Abstract

Understanding the colonisation process in zooplankton is crucial for successful restoration of aquatic ecosystems. Here, we analyzed the clonal and genetic structure of the cyclical parthenogenetic rotifer Brachionus plicatilis by following populations established in new temporary ponds during the first three hydroperiods. Rotifer populations established rapidly after first flooding, although colonisation was ongoing throughout the study. Multilocus genotypes from 7 microsatellite loci suggested that most populations (10 of 14) were founded by few clones. The exception was one of the four populations that persisted throughout the studied hydroperiods, where high genetic diversity in the first hydroperiod suggested colonisation from a historical egg bank, and no increase in allelic diversity was detected with time. In contrast, in another of these four populations, we observed a progressive increase of allelic diversity. This population became less differentiated from the other populations suggesting effective gene flow soon after its foundation. Allelic diversity and richness remained low in the remaining two, more isolated, populations, suggesting little gene flow. Our results highlight the complexity of colonisation dynamics, with evidence for persistent founder effects in some ponds, but not in others, and with early immigration both from external source populations, and from residual, historical diapausing egg banks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding natural colonisation processes is crucial to the interpretation of species diversity patterns1, the prediction of the spread of alien species2,3,4 and the management of habitat restoration and community reestablishment. The interplay of evolutionary forces is especially intense during colonisation, with long lasting effects on the genetic structure of populations5,6. In continental aquatic habitats, zooplankton display high dispersal and colonisation abilities7,8,9, but genetic differentiation can be extensive even between neighbouring populations10,11. Persistent founder effects, resulting from colonisation from a few individuals and subsequent rapid growth rates and therefore a numerical advantage of the first colonists11,12,13, rapid genetic adaptation to local conditions14,15, and the build-up of large dormant egg banks16, can lead to monopolization of resources by genotypes descending from the initial founders10. De Meester et al.10 summarised these processes as the ‘Monopolization hypothesis’, which is especially relevant for cyclically parthenogenetic zooplankters, such as monogonont rotifers and cladocerans. In populations of the rotifer Brachionus and the waterflea Daphnia, persistent founder events result in low levels of gene flow between nearby ponds and in high genetic differentiation11,17. Several studies have emphasized the key role of monopolization in shaping the genetic structure of populations15,18.

However, it is currently unknown at what stage during the colonisation process monopolisation will become apparent. During the early stages of population establishment, monopolization by the first colonists may be counteracted by other factors favouring ongoing migration10. For example, newly established dormant egg banks may be relatively small and lack ecologically relevant variation, reducing their buffering role against immigrant genes 19,20. Inbreeding depression is also likely to occur, since colonising populations often descend from a few founder genotypes which will likely result in high selfing rates18. Additionally, in cyclical parthenogens, clonal selection throughout the growing season (when reproduction is parthenogenetic) could reduce the number of genotypes available for sexual reproduction, resulting in a low effective population size13,21. As a consequence, later immigrants with a strong fitness advantage could hybridize with inbred residents (outbreeding), making gene flow more effective and reducing monopolization effects. This has been shown for young Daphnia metapopulations, where outbred genotypes rapidly increase their frequency due to hybrid vigour (competitive advantage), leading to the incorporation of new alleles in subsequent generations19,22,23. Given the inbreeding depression and hybrid vigour found in the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis, opportunities for gene flow may occur in small, recently founded populations in which monopolization effects are not yet strong24.

The relative contribution and interaction of such evolutionary forces on the genetic makeup of colonising populations is currently much debated. In order to better understand the underlying processes, populations in newly colonised habitats must ideally be tracked over several years. However, evolutionary studies of colonisation in the wild are difficult and labour intensive, and very rarely have natural populations been tracked from the first stages of colonisation, partly due to the fleeting nature of the colonisation process on an ecological scale18,25,26. In this sense, newly created aquatic habitats offer a unique opportunity to investigate the dynamics of zooplankton colonisation and the interplay of evolutionary forces from the earliest stages of population foundation5,18,23. Zooplankton provide excellent models for a cost-effective evaluation of the colonisation success of new habitats, both from an ecological27,28 and a genetic23,29 perspective. Zooplankters that disperse passively via diapausing eggs (e.g. monogonont rotifers, cladocerans, calanoid copepods) can colonise habitats from a few propagules (as few as 1 to 3 in Daphnia9). Diapausing eggs reach new habitats through wind, water flow and animal-mediated transport30, and are able to cope with extreme environmental conditions and desiccation, forming extensive dormant egg banks, which remain viable for a long time in the sediments16,31.

In the present study, we took advantage of the construction of temporary ponds in a restored marshland in one of the most important European wetlands (Doñana National Park, SW Spain)32 to track the first stages of zooplankton colonisation. Ponds were arranged in two major blocks of 44 ponds each, plus eight isolated ponds in an estate of former farmland. We analysed the patterns of clonal diversity and genetic structure of newly established populations of the cyclical parthenogenetic rotifer Brachionus plicatilis, during the first three hydroperiods after pond construction. According to the Monopolisation hypothesis, and assuming an absence of historical egg banks due to either aging or pond excavation, we aimed at testing the following specific hypotheses: (i) new populations are founded by few diapausing eggs dispersing from external sources, resulting in low clonal richness and no linkage or HW equilibrium for the new populations in the first hydroperiod; (ii) limited or no increase of allelic diversity over subsequent hydroperiods would be observed when persistent strong founder effects prevent the successful establishment of immigrant genotypes; (iii) genetic drift should result in increasing population genetic differentiation with time.

Results

Brachionus plicatilis populations

Over the course of the three studied hydroperiods, the B. plicatilis species complex was found in 36 out of the 58 sampled new ponds and in one of eight reference sites in the surrounding area (Supplementary Table S1 for densities of the species complex over the study period in each pond). Of these 36 ponds, 17 were not studied further as rotifer densities were extremely low over the three hydroperiods (total accumulated density <5 ind·L−1). Four populations detected for the first time in the 3rd hydroperiod (4N3, 1S1, 4S3 and 7S3) were not analysed as these ponds had not been sampled in previous hydroperiods (see Supplementary Table S1).

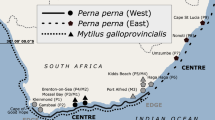

A total of 27 samples from the three hydroperiods with a high proportion of B. plicatilis sensu stricto individuals (B. plicatilis hereafter), according to positive species-specific Bp1b PCR amplification33, were selected for genetic analysis. These samples belonged to 14 new ponds: 9 within-block ponds and 5 isolated ponds (Fig. 1). No B. plicatilis was found in any of the reference sites (see Supplementary Table S1).

The subset of new ponds investigated is highlighted with a bold edge. Black filled ponds are those selected for the study of populations of B. plicatilis sensu stricto. Drainage ditches present prior to restoration are also shown (hatched straight lines). This map was produced with the online software ArcGIS (https://www.arcgis.com/).

Only four of the 14 ponds studied held B. plicatilis populations in all three hydroperiods: two ponds in the northern block, 3N3 and 6N2, and two isolated ponds, AC3 and AE6. Populations in ponds 0S1 and AE5 were only analysed in the 1st hydroperiod either because we could not detect them thereafter, or because their densities were too low for analysis (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1). Eight additional populations were analysed in the 3rd hydroperiod (ponds 0N2, 0S2, 0S3, 2S1, 6S2, 10S4, AC4 and AE7). In the 3rd hydroperiod, populations showed high densities and the species became widespread. We cannot exclude the presence of populations in the southern block of ponds during the 2nd hydroperiod since sampling was prevented during most of the hydroperiod (see Methods).

The name of the new pond to which each sample belongs is shown at the top and the bottom of the plot. Each shade in the stacked bars represents a different clone, but the same shade does not represent the same clone in different samples. The total number of clones found in each sample is given above each stack bar.

Allelic richness

Six loci were polymorphic in the populations studied with 6 alleles in Bp1b, 6 alleles in Bp2, 5 alleles in Bp3c, 14 alleles in Bp4a, 4 alleles in Bp5d and 3 alleles in Bp6b, which were used to construct the multi-locus genotype (MLG, also see next section) for each individual. Despite previous successful amplification in a control population (Torreblanca Marsh, Spain)13, locus Bp3 could not be used in our populations due to inconsistent amplification. Due to the low (0.012 overall) frequency of null alleles across microsatellite loci and populations, correction for null alleles was not performed. The least polymorphic locus Bp6b was fixed in 14 of the 27 samples for one allele, which in the remaining samples showed a frequency ≥67%. Private alleles were found only in the most polymorphic locus Bp4a: (one allele in 6N2, one in 3N3, and one in 10S4 with frequencies of 0.028, 0.010 and 0.012, respectively). The number of polymorphic loci per sample ranged from 3 to 6, and the total number of alleles per sample from 11 to 30. The allelic richness per sample, averaged over loci and adjusted for the minimum sample size (41 individuals), ranged from 1.50 to 4.85 (Table 1). No linkage disequilibrium was found for any of the studied loci in the analysed samples. Figure 3 depicts the temporal patterns in all three hydroperiods of the genetic parameters observed in the new ponds with B. plicatilis populations (i.e. (A) inbreeding coefficient (FIS), (B) allelic richness, and (C) average pairwise genetic differentiation (Dest)).

(A) inbreeding coefficient (FIS), (B) allelic richness adjusted for minimum sample size, and (C) average pairwise genetic differentiation (Dest) among each pond and the others within each hydroperiod. (*) Indicates Fis values significantly different from zero. Note the y axis is not to scale. Vertical dotted lines separate hydroperiods.

Of the four populations that were present throughout the study period, the number of alleles and allelic richness was highest in population 3N3 and remained stable in all three hydroperiods (29 to 31 alleles, Table 1, Fig. 3B). In population 6N2, the number of alleles increased from 9 (in the single founding clone) to 26 in the 3rd hydroperiod, with its allelic richness increasing from 1.50 to 4.07 (Fig. 3B) indicating successful immigration of new clones (Table 1, see Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, in the two isolated populations, the number of alleles and allelic richness either increased only slightly through time (AC3, 14 to 16 alleles) or remained stable (AE6, 13 alleles)(Table 1).

Multilocus genotypes and HWE

The number of MLGs per sample per hydroperiod ranged from 1 to 102 (Fig. 2 and Table 1). All B. plicatilis populations from the 1st hydroperiod, except 3N3, had a low number of MLGs (<12), which could be regarded as an accurate estimate of the number of clones according to GenClone 2.0 (see Methods). In the most extreme case, all individuals of population 6N2 (N = 63) shared the same MLG, and thus this was considered a monoclonal population in the 1st hydroperiod (Fig. 2). In the course of the study period, the number of clones and clonal diversity increased in this population. Five of the populations detected for the first time in the 3rd hydroperiod also had a low number of MLGs (<10) and low clonal diversities (Table 1), suggesting recent colonisation and population establishment.

Significant heterozygote excess (negative FIS, Table 1) was common in ponds with low clonal diversity in their first hydroperiod, an indication that the few heterozygous individuals that colonised the ponds proceeded to reproduce parthenogenetically. Both isolated populations, AC3 and AE6, had a significant excess of heterozygotes (positive FIS, Table 1) during almost the entire study period, and their clonal diversity decreased in the 3rd hydroperiod (Table 1). In contrast to the other three populations detected throughout the three hydroperiods, we observed high clonal diversity and genetic stability across hydroperiods in population 3N3 (Figs 1 and 4).

Patterns of HWE differed among the four populations detected throughout the three hydroperiods (Table 1): populations 6N2, AC3 and AE6 departed from HWE in at least one of the studied hydroperiods due to heterozygote excess (Table 1), while population 3N3 was in HWE in all three hydroperiods.

Patterns of genetic differentiation

When considering all populations studied within each of the three hydroperiods, the overall genetic differentiation was very similar in each hydroperiod. It increased slightly from Dest = 0.161 (p = 0.001) in the 1st hydroperiod to Dest = 0.183 in the 2nd (p = 0.001) and it decreased to Dest = 0.150 (p = 0.001) in the 3rd (Fig. 4). A spatial pattern of genetic differentiation among ponds was also observed in the 3rd hydroperiod (Fig. 5; Mantel test, R = 0.292, p = 0.014, 9999 permutations).

The four populations that persisted throughout all three hydroperiods became more similar through time, converging on the highly diverse 3N3. The decrease in the average pairwise genetic differentiation observed between the 2nd and 3rd hydroperiod (Fig. 3C) was mainly driven by populations in which allelic diversity increased (6N2 and AC3), eventually becoming more similar to 3N3 (see NMDS plot in Fig. 4), which suggest the latter as a source population. In between the isolated populations, genetic differentiation was always higher than in the within-block populations. AMOVA results regarding these four populations (see Supplementary Table S2) indicate non-significant, low genetic differentiation among them in the 1st hydroperiod (FST = 0.019, p = 0.23). Although differentiation increased and became significant in the 2nd hydroperiod (FST = 0.14, p < 0.01), it decreased again in the 3rd hydroperiod (FST = 0.07, p < 0.01).

Discussion

The understanding of the early stages of habitat colonization is essential for a successful restoration of aquatic ecosystems. The construction of new, temporary ponds as part of a marshland restoration project, together with the high dispersal ability of rotifers34,35 offered a unique opportunity to study early zooplankton colonisation patterns. We explored the genetic diversity and structure of newly established Brachionus plicatilis populations throughout the first three hydroperiods of a subset of these ponds. Our results did not indicate a uniform colonisation pattern among the populations, highlighting the complexity of the colonisation process during these initial stages, with evidence for persistent founder effects in some populations, but also successful migration and subsequent homogenisation in other populations.

Over 60% of the new ponds monitored were colonised by the B. plicatilis species complex, which rapidly established large populations within three years of pond construction. Six out of the 14 populations analysed were detected during the 1st hydroperiod and attained considerable densities within weeks of the first flooding. Five populations were first detected in the 3rd hydroperiod, indicating that additional ponds continued to be colonised throughout the study period.

In support of the first hypothesis, we found that five of the six populations detected in the 1st hydroperiod had low values of genetic and clonal diversity of one to 11 clones (Table 1), indicating their recent founding by a small number of propagules, as observed in Daphnia populations17,18. In contrast, the high clonal diversity of the sixth population (3N3) and the presence of HW equilibrium suggest colonisation from a pre-existing egg bank which may have persisted from historic water bodies present in the marsh prior to the farmland conversion (see Methods). Zooplankton egg banks are important reservoirs of biological and genetic diversity16,36,37 that can maintain viable eggs during decades (60–80 years in Brachionus plicatilis38) or even centuries (e.g. ~700 yr in Daphnia39; >300 yr in calanoid copepods40). During pond construction, former agricultural drainage ditches were filled with topsoil from the surrounding area, where diapausing propagules may have persisted. Although a previous study suggested low densities of any remaining historical egg banks41, the fact that pond 3N3 partly overlay one of these ditches could explain the observed genetic pattern. In contrast, the high genetic diversity of some populations first detected in the 3rd hydroperiod is more difficult to explain. We may have failed to detect these populations in previous hydroperiods because abundance was below our detection limit or because the area where these ponds were located (southern block) was inaccessible for sampling due to flooding. All these ponds became part of a larger flooded area connecting several ponds in which B. plicatilis may have been present but that were not sampled (see Methods).

Given that B. plicatilis sensu stricto was not recorded in any of the reference sites, the sources of colonists for populations founded by a small number of clones remain uncertain. However, the lack of significant genetic structure at the onset of colonisation (AMOVA results, see Supplementary Table S2), suggests that ponds were colonised by a closely related subset of clones. Doñana is a large wetland complex containing highly diverse water bodies42 and the species complex of B. plicatilis has been widely recorded in the area and in other Andalusian wetlands43,44, including populations of B. plicatilis sensu stricto45. Moreover, previous results from a community ecology study in the same restored marshland35 do not support dispersal limitation for rotifers at such small spatial and short time scales.

We did not find clear evidence in favour or against persistent founder effects as patterns were not consistent with either. A significant population structure from the early colonisation stages due to chance events may be expected, especially if clonal diversity of source populations is high (i.e. as every pond would be colonised by a different set of clones). When persistent founder effects are present, an increase in genetic differentiation between populations over time can be expected12. In contrast, in our study no significant genetic structure was found at the onset of colonisation and although differentiation between all studied populations increased in the second hydroperiod, it dropped again to a much lower value in the third hydroperiod (AMOVA results, see Supplementary Table S2). Importantly, this pattern was also observed in the four populations present throughout the study, suggesting that it was unaffected by new populations established in the 2nd and 3rd hydroperiod.

The decrease in genetic differentiation observed in the 3rd hydroperiod was driven by two adjacent populations (3N3 and 6N2), suggesting gene flow. The absence of persistent founder effects in recently founded populations, like 6N2, may result from a small egg bank with little buffering capacity against migration. The size of the egg banks produced during the early stages of colonisation is likely to be smaller than those of mature habitats, and may have made a limited contribution to population dynamics20. We did not expect founder effects in 3N3 since this pond was presumably re-established from a pre-existing large egg bank of a historical, mature population with a high genetic and clonal diversity.

The four populations followed throughout three hydroperiods presented diverse patterns: the population presumably re-established from a historical egg bank (3N3) showed high and stable allelic and clonal diversity throughout the study. In the two spatially isolated ponds (AC3 and AE6), which were never connected to other ponds by flooding, allelic diversity was low and increased only slightly over time. The clonal diversity in these ponds increased exclusively by recombination during the sexual phase, given the absence of new alleles (Appendix 3). The significant spatial pattern found in the 3rd hydroperiod may suggest low immigration rates in the isolated populations compared to those in within-block ponds. If the number of immigrant genes is limited, and they do not disappear by drift, their frequencies in populations are expected to be low and to increase very slowly29, taking longer to be detected. Apart from low immigration rates, the observed pattern of stable, low allelic richness could be caused either by persistent founder effects, or by a combination of both. Finally, in the population that initially had a single-clone (6N2) we found a steady increase of allelic richness throughout the study period. This population is located at a short distance from the large, genetically diverse 3N3 population within the northern block and higher dispersal rates could be expected. Heterosis, and spread of immigrant genes within the inbred population18,19,26,46, may also have contributed to the increase in genetic diversity observed in this pond.

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was established after the 1st hydroperiod in population 6N2 that showed a continuous increase of allelic richness and clonal diversity. This population was founded by only one clone, presumably resulting in selfing for the production of dormant eggs at the end of the 1st hydroperiod. This population is likely to have suffered from strong inbreeding depression at the onset of the 2nd hydroperiod, providing a competitive advantage to immigrant genotypes, as observed in Daphnia metapopulations19,22,23. In contrast, the isolated populations AC3 and AE6 with stable allelic diversity showed evidence of heterozygote excess maintained over time. This could be due to colonisation by a few heterozygous individuals in the 1st hydroperiod, and strong selection for heterozygous individuals during the following hydroperiods17,47.

Conclusions

Overall, our study, although admittedly based on a small number of ponds, revealed that the colonisation of a cyclical parthenogenetic rotifer in newly created habitats was subject to a high level of stochasticity, at least during the early stages of the process. Founder effects were not expected in the population re-established from pre-existing egg banks, but were not apparent in the pond founded by a single clone, which showed that immigration might be important when bottlenecks are very strong. Even in those populations founded by few genotypes, the persistent founder effects were difficult to detect. Spatial isolation of these ponds may mask the founder effects, lowering the immigration rates in comparison to the ponds located within blocks. Whether persistent founder effects may establish during later years remains to be tested, similar to a study by Ortells et al.23 regarding Daphnia colonisation. Our results suggested that most of the colonising propagules came from external sources, but they also highlight the role of historical egg banks, as a local “genetic archive”, in facilitating re-colonisation and the build-up of new populations in restored habitats16.

Methods

Study species

Brachionus plicatilis sensu stricto is a cosmopolitan rotifer that inhabits salt lakes and brackish coastal lagoons11. It belongs to a cryptic species complex, with six species present in the Iberian Peninsula, which can only be reliably identified by molecular markers and can co-occur in the same habitat48,49. The species reproduces by cyclical parthenogenesis: the life cycle begins with the hatching of a sexually-produced, genetically unique diapausing egg in response to hatching cues. Massive hatching is thought to occur more or less synchronously in a population, mainly in the early stages of pond refilling, allowing this species to quickly reach high densities in the habitat. Hatchlings are diploid, parthenogenetic (amictic) females that produce genetically identical offspring (clones). Parthenogenetic or clonal reproduction occurs for an indefinite number of generations as long as conditions are favourable (parthenogenetic phase). Sexual reproduction takes place when external stimuli (e.g. population density, photoperiod) induce some females to produce sexual (mictic) daughters, which produce haploid sexual eggs. If unfertilized, these eggs develop to haploid males; otherwise they produce diploid diapausing eggs that accumulate in the sediment until external stimuli (e.g. light and oxygen) induce hatching.

Study site

The studied ponds are located within Caracoles estate, in Doñana National Park (SW Spain, Fig. 1), a former seasonally flooded marshland area of 27 Km2 turned into arable farmland in the 1960 s after drainage. Between summer 2004 and spring 2005, 96 experimental ponds were dug in the estate as part of a restoration project, ‘The Doñana 2005 restoration plan’50. Ponds were arranged in two major blocks of 44 pools each, plus eight spatially isolated ponds distributed throughout the estate. Some of them partly overlay former drainage ditches previously filled with topsoil from surrounding areas (Fig. 1). The ponds fill primarily by rainfall and local surface run-off and are frequented by a diverse waterbird community32. During and after major rainfall events, some ponds temporarily overflow and connect to flooded grassland areas and/or to neighbouring ponds. All ponds dry out completely during the summer, even in the wettest years.

Sample collection

A subset of initially 48 new ponds representative in terms of size, depth and connectivity was selected for sampling, including ponds from both major blocks and isolated ponds (Fig. 1). Eight nearby natural and semi-natural temporary water bodies, where B. plicatilis species complex had been previously detected34,44, were selected as reference sites (source populations) to be sampled simultaneously (for details see refs 34,35). Sampling was carried out bimonthly during the first three hydroperiods (occasionally monthly for some ponds; see Supplementary Table S1). In the last hydroperiod, 10 additional ponds were included in the study making a total of 58 new ponds.

The autumn/winter following pond construction was exceptionally dry, and the first flooding event for all new ponds occurred in January 2006. The duration of the first hydroperiod varied among ponds, with some beginning to dry out in early May and others persisting until late June 2006. In the 2nd hydroperiod that started in late October 2006, the first ponds dried out in early May and some persisted until July 2007. During the wettest period, in winter 2007, the southern block of ponds was inaccessible due to flooding of access routes. The 3rd hydroperiod started in December 2007 and lasted until late June 2008. This was the driest hydroperiod and only a small number of ponds, mainly in the northern block, could be sampled (see Supplementary Table S1).

Two zooplankton samples were collected during each pond visit: one for taxonomic identification and counting (preserved in 70% ethanol or lugol), and another for genetic analysis (preserved in absolute ethanol). No genetic samples were available in May 2006. Samples were kept in the dark at 4 °C until DNA was extracted. Each sample was obtained by filtering a minimum of 20 L of water through a 64 μm net. To avoid dispersing zooplankton and sediment transfer among ponds, the sampling equipment was rinsed with tap water and 70% ethanol between ponds, and boots were covered with plastic bags (see ref. 34 for details on zooplankton sampling and processing).

Microsatellite genotyping and analyses

For samples containing individuals of the Brachionus plicatilis species complex, we used positive amplification of the species-specific Bp1b microsatellite locus33 to identify individuals of B. plicatilis sensu stricto. For this purpose, a total of 916 individuals (minimum sample size of 19) were screened (see Supplementary Table S1). DNA was extracted from individual females using a modified HotSHOT protocol51, with a volume of 25–25 μL for lysis and neutralization solutions. PCR amplifications were performed in a reaction volume of 10 μL containing 2 μL of template DNA, 1 × NH4 PCR buffer (BIOLINE), 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.025 U of Taq DNA polymerase (BIOLINE). PCR reactions were performed in a Veriti® Fast Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems) as described in ref. 33. Three μl of the PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel in 1x TBE buffer and stained with ethidium bromide for band visualization. For logistic reasons, only those samples with a large proportion of B. plicatilis individuals were selected for further study.

Between 41 and 66 individuals per sample (depending on availability) were genotyped for seven trinucleotide microsatellite loci (Bp1b, Bp2, Bp3, Bp3c, Bp4a, Bp5d, Bp6b)33. All loci were amplified in a single multiplex PCR following a protocol optimized for the present study. Multiplex PCRs were performed in a reaction volume of 10 μL containing 2 μL of template DNA, 5 μL of 2x QIAGEN® Multiplex PCR Master Mix (including 3 mM MgCl2, dNTP Mix and HotStarTaq® Polymerase) and 2 μL of RNAse-free water. Each reverse primer was labelled in 5′ with a fluorescent dye (Cy5, Cy5.5, MWG Biotech; WellRED D2-PA, Sigma-Aldrich) for their detection in capillary electrophoresis. Primer concentration was optimized to improve amplification performance given the different strength of the fluorescent dyes to 0.1 μM for the Cy5-labelled Bp4a and Bp6b, 0.2 μM for the Cy5.5-labelled Bp2, Bp3c and Bp5d, 0.3 μM for D2-PA-labelled Bp1b and 0.4 μM for Cy5-Bp3. The multiplex PCR programme used was following QIAGEN recommendations. Diluted PCR products (1:20) were combined with a 400 bp-size standard and separated on a Beckman-Coulter CEQTM 8000. Alleles were scored using the CEQ Fragment Analysis software (Beckman-CoulterTM) and then checked manually.

A multi-locus genotype (MLG) was constructed for each individual based on its genotype at each individual locus to infer the clonal structure of the populations21. Within each sample, those individuals with the same MLG are likely to belong to the same clone (i.e. offspring of a genetically unique female). The program GenClone 2.052 was used to test if the number of loci and the sample size used were sufficient to accurately estimate the number of clones present in each sample, or otherwise, whether it should be considered an underestimate. A measure of clonal diversity (D*, Simpson complement), which combines richness and evenness52 was also obtained using this program.

The frequency of null alleles and pairwise FST values were calculated with FreeNA53. Other parameters of genetic diversity such as the number of polymorphic loci (PL), the total number of alleles (A) and the average expected heterozygosity at Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (He) were obtained using GenAlEx 6.454. FSTAT 2.9.355 was used to estimate allelic richness (Rs), as the average number of alleles per locus adjusted for the minimum sample size (41 individuals), using a rarefaction method56, as well as the inbreeding coefficient (Fis) over loci within each population testing for significant deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (based on 2880 randomizations). Linkage disequilibrium tests between all pairs of loci (based on 7200 permutations) were also calculated.

To test for temporal changes in the amount of genetic variance between and among populations, we performed analyses of molecular variance (AMOVA) based on FST in each hydroperiod separately, using GenAlEx 6.454. We performed AMOVA on a subset of data that contained only the populations analyzed throughout three hydroperiods, using only one individual per MLG to avoid the bias introduced by clonal reproduction. Genetic differentiation between populations was estimated using the unbiased differentiation statistic Dest57. The R-package DEMEtics58 was used to calculate Dest values, 95% confidence intervals and p-values (null hypothesis of zero differentiation) by means of 1000 bootstrapping iterations. All p-values were adjusted using Bonferroni correction for multiple tests. Pairwise measures of Dest were used as a distance matrix in a nonmetric multidimensional scaling ordination (NMDS) to provide a visual representation of the genetic variability among populations. Isolation by distance was assessed by Mantel test (9999 permutations), testing for relationships between genetic and geographic distances.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Badosa, A. et al. Isolation mediates persistent founder effects on zooplankton colonization in new temporary ponds. Sci. Rep. 7, 43983; doi: 10.1038/srep43983 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Seymour, M. & Altermatt, F. Active colonization dynamics and diversity patterns are influenced by dendritic network connectivity and species interactions. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1243–1254 (2014).

Abdelkrim, J., Pascal, M., Calmet, C. & Samadi, S. Importance of Assessing Population Genetic Structure before Eradication of Invasive Species: Examples from Insular Norway Rat Populations. Conserv. Biol. 19, 1509–1518 (2005).

Arim, M., Abades, S. R., Neill, P. E., Lima, M. & Marquet, P. A. Spread dynamics of invasive species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 374–378 (2006).

Drake, J. M. Heterosis, the catapult effect and establishment success of a colonizing bird. Biol. Lett. 2, 304–307 (2006).

Ortells, R., Vanoverbeke, J., Louette, G. & De Meester, L. Colonization of Daphnia magna in a newly created pond: founder effects and secondary immigrants. Hydrobiologia 723(1), 167–179 (2014).

Shirk, R. Y., Hamrick, J. L., Zhang, C. & Qiang, S. Patterns of genetic diversity reveal multiple introductions and recurrent founder effects during range expansion in invasive populations of Geranium carolinianum (Geraniaceae). Heredity 112, 497–507 (2014).

Jenkins, D. G. Dispersal-limited zooplankton distribution and community composition in new ponds. Hydrobiologia 313–314, 15–20 (1995).

Havel, J. E., Colbourne, J. K. & Hebert, P. D. N. Reconstructing the history of intercontinental dispersal in Daphnia lumholtzi by use of genetic markers. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 1414–1419 (2000).

Louette, G. & Meester, L. D. High dispersal capacity of cladoceran zooplankton in newly formed communities. Ecology 86, 353–359 (2005).

De Meester, L., Gómez, Africa, Okamura, B. & Schwenk, K. The Monopolization Hypothesis and the dispersal–gene flow paradox in aquatic organisms. Acta Oecologica 23, 121–135 (2002).

Gómez, A., Adcock, G. J., Lunt, D. H. & Carvalho, G. R. The interplay between colonization history and gene flow in passively dispersing zooplankton: microsatellite analysis of rotifer resting egg banks. J. Evol. Biol. 15, 158–171 (2002).

Boileau, M. G., Hebert, P. D. N. & Schwartz, S. S. Non-equilibrium gene frequency divergence: persistent founder effects in natural populations. J. Evol. Biol. 5, 25–39 (1992).

Gómez, A. & Carvalho, G. R. Sex, parthenogenesis and genetic structure of rotifers: microsatellite analysis of contemporary and resting egg bank populations. Mol. Ecol. 9, 203–214 (2000).

Cousyn, C. et al. Rapid, local adaptation of zooplankton behavior to changes in predation pressure in the absence of neutral genetic changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98, 6256–6260 (2001).

Orsini, L., Mergeay, J., Vanoverbeke, J. & De Meester, L. The role of selection in driving landscape genomic structure of the waterflea Daphnia magna . Mol. Ecol. 22, 583–601 (2013).

Brendonck, L. & De Meester, L. Egg banks in freshwater zooplankton: evolutionary and ecological archives in the sediment. Hydrobiologia 491, 65–84 (2003).

Haag, C. R., Riek, M., Hottinger, J. W., Pajunen, V. I. & Ebert, D. Founder events as determinants of within-island and among-island genetic structure of Daphnia metapopulations. Heredity 96, 150–158 (2006).

Louette, G., Gerald, L., Joost, V., Raquel, O. & De Meester, L. The founding mothers: the genetic structure of newly established Daphnia populations. Oikos 116, 728–741 (2007).

Ebert, D. et al. A selective advantage to immigrant genes in a Daphnia metapopulation. Science 295, 485–488 (2002).

Vandekerkhove, J., Louette, G., Brendonck, L. & De Meester, L. Development of cladoceran egg banks in new and isolated pools. Archiv für Hydrobiologie 162, 339–347 (2005).

De Meester, L., Vanoverbeke, J., De Gelas, K., Ortells, R. & Spaak, P. Genetic structure of cyclic parthenogenetic zooplankton populations – a conceptual framework. Archiv für Hydrobiologie 167, 217–244 (2006).

Haag, C. R., Hottinger, J. W., Riek, M. & Ebert, D. Strong inbreeding depression in a Daphnia metapopulation. Evolution 56, 518–526 (2002).

Ortells, R., Olmo, C. & Armengol, X. Colonization in action: genetic characteristics of Daphnia magna Strauss (Crustacea, Anomopoda) in two recently restored ponds. Hydrobiologia 689, 37–49 (2012).

Tortajada, A. M., Carmona, M. J. & Serra, M. Does haplodiploidy purge inbreeding depression in rotifer populations? PLoS One 4, e8195 (2009).

Grant, P. R., Grant, B. R. & Petren, K. A population founded by a single pair of individuals: establishment, expansion, and evolution. Genetica 112–113, 359–382 (2001).

Vilà, C. et al. Rescue of a severely bottlenecked wolf (Canis lupus) population by a single immigrant. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270, 91–97 (2003).

Cáceres, C. E. & Soluk, D. A. Blowing in the wind: a field test of overland dispersal and colonization by aquatic invertebrates. Oecologia 131, 402–408 (2002).

Cohen, G. M. & Shurin, J. B. Scale‐dependence and mechanisms of dispersal in freshwater zooplankton. Oikos 103, 603–617 (2003).

Haag, C. R., Riek, M., Hottinger, J. W., Pajunen, V. I. & Ebert, D. Genetic diversity and genetic differentiation in Daphnia metapopulations with subpopulations of known age. Genetics 170, 1809–1820 (2005).

Green, A. J. & Figuerola, J. Recent advances in the study of long-distance dispersal of aquatic invertebrates via birds. Divers. Distrib. 11, 149–156 (2005).

Mergeay, J., Vanoverbeke, J., Verschuren, D. & De Meester, L. Extinction, recolonization, and dispersal through time in a planktonic crustacean. Ecology 88, 3032–3043 (2007).

Sebastián-González, E. & Green, A. J. Habitat use by waterbirds in relation to pond size, water depth, and isolation: lessons from a restoration in southern Spain. Restor. Ecol. 22, 311–318 (2014).

Gómez, A., Clabby, C. & Carvalho, G. R. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in a cyclically parthenogenetic rotifer, Brachionus plicatilis . Mol. Ecol. 7, 1619–1621 (1998).

Badosa, A., Frisch, D., Arechederra, A., Serrano, L. & Green, A. J. Recovery of zooplankton diversity in a restored Mediterranean temporary marsh in Doñana National Park (SW Spain). Hydrobiologia 654, 67–82 (2010).

Frisch, D., Cottenie, K., Badosa, A. & Green, A. J. Strong spatial influence on colonization rates in a pioneer zooplankton metacommunity. PLoS One 7, e40205 (2012).

Hairston, N. G. Zooplankton egg banks as biotic reservoirs in changing environments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41, 1087–1092 (1996).

Latta, L. C., Fisk, D. L., Knapp, R. A. & Pfrender, M. E. Genetic resilience of Daphnia populations following experimental removal of introduced fish. Conserv. Genet. 11, 1737–1745 (2010).

García-Roger, E. M., Carmona, M. J. & Serra, M. Hatching and viability of rotifer diapausing eggs collected from pond sediments. Freshw. Biol. 51, 1351–1358 (2006).

Cáceres, C. E. Interspecific Variation in the Abundance, Production, and Emergence of Daphnia Diapausing Eggs. Ecology 79, 1699–1710 (1998).

Hairston, N. G., Van Brunt, R. A., Kearns, C. M. & Engstrom, D. R. Age and Survivorship of Diapausing Eggs in a Sediment Egg Bank. Ecology 76, 1706–1711 (1995).

Frisch, D. & Green, A. J. Copepods come in first: rapid colonization of new temporary ponds. Fundamental and Applied Limnology/Archiv für Hydrobiologie 168, 289–297 (2007).

Serrano, L. et al. The aquatic systems of Doñana (SW Spain): watersheds and frontiers. Limnetica 25, 11–32 (2006).

Serrano, L., Reina, M., Toja Santillana, J. & Casco, M. A. Limnological description of the Tarelo lagoon (SW Spain). Limnetica 23(1-2), 1–10 (2004).

Frisch, D., Arechederra, A. & Green, A. J. Recolonisation potential of zooplankton propagule banks in natural and agriculturally modified sections of a semiarid temporary stream (Doñana, Southwest Spain). Hydrobiologia 624, 115–123 (2008).

Gómez, A., Carvalho, G. R. & Lunt, D. H. Phylogeography and regional endemism of a passively dispersing zooplankter: mitochondrial DNA variation in rotifer resting egg banks. Proc. Biol. Sci. 267, 2189–2197 (2000).

Saccheri, I. J. & Brakefield, P. M. Rapid spread of immigrant genomes into inbred populations. Proc. Biol. Sci. 269, 1073–1078 (2002).

Haag, C. R. & Ebert, D. Genotypic selection in Daphnia populations consisting of inbred sibships. J. Evol. Biol. 20, 881–891 (2007).

Gómez, A. Molecular Ecology of Rotifers: From Population Differentiation to Speciation. Hydrobiologia 546, 83–99 (2005).

Mills, S. et al. Fifteen species in one: deciphering the Brachionus plicatilis species complex (Rotifera, Monogononta) through DNA taxonomy. Hydrobiologia 1–20, doi: 10.1007/s10750-016-2725-7 (2016).

Santamaria, L., Green, A. J., Diaz-Delgado, R., Bravo, M. & Castellanos, E. In Doñana: Water and Biosphere (ed. F. García-Novo & C. Marín) 325–327 (Guadalquivir Hydrologic Basin Authority, Spanish Ministry of Environment, 2006).

Montero-Pau, J., Munoz, J. & Gómez, A. Application of an inexpensive and high-throughput genomic DNA extraction method for the molecular ecology of zooplanktonic diapausing eggs. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 6, 218–222 (2008).

Arnaud-Haond, S. & Belkhir, K. GENCLONE: a computer program to analyse genotypic data, test for clonality and describe spatial clonal organization. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 15–17 (2007).

Chapuis, M.-P. & Estoup, A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 621–631 (2007).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539 (2012).

Goudet, J. FSTAT version 2.9. 3.2, a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices. http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm (2002).

El Mousadik, A. & Petit, R. J. High level of genetic differentiation for allelic richness among populations of the argan tree [Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels] endemic to Morocco. Theor. Appl. Genet. 92, 832–839 (1996).

Jost, L. GST and its relatives do not measure differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 17, 4015–4026 (2008).

Gerlach, G., Jueterbock, A., Kraemer, P., Deppermann, J. & Harmand, P. Calculations of population differentiation based on GST and D: forget GST but not all of statistics! Mol. Ecol. 19, 3845–3852 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank Arantza Arechederra, Sarah Rousseaux, Raquel Ortells, Pieter Vanormelingen, María Sahuquillo, María José Villena, Ernesto García, and Raquel López for fieldwork assistance. Thanks also to Arantza Arechederra, Mayca Lozano, Joaquín Muñoz and the Evolutionary Biology Group in the University of Hull (UK) for laboratory assistance. Fernando Pacios prepared the map of the study area. This research was funded by: Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa, Junta de Andalucía (Grant P06-RNM-02431 to AJG, DF and CR); Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Gobierno de España (‘Doñana 2005’. restoration project), and the European Science Foundation Eurodiversity programme (BIOPOOL). A.G. was funded by an Advanced NERC fellowship (NE/B501298/1). A.B.’s stay in the University of Hull was financed by a Grant from the Junta de Andalucía (Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa, IAC09-II-5510). The authors are also thankful to two anonymous referees for their constructive criticism on previous versions of this work and to the Editorial Board Member for handling the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.F. and A.J.G. conceived the study with input from C.R. on the genetic component. A.B. collected the samples; A.B., A.G. performed the microsatellite genotyping and A.B., A.G. and D.F. analyzed the data and wrote the paper with contributions from all five authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Badosa, A., Frisch, D., Green, A. et al. Isolation mediates persistent founder effects on zooplankton colonisation in new temporary ponds. Sci Rep 7, 43983 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43983

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43983

This article is cited by

-

Doing the Same Thing Over and Over Again and Getting the Same Result: Assessing Variance in Wetland Invertebrate Assemblages

Wetlands (2023)

-

Can the use of zooplankton dormant stages from natural wetlands contribute to restoration of mined wetlands?

Aquatic Ecology (2021)

-

The power of numbers: dynamics of hatching and dormant egg production in two populations of the water flea Daphnia magna

Aquatic Ecology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.