an effective weapon against these pathogens. Another therapeutic, yet non-antibiotic, strategy is targeting bacterial virulence controlled by quorum sensing processes. The quorum-sensing mechanism mediated by signal molecules regulates the expression of virulence genes in the majority of pathogenic bacteria, meaning that quorum-sensing inhibitors are expected to be one of the best alternatives to antibiotics9,10. Autoinducers, self-secreted signal molecules, are regulated by a density-dependent synchronized gene expression system during quorum sensing11. Biofilm formation, toxin production and other virulence factors are controlled by quorum sensing and the production of virulence factors can weaken the balance of host defense mechanisms9. Initiation of toxin production occurs when extracellular signaling and communication indicates that a threshold population of bacteria has been achieved12. Inhibition of quorum sensing induced by secondary plant metabolites can significantly attenuate bacterial virulence and substantially enhance vulnerability to conventional antibiotics and to the immune system9,12,13,14.

It is estimated that more than 25% of the Western drugs prescribed contain plant-derived natural products as active ingredients15. Yet, only a small proportion of plant species has ever been investigated for pharmacological activity in a laboratory setting16,17. In East and Central Africa, medicinal plant use and traditional medicine practices are still the predominant form of healthcare18,19. In Uganda, four out of five patients primarily seek medical treatment from traditional healers instead of Western-trained physicians and there is at least one traditional healer per village practicing traditional use of medicinal plants20,21. Despite its small size, Uganda is characterized by its very rich biological diversity of 5,000 species of higher plants in the indigenous flora22, resulting from its unique bio-geographical location23. Documentation of traditional use and ethnopharmacological evaluation of this wealth of plant species can still be considered an understudied field.

A recent ethnobotanical study by Schultz et al. identified 16 medicinal plant species that play a significant role in the local traditional medicine of the Greater Mpigi region located in West-Central Uganda24. The local vegetation at the study site is characterized as a tropical, moist evergreen forest/savanna mosaic25,26. Here, people are highly dependent on medicinal plants and local traditional healers for primary health care. Apart from many other traditional uses documented, 16 medicinal plants were found to be critical to anti-infective traditional medicine practices in the Greater Mpigi region (in particular, skin and wound infections, and symptoms associated with bacterial infections). The majority of the plant species have not been studied for potential bioactivity yet24. As the ethnopharmacological basis for this study, these species, their traditional use in treatment of infections and the relative frequency of citation in % (n = 39) are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Ethnopharmacological information on the medicinal use of plant candidates from the Greater Mpigi region in Uganda (with emphasis on infections and symptoms of infections). The stacked histogram figure shows the relative frequencies of citation (RFC) in % in treatment of relevant medical disorders, calculated from data obtained through an ethnobotanical survey of 39 traditional healers. Here, the RFC assesses the importance of a plant species used for a specific medical condition relative to the total number of informants interviewed in the study. It varies from 0% (none of the informants uses this plant species in treatment of a specific medical condition) to 100% (maximum number of informants use this plant species in treatment of a specific medical condition)24. Consequently, the higher the value of cumulated RFCs (x-axis), the higher the traditional use of a plant species in treatment of medical conditions relevant to this study.

We screened 86 plant extracts derived from these 16 medicinal species for antibacterial activity against a panel of multidrug resistant ESKAPE pathogens associated with the medical disorders stated in Fig. 1, and for antivirulence activity in S. aureus (Fig. 2). The extracts were produced from plant material collected in the Greater Mpigi region during fieldwork in 2015, 2016 and 2017. The overarching aims of the study were to contribute to drug discovery and pharmacological evaluation of traditional use. Specifically, the study objectives were to investigate the potential (1) growth inhibitory impact of the medicinal plants on a panel of ESKAPE pathogens; (2) quorum-quenching activity targeting the agr system of S. aureus; (3) mammalian cytotoxicity against the HaCaT keratinocyte cell line from adult human skin; (4) inhibition of δ-toxin production in S. aureus; and (5) to conduct a chemical characterization for putative natural product matches of the four most bioactive extracts.

Research methodology for the study—16 plant species were identified in close collaboration with the traditional healers of the Greater Mpigi region based on the species’ traditional use in treatment of infections. After collecting specimens and producing a medicinal plant extract library, our in vitro study commenced, targeting bacterial virulence and growth of multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens. After initial growth inhibition, quorum quenching and cytotoxicity library screenings, hits were followed up via dose–response studies, a δ-toxin production inhibition assay and chemical characterization. Results of this study will ultimately be transferred back to the traditional healers through field workshops.

Results

Extraction and information on plant species

Extractions were achieved by means of (a) maceration in either methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate or diethyl ether; (b) Soxhlet extraction using n-hexane and successively methanol; and (c) aqueous decoction. These procedures yielded a total of 86 different plant crude extracts from 16 medicinal plant species. Details on the medicinal plants investigated, herbarium voucher specimen numbers, local plant names in Luganda, plant parts investigated, extract identification numbers (extract IDs) and solvents used for extraction are reported in Supplementary Table S1.

Growth inhibition library screen and dose–response study against multi-resistant ESKAPE panel

Extracts were initially screened for growth inhibition of one clinical isolate of each ESKAPE pathogen at a concentration of 256 μg/mL. Extracts displaying an inhibition percentage above 40 for an individual strain were further investigated by dose–response experiments in order to obtain the IC50 and MIC (IC90) values. In this initial library screen, none of the extracts from Ficus saussureana, Microgramma lycopodioides, Plectranthus hadiensis and Securidaca longipedunculata displayed significant activity at this initial screening concentration and were therefore eliminated from further experiments. However, 26 of the 86 extracts were investigated further. In the second experimental stage, a total of 10 extracts from seven plant species inhibited the growth of E. faecium (EU-44). While growth of S. aureus (UAMS-1) was significantly inhibited by 14 extracts from nine plant species at 256 μg/mL, only six extracts from three species were active against K. pneumoniae (CDC-004). Fifteen extracts from nine plant species were introduced to dose–response studies against A. baumannii (CDC-0033), and eight extracts from six plant species against P. aeruginosa (AH-71) respectively. Only the ethanolic and diethyl ether extracts from Harungana madagascariensis stem bark (etE011-18, dietE011) showed growth inhibition above 40% against E. cloacae (CDC-0032) at the initial screening concentration of 256 μg/mL. The individual plant extracts selected for the dose-response study and their results are shown in Table 1.

The diethyl ether extract of Zanthoxylum chalybeum stem bark (dietE017a) displayed the highest inhibitory activities in the study: S. aureus (IC50: 4 μg/mL; MIC: 16 μg/mL) and E. faecium (IC50: 8 μg/mL; MIC: 32 μg/mL). Ethanolic (etE011-18), diethyl ether (dietE011) and hexane extracts (hE011-18) of H. madagascariensis stem bark were the second most active extracts against growth of S. aureus (IC50: 8 μg/mL; MIC: 32 μg/mL) and the ethanolic stem bark extract displayed considerable antibiotic properties against E. faecium, resulting in the same IC50 (8 μg/mL) and MIC (32 μg/mL) values as Z. chalybeum. None of the extracts yielded an MIC at the concentration range tested (≤ 256 μg/mL) in the experiments with K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and E. cloacae. Furthermore, 50% growth inhibition of E. cloacae was not achieved by the two H. madagascariensis stem bark extracts (etE011-18, dietE011) that were tested, meaning that none of the 86 extracts were active against the multidrug-resistant CDC-0032 strain. The ethanolic extract of Combretum molle stem bark (etE015) exhibited modest activity against A. baumannii (IC50: 32 μg/mL; MIC: > 256 μg/mL). Growth of P. aeruginosa was moderately inhibited by the ethanolic extract of C. molle stem bark (etE015; IC50: 16 μg/mL; MIC: 128 μg/mL) and Morella kandtiana roots (etE012-18a; IC50: 32 μg/mL; MIC: 256 μg/mL).

Quorum sensing inhibition in Staphylococcus aureus

In S. aureus, a number of quorum-sensing component pathways are encoded by the accessory gene regulator (agr) system, which plays a key role in the species’ pathogenesis14. There are four allelic groups on the agr gene locus: agr I–IV27. The importance of the agr system to abscess formation has previously been confirmed by means of genetic and agr-inhibiting tools28,29,30,31,32.

During an initial screening, all 86 extracts were tested for inhibition of quorum sensing against the strain S. aureus agr I reporter strain AH-1677 at 16 μg/mL (sub-IC50 concentrations for growth were used to avoid potential growth inhibition effects). A total of 11 extracts from seven plant species revealed quorum-sensing inhibition activity above 40% and were selected for dose-response experiments with four reporter strains of S. aureus agr subtypes (agr I: AH-1677, agr II: AH-430, agr III: AH-1747, agr IV: AH-1872). These plant species, which were significantly active in the initial screen, were Sesamum calycinum subsp. angustifolium (both hexane leave extracts; hE004 and hE004-18), Leucas calostachys (hexane leave extract; hE005), Solanum aculeastrum (hexane root extract; hE006, and ethyl acetate root extract; eE006), Z. chalybeum (ethyl acetate stem bark extract; eE009), M. kandtiana (both diethyl ether root extracts; dietE012 and dietE012-18), Warburgia ugandensis (diethyl ether stem bark extract; dietE014) and P. hadiensis (hexane leave extract; hE016, and diethyl ether leave extract; dietE016) (Table 2). None of the extracts from S. longipedunculata, M. lycopodioides, F. saussureana, Albizia coriaria, Erythrina abyssinica, T. asiatica, H. madagascariensis and C. molle inhibited quorum sensing above 40% at 16 μg/mL.

Ugandan medicinal plant species exhibit dose-dependent quorum-sensing inhibition in vitro

The transcription of each of the four known agr allelic groups was inhibited by all of the selected 11 crude extracts from seven plant species. Strains were additionally monitored for potential growth inhibition by optical density (600 nm). Dose-response curves, indicating the percent growth inhibition and quorum sensing inhibition (QSI) activity of the vehicle control (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]), were calculated to evaluate the antivirulence activity (Fig. 3). Agr subtype-specific IC50 values are reported in Table 3. The two hexane extracts of S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium leaves, hE004 and hE004-18, were identified as the most active quorum-sensing inhibitors. The IC50 against agr I–IV were 2, 2, 16 and 32 μg/mL (hE004), 4, 2, 16 and 32 μg/mL (hE004-18) respectively. Another plant extract highly active in tackling bacterial virulence was the ethyl acetate extract of S. aculeastrum roots (eE006), which scored agr subtype-dependent IC50 values of 4, 1, 16 and 64 μg/mL. Two more promising quorum-sensing inhibitors were the hexane extract of S. aculeastrum roots (hE006, agr I–III IC50: 12, 2 and 16 μg/mL), which only displayed moderate activity against agr IV (IC50: 64 μg/mL), and the hexane extract of L. calostachys leaves (hE005, agr I–II: 4 μg/mL), which was moderately active against agr III and IV (IC50: 64 μg/mL). Extracts of W. ugandensis and Z. chalybeum stem bark showed low IC50 values ranging from 8–32 μg/mL, but were eliminated from the anti-agr assessment due to their strong growth inhibitory activity on our reporter strains. No MIC values were detected (either > 64 μg/mL or growth inhibition), except for the hexane extract of S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium leaves (hE004-18, MIC: 64 μg/mL).

Results of the quorum-sensing inhibition in vitro dose-response studies: Data shown as serial dilution and percent agr activity or growth of the vehicle control (DMSO) at 22 h; FLD: fluorescence detector (measuring quorum sensing activity), represented by solid lines; OD: optical density at 600 nm (measuring bacterial growth), represented by dashed lines.

δ-Toxin production and quantification assay

The phenol-soluble modulin peptide δ-toxin (also known as δ-hemolysin) is responsible for various pathophysiological effects caused by S. aureus as it seeks to evade host defense mechanisms33,34,35,36. These effects include cytolysis of red and white blood cells, followed by cell death, as well as triggering of inflammatory responses33,36. Extracts hE004, hE004-18, hE005, eE006, hE006, which displayed strong quorum sensing inhibitory activity (Table 3), were selected for further confirmation of antivirulence effects on the translational products of agr in S. aureus. These in vitro experiments aimed to measure δ-toxin levels during extract treatment at sub-growth inhibitory concentrations through examination of the bacterial supernatant using hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC)37. The experiments were conducted with two high-toxin-producing strains of S. aureus: AH1263 and NRS243. All tested extracts were effective in significantly reducing δ-toxin in AH1263, confirming their antivirulence activity. The hexane extracts of S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium leaves (hE004, hE004-18) and the ethyl acetate extract of S. aculeastrum roots (eE006) displayed the highest inhibition activity against NRS243. Extracts hE005 and hE006 showed moderate activity against NRS243 (Fig. 4).

Five extracts from three Ugandan medicinal plant species exhibited strong δ-toxin production inhibition activity against S. aureus AH1262 (A) and moderate activity against S. aureus NRS243 (B); extracts were tested at 32, 16 and 8 μg/mL (sub-growth inhibition concentrations) and compared to the untreated control (UT). The positive control 224CF2c was additionally tested at 64 μg/mL. All samples were normalized for growth (OD600nm) during supernatant harvest. Results are reported as the total peak area and peaks are identified as deformylated (blue) and formylated (red) δ-toxin peak areas. Statistical significance is denoted as *P value < 0.05, ‡P value < 0.01, †P value < 0.001.

Medicinal plants from the Greater Mpigi region exhibit low toxicity to human keratinocytes

In an effort to assess the cytotoxicity of the plant extracts, all 86 extracts were screened in a human keratinocyte toxicity assay at 64 μg/mL, using HaCaT cells. In this library screen, only one of the 86 extracts from 16 plant species exhibited a cytotoxicity above 50%. The only extract displaying cytotoxic activity in the initial screen was the methanolic extract of S. aculeastrum roots smE006 (I%: 51.8 ± 1.5). Results of the cytotoxicity library screen are shown in Supplementary Table S3. Subsequently, dose-response experiments to assess cytotoxicity were conducted on extract smE006, the 26 active hits from the growth inhibition library screen (see Table 1) and the five most active quorum-sensing inhibitors that were introduced to the δ-toxin production inhibition assay (see Figs. 3 and 4, Table 3). Results of this counterscreen are shown in Table 4, along with the calculated therapeutic indices for growth inhibition (TIgrowth inhibition) for individual strains tested and quorum-sensing inhibition (TIquorum quenching) for each reporter gene targeted. The therapeutic index is used as an important parameter in drug discovery to assess an appropriately balanced safety-efficacy profile for a given indication, as it enables for characterization and optimization of efficacy and safety of drug candidates38. The majority of extracts tested in our dose-response study displayed no toxicity to the HaCaT cells (20 extracts, 64.5%). However, some extracts did show low toxicity with IC50 values ranging from 512 to 256 μg/mL: (1) the ethyl acetate extract of S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium leaves (eE004-18); (2) three extracts of L. calostachys leaves (eE005-18, hE005, hE005-18); (3) two extracts of S. aculeastrum roots (hE006, smE006); (4) the diethyl ether extract of Toddalia asiatica leaves/stem bark (dietE010); and (5) four extracts of H. madagascariensis stem bark (etE011-18, dietE011, dietE011-18, hE011-18). As expected, extract smE006 remained the most cytotoxic sample in the extract library, displaying an IC50 of 64 μg/mL.

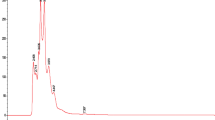

LC–MS analysis of plant extracts for putative matches

The two best performing extracts of the growth inhibition experiments (dietE017a and etE011-18), as well as of the quorum-sensing and δ-toxin production assays (hE004-18 and eE006) were further investigated by chemical characterization via liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis and searched for putative matches. The base peak negative mode electrospray ionization (ESI) LC–MS chromatograms for the four extracts are shown in Fig. 5. A total of 60 peaks were identified and screened for putative matches (Fig. 5 and Table 5). This resulted in 10 peaks having putative matches for etE011-018, 9 peaks for hE004-18, 9 peaks for eE006, and 2 peaks for dietE017a. Most of the ions yielded several putative matches which are isomers of the experimentally determined empirical formula. The only putative match for dietE017a, peak 54 and 55, was cyclozanthoxylane A, which has a mass difference of over 13 ppm from the experimentally determined mass. While this is a low probability match, it was the only putative match for the Z. chalybeum sample from 9,463 published compounds in the genus. Chemical structures for the putative matches from the four extracts are provided in Supplementary Figures S3, S4, S5 and S6.

Discussion

The study provides scientific evidence for the therapeutic use of medicinal plants in the Ugandan Greater Mpigi region. Traditional use in treatment of infections and wounds was successfully validated in 13 out of 16 medicinal plant species investigated using in vitro studies. Extracts of species displaying no pharmacological activity in these experiments were S. longipedunculata, M. lycopodioides and F. saussureana. On the contrary, different extracts of S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium, L. calostachys, S. aculeastrum, M. kandtiana, W. ugandensis and Z. chalybeum simultaneously displayed both growth inhibition and quorum-sensing inhibition effects on the strains investigated. Extracts from the same species distinguished themselves in terms of polarity of extraction solvent used (“pre-fractionation”). Except for the hexane extract of S. aculeastrum roots hE006, there was no extract that was simultaneously active in inhibiting bacterial growth and quorum quenching, which highlights the need for bioassay-guided fractionation and isolation of active compounds from these species in the future.

In general, extracts produced as aqueous decoction, which is consistent with the majority of the traditional preparations in the Greater Mpigi region24, failed to display bioactive effects in our in vitro models. The exception was one aqueous extract of M. kandtiana roots, which exhibited low inhibitory effects on the growth of A. baumannii CDC-0033 (IC50: 128 μg/mL; MIC: > 256 μg/mL) and moderate effects on P. aeruginosa AH-71 (IC50: 32 μg/mL; MIC: 256 μg/mL). One possible factor that could contribute to this phenomenon is the fact that extracts are standardized in the lab (filtered before solvent evaporation), unlike during traditional treatment where solids are swallowed along with the infused water. In this way, apolar pharmacologically active secondary plant metabolites bound to the solids remain in the decoction and could potentially yield a pharmacological effect in the patient.

Extract dietE017a, a diethyl ether extract of Z. chalybeum stem bark, displayed the highest growth inhibitory activity of all extracts against growth of S. aureus (IC50: 4 μg/mL; MIC: 16 μg/mL) and E. faecium (IC50: 8 μg/mL; MIC: 32 μg/mL). Although representing a mixture of hundreds of secondary plant metabolites, dietE017a surprisingly reached a similar level of antibiotic activity exhibited in vitro by the single compound positive controls, namely chloramphenicol (S. aureus, IC50: 4 μg/mL; MIC: 32 μg/mL) and vancomycin (E. faecium, IC50: 4 μg/mL; MIC: 4 μg/mL). Extract dietE017a exhibited no cytotoxic effects in the human keratinocyte cell line (Cytotoxicity IC50: > 515 μg/mL). The calculated therapeutic index (TI) demonstrated that cytotoxicity to human cells was at concentrations > 128 (S. aureus) and > 64 (E. faecium) times higher than that required for growth inhibition of these pathogenic bacteria. In the Greater Mpigi region, none of the informants stated that Z. chalybeum is used as an herbal drug for skin infections. Instead, 18% of the traditional healers interviewed stated that this deciduous shrub or tree is used for wound disinfection and treatment. It was also reported that it is used medicinally for treatment of stomach/GI tract disorders (13%), nausea (8%) and sore throat (8%)24. These results support the traditional use of Z. chalybeum stem bark as an anti-infective therapy. Z. chalybeum has been moderately studied in the past. The majority of publications documented its traditional use in Uganda24,39,40,41,42, Kenya43, Tanzania44 and Ethiopia45. Fagaramide, an antiplasmodial natural product, was previously isolated from Z. chalybeum stem bark46. In contrast to our results, diverse extracts of stem bark did not show any antibacterial activity against S. aureus up to a concentration of 100 mg/mL in two other studies published in 2001 and 201147,48. The present work offers the first report of antibiotic properties of Z. chalybeum stem bark against growth of multiresistant S. aureus and E. faecium.

Another highly active extract in terms of growth inhibition was an ethanolic extract of H. madagascariensis stem bark (etE011-18), displaying the same IC50 (8 μg/mL) and MIC (32 μg/mL) values against E. faecium EU-44 as Z. chalybeum (dietE017a). Extract etE011-18 also highly inhibited growth of S. aureus UAMS-1 (IC50: 8 μg/mL; MIC: 32 μg/mL). Although there was low cytotoxicity against human keratinocytes recorded (IC50: 256 μg/mL), the TI still reached an excellent value of 32 for both strains. H. madagascariensis has been extensively studied in the past and reports on traditional medicine describe medicinal use all over the African continent49,50,51,52,53,54. One study sought to evaluate the antibacterial activity of stem bark from H. madagascariensis against bacterial species also tested in our study55. In this study, a hydro-ethanolic extract displayed low inhibitory effects on two P. aeruginosa strains (MIC: 500 μg/mL) and moderate effects on two S. aureus strains (MIC: 62.5 μg/mL and 125 μg/mL). Although much work has been done on this evergreen shrub or tree, including isolation of compounds56,57,58,59, our study is the first to report on the strong growth inhibitory activity of the stem bark of this species, targeting multiresistant ESKAPE pathogens, especially E. faecium and S. aureus. This finding strongly supports the traditional medicinal use of H. madagascariensis in the Greater Mpigi region, where it was highly cited to be efficient in treatment of skin infections (relative frequency of citation: 31%, n = 39); wound treatment (31%); stomach/gastrointestinal (GI) tract disorders (21%); nausea (13%), sore throat (13%); and fever (18%)24.

As stated above, the stem barks of Z. chalybeum and H. madagascariensis are particularly often used in plant-based antibiotic treatment of stomach/GI tract disorders and wounds in the Greater Mpigi region. Our study identified certain extracts of these stem barks as being highly effective in inhibiting bacterial growth of multidrug-resistant strains of E. faecium and S. aureus. Enterococci are mostly commensal non-pathogenic bacteria, present in the GI tract without causing human infections60. However, in past decades, E. faecium strains have emerged as one of the most pervasive nosocomial pathogens worldwide that caused numerous outbreaks of serious infections61,62. E. faecium managed to circumvent conventional antibiotics, such as vancomycin, and successfully adapted to hospital environments, making it difficult to target pharmacologically63,64. With regards to its prevalence in Africa, regional pathogenic strains of E. faecium were identified to possess the lowest vancomycin resistance rates worldwide, but at the same time the highest resistance to ampicillin (data provide by WHO regional offices)65. This might be due to regional scarcity and high prices for wide-spectrum antibiotics and higher prescription of narrow-spectrum antibiotics66. The traditional use of Z. chalybeum and H. madagascariensis is still widely practiced for treatment of stomach/GI disorders in our study region and specific use against E. faecium was therefore validated in this study. S. aureus is a ubiquitous colonizer of the human epithelia, e.g. the skin, the upper respiratory tract and the GI tract67. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) can cause serious, sometimes fatal, infections upon invading the blood-stream or internal tissues, whereas wounds are often the source of infection68,69. According to the results of our study, the traditional use of Z. chalybeum and H. madagascariensis stem barks in wound treatment and disinfection therefore seems justified in order to prevent and combat a S. aureus infection, among others.

None of the extracts reached an MIC in the growth inhibition experiments with K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and E. cloacae (maximum concentration tested at 256 µg/mL) and the lowest IC50 values reported were 256 μg/mL for K. pneumoniae (dietE010, T. asiatica) and 32 μg/mL for A. baumannii (etE015, C. molle). Moreover, none of the 86 extracts were showed antibacterial effects on the growth of the multiresistant E. cloacae CDC-0032 strain.

Another set of extracts displayed antivirulence activity and was highly effective in the quorum sensing inhibition and the δ-toxin production screen. Selectively inhibiting quorum sensing pathways could prove to be an efficient alternative to antibiotics that simply try to kill the pathogen. One advantage of targeting the agr system is disruption of a wide variety of virulence factors, instead of targeting each virulence factor individually70,71. Use of botanical formulations or small molecule quorum sensing inhibitors isolated from medicinal plants might offer some additional benefits, e.g. protection of commensal bacteria that induce protective responses to prevent invasion and colonization by pathogens as part of the human host defense70,72,73. Many virulence factors are not of relevance to the overall survival of the pathogen. QSI therefore provides a less selective pressure towards resistance, facilitating a promising alternative therapy when combatting pathogens that are likely to develop resistance mechanisms during strong selective pressure of conventional treatment with antibiotics73,74,75.

The ethyl acetate root extract of S. aculeastrum (eE006) was among the two most QSI-active extracts, showing reporter gene subtype-dependent IC50 values of 4, 1, 16 and 64 μg/mL (agr I-IV). Its antivirulence activity was successfully confirmed in the δ-toxin production screen, where it significantly attenuated δ-toxin biosynthesis in our high-toxin-producing model strains. Extract eE006 exhibited no cytotoxicity in our model at the highest tested concentration of 512 μg/mL and calculated TIs were as high as > 128 (agr I)., > 512 (agr II)., > 32 (agr III). and > 8 (agr IV). S. aculeastrum is regarded an understudied species and our study accomplished to identify the roots of S. aculeastrum as strong quorum sensing inhibitor for the first time. Previous publications encompass use in African folklore medicine24,76,77,78,79. Pharmacological studies published on this species investigated the fruits or leaves, but not the roots80,81,82,83,84. For instance, fruits and leaves were investigated for antimicrobial activity against food-borne pathogens, but MIC values were only in the mg/mL range85. Steroidal alkaloids have previously been isolated from the root bark and fruits, such as solaculine A86 which induced induces non-selective cytotoxicity and P-glycoprotein inhibition87. At our field study location, the Greater Mpigi region, this poisonous nightshade species, whose berries contain α-solanine88, is often used in disinfection and treatment of wounds (23%) and fever (15%)24. The pharmacological effects of the roots, claimed by the traditional healers, might be explained by its now reported antivirulence activity, but should be further investigated through additional studies.

The hexane extract of S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium leaves (hE004-18) also exhibited strong antivirulence effects. Quorum sensing inhibition IC50 values against agr I–IV were as low as 4, 2, 16 and 32 μg/mL. No cytotoxicity was found, suggesting that use of this plant extract and species is safe to human cells. Calculated TIs are reported as > 128 (agr I), > 256 (agr II), > 32 (agr III) and > 16 (agr IV). S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium is still a highly understudied species with only five studies previously being published on its traditional medicinal use24,89,90,91,92 and one study that reported the presence of the hydrocarbon nonacosane and the glucosinolate, glucoiberverin93 in its leaves. Traditional healers in the Greater Mpigi region claimed that the leaves of this medicinal herb are often used to treat skin infections (15%), wounds (26%), disorders of the stomach/GI tract (13%), sore throats (10%) and fever (10%)24. Our study provides the first report of antivirulence activity, targeting quorum sensing and δ-toxin production in S. aureus, validating S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium application as anti-infective herbal drug.

Furthermore, our quorum sensing inhibition experiments showed that eE006 and hE004-18 displayed lower IC50 and MIC values than the positive control (224CF2c). This is particularly interesting because 224CF2c is not a crude extract, but a refined fraction of the European chestnut (Castanea sativa) that was previously identified to be highly active against agr I–IV14. Future bioassay-guided fractionation of the crude extracts eE006 and hE004-18 from the Ugandan rainforests could result in promising novel natural products aiming towards discovery of antivirulence drugs. The traditional use of S. aculeastrum roots (eE006) and S. calycinum subsp. angustifolium leaves (hE004-18) in wound treatment24 indicates that these extracts might demonstrate a significant reduction in dermonecrosis after infection with a virulent strain of MRSA, as shown with QSI-active fractions from Schinus terebinthifolia (Brazilian Peppertree) and Castanea sativa (European Chestnut) before13,14. Moreover, it will be essential to further investigate the ability of eE006 and hE004-18 in limiting the severity of disease and in increasing efficacy of conventional antibiotics. This includes potential activation of other virulence pathways, such as biofilm formation and secretion systems. Further experiments are also needed in order to assess the actual decrease of S. aureus virulence in vivo.

Methods

Ethnobotanical data

Information on traditional use for medical treatment among 39 traditional healers in the Greater Mpigi region in Uganda was obtained by means of an ethnobotanical survey. Results of this study were previously published24 and serve as a basis for the antibacterial and antivirulence experiments.

Collection and identification of plant material

Plant specimens were collected under guidance of the traditional healers during fieldwork in 2015, 2016 and 2017, while following standard collection procedures94. The approach for plant identification and assignment of scientific names was adapted from Weckerle et al. 95. Scientific names were cross-checked with https://www.theplantlist.org. Plant family assignments follow The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV guidance96. Voucher specimens of all species collected were deposited at Makerere University Herbarium in Kampala, Uganda and select specimens were also deposited at the Emory University Herbarium (GEO) in Atlanta, GA, USA and made digitally available on the SERNEC portal97 (Supplementary Table S1).

Extraction

Plant samples were shade dried and ground prior to extraction (Supplementary Figure S1). Extractions were performed as described in the flow sheet (Supplementary Figure S2). Briefly, plant material was either extracted by maceration, Soxhlet extraction or aqueous decoction. In order to selectively extract different compounds from the samples, extraction procedures were conducted using solvents of different polarities. Some plant species were collected for a second time in order to facilitate for production of higher amounts of extract. These upscaled extractions were performed in 2018 and resulting extracts received the additional information “-18” in their extract ID.

Bacterial strains

Multidrug-resistant clinical isolates were used in all growth-inhibition experiments in order to realistically assess the results of this study for future drug discovery advances for AMR threats. This study used 12 strains from six bacterial species recognized as ESKAPE pathogens, including Gram-negative [Klebsiella pneumoniae (CDC-004), Acinetobacter baumannii (CDC-0033), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (AH-71) and Enterobacter cloacae (CDC-0032)] and Gram-positive [Enterococcus faecium (EU-44) and Staphylococcus aureus (UAMS-1, AH-1677, AH-430, AH-1747, AH-1872, AH-1872, NRS243)] species. Strain characteristics, antibiotic resistance profiles and sources are reported in Supplementary Table S2. After streaking from freezer stock and overnight incubation at 37 °C, all strains were maintained on tryptic soy agar (TSA). Overnight liquid cultures were achieved in tryptic soy broth (TSB) at 37 °C and with constant shaking at 230 rpm. Appropriate positive controls (antibiotics or quorum quenchers) and negative controls (vehicle control, sterile media control) were always incorporated into the assays. All bacterial experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated at least once on a separate day.

Growth inhibition assay

All growth inhibition experiments were conducted following the guidelines set by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution testing98. Standardized working cultures were calculated and diluted from TSB overnight cultures in cation-adjusted Müller-Hinton broth (CAMHB). This was achieved using a BioTek Cytation3 and based on the cultures’ optical density (OD590 nm) to a confluence of 5 × 105 CFU/mL. The working culture was pipetted into 96-well microtiter plates (Greiner Bio-One International, CELLSTAR 655–185) and extracts and controls were added. Vehicle controls, sterility controls and antibiotic controls (1–64 µg/mL) were included on the plate setup. After initial optical density readings at 600 nm to account for extract absorbance, plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h (E. faecium, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. cloacae) or for 22 h (A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae). A final optical density measurement was performed, and the percent inhibition was calculated as previously described99. Growth inhibition is reported as the IC50 (the lowest concentration at which a sample displayed ≥ 50% inhibition) and MIC (the lowest concentration at which a sample displayed ≥ 90% inhibition).

All extracts were tested at a concentration of 256 µg/mL during an initial screen. Extracts that displayed a percent inhibition above 40% for an individual strain were further examined by dose-response experiments to obtain the IC50 and MIC values. Using two-fold serial dilution, extracts and vehicle were tested at concentrations ranging from 2 to 256 µg/mL.

agr reporter assay

An initial library screen was first conducted against the agr I reporter strain of S. aureus at 16 μg/mL (sub-MIC concentrations). After identification of extracts that displayed > 40% inhibition, candidates were further examined by dose-response studies (0.5–64 μg/mL) against all four accessory gene regulator (agr) subtypes of S. aureus. Crude extracts were tested as previously described14,100. Briefly, the agr reporter strains were grown and maintained in TSB and TSA, supplemented with chloramphenicol (10 μg/mL). All agr inhibition assays were conducted in 96-well, tissue culture-treated, black-sided microtiter plates (Costar 3,603, final well volume: 200 μL). Microtiter plates were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37 °C, while shaking at 1,200 rpm (Stuart SI505). At initial (0 h) and final (22 h) time points, OD600nm and fluorescence (493 nm excitation, 535 nm emission) were measured using a plate reader (BioTek Cytation3). Controls included a vehicle control (DMSO) and a positive control (224CF2c). 224CF2c is an QSI-active fraction extracted from the European chestnut (Castanea sativa), as reported in a previous study by the authors14. The quorum-quenching activity was reported as percent vehicle of the signal of the individual reporter train’s yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). Dose–response curves were generated using the GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). IC50 and MIC values were calculated as in the growth inhibition experiments described above.

Production of δ-toxin and quantification by HIC-HPLC

To confirm antivirulence activity on the translational products of agr in S. aureus (decline in δ-toxin biosynthesis), the most active extracts of the agr reporter assay were tested at 8, 16, and 32 μg/mL and compared to an untreated control in a δ-toxin production assay using high-toxin-producing strains of S. aureus (AH1262 and NRS243) by hydrophobic interaction chromatography as previously described37. The positive control 224C-F2c was additionally tested at 64 μg/mL. Data integration was normalized for growth (OD600nm) during supernatant harvest and reported as formylated and deformylated δ-toxin, visualized by a stacked histogram chart. The data was analyzed using a Student's t-test and statistical significance was denoted as *P value < 0.05, ‡P value < 0.01, †P value < 0.001.

Human keratinocyte toxicity assay

Potential cytotoxicity of extracts was assessed using immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaTs cells) combined with a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) test kit (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO, USA) as previously described by Quave et al.14. All extracts were initially tested at a concentration of 64 μg/mL. In effort to calculate the therapeutic index (TI), samples selected for dose-response cytotoxicity testing were extracts that (a) displayed cytotoxic activity above 50% inhibition in the library screen at 64 μg/mL, (b) were introduced as library-screen-active candidates to the growth inhibition dose-response studies and (c) were identified as being most active in the quorum sensing-dose-response studies and were investigated further in the δ-toxin production and quantification assay. Dose-response cytotoxicity experiments were conducted at a concentration range of 2–256 μg/mL. Percent of the vehicle (DMSO, v/v) in the well was < 2% for all experiments. All human keratinocyte toxicity experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated at least once on a separate day. The TI for growth inhibition and the TI for quorum-sensing inhibition (agr I-IV) were calculated by dividing the IC50 for extract cytotoxicity by the IC50 for its respective antibacterial activity.

LC–MS characterization of extracts

Extracts displaying the highest anti-growth and antivirulence activity in the in vitro assays, as well as the highest TI, were selected for chemical characterization. These extracts were examined by negative ESI mode Liquid chromatography-Fourier transform mass spectrometry (LC-FTMS) using a Thermo Scientific LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer equipped with a Shimadzu SIL-ACHT auto sampler and Dionex 3600SD HPLC pump. A 20 μL injection of the extract at 10 mg/mL dissolved in ethyl acetate, 1:1 ethyl acetate:methanol, or DMSO was made onto a Phenomenex Kinetex C18 150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm with compatible guard column at room temperature. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid in water and (B) 0.1% formic acid in Optima LC/MS acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The gradient program began with initial conditions of 98:2 A:B, which were held for 3 min, then changed to 100% B over 15 min using a linear gradient, 100% B was held for 25 min, before returning to initial conditions to equilibrate the column. The capillary temperature and voltage were 275.0 °C and − 48.00, the sheath gas flow 40, source voltage and current − 5.0 kV and 100.0 μA. All MS data was collected in negative MS1 mode scanning from m/z 150–1,500 with data dependent MS2 collected on the top 4 most abundant ions. The data was collected and processed using Thermo Scientific Xcalibur 2.2 SP1.48 software.

Putative compounds for each extract were determined by searching The Dictionary of Natural Products (CRC Press) and Scifinder (Chemical Abstracts Service) for compounds consistent with each MS1 peak’s parent ion m/z (± 1 Da). For The Dictionary of Natural Products ions were searched against all compound records for the extract’s genus. During searches in Scifinder, ions were screened against compounds published from the same genus as the extract in books, clinical trials, commentaries, conference proceedings, dissertations, editorials, journals, letters, reports, and review articles; entries from patents and preprints were not included in the search. Any matches from these databases were compared to the empirical formulas derived from the experimental MS data. Compounds which matched the empirical formula with a calculated mass error < 10 ppm were investigated further in the literature and reported. When no matches in the literature were found, the hydrocarbon with the lowest mass error was reported. Due to search limitations in Scifinder, only compounds published prior to 2005 were searched for the genus Solanum. All searches were performed in Feb. 2020.

References

Chandler, C. I. R. Current accounts of antimicrobial resistance: stabilisation, individualisation and antibiotics as infrastructure. Palgrave Commun. 5, 53. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0263-4 (2019).

WHO. World health organization fact sheet: antibiotic resistance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (2018).

O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations (Wellcome Trust and the UK Department of Health, London, 2016).

Thabit, A. K., Crandon, J. L. & Nicolau, D. P. Antimicrobial resistance: impact on clinical and economic outcomes and the need for new antimicrobials. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 16, 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2015.993381 (2015).

Rice, L. B. Progress and challenges in implementing the research on ESKAPE pathogens. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 31(Suppl 1), S7-10. https://doi.org/10.1086/655995 (2010).

Boucher, H. W. et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1086/595011 (2009).

Mulani, M. S., Kamble, E. E., Kumkar, S. N., Tawre, M. S. & Pardesi, K. R. Emerging strategies to combat ESKAPE pathogens in the era of antimicrobial resistance: a review. Front. Microbiol. 10, 539–539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00539 (2019).

Santajit, S. & Indrawattana, N. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2475067. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2475067 (2016).

Santhakumari, S. & Ravi, A. V. Targeting quorum sensing mechanism: an alternative anti-virulent strategy for the treatment of bacterial infections. S. Afr. J. Bot. 120, 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2018.09.028 (2019).

US Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Disease Control. AR report 2019: antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf (2019).

Fuqua, W. C., Winans, S. C. & Greenberg, E. P. Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J. Bacteriol. 176, 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.176.2.269-275.1994 (1994).

Dettweiler, M. et al. American civil war plant medicines inhibit growth, biofilm formation, and quorum sensing by multidrug-resistant bacteria. Sci. Rep. 9, 7692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44242-y (2019).

Muhs, A. et al. Virulence inhibitors from Brazilian Peppertree block quorum sensing and abate dermonecrosis in skin infection models. Sci. Rep. 7, 42275. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42275 (2017).

Quave, C. L. et al. Castanea sativa (European Chestnut) leaf extracts rich in ursene and oleanene derivatives block Staphylococcus aureus virulence and pathogenesis without detectable resistance. PLoS ONE 10, e0136486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136486 (2015).

Miller, J. S. In Drug Discovery and Traditional Chinese Medicine: Science, Regulation, and Globalization (ed. Lin, Y.) 33–42 (Springer, Berlin, 2001).

Delgoda, R. & Murray, J. E. In Pharmacognosy (eds Badal, S. & Delgoda, R.) 93–100 (Academic Press, Cambridge, 2017).

Atanasov, A. G. et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 33, 1582–1614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001 (2015).

Bussmann, R. W. et al. Knowledge loss and change between 2002 and 2017—a revisit of plant use of the Maasai of Sekenani Valley, Maasai Mara, Kenya. Econ. Bot. 72, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-018-9411-9 (2018).

Kigen, G., Kamuren, Z., Njiru, E., Wanjohi, B. & Kipkore, W. Ethnomedical survey of the plants used by traditional healers in Narok County, Kenya. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8976937 (2019).

Abbo, C. Profiles and outcome of traditional healing practices for severe mental illnesses in two districts of eastern Uganda. Glob. Health Action. 4(1), 7117. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v4i0.7117 (2011).

THETA. Contributions of Traditional Medicine to Health Care Deliveries in Uganda (Ministry of Health, Public and Private Partnership Office, Kampala, 2001).

Hamilton, A. C., Karamura, D. & Kakudidi, E. History and conservation of wild and cultivated plant diversity in Uganda: forest species and banana varieties as case studies. Plant divers. 38, 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2016.04.001 (2016).

Kalema, J. & Bukenya-Ziraba, R. Patterns of plant diversity in Uganda. Biol. Skr. 55, 331–341 (2005).

Schultz, F., Anywar, G., Wack, B., Quave, C. L. & Garbe, L.-A. Ethnobotanical study of selected medicinal plants traditionally used in the rural Greater Mpigi region of Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 256, 112742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.112742 (2020).

Howard, P. C. Nature Conservation in Uganda’s Tropical Forest Reserves (International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Gland, 1991).

Barbour, M. G., Burk, J. H. & Pitts, W. D. Terrestrial Plant Ecology 2nd edn. (Benjamin Cummings, Menlo Park, 1987).

Robinson, D. A., Monk, A. B., Cooper, J. E., Feil, E. J. & Enright, M. C. Evolutionary genetics of the accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187, 8312–8321. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.187.24.8312-8321.2005 (2005).

Mayville, P. et al. Structure-activity analysis of synthetic autoinducing thiolactone peptides from Staphylococcus aureus responsible for virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1218–1223. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.4.1218 (1999).

Park, J. et al. Infection control by antibody disruption of bacterial quorum sensing signaling. Chem. Biol. 14, 1119–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.08.013 (2007).

Schwan, W. R., Langhorne, M. H., Ritchie, H. D. & Stover, C. K. Loss of hemolysin expression in Staphylococcus aureus agr mutants correlates with selective survival during mixed infections in murine abscesses and wounds. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 38, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0928-8244(03)00098-1 (2003).

Wright, J. S. 3rd., Jin, R. & Novick, R. P. Transient interference with staphylococcal quorum sensing blocks abscess formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 1691–1696. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0407661102 (2005).

Stryjewski, M. E. & Chambers, H. F. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl 5), S368-377. https://doi.org/10.1086/533593 (2008).

Otto, M. Staphylococcus aureus toxins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 17, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2013.11.004 (2014).

Wang, R. et al. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat. Med. 13, 1510–1514. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1656 (2007).

Kasimir, S., Schönfeld, W., Alouf, J. E. & König, W. Effect of Staphylococcus aureus delta-toxin on human granulocyte functions and platelet-activating-factor metabolism. Infect. Immun. 58, 1653–1659 (1990).

Schmitz, F. J., Veldkamp, K. E., Van Kessel, K. P., Verhoef, J. & Van Strijp, J. A. Delta-toxin from Staphylococcus aureus as a costimulator of human neutrophil oxidative burst. J. Infect. Dis. 176, 1531–1537. https://doi.org/10.1086/514152 (1997).

Quave, C. L. & Horswill, A. R. Identification of Staphylococcal quorum sensing inhibitors by quantification of o-hemolysin with high performance liquid chromatography. Quorum Sens. Methods Mol. Biol. 1673, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7309-5_27 (2017).

Muller, A. C. & Kanfer, I. Potential pharmacokinetic interactions between antiretrovirals and medicinal plants used as complementary and African traditional medicines. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 32, 458–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdd.775 (2011).

Philip, K., Mwangi, E., Cheplogoi, P. & Samuel, K. Ethnobotanical survey of antimalarial medicinal plants used in Butebo County, Eastern Uganda. Eur. J. Med. Plants 21, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.9734/EJMP/2017/35368 (2017).

Bunalema, L., Obakiro, S., Tabuti, J. R. & Waako, P. Knowledge on plants used traditionally in the treatment of tuberculosis in Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151, 999–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.020 (2014).

Tabuti, J. R., Kukunda, C. B. & Waako, P. J. Medicinal plants used by traditional medicine practitioners in the treatment of tuberculosis and related ailments in Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 127, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.035 (2010).

Lamorde, M. et al. Medicinal plants used by traditional medicine practitioners for the treatment of HIV/AIDS and related conditions in Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 130, 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.004 (2010).

Wambugu, S. N. et al. Medicinal plants used in the management of chronic joint pains in Machakos and Makueni counties, Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 137, 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.06.038 (2011).

Owibingire, S., Kamya, E. & Singh, K. Misconceptions on causes and management of dental caries: experience from Central Tanzanian Society. Ann. Int. Med. Dent. Res. 4, 18–24. https://doi.org/10.21276/aimdr.2018.4.2.DE5 (2018).

Bussa, N. F. & Belayneh, A. Traditional medicinal plants used to treat cancer, tumors and inflammatory ailments in Harari Region, Eastern Ethiopia. S. Afr. J. Bot. 122, 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2019.03.025 (2019).

Adia, M. M., Emami, S. N., Byamukama, R., Faye, I. & Borg-Karlson, A. K. Antiplasmodial activity and phytochemical analysis of extracts from selected Ugandan medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 186, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.03.047 (2016).

Olila, D., Olwa, O. & Opuda-Asibo, J. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of extracts of Zanthoxylum chalybeum and Warburgia ugandensis, Ugandan medicinal plants. Afr. Health Sci. 1, 66–72 (2001).

Kuglerova, M. et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidative effects of Ugandan medicinal barks. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 3628–3632. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB09.1815 (2011).

Erinoso, S. & Aworinde, D. Ethnobotanical survey of some medicinal plants used in traditional health care in Abeokuta areas of Ogun State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 6, 1352–1362. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJPP12.127 (2012).

Tjeck, O. P., Souza, A., Mickala, P., Lepengue, A. N. & M’Batchi, B. Bio-efficacy of medicinal plants used for the management of diabetes mellitus in Gabon: an ethnopharmacological approach. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 6, 206–217. https://doi.org/10.5455/jice.20170414055506 (2017).

Rakotondrafara, A. et al. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used by the Zafimaniry clan in Madagascar. J. Phytopharmacol. 7(6), 483–494 (2018).

Malan, D. F., Neuba, D. F. & Kouakou, K. L. Medicinal plants and traditional healing practices in Ehotile people, around the Aby Lagoon (eastern littoral of Cote d’Ivoire). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0004-8 (2015).

Nyamukuru, A. et al. Medicinal plants and traditional treatment practices used in the management of HIV/AIDS clients in Mpigi District, Uganda. J. Herbal Med. 7, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hermed.2016.10.001 (2017).

Mukungu, N., Abuga, K., Okalebo, F., Ingwela, R. & Mwangi, J. Medicinal plants used for management of malaria among the Luhya community of Kakamega East sub-County, Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 194, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.050 (2016).

Mba, J. et al. Antidiarrhoeal, antibacterial and toxicological evaluation of Harungana madagascariensis. Sch. Acad. J. Biosci. 5, 230–239. https://doi.org/10.21276/sajb.2017.5.3.18 (2017).

Tankeo, S. B. et al. Antibacterial activities of the methanol extracts, fractions and compounds from Harungana madagascariensis Lam. ex Poir. (Hypericaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 190, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.005 (2016).

Onajobi, I. B. et al. New alpha-glucosidase inhibiting anthracenone from the barks of Harungana madagascariensis Lam. Nat. Prod. Res. 30, 2507–2513. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2015.1115998 (2016).

Kouam, S. F. et al. Prenylated anthronoid antioxidants from the stem bark of Harungana madagascariensis. Phytochemistry 66, 1174–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.03.022 (2005).

Ritchie, E. & Taylor, W. C. The constituents of Harungana madagascariensis Poir. Tetrahedron Lett. 5, 1431–1436. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(01)89507-1 (1964).

Rios, R. et al. Genomic epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREfm) in Latin America: revisiting the global VRE population structure. Sci. Rep. 10, 5636. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62371-7 (2020).

Matlou, D. P. et al. Virulence profiles of vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolated from surface and ground water utilized by humans in the North West Province, South Africa: a public health perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 15105–15114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04836-5 (2019).

Iweriebor, B. C., Obi, L. C. & Okoh, A. I. Virulence and antimicrobial resistance factors of Enterococcus spp. isolated from fecal samples from piggery farms in Eastern Cape, South Africa. BMC Microbiol. 15, 136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0468-7 (2015).

Arias, C. A. & Murray, B. E. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2761 (2012).

Cattoir, V. & Giard, J. C. Antibiotic resistance in Enterococcus faecium clinical isolates. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 12, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.2014.870886 (2014).

Jabbari Shiadeh, S. M., Pormohammad, A., Hashemi, A. & Lak, P. Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in blood-isolated Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Drug Resist. 12, 2713–2725. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S206084 (2019).

Hammerum, A. M. Enterococci of animal origin and their significance for public health. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03829.x (2012).

Stefani, S. et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): global epidemiology and harmonisation of typing methods. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39, 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.030 (2012).

Cong, Y., Yang, S. & Rao, X. Vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a review of case updating and clinical features. J. Adv. Res. 21, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2019.10.005 (2020).

Almeida, G. C. M. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with wound colonization by Staphylococcus spp. and Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized patients in inland northeastern Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 328–328. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-328 (2014).

Kane, T. L., Carothers, K. E. & Lee, S. W. Virulence factor targeting of the bacterial pathogen Staphylococcus aureus for vaccine and therapeutics. Curr. Drug Targets 19, 111–127. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450117666161128123536 (2018).

Alksne, L. E. & Projan, S. J. Bacterial virulence as a target for antimicrobial chemotherapy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11, 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00155-5 (2000).

Khan, R., Petersen, F. C. & Shekhar, S. Commensal bacteria: an emerging player in defense against respiratory pathogens. Front. Immunol. 10, 1203–1203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01203 (2019).

Maeda, T. et al. Quorum quenching quandary: resistance to antivirulence compounds. ISME J. 6, 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.122 (2012).

Clatworthy, A. E., Pierson, E. & Hung, D. T. Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2007.24 (2007).

Borges, A. & Simões, M. Quorum sensing inhibition by marine bacteria. Mar. Drugs 17, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17070427 (2019).

Mogale, M. M. P., Raimondo, D. C. & VanWyk, B. E. The ethnobotany of Central Sekhukhuneland, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 122, 90–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2019.01.001 (2019).

Ochwang’i, D. O. et al. Medicinal plants used in treatment and management of cancer in Kakamega County, Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151, 1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.051 (2014).

Mongalo, N. I. & Makhafola, T. J. Ethnobotanical knowledge of the lay people of Blouberg area (Pedi tribe), Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 14, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0245-4 (2018).

Koduru, S., Grierson, D. & Afolayan, A. Ethnobotanical information of medicinal plants used for treatment of cancer in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Curr. Sci. 92, 906–908 (2007).

Laban, L. T. et al. Experimental therapeutic studies of Solanum aculeastrum Dunal. on Leishmania major infection in BALB/c mice. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 18, 64–71 (2015).

Koduru, S., Grierson, D. S., Van de Venter, M. & Afolayan, A. In vitro antitumour activity of Solanum aculeastrum berries on three carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer Res. 2, 397–402. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijcr.2006.397.402 (2006).

Wanyonyi, A. W., Chhabra, S. C., Mkoji, G., Njue, W. & Tarus, P. K. Molluscicidal and antimicrobial activity of Solanum aculeastrum. Fitoterapia 74, 298–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0367-326X(03)00030-3 (2003).

Aboyade, O., Yakubu, M., Grierson, D. & Afolayan, A. Safety evaluation of aqueous extract of unripe berries of Solanum aculeastrum in male Wistar rats. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 4, 90–97 (2010).

Aboyade, O., Yakubu, M., Grierson, D. & Afolayan, A. Studies on the toxicological effect of the aqueous extract of the fresh, dried and boiled berries of Solanum aculeastrum Dunal in male Wistar rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 28, 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327109354545 (2009).

Koduru, S., Grierson, D. S. & Afolayan, A. Antimicrobial activity of Solanum aculeastrum. Pharm. Biol. 44, 283–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880200600714145 (2008).

Wanyonyi, A. W., Chhabra, S. C., Mkoji, G., Eilert, U. & Njue, W. M. Bioactive steroidal alkaloid glycosides from Solanum aculeastrum. Phytochemistry 59, 79–84 (2002).

Burger, T. et al. Solamargine, a bioactive steroidal alkaloid isolated from Solanum aculeastrum induces non-selective cytotoxicity and p-glycoprotein inhibition. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 18, 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-018-2208-7 (2018).

Miller, J. S. Zulu Medicinal Plants: An Inventory By A. Hutchings with A. H. Scott, G. Lewis, and A. B. Cunningham (University of Zululand) (University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, 1996).

Kibuuka, M. S. & Anywar, G. Medicinal plant species used in the management of hernia by traditional medicine practitioners in Central Uganda. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 14, 289–298 (2015).

Chhabra, S. C. & Mahunnah, R. L. A. Plants used in traditional medicine by hayas of the Kagera region, Tanzania. Econ. Bot. 48, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02908198 (1994).

Tabuti, J. R., Lye, K. A. & Dhillion, S. S. Traditional herbal drugs of Bulamogi, Uganda: plants, use and administration. J. Ethnopharmacol. 88, 19–44 (2003).

Hamill, F. A. et al. Traditional herbal drugs of Southern Uganda, II: literature analysis and antimicrobial assays. J. Ethnopharmacol. 84, 57–78 (2003).

Chidewe, C., Castillo, U. F. & Sem, D. S. Structural analysis and antimicrobial activity of chromatographically separated fractions of leaves of Sesamum angustifolium (Oliv.) Engl. J. Biol. Act. Prod. Nat. 7, 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/22311866.2017.1417057 (2017).

Martin, G. J. Ethnobotany: A Methods Manual. People and Plants International Conservation (Routledge, London, 2004).

Weckerle, C. S. et al. Recommended standards for conducting and reporting ethnopharmacological field studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 210, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.018 (2018).

The Angiosperm Phylogeny, G. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 181, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/boj.12385 (2016).

SERNEC. SouthEast Regional Network of Expertise and Collections. https://sernecportal.org/portal/index.php.

Cockerill, F. et al. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-Third Informational Supplement; M100-S23 (CLSI, Wayne, 2013).

Quave, C. L., Plano, L. R., Pantuso, T. & Bennett, B. C. Effects of extracts from Italian medicinal plants on planktonic growth, biofilm formation and adherence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 118, 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2008.05.005 (2008).

Quave, C. L. & Horswill, A. R. Flipping the switch: tools for detecting small molecule inhibitors of staphylococcal virulence. Front. Microbiol. 5, 706–706. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00706 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Fulbright Fellowship (FS), a Grant from the BMBF—German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (13FH026IX5, PI: LAG and Co-I: FS), and a Grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (R21 AI13656s3, PI: CQ). We acknowledge support for the Article Processing Charge from the German Research Foundation (DFG, 414051096) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Neubrandenburg University of Applied Sciences (HSNB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official view of NIAID, NIH, Fulbright, DFG, HSNB or BMBF. The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank Alex Horswill (UC Denver) for providing the Staphylococcus aureus agr reporter isolates: AH1677, AH430, AH1747, and AH1872. Thanks to research assistants Kristine Kossol, Tidjani Cisse and Tina Seehafer for assisting during the extractions of plant material. Thanks to Micah Dettweiler for assisting in strain maintenance. Thanks to Logan Penniket for proof-reading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S. and G.A. collected and processed the plant material. G.A. prepared herbarium voucher specimens and identified the plant species. F.S. prepared extracts and performed the antibacterial, quorum sensing inhibition and δ-toxin experiments. F.S. and F.C. conducted the cell culture experiments. F.S., J.T.L. and H.T. performed the HPLC analyses. J.T.L. performed and analyzed the LC–MS experiments. F.S., J.T.L. and C.L.Q. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. L.A.G. provided oversight of extraction procedures and fieldwork. C.L.Q. directed the study. All authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schultz, F., Anywar, G., Tang, H. et al. Targeting ESKAPE pathogens with anti-infective medicinal plants from the Greater Mpigi region in Uganda. Sci Rep 10, 11935 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67572-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67572-8

This article is cited by

-

Albizia coriaria Welw ex Oliver: a review of its ethnobotany, phytochemistry and ethnopharmacology

Advances in Traditional Medicine (2023)

-

Going Beyond Host Defence Peptides: Horizons of Chemically Engineered Peptides for Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria

BioDrugs (2023)

-

Isolation and characterization of compounds in ethanolic extract of Albizia coriaria (Welw ex. Oliver) leaves: a further evidence of its ethnomedicinal diversity

Bulletin of the National Research Centre (2022)

-

Antibacterial activity of nanozeolite doped with silver and titanium nanoparticles

Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology (2022)

-

Assessment of the anti-virulence potential of extracts from four plants used in traditional Chinese medicine against multidrug-resistant pathogens

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.