Abstract

Our aim was to evaluate whether fatty liver index (FLI) is associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) development within the Spanish adult population and according to their prediabetes status; additionally, to examine its incremental predictive value regarding traditional risk factors. A total of 2260 subjects (Prediabetes: 641 subjects, normoglycemia: 1619 subjects) from the Di@bet.es cohort study were studied. Socio-demographic, anthropometric, clinical data and survey on habits were recorded. An oral glucose tolerance test was performed and fasting determinations of glucose, lipids and insulin were made. FLI was calculated and classified into three categories: Low (< 30), intermediate (30–60) and high (> 60). In total, 143 people developed diabetes at follow-up. The presence of a high FLI category was in all cases a significant independent risk factor for the development of diabetes. The inclusion of FLI categories in prediction models based on different conventional T2DM risk factors significantly increase the prediction power of the models when all the population was considered. According to our results, FLI might be considered an early indicator of T2DM development even under normoglycemic condition. The data also suggest that FLI could provide additional information for the prediction of T2DM in models based on conventional risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by increased fat storage in form of triglycerides in the liver (exceeding 5% of its weight) in absence of excessive alcohol consumption1. It is the most frequent liver disease in Western countries with an estimated overall worldwide prevalence in the adult population of about 25%2, value that is substantially increased in subjects with type 2 diabetes (T2DM)2. A recent study in the United States population has reported the presence of NAFLD in up to 78–85% of patients with T2DM, based on the use of different non-invasive markers of liver steatosis3. Specifically in Spain, the prevalence of NAFLD has been estimated to be 26% among the adult population4.

NAFLD is associated with several liver disorders, terminal liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma5, cardiovascular disease6 and it is considered as the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome7,8. Additionally, increasing epidemiological evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and T2DM may be linked by insulin resistance9,10,11. This concept would be in line with several studies that have consistently shown that NAFLD is an independent risk factor for prediabetes or T2DM12,13,14. Given the progressive nature of the disease and its risk of adverse consequences, health care providers are strongly advised to screen for NAFLD in all patients with diabetes and to be more proactive in their management11.

The gold standard for diagnosis of NAFLD is the liver biopsy, which is an invasive technique only justified in severe liver disease15. 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) allows a quantification of hepatocellular lipid content and an exact diagnosis of steatosis15, while ultrasound and computed tomography provide semi-quantitative estimations16. These techniques are time-consuming, expensive and often unavailable in the daily routine. As an alternative, several panels or ‘scores’ consisting of combinations of anthropometric and biochemical parameters have been developed for the diagnosis and quantification of steatosis. Among all of them, the fatty liver index (FLI) has gained popularity17,18. FLI is a non-invasive and well-established method for the diagnosis of fatty liver validated against ultrasound17,18,19,20 and MRS21 in both Asian and Western populations. It includes 4 variables: body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, serum triglycerides and serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT)18.

Several previous studies, have reported that FLI is a predictor for the development of T2DM in the general population22,23,24 and in subjects who have an especially higher risk of DM2 (prediabetic status)14,25,26,27. Accordingly, FLI could be potentially useful to further identify those who are at higher risk of conversion to new onset of T2DM in order to initiate primary prevention efforts with aggressive lifestyle management28. Nevertheless, the additive predictive value of FLI beyond the conventional risk factors of T2DM has been investigated less and with inconclusive results23,25. In the same way, it is unclear whether FLI is associated with the development of T2DM in individuals without prediabetes who might be at lower risk for incident T2DM. To our knowledge, only one study performed in a Japanese population has reported the potential utility of FLI as a predictor for T2DM development in subjects without hyperglycemia29.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate whether fatty liver estimated by FLI is associated with the risk of T2DM within the Spanish adult population with and without prediabetes. In addition, we also examined the incremental predictive value of FLI in diagnosing individuals who will develop new-onset T2DM over 7.5 years of follow-up in the Spanish general adult population and according to the prediabetes status.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the population

The baseline characteristics of the subjects according to FLI categories in the overall population and the groups of subjects with and without prediabetes are presented in Table 1. For all the cases, groups of subjects in the low FLI category were younger and with a lower percentage of men than the rest of FLI categories. In general, anthropometric variables, clinical parameters and lifestyle factors were different according to FLI categories for all the studied population groups.

Compared to the low FLI category, individuals in the high FLI category had higher fasting glucose levels (FGL) except in the group with prediabetes, where no differences in FPG according to FLI categories were found. No differences in the family history of T2DM or in the adherence to the Mediterranean diet were found according to FLI categories for any group.

New onset of T2DM

143 people developed T2DM after 7.5 years of follow-up, among them 106 had prediabetes at baseline. The proportions of subjects who develop T2DM were significantly different according to the FLI categories in all the studied groups (Overall population: 1.77% within low FLI category, 4.90% within intermediate FLI category and 13.04% within high FLI category. Subjects with normoglycemia: 0.73% within low FLI category, 2.7% within intermediate FLI category and 5.13% within high FLI category. Subjects with prediabetes: 8.08% within low FLI category, 10.36% within intermediate FLI category and 22.07% within high FLI category. p < 0.001 for all cases measured by a Chi-Square test.). Proportion of subjects who develop T2DM within each FLI category according to sex is showed in Supplementary Table S1.

FLI as a T2DM development biomarker

We analyzed incidence rate ratios (RR) of FLI and each component (BMI, waist circumference, serum triglycerides and GGT) for new-onset of T2DM in overall population. As a result, we found that FLI and its components were significantly associated to incident T2DM (RR[95% CI]: FLI = 1.03[1.02–1.3]; BMI = 1.12[1.09–1.15]; waist circumference = 1.05[1.04–1.06]; triglycerides = 6.90[3.60–13.20] and GGT = 4.08[2.86–5.84]. p < 0.001 in all the cases).

Multivariate analyses for the development of T2DM at 7.5 years of follow-up in overall population (Table 2) and in subjects classified according to their prediabetes status at baseline (Table 3) were also performed. Results from these multivariate models adjusted by different confounding variables showed that the presence of a high FLI category was in all cases a significant independent risk factor for the development of T2DM with a significant p for trend for the increased incidence RR associated with higher FLI categories in overall population (Table 2), and also in subjects under normoglycemia or prediabetes conditions (Table 3). Significant independent associations remained when FLI was considered as continuous variable (Supplementary Table S2).

Separate analyses by sex returned similar results in overall population (Supplementary Table S3). When population is split by prediabetes status, the RR values for the association between FLI and T2DM incidence were similar between men and women in all regression models, both in subjects with normoglicemia and prediabetes (Supplementary Table S4); nevertheless, associations remained significant mainly in the group of women with normoglicemia where the sample size was also higher.

Predictive value of FLI

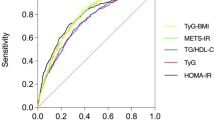

To compare the predictive value of FLI for the risk of new cases of T2DM regarding the individual variables include in its calculation, we performed comparisons of receiver operating (ROC) curves of these prediction models. Analysis of these ROC curves showed that the AUC was significantly increased in the model with FLI versus the models with its components (Supplementary Figure S1).

Additionally, we performed ROC curves for new cases of T2DM of two proposed models which include or not the FLI categories. The first proposed model (PM1) was based on the conventional risk factors for T2DM development age, sex, FGL, background of T2DM, and insulin resistance risk category (HOMA-IR). The second proposed model (PM2) was based on PM1 but excluding HOMA-IR considering the difficulties to determine HOMA values routinely in clinical practice.

The addition of FLI categories to both PM1 and PM2 models in the overall population is shown in Fig. 1. The AUC for predicting future incidence of T2DM significantly increased when FLI was added to both diabetes prediction models (Fig. 1). We also assessed whether the addition of FLI to the conventional T2DM prediction models can improve the predictive ability for new-onset T2DM using NRI and IDI30. We found that the IDI values were − 0.010 (95% CI: − 0.016 to − 0.004, p = 0.01) for the PM1 model, and − 0.016 (95% CI: − 0.027 to − 0.026, p = 0.02) for the PM2 model. Additionally, the category-free NRI were 0.066 (standard error = 0.021, z-score = 2.004, p = 0.045) and 0.07 (standard error = 0.027, z-score = 2.57, p = 0.001) for the PM1 and PM2 models respectively. Thus, the addition of FLI to these basic diabetes risk models correctly reclassified 6.6% and 7% more cases respectively in the overall study population.

Comparison of area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) for incident T2DM in overall population according to adding or not FLI to the conventional T2DM prediction risk models PM1 (age, sex, family history of T2DM, fasting glucose level and insulin resistance risk category) and PM2 (age, sex, family history of T2DM and fasting glucose level).

Alternatively, when the prediabetes status was considered, the inclusion of the FLI categories in the PM1 model slightly increased the AUC with no significant differences independently of the prediabetes status (Fig. 2). However, the inclusion of FLI categories in the model excluding insulin resistance status (PM2) resulted in a significant increment of the AUC in comparison with the model without FLI, both in normoglycemic (Fig. 2A) and subjects with prediabetes (Fig. 2B). NRI and IDI values for the potential predictive improvement associated with these incremented AUCs were not significant.

Comparison of area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) for incident T2DM in subjects with and without prediabetes according to adding or not FLI to the conventional T2DM prediction risk models PM1 (age, sex, family history of T2DM, fasting glucose level and insulin resistance risk category) and PM2 (age, sex, family history of T2DM and fasting glucose level).

No significant differences were found in any of the studied groups comparing PM1vs PM2 AUCs in models with FLI; nor in models without FLI.

Discussion

In this cohort of the Spanish adult population, we found that FLI levels were positively associated with the risk of incident T2DM after 7.5 years follow-up, independently of different risk factors for diabetes such as age, sex, FGL, family history of T2DM, HOMA-IR, plasma lipids, hypertension or lifestyle. We also showed that the association of FLI with the development of T2DM remained within the normoglycemic Spanish population, even though the risk of diabetes in this group was lower. Moreover, we found that models including categorized FLI correctly reclassified a substantial proportion of incident T2DM cases of the Spanish overall population independently of the presence of the HOMA-IR in the prediction models.

Increasing epidemiological evidence suggests that there is a bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and T2DM which may be linked by insulin resistance12,13,14. In relation to this, FLI is not only considered a good marker for fatty liver in clinical practice, but it has also been suggested as a rough clinical estimate of abnormal insulin sensitivity and secretion21.

The majority of previous studies have shown that higher FLI levels might be a predictor of the development of incident T2DM in the general population23,24,27 and in patients with prediabetes14,25,26 independently of different confounding variables. According to these, in our study, in all models the highest FLI category was significantly associated with the development of incident T2DM after 7.5 years in the general population and within subjects with prediabetes. Franch-Nadal et al. have previously published the association of FLI-diagnosed hepatic steatosis with the risk of developing T2DM in the Spanish population with prediabetes at a shorter follow-up period; nevertheless, unlike our investigation, the lack of data on HOMA values did not allow them to disentangle the respective effects of HOMA-IR and FLI on the risk of T2DM development. Contrary to our findings, data from the IT-DIAB study25, in which the association between FLI and T2DM conversion was studied in a sample of 389 subjects with prediabetes from three different French cities, indicated that after including the HOMA levels in their multivariate analysis, the FLI was no longer significantly associated with conversion to new onset of T2DM. This difference could be potentially explained, as some of the authors declared in the study limitations, by their limited sample size and the lack of statistical power to draw adequate mixed models.

Our results also show for the first time that high FLI levels are associated with the risk of T2DM development in normoglycemic subjects from a European population. Moreover, this association was also independent of other confounding variables such as sex, age, baseline FGL, family history of T2DM, lifestyle, hypertension, lipid profile, level of transaminases and insulin resistance risk category. To the best of our knowledge, only one other study has been performed so far assessing the association of FLI levels and incidence of T2DM in normoglycemic subjects29. This study was performed in a Japanese population and concurs with our current results, higher FLI levels were found to be a predictor of incident T2DM in individuals without prediabetes according to a model adjusted by age, systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, smoking and alcohol consumption status. However, unlike our investigation, the impact of insulin resistance on the relationship between FLI and T2DM was not examined in their study.

In our study, FLI was able to significantly increased AUC for the future T2DM compared to the variables included in its calculation; additionally, the incorporation of FLI into traditional T2DM risk prediction models including age, sex, FGL, family background of T2DM, with and without HOMA-IR, significantly improved the prediction AUC of T2DM development after 7.5 years of follow-up in the Spanish general population. Similar results have been reported by Yadav et al.23 in a Japanese population where they also observed that, opposite to the FLI, the addition of BMI and/or waist circumference to the conventional T2DM prediction model did not significantly improve the AUC values. To further explore the added value of FLI as a T2DM predictor, we calculated the specific statistical metrics IDI and NRI, which are known to be more sensitive than AUC for the determination of improvement in the predictive value30. IDI can provide clinical information on increased sensitivity without sacrificing specificity and NRI can provide clinical information by quantifying the improvement. According to our knowledge, only the KoGES-ARIRANG Japanese study has reported information about the incremental predictive value of FLI on the risk of T2DM development with IDI and NRI data23. Similar to this previous work, our current study showed for the overall Spanish population that FLI improved incident T2DM subject reclassification with both significant IDI and NRI, independently of the presence of the HOMA-IR in the prediction models. Additionally, when comparing the ROC curves of models including or not the insulin resistance risk category, non-significant differences for better predicting T2DM development were found. Altogether, these data suggest that for the general Spanish population, FLI not only act as an additional contributor to predicting incident T2DM when applied with these conventional risk factors, but it could also be considered as an effective and efficient alternative to HOMA determination in clinical practice to evaluate the risk of T2DM development avoiding the cost of the circulating insulin determination.

When comparing AUCs from the ROC curves in the groups of subjects according to the prediabetes status, the improvement resulting from the inclusion of FLI in the prediction models was only significant when these models excluded HOMA-IR category. Nevertheless, non-significant reclassification improvement estimated by NRI nor IDI statistics was found after the inclusion of FLI in any of the models. No previous data have been published so far regarding the quantification of the predictive value of FLI in the development of T2DM by either using NRI or IDI methods according to the prediabetes status.

Our study presents some limitations. Even if FLI was first proposed as a good readout of hepatic steatosis18, we were not able to confirm hepatic steatosis in our population as relevant imaging data. Subjects with severe diseases such as hepatitis were excluded from the cohort; however, participants were not screened for other different forms of liver disease. Although participation in the follow-up was 66%, the possible participation bias was minimal31; nevertheless, the limited sample size when the overall population is split according to prediabetes status might be the cause of the lack of significant differences between AUCs and NRI and IDI values. Alternatively, sample size might be also limited to detect significant associations in the analysis men and women separately when overall population is split by the prediabetes status (especially in the group of subjects with prediabetes); nevertheless, RR for the association between categories of FLI and T2DM incidence were similar between men and women, which let us to believe that there were not differences between men and women and the lack of significant associations was mainly due to a limited sample size; to avoid possible interferences related to the sex, we included it as confounding variable in all the multivariate models. Prescription drugs are a well-known cause of hepatotoxicity and although the use of some of the most known steatogenic drugs has been considered in the models adjustment, the list of these medications is long and heterogeneous and it was impossible to assess the effects of other medications. There could also be an underdiagnosis in the declared interpretation of the subjects in relation to their pharmacological treatments and this cannot be ruled out. As it is common in epidemiological studies, HOMA index was used to estimate insulin resistance instead of performing the clamp method. HOMA-IR index has been validated against the gold-standard hyperinsulinaemic euglycaemic clamp (an invasive, intensive and technically difficult procedure), and is considered a reliable index to assess insulin sensitivity in epidemiological studies which assess “in vivo” insulin sensitivity in humans32. Even that in our results FLI showed a significantly higher predicting T2DM AUC values than its individual components, and although previous investigations have reported that the addition of BMI and/or waist circumference to conventional T2DM prediction model did not significantly improve the AUC values23; it is likely that the improvement observed in the AUC after the incorporation of FLI into the MP1 and MP2 models, might be related to the variables included in the FLI calculation, then this result should be carefully considered.

The main strength of the study is that the data were obtained from a large national wide-cohort, with a considerable duration of the follow-up and substantial number of events. Most of the participants underwent an OGTT to diagnose T2DM or prediabetes, and in the follow-up, HbA1c was also used, which guarantees the capture of most of the incident T2DM.

In conclusion, data gathered from this national cohort demonstrated an independent association between the high FLI category and the risk of incident T2DM. Our results also indicate that FLI, a simple surrogate measure of hepatic steatosis, may be considered as an early indicator of T2DM not only in both the general population and subjects with prediabetes, but also in subjects with normal glucose levels. Our current investigation also suggest that FLI might provide additional information for future T2DM to prediction models including the conventional risk factors sex, age, FGL and insulin resistance risk category. In addition, this index might be useful as an alternative to HOMA in clinical practice to evaluate future T2DM risk. Further investigations are needed to confirm the predictive value of FLI in groups of individuals with and without prediabetes, as well as to generalize the value of this risk-scoring tool for predicting incident T2DM.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

Samples and data were based on the population-based, cohort study Di@bet.es epidemiological trial.

The initial cross-sectional study of the Di@bet.es was undertaken in 2008–2010 from a random cluster sampling of the Spanish population33. The Di@bet.es study sample consisted of 5072 subjects more than 18 years old, randomly selected from National Health System registries distributed into 100 clusters. Subjects with severe disease such as cancer or hepatitis were excluded by protocol. The Di@bet.es cohort was re-evaluated in 2016–2017 (the follow-up time was 7.5 ± 0.6 years) and finally 2408 subjects completed the follow-up. Detailed information on the methodology of the Di@bet.es cohort study has been previously described31.

For the present sub-study only followed up participants at risk of T2DM (who had not T2DM at baseline) and from which FLI levels were possible to calculate were included in the analyses (n = 2260). The study population was classified according to the presence (n = 641) or absence (n = 1619) of prediabetes at baseline, which was defined as having FGL ≥ 100 mg/dl and/or post OGTT glucose level ≥ 140 and < 200 mg/dl.

The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (WHO 2011) of the Word Medical Association. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was approved by the Ethics and Clinical Investigation Committee of the Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga (Malaga, Spain) in addition to other regional ethics and clinical investigation committees all over Spain.

Data collection and laboratory measurements

In both phases of the study, the participants were invited to attend an examination visit at their health centre with a nurse specially trained for this project. Information was collected using an interviewer administered structured questionnaire, followed by a physical examination and blood sampling.

For the present study the anthropometric and sociodemographic variables considered were: age, sex, weight, waist, family history of T2DM; educational level (classified as unlettered, attendance to primary or high school, and university); alcohol consumption (never: no alcohol consumption, low: < 1 serving/week, moderate: between 1 serving/week and 2 servings/day for men and 1 serving/day for women, and high: > 2 servings/day for men and over 1 serving/day for women); adherence to the Mediterranean diet (a 14-point Mediterranean diet score was calculated31 and the cut-off for considering adherence was over 8 points in the score); physical activity (classified as low, moderate and high levels according to the IPAQ questionnaire34); smoking habits (current smokers vs former/never been smokers). The use of steatogenic medications35 (amiodarone, methotrexate, tamoxifen, fluoxetine, valproic acid, acetylsalicylic acid or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) has been also considered.

Also, clinical variables such as blood pressure levels, fasting levels of glucose, insulin and lipid profile (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein and triglycerides (TAG)) and transaminases (GGT, aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) were considered.

BMI was calculated. Insulin resistance was estimated by the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA)36, and the HOMA 75th percentile of our population excluding subjects with T2DM was calculated as the insulin resistance risk category (HOMA-IR).

FLI calculation

The FLI levels were calculated as a surrogate marker of hepatic steatosis based on the measures of TAG, GGT, BMI and waist circumference, using the formula described18. FLI values (ranging from 0 to 100) were also classified into three categories: low FLI (levels < 30), intermediate FLI (levels between 30 and 60) and high FLI (levels > 60), as it was established to rule out (low FLI category) and confirm (high FLI category) the presence of NAFLD18.

Definition of new cases of T2DM

New cases of T2DM at follow up were diagnosed as fasting serum glucose equal or higher than 126 mg/dl or 2 h post OGTT equal or higher than 200 mg/dl or HbA1c equal or higher than 6.5% or use of glucose-lowering medication at the follow-up examination37.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD, or proportions. Differences in baseline variables according to FLI categories were measured by ANOVA adjusted by sex, age and BMI or Chi-square test. Variables not following a normal distribution were log-transformed to perform the ANOVA analyses.

Incidence rate ratios of T2DM according FLI categories were calculated in the overall population and in the group of subjects with and without prediabetes using Poisson Robust Regression models38 adjusted by different potential confounders (age, sex, FGL, family history of T2DM, HOMA-IR, physical activity, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, AST and ALT, steatogenic medications, alcohol consumption, educational level, hypertension and/or serum lipids levels).

The discrimination power of the proposed models with and without FLI was tested by ROC curves analysis. Differences in the ROC curves were tested by the Delong’s test. Furthermore, we used net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination index (IDI)30 to quantify the improvement in reclassification and sensitivity based on the addition of FLI to proposed models including the conventional risk factors for prediction of incident T2DM age, sex, family history of T2DM, FGL, with and without HOMA-IR.

Analyses were made using SPSS v20 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

References

LaBrecque, D. R. et al. World gastroenterology organisation global guidelines. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000116 (2014).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 71, 793–801 (2019).

Ciardullo, S., Sala, I. & Perseghin, G. Screening strategies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes: Insights from NHANES 2005–2016. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 167, 108358 (2020).

Caballería, L. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with the presence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in an adult population in Spain. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 22, 24–32 (2010).

Serfaty, L. & Lemoine, M. Definition and natural history of metabolic steatosis: Clinical aspects of NAFLD, NASH and cirrhosis. Diabetes Metab. 34, 634–637 (2008).

Anstee, Q. M., Targher, G. & Day, C. P. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 330–344 (2013).

Yki-Järvinen, H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2, 901–910 (2014).

Ballestri, S. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with an almost twofold increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 31, 936–944 (2016).

Targher, G., Marchesini, G. & Byrne, C. D. Risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Causal association or epiphenomenon?. Diabetes Metab. 42, 142–156 (2016).

Smith, G. I. et al. Insulin resistance drives hepatic de novo lipogenesis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Investig. 130, 1453–1460 (2020).

Bril, F. & Cusi, K. Management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: A call to action. Diabetes Care 40, 419–430 (2017).

Zelber-Sagi, S. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease independently predicts prediabetes during a 7-year prospective follow-up. Liver Int. 33, 1406–1412 (2013).

Hazlehurst, J. M., Woods, C., Marjot, T., Cobbold, J. F. & Tomlinson, J. W. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes. Metabolism 65, 1096–1108 (2016).

Nishi, T., Babazono, A., Maeda, T., Imatoh, T. & Une, H. Evaluation of the fatty liver index as a predictor for the development of diabetes among insurance beneficiaries with prediabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. 6, 309–316 (2015).

Baršić, N., Lerotić, I., Smirčić-Duvnjak, L., Tomašić, V. & Duvnjak, M. Overview and developments in noninvasive diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 3945–3954 (2012).

Webb, M. et al. Diagnostic value of a computerized hepatorenal index for sonographic quantification of liver steatosis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 192, 909–914 (2009).

de Alwis, N. M. W., Anstee, Q. M. & Day, C. P. How to diagnose nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Dis. 34(Suppl 1), 19–26 (2016).

Bedogni, G. et al. The fatty liver index: A simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 6, 33 (2006).

Yang, B. L. et al. External validation of fatty liver index for identifying ultrasonographic fatty liver in a large-scale cross-sectional study in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 10, e0120443 (2015).

Koehler, E. M. et al. External validation of the fatty liver index for identifying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a population-based study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 1201–1204 (2013).

Kahl, S. et al. Comparison of liver fat indices for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. PLoS ONE 9, e94059 (2014).

Jäger, S. et al. Association between the fatty liver index and risk of type 2 diabetes in the EPIC-potsdam study. PLoS ONE 10, e0124749 (2015).

Yadav, D. et al. Fatty liver index as a simple predictor of incident diabetes from the KoGES-ARIRANG study. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e4447 (2016).

Jung, C. H. et al. Assessment of the fatty liver index as an indicator of hepatic steatosis for predicting incident diabetes independently of insulin resistance in a Korean population. Diabet. Med. 30, 428–435 (2013).

Wargny, M. et al. Fatty liver index is a strong predictor of changes in glycemic status in people with prediabetes: The IT-DIAB study. PLoS ONE 14, e0221524 (2019).

Franch-Nadal, J. et al. Fatty liver index is a predictor of incident diabetes in patients with prediabetes: The PREDAPS study. PLoS ONE 13, e0198327 (2018).

Balkau, B. et al. Nine-year incident diabetes is predicted by fatty liver indices: The French D.E.S.I.R. study. BMC Gastroenterol. 10, 56 (2010).

Association, A. D. 3. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 43, S32–S36 (2020).

Hirata, A. et al. Fatty liver index predicts incident diabetes in a Japanese general population with and without impaired fasting glucose. Hepatol. Res. 48, 708–716 (2018).

Pencina, M. J., D’Agostino, R. B., D’Agostino, R. B. & Vasan, R. S. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat. Med. 27, 157–172 (2008).

Rojo-Martínez, G. et al. Incidence of diabetes mellitus in Spain as results of the nation-wide cohort di@bet.es study. Sci. Rep. 10, 2765 (2020).

Bonora, E. et al. Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: Studies in subjects with various degrees of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 23, 57–63 (2000).

Soriguer, F. et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose regulation in Spain: The Di@bet.es study. Diabetologia 55, 88–93 (2012).

Craig, C. L. et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381–1395 (2003).

Aller, R. et al. Consensus document. Management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Clinical practice guideline. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 41, 328–349 (2018).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419 (1985).

Association, A. D. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 43, S14–S31 (2020).

Zou, G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159, 702–706 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Our most sincere thanks to Isabel Ramis for her help at all times in the organisation of the study. Our profound appreciation goes to the primary care managers and personnel of the participating health centres, and very especially to L Forga, F Casanueva, JJ Alemán, J Marzo, JM Millaruelo, J García-Rotllán, MA Ayuso, MB Ballesteros, L Jolín, M Moreiras, J Parra, C Jiménez, and MJ Gamero. To all the fieldworkers, nurses, and technicians, (R Badia, CM Bixquert, A Cobo, O Fullaondo, I Urrutia, TM González, J Trabal, JJ Jiménez, C Martín), without whose work the study would not have been possible. We are indebted to the staff of the UGC of Laboratories of the Hospital Regional Universitario of Málaga, for their invaluable technical assistance. We wish to acknowledge the kind collaboration of the Spanish Diabetes Society. We are grateful to Richard Carlson for help with the English language version of the manuscript. We are very grateful to Patricia González, for her help with the databases, and to all the people who voluntarily participated in the study. We are indebted to the Biobank of the Hospital Regional Universitario of Malaga-IBIMA and CIBERDEM Biorepository (IDIBAPS Biobank), integrated in the Spanish National Biobank Network, for the samples management.

Funding

This investigation has been supported by CIBERDEM (Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad-ISCIII), Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad-ISCIII, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (research Grants PI18/01165, PI17/02136, PI14/00710, PI14/01104, PI14/00970, PI14/00874, PIE14/00031) and cofunding by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “A way to build Europe”. LifeScan España (Madrid, Spain) kindly donated the glucometers and test strips for capillary glucose measurements. Cristina Maldonado-Araque is a researcher in the ‘Rio Hortega’ program (CM19/00186) financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Gemma Rojo-Martinez belongs to the Nicolás Monardes research program of the Consejería de Salud (C-0060-2012; Junta de Andalucía, Spain).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: G.R.-M., S.V., F.S., J.G., S.G., J.F.-N., E.D., F.J.C., L.C. and A.C. Acquisition of data: J.V., I.U., E.O., P.O., E.M., A.L.-S., E.M., T.G.-F., R.G., A.G., S.G.-S., E.G.-E., J.L.G., C.C., R.B. and G.A.-V. Analysis and interpretation of data: E.G.-E. and G.R.-M. Draft the article: E.G.-E. Review for important intellectual content: E.G.-E., S.V., F.S., J.V., I.U., E.O., P.O., E.M., A.L.-S., E.M., T.G.-F., R.G., A.G., S.G.-S., J.L.G., C.C., R.B., G.A.-V., J.G., S.G., A.C., E.D., F.J.C., L.C., G.R.-M. and J.F.-N. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. G.R.-M. is the guarantor of this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Eduard Montanya has been on advisory boards, has received consulting fees, speaker honoraria or research support from Astra Zeneca, Menarini Laboratories, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, NovoNordisk and Sanofi. None of the other authors declare having financial or not financial competing interests, related to this work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Appendix

Appendix

Di@bet.es-incidence Study Group:

G. Rojo-Martínez, F. Soriguer, S. Valdés, N. Colomo, C. Maldonado, E. García-Escobar, A. Lago-Sampedro and S. García-Serrano (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas [CIBERDEM]; UGC Endocrinología y Nutrición, Hospital Regional Universitario, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Málaga [IBIMA], Malaga, Spain), A. Goday (Servicio de Endocrinología y Nutrición, Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain), E. Bordiú (Laboratorio de Bioquímica, Hospital Universitario San Carlos, Madrid, Spain), A. Calle-Pascual (Servicio de Endocrinología y Nutrición, Hospital Universitario San Carlos, Madrid, Spain and CIBERDEM), L. Castaño and I. Urrutia (CIBERDEM; Unidad de Investigación, Hospital Universitario Cruces, Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea [UPV/EHU], Baracaldo, Vizcaya, Spain), C. Castell (Servicio de Prevención enfermedades crónicas no transmisibles, Departamento de Salud. Barcelona, Spain, E. Delgado and E. Menéndez (Servicio de Endocrinología y Nutrición, Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias, Spain), J. Franch-Nadal (Equipo de Atención Primaria Raval Sud, Institut Català de la Salut, Red GEDAPS [Grupo de Estudio de la Diabetes en Atención Primaria de la Salud], Unitat de Suport a la Recerca, Institut d’Investigació en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol, Barcelona, Spain), S. Gaztambide (CIBERDEM; Servicio de Endocrinología y Nutrición, Hospital Universitario de Cruces, UPV/EHU, Baracaldo Vizcaya, Spain), J. Girbés (Unidad de Diabetes, Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Valencia, Spain), R. Gomis (CIBERDEM; IDIBAPS, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain), E. Montanya (Bellvitge Hospital-IDIBELL, University of Barcelona, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain), E. Ortega (CIBEROBN; IDIBAPS, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain), I. Ramis (CIBERDEM, Spain), J. Vendrell (CIBERDEM; Rovira i Virgili University; Servicio de Endocrinología y Nutrición, Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII, Institut d’Investigacions Sanitàries Pere Virgili, Tarragona, Spain).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Escobar, E., Valdés, S., Soriguer, F. et al. Fatty liver index as a predictor for type 2 diabetes in subjects with normoglycemia in a nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep 11, 16453 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95546-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95546-x

This article is cited by

-

Fatty liver index as a predictor for incident type 2 diabetes in community-dwelling adults: longitudinal findings over 12 years

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.