Abstract

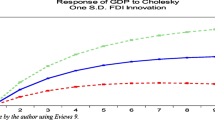

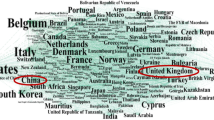

This paper examines the risk of US direct foreign investments over the period 1982–98 in 59 host countries. The first part of the analysis builds an empirical model to explain the time-series and cross-country patterns of return on capital. The estimation then uses the return on assets (ROA) as a measure of the return on capital, and investigates its determinants. There are four main findings. First, the ROA in a majority of countries does not simply track the worldwide ROA. Second, some cross-country differences are explained by financial risks. Third, unexplained country risk is qualitatively and quantitatively related to unobserved political risk. Fourth, unexplained country risk is also compensated with a higher ROA, enhancing its credibility as a measure of political risk. The unexplained country risk is thus used to calculate a new index of political risk ratings for 56 host countries that may be useful to managers, investors, policymakers, and academics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Lehmann (2002) uses variances of returns on assets and sales as measures of risk, which are subsequently linked to country-specific risk emanating from political uncertainty (but not decomposed). Lehmann develops a model and conducts an empirical investigation of the allocation of capital by US MNCs across foreign countries, and finds that capital stocks are high in countries with a history of high returns and low variability.

The term ‘peso problem’ is from the literature on the foreign exchange market. With reference to the Mexican peso during its fixed exchange rate regime, there was a ‘problem’ in the forward market data when market expectations ex ante reflected the probability of an event, such as devaluation (or imposition of exchange or capital controls), that did not occur ex post.

Income statement and balance sheet items conform to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. The net income is the sum of: (1) sales; (2) income from equity investments; (3) capital gains; and (4) other income, minus the sum of: (1) cost of goods sold and selling, general, and administrative expenses; (2) foreign income taxes; and (3) other expenses. Total assets include: (1) net property, plant, and equipment; (2) equity investment in other foreign affiliates; (3) other non-current assets; (4) inventories; and (5) other current assets. Analysis is restricted to the category ‘Majority-Owned Nonbank Foreign Affiliates of Nonbank US Parents’ in order to focus on the DFI in which US investors have control, and to exclude banking activities.

With 59 countries and 17 years, the total number of observations would be 1003. Data for Libya and Liberia end in 1988, removing 20 possible observations. Data for Barbados, China, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Honduras begin in 1989, removing 42 possible observations. Two years of data from Trinidad and Tobago are suppressed by the DOC in order to preserve confidentiality of firms operating there.

The number of observations in the regression is 877. The size of the panel is 939 observations. The observation for Peru in 1990 ( −24%) is deleted because the Dixon Q test rejects the hypothesis that it is not an outlier. Since both Peru and Trinidad and Tobago have breaks in the series, the total number of observations discarded in order to implement the adjustment lag is 59 + 2=61, leaving 939 −1 −61=877 observations for the regression.

The country data are predominantly from the International Monetary Fund's International Financial Statistics database. The nominal growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP) in local currency is calculated from line 99b as the logarithmic change from the previous year. The percentage change in the US dollar per foreign currency exchange rate is the logarithmic change in the annual average exchange rate from line ah. The interest rate is the most complete interest rate series available in the database, with preference given to government treasury bill rates in line 60c. The local inflation rate is calculated as the logarithmic change in the consumer price index (CPI) from line 64. Data for Taiwan are from the Europa World Yearbook and data for Bermuda are from the United Nations’ National Account Statistics (except the exchange rate for Bermuda is simply B$=US$). At this stage, three countries drop out of the analysis owing to lack of some data: Libya and United Arab Emirates do not have data on the CPI, and Netherlands Antilles does not have data on GDP.

Time series of the Euromoney and Institutional Investor ratings are compiled from hard copies of the magazines; the ratings from Euromoney are the ratings from September or October of the year (although 1998 was reported in December), and the ratings from Institutional Investor are consistently from September of the year. Time series for ICRG are September observations purchased from www.CountryData.com. For all series, data for Germany splice together data for West Germany up through 1990 and data for unified Germany thereafter.

Netherlands Antilles, the least risky of all countries, drops out owing to lack of data on GDP. Peru, the riskiest country, becomes safer once the outlier observation is removed; the standard deviation of ROA without the 1990 observation is 5.30.

We also computed an adjusted rating to account for the degree to which US assets in each country are spread across the six industry classifications tracked by the DOC. The concern is that heterogeneous investments within a country may serve to diversify and reduce the risk of capital deployed there, lowering the standard deviation of residuals, but that political risk ratings should not reward countries where DFI is well diversified (penalizing countries where DFI is not well diversified). The adjustment is somewhat rudimentary because more than 18% of the observations are not reported by the DOC. However, a simple regression suggests that diversification is associated with lower risk. Empirically, there are some differences between the unadjusted and adjusted ratings, but the correlation coefficient is 0.86, so the indices are in fact highly similar. The adjustment does not affect any of the results presented in the rest of the paper, so to conserve space we do not report the adjusted rating or results using it.

The correlation between σ i and average per capita gross national income (typically the single most important determinant of country risk) over the period 1982–98 is −0.392. Two other specific elements of political risk were also considered. Transparency International reports a corruption perceptions index in which a low value represents high corruption; it is available on www.transparency.org. The correlation of σ i with the average Transparency International index over 1982–98 is −0.423. The Heritage Foundation provides an index of economic freedom in which a low value represents high freedom; this is available in O'Driscoll et al. (2000). The correlation with the average of 1995–98 is 0.335. These further suggest that σ i is related to various country and political risks conventionally defined.

References

Barber, B.M., Click, R.W. and Darrough, M.N. (1999) ‘The impact of shocks to exchange rates and oil prices on US sales of American and Japanese automakers’, Japan and the World Economy 11 (1): 57–93.

Bartov, E. and Bodnar, G.M. (1994) ‘Firm valuation, earnings expectations, and the exchange-rate exposure effect’, Journal of Finance 49 (5): 1755–1785.

Bilson, C.M., Brailsford, T.J. and Hooper, V.C. (2002) ‘The explanatory power of political risk in emerging markets’, International Review of Financial Analysis 11 (1): 1–27.

Butler, K.C. and Joaquin, D.C. (1998) ‘A note on political risk and the required return on foreign direct investment’, Journal of International Business Studies 29 (3): 599–608.

Campos, N.F. and Nugent, J.B. (2002) ‘Who is afraid of political instability?’ Journal of Development Economics 67 (1): 157–172.

Cantor, R. and Packer, F. (1996a) ‘Determinants and impact of sovereign credit ratings’, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review 2 (2): 37–54.

Cantor, R. and Packer, F. (1996b) ‘Sovereign risk assessment and agency credit ratings’, European Financial Management 2 (2): 247–256.

Choi, J.J. (1989) ‘Diversification, exchange risks, and corporate international investment’, Journal of International Business Studies 20 (1): 145–155.

Choi, J.J. and Rajan, M. (1997) ‘A joint test of market segmentation and exchange risk factor in international capital markets’, Journal of International Business Studies 28 (1): 29–49.

Click, R.W. and Coval, J.D. (2002) The Theory and Practice of International Financial Management, Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Cosset, J.-C. and Roy, J. (1991) ‘The determinants of country risk ratings’, Journal of International Business Studies 22 (1): 135–142.

Cosset, J.-C., Daouas, M., Kettani, O. and Oral, M. (1993) ‘Replicating country risk ratings’, Journal of Multinational Financial Management 3 (1/2): 1–29.

Diamonte, R.L., Liew, J.M. and Stevens, R.L. (1996) ‘Political risk in emerging and developed markets’, Financial Analysts Journal 52 (3): 71–76.

Erb, C.B., Harvey, C.R. and Viskanta, T.E. (1996) ‘Political risk, economic risk, and financial risk’, Financial Analysts Journal 52 (6): 29–46.

Ferri, G., Liu, L.-G. and Stiglitz, J.E. (1999) ‘The procyclical role of rating agencies: evidence from the East Asian crisis’, Economic Notes by Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA 28 (3): 335–355.

Gomes-Casseres, B. and Jenkins, M. (2003) ‘Value destruction in joint ventures? Why US JVs abroad are less profitable than wholly owned ventures’, Unpublished Manuscript Presented at the Academy of International Business Annual Meeting.

Habib, M. and Zurawicki, L. (2002) ‘Corruption and foreign direct investment’, Journal of International Business Studies 33 (2): 291–307.

Howell, L.D. (2001) The Handbook of Country and Political Risk Analysis (3rd edn), The PRS Group: East Syracuse, NY.

Jorion, P. (2001) Value at Risk, 2nd edn, McGraw-Hill: New York.

Kaminsky, G. and Schmukler, S. (2002) ‘Emerging market instability: do sovereign ratings affect country risk and stock returns?’ The World Bank Economic Review 16 (2): 171–195.

Lehmann, A. (2002) ‘The distribution of fixed capital in the multinational firm’, IMF Staff Papers 49 (1): 136–153.

Moran, T.H. (1998) Managing International Political Risk, Blackwell Publishers: Malden, MA.

O'Driscoll Jr., G.P., Holmes, K.R. and Kirkpatrick, M. (2000) Index of Economic Freedom, The Heritage Foundation: Washington, DC and Dow Jones & Company: New York, NY.

Oetzel, J.M., Bettis, R.A. and Zenner, M. (2001) ‘Country risk measures: how risky are they?’ Journal of World Business 36 (2): 128–145.

Oxelheim, L. and Wihlborg, C. (1997) Managing in the Turbulent World Economy: Corporate Performance and Risk Exposure, John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester.

Reinhart, C.M. (2002) ‘Default, currency crises, and sovereign credit ratings’, The World Bank Economic Review 16 (2): 151–170.

US Department of Commerce (various years) US Direct Investment Abroad: Operations of Parent Companies and Their Affiliates, US Department of Commerce: Washington, DC.

Wei, S.-J. (2000) ‘How taxing is corruption on international investors?’ Review of Economics and Statistics 82 (1): 1–11.

White, H. (1980) ‘A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and direct test for heteroskedasticity’, Econometrica 48 (4): 817–838.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for financial support from the GW Center for the Study of Globalization to conduct this research. The project has also benefited from comments from: Harvey Arbeláez, Tom Hall, Jennifer Oetzel, Jennifer Spencer, Ozan Sula, Raj Aggarwal, and three anonymous referees of this journal; seminar participants at the Akademia Gorniczo Hutnicza University of Science and Technology in Krakow and the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies Bologna Center; and conference participants at the 2003 Academy of International Business Conference, the 2003 Western Economics Association International Conference, and the 2004 Southern Economic Association Conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by Raj Aggarwal, 11 February 2005. This paper has been with the author for two revisions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Click, R. Financial and political risks in US direct foreign investment. J Int Bus Stud 36, 559–575 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400157

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400157