Abstract

Spin-dependent scattering from magnetic impurities inside a superconductor gives rise to Yu-Shiba-Rusinov (YSR) states within the superconducting gap. They can be modeled by the largely equivalent Kondo or Anderson impurity models. The role of the magnetic and nonmagnetic properties of the impurity in relation to the coupling to the substrate is still under debate. Here, we use a scanning tunneling microscope to make a quantitative connection between the energy of a YSR state and the impurity-substrate hybridization. We corroborate the impurity substrate coupling as a key energy scale for surface derived YSR states using the Anderson impurity model. By combining experimental data from YSR state spectra and additional conductance measurements, we can determine on which side of the quantum phase transition the system resides. We thus provide a crucial step towards a more quantitative understanding of the crucial role of impurity substrate coupling utilizing the Anderson model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The impurity problem is one of the most extensively studied phenomena in condensed matter physics because it not only caters to fundamental interest in the local perturbation of a host material, but also has technological relevance in the design of specific properties through doping. The impact of impurities on the host material is broad ranging from having no effect for weak non-magnetic impurities in an s-wave superconductor (Anderson theorem)1,2 to creating complex many-body interactions between a magnetic impurity in a normal conducting host (Kondo effect)3. Somewhere in between, we find the so-called Yu-Shiba-Rusinov (YSR) states4,5,6, which arise from magnetic impurities in a superconducting host. YSR states have been quite successfully modeled as a combination of spin-dependent and spin-independent scattering potentials within the Kondo impurity model (see Fig. 1a)7,8,9. As such, this YSR model provides a simple and straightforward framework that has gone quite far in explaining numerous observations.

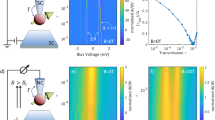

a In the Kondo impurity model, the YSR state arises owing to scattering from a spin-dependent impurity potential. b In the Anderson impurity model, the Yu-Shiba-Rusinov (YSR) state arises owing to hopping to and from an impurity state. c Energy diagram of the Anderson impurity model. The coupled impurity features an occupied state below the Fermi level at −EJ + EU and an unoccupied state above the Fermi level at EJ + EU, where EJ is the level splitting and EU is the level offset. Γs is the coupling strength. d Spectral functions of the two Anderson impurity states in the normal conducting state. There is significant overlap between these two states. e The resulting YSR states in the superconducting regime. Note the difference in energy scale between d and e. The spectra were calculated with a broadening parameter of γ = 10 μeV.

It is obvious that surface adsorbed impurities have more spatial degrees of freedom to relax when hybridizing with the host than bulk impurities. Impurity-substrate hybridization, however, is only implicitly contained in the Kondo impurity model10, which we also consider here at the mean field level. A more-detailed description is offered by the largely equivalent, albeit more general, Anderson impurity model (see Fig. 1b–e). It explicitly introduces an impurity-substrate hybridization parameter Γs, which plays a key role for the adsorption of impurities at surfaces. The Anderson impurity model also has the added benefit that it encompasses the Kondo effect as well as Andreev bound states, into which YSR states are embedded in a more general context11,12,13,14. In fact, this model provides a benchmark for the analysis of Josephson and Andreev transport through quantum dots (for a review, see ref. 15). Also, as tunneling is often understood as going through the impurity (i.e., the YSR state), the impurity-substrate coupling will influence the conductance as well, which can be modeled much better within the Anderson impurity model16. In order to ascertain these relations, a quantitative connection between the impurity-substrate hybridization and the behavior of the YSR state is needed.

Here, we demonstrate this relationship by a quantitative comparison of experimental data obtained from different measurements, which we connect through the Anderson impurity model: The binding energy of the YSR state for surface adsorbed impurities does not just depend on the intrinsic magnetic and non-magnetic properties of the impurity, but also largely depends on the coupling between the impurity and the substrate. We use ultralow temperature scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) at 10 mK to probe YSR states in intrinsic surface impurities on a superconducting V(100) substrate with a superconducting vanadium tip. Approaching the tip to an impurity with a YSR state induces an interaction between the tip and the impurity (e.g., attractive force17,18), which manifests itself as a change in the binding energy of the YSR state. A similar behavior in agreement with this picture has been observed in a number of systems19,20,21,22,23. However, although this behavior has been qualitatively attributed to a decrease21 as well as an increase22 in impurity-substrate coupling, so far a clear quantitative connection to specific microscopic energy scales has experimentally not been confirmed. Using the Anderson impurity model in the mean field approximation, we are able to quantify the relation between the change in the YSR state binding energy and the impurity-substrate coupling. We independently confirm the change in the impurity-substrate coupling through the distance dependence of the normal state conductance.

Further, we use this connection between impurity-substrate coupling and normal state conductance to determine, whether the YSR state is in the weak or strong scattering regime. For weak impurity-substrate coupling, the spin-dependent scattering potential will be weak and the impurity spin will be unscreened. As the impurity-substrate coupling increases, the system undergoes a quantum phase transition to a screened impurity spin in a strong scattering potential7,8,9. We demonstrate how to apply this model to determine on which side of the quantum phase transition the system is, which is a priori impossible to judge from the tunneling spectrum alone due to the symmetry of the YSR state energies in the spectral function.

Results

Distance dependence of YSR states

We use V(100) as sample and vanadium as tip, both of which are well superconducting at our experimental temperature. The gap parameter of vanadium in the sample as well as in the tip is Δs = Δt = 760 μeV unless otherwise noted (for experimental details, see “Methods” and Supplementary Note 1). Some intrinsic impurities on the surface generate YSR states. Some of the YSR states change their energy as a function of tip-sample distance. One example is shown in Fig. 2a–e. In Fig. 2a, a series of differential conductance spectra is shown as a function of tip-sample distance (z-position). A single pair of YSR states can be identified inside the gap (marked by YSR arrows), which changes its energy position as a function of z-position. The observation of coherence peaks (marked by Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) arrows) at Δt + Δs is an indication that there is a second transport channel not featuring a YSR state inside the gap, which will be discussed in more detail below. The energies at which the YSR states are observed have been extracted and plotted as a function of tip-sample distance in Fig. 2b.

a Series of normalized differential conductance spectra through an impurity with YSR states measured with a superconducting tip as function of tip-sample distance (z-position). The YSR states move, whereas the coherence peaks at Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) gap edge do not. At closer distances (bottom), higher order phenomena (Josephson effect at zero voltage and multiple Andreev processes near the YSR states) are visible. b Extracted YSR state energies as function of tip-sample distance. c Scaled coupling parameter \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{s}\) calculated from b. The values for \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{s}^{\,\text{alt}\,}\) have been calculated by exchanging ε+ ↔ ε− (for details see text). d Fit of a differential conductance spectrum at low conductance, where higher order processes are suppressed. We fit two channels, one of which probes the YSR state and the other probes an empty gap. e Density of states of the YSR state and the empty BCS gap as used in the fit in d.

The YSR state at positive (negative) bias voltage has been plotted in red (blue). As we will show below, the YSR states are in the strong spin-dependent scattering limit beyond the quantum phase transition7. In that regime, that branch of YSR states with positive values in the weak scattering limit (ϵ+ > 0, called positive branch in the following) has moved to negative energies, ϵ+ < 0, as shown in Fig. 2b. A priori, however, it is not possible to say on which side of the quantum phase transition the YSR state is in each case. A more-detailed analysis of the YSR state properties as function of tip-sample distance is necessary. For this, we have acquired different spectra along the z axis (tip-sample distance) and over a distance of ~470 pm, which corresponds to a change in tunneling current of about four orders of magnitude. Yet, we have stayed mostly in the tunneling regime (see below). Only in the last part, we find total transmissions τ > 0.1, where higher order processes are observed and the opening of additional transport channels becomes more likely.

Distance dependence of the conductance

In the following, we will express the normal state conductance GN in terms of the transmission τ = GN/G0 (GN: normal state conductance; G0 = 2e2/h: quantum of conductance; e: elementary charge; h: Planck constant), which simply references GN to the quantum of conductance. We extract the normal state conductance sufficiently away from the gap where the properties of the normal state are recovered. In this regime, the conductance is largely independent of bias voltage. The evolution of the transmission τexp corresponding to the data set in Fig. 2a is shown in Fig. 3a as a function of tip-sample distance (z-position). Its behavior is dominated by the exponential increase in the tunnel coupling between tip and impurity. However, we will show below that there are deviations from the exponential behavior, which are related to the changes in the impurity-substrate coupling (see Fig. 3b). A justification, why these changes are related to the impurity-substrate coupling is given in the Supplementary Note 2. The transport current through the impurity does not only depend on the tunnel coupling between the tip and the impurity, but also on the coupling between the impurity and the substrate16. These deviations nicely explain the changes in the YSR state energies. The Anderson model in the mean field approximation is ideally suited to provide a unified description of these observations. As the impurity-substrate coupling is an explicit parameter, we can establish a direct relation between the YSR state energy and the changes in the transmission τ (i.e., the normal state conductance GN). This is not easy to do within the Kondo impurity model.

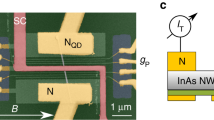

a Experimental normal state transmission τexp = GN/G0 as function of tip-sample distance. The exponential dependence is clearly visible. b Zoom-in, where the tip is close to the sample. The measured transmission τexp (blue) is compared to a transmission assuming an impurity-substrate coupling that is constant (τ0, yellow) and one that changes like \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\text{s}}\) as calculated from the corresponding YSR energies. c The tip probes two channels to the impurity, one of which is leading through the YSR state and the other through an empty BCS gap. Both channels couple to the substrate through the same impurity-substrate channel(s) Γs. d Reduced transmission \({\tau }_{\text{exp}}/{\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\text{t}}\) with the data labeled as in b.

Anderson impurity model

The Anderson impurity model has been successfully applied to a number of impurity problems involving magnetic as well as non-magnetic impurities24. It allows correlation effects to be taken into account to different degrees of complexity12,25. For the case that we consider here, where the Kondo temperature is typically smaller than the superconducting gap, a mean field approximation becomes appropriate, as shown in refs. 26,27.

A schematic energy diagram is shown in Fig. 1c. The system is described by the superconducting substrate (left) and the impurity having one occupied level at −EJ + EU and one unoccupied energy level at EJ + EU (right), which are coupled to the substrate by the impurity-substrate coupling parameter Γs. The energy EJ describes an effective Zeeman splitting and EU is an energy shift accounting for particle-hole asymmetry (EU = 0 implies particle-hole symmetry). Here, we restrict ourselves to using the energies EJ and EU as fit parameters, keeping in mind that a self-consistent treatment of the spin density of states may provide more insight on the origin of the magnetic properties as well as spin fluctuations in the impurity on the substrate.

The Green’s function of the impurity in the mean field Anderson impurity model can be straightforwardly written in 2 × 2 Nambu space as

where σi are the Pauli matrices. We assume that the coupling between tip and impurity is much smaller than the coupling between impurity and sample, i.e., τ ≪ 1, such that we can ignore it in this calculation. Further, gsc(ω) is the dimensionless Green’s function of the superconducting substrate (normalized to the density of states) with

where Δs is the order parameter of the substrate and γ is a phenomenological broadening parameter (cf. Dynes et al.28). For more details, refer to Supplementary Note 3.

The spectral function A(ω) = −ImTr’G(ω) of Eq. (1) features two impurity states at −EJ + EU and EJ + EU each having a width 2Γs (cf. Fig. 1d for the normal conducting state) along with a superconducting gap having an order parameter Δs and possibly extremely sharp pairs of subgap states depending on the relation between the parameters EJ, EU, Γs, and Δs (cf. Fig. 1e for typical YSR states inside the superconducting gap). Here, Tr’ denotes the trace with a change in sign for the energy axis in the hole part of the Green’s function.

For the purpose of analyzing the above data, we reduce the generality of Eq. (1) by assuming strong impurity-substrate coupling, i.e., Γs ≫ Δs. This assumption generally holds for surface adsorbed impurities and reflects the conditions, in which the YSR states within the Kondo impurity model are described. The resulting Green’s function is

without broadening parameter, which can be included by ω → ω + iγ. The energies ε± of the YSR states are located, where G(ω) becomes singular:

which has a very similar structure as the result from the Kondo impurity model. The similarity becomes even more obvious when simplifying Eq. (4) by assuming particle-hole symmetry, i.e., EU = 0,

The parameter J is the spin-dependent scattering potential in the Kondo impurity model with \(J=\frac{1}{2}{n}_{0}js\) in the classical limit, where n0 is the density of states in the substrate, j is the exchange coupling, and s is the impurity spin7,8,9. The parameters describing the YSR states in the Anderson impurity model and the Kondo impurity model are related through the Schrieffer–Wolff-like transformation in the strong coupling limit (cf. refs. 10,12).

For the following data analysis, we assume that the parameters that are more related to the intrinsic properties of the impurity EJ and EU are constant as function of tip-sample distance, whereas the impurity-substrate coupling Γs can vary. This is a sensible assumption of some generality, which has been used before in a somewhat different context for YSR states in molecules adsorbed on a superconducting surface23,29. However, we have to keep in mind that in a self-consistent treatment EJ becomes a function of Γs, which may lead to small corrections. We also assume particle-hole symmetry (i.e., EU = 0), which is justified because we can show that EU is small compared with Γs (see Supplementary Note 3). In the case of strongly asymmetric YSR states (for example in Fig. 2), a non-zero EU term may result in further corrections. Using the branch ε+, we find for the impurity-substrate coupling

The symmetry of the YSR state energies makes it a priori impossible to decide, on which side of the quantum phase transition the system is, i.e., if Γs < EJ or Γs > EJ. Therefore, aside from the coupling Γs, we calculate an alternative coupling \({\Gamma }_{\,\text{s}}^{\mathrm{alt}\,}\) by exchanging the values ε+ ↔ ε−, which changes effectively from one side to the other side of the quantum phase transition.

Using Eq. (7), we calculate the distance-dependent coupling Γs and \({\Gamma }_{\,\text{s}}^{\mathrm{alt}\,}\). The results are shown in Fig. 2c in units of EJ, for which we define the scaled coupling \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{s}}={\Gamma }_{\mathrm{s}}/{E}_{\mathrm{J}}\) and \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\,\text{s}}^{\mathrm{alt}}={\Gamma }_{\mathrm{s}}^{\mathrm{alt}}/{E}_{\mathrm{J}}\). We can see directly, that for the \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{s}}\) branch the coupling reduces as the tip-sample distance reduces. Such a behavior can be expected, if attractive forces from the tip pull the impurity away from the substrate in the tunneling regime18,21. However, concomitant circumstances, e.g., changes in the local density of states, may just as well result in an increase in coupling, yielding the behavior described by the \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\,\text{s}}^{\mathrm{alt}\,}\) data22,30. We will directly address this point below by implementing a model to link the extracted impurity-substrate coupling to the measured normal state conductance (i.e., transmission).

In the following, we will show that analyzing the evolution of both the impurity-substrate coupling Γs and the transmission τ as function of tip-sample distance z, we are able to determine, on which side of the quantum phase transition the system is.

Distance dependence of the impurity-substrate coupling

The transmission τ of the junction not only depends on the tunneling between tip and impurity but also on the coupling between impurity and substrate. The latter may change when the distance z between tip and impurity is tuned owing to attractive or repulsive forces between tip and impurity. In addition, an understanding of the distance dependence GN(z) requires an analysis of possible transport channels involved, which we discuss in the following.

As can be seen in Fig. 1e, YSR states alone give rise to two distinct peaks in the density of states completely quenching the coherence peaks. This is in contrast to our experimental observations depicted in Fig. 2d, where two additional peaks appear at ±(Δt + Δs) as coherence peaks in the spectrum. We conclude that we have to assume two transport channels, which we assume to be independent. Microscopically, we envision these two channels as coming from two different orbitals, one of which features a YSR state owing to the interaction with the substrate and the other does not (cf. Fig. 3c).

Accordingly, we calculate the total transmission τ as the sum of the two contributions (assuming that EU = 0)

where p is the relative signal contributions and Γt = Γt0exp[−(z − z0)/z1] is the exponentially varying tunnel coupling between the tip and the impurity (for details and why we use the same decay constant z1 for both channels see Supplementary Note 4). The parameters Γt0 and z1 are the only fit parameters to model the transmission, whereas z0 just represents the arbitrary position of the origin of the z axis. The two fit parameters can be determined in the regime, where the tip is far away from the sample, such that the influence on the impurity-substrate coupling is smallest. We further assume that the two different channels use the same impurity-substrate channel(s), which is illustrated in Fig. 3c. Note the explicit dependence of the GYSR on EJ, which is absent in GBCS, indicating the quite different nature of these two transport channels.

The red line in Fig. 2d shows a fit to the spectrum involving a transport channel through the YSR state along with a channel through an empty BCS gap (for details of the fitting, see Supplementary Note 5). The individual densities of states for the YSR state (red) and the BCS gap (blue) are shown in Fig. 2e. In the following, we will assume that these two orbitals have the same decay constant into the vacuum in order to keep the model simple. The fit (red line in Fig. 2d) reveals that 22% of the signal (referenced to the normal state conductance GN, i.e., the total transmission τ, at high bias voltage) is contributed from the YSR state channel and 78% of the signal comes from the empty BCS gap channel. We are now in a position to compare the experimental data for GN(z) with predictions obtained from the above model (Eqs. (7) and (8)).

The measured transmission τexp is shown in Fig. 3a over about four orders of magnitude. Changes in the exponential behavior are difficult to detect in this graph. A zoom-in to the closer tip-sample distance is shown in Fig. 3b, where changes in the exponential behavior are most pronounced. Assuming no change in the impurity-substrate coupling, i.e., Γs = const, we calculate the transmission τ0 from Eq. (8), which is shown as a yellow line in Fig. 3b. For the decay constant z1, we fit a value of 51.6 pm. The experimental transmission τexp clearly increases more than for a constant impurity-substrate coupling. From Eq. (8), we conclude that this can only be explained by a decreasing impurity-substrate coupling, as GN is roughly inversely proportional to Γs. Using the values for Γs (cf. Fig. 2c) in Eq. (8), we plot the resulting transmission τs as a red line in Fig. 3b. We find much better agreement with the experimental data τexp than for the constant impurity-substrate coupling.

Still, the exponential increase of the transmission owing to the tunnel coupling masks the agreement. We, therefore, divide all transmission curves by the normalized tunnel coupling \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{t}}={\Gamma }_{\mathrm{t}}/{E}_{\mathrm{J}}\) in order to accentuate changes in the exponential dependence. The resulting curves are shown in Fig. 3d. The deviations from the constant impurity-substrate coupling τ0 become more obvious now. The experimental data τexp show a steady increase as the tip-sample distance decreases significantly deviating from the constant coupling model. The transmission τs based on the Γs data values extracted from the YSR energies clearly follows the experimental data. We find generally very good agreement, from which we conclude that assigning the negative YSR energy branch in Fig. 3b to ϵ+ is consistent with a decrease of the impurity-substrate coupling as the tip-sample distance decreases and that the system is in the strong scattering regime.

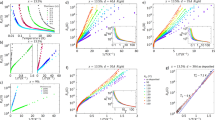

Moving across the quantum phase transition

As another example, we have chosen an intrinsic impurity, for which the YSR state moves across the quantum phase transition, i.e., the energies cross the zero energy line, when decreasing the tip-sample distance. A differential conductance spectrum with a high point density along the voltage axis (blue) is shown in Fig. 4a. The YSR states (inner peaks) can be very well seen along with the BCS peaks (outer peaks). The fit (red) again consists of two channels, where 39% of the signal is contributed from the YSR state channel and 61% of the signal comes from the empty BCS gap channel.

a Differential conductance spectrum of a YSR state (blue). The fit (red) considers two channels, one through the YSR state and one through an empty BCS gap. b YSR state energy positions as function of tip-sample distance extracted from a data set with high point density along the distance direction. The two branches cross zero energy indicating that they move across the quantum phase transition. c Scaled impurity-substrate coupling calculated from the YSR state energies in b. d The reduced transmission \({\tau }_{\text{exp}}/{\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\text{t}}\) emphasizes the deviation of the experimental data τexp compared with the model with constant coupling τ0. We find good agreement with the branch τs, where the impurity-substrate coupling decreases during the tip approach.

The extracted YSR state energies are plotted in Fig. 4b, where the crossing of the energy branches at zero energy is clearly visible. Again, it is a priori not possible to decide from which side the system moves across the quantum phase transition. Therefore, we calculate both possibilities for the scaled coupling parameters \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{s}}\) and \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\,\text{s}}^{\mathrm{alt}\,}\), which are plotted in Fig. 4c, where one branch increases, whereas the other branch decreases as function of tip-sample distance.

The excellent agreement between the experiment and the calculation is again accentuated by plotting the transmission curves divided by the normalized exponential tunnel coupling \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{t}}\), which is shown in Fig. 4d. Comparing τexp to the transmission τ0 with constant impurity-substrate coupling Γs = const, we find poor agreement. The transmission τs based on the Γs values follows the experimental data very well indicating that the YSR state moves across the quantum phase transition from the strong scattering regime to the weak scattering regime, as we move closer with the tip to the sample. For the tunnel coupling \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{t}}\), we find a decay constant z1 = 49.15 pm. The full transmission dependence can be found in Supplementary Note 6.

Increasing impurity-substrate coupling

As a third example, we found that some of the intrinsic impurities show an increasing impurity-substrate coupling as the tip-sample distance decreases. The image showing the differential conductance spectra as function of applied bias voltage and tip-sample distance (z-position) is plotted in Fig. 5a. Again the inner peaks are the YSR state and the outer peaks are the BCS coherence peaks. The YSR peaks move towards zero energy as the tip approaches the impurity, whereas the BCS coherence peaks do not move. The extracted YSR state energies are shown in Fig. 5b with both energy branches shown. Using Eq. (7), we calculate the scaled hopping for both situations \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{s}}\) and \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\,\text{s}}^{\mathrm{alt}\,}\) (Fig. 5c, d shows the transmission curves divided by the normalized exponential tunnel coupling \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{t}}\). Comparing τexp with the transmission τ0 with constant impurity-substrate coupling Γs = const, we find again poor agreement. We note that the experimental transmission τexp evolves below the calculated transmission τ0 (yellow line). This indicates that the impurity-substrate coupling actually increases when approaching the tip to the sample. The transmission τs based on Γs follows the experimental data very well. Here, \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{s}}\) actually increases with decreasing tip-sample distance. For the tunnel coupling \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm{t}}\), we find a decay constant z1 = 52.3 pm. The trend clearly indicates that the impurity-substrate coupling increases as we approach with the tip to the sample. This means that the YSR state is in the weak scattering regime. The full transmission dependence can be found in Supplementary Note 6.

a Series of differential conductance spectra (normalized) through an impurity with YSR state measured with a superconducting tip as function of tip-sample distance (z-position). The YSR states move (inner peaks), while the coherence peaks (BCS) do not (outer peaks). At closer distances, higher order phenomena (Josephson effect at zero voltage and multiple Andreev processes near the YSR states) are visible. b YSR state energy positions as function of tip-sample distance extracted from the data set in a. c Scaled impurity-substrate coupling calculated from the energies in b. d The reduced transmission \({\tau }_{\text{exp}}/{\tilde{\Gamma }}_{\text{t}}\) emphasizes the deviation of the experimental data τexp compared with the model with constant coupling τ0. We find good agreement with the branch τs, where the impurity-substrate coupling increases during the tip approach.

Discussion

Measuring the normal state conductance (i.e., the transmission) along with the YSR state energy as a function of tip-sample distance allows us to extract very valuable information, such as an increase or decrease in the impurity-substrate interaction, experimentally without resorting to ab initio calculations. The details of the interaction mechanism with the tip and the corresponding change in the impurity-substrate interaction need not be known for an assessment of the coupling regime. We were able to identify on which side of the quantum phase transition the system is for all three examples. In addition, this method can easily be extended to other scenarios presented in the literature19,20,21,22,23.

The three examples present different (non-exhaustive) scenarios that can be found when YSR states move in energy as the tip is approaching the impurity. The results are summarized in Fig. 6, where the energies of the YSR states are plotted as function of the scaled coupling Γs/EJ. With the analysis presented above, we can now indicate the coupling range for each example as a black bar labeled by the figure number, where the data set is discussed. Note that the evolution of the YSR state energies and their crossing at the transition point (Γs = EJ) nicely illustrates the ambiguity in determining the scattering regime, if the analysis were solely based on the energy position of the YSR state. Applying a magnetic field is the only other possibility so far to find the scattering regime for YSR states11.

For small coupling Γs < EJ (Γs is impurity-substrate coupling and EJ is the level splitting) scattering is weak and the YSR peaks move towards zero for increasing coupling. At zero energy, where Γs = EJ, the system undergoes a quantum phase transition into the strong scattering regime. In the strong coupling regime, where Γs > EJ, the YSR energies move away from zero as the coupling increases. The range of coupling values in the different data sets are indicated as black wedges with the thinner end indicating a smaller tip-sample distance.

The excellent agreement between the measured and calculated normal state transmission τ clearly identifies the impurity-substrate coupling Γs as the dominant energy scale responsible for changing the energy of surface derived YSR states as function of tip-sample distance. This is further corroborated by the conduction channel analysis, showing that the dominant part of the current goes through the empty gap channel, which is unaffected by the magnetic properties of the YSR channel. The intrinsic magnetic properties of the adsorbate remain unchanged at the surface to lowest approximation. This also validates the delicate interplay between the intrinsic magnetic properties of the adsorbate and its interaction with the superconducting host as the responsible mechanism for placing the YSR states inside the gap and even driving them through the quantum phase transition, depending on their adsorption site29,31,32,33,34 as well as the tip-sample distance19,20,21,22,23.

We find very similar decay constants z1 for the tunnel coupling for all three examples between 49.15 pm and 52.3 pm lying within a few percent, which shows that the different examples feature very similar impurities. Interestingly, we have made no explicit assumption about the distance dependence of the impurity-substrate coupling. The impurity-substrate coupling is calculated from the YSR energies and matches well with the conductance (transmission) change as function of tip-sample distance. This provides a pathway for learning more about the impurity-substrate coupling and the bond strength in particular as function of bond length (i.e., impurity-substrate distance). Force–distance measurements in a combination of STM with atomic force microscopy (AFM) could provide further insight on the tip-sample interaction as well as the impurity-substrate coupling18.

The Anderson impurity model naturally takes into account the impurity-substrate hybridization through an explicit parameter, which is only implicitly contained in the Kondo impurity model. This is important as the surface provides much less-constrained boundary conditions for adsorption and relaxation than the much higher coordination requirements in the three-dimensional bulk. Furthermore, the Anderson model enables a more-detailed description of the tunneling process through the impurity, which is largely assumed in the tunneling through YSR states. It provides a direct connection between the impurity-substrate coupling and the normal state conductance, which allows for a direct comparison with experimental data and thus adds deeper understanding of YSR states at surfaces. Although largely equivalent, we, therefore, promote the Anderson impurity model as the preferred model for surface adsorbed impurities.

Putting the mean field approximation of the Anderson impurity model into the context of other existing models for YSR states, in the strong impurity-substrate coupling limit it connects well with the Kondo impurity model4,5,6,7,8,9,35 and in the weak impurity-substrate coupling limit it connects to the more general Andreev bound states36. Further, it allows us to including correlations (Kondo effect) by going beyond the mean field approximation12,13,14,15,23,24,25,29, and it extends to a regime, where the impurity-substrate coupling plays a decisive role, i.e., for impurities at surfaces.

Conclusion

We have presented direct experimental evidence that the impurity-substrate coupling for adsorbates at surfaces presents an important energy scale largely responsible for the detailed behavior of surface derived YSR states. The behavior of the impurity-substrate coupling (decrease or increase) can be extracted experimentally through the normal state conductance (i.e., transmission) without knowing the details of the actual mechanism and the tip-impurity interaction. It can be used to diagnose, on which side of the quantum phase transition the system is (see Supplementary Note 7). Using the mean field approximation of the Anderson impurity model, we were able to make a direct connection between the accompanying change in the YSR state energy and the change in the impurity-substrate coupling for which it provides an explicit parameter. This connection was evidenced through the explicit calculation of the normal state conductance (i.e., transmission), which is nicely implemented with the Anderson impurity model because it provides a description of tunneling through the impurity directly.

Our results provide an intriguing point of view on the surface induced YSR states and their interactions with the underlying substrate with many possibilities for a deeper understanding provided by the complementary, but more-detailed mean field approximation of the Anderson impurity model. The Anderson impurity model provides the basis for moving away from the classical spin model in YSR states and establishing a better link between the experimental observations and the theoretical models, in particular for surface induced YSR states as well as in the presence of the various manifestations of the Kondo effect.

Methods

We prepare single crystal V(100) surfaces through cycles of sputtering and annealing (700 ∘C). Owing to the intrinsic presence of oxygen in the bulk (99.8% purity) and aggregation to the surface during annealing, the surface features a (5 × 1) reconstructed oxygen layer. The most abundant impurities visible in STM topography image are most likely oxygen vacancies, whereas carbon is also expected to have a non-negligible concentration that, however, is not directly visible. Some of the oxygen vacancies in a certain chemical environment, feature single and well defined intrinsic YSR states. Owing to the complexity of the surface and various possibilities of the internal structure of the impurity, the YSR states show wide-spread energy distribution and different response to tip approach37,38 (for details, see Supplementary Note 1). The experiments have been performed in ultra high vacuum and at a base temperature of 10 mK. For all spectra measured, the tip was stabilized at 4 mV bias voltage at different setpoint current to achieve various conductance, and the dI/dV signal was recorded using standard a lock-in technique with amplitude 20 μV.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Anderson, P. W. Theory of dirty superconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 11, 26–30 (1959).

Abrikosov, A. A. & Gor’kov, L. P. Superconducting alloys at finite temperature. JETP 9, 220–221 (1959).

Kondo, J. Resistance minimum in dilute magnetic alloys. Prog. Theor. Phys. 32, 37–49 (1964).

Yu, L. Bound state in superconductors with paramagnetic impurities. Acta Phys. Sin. 21, 75–91 (1965).

Shiba, H. Classical spins in superconductors. Prog. Theor. Phys. 40, 435–451 (1968).

Rusinov, A. I. Superconductivity near a paramagmetic impurity. JETP Lett. 9, 85–87 (1969).

Salkola, M. I., Balatsky, A. V. & Schrieffer, J. R. Spectral properties of quasiparticle excitations induced by magnetic moments in superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 55, 12648–12661 (1997).

Flatté, M. E. & Byers, J. M. Local electronic structure of defects in superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 56, 11213–11231 (1997).

Flatté, M. E. & Byers, J. M. Local electronic structure of a single magnetic impurity in a superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3761–3764 (1997).

Schrieffer, J. R. & Wolff, P. A. Relation between the Anderson and Kondo hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. 149, 491–492 (1966).

Žitko, R., Bodensiek, O. & Pruschke, T. Effects of magnetic anisotropy on the subgap excitations induced by quantum impurities in a superconducting host. Phys. Rev. B 83, 054512 (2011).

Žitko, R., Lim, J. S., Lóez, R. & Aguado, R. Shiba states and zero-bias anomalies in the hybrid normal-superconductor Anderson model. Phys. Rev. B 91, 045441 (2015).

Kadlecová, A., Žonda, M. & Novotný, T. Quantum dot attached to superconducting leads: Relation between symmetric and asymmetric coupling. Phys. Rev. B 95, 195114 (2017).

Kadlecová, A., Žonda, M., Pokorný, V. & Novotný, T. Practical guide to quantum phase transitions in quantum-dot-based tunable Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 044094 (2019).

Martín-Rodero, A. & Yeyati, A. L. Josephson and Andreev transport through quantum dots. Adv. Phys. 60, 899–958 (2011).

Cuevas, J. C. & Scheer, E. Molecular Electronics (World Scientific, 2010).

Ternes, M., Lutz, C. P., Hirjibehedin, C. F., Giessibl, F. J. & Heinrich, A. J. The force needed to move an atom on a surface. Science 319, 1066–1069 (2008).

Ternes, M. et al. Interplay of conductance, force, and structural change in metallic point contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 016802 (2011).

Ternes, M. Scanning tunneling spectroscopy at the single atom scale. Ph.D. thesis, EPFL (2006).

Brand, J. et al. Electron and Cooper-pair transport across a single magnetic molecule explored with a scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. B 97, 195429 (2018).

Farinacci, L. et al. Tuning the coupling of an individual magnetic impurity to a superconductor: quantum phase transition and transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 196803 (2018).

Malavolti, L. et al. Tunable spin-superconductor coupling of spin 1/2 vanadyl phthalocyanine molecules. Nano Lett. 18, 7955–7961 (2018).

Kezilebieke, S., Žitko, R., Dvorak, M., Ojanen, T. & Liljeroth, P. Observation of coexistence of Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states and spin-flip excitations. Nano Lett. 19, 4614–4619 (2019).

Anderson, P. W. Localized magnetic states in metals. Phys. Rev. 124, 41–53 (1961).

Yoshioka, T. & Ohashi, Y. Numerical renormalization group studies on single impurity Anderson model in superconductivity: a unified treatment of magnetic, nonmagnetic impurities, and resonance scattering. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 69, 1812–1823 (2000).

Vecino, E., Martín-Rodero, A. & Yeyati, A. L. Josephson current through a correlated quantum level: Andreev states and π junction behavior. Phys. Rev. B 68, 035105 (2003).

Martín-Rodero, A. & Yeyati, A. L. The Andreev states of a superconducting quantum dot: mean field versus exact numerical results. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24, 385303 (2012).

Dynes, R. C., Narayanamurti, V. & Garno, J. P. Direct measurement of quasiparticle-lifetime broadening in a strong-coupled superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41, 1509–1512 (1978).

Bauer, J., Pascual, J. I. & Franke, K. J. Microscopic resolution of the interplay of Kondo screening and superconducting pairing: Mn-phthalocyanine molecules adsorbed on superconducting Pb(111). Phys. Rev. B 87, 075125 (2013).

Cuevas, J. C. et al. Evolution of conducting channels in metallic atomic contacts under elastic deformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2990–2993 (1998).

Hatter, N., Heinrich, B. W., Ruby, M., Pascual, J. I. & Franke, K. J. Magnetic anisotropy in Shiba bound states across a quantum phase transition. Nat. Commun. 6, 8988 (2015).

Franke, K. J., Schulze, G. & Pascual, J. I. Competition of superconducting phenomena and Kondo screening at the nanoscale. Science 332, 940–944 (2011).

Ménard, G. C. et al. Coherent long-range magnetic bound states in a superconductor. Nat. Phys. 11, 1013–1016 (2015).

Yang, X. et al. Observation of short-range Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states with threefold symmetry in layered superconductor 2H-NbSe2. Nanoscale 12, 8174–8179 (2020).

Žitko, R. Quantum impurity models for magnetic adsorbates on superconductor surfaces. Physica B: Cond. Mat. 536, 230–234 (2018).

Pillet, J.-D. et al. Andreev bound states in supercurrent-carrying carbon nanotubes revealed. Nat. Phys. 6, 965–969 (2010).

Rodrigo, J. G., Suderow, H. & Vieira, S. On the use of STM superconducting tips at very low temperatures. Eur. Phys. J. B 40, 483–488 (2004).

Guillamon, I., Suderow, H., Vieira, S. & Rodiere, P. Scanning tunneling spectroscopy with superconducting tips of Al. Physica C: Supercond. Appl. 468, 537–542 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge stimulating discussions with A. Kadlecová, T. Novotný, M. Ternes, and R. Žitko. This work was funded in part by the ERC Consolidator Grant AbsoluteSpin (grant no. 681164) and by the Center for Integrated Quantum Science and Technology (IQST). J.A. acknowledges funding from the DFG under grant number AN336/11-1. A.L.Y. and J.C.C. acknowledge funding from the Spanish MINECO (grant no. FIS2017-84057-P and FIS2017-84860-R), from the “María de Maeztu” Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D (MDM-2014-0377).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. did the experiments with support from J.S., R.D., K.K., and C.R.A. C.R.A. provided the theory with support from C.P., A.L.Y., J.C.C., B.K., J.A., and H.H. H.H. and C.R.A. modeled and analyzed the data with support from all authors. All authors discussed the results. H.H. and C.R.A. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, H., Drost, R., Senkpiel, J. et al. Quantum phase transitions and the role of impurity-substrate hybridization in Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states. Commun Phys 3, 199 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00469-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00469-0

This article is cited by

-

Tracking a spin-polarized superconducting bound state across a quantum phase transition

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Microwave excitation of atomic scale superconducting bound states

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Universal scaling of tunable Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states across the quantum phase transition

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Spin-orbital Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states in single Kondo molecular magnet

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Superconducting quantum interference at the atomic scale

Nature Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.