Abstract

Power devices are operated under harsh conditions, such as high currents and voltages, and so degradation of these devices is an important issue. Our group previously found significant increases in reverse leakage current after applying continuous forward current stress to GaN p–n junctions. In the present study, we identified the type of threading dislocations that provide pathways for this reverse leakage current. GaN p–n diodes were grown by metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy on freestanding GaN(0001) substrates with threading dislocation densities of approximately 3 × 105 cm−2. These diodes exhibited a breakdown voltage on the order of 200 V and avalanche capability. The leakage current in some diodes in response to a reverse bias was found to rapidly increase with continuous forward current injection, and leakage sites were identified by optical emission microscopy. Closed-core threading screw dislocations (TSDs) were found at five emission spots based on cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy analyses using two-beam diffraction conditions. The Burgers vectors of these dislocations were identified as [0001] using large-angle convergent-beam electron diffraction. Thus, TSDs for which b = 1c are believed to provide current leakage paths in response to forward current stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vertical power devices based on gallium nitride (GaN) have recently been developed1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 as a means of minimizing power losses in electrical conversion systems requiring high current capabilities, such as automotive applications9,10. This technology is expected to make a significant contribution to future sustainable development initiatives. It is important for electrical systems, especially those used in automotive applications, to be reliable, and the reliability of vertical GaN p–n junctions subjected to high reverse biases, temperatures and current injections has been assessed. Because electric field crowding at device edges significantly lowers the breakdown voltage and can cause irreversible breakdown, various types of edge terminations have been developed and have demonstrated good avalanche capabilities7,8,11,12,13,14,15,16.

In power devices, the reverse leakage current below the breakdown voltage needs be controlled. The previous studies discussed the impacts of the threading dislocations as sources of reverse leakage current, focusing on the initial reverse bias characteristics17,18,19,20,21. Compared with the number of studies regarding the initial reliability of these devices, there have been few reports concerning hold tests under high reverse bias or high current stress22,23,24. Kizilyalli et al.22 subjected p–n diodes on freestanding GaN substrates having threading dislocation densities in the range of 104 to 106 cm−2 to high temperatures and reverse biases and found that the majority of the diodes exhibited a durability of over 1000 h. Our group also demonstrated that GaN p–n junctions with threading dislocation densities less than 104 cm−2 were not degraded even under a high reverse bias corresponding to the avalanche condition at 175 °C over time spans of up to 1 h24. However, in contrast to this highly robust behavior, the reverse leakage current in some diodes rapidly increased after continuous forward current stress was applied22,23,24. This degradation mode could be a significant issue in metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors because, in such devices, a power circuit turns on the body p–n diode to allow a reflux current to flow during the switching operation. In a previous study, we found the degradation induced by a forward current occurred locally and might originate from threading dislocations24, although the specific defects in the current leakage path were not determined. Identifying these defects is very important for the further improvement of GaN bulk substrates because, while the elimination of all defects would be extremely difficult, the reduction of one type of defect may be feasible.

In the present work, we performed cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses of threading dislocations extracted from current leakage paths induced by forward current stress. We also identified the Burgers vector of the dislocations most frequently found at the leakage paths, using the large-angle convergent-beam electron diffraction (LACBED) method25,26.

Methods

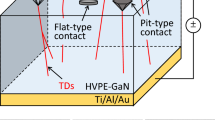

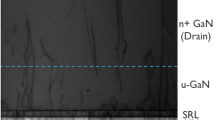

The layered structures of the experimental p–n junctions were grown using metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy in conjunction with commercially available freestanding GaN(0001) substrates prepared via hydride vapor phase epitaxy. The typical threading dislocation density in these specimens was 3 × 105 cm−2 based on the etch pit density using the fused alkali. As shown in Fig. 1, the layered structure was composed of (from top to bottom) a 0.1 μm-thick p+-type GaN contact layer doped with magnesium (Mg) at a concentration of 5 × 1019 cm−3, a 1.5 μm-thick p-type GaN layer doped with Mg at a concentration of 7.7 × 1017 cm−3, a 1.5 μm-thick n-type GaN layer doped with silicon (Si) at a concentration of 3.1 × 1017 cm−3 and an n+-type GaN buffer layer with a Si concentration of 1.8 × 1018 cm−3. The surface electric field was reduced by forming a bevel mesa through the p-type layer at an angle of 6.2° to 7.2° by inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching12,27. A nickel/gold (Ni/Au) metal stack was deposited as an anode electrode and was subsequently sintered at 500 °C under oxygen to form the Ohmic contact. Finally, a titanium/aluminum/Ni (Ti/Al/Ni) cathode electrode was formed on the reverse side of the substrate. In the present study, we focus on the characterization of three representative diodes with different diameters. Specifically, the anode and junction diameters (Φanode and Φpn) were 60 and 184 μm for diode #1AX, 220 and 342 μm for #1CX, and 320 and 442 μm for #1DX.

The electrical properties of the specimens were sequentially characterized. Reverse bias sweeps up to the breakdown voltage were conducted at 25, 100 and 175 °C, followed by 1 h hold tests at 80% of the breakdown voltage at these respective temperatures. Hold tests performed for a duration of 1 h at a constant current of 1 mA, which corresponded to the avalanche condition, were subsequently carried out at the same temperatures. Following this, continuous forward current stress was applied by increasing the current density in a stepwise manner. The current density, J, during these stress trials was 50, 100, 200 and 500 A/cm2 (normalized by the anode area) and was each applied for 1 h. Those diodes that had exhibited increased reverse leakage current during the forward current tests were observed by emission microscopy (EMS) using an InGaAs detector sensitive over the wavelength range of 900 to 1600 nm. Defect-related carrier recombination sites associated with local leakage paths appeared as luminous points in the resulting EMS images28. It should be noted that these EMS observations were performed from the backside of the device after removing the cathode electrode by polishing. TEM specimens having (\(1\overline{1}00\)) cross-sections were fabricated near the luminous points and 0002 and \(11\overline{2}0\) two-beam diffractions were assessed. The LACBED analyses were performed using a JEOL JEM-ARM300F at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. This technique allowed the determination of the Burger vectors associated with dislocations based on analyzing the interactions between high-order Laue zone lines and a threading dislocation line25,26.

Results and discussion

Figure 2 presents the current density–voltage (J–V) curves acquired in conjunction with reverse biases at 25, 100 and 175 °C for three representative diodes. Note that these J data have been normalized by the junction areas. The breakdown voltages at 25 °C were in the range of 191–192 V, and so were close to the ideal avalanche breakdown voltage of 174 V expected from the doping concentration in these devices29,30. The breakdown voltages were found to increase with increasing temperature, which is characteristic of avalanche breakdown12,27. All diodes exhibited repeatable breakdown characteristics, indicating good avalanche capabilities owing to the shallow beveled mesa termination12,27. The leakage currents and avalanche voltages for all diodes were stable throughout each 1 h hold test both at 80% of the breakdown voltage and under avalanche conditions at 25, 100 and 175 °C (see Supplementary Information). These results were in keeping with those of a previous study24 using p–n diodes fabricated on freestanding GaN substrates having threading dislocation densities less than 104 cm−2. It is therefore evident that threading dislocations had a minimal effect on the robustness of such devices when subjected to reverse bias stress.

Figure 3 shows the forward and reverse bias characteristics of the specimens during continuous forward current trials. Diode #1AX, which had the smallest anode diameter (Φanode = 60 μm), showed constant forward and reverse bias properties during the test period. We also confirmed that the other two diodes (with Φanode = 60 and 120 μm) were similarly stable (data not shown). In contrast, the leakage current levels observed in the case of diodes #1CX and #1DX (with respective Φanode values of 220 and 320 μm) rapidly increased with increasing J stress. Similar degradation was demonstrated by the other three diodes with Φanode values of more than 220 μm (data not shown). Figure 4a and b provide EMS images for diodes #1CX and #1DX acquired after continuous J stress tests at reverse biases of − 120 and − 78 V, respectively. Since the EMS observations were performed from the backside of each device, these images have been flipped horizontally so as to present the views from the anode side. Two luminous points, A and B, are apparent in the image of diode #1CX, while three EMS points, C, D and E, can be seen in that of diode #1DX. Based on the average threading dislocation density of 3 × 105 cm−2, 110 and 240 threading dislocations would be expected to be present under the anode electrodes in samples #1CX and #1DX, whereas only two and three luminous points are apparent in the EMS images, respectively. In addition, the diodes with Φanode = 60 and 120 μm that showed no degradation would be expected to contain 8.5 and 34 threading dislocations under the anode electrodes, respectively. These results suggest that only a few threading dislocations provided reverse current leakage paths during the continuous J tests, while the reverse leakage current at the majority remained at the low level as before experiencing the forward current stress.

(a)–(c) Forward and (d)–(f) reverse current density–voltage curves acquired during continuous current injection tests. The injected current density values have been normalized by the anode areas in (a)–(c), and anode diameters, Φanode, are provided at the top of each figure. The reverse leakage current density values in (d)–(f) have been normalized by the area of the p–n junction, and the junction diameters, Φpn, are provided at the base of each figure.

(a) (b) EMS images of diodes #1CX and #1DX. The inserted images are magnifications of areas near the respective luminous points. In the case of diode #1CX shown in (a), two luminous points, A and B, were observed in conjunction with a reverse leakage current of 500 nA at –120 V. For diode #1DX shown in (b), three luminous points, C, D and E, appeared at a reverse leakage current of 400 nA at –78 V.

Figure 5 shows dark-field cross-sectional TEM images acquired at luminous points A and C. The g = 0002 and g = \(11\overline{2}0\) diffraction conditions allowed the visualization of threading dislocations having screw and edge components, respectively. In the case of luminous point A, one threading dislocation visible only for the 0002 diffraction condition was detected and was assigned to a closed-core threading screw dislocation (TSD). For luminous point C, one closed-core TSD along with a threading edge dislocation (TED) was observed. Both threading dislocations at point C passed through the p–n junction, although they disappeared near the junction as a consequence of the thinning process applied to the TEM specimen. A TSD passing through the junction was found at each of EMS points B, D and E in the degraded diodes #1CX and #1DX, as summarized in Table 1. We also performed a TEM analysis for the EMS point previously examined24 in degraded p-n diodes on an acidic ammonothermal-grown freestanding GaN substrate having a threading dislocation density of less than 104 cm−2 and found a TSD (data not shown). As summarized in Table 1, we detected the common TSDs at eleven EMS points for p–n diodes on two different types of GaN substrates. These results suggest that closed-core TSDs provided leakage pathways after the application of forward current stress. In the p–n diodes of the present study, the portion of TSDs to the total threading dislocations is unknown because it is not easy to separate TSDs from the threading mixed dislocations (TMDs) even using the etch pit methods31. In general, the ratio of the number of TSDs to the total number of threading dislocations in freestanding GaN substrates will be relatively small31,32,33. This may explain the robust nature of some p-n diodes incorporating threading dislocations and the small number of luminous points compared with the total number of threading dislocations seen in the EMS images after continuous J stress.

LACBED analyses were performed to identify the Burgers vectors, and Fig. 6a and b show the two-beam bright-field TEM images obtained from luminous point D, which indicate the existence of one TSD. The Burgers vector for this TSD can be expressed as b = [000x], and Fig. 6c and d present LACBED images for this dislocation. It should be noted that for higher order diffractions g can interact with a threading dislocation line, to split into multiple lines whose number is \(n = {\varvec{g}}\cdot {\varvec{b}}\) 25,26. Figure 6d shows the magnified LACBED pattern near g = 0008 and exhibits eight split lines (n = 8). We were therefore able to determine the Burgers vector for the TSD associated with point D as b = [0001]. The same analysis was performed for the TSD at emission point A and for the TSD at emission points Y and Z in the previously examined diode on the acidic ammonothermal-grown GaN substrate having the threading dislocation density less than 104 cm−2, and the identical conclusions of b = [0001] were obtained. These results suggest that simple TSDs having b = 1c provided leakage paths after the continuous J stress tests although we cannot say all TSDs with b = 1c being the leakage pathways due to the small number of LACBED examinations at the present. In previous work using p–n diodes with much lower threading dislocation densities, there was good agreement between EMS points acting as leakage paths and the threading dislocations in the topographic images before the stress test24. This indicates TSDs were not mobile during the J stress test. Furthermore, other types of threading dislocations were not observed near the leakage spots in Ref.24. Therefore, we propose that interactions between threading dislocations involving motion during the J stress tests were unlikely. Nakano et al.34 theoretically suggested that complexes formed from Mg atoms and TSDs can act as current leakage paths in p-type GaN. In the case that current injection promotes Mg diffusion along TSDs, Nakano’s suggestion could explain the present degradation mode, although further work is required to identify the conduction mechanism at the TSDs.

Bright-field TEM images of the TSD at EMS point D in diode #1DX with (a) g = 0002 and (b) g = \(11\overline{2}0\). Note that the sample surface was directed downward. (c) Dark-field LACBED image of the TSD (denoted by the red dashed line). (d) Magnified LACBED pattern around g = 0008. The white arrows indicate eight split lines resulting from the interaction of the Laue zone line for g = 0008 and the TSD line.

Conclusions

Threading dislocations thought to act as current leakage paths after continuous forward current tests in GaN p–n junctions were extracted and characterized. Trials with p–n diodes fabricated on freestanding GaN substrates with threading dislocation densities of approximately 3 × 105 cm−2 showed that the leakage current was increased for devices with Φanode values of more than 220 μm during forward current injection, whereas diodes having a Φanode of 60 μm were generally stable. EMS observations from the backside of each device identified the current leakage paths and the same closed-core TSDs were identified near each luminous point in these images. The Burgers vector of the extracted TSDs was identified as b = [0001]. The results of this work suggest that simple TSDs at least with b = 1c provided significant leakage pathways in response to excitation during the continuous forward current stress trials.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nie, H., Diduck, Q., Alvarez, B., Edwards, A. P., Kayes, B. M., Zhang, M., Ye, G., Prunty, T., Bour, D. & Kizilyalli, I. C. 1.5-kV and 2.2-mΩ-cm2 Vertical GaN Transistors on Bulk-GaN Substrates. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 35, 939 (2014).

Oka, T., Ina, T., Ueno, Y. & Nishii. J. 1.8 mΩ·cm2 vertical GaN-based trench metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors on a free-standing GaN substrate for 1.2-kV-class operation. Appl. Phys. Exp. 8, 054101 (2015).

Shibata, D., Kajitani, R., Ogawa, M., Tanaka, K., Tamura, S., Hatsuda, T., Ishida, M. & Ueda, T. 1.7 kV / 1.0 mΩcm2 normally-off vertical GaN transistor on GaN substrate with regrown p-GaN/AlGaN/GaN semipolar gate structure. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEEE, San Francisco, 2016), p. 248.

Zhang, Y., Sun, M., Piedra, D., Hu, J., Liu, Z., Lin, Y., Gao, X., Shepard, K. & Palacios T. 1200 V GaN vertical fin power field-effect transistors. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEEE, San Francisco, 2017), p. 215.

Oka, T. Recent development of vertical GaN power devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 58, SB0805 (2019).

Tanaka, R., Takashima, S., Ueno, K., Matsuyama, H. & Edo, M. Demonstration of 1200 V/1.4 mΩcm2 vertical GaN planar MOSFET fabricated by an all ion implantation process. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., 59, SGGD02 (2020).

Liu, J., Xiao, M., Zhang, Y., Pidaparthi, S., Cui, H., Edwards, A., Baubutr, L., Meier, W., Coles, C. & Drowley, C. 1.2 kV vertical GaN Fin JFETs with robust avalanche and fast switching capabilities. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEEE, Virtual, 2020), p. 477.

Liu, J., Xiao, M., Zhang, R., Pidaparthi, S., Cui, H., Edwards, A., Craven, M., Baubutr, L., Drowley, C. & Zhang., Y. 1.2-kV vertical GaN Fin-JFETs: high-temperature characteristics and avalanche capability. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 68, 2025 (2021).

Kachi, T. Recent progress of GaN power devices for automotive applications. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 53, 100210 (2014).

Kachi, T. GaN devices for automotive application and their challenges in adoption. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEEE, San Francisco, 2018), p. 452.

Kizilyalli, I. C., Edwards, A. P., Nie, H., Disney, D. & Bour, D. High voltage vertical GaN p-n diodes with avalanche capability. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 60, 3067 (2013).

Maeda, T. et al. Design and fabrication of GaN p-n junction diodes with negative Beveled-Mesa termination. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 40, 941 (2019).

Fukushima, H., Usami, S., Ogura, M., Ando, Y., Tanaka, A., Deki, M., Kushimoto, M., Nitta, S., Honda, Y. & Amano, H. Vertical GaN p–n diode with deeply etched mesa and the capability of avalanche breakdown. Appl. Phys. Exp. 12, 026502 (2019).

Ji, D., Li, S., Ercan, B., Ren, C. & Chowdhury, S. Design and fabrication of ion-implanted moat etch termination resulting in 0.7 mΩ·cm2/1500 V GaN diodes. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 41, 264 (2020).

Ohta, H. et al. Two-step mesa structure GaN p-n diodes with low on-resistance, high breakdown voltage, and excellent avalanche capabilities. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 41, 123 (2020).

Matys, M., Ishida, T., Nam, K. P., Sakurai, H., Kataoka, K., Narita, T., Uesugi, T., Bockowski, M., Nishimura, T., Suda, J. & Kachi, T. Design and demonstration of nearly-ideal edge termination for GaN p–n junction using Mg-implanted field limiting rings. Appl. Phys. Exp. 14, 074002 (2021).

Kachi, T. & Uesugi, T. Evaluation of GaN substrate for vertical GaN power device applications. Sensors Mater. 25, 219 (2013).

Usami, S., Ando, Y., Tanaka, A., Kentaro Nagamatsu, K., Deki, M., Kushimoto, M., Nitta, S., Honda, Y., Amano, H., Sugawara, Y., Yong-Zhao Yao, Y.-Z. & Ishikawa, Y. Correlation between dislocations and leakage current of p-n diodes on a freestanding GaN substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 182106 (2018).

Usami, S., Tanaka, A., Fukushima, H., Ando, Y., Deki, M., Nitta, S., Honda, Y., & Amano, H. Correlation between nanopipes formed from screw dislocations during homoepitaxial growth by metal-organic vapor-phase epitaxy and reverse leakage current in vertical p–n diodes on a free-standing GaN substrates. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 58, SCCB24 (2019).

Usami, S., Mayama, N., Toda, K., Tanaka, A., Deki, M., Nitta, S., Honda, Y., & Amano, H. Direct evidence of Mg diffusion through threading mixed dislocations in GaN p–n diodes and its effect on reverse leakage current. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 232105 (2019).

Kanechika, M., Yamaguchi, S., Imanishi, M. & Mori, Y. Evaluation of dislocations under the electrodes of GaN pn diodes by X-ray topography. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 58, SCCD22 (2019).

Kizilyalli, I. C., Bui-Quanga, P., Disney, D., Bhatia, H. & Aktas, O. Reliability studies of vertical GaN devices based on bulk GaN substrates. Microelectron. Reliab. 55, 1654 (2015).

Fabris, E. et al. Degradation of GaN-on-GaN vertical diodes submitted to high current stress. Microelectron. Reliab. 88–90, 568 (2018).

Narita, T. Nagasato, Y., Kanechika, M., Kondo T., Uesugi, T., Tomita, K., Ikeda, S., Yamaguchi, S., Kimoto, Y., Kosaki, M., Oka T., Kojima, J. & Suda, J. Increase of reverse leakage current at homoepitaxial GaN p-n junctions induced by continuous forward current stress. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 253501 (2021).

Chernsa, D. & Morniroli, J.-P. Analysis of partial and stair-rod dislocations by large angle convergent beam electron diffraction. Ultramicroscopy 53, 167 (1994).

Kokubo, N., Tsunooka, Y., Fujie, F., Ohara, J., Onda, S., Yamada, H., Shimizu, M., Harada, S., Tagawa, M. & Ujihara, T. Determination of edge-component Burgers vector of threading dislocations in GaN crystal by using Raman mapping. Appl. Phys. Exp. 11, 111001 (2018).

Maeda, T., Narita, T., Ueda, H., Kanechika, M., Uesugi, T., Kachi, T., Kimoto, T., Horita, M. & Suda, J. Parallel-plane breakdown fields of 2.8–3.5 MV/cm in GaN-on-GaN p-n junction diodes with double-side-depleted shallow bevel termination. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEEE, San Francisco, 2018), p. 687.

Meneghini, M., Trivellin, N., Pavesi, M., Manfredi, M., Zehnder, U., Hahn, B., Meneghesso, G. & Zanoni, E. Leakage current and reverse-bias luminescence in InGaN-based light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 173507 (2009).

Maeda, T., Narita, T., Yamada, S., Kachi, T., Kimoto, T., Horita, M. & Suda, J. Impact ionization coefficients in GaN measured by above- and sub-Eg illuminations for p−/n+ junction. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEEE, San Francisco, 2019), p. 70.

Maeda, T., Narita, T., Yamada, S., Kachi, T., Kimoto, T., Horita, M. & Suda, J. Impact ionization coefficients and critical electric field in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 185702 (2021).

M. Albrecht, M., Weyher, J. L., Lucznik, B., Grzegory, I., and Porowski, S. Nonradiative recombination at threading dislocations in n-type GaN: Studied by cathodoluminescence and defect selective etching, Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 231909 (2008).

Sintonen, S., Suihkonen, S., Jussila, H., Danilewsky, A., Stankiewicz, R., Tuomi, T. O, and Lipsanen, H. Large-area analysis of dislocations in ammonothermal GaN by synchrotron radiation X-ray topography. Appl. Phys. Exp. 7, 091003 (2014).

Yao, Y. et al. Correlation between structural properties and nonradiative recombination behaviors of threading dislocations in freestanding GaN substrates grown by hydride vapor phase epitaxy. CrystEngComm 48, 8277 (2020).

Nakano, T., Harashima, Y., Chokawa, K., Shiraishi, K., Oshiyama, A., Kangawa, Y., Usami, S., Mayama, N., Toda, K., Tanaka, A., Honda, Y. & Amano, H. Screw dislocation that converts p-type GaN to n-type: Microscopic study on Mg condensation and leakage current in p–n diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 012105 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Center for Integrated Research of Future Electronics, Transformative Electronics Facilities (C-TEFs) at Nagoya University for fabricating the devices used in this work. The synchrotron radiation X-ray topography analyses were performed at the BL16B2 (Proposal Nos. 2018B5370, 2019A5370, 2019B5370 and 2020A5370) and BL20B2 (Proposal Nos. 2019B1042 and 2020A1039) beamlines at the SPring-8 facility with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. Narita planned the series of experiments and wrote the manuscript. M. Kanechika evaluated the electrical properties of the samples. J. Kojima and H. Watanabe performed the TEM and LACBED analyses. T. Kondo and T. Uesugi fabricated p-n diodes with a beveled mesa structure. S. Yamaguchi and Y. Kimoto contributed to the synchrotron X-ray topography experiments along with M. Kanechika. Although the X-ray topographic image did not appear in this paper, the results were utilized to select the test diodes. K. Tomita performed the MOVPE growth of the experimental samples along with T. Narita. Y. Nagasato and S. Ikeda designed the test element group pattern for the diodes and performed the initial characterizations of the diodes. M. Kosaki and T. Oka contributed to the identification of defects using emission microscopy. J. Suda led the research team. All authors discussed the contents of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Narita, T., Kanechika, M., Kojima, J. et al. Identification of type of threading dislocation causing reverse leakage in GaN p–n junctions after continuous forward current stress. Sci Rep 12, 1458 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05416-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05416-3

This article is cited by

-

Characterization of dislocations induced by Vickers indentation in GaN for explaining size ratios of dislocation patterns

Journal of Materials Science (2024)

-

Development and analysis of thick GaN drift layers on 200 mm CTE-matched substrate for vertical device processing

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Characterization of dislocations at the emission site by emission microscopy in GaN p–n diodes

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Impact of Substrate Morphology and Structural Defects in Freestanding Gallium Nitride on the Breakdown Characteristics of GaN-on-GaN Vertical Diodes

Journal of Electronic Materials (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.