Abstract

With rapid expansion of offshore renewables, a broader perspective on their ecological implications is timely to predict marine predator responses to environmental change. Strong currents interacting with man-made structures can generate complex three-dimensional wakes that can make prey more accessible. Whether localised wakes from man-made structures can generate predictable foraging hotspots for top predators is unknown. Here we address this question by quantifying the relative use of an anthropogenically-generated wake by surface foraging seabirds, verified using drone transects and hydroacoustics. We show that the wake of a tidal energy structure promotes a localised and persistent foraging hotspot, with seabird numbers greatly exceeding those at adjacent natural wake features. The wake mixes material throughout the water column, potentially acting like a prey conveyer belt. Our findings highlight the importance of identifying the physical scales and mechanisms underlying predator hotspot formation when assessing the ecological consequences of installing or removing anthropogenic structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an era of intense marine urbanisation1, understanding scale-dependent physical forcing can help predict how marine predators may respond to environmental change. Predators rely on a multitude of physical processes, which dynamically influence foraging behaviour2,3 and success4. In the open ocean, predator foraging has been associated with mesoscale (10−100 km) physical features, such as fronts and eddies5,6,7. However, even fine- ( < 1 km, e.g., internal waves3) or local- (10−100 m, e.g., island wakes8) scale physical features may create small-scale predator hotspots9,10. The importance of these fine and local-scale physical processes is heightened in seabirds restricted to shallow plunge diving techniques, such as gulls and terns, where prey availability near the sea surface governs foraging site selection11,12,13. Consequently, tern species (Sternidae) tend to focus their foraging activity in areas of bathymetry-generated turbulence or shallow upwellings that consistently make prey available near the surface11,12,14,15. Such physically enhanced prey availability and its predictability seem to determine seabird foraging habitat rather than prey density alone12,16,17,18,19,20. Therefore, the identification of local flow processes interacting with bathymetric features (natural or man-made) can improve our understanding of the physical mechanisms promoting foraging hotspot formation and persistence in dynamic coastal systems21.

The periodic emergence of tidally driven bathymetry-induced turbulence, shallow upwellings or more ephemeral turbulent structures such as boils—circular regions of local upwelling22—are characteristic of strongly tidal seas. The introduction of anthropogenic structures into such dynamic environments adds further complexity to local flow processes, potentially triggering ecological implications23. Man-made structures modify local hydrodynamics24, including flow velocities25 and wake effects26,27,28. Further, a von Kármán vortex street29, characterised by distinct and repeatable eddy trajectories, may occur in the wake of embedded structures when placed in strong, near-laminar flows30. While fish may exploit the lee of a structure as a flow refuge31 or use small-scale vortices (e.g., < 1:1 ratio of vortex to fish size) to Kármán gait32, an extreme downstream wake with eddy vortices of sufficient size and vorticity33 can vertically displace or overturn fish in fast, unsteady flows31,34,35,36, potentially making them accessible to surface-foraging predators.

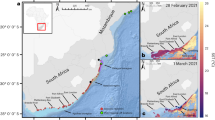

We hypothesised that a vortex street attributable to a man-made structure could present an as yet unexplored mechanism for localised predator hotspot formation. Here, we investigate whether a localised ( < 1 km) anthropogenically generated wake can present a reliable foraging location for surface-feeding seabirds (Sternidae), comparable to those at adjacent natural wake features. SeaGen, the world’s first grid-connected tidal energy turbine, currently being decommissioned, produces a wake with vortex shedding approaching a von Kármán vortex street30. The device consisted of a monopile structure (3 m diameter) attached to a quadropod foundation fixed on the seabed (water depth about 25 m) with a 27 m long crossbeam supporting the original rotors on either side of the tower 15 m above the seabed. During this study, the rotors had already been removed, however, the monopile itself contributes considerably to the vortex shedding in the downstream wake as shown through large eddy simulations30. SeaGen is situated in a dynamic tidal channel (‘‘the Narrows’’) in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland, in proximity to colonies of summer-breeding tern species (Sterna hirundo, S. sandvicensis, S. paradisaea). The channel also provides diverse foraging opportunities with natural wake features commonly used by terns, therefore presenting a suitable study system. Two neighbouring extreme natural wake features, an island (Walter’s Rock) and a whirlpool structure (Routen Wheel), within the channel were selected to compare the terns’ use of the natural wakes with the man-made wake (Fig. 1). Our findings show that among all three wake features investigated, the flood wake associated with the man-made structure promotes the most persistent and intense foraging aggregations of terns. We further provide evidence that foraging over the wake is highly localised, highlighting the importance and ecological implications of localised physical forcing around man-made structures.

Location of wake features in the Narrows tidal channel situated in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland, UK. a Overview map showing the study area within the Narrows, highlighted by a red box. b Location of wake features in the Narrows. c–e Insets showing the turbulent structures associated with each wake feature. Note: particle release site indicates the release of passive particles (as a proxy for prey organisms) from the Irish Sea during flood tide within a hydrodynamic model. OSNI data was reproduced from Land and Property Services data with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown copyright and database rights MOU203. Bathymetry: © Crown Copyright/SeaZone Solutions. All Rights Reserved. Licence No. 052006.001 31st July 2011. Not to be Used for Navigation

Results

Tern foraging patterns vary among wake features

The number of terns foraging at each wake feature was assessed using vantage point surveys (July–August 2018) with observations covering different tidal states (ebb versus flood, spring versus neap), recording variations in tern abundance across hydrodynamic conditions. The occurrence of conspicuous topographic and anthropogenic landmarks allowed the construction of plots with approximately the same area, with calculations based on bearings and distances from the vantage point. For SeaGen, observations were spatially divided into North (area of flood tide wake) and South (area of ebb tide wake) of the foundation, respectively. While the physical structure of SeaGen’s wake does not differ between the flood and ebb tide, the spatial separation was needed to ensure equal spatial extent per site. Further, it helped to assess whether terns were solely attracted to the environmental cue of turbulence (ecological trap37) or if aggregations were coupled to the ebb-flood tidal cycle.

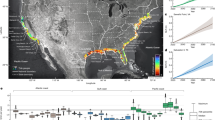

Tidal coupling was evident with the highest probability of encountering terns at SeaGen North and Walter’s Rock during flood tides, and Routen Wheel during ebb tides (Fig. 2a, b). The largest flocks of terns were encountered at SeaGen North during peak flood tides (Fig. 2c), with aggregations frequently exceeding 50 birds (Fig. 2a). On average, tern numbers observed foraging at the SeaGen North site during peak flood were three times as many as those foraging at either of the two natural wake sites (Fig. 2c). Because of high overdispersion and zero-inflation in the datasets, a hurdle-model was used to divide statistical analysis into presence-absence and count components38. In summary, the mean probability of encountering terns and number of terns if encountered per minute differed significantly among the wake features (Table 1). There were significant variations in probabilities of encountering terns and numbers of terns if encountered (Fig. 2a, b) across tidal states at most locations (an exception to this was SeaGen South).

Tern counts over tidal state at each wake feature. a, b Mean ± SE variations in the predicted probability of encountering terns and the number of terns if encountered per minute across tidal states around SeaGen North and South (a), the Routen Wheel and Walter’s Rock (b) wake features, respectively. Crosses indicate the recorded number of terns if encountered binned into periods representing eight different states (1 h 20 min) of the ebb-flood cycle. HT = high tide, LT = low tide. c Mean ± SE variations in the predicted probability of encountering terns and the number of terns if encountered per minute across tidal states and locations. Tidal states represent peak current speeds in ebb and flood directions. All predictions (a–c) were made using model parameters from a general-additive mixed effect model (GAMM) with significance in both probabilities and numbers across tidal states shown in Table 1

Tern foraging in relation to man-made wake

Overall, the probability and size of tern aggregations was highest at the man-made structure (SeaGen North), triggering a fine-scale investigation of its wake dynamics. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) transects above SeaGen over several tidal cycles visualised the dynamic vortex shedding of the wake and the exact spatial extent of tern foraging, thereby overcoming the oblique angle of the vantage point observer. Consistent with the vantage point surveys, these transects recorded that terns focused their foraging activity almost exclusively over the flood wake (SeaGen North; Fig. 3a). The lee wake vortices showed the distinct and predictable pattern consistent with a von Kármán vortex street, with a surface-tracked eddy shedding frequency of 10–14 min−1.

Tern distribution during peak flood tide in relation to SeaGen’s wake structure. a Georeferenced composite panoramic image from unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) transect survey with terns identified (yellow circles—one enlarged for clarity). The orientation of the x-axis is 349 degrees. Magenta and yellow boxes indicate tracking regions shown in Fig. 4. b, c Horizontal velocity magnitude (ms−1) profile from the southern (cyan) and northern (green) ADCP transect, respectively. d, e Maximum acoustic backscatter (dB re 1 m−1) profile from the southern and northern ADCP transect, respectively. The North transects show a clear water column velocity deficit (c) and backscatter (an indicator for macro-turbulence) signature (e) in the area of the flood wake (Y = −20 to 20 m)

To assess vertical wake effects throughout the water column, vessel-mounted acoustic doppler current profiler (ADCP) transects were run either side of the SeaGen foundation throughout a flood-ebb tidal cycle. The upstream near-laminar flow exceeding 5 ms−1 experiences a clear velocity deficit downstream in the midline of the structure throughout the water column with a cross-stream extent of 45 m at ~100 m downstream of SeaGen (Fig. 3b, c). The corresponding signature of elevated acoustic backscatter, an indicator for macro-turbulence39, visible in the downstream wake (Fig. 3e—compared to the upstream flow, Fig. 3d) is most likely dominated by entrained bubbles40, and to a lesser extent, sediment re-suspension41 and perhaps fish42,43. Bounded by the sea surface and seafloor, the backscatter signature from the wake of the structure is distinct from adjacent water. This provides evidence that the turbulent eddies within the flow are powerful enough to up-and down-well submerged material throughout the entire water column. While extreme water column scattering from bubbles and sediment precludes the acoustic extraction of fish targets from turbulence, the wake likely has the potential to act as a prey “conveyor belt” for surface foragers.

Applying machine learning algorithms to distinguish terns from other moving targets (e.g., foam), flight trajectories recorded over the wake region (Fig. 4a) showed a high degree of in-flight sinuosity, typical for area-restricted search behaviour in response to increased prey intake rate/profitability (characterised by decreased flight speeds and frequent turning2, Fig. 4b). The terns forage almost exclusively over the vortex street with mostly transit flights to and from the colony outside of this central region.

Tern flight trajectories recorded during peak flood tide in relation to SeaGen’s wake structure. a Georeferenced trajectories overlaid on time-average video images showing brighter region of foam/suspended material in wake. All trajectories of over 2 s duration are shown from recording periods of 140 s (red, 136 in total) and 125 s (magenta, 196 in total). b Sequence of images of an individual tern as it follows the trajectory indicated in blue in a (dot indicates start). Only every fourth image (0.16 s time interval) is shown for clarity in row-wise order starting at the top-left of the panel

Particle flux corresponds with tern foraging patterns

Finally, the persistent use of the SeaGen (North) wake by the terns limited to the flood tidal cycle was explored using a hydrodynamic model coupled to an ecological module. Passive particles as a proxy for small prey organisms were released from the Irish Sea, outside the entrance of the Lough at the beginning of a flood tide (Fig. 1b). The flux of incoming potential prey items to SeaGen’s flood wake originates 70 min upstream from outside the Lough, corresponding with the rise in tern sightings ~60 min post low water slack.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to link indirect physical interactions (a downstream wake) of a renewable energy structure with top predators, highlighting the hitherto overlooked ecological implications of localised physical forcing around man-made structures. While top predator use of anthropogenic structures has been observed elsewhere44,45, distinct mechanisms may be in place to explain such associations. Namely, (1) natural reefing can increase fish biomass46, (2) fish can seek flow refuge in the immediate lee of a structure34 and (3) downstream wake effects can make incoming prey available near the surface through displacement35,47. The latter mechanism is currently the least explored in a natural setting despite its importance in high-flow environments, highlighting the relevance of our findings. While natural bathymetric features and associated patterns of shear lines and wake effects have been shown to attract top predators8, the man-made wake in this study promoted the most persistent and intense foraging aggregations of terns among all wake features investigated. While we did not assess prey vertical distribution, turbulent vertical velocity fluctuations within the wake were greater than 0.5 ms−1 (Supplementary Fig. 1), exceeding swimming performance of typical piscivorous tern prey items13 (e.g., sandeel48 in the order of 0.2 ms−1 or sprat/herring49 in the order of 0.4 ms−1) and may have the potential to displace prey. Therefore, our future studies will focus on assessing prey distribution and availability within both the inflows and wakes under different tidal states.

With the intensification of man-made structures in coastal seas, new synergies between these and marine predators are likely. Our findings demonstrate that wake features, predictable in time and space, persistently attract top predators at highly localised scales. We also provide the first empirical evidence that localised hydrodynamic forcing attributable to an anthropogenic structure can present a mechanism to promote a foraging hotspot, where predator aggregations exceed those at adjacent natural wake features. A broader perspective on the ecological implications of offshore installations is critical23 and requires the identification of such localised physical processes underlying top predator hotspot formation. For seabirds, there is concern that the introduction of renewable energy devices could lead to avoidance, thereby negatively impacting on energy expenditure50. Likewise, it has been suggested that hydrodynamic forces around hard structures could modify prey availability, thereby increasing a seabird’s rate of energy acquisition51. While our findings suggest that terns exploit the flood wake of a device, an overall ecological (population-level) benefit through increased individual energy acquisition can only be determined when accounting for parameters relating to, e.g., foraging success, prey profitability, and breeding performance51,52.

In the expanding renewable energy sector (e.g., > 4000 offshore wind turbines in Europe53), monopile foundations similar to the SeaGen design present the most common substructure (66%53) and lead to comparable wake vortices25,27,54. However, even submerged tidal turbines, and more so arrays, placed in unsteady flows will change the local hydrodynamic regime, including wake effects26,55 and more empirical data are required to predict changes in hydrodynamics and foraging habitat.

With SeaGen being decommissioned, its removal will undoubtedly change the foraging aggregations observed here. The decommissioning process, often requiring the complete removal of an aging structure56, is currently being re-considered globally by evidence of potential ecological benefits through artificial reef effects57 and increased fish biomass46,58 if parts remain in the sea. However, there is equal concern about the possible ecological impacts of artificial structures on marine vertebrates59 and in terms of their benthic footprint60,61. Renewable energy installations show some ecological synergies to oil-and gas platforms44,60,62 and could become an important contributor to the foreseen ʻdecommissioning crisis63ʼ if not addressed in a timely manner. Therefore, when designing the decommissioning removal scope of devices, a case-by-case determination of the ecological benefits or disadvantages of seemingly obsolete installations is required64.

Methods

Study site

All wake features investigated are situated in the Narrows, a tidal channel linking Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland, UK, with the Irish Sea (Fig. 1). The three sites investigated were (1) Walter’s Rock (54° 22.992’N, 5° 33.504’W), an island located on the periphery of the main channel, generating local upwelling and shear lines extending both into the channel and the near-shore shallows; (2) SeaGen (54° 22.122’N, 5° 32.766’W), located in the mid-channel experiencing the highest current magnitudes39 and (3) the Routen Wheel (54° 21.698’N, 5° 32.476’W), turbulent whirlpool structures that are generated from a shallow pinnacle (5 m depth) surrounded by 20 m deep waters. Here, the asymmetrical bathymetry of the channel promotes a more intense turbulence field at the surface during the ebb tide. While all three wake features differ in composition, they all predictably create local zones of extreme turbulent flow structures and tern feeding flocks had been observed at all three features prior to the study. With various tern (Sterna sandvicensis, S. hirundo, S. paradisaea) colonies located across Strangford Lough, Swan island presents the nearest colony to any of these wake features (Fig. 1). Sandwich terns are most abundant with 776 AONs (Apparently Occupied Nests, which equates to the number of breeding pairs), followed by common (340 AONs) and Artic (193 AONs) terns, respectively (pers. comm. Hugh Thurgate, National Trust, Strangford Lough head ranger).

Data collection and analysis

A vantage point study was designed to collect count data of terns over the wake features between 18th July 2018 and 12th August 2018. Vantage points were located on the shore with a 200 m–1 km distance from each feature and covered an area of ~0.05 km² for each site to assess bird numbers associating with each localised wake feature. Observations covered all tidal states over a spring and neap tidal cycle. Using binoculars (Opticron Verano BGA HD and Nikon Monarch 10 × 42), counts of hovering or diving birds deemed foraging were completed every 2nd/3rd min for 15 min with a 5 min rest period to avoid observer fatigue (mean survey period across sites = 129 min, SD = 41 min). Number of surveys varied minimally per site, with Walter’s Rock (n = 9), SeaGen (n = 13) and Routen Wheel (n = 11) with a total observation time of 23.38 h, 25.26 h and 22.14 h, respectively. A general-additive mixed effect model (GAMM) was performed to quantify variances in the probability of encountering terns and the number of terns if encountered among tidal states and locations. A binomial model was used for the probability of encountering terns, and a negative binomial was used for the number of terns if encountered. Location was used as a categorical explanatory variable. Tidal state (hours after high water) was used as a continuous and non-linear explanatory variable. The number of knots was constrained to six to avoid over-fitting. Tidal state was also modelled as an interaction with location to account for differences in patterns among locations. An AR1 structure was used to account for temporal autocorrelation in model residuals within locations. Model parameters were used to predict variations in the probability of encountering terns and the number of terns if encountered across different locations and tidal states. Differences in probabilities and numbers across locations and tidal states were tested for significance (p < 0.05) using F-tests. Models were performed in the mgcv packages in R Statistics65.

UAV surveys

To record fine-scale foraging behaviour in relation to the wakes, UAV surveys were performed from the nearest accessible shore location to each feature using a DJI Mavic Pro quadcopter recording 4 K video at 25 fps. The UAV was flown manually using the DJI Go v4.0 application. In order to comply with best practices66 and minimise potential disturbance, the vertical ascent of the UAV was made at 200 m distance from the foraging aggregations and sampling was performed at a height of 120 m above-surface level, as measured by the on-board altimeter. Missions included transects across SeaGen, as well as hovering (holding station with a vertically downward-facing camera) over the flood wake of SeaGen to capture seabird flight tracks over time. Surveys reported here were conducted on 11 July 2018 during a flood tidal cycle (07:30 h – 08:30 h GMT) with a total flight time of 41 min. All missions were completed in accordance with local regulations and flown by the same qualified (UK Civil Aviation Authority) pilot. The UAV camera was calibrated in the lab and video sequences post-processed using MATLAB (R2017b; Mathworks). Georeferenced composite panoramic images captured the distribution of terns up-and downstream of SeaGen. Machine learning approaches were used to identify, count and track terns over SeaGen’s flood wake. Briefly, moving objects were detected using frame-to-frame differencing, segmentation and then filtered by size to remove sun-glint speckles and large foam patches. Images of potential targets were then passed through a trained “Bag of Features” classifier before using Kalman filters to compile tracks of those targets identified as terns only. The classifier was trained using 806 manually identified images each of foam and terns, with an average accuracy of 93% when applied to a validation set of 3764 images.

Acoustic doppler current profiler (ADCP) surveys

Vessel-mounted ADCP transects were performed on 13 Aug 2018 using a pole-mounted (1.15 m depth) RDI Workhorse Monitor broadband ADCP (600 kHz) in bottom-tracking mode with a vertical bin size of 1 m. All data was acquired using VMDas software (v. 1.46; RD Instruments, Inc.) and post-processed in WinADCP (v. 1.14; RD Instruments, Inc.). True current velocities were computed by subtraction of the bottom-tracked boat velocity. To quantify the acoustic scattering in the water column as a metric for macro-turbulence39, volume-backscattering strength (Sv in decibels, dB) was calculated across a maximum of 40 bins from the ADCP’s recorded raw echo intensity data using a working version of the sonar equation as originally described in Deines67 and updated by Mullison68. The backscatter equation accounts for two-way transmission loss, time-varying gain, water absorption, and uses an instrument- and beam-specific RSSI scaling factor to convert counts to decibels. This makes it a more robust measure of scattering compared to raw echo intensity, which can be more readily extracted from the ADCP. Sv was calculated for each bin along each of the four beams of the ADCP. For each range bin, the maximum of the four beams (Svmax) was taken to create depth profiles of the maximum level of scattering across the water column. In high-flow environments, high values of acoustic scattering are dominated by enhanced surface bubble entrainment and sediment re-suspension22,41,69.

Hydrodynamic modelling

The Strangford Lough hydrodynamic model developed using MIKE21 modelling software (DHI Water and Environment software package: www.dhisoftware.com)70 was used to simulate particle movement in the Narrows. In short, the model uses a finite volume method by solving a depth averaged shallow water approximation. Full details of the model setup can be found in Kregting and Elsäßer70. The Strangford Lough model was coupled to a particle tracking module that incorporates advection and dispersion resolved using the Langevin equation. For horizonal movement, in the absence of any dispersion (horizontal or vertical) information, the scaled eddy viscosity was used with the software recommended constant value of 1.0. For the vertical dispersion, a constant dispersion value of 0.01 m2 per second was used. Changes in flow velocity throughout the water column were calculated based on the bed friction velocity, a parameter calculated directly in the hydrodynamic model. Passive particles as proxy for microscopic or small organisms were released from the Irish Sea at a depth of 10 m, approximately half the water column height (Fig. 1). A trickle release approach was adopted where 200 particles were released every 5 min timestep on the flood tide only and the time taken from release to the time taken to reach SeaGen was noted.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset used to generate the main result shown in Fig. 2 is available online at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7732514.v171. All other data generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dafforn, K. A. et al. Marine urbanization: An ecological framework for designing multifunctional artificial structures. Front. Ecol. Environ. 13, 82–90 (2015).

Pinaud, D. & Weimerskirch, H. Scale-dependent habitat use in a long-ranging central place predator. J. Anim. Ecol. 74, 852–863 (2005).

Bertrand, A. et al. Broad impacts of fine-scale dynamics on seascape structure from zooplankton to seabirds. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–9 (2014).

Abrahms, B. et al. Mesoscale activity facilitates energy gain in a top predator. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20181101 (2018).

Miller, P. I., Scales, K. L., Ingram, S. N., Southall, E. J. & Sims, D. W. Basking sharks and oceanographic fronts: quantifying associations in the north-east Atlantic. Funct. Ecol. 29, 1099–1109 (2015).

Tew Kai, E. et al. Top marine predators track Lagrangian coherent structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8245–8250 (2009).

Scales, K. L. et al. Mesoscale fronts as foraging habitats: composite front mapping reveals oceanographic drivers of habitat use for a pelagic seabird. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140679 (2014).

Johnston, D. W. & Read, A. J. Flow-field observations of a tidally driven island wake used by marine mammals in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Fish. Oceanogr. 16, 422–435 (2007).

Thorne, L. H. & Read, A. J. Fine-scale biophysical interactions drive prey availability at a migratory stopover site for Phalaropus spp. in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 487, 261–273 (2013).

Zamon, J. E. Mixed species aggregations feeding upon herring and sandlance schools in a nearshore archipelago depend on flooding tidal currents. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 261, 243–255 (2003).

Braune, B. M. & Gaskin, D. E. Feeding ecology of nonbreeding populations of larids off Deer Island, New Brunswick. Auk 99, 67–76 (1982).

Urmy, S. S. & Warren, J. D. Foraging hotspots of common and roseate terns: the influence of tidal currents, bathymetry, and prey density. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 590, 227–245 (2018).

Cabot, D. & Nisbet, I. Terns. (Collins, London, UK, 2013).

Duffy, D. C. Predator-prey interactions between common terns and butterfish. Ornis Scand. (Scand. J. Ornithol. 19, 160–163 (1988).

Schwemmer, P., Adler, S., Guse, N., Markones, N. & Garthe, S. Influence of water flow velocity, water depth and colony distance on distribution and foraging patterns of terns in the Wadden Sea. Fish. Oceanogr. 18, 161–172 (2009).

Boyd, C. et al. Predictive modelling of habitat selection by marine predators with respect to the abundance and depth distribution of pelagic prey. J. Anim. Ecol. 84, 1575–1588 (2015).

Ladd, C., Jahncke, J., Hunt, G. L., Coyle, K. O. & Stabeno, P. J. Hydrographic features and seabird foraging in Aleutian Passes. Fish. Oceanogr. 14, 178–195 (2005).

Stevick, P. et al. Trophic relationships and oceanography on and around a small offshore bank. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 363, 15–28 (2008).

Waggitt, J. J. et al. Combined measurements of prey availability explain habitat selection in foraging seabirds. Biol. Lett. 14, 20180348 (2018).

Weimerskirch, H. Are seabirds foraging for unpredictable resources? Deep. Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 54, 211–223 (2007).

Hazen, E. L. et al. Scales and mechanisms of marine hotspot formation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 487, 177–183 (2013).

Nimmo-Smith, W. A. M., Thorpe, S. A. & Graham, A. Surface effects of bottom-generated turbulence in a shallow tidal sea. Nature 400, 251–254 (1999).

Shields, M. A. et al. Marine renewable energy: The ecological implications of altering the hydrodynamics of the marine environment. Ocean Coast. Manag. 54, 2–9 (2011).

Fraser, S., Nikora, V., Williamson, B. J. & Scott, B. E. Hydrodynamic impacts of a marine renewable energy installation on the benthic boundary layer in a tidal channel. Energy Procedia 125, 250–259 (2017).

Floeter, J. et al. Pelagic effects of offshore wind farm foundations in the stratified North Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 156, 154–173 (2017).

Churchfield, M. J., Li, Y. & Moriarty, P. J. A large-eddy simulation study of wake propagation and power production in an array of tidal- current turbines. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 371, 201204 (2013).

Rivier, A., Bennis, A. C., Pinon, G., Magar, V. & Gross, M. Parameterization of wind turbine impacts on hydrodynamics and sediment transport. Ocean Dyn. 66, 1285–1299 (2016).

Vanhellemont, Q. & Ruddick, K. Turbid wakes associated with offshore wind turbines observed with Landsat 8. Remote Sens. Environ. 145, 105–115 (2014).

Karman, T. Von The fundamentals of the statistical theory of turbulence. J. Aeronaut. Sci. 4, 131–138 (1937).

Creech, A. C. W., Borthwick, A. G. L. & Ingram, D. Effects of support structures in an LES actuator line model of a tidal turbine with contra-rotating rotors. Energies 10, 1–25 (2017).

Webb, P. W. Entrainment by river chub Nocomis micropogon and smallmouth bass Micropterus dolomieu on cylinders. J. Exp. Biol. 291, 2403–2412 (1998).

Liao, J. C. The Karman gait: novel body kinematics of rainbow trout swimming in a vortex street. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 1059–1073 (2003).

Tritico, H. M. & Cotel, A. J. The effects of turbulent eddies on the stability and critical swimming speed of creek chub (Semotilus atromaculatus). J. Exp. Biol. 213, 2284–2293 (2010).

Liao, J. C. A review of fish swimming mechanics and behaviour in altered flows. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 362, 1973–1993 (2007).

Cote, A. J. & Webb, P. W. Living in a turbulent world-A new conceptual framework for the interactions of fish and eddies. Integr. Comp. Biol. 55, 662–672 (2015).

Lupandin, A. I. Effect of flow turbulence on swimming speed of fish. Biol. Bull. 32, 461–466 (2005).

Hale, R. & Swearer, S. E. Ecological traps: Current evidence and future directions. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283, 1–8 (2016).

Martin, T. G. et al. Zero tolerance ecology: improving ecological inference by modelling the source of zero observations. Ecol. Lett. 8, 1235–1246 (2005).

Lieber, L., Nimmo-Smith, W. A. M., Waggitt, J. J. & Kregting, L. Fine-scale hydrodynamic metrics underlying predator occupancy patterns in tidal stream environments. Ecol. Indic. 94, 397–408 (2018).

Lavery, A. C., Chu, D. & Moum, J. N. Measurements of acoustic scattering from zooplankton and oceanic microstructure using a broadband echosounder. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 67, 379–394 (2010).

Holdaway, G. P., Thorne, P. D., Flatt, D., Jones, S. E. & Prandle, D. Comparison between ADCP and transmissometer measurements of suspended sediment concentration. Cont. Shelf Res. 19, 421–441 (1999).

Demer, D. A., Barange, M. & Boyd, A. J. Measurements of three-dimensional fish school velocities with an acoustic Doppler current profiler. Fish. Res 47, 201–214 (2000).

Zedel, L. & Cyr-Racine, F. -Y. Extracting fish and water velocity from Doppler profiler data. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 66, 1846–1852 (2009).

Russell, D. J. F. et al. Marine mammals trace anthropogenic structures at sea. Curr. Biol. 24, R638–R639 (2014).

Burke, C. M., Montevecchi, W. A. & Wiese, F. K. Inadequate environmental monitoring around offshore oil and gas platforms on the Grand Bank of Eastern Canada: Are risks to marine birds known? J. Environ. Manag. 104, 121–126 (2012).

Claisse, J. T. et al. Oil platforms off California are among the most productive marine fish habitats globally. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 111, 15462–15467 (2014).

Harvey, B. C. Susceptibility of young‐of‐the‐year fishes to downstream displacement by flooding. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 116, 851–855 (1987).

Behrens, J. W. & Steffensen, J. F. The effect of hypoxia on behavioural and physiological aspects of lesser sandeel, Ammodytes tobianus (Linnaeus, 1785). Mar. Biol. 150, 1365–1377 (2007).

Turnpenny, A. W. H. Swimming performance of juvenile sprat, Sprattus sprattus L., and herring, Clupea harengus L., at different salinities. J. Fish. Biol. 116, 851–855 (1983).

Masden, E. A. et al. Barriers to movement: Impacts of wind farms on migrating birds. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 66, 746–753 (2009).

Langton, R., Davies, I. M. & Scott, B. E. Seabird conservation and tidal stream and wave power generation: Information needs for predicting and managing potential impacts. Mar. Policy 35, 623–630 (2011).

Reynolds, S. J. et al. Long‐term dietary shift and population decline of a pelagic seabird—A health check on the tropical Atlantic? Glob. Chang. Biol. 00, 1–12 (2019).

Selot, F., Fraile, D. & Brindley, G. Offshore Wind in Europe -Key Trends and Statistics 2018. (Wind Europe, 2018). https://windeurope.org/about-wind/statistics/offshore/european-offshore-wind-industry-key-trends-statistics-2018/

Grashorn, S. & Stanev, E. V. Kármán vortex and turbulent wake generation by wind park piles. Ocean Dyn. 66, 1543–1557 (2016).

Ouro, P., Runge, S., Luo, Q. & Stoesser, T. Three-dimensionality of the wake recovery behind a vertical axis turbine. Renew. Energy 133, 1066–1077 (2019).

Hamzah, B. A. International rules on decommissioning of offshore installations: Some observations. Mar. Policy 27, 339–348 (2003).

Bell, N. & Smith, J. Coral growing on North Sea oil rigs. Nature 402, 601 (1999).

Macreadie, P. I., Fowler, A. M. & Booth, D. J. Rigs-to-reefs: Will the deep sea benefit from artificial habitat? Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 455–461 (2011).

Fox, C. J., Benjamins, S., Masden, E. A. & Miller, R. Challenges and opportunities in monitoring the impacts of tidal-stream energy devices on marine vertebrates. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 1926–1938 (2018).

Miller, R. G. et al. Marine renewable energy development: Assessing the benthic footprint at multiple scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 433–440 (2013).

Heery, E. C. et al. Identifying the consequences of ocean sprawl for sedimentary habitats. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 492, 31–48 (2017).

Inger, R. et al. Marine renewable energy: Potential benefits to biodiversity? An urgent call for research. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 1145–1153 (2009).

Fowler, A. M., Macreadie, P. I., Jones, D. O. B. & Booth, D. J. A multi-criteria decision approach to decommissioning of offshore oil and gas infrastructure. Ocean Coast. Manag. 87, 20–29 (2014).

Fowler, A. M. et al. Environmental benefits of leaving offshore infrastructure in the ocean. Front. Ecol. Environ. 571–578 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1827

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R 2nd edn (Chapman and Hall/CRC Press, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00905_3.x

Hodgson, J. C. & Koh, L. P. Best practice for minimising unmanned aerial vehicle disturbance to wildlife in biological field research. Curr. Biol. 26, R404–R405 (2016).

Deines, K. L. Backscatter estimation using Broadband acoustic Doppler current profilers. Proc. IEEE Sixth Work. Conf. Curr. Meas. (Cat. No. 99CH36331) 249–253 (IEEE, San Diego, CA, USA 1999). https://doi.org/10.1109/CCM.1999.755249

Mullison, J. Backscatter Estimation Using Broadband Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers-Updated. Application Note. 8–13 (Teledyne RD Instruments FSA-031 cr, 2017).

Lavery, A. C., Geyer, W. R. & Scully, M. E. Broadband acoustic quantification of stratified turbulence. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134, 40–54 (2013).

Kregting, L. & Elsäßer, B. A Hydrodynamic modelling framework for strangford lough part 1: Tidal model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2, 46–65 (2014).

Lieber, L. et al. SightingData_Terns.csv. (2019). https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7732514.v1

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the PowerKite project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 654438, as well as a Queen’s University Belfast fellowship awarded to L.K.. J.J.W. is supported through the Marine Ecosystems Research Programme (MERP: NE/L003201/1), which is funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (NERC/DEFRA). We would like to acknowledge the support given by Pál Schmitt during ADCP data collection. We also wish to thank Jeremy Rogers, Simon Rogers and Oliver Rogers from Cuan Marine Services for boat time, seamanship and their in-depth knowledge of the Narrows tidal channel necessary for this study’s survey methodology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. conceived the ideas and all authors designed aspects of the methodology. L.K. managed the project. L.L. and J.J.W. collected the vantage point data; W.A.M.N.S. collected the UAV data (CAA-approved pilot) and L.L. collected the ADCP data. All authors performed analysis and interpreted the results. L.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave the final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lieber, L., Nimmo-Smith, W.A.M., Waggitt, J.J. et al. Localised anthropogenic wake generates a predictable foraging hotspot for top predators. Commun Biol 2, 123 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0364-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0364-z

This article is cited by

-

Fish response to the presence of hydrokinetic turbines as a sustainable energy solution

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.