Abstract

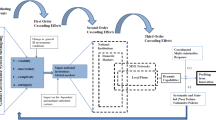

In this paper, we advance and test the idea that innovation and export are complementary strategies for SMEs’ growth. We argue that innovation and export positively reinforce each other in a dynamic virtuous circle, and we identify and describe the process through which this complementarity relationship takes place. Participating in export markets can promote firms’ learning, and thus enhance innovation performance. At the same time, through innovation, firms can enter new geographical markets with novel and better products, therefore making exports more successful, and, by the same token, they can also improve the quality – and consequently increase the sales – of the products sold domestically. We test our theory using an unbalanced panel of Spanish manufacturing firms over the period 1990–1999. We find robust empirical support for our hypothesis: consistent with the presence of complementarity, we show that the positive effect of innovation activity on firms’ growth rate is higher for firms that also engage in exports, and vice versa. Furthermore, we show that, Ceteris paribus, firms’ adoption of one growth strategy (e.g., entering export markets) positively influences the adoption of the other (e.g., innovation).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We assume no interaction with domestic sales, for the sake of simplicity.

The average proportion of the firms in year t that continue in the survey in year t+1 is approximately 91.5% for the 1990–1999 sample period. About 8.5% of firms exited the sample during this time period. Among the firms that exited the sample, approximately 2.6% disappeared due to closure, change to non-manufacturing activities and absorption during merger or acquisition. Approximately 3.3% of the exiting firms stopped collaborating, and about 2.6% were without access due to temporary closure or non-localizability.

The source for the producer price index defined at the two-digit NACE industry level is Instituto Nacional de Estadística (www.ine.es).

The test for complementarity is based on the definition of complementarity by Milgrom and Roberts (1990). Growth(Innovate&Export), Growth(OnlyInnovate), Growth(OnlyExport), and Growth(NoInnovate&NoExport) are the estimated coefficients on the firm's choice of different combinations of export and innovation in the growth regression (3). If the inequality (4) is true, that is, the complementarity test holds, it would mean that adding an activity (e.g., export) while the other activity is already performed (e.g., innovation) will result in higher incremental growth rates than when adding this activity in isolation.

To explain the adoption decisions of the different combinations of export and innovation choices we use a multinomial probit model, which, unlike multinomial logit, avoids the I.I.A. assumption and assumes that the errors can be correlated across choices. We use a cross-sectional model with the errors corrected for the intra-group (firm) correlation.

Following Campa (2004), we calculate an exchange rate index that reflects the changes in the peseta (the Spanish national currency over the period of analysis) with respect to other foreign currencies during 1990–1999, with higher values of the index corresponding to peseta depreciation periods. This index is firm specific, that is, it accounts for the fact that different firms may export to different markets and thus be differently affected by the exchange rate changes. It is calculated as a weighted average of the bilateral exchange rates of each of the potential export markets. For exporting firms, the information on the export markets is provided in the ESEE survey. The survey data distinguish among three broad export markets: EU (European Union) countries, other OECD countries, and the rest of the world. The computation of the exchange rate index is complicated, as the survey reports the information on the markets once in four years, that is, we have these data for 1990, 1994, and 1998. We calculate individual exchange rates for firms that were exporters in 1990, 1994, and 1998 by taking their export market to be equal to the one in the previous period. That is, for 1991–1993 we use the data for 1990, for 1995–1997 we use the information available in 1994, and for 1999 we use market destinations in 1998. For the firms that did not export in 1990 (1994) but exported in 1994 (1990), we define their markets as their 1994 (1990) pattern. The same procedure is applied to other combinations of 1990, 1994, and 1998. For firms that did not export during 1990–1999 we compute a weighted average of the EU, OECD, and other countries’ shares for Spain in that particular year.

Prior strategy research has used a similar approach to test the interrelationship between different strategic decisions. For instance, Salomon and Shaver (2005b) investigate the link between domestic and export sales by using simultaneous equation modeling and testing for the direct effect between these two variables.

The results of the Hansen test for the validity of over-identifying restrictions and the quality of instruments and Arellano–Bond test for the second-order serial autocorrelation of residuals support the validity of the model specification (Hansen test of over-identifying restrictions: χ2(27)=26.52; Prob>χ2=0.490; Arellano–Bond test for AR(2) in first differences: z=0.40 Pr>z=0.689).

Instead of conducting the test for the equality of means, we use a matching technique, as it allows to take into account relevant matching characteristics, such as firm size, export and R&D intensity, industry and year in which we observe the compared firms. We use the matching estimator developed by Abadie and Imbens (e.g., Abadie, Drukker, Herr, & Imbens, 2001; Abadie & Imbens, 2002) and estimate a model using a STATA routine developed by Abadie et al. (2001).

We used a CPI index (www.ine.es) to correct for the inflation during 1990–1999, and make the percentage of prices comparable over different time periods.

Another possible explanation regarding the importance of advertising intensity for the adoption of both export and innovation activities considers the difference between OEM suppliers and own-brand manufacturers, which might have different needs for innovation when exporting to foreign countries. Clearly, in the case of own-brand manufacturers, innovation is of greater importance and requires promoting in the foreign markets as these firms start exporting. We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this alternative explanation.

References

Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. W. 2002. Simple and bias-corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects, Working paper, University of California Berkeley.

Abadie, A., Drukker, D., Herr, J. L., & Imbens, G. W. 2001. Implementing matching estimators for average treatment in Stata. The Stata Journal, 1 (1): 1–18.

Acs, Z., & Audretsch, D. 1987. Innovation, market structure and firm size. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 69 (4): 567–574.

Alvarez, R., & Robertson, R. 2004. Exposure to foreign markets and plant-level innovation: Evidence from Chile and Mexico. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 13 (1): 57–87.

Ang, S. H. 2008. Competitive intensity and collaboration: Impact on firm growth across technological environments. Strategic Management Journal, 29 (10): 1057–1075.

Ansoff, I. H. 1965. Corporate strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Arora, A., & Gambardella, A. 1990. Complementarity and external linkages: The strategies of the large firms in biotechnology. Journal of Industrial Economics, 38 (4): 361–379.

Aw, B. Y., & Batra, G. 1998. Technology, exports and firm efficiency in Taiwanese manufacturing. Economics of Innovation & New Technology, 7 (2): 93–113.

Aw, B. Y., Chen, X., & Roberts, M. J. 2001. Firm-level evidence on productivity differentials and turnover in Taiwanese manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics, 66 (1): 51–86.

Aw, B. Y., Roberts, M. J., & Winston, T. 2007. Export market participation, investments in R&D and worker training, and the evolution of firm productivity. The World Economy, 30 (1): 83–104.

Basile, R. 2001. Export behaviour of Italian manufacturing firms over the nineties: The role of innovation. Research Policy, 30 (8): 1185–1201.

Becchetti, L., & Trovato, G. 2002. The determinants of growth for small and medium sized firms: The role of the availability of external finance. Small Business Economics, 19 (4): 291–306.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. 1999. Exceptional exporter performance: Cause, effect or both? Journal of International Economics, 47 (1): 1–25.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Scott, P. K. 2007. Firms in international trade. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (3): 105–130.

Braymen, C., Briggs, K., & Boulware, J. 2010. R&D and the export decision of new firms, Working paper, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1599657.

Bughin, J. 1996. Capacity constraints and export performance: Theory and evidence from Belgian manufacturing. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 44 (2): 187–204.

Campa, J. M. 2004. Exchange rates and trade: How important is hysteresis in trade? European Economic Review, 48 (3): 527–548.

Carroll, G. 1983. A stochastic model of organizational mortality: Review and reanalysis. Social Science Research, 12 (4): 309–329.

Cassiman, B., & Golovko, E. 2010. Innovation and internationalization through exports. Journal of International Business Studies, 42 (1): 56–75.

Cassiman, B., & Martinez-Ros, E. 2007. Innovation and exports: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing, IESE working paper, Mimeo.

Cassiman, B., & Veugelers, R. 2006. In search of complementarity in innovation strategy: Internal R&D, cooperation in R&D and external knowledge acquisition. Management Science, 52 (1): 68–82.

Cho, H., & Pucik, V. 2005. Relationship between innovativeness, quality, growth, profitability, and market value. Strategic Management Journal, 26 (6): 555–575.

Clerides, S. K., Lach, S., & Tybout, J. R. 1998. Is learning-by-exporting important? Micro-dynamic evidence from Colombia, Mexico and Morocco. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113 (3): 903–947.

Cohen, W., & Klepper, S. 1996. Firm size and the nature of innovation within industries: The case of process and product R&D. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78 (2): 232–243.

Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. 1990. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35 (1): 128–152.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. 2003. Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18 (2): 189–216.

Ebben, J. J., & Johnson, A. C. 2005. Efficiency, flexibility, or both? Evidence linking strategy to performance in small firms. Strategic Management Journal, 26 (13): 1249–1259.

Evans, D. 1987. The relationship between firm growth, size, and age: Estimates for 100 manufacturing industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35 (4): 567–581.

Filatotchev, I., & Piesse, J. 2009. R&D, internationalization and growth of newly listed firms: European evidence. Journal of International Business Studies, 40 (8): 1260–1276.

Freeman, J., Carroll, G. R., & Hannan, M. T. 1983. The liability of newness: Age dependence in organizational death rates. American Sociological Review, 48 (5): 692–710.

Geroski, P. 1999. The growth of firms in theory and in practice, CEPR Discussion Paper DP2092.

Geroski, P. 2005. Understanding the implications of empirical work on corporate growth rates. Managerial and Decision Economics, 26 (2): 129–138.

Geroski, P., Machin, S., & Van Reenen, J. 1993. The profitability of innovating firms. Rand Journal of Economics, 24 (2): 198–211.

Gilbert, B. A., McDougall, P., & Audretsch, D. B. 2006. New venture growth: A review and extension. Journal of Management, 32 (6): 926–950.

Goldberg, P. K., & Knetter, M. M. 1997. Goods prices and exchange rates: What have we learned? Journal of Economic Literature, 35 (3): 1243–1272.

Griffith, R., Huergo, E., Mairesse, J., & Peeters, B. 2006. Innovation and productivity across four European countries, NBER Working paper W12722, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hamilton, B. H., & Nickerson, J. A. 2003. Correcting for endogeneity in strategic management research. Strategic Organization, 1 (1): 51–78.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Kim, H. 1997. International diversification: Effects of innovation and firm performance in product diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, 40 (4): 767–798.

Huergo, E., & Jaumandreu, J. 2004. Firms’ age, process innovation and productivity growth. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 22 (4): 541–559.

Iacovone, L., & Javorcik, B. 2009. Shipping good tequila out: Investment, domestic unit values and entry of multi-product plants into export markets, University of Oxford, mimeo.

Knight, G., & Cavusgil, S. T. 2004. Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35 (2): 124–141.

Kumar, M. V. S. 2009. The relationship between product and international diversification: The effects of short-run constraints and endogeneity. Strategic Management Journal, 30 (1): 99–116.

Lu, J., & Beamish, P. 2001. Internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (6/7): 565–586.

Lu, J., & Beamish, P. 2006. SME internationalization and performance: Growth vs profitability. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 4 (1): 27–48.

McDougall, P. P., & Oviatt, B. M. 1996. New venture internationalization, strategic change, and performance: A follow-up study. Journal of Business Venturing, 11 (1): 23–41.

McGuinness, N., & Little, B. 1981. The influence of product characteristics on the export performance of new industrial products. The Journal of Marketing, 45 (2): 110–122.

Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. 1990. The economics of modern manufacturing: Technology, strategy, and organization. American Economic Review, 80 (3): 511–528.

Mowery, D., & Rosenberg, N. 1979. The influence of market demand upon innovation: A critical review of some recent empirical studies. Research Policy, 8 (2): 102–153.

OECD. 2002. High-growth SMEs and employment. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Porter, M. 1996. What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74 (6): 61–80.

Porter, M., & Siggelkow, N. 2007. Contextuality within activity systems and sustainability of competitive advantage, Wharton Working Paper, University of Pennsylvania.

Rivkin, J. 2000. Imitation of complex strategies. Management Science, 46 (6): 824–844.

Roberts, M., & Tybout, J. 1997. The decision to export in Colombia: An empirical model of entry with sunk costs. American Economic Review, 87 (4): 545–564.

Roberts, M., & Tybout, J. 1999. An empirical model of sunk cost and the decision to export, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 1436.

Robson, P., & Bennett, R. 2000. SME growth: The relationship with business advice and external collaboration. Small Business Economics, 15 (3): 193–208.

Roper, S., & Love, J. H. 2002. Innovation and export performance: Evidence from the UK and German manufacturing plants. Research Policy, 31 (7): 1087–1102.

Ross, S. A., Westerfield, R. W., & Jaffe, J. 1999. Corporate finance, (5th ed.) Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

Salomon, R. 2006. Spillovers to foreign market participants: Assessing the impact of export strategies on innovative productivity. Strategic Organization, 4 (2): 135–164.

Salomon, R., & Jin, B. 2008. Does knowledge spill to leaders or laggards? Exploring industry heterogeneity in learning by exporting. Journal of International Business Studies, 39 (1): 132–150.

Salomon, R., & Shaver, J. M. 2005a. Learning-by-exporting: New insights from examining firm innovation. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 14 (2): 431–461.

Salomon, R., & Shaver, J. M. 2005b. Export and domestic sales: Their interrelationship and determinants. Strategic Management Journal, 26 (9): 855–871.

Sapienza, H. J., Autio, E., George, G., & Zahra, S. A. 2006. A capabilities perspective on the effects of early internationalization on firm survival and growth. Academy of Management Journal, 31 (4): 914–933.

Shaver, J. M. 1998. Accounting for endogeneity when assessing strategy performance: Does entry mode choice affect FDI survival? Management Science, 44 (4): 571–585.

Shaver, J. M. 2011. The benefits of geographic sales diversification: How exporting facilitates capital investment. Strategic Management Journal, published online, DOI: 10.1002/smj.924.

Shrader, R. C., Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. 2000. How new ventures exploit trade-offs among international risk factors: Lessons for the accelerated internationalization of the 21st century. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (6): 1227–1247.

Siegel, R., Siegel, E., & MacMillan, I. C. 1993. Characteristics distinguishing high-growth ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 8 (2): 169–180.

Sterlacchini, A. 1999. Do innovative activities matter to small firms in non-R&D-intensive industries? An application to export performance. Research Policy, 28 (8): 819–832.

Teece, D. J. 1986. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy, 15 (6): 285–305.

Weinzimmer, L. G., Nystrom, P. C., & Freeman, S. J. 1998. Measuring organizational growth: Issues, consequences and guidelines. Journal of Management, 24 (2): 235–262.

Yasuda, T. 2005. Firm growth, size, age and behaviour in Japanese manufacturing. Small Business Economics, 24 (1): 1–15.

Young, J., Wheeler, C., & Davies, J. R. 1989. International market entry and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Zahra, S. A., & Covin, J. G. 1994. Domestic and international competitive focus, technology strategy and firm performance: An empirical analysis. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 6 (1): 39–53.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate helpful and constructive comments from the Editor, Myles Shaver, three anonymous reviewers, Bruno Cassiman, Jose Manuel Campa, Gianluca Carnabuci, Guido Corbetta, Marta Maras, Robert Salomon, and Xavier Martin, as well as seminar participants at Carlos III University and CESPRI-Bocconi. We are grateful to the Fundacion Empresa Publica for providing access to these data. The financial support from the Catalan Government Grant No. 2009-SGR919 is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by Myles Shaver, Consulting Editor, 1 November 2010. This paper has been with the author for two revisions.

APPENDIX

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Golovko, E., Valentini, G. Exploring the complementarity between innovation and export for SMEs’ growth. J Int Bus Stud 42, 362–380 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.2