Abstract

The influence of socioeconomic status (SES) on access to standard chemotherapy and/or monoclonal antibody therapy, and associated secular trends, relative survival, and excess mortality, among diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients is not clear. We conducted a Hong Kong population-based cohort study and identified adult patients with histologically diagnosed DLBCL between 2000 and 2018. We examined the association of SES levels with the odds and the secular trends of receipt of chemotherapy and/or rituximab. Additionally, we estimated the long-term relative survival by SES utilizing Hong Kong life tables. Among 4017 patients with DLBCL, 2363 (58.8%) patients received both chemotherapy and rituximab and 740 (18.4%) patients received chemotherapy alone, while 1612 (40.1%) and 914 (22.8%) patients received no rituximab or chemotherapy, respectively. On multivariable analysis, low SES was associated with lesser use of chemotherapy (odd ratio [OR] 0.44; 95% CI 0.34–0.57) and rituximab (OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.32–0.52). The socioeconomic disparity for either treatment showed no secular trend of change. Additionally, patients with low SES showed increased excess mortality, with a hazard ratio of 2.34 (95% CI 1.67–3.28). Improving survival outcomes for patients with DLBCL requires provision of best available medical care and securing access to treatment regardless of patients’ SES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) globally, constituting 25–40% of all cases in different geographic regions1,2,3,4. The median survival time without active treatment is less than 1 year5. However, with effective modern therapeutic strategies, a 5-year survival exceeding 60–65% is achieved, according to US population-based data1,6.

Despite advancements in treatment, the role of socioeconomic status (SES) on access to effective treatment among DLBCL patients remains controversial. In a study using the National Cancer Database from the United States on patients with DLBCL, those with low SES were significantly less likely to have received chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy7. However, in another population-based study on patients with DLBCL from the Netherlands, which offers free access to health care, no disparities in treatment and survival were observed in patients with low SES8. Hong Kong has a healthcare system that offers both public and private medical care options, akin to that in countries such as United Kingdoms and Singapore9,10. It remains unclear whether optimal treatment is provided across socioeconomic groups.

An improved understanding of the socioeconomic disparities in access to treatment can provide insight into development of innovative strategies that extend effective therapies to more patients and improve survival. We aimed to determine the association between SES and access to therapy, its secular trend, as well as the long term DLBCL relative survival and excess mortality in a population-based study from Hong Kong.

Materials and methods

Population, settings and data

Data were retrieved from the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS), which is a territory-wide electronic database operated by the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. The Hospital Authority is the sole public healthcare service provider and covers approximately 90% of all medical care in Hong Kong, which has a population of around 7.5 million11. Data, including demographics, hospitalizations, diagnoses, treatment, and causes, times, and dates of death, are recorded in CDARS. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision was used for disease coding. Previous studies have demonstrated positive and negative predictive values exceeding 90%12,13. High-quality population-based studies have been conducted based on the data retrieved from CDARS13,14,15.

We identified patients with DLBCL who were histologically diagnosed in both inpatient and outpatient settings between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2018 from CDARS. The Research Ethics Committee, New Territories West Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong approved this study and waived patient consent requirement (reference no: NTWC/REC/19085). This research project was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Figure 1 shows the case selection flowchart and the final number of patients who constituted the study population16. Patients were excluded if they had uncertain demographic data or younger than 18 years. The receipt of systemic treatment (therapies that potentially affect the entire body) was defined as either having received chemotherapy and/or rituximab. These systemic treatments might be used alone or in combination with radiotherapy.

Variables included in the analysis

We included the following factors that potentially are associated with both the probability of receipt of systemic treatment and patient’s SES: DLBCL patient’s age at diagnosis, sex, comorbidity status, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and year of diagnosis (categorized into 4 similarly sized year ranges). We dichotomized age (> 60 years versus ≤ 60 years) and serum LDH (elevated vs normal, local cut-off value 250 units per liter) according to the DLBCL prognostic scoring system (i.e., the International Prognostic Index)17.

SES was defined based on the need for comprehensive social security assistance (CSSA). CSSA is a basic welfare scheme in Hong Kong that provides supplementary payments to households that cannot support themselves financially18. The scheme aims to bring the income of such individuals and families up to a prescribed level to meet their basic needs of living. The CSSA recipients are also subsidized in medical care. We extracted information regarding this medical financial assistance at household level as a surrogate for SES.

Comorbid conditions was measured using the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Supplementary Method S1)19,20.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for demographics and RCS-modified Charlson score, serum LDH, year of diagnosis were generated for the DLBCL patients. Continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile ranges and compared using the rank-sum test, while categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared using the chi-squared test to describe the differences between SES groups. Factors associated with the initiation of systemic treatment (i.e., chemotherapy and/or rituximab) were evaluated by univariate and multivariate generalized linear regression models using a binomial family and logit link21. The multivariate models were adjusted for SES, age at lymphoma diagnosis (> 60 years vs ≤ 60 years), sex (male vs female), RCS Comorbidity score, serum LDH (elevated vs normal), and year of diagnosis. To explore the temporal trends in the odds of the initiation of systemic treatment by SES we developed a second multivariate model including all the above covariates plus the interaction between the SES and the year of diagnosis. The goodness of fit for the main models was assessed based on the analysis of the residuals and the deviance statistic21. Then, the marginal probabilities of having received systemic treatment over time by SES status were calculated from the predictions of the fitted models and averaged over the observed values of the covariates in the analyses. They are interpreted as the contrast in the mean predicted probability of systemic treatment for those DLBCL patients with low versus high SES over time22,23. Finally, we evaluated the long-term excess mortality and relative survival of DLBCL patients accounting for the competing risk of death for other causes by SES at 15 years (see Supplementary Method S2). We used Stata v.16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, U.S.) for statistical analyses24.

Results

The characteristics of the analyzed DLBCL cohort (N = 4017) are detailed in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 65 years (interquartile range 54–76 years) and 55.9% were male. As of September 30, 2019, the median follow-up time from index date for the entire lymphoma cohort was 6.9 years (minimum 0.8 to maximum 15.0 years). Overall, 1848 patients died during the study period and we there were 18,836 person-years of follow-up. Among 4017 patients, 2363 (58.8%) received both chemotherapy and rituximab, and 740 (18.4%) received chemotherapy alone, while 1612 (40.1%) and 914 (22.8%) received no rituximab or chemotherapy, respectively. Collectively, patients who had high SES were younger (median age 64 years vs. 75 years for high vs. low SES, respectively, rank-sum test p < 0.001) and had less comorbidities (Chi-square test p < 0.001). Older patients generally had more comorbidities (Supplementary Table S1).

On univariate analysis (Table 1), older age at diagnosis, low SES, RCS co-morbidity scores ≥ 2, elevated LDH, and earlier calendar year of diagnosis were associated with lower likelihood of receipt of chemotherapy and/or rituximab.

In the multivariate regression models (Table 2), low SES was associated with a significantly lower odds of receiving any chemotherapy (OR 0.44; 95% CI 0.34–0.57; p < 0.001) or rituximab (OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.32–0.52; p < 0.001). Patients who were above 60 years of age, and had elevated LDH were also independently less likely to receive chemotherapy or rituximab. Additionally, patients with RCS comorbidity score ≥ 2 were less likely to receive chemotherapy (OR 0.80; 95% CI 0.64–0.99; p = 0.044), and male patients were less likely to receive rituximab (OR 0.8; 95% CI 0.68–0.93; p = 0.004). Patients diagnosed in recent years were more likely to receive either treatment. We found no evidence of temporal change in the socioeconomic gap on the odds of receiving chemotherapy and rituximab during the analyzed period (Supplementary Table S2). The marginal probability that a patient in low and high SES received chemotherapy were 64.7% and 68.7%, respectively in 2000–2004; the probabilities increased to 67.1% and 83.8%, respectively in 2015–2018 (Fig. 2a). For rituximab, the marginal probability for lower and higher SES were 16.4% and 23.1% respectively in 2000–2004, and the probabilities increased to 60.1% and 77.8% respectively in 2015–2018 (Fig. 2b). The adjusted odds ratios of rituximab use in 2015–2018 were 0.76 (95% CI 0.43–1.33; p = 0.334), 3.12 (95% CI 1.70–5.75; p < 0.001), and 8.04 (95% CI 2.85–22.70; p < 0.001), when compared with years 2010–2014, 2005–2009, and 2000–2004 respectively.

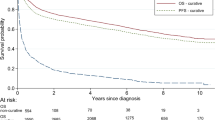

There was also strong evidence of social inequalities in relative survival by SES (Fig. 3). Compared with DLBCL patients with high SES (as baseline group), those with low SES showed an increased excess mortality (EM) risk at 15 years after cancer diagnosis (hazard ratio 2.34, 95% CI 1.67–3.28, p < 0.001). The 15-year probability of relative survival for low and high SES was 34.8% (95% CI 26.8–45.2%) and 59.9% (95% CI 57.5–62.4%) respectively. Supplementary Figure S1 and Table S3 show the cumulative incidence of mortality under the overall survival and the relative survival framework respectively. We detected an increasing survival gap between patients with high and low SES over time.

Relative survival curves of DLBCL by SES groups, produced under the framework of relative survival using Hong Kong life tables, Hong Kong, 2000–2018 (N = 4017). The light grey bands represent the 95% confidence interval bands. CI confidence interval, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, SES socioeconomic status.

Discussion

In this population-based study, we found evidence of disparity related to SES for access to cancer treatment amongst DLBCL patients in Hong-Kong. After controlling for age, number of co-morbidities and other factors, SES remained significantly associated with the odds of receiving systemic therapy. Patients with a low SES had a 56% lower odds of receiving chemotherapy, and a 59% lower odds of receiving rituximab, compared with patients with a higher SES.

The existence of SES disparities in the use of cancer treatment and in mortality among NHL patients have been reported in many US studies7,25,26,27. In countries with a universal or near-complete health care coverage system, discrepancy in SES in access to treatment and survival in NHL patients are more controversial. A UK population-based study using area-based socioeconomic status revealed no significant socioeconomic variations across treatment access and survival outcomes28. However, in a Danish population-based study socioeconomic inequality in survival time among patients with NHL were detected by using individual-level markers of SES, despite no association between education or income and receipt of chemotherapy or immunotherapy was found29,30. The results from our study are distinct that we have found a SES disparity in receiving chemotherapy and rituximab in an Asian city where patients have both public and private care options. Furthermore, SES disparities in the access to treatment are associated with differences in long-term DLBCL survival estimates. The discrepancy in treatment might be explained by the inadequate insurance coverage and inability to cover contributing costs in care despite having subsidized health care in Hong Kong, resulting in inequalities in health care access25,27. We classified households who have financial hardship as having a low SES, while other studies variably assessed individual SES such as personal income and education level29,30, and ecological SES measures such as census-tract of residential area and neighborhood income and education level7,8,25,31,32. A possible reason for the variation in results among studies could be related to different definitions of SES among studies. Individual SES may relate to health behaviors including recognition of symptoms and adherence to treatment33, while aggregated measures of SES may be associated with availability of social and emotional support from peers or relatives, and ease of access to healthcare34,35. One should be careful to generalize our findings to their populations, and have to consider the peculiar organizational and geographic aspects of the structure of their health care system.

In our study, patients with significant comorbidity (RCS ≥ 2) were more commonly found in low SES group. These are consistent with findings from epidemiological studies8,36. We found that RCS ≥ 2 was significantly associated with a lower odd of receiving chemotherapy, but not rituximab. The presence of comorbidity that may interfere with intensive treatment and possible inequalities in treatment. Other hypotheses for patients with low SES having a lower chance of receiving treatment and shorter survival time include more advanced disease upon diagnosis29, inadequate long-term follow-up for these patients, and patient factors such as poorer nutritional status which might adversely affect treatment tolerance and subsequent survival. Further studies are necessary to assess the interaction between comorbidity and other patient-level variables such as race, nutrition, social support, emotional support, and informational support from family and health care providers on DLBCL treatment selection, in the context of the local healthcare system. It is notable, however, that the association between low SES and lower odds of receiving systemic therapy remains significant after controlling for RCS. We also found male patients to be significantly less likely to receive rituximab. A possible explanation could be a higher prevalence of hepatitis B infection among men37,38, affecting their eligibility for rituximab due to physician’s concern of the risk of hepatitis B reactivation39. The provision of prophylactic hepatitis B anti-viral agent was not mandatory and was based on self-pay system in public hospital until the recent 10 years or so40. However, we lack the data on the prevalence of hepatitis B and use antiviral prophylaxis in our cohort for exploring the relationship between the use of rituximab and anti-viral protection. The use of rituximab in our cohort has increased with time and stabilized from 2010 to 2014 onward, this could be related to start of subsidy program for the drug by government since late 200841. Age beyond 60 years was inversely associated with receipt of treatment, this corroborated with previous findings42,43,44,45,46,47,48. Older patients generally have more comorbidities compared to younger patients (Supplementary Table S3) and poorer performance status48,49. Oncologists may steer away from recommended treatment for older patients due to a perception of decreased treatment tolerance and increased side effects, or a preference for avoiding toxicity to preserve quality of life50,51.

Our study has several limitations. The registry database is such that there is a lack of detailed information on lymphoma and its treatment such as stage at diagnosis, performance status, and the number of cycles of systemic treatments. Similar to other electronic medical record database studies, we also do not have data on such lifestyle factors as physical activity level and diet, and we were unable to quantify the effects of social support from peer and family on the treatment selections52. However, where possible we adjusted for components of the International Prognostic Index for DLBCL (age and serum LDH) as covariates in the regression models. We did not have information of SES in life tables, it is possible that we have underestimated the relative survival. Despite limitations, our study has several strengths. First, we analyzed a reasonably large and homogeneous Asian cohort over an almost 20-year time period. This allowed us to examine and account for the time trend of diffusion of treatment. Second, many population-based studies suffered from the effects of potential misclassification and under-reporting previously described in cancer registry studies53,54. Ascertainment of patients for this study was based on a diagnosis of DLBCL being rendered when the patient received care in outpatient or inpatient settings. This would reduce the possibility of selection bias because patients who are older, with more aggressive disease are more frequently diagnosed in inpatient setting55.

In this Asian population-based study involving adult DLBCL patients, we found that patients with low SES were less likely to receive chemotherapy and rituximab, in a region where the healthcare system is a mix of public and private medical options. Furthermore, low SES among DLBCL patients was associated with an increased excess mortality and reduced relative survival compared to those DLBCL patients with higher SES. Socioeconomic disparities on access to DLBCL treatment may contribute to the inferior survival estimates among patients with low SES. Improving cancer outcomes for patients with lymphoma requires provision of best available medical care and securing access to treatment regardless of patients’ SES. Further studies are needed to evaluate the barriers to cancer treatment among socioeconomically disadvantaged DLBCL patients in Hong-Kong.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Teras, L. R. et al. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 443–459. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21357 (2016).

Li, S., Young, K. H. & Medeiros, L. J. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Pathology 50, 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2017.09.006 (2018).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 (2018).

Miranda-Filho, A. et al. Global patterns and trends in the incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Causes Control 30, 489–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01155-5 (2019).

Flowers, C. R., Sinha, R. & Vose, J. M. Improving outcomes for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. CA Cancer J. Clin. 60, 393–408. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20087 (2010).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (version 3.2020). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf. Accessed on April 1, 2021.

Flowers, C. R. et al. Disparities in the early adoption of chemoimmunotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 21, 1520–1530. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-12-0466 (2012).

Boslooper, K. et al. No outcome disparities in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and a low socioeconomic status. Cancer Epidemiol. 48, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2017.04.009 (2017).

Doyle, Y. & Bull, A. Role of private sector in United Kingdom healthcare system. BMJ 321, 563–565. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7260.563 (2000).

Pocock, N. S. & Phua, K. H. Medical tourism and policy implications for health systems: A conceptual framework from a comparative study of Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia. Glob. Health 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-7-12 (2011).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 (2003).

Wong, O. F., Ho, P. L. & Lam, S. K. Retrospective review of clinical presentations, microbiology, and outcomes of patients with psoas abscess. Hong Kong Med. J. 19, 416–423. https://doi.org/10.12809/hkmj133793 (2013).

Chan, E. W. et al. Prevention of dabigatran-related gastrointestinal bleeding with gastroprotective agents: A population-based study. Gastroenterology 149, 586-595.e583. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.002 (2015).

Chiu, S. S., Lau, Y. L., Chan, K. H., Wong, W. H. & Peiris, J. S. Influenza-related hospitalizations among children in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 2097–2103. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020546 (2002).

Cheung, K. S., Seto, W. K., Fung, J., Lai, C. L. & Yuen, M. F. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cholangitis in the Chinese: A territory-based study in Hong Kong between 2000 and 2015. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 8, e116. https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2017.43 (2017).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G. & Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c332 (2010).

International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 329, 987–994. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199309303291402 (1993).

Social Welfare Department, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) Scheme. https://www.swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_socsecu/sub_comprehens/. (2020). Accessed on April 1, 2021.

Brusselaers, N. & Lagergren, J. The Charlson Comorbidity Index in registry-based research. Methods Inf. Med. 56, 401–406. https://doi.org/10.3414/me17-01-0051 (2017).

Armitage, J. N. & van der Meulen, J. H. Identifying co-morbidity in surgical patients using administrative data with the Royal College of Surgeons Charlson Score. Br. J. Surg. 97, 772–781. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6930 (2010).

Agresti, A. Foundations of Linear and Generalized Linear Models (Wiley, 2015).

Robins, J. M., Hernan, M. A. & Brumback, B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 11, 550–560 (2000).

Williamson, T. & Ravani, P. Marginal structural models in clinical research: When and how to use them?. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 32, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfw341 (2017).

Kawano, M. et al. Autocrine generation and requirement of BSF-2/IL-6 for human multiple myelomas. Nature 332, 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1038/332083a0 (1988).

Tao, L., Foran, J. M., Clarke, C. A., Gomez, S. L. & Keegan, T. H. Socioeconomic disparities in mortality after diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the modern treatment era. Blood 123, 3553–3562. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-07-517110 (2014).

Wang, M., Burau, K. D., Fang, S., Wang, H. & Du, X. L. Ethnic variations in diagnosis, treatment, socioeconomic status, and survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 113, 3231–3241. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23914 (2008).

Han, X. et al. Insurance status is related to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survival. Cancer 120, 1220–1227. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28549 (2014).

Smith, A. et al. Impact of age and socioeconomic status on treatment and survival from aggressive lymphoma: A UK population-based study of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 39, 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2015.08.015 (2015).

Frederiksen, B. L., Brown Pde, N., Dalton, S. O., Steding-Jessen, M. & Osler, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in prognostic markers of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Analysis of a national clinical database. Eur. J. Cancer (Oxford Engl. 1990) 47, 910–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.11.014 (2011).

Frederiksen, B. L., Dalton, S. O., Osler, M., Steding-Jessen, M. & de Nully Brown, P. Socioeconomic position, treatment, and survival of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Denmark—A nationwide study. Br. J. Cancer 106, 988–995. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.3 (2012).

Booth, C. M., Li, G., Zhang-Salomons, J. & Mackillop, W. J. The impact of socioeconomic status on stage of cancer at diagnosis and survival: A population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Cancer 116, 4160–4167. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25427 (2010).

Lee, B. et al. Effect of place of residence and treatment on survival outcomes in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. Oncologist 19, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0343 (2014).

Orsini, M., Trétarre, B., Daurès, J.-P. & Bessaoud, F. Individual socioeconomic status and breast cancer diagnostic stages: A French case–control study. Eur. J. Public Health 26, 445–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv233 (2016).

Pickett, K. E. & Pearl, M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: A critical review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 55, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.55.2.111 (2001).

Hussein, M., Diez Roux, A. V. & Field, R. I. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and primary health care: Usual points of access and temporal trends in a major US urban area. J. Urban Health 93, 1027–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0085-2 (2016).

Louwman, W. J. et al. A 50% higher prevalence of life-shortening chronic conditions among cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Br. J. Cancer 103, 1742–1748. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605949 (2010).

Lin, A.W.-C. & Wong, K.-H. Surveillance and response of hepatitis B virus in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 1988–2014. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. 7, 24–28. https://doi.org/10.5365/WPSAR.2015.6.3.003 (2016).

Liu, K. S. H. et al. A territorywide prevalence study on blood-borne and enteric viral hepatitis in Hong Kong. J. Infect. Dis. 219, 1924–1933. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz038 (2019).

Bo, W., Ghulam, M. & Kosh, A. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with hematologic disorders. Haematologica 104, 435–443. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.210252 (2019).

Yeo, W. et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 605–611. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.18.0182 (2009).

Legislative Council Panel on Health Services Update on Hospital Authority Drug Formulary. https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr08-09/english/panels/hs/papers/hs0608cb2-1740-4-e.pdf. Accessed on April 1, 2021.

Cronin, D. P. et al. Patterns of care in a population-based random sample of patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hematol. Oncol. 23, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.747 (2005).

Edwards, B. K. et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97, 1407–1427. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dji289 (2005).

Shah, B. K., Bista, A. & Shafii, B. Disparities in receipt of radiotherapy and survival by age, sex and ethnicity among patients with stage I diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 56, 983–986. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2014.940583 (2015).

Bista, A., Sharma, S. & Shah, B. K. Disparities in receipt of radiotherapy and survival by age, sex, and ethnicity among patient with stage I follicular lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 6, 101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2016.00101 (2016).

Olszewski, A. J., Shrestha, R. & Castillo, J. J. Treatment selection and outcomes in early-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma: Analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 625–633. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.58.7543 (2015).

Cronin-Fenton, D. P., Sharp, L., Deady, S. & Comber, H. Treatment and survival for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Influence of histological subtype, age, and other factors in a population-based study (1999–2001). Eur. J. Cancer 42, 2786–2793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.018 (2006).

Pal, S. K. & Hurria, A. Impact of age, sex, and comorbidity on cancer therapy and disease progression. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4086–4093. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2009.27.0579 (2010).

Yancik, R. et al. Report of the national institute on aging task force on comorbidity. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62, 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/62.3.275 (2007).

Lyman, G. H., Dale, D. C., Friedberg, J., Crawford, J. & Fisher, R. I. Incidence and predictors of low chemotherapy dose-intensity in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A nationwide study. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 4302–4311. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.03.213 (2004).

Yellen, S. B., Cella, D. F. & Leslie, W. T. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 86, 1766–1770. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/86.23.1766 (1994).

Glover, R. et al. Patterns of social support among lymphoma patients considering stem cell transplantation. Soc. Work Health Care 50, 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2011.595889 (2011).

Goldsbury, D. et al. Identifying incident colorectal and lung cancer cases in health service utilisation databases in Australia: A validation study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 17, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-017-0417-5 (2017).

Polubriaginof, F. C. G. et al. Challenges with quality of race and ethnicity data in observational databases. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 26, 730–736. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz113 (2019).

Bosch, X. et al. Time to diagnosis and associated costs of an outpatient vs inpatient setting in the diagnosis of lymphoma: A retrospective study of a large cohort of major lymphoma subtypes in Spain. BMC Cancer 18, 276. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4187-y (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr K.F. Tsang (Department of Clinical Oncology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong) for clerical support and data retrieval.

Funding

M.A.L.F. was supported by a Spanish National Health Institute Carlos III Miguel Servet-I Investigator grant/award (CP17/00206-EU-FEDER) and project grant (EU-FEDER-FIS PI-18/01593). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.F.L. and M.A.L.F. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. M.A.L.F. and A.K.N. are co-senior authors. Study conception and design: S.F.L. Acquisition of data: S.F.L. and M.A.L.F. Statistical analysis: S.F.L. and M.A.L.F. Interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: all authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Study supervision: M.A.L.F. and A.K.N.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.F., Evens, A.M., Ng, A.K. et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in treatment and relative survival among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a Hong Kong population-based study. Sci Rep 11, 17950 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97455-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97455-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.