Abstract

This paper updates and expands the database on systemic banking crises presented in Laeven and Valencia (IMF Econ Rev 61(2):225–270, 2013a). The database draws on 151 systemic banking crisis episodes around the globe during 1970–2017 to include information on crisis dates, policy responses to resolve banking crises, and their fiscal and output costs. We provide new evidence that crises in high-income countries tend to last longer and be associated with higher output losses, lower fiscal costs, and more extensive use of bank guarantees and expansionary macro-policies than crises in low- and middle-income countries. We complement the banking crisis dates with sovereign debt and currency crises dates to find that sovereign debt and currency crises tend to coincide with or follow banking crises.

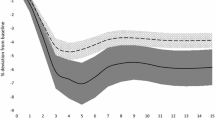

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: World Economic Outlook, IMF, IFS, and authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples of such severity include Latvia’s 1995 crisis, when banks totaling 40% of the financial system’s assets were closed, and more recently, Moldova (2014) and Ukraine (2014).

We express our measure of fiscal costs in terms of GDP. However, whenever available, we also report fiscal costs expressed in % of financial system assets.

Other researchers (e.g., Demirgüç-Kunt and Detragiache 1998) have used milder thresholds resulting in more crisis episodes. However, milder thresholds tend to increase the proportion of non-systemic events in the sample, while our focus is on systemic crises.

Although we do not consider a quantitative threshold for this criterion, in all cases, guarantees involved significant financial sector commitments relative to the size of the corresponding economies.

Laeven and Valencia (2013a) also present information on whether a previous explicit deposit insurance arrangement was in place at the time of the introduction of the blanket guarantee.

This measure of liquidity would also capture the impact of currency swap lines among central banks, agreed during the global financial crisis, to the extent that they were used to inject liquidity in the financial sector.

We use the end-of-period official nominal bilateral exchange rates from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook (WEO) database. For countries that meet the currency crisis criteria for several consecutive years, we use the first year of each 5-year window to identify the crisis. While our approach resembles that of Frankel and Rose (1996), our thresholds are not identical to theirs.

As in Laeven and Valencia (2013a), we exclude from the list currency crises that occur in countries that were early in the process of transition toward market economies.

We define a twin crisis in year T as a banking crisis in year T, combined with a currency (sovereign debt) crisis during the period [T − 1, T + 1], and we define a triple crisis in year t as a banking crisis in year T, combined with a currency crisis during the period [T − 1, T + 1] and a sovereign debt crisis during the period [T − 1, T + 1]. Identifying the overlap between banking (currency) and sovereign crises follows the same approach, with t the year of a banking (currency) crisis.

We exclude domestic non-deposit liabilities from the denominator of this ratio because information on such liabilities is not readily available on a gross basis.

Laeven and Valencia (2013a) also report the increase in reserve money across episodes, which also captures the use of unconventional monetary policy, to conclude the greater use of monetary policy in high-income countries. We have streamlined the accompanying data file to facilitate use and to include only variables where the updating was feasible. Therefore, we exclude a few variables from the current release, but the reader can still find them in Laeven and Valencia (2013a).

Our calculation of fiscal costs also excludes deferred tax assets (i.e., for Spain, these deferred tax assets amounted to €70 billion as of end-2016 according to IMF 2017).

We report the fiscal costs in % of GDP, where nominal fiscal costs, expressed first in domestic currency, are divided by the nominal GDP of the corresponding year when the outlays took place.

We take the fiscal costs and recoveries from Laeven and Valencia (2013a). For episodes starting in 2007 or later, we updated the fiscal costs and recoveries using official national publications. For European countries, whenever national sources did not publish information on these costs, we took data from the European commission scoreboard and Eurostat (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/government-finance-statistics/excessive-deficit/supplemtary-tables-financial-crisis).

A case in point is Iceland, where we report net fiscal costs for 3.3% of GDP, which excludes bank equity held by the government valued at approximately 12% of GDP in 2016. This exclusion explains the bulk of the difference between our estimates of the net fiscal costs and the -9% of GDP reported in the 2016 IMF Article IV Staff Report.

For most countries, the financial system assets data are taken from the World Bank’s Financial Structure database and consist of domestic claims on the private sector by banks and non-bank financial institutions. In the case of European Union countries, for which cross-border claims can be sizeable, we instead use data from the European Central Bank (ECB) on the consolidated assets of financial institutions (excluding the Eurosystem and other national central banks), after netting out the aggregated balance sheet positions between financial institutions. Moreover, in the case of Iceland, where cross-border claims are also sizable, we use the assets of monetary and other financial institutions obtained from its national central bank.

A handful of episodes appear with fiscal costs of more than 100% of financial system assets. This anomaly is the outcome of hyperinflation since we take financial system assets as of the year preceding the banking crisis and fiscal outlays as of the year when they are incurred.

We approximate the increase in public debt by computing the difference between pre- and post-crisis debt projections. For crises starting in 2007 or later, we use as pre-crisis projected debt increase, between T − 1 and T + 3, reported in the World Economic Outlook (WEO) issued in the fall of the year before the crisis start date (T) while the post-crisis actual debt increase, again over T − 1 and T + 3, is based on data from the Fall 2017 WEO. The ratios to GDP are computed using the latest GDP series. For past episodes, we report the actual change in debt.

In computing end dates, we use bank credit to the private sector (in national currency) from IFS (line 22d). Bank credit series is deflated using CPI from WEO. GDP in constant prices (in national currency) also comes from the WEO. When credit data are not available, we determine the end date as the first year before GDP growth is positive for at least 2 years. When the definition is met in the first year of the crisis, then we set the crisis end year equal to the starting year.

We calculate output losses as the cumulative sum of the differences between actual and trend real GDP over the period [T, T + 3], expressed as a percentage of trend real GDP, with T the starting year of the crisis. We compute trend real GDP using an HP filter (with λ = 100) to the log of real GDP series over the period [T − 20, T − 1] or the longest available series as long it includes at least 4 pre-crisis observations. We extrapolate real GDP using the trend growth rate over the same period. Real GDP data come from the fall 2017 WEO.

Cerra and Saxena (2017) argue that on average, all types of recessions, not just those associated with financial and political crises, lead to permanent output losses.

This conclusion is different than the one in Mishkin (1996), written before the global financial crisis, which affected mostly advanced countries with intensity and global proportion not seen since the Great Depression.

References

Abbassi, Puriya, Raj Iyer, Jose-Luis Peydro, and Francesc R. Tous. 2016. Securities Trading by Banks and Credit Supply: Micro-Evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 121(3): 569–594.

Abiad, Abdul, Ravi Balakrishnan, Petya Koeva Brooks, Daniel Leigh, and Irina Tytell. 2014. “What’s the Damage? Medium-Term Output Dynamics After Financial Crises. In Financial Crises: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses, ed. M. Stijn Claessens, Ayhan Kose, Luc Laeven, and Fabian Valencia. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Alfaro, Laura, Manuel Garcia-Santana, and Enrique Moral-Benito. 2017. Credit Supply Shocks, Network Effects, and the Real Economy. Harvard Business School Manuscript.

Ashcraft, Adam. 2005. Are Banks Really Special? New Evidence from the FDIC-Induced Failure of Healthy Banks. American Economic Review 95: 1712–1730.

Aslam, Aqib, Patrick Blagrave, Eugenio Cerutti, Sung Eun Jung, and Carolina Osorio-Buitron. Recessions and Recoveries: Are EMs Different from AEs? IMF Working Paper (forthcoming).

Åslund, Anders. 2009. Ukraine’s Financial Crisis. Eurasian Geography and Economics 50(4): 371–386.

Bakker, Bas B., and Christoph Klingen. 2012. How Emerging Europe Came Through the 2008/09 CRISIS: An Account by the Staff of the IMF’s European Department. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Baron, Matthew, Emil Verner, and Wei Xiong. 2018. Identifying Banking Crises. Princeton University Manuscript.

Beim, David, and Charles Calomiris. 2001. Emerging Financial Markets. Appendix to Chapter 1. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bernanke, Ben, and Mark Gertler. 1987. Banking and Macroeconomic Equilibrium. In New Approaches to Monetary Economics, ed. W. Barnett and K. Singleton. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Caprio, Gerard, and Daniela Klingebiel. 1996. Bank Insolvencies: Cross-Country Experience. Policy Research Working Paper No. 1620. Washington: World Bank.

Cerra, Valerie, and Sweta Saxena. 2008. Growth Dynamics: The Myth of Economic Recovery. American Economic Review 98(1): 439–457.

Cerra, Valerie, and Sweta Saxena. 2017. Booms, Crises, and Recoveries: A New Paradigm of the Business Cycle and Its Policy Implications. IMF Working Paper 2017/250. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Chaudron, Raymond, and Jakob de Haan. 2014. Dating Banking Crises Using Incidence and Size of Bank Failures: Four Crises Reconsidered. Journal of Financial Stability 15: 63–75.

Claessens, Stijn, M. Ayhan Kose, Luc Laeven, and Fabian Valencia (eds.). 2014. Financial Crises: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Claessens, Stijn, Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, Luc Laeven, Marc Dobler, Fabian Valencia, Oana Nedelescu, and Katharine Seal. 2011. Crisis Management and Resolution: Early Lessons from the Financial Crisis. IMF Staff Discussion Note No. 11/05.

Cruces, Juan J., and Christoph Trebesch. 2013. Sovereign Defaults: The Price of Haircuts. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5(3): 85–117.

Dell’Ariccia, Giovanni, Enrica Detragiache, and Raghuram Rajan. 2008. The Real Effects of Banking Crises. Journal of Financial Intermediation 17: 89–112.

Dell’Ariccia, Giovanni, Maria Soledad Martinez Peria, Deniz O Igan, Elsie Addo Awadzi, Marc Dobler, and Damiano Sandri. 2018. Trade-Offs in Bank Resolution. IMF Staff Discussion Note 18/02. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, and Enrica Detragiache. 1998. The Determinants of Banking Crises: Evidence from Developed and Developing Countries. IMF Staff Papers 45(1): 81–109.

Frankel, Jeffrey, and Andrew Rose. 1996. Currency Crashes in Emerging Markets: An Empirical Treatment. Journal of International Economics 41: 351–366.

Fratzscher, Marcel, Arnaud Mehl, and Isabel Vansteenkiste. 2011. 130 Years of Fiscal Vulnerabilities and Currency Crashes in Advanced Economies. IMF Economic Review 59: 683–716.

Giannetti, Mariassunta, and Andrei Simonov. 2013. On the Real Effects of Bank Bailouts: Micro Evidence from Japan. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5: 135–167.

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Maurice Obstfeld. 2012. Stories of the Twentieth Century for the Twenty-First. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 4(1): 226–265.

Homar, Timotej, and Sweder J.G. van Wijnbergen. 2017. Bank Recapitalization and Economic Recovery After Financial Crises. Journal of Financial Intermediation 32: 16–28.

Honohan, Patrick, and Luc Laeven (eds.). 2005. Systemic Financial Crises: Containment and Resolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

IMF. 2014. From Banking to Sovereign Stress: Implications for Public Debt. IMF Board Paper. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IMF. 2016. Global Trade: What’s Behind the Slowdown? IMF World Economic Outlook, Chapter 2. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IMF. 2017. Spain—Publication of Financial Sector Assessment Program Documentation—Technical Note on Impaired Assets and Nonperforming Loans. IMF Country Report No. 17/343. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Jorda, Oscar, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. 2015. Leveraged Bubbles. Journal of Monetary Economics 76: S1–S20.

Kaminsky, Graciela, and Carmen Reinhart. 1999. The Twin Crises: The Causes of Banking and Balance-of-Payments Problems. American Economic Review 89: 473–500.

Kohlscheen, Emanuel, Fernando Avalos, and Andreas Schrimpf. 2017. When the Walk is Not Random: Commodity Prices and Exchange Rates. International Journal of Central Banking 13(2): 121–158.

Kroszner, Randall, Luc Laeven, and Daniela Klingebiel. 2007. Banking Crises, Financial Dependence, and Growth. Journal of Financial Economics 84: 187–228.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2008. Systemic Banking Crises: A New Database. IMF Working Paper No. 08/224. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2010. Resolution of Banking Crises: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. IMF Working Paper No. 10/44. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2012. The Use of Blanket Guarantees in Banking Crises. Journal of International Money and Finance 1(5): 1220–1248.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2013a. Systemic Banking Crises Database. IMF Economic Review 61(2): 225–270.

Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2013b. The Real Effects of Financial Sector Interventions During Crises. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 45(1): 147–177.

Lane, Philip R. 2012. The European Sovereign Debt Crisis. Journal of Economic Perspectives 26(3): 49–68.

Mishkin, Frederic. 1996. Understanding Financial Crises: A Developing Country Perspective. NBER Working Paper No. 5600.

Mody, Ashoka, and Damiano Sandri. 2012. The Eurozone Crisis: How Banks and Sovereigns Came to be Joined at the Hip. Economic Policy 27(70): 199–230.

Obstfeld, Maurice. 2013. Finance at Center Stage: Some Lessons of the Euro Crisis. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 9415.

Peek, Joe, and Erik Rosengren. 1997. The International Transmission of Financial Shocks: The Case of Japan. American Economic Review 87(4): 495–505.

Philippon, Thomas, and Philipp Schnabl. 2013. Efficient Recapitalization. Journal of Finance 68(1): 1–42.

Reinhart, Carmen, and Kenneth Rogoff. 2009. This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Reinhart, Carmen, and Kenneth Rogoff. 2011. From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis. American Economic Review 101: 1676–1706.

Romer, David, and Christina Romer. 2017. New Evidence on the Aftermath of Financial Crises in Advanced Countries. American Economic Review 107(10): 3072–3118.

Romer, David, and Christina Romer. 2018. Phillips Lecture—Why Some Times are Different: Macroeconomic Policy and the Aftermath of Financial Crises. Economica 85: 1–40.

Sandri, Damiano, and Fabian Valencia. 2013. Financial Crises and Recapitalizations. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 45(S2): 59–86.

Schularick, Moritz, and Alan M. Taylor. 2012. Credit Booms Gone Bust: Monetary Policy, Leverage Cycles, and Financial Crises, 1870–2008. American Economic Review 102(2): 1029–1061.

Shambaugh, Jay C. 2012. The Euro’s Three Crises. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 43(1): 157–231.

Stone, M., K. Fujita, and K. Ishi. 2011. Should Unconventional Balance Sheet Policies Be Added to the Central Bank Toolkit?. IMF Working Paper 2011/145.

Sturzenegger, Federico, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer. 2006. Debt Defaults and Lessons from a Decade of Crises. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Valencia, Fabian. 2014. Banks’ Precautionary Capital and Credit Crunches. Macroeconomic Dynamics 18(8): 1726–1750.

Van Den Heuvel, Skander. 2006. The Bank Capital Channel of Monetary Policy. University of Pennsylvania Unpublished Manuscript.

World Bank. 2002. Global Development Finance. Appendix on Commercial Debt Restructuring. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Linda Tesar (the Editor), two anonymous referees, Sergei Antoshin, Ashok Bhatia, Raymond Chaudron, Luis Cortavarria-Checkley, Ingimundur Friðriksson, Vikram Haksar, Samba Mbaye, Aiko Mineshima, Herimandimby Razafindramanana, Mohamed Sidi Bouna, and Jón Þ. Sigurgeirsson for insightful comments and Eugenia Menaguale, Sandra Daudignon, and Carl-Wolfram Horn for outstanding research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the ECB, the Eurosystem, the IMF, the IMF Executive Board, or IMF Management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.