Abstract

Study design:

Community cross-sectional self-report survey of adults with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to examine the likelihood of depression, anxiety and stress in adults with non-traumatic SCI (NT-SCI) compared with adults with traumatic SCI (T-SCI).

Setting:

Victoria, Australia. Adults (N=443; NT-SCI n=62) living in the community and attending specialist SCI rehabilitation clinics.

Methods:

Participants completed a self-report survey by internet, telephone or hard copy. Items included demographic and injury-related characteristics and the short form Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21).

Results:

Persons with NT-SCI were significantly more likely to be female (P<0.05), older (P<0.001) and have lower-level incomplete injuries (P<0.001). The probability of depression, anxiety or stress in respondents with NT-SCI did not differ from persons with T-SCI (P>0.05). Overall, the prevalence of adverse mental health problems defined by scoring above DASS-21 cutoffs, were depression 37%, anxiety 30%, and clinically significant stress 25%.

Conclusions:

This study examined multiple mental health outcomes after NT-SCI in Australia. This study provides some evidence that the results of studies of depression, anxiety or stress in persons with T-SCI can be generalised to those with NT-SCI in the post-acute phase. NT-SCI patients are also at substantial risk of poor mental health outcomes. General demographic and injury-related characteristics do not seem to be important factors associated with the mental health of adults with SCI whether the SCI is traumatic or non-traumatic in origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) can result in considerable disability. The highest risk of traumatic SCI (T-SCI) occurs during adolescence and early adulthood for both males and females with the ratio of males to females roughly four to one. Transport-related accidents are the most common cause of T-SCI.1 In contrast, the risk of non-traumatic SCI (NT-SCI) is higher in older adults with a more even gender ratio. In contrast to T-SCI, NT-SCI tends to be incomplete and more likely to result in paraplegia. The most common aetiologies of NT-SCI are tumours, degenerative conditions and vascular problems.2

Spinal cord injuries can have a significant adverse effect on mental health. There is a considerable but not inevitable risk of experiencing an emotional disorder such as depression after SCI.3 Emotional disorders after SCI have been associated with poorer outcomes such as increased pain.4

Compared with T-SCI, there have been relatively few studies investigating the mental health of adults with NT-SCI. A study that investigated the mental health of 89 adults with cervical spondylotic myelopathy, reported that 29% had significant depression and 38% had anxiety.5 Scivoletto, and colleagues found that the aetiology of the SCI had no effect on the levels of depression or anxiety in a sample of 100 adults who ranged 3 months to 28 years post-injury.6 Thirteen percent of those adults were depressed and 18% were anxious. Cook reported that the aetiology of the SCI had no bearing on levels of depression or anxiety among 118 adults with SCI who were <1 year post-injury.7

The above studies have limited ability to make clear any potentially significant factors that may be associated with an emotional disorder post NT-SCI. The number of adults with NT-SCI was small within the study by Scivoletto and colleagues6 and it is arguable whether Cook's investigation would be able to identify any significant associations given the small proportion of the sample experiencing adverse outcomes.7 The study by Stoffman and colleagues was limited to only one cause of NT-SCI.5

Migliorini, Tonge and Taleporos8 recently described the significantly increased risk of emotional disorders in adults with SCI living in the Australian community compared with the general population. New and Sandarajan's recent study reported that NT-SCI is more common than T-SCI.9 It is important for rehabilitation professionals to know of the risk of emotional disorders associated with NT-SCI in order to optimise patient care. The aim of this study was to examine the likelihood of depression, anxiety and stress in adults with NT-SCI compared with adults with T-SCI.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 443 adults with sudden-onset SCI who were 18 years and older and 6 months or more post-injury. Sixty-two (14%) had a NT-SCI which, if not immediate in onset, developed within 36 h. Participants were recruited during 2004 from the outpatient register of the only hospital in the state with an acute SCI unit that treats mainly T-SCI but also some patients with NT-SCI (Austin Hospital, Victoria, Australia). Participants were also sourced from the outpatient clinic of the only other hospital in Melbourne with a dedicated SCI rehabilitation unit that focuses on treating NT-SCI (Caulfield Hospital, Victoria, Australia). Participants could complete a survey on the web, by telephone or hard copy. The overall response rate was 44%: 61% hard copy, 23% web, 16% telephone interview. Individuals who completed the survey were not significantly different from non-completers in current age (P>0.05) or gender (P>0.05). Missing Value Analysis10 showed no systematic patterns in missing data.

Instruments

The survey included demographic and injury-related items and standardised scales. The independent variable Household Income was an item from the objective quality of life (QoL) Material subscale and Health was the objective QoL Health subscale. Both variables were from the Comprehensive Quality of Life Scale—Adult fifth version (COMQoL A5, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia). This scale is a psychometrically sound scale that is designed for use with any section of the adult population.11 The Cronbach α coefficient for Health was 0.497. When scales consist of <7 items, the mean inter-item correlation for the items rather than Cronbach α coefficients is recommended as a test of reliability. The subscale inter-item correlation of Health, ranging from 0.2 to 0.5, was satisfactory and near the recommended optimal range of 0.2–0.4.12

The short form of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) is a reliable and valid self-report scale that has been used successfully within general populations13 and populations with physical disabilities including SCI.14 The DASS-21 was used to differentiate between symptoms of depression, anxiety and clinical-level stress using the 0–3 point scoring system and clinical cut-offs validated by Henry and Crawford.15 Summed scores equal to and over five, four and eight are considered clinically significant for the depression, anxiety and stress scales, respectively. The Cronbach α coefficient for the overall DASS-21 scale was 0.927; α coefficients for the subscale domain depression was 0.902, for anxiety was 0.748, and for stress was 0.864. The terms depression, anxiety and stress will be used to indicate that the individual with SCI had a score above the published clinical cutoff. These terms are not synonymous with a clinical diagnosis but indicate a likelihood of such a diagnosis.

Analyses

Associations between traumatic and non-traumatic sample parameters were examined using χ2 and t-tests. Logistic regression analyses were used because of the expected positive skewing of the mental health outcomes, the categorical nature of some independent variables and the relatively small number of participants with NT-SCI. The binary outcomes were 0=normal non-clinical range of scores and 1=scores above the established clinical threshold for each subscale. All participants were included in the univariate parameter analyses but not the logistic regression analyses as there were no NT-SCI participants with complete tetraplegia. Standard logistic regression where all independent variables are entered simultaneously was used. Sequential analyses where some independent variables are assigned priority entry were not used as the a priori selection of independent variables may misrepresent the relative importance of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.16 Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for independent variables showing significant associations with the dependent variables in the logistic regression analyses, were calculated as follows:

Post hoc analyses were planned to test for potential biases that the method of survey completion may have created. DASS-21 items that represent physical sequela of emotional disorders (items 2, 4 and 19, for example, I was aware of dryness of my mouth), may also be confounded with the physical consequences of SCI or medications prescribed after SCI. Therefore, post hoc analyses that examined the relative contribution that the scores from the autonomic (physical) items had on the overall anxiety subscale scores were undertaken. The anxiety subscale was targeted as that subscale had the most autonomic items.

All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research. The research project was approved by Monash University and both participating hospitals Ethics Committees. Each participant gave informed consent. The surveys were strictly confidential but not anonymous. Each participant who was likely suffering emotional distress was approached and offered referral for psychological care.

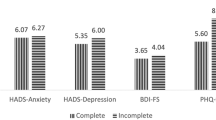

Results

The most common aetiology of SCI was T-SCI (86%). Tables 1 and 2 report the causes and frequency of T-SCI and NT-SCI conditions. In numerous cases, although respondents indicated that the cause of their SCI did not involve trauma, the exact aetiology was not able to be determined from the detail provided. Initial analyses showed statistically significant differences between respondents with T-SCI and NT-SCI. Those with NT-SCI were significantly more likely to be female, older, and have lower level incomplete injuries—Table 3. Overall, the prevalence of depression was 37%, anxiety was 30% and stress was 25%. Univariate analysis suggests there was no relationship between depression, anxiety or stress with the aetiology of SCI.

Table 4 shows the logistic regression model for each mental health outcome. These analyses confirm the univariate finding that aetiology of SCI is not associated with any of the mental health outcomes. No outliers were detected in the regression analyses. Health and Income were the only independent variables that had a significant association with each mental health outcome. Better health was associated with a reduction in the likelihood of depression by 23% (OR=0.82 (95% CI: 0.74–0.90)), anxiety by 27% (OR=0.79 (95% CI: 0.71–0.88)) and clinically significant stress by 33% (OR=0.75 (95% CI: 0.67–0.85)) for each unit increase in Health. Participants whose household income was below $26 000 had twice the likelihood of depression (OR=1.99 (95% CI: 1.10–3.58)), anxiety (OR=2.00 (95% CI: 1.06–3.76)) and stress (OR=1.96 (95% CI: 1.00–3.81)).

The likelihood of depression was also significantly associated with time since injury and gender. There was a 3% decrease in the likelihood of depression with every year post injury (OR=0.97 (95% CI: 0.95–0.99)) and females had twice the likelihood of depression (OR=2.00 (95% CI: 1.16–3.42)).

Age, level of injury and marital status were each associated with clinically significant stress. For each additional year of age, the likelihood of stress decreased by 2% (OR=0.98 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99)). Participants with complete paraplegia had a more than 2-fold reduction in the probability of stress compared with those with incomplete paraplegia or incomplete tetraplegia (OR=0.45 (95% CI: 0.24–0.86)). The likelihood of stress was significantly smaller for participants who were single (OR=0.42 (95% CI: 0.21–0.84)).

In the post hoc analyses, inclusion of the independent variable—Method of Survey Completion—into each of the regression analyses was not statistically significant. There were only minor changes to the coefficients and only the independent variable Income (<$26 000) became non-significant (P>0.05) in the regression where stress was the dependent variable. In the post hoc analyses of associations between autonomic items and those scoring above the anxiety subscale cutoff, each correlation was statistically significant (P<0.001). It was those within the non-anxious group however, that had the strongest association with the autonomic items. This suggested that the potential confounding was unlikely (Table 5.)

Discussion

In the present study, both univariate and multivariate analyses did not detect any significant association between the cause of SCI and the occurrence of depression, anxiety or stress. This was despite a significant divergence in demographic and injury-related features that characterised the adults with T-SCI and NT-SCI. The distribution of demographic2, 17 and injury-related characteristics2, 18 of the T-SCI and NT-SCI groups was consistent with earlier studies. This provides support for generalisations made from our results to other SCI populations. Notwithstanding the lack of relationship between the aetiology of SCI, and adverse mental health outcomes examined, other variables were associated with the dependent outcomes.

In the present study, health showed a statistically significant association with each of the mental health outcomes. Those with better health were substantially less likely to be experiencing depression, anxiety or stress. This is in accordance with the general understanding of mental health after SCI19 and concurs with those studies that included the aetiology of SCI within their study design.6, 7

In the present study, Household Income was the only other independent variable to be significantly associated with each of the mental health outcomes. Those individuals living within the lowest income bracket were substantially more likely to be experiencing depression, anxiety and stress. Neither Cook or Scivoletto and colleagues used income within their studies but other studies that examined mental health outcomes of individuals with T-SCI have also reported income to be associated with poorer mental health.20, 21 The association of low household income with an increased probability of poor mental health is also in keeping with general psychological understanding.22

In the present study, age was not associated with either depression or anxiety. In contrast, Cook found age to be significantly associated with depression but not anxiety.7 Cook found those who were older (aged 35–67 years) had higher depression scores than those who were younger (aged 15–34 years). In this study, being female increased the likelihood of depression only. In contrast, Scivoletto et al. found no relationship between gender, age or marital status with either depression or anxiety.6

Differences in study parameters may account for the disparity between earlier reports and the results of the present study. The sample size used in this study (N=443) was much larger than that used by Cook (N=118)7 and Scivoletto and colleagues (N=100).6 Cook found that only two individuals met the criteria for depression and the overall level of anxiety was less than for college students under stressful conditions. These issues limit the power of those studies to identify factors that may influence the likelihood of an emotional disorder according to aetiology of SCI. Other considerations that may also account for the divergence in results are the country of origin of the research—USA (Cook), Italy (Scivoletto et al.) and Australia for the present study; different eras when the studies were conducted—1970s (Cook), 1990s (Scivoletto et al.) and 2000s for the present study, and the different survey tools used in each study. Future studies are still necessary to extend our knowledge of risk of emotional disorders after NT-SCI.

In their review of depression after SCI, Elliot and Frank19 discussed the potential confound that the physical symptoms of SCI with the physical sequelae of mental disorders may introduce thereby artificially inflating the prevalence of an emotional disorder. An examination of the subscale with the most autonomic items—Anxiety—found that, rather than confounding the results, the autonomic items actually seemed to play a legitimate role indicating the presence of anxiety. This was congruent with the conclusion drawn by Bombardier and colleagues.3

In the present study, stress was envisaged as a negative mental health outcome that may warrant clinical intervention separate to depression and anxiety. The measure of stress used represents a tension-stress syndrome that is more than the tension or stress felt by most individuals during taxing times of life. Some incongruity in the results was observed in the regression analysis on stress. Respondents who were younger, single and with complete paraplegia were each substantially less associated with stress. On face value, this seems to counter earlier findings. For example, Rintala and colleagues found veterans with SCI who were younger when injured had higher perceived stress scores and that other demographic and injury-related characteristics were not related to perceived stress with the exception of using a respirator.23 These discrepancies may reflect overall differences in the sample populations. Rintala and colleagues sample were male veterans whilst the present study was of adults residing in the community. It is unclear whether the sample population used by Rintala and colleagues included anyone with NT-SCI. In addition, a reasonable proportion (31%) of the sample had tetraplegia (ASIA A, B or C), whereas in the present study there were not any adults with complete tetraplegia due to NT-SCI.

Limitations

The present study was a cross-sectional survey based on self-reports and not actual diagnoses. The DASS-21 however has evidenced good predictive properties.13, 14 The proportion of the sample with NT-SCI was relatively small (14%). Participants were recruited from more than one source and the sampling was not random. The overall characteristics of the sample seem similar to earlier epidemiological research1, 2 however it would be useful for future studies to include larger proportions of persons with NT-SCI.

There was a substantial proportion of variance unaccounted for within each of the logistic models (not reported). This suggests that important factors associated with mental health outcomes were not included in the analyses. Future research that includes other environmental, social and/or personal factors would be useful in examining factors that may be associated with the mental health outcomes of depression, anxiety and clinically significant stress in these patients. Future research into the mental health of adults with NT-SCI also needs to include the acute phase after injury and patients with more gradual onset of SCI.

The present study has provided some evidence that the results of studies of depression, anxiety and stress in persons with T-SCI more than 6 months post injury, can be generalised to persons with NT-SCI. Persons with NT-SCI are also at substantial risk of poor mental health outcomes. Furthermore, general demographic and injury-related characteristics do not seem important factors associated with mental health outcomes whatever the aetiology of the SCI.

References

O'Connor P . Incidence and patterns of spinal cord injury in Australia. Accid Anal Prev 2002; 34: 405–415.

New PW, Rawicki HB, Bailey MJ . Nontraumatic spinal cord injury: demographic characteristics and complications. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83: 996–1001.

Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Krause JS, Tulsky D, Tate DG . Symptoms of major depression in people with spinal cord injury: implications for screening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1749–1756.

Haythornthwaite JA, Benrud-Larson LM . Psychological aspects of neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain 2000; 16 (2 Suppl): S101–S105.

Stoffman MR, Roberts MS, King Jr JT . Cervical spondylotic myelopathy, depression, and anxiety: a cohort analysis of 89 patients. Neurosurgery 2005; 57: 307–313.

Scivoletto G, Petrelli A, Di Lucente L, Castellano V . Psychological investigation of spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 516–520.

Cook DW . Psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury: Incidence of denial, depression, and anxiety. Rehabil Psychol 1979; 26: 97–104.

Migliorini C, Tonge B, Taleporos G . Spinal cord injury and mental health. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008; 42: 309–314.

New P, Sandarajan V . Incidence of non-traumatic spinal cord injury in Victoria: a population-based study and literature review. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 406–411.

SPSS 15.0 for Windows. In. release 15.0.0 (6 Sep 2006): SPSS Inc, 2006.

Cummins RA . Comprehensive quality of life scale—adult (ComQol-A5), 5th edn. Deakin University: Melbourne, 1997. Available at www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/index.htm Accessed 8 September 2008.

Briggs SR, Cheek JM . The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J Pers 1986; 54: 106–148.

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF . Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd edn. The Psychology Foundation of Australia Inc.: Sydney, Australia, 1995. Available at http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/groups/dass/. Accessed 17 July 2008.

Mitchell MC, Burns NR, Dorstyn DS . Screening for depression and anxiety in spinal cord injury with DASS-21. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 547–551.

Henry JD, Crawford JR . The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005; 44: 227–239.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (eds). Using Multivariate Statistics. HarperCollins College Publishers: New York, NY, 1996.

Yeo JD, Walsh J, Soden R, Craven M, Middleton J . Mortality following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 329–336.

Cripps RA . Spinal cord injury, Australia, 2004–5. Injury Research and Statistics Series Number 29. AIHW (AIHW cat no. INJCAT86): Adelaide, 2006.

Elliott TR, Frank RG . Depression following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 816–823.

Krause JS, Kemp B, Coker J . Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 1099–1109.

Rintala DH, Robinson-Whelen S, Matamoros R . Subjective stress in male veterans with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005; 42: 291–304.

Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Slade T, Brownhill S, Andrews G . Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV major depression in an Australian national survey. J Affect Disord 2003; 75: 155–162.

Rintala DH, Robinson-Whelen S, Matamoros R . Subjective stress in male veterans with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005; 42: 291–304.

Acknowledgements

The Monash University Postgraduate Publications Award and the Robert Rose Foundation PhD Scholarship are thanked for their assistance in the form of research grants to Dr Migliorini. Some of the results reported here were presented at the Australian and New Zealand Spinal Cord Society 14th Annual Scientific Meeting, 1st–3rd November 2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Migliorini, C., New, P. & Tonge, B. Comparison of depression, anxiety and stress in persons with traumatic and non-traumatic post-acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 47, 783–788 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.43

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.43

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cognitive appraisals of disability in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury: a scoping review

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Body experience during post-acute rehabilitation in individuals after a traumatic spinal cord injury: a qualitative interview-based pilot study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2021)

-

The associations of acceptance with quality of life and mental health following spinal cord injury: a systematic review

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

A randomised control trial of an Internet-based cognitive behaviour treatment for mood disorder in adults with chronic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2016)

-

Anxiety prevalence following spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis

Spinal Cord (2016)