Abstract

Computational folkloristics, which is rooted in the movement to make folklore studies more scientific, has transformed the way researchers in humanities detect patterns of cultural transmission in large folklore collections. This interdisciplinary study contributes to the literature through its application of Bayesian statistics in analyzing Vietnamese folklore. By breaking down 307 stories in popular Vietnamese folktales and major story collections and categorizing their core messages under the values or anti-values of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, the study shows how the Bayesian method helps discover an underlying behavioural phenomenon called “cultural additivity.” The term, which is inspired by the principle of additivity in probability, adds to the voluminous works on syncretism, creolization and hybridity in its technical dimension. Here, to evaluate how the values and norms of the aforementioned three religions (“tam giáo” 三教) co-exist, interact, and influence Vietnamese society, the study proposes three models of additivity for religious faiths: (a) no additivity, (b) simple additivity, and (c) complex additivity. The empirical results confirm the existence of “cultural additivity” : not only is there an isolation of Buddhism in the folktales, there is also a higher possibility of interaction or addition of Confucian and Taoist values even when these two religions hold different value systems (β{VT.VC} = 0.86). The arbitrary blend of the three religions is an example of the observed phenomenon of Vietnamese people selecting and adding ideas, beliefs, or artefacts—which may sometimes appear contradictory to principles of their existing beliefs—to their culture. The behavioural pattern is omnipresent in the sense that it can also be seen in Vietnamese arts, architecture, or adoption of new ideas and religions, among others. The “cultural additivity” concept, backed by robust statistical analysis, is an attempt to fill in the cultural core pointed out by syncretism and account for the rising complexity of modern societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The move toward a more scientific approach of folklore studies could be dated back to the nineteenth century, when scholars were first keen on having the traditional expressive culture reflect a Darwinian theory of biological evolution (Bronner, 2005; Magliocco, 2010). The enlightened scientific forces not only suggest a disintegration of racial boundaries but also result in an ambivalence toward the value of the “old” beliefs and customs (Bronner, 2005). As this movement is aided with the rapid development of information technology, a sub-field of folklore studies called computational folkloristics has emerged and now expanded throughout the world. This sub-field has five main targets: (i) digitizing resources into machine readable forms, (ii) developing data structures to store these resources, (iii) classifying folklores, (iv) developing domains sensitive methods, and (v) applying algorithms (Abello et al., 2012; Tangherlini, 2013; Nguyen et al., 2013; Dogra, 2018; Da Silva and Tehrani, 2016). Abello et al. (2012) use the term “distant reading” that was coined by Moretti (2000) when predicting the future of humanities in the information age. Here, researchers in humanities, backed by machines and algorithms, are liberated from the obscurity of the details in the text and are able to discover patterns, themes, devices, tropes, genres and systems (Moretti, 2000). One of the most ambitious endeavors is the “historical-geographic” method, pioneered by Finnish folklorists Julius and Kaarle Krohn (Thompson, 1977), in which the exponents seek to reconstruct the history of the evolution of one original folktale into multiple variants by sorting all available variants by regions and timelines (Tehrani and d’Huy, 2017).

These projects, however advanced and ambitious they are, have mostly taken a comparative cross-cultural approach (Nguyen et al., 2013; Bortolini et al., 2017a, b; d’Huy et al., 2017). Of the computational folklore studies that are more country-specific, such as the study on Russian tales by Propp (2010) or Croatian tongue-twister by Nikolić and Bakarić (2016) or Korean tales by Choi and Kim (2013), the number of such research in Asia appears to be limited. Filling in this gap and taking advantage of Bayesian analysis, this study sets out to detect the behavioural patterns in hundreds of Vietnamese folktales that are influenced by the three religions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. By breaking these religiously complex narratives into their constituent parts, the study not only discovered the co-existence and interaction of elements from the three religions in the folktales, but also was able to infer to a larger and omnipresent cultural phenomenon. This phenomenon is called “cultural additivity.” Here, storytelling, which was the medium through which a society passed on its ideas and culture (Becker and Green, 1987), offers insights into the religious beliefs and practices of the storytellers’ historical situation, and in turn, raises questions about how people can hold seemingly contradictory ideas not just back then but even nowadays. Yet, it is not simply the cognitive dissonance that this study is interested in, it is instead the seamless acceptance and continual addition of beliefs, ideas, and artefacts, which are at times conflicting, as revealed through the Bayesian framework in the following models, that would mark the findings here apart from the scholarship on hybridity and syncretism.

Literature review

Background on relevant concepts

This study uses the term “cultural additivity” that has only been mentioned once in the academic literature but not fully explored (Klug, 1973). The term describes a mechanism whereby people of a given culture are willing to incorporate into their culture the values and norms from other systems of beliefs that might or might not logically contradict with principles of their existing system of beliefs. Much of the discourse on cultural transmission has veered toward the assimilative aspect that draws a distinctive line between the minority and the dominant groups (Ziff and Rao, 1997). In this case, given the thousand years of Chinese domination over Vietnam (from 111 B.C. to A.D. 939), one could argue that the additivity phenomenon might really be a form of the Vietnamese assimilating the cultural forms and practices of the Chinese. Within this study, instead of deliberating on the Chinese influence, the focus is strictly on the simultaneous manifestations of Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist values in Vietnamese folklore. The subject adds to the already rich literature on cultural fusion and cultural transformation, especially the studies on “hybridization/hybridity,” “creolization” and “syncretism” (Grayson, 1984, 1992; Kapchan, 1993; Drell, 1999; Cohen and Toninato, 2010; Stewart, 2011). The following part will go over these concepts briefly to distinguish them from the “additivity” phenomenon.

In his essay on cultural hybridity, Ackermann (2011) gives a detailed account on the origin of the term hybridity and related concepts. From an anthropological perspective, since the second half of the nineteenth century, hybridity was used to denote the crossing of people of different races, with its usage tinged with a negative connotation of ‘‘impurity’’ (Young, 1995; Ackermann, 2011; Stockhammer, 2011). Only until the twentieth century did scholars begin to take up the concept of cultural hybridity in various disciplines, seeking to analyze the different racial and cultural contributions in colonial Brazilian society (Freyre, 1946) or the massive influx of European immigrants into the United States (Park, 1974). Post-colonial studies contributed to the re-positioning of the term hybridity as scholars argued that culture is hybrid per se given that no culture has been left untouched by the global movements of people, artefacts and information (Ackermann, 2011, p. 11).

In a synonymous way, the term creolization is often used to substitute for mixing or hybridity. Yet, historically, unlike the post-colonial interpretation of hybridity, creolization has its root in the word “creole” that dated back centuries as a way to describe people of pure Old World descent (Ackermann, 2011). It is commonly found in linguistics studies, such as the acquisition of a second language or the convergence of two languages in bilingualism. Creolization, then, involves acclimatization, indigenization and transformation (Stewart, 2011). For instance, Eriksen (2007) traces the use of this word in anthropology theory and in Mauritius, and then proposes his own definition to set this cultural phenomenon apart from hybridity or related cultural forms. His definition emphasizes the aspects of displacement, encounter and mutual influence that result in an ongoing interchange of symbols and practices (Eriksen, 2007, pp. 172–173).

By comparison, syncretism is often used in religious contexts, either to describe religious systems in which people practice two religions side by side, in an alternate or complementary manner (Ringgren, 1969; Stewart, 2011), or to mark the syncretic features of the transmission of religion from one culture to another (Grayson, 1992). There is also a host of studies exploring the concept of cultural syncretism, such as the cultural absorption of medieval Southern Italy and Sicily in the twelfth century (Drell, 1999), the cultural dissemination and incorporation of psychology and psychoanalysis in Brazil during the military period of 1964–1974 (Lenz Dunker, 2008), or the ways Goan people in India bridge the cultural differences between Hindus and Christians and thereby foster civility (Gomes, 2007), among others. Within the scholarship, it appears that the term syncretism has largely been used to describe the amalgamation of formerly discrete world views (Eriksen, 2007), or specifically, the crossing of two religions that have existed side by side for centuries, with three possibilities: repression of either one, complete fusion, or a syncretic result in which the foreign elements are deemed as essential or less essential (Ringgren, 1969). One of the more well-known studies on the diffusion of religion across cultural boundaries is by the scholar James Huntley Grayson. In his study on the acceptance of esoteric Buddhism during the Three Kingdoms era in ancient Korea, Grayson (1984) defines religious syncretism as “a cultural process that may be understood as one part of the broader process of cultural diffusion.” He categorizes the concept into high and low syncretism to reflect the level of changes in the core set of values of the missionary religion when in contact with the indigenous religion.

For this study, Grayson’s conceptualization of high syncretism, or reverse syncretism, is most relevant as it encompasses the accommodation of an indigenous religion—here the Vietnamese folk belief—to the beliefs and practices of foreign religions—such as the three teachings or religions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. At the same time, Brook (1993) makes a valid point on not letting the concept of syncretism “monopolize the full range of possible mixings that occur between distinct religions in a religiously plural society.” When looking at the joint worship of the three Teachings in late imperial China, Brook argues that syncretism, which implies reconciliation of even contradictions, rarely happens because it is hard for elements of distinct world views to resolve or reconcile their dissonance naturally.

Keeping in mind the overlapping ideas, this study employs a different term, “cultural additivity,” in examining Vietnamese folklore and culture at large, mainly because the existing concepts are loaded with either historical or religious meanings, as explored above and summarized in Table 1.

For instance, one study on post-colonialism in Vietnam points out the different forms of hybridity within its society, such as a hybrid modernity born out of the colonial and socialist modernities (Raffin, 2008). It is indeed necessary to look beyond the colonial residues, i.e., the French influences, to places such as China, the Soviet Union, the U.S. or from within itself in order to build an appropriate framework for grasping both the local folk and contemporary culture. With these considerations in mind, the term “additivity,” which simply means the adding of different ideas, beliefs, artefacts into one’s existing system whether or not there is reconciliation of contradictions, would offer a neutral starting point for understanding certain cultural phenomena in Vietnam and elsewhere. As such, the concept is distinctive from the other three concepts because it does not imply any sense of cognitive dissonance, but rather describes the adding of even conflicting beliefs in an arbitrary manner.

Hybridity, syncretism in folklore studies

To understand the Vietnamese cultural behaviours through an analysis of local folktales, it is important to review how the aforementioned concepts have been featured in folkloristics.

Kapchan (1993) notes the introduction of the marketplace as a metaphor weighted with history and economic paradigm in folklore studies, suggesting that attention to the hybrid transformations in the expressive economy, i.e., the marketplace, could help us identify our social direction. In another study, Bronner (2005) delves into the creolization and hybridization in European and American folklore studies in its formative period in the nineteenth century. Here, Bronner looks at the movement toward modern folklore, such as the belief in a unilinear progress model that prioritizes racial purity and superiority and the heterogeneous model that attaches social and historical conditions to cultural behavior. Through the scholarship of American academic folklorist Lafcadio Hearn, the author finds that the theory of hybridization not only helps normalize racial hybridity or the issue of race in modern folklore, it also expresses the multiculturalism in America at the time. In a more recent book, the anthropology and religion scholar Magliocco (2010) offers insights into the way North American Neo-Pagans use folklore, or traditional expressive culture, to establish identity and create a new religious culture. She points out that the exposure to globalization on the North American continent, particularly the United States, has resulted in new kinds of hybridity and cultural mixing.

Other folkloristics studies have notably pointed out the role of storytelling in accommodating new ideas or beliefs, some of which may be conflicting with the existing cultural or religious system. For instance, narratives of ghosts and spirits in nineteenth century Estonian folklore are said to contradict the doctrines of the Church about death and the dead (Valk, 2012). Similarly, the folk beliefs of the Yoruba people, an ethnic group from West Africa, also exhibit major contradictions concerning the posthumous life. An example of this is the impression of the late ancestors living in the sky in its popular folktales, even if the dead are known to be buried underground and have transitioned to the “ghostland” (Olomola, 1988). In Asia, the Korean variants of the folktale Cinderella (AaTh 510) (Cox, 1893) are also shown to have accommodated the co-existence of Confucian ideology (filial devotion), Buddhist teachings (devotion to Buddha, reincarnations), and indigenous Korean beliefs (appeals to heaven) (Tangherlini, 1994). In this Korean version, there is a conflict of essential motifs with the religious beliefs, primarily Buddhist, such as the reincarnation of the mother, a good person, as a cow even though reincarnation as an animal reflects one’s poor karma. Valk (2012) argues that the interdependent co-existence of various discourses in folklore can be understood as a dialogue with “an inherently contradictory and incoherent web of beliefs and genres in constant fluctuation.” The different viewpoints and opinions, thus, co-exist in intertextual relationships and even clash against one another without repressing the alternative voices (Valk, 2012).

The Three Teachings/Religions in Vietnam

To understand how this study was carried out, it is imperative to be acquainted with the Three Religions or Teachings in general and in Vietnam in particular.

First, one should note that the Vietnamese language lacks the exact equivalent to the Latin word religio, which could be interpreted as either reread or more commonly, as a combination of re- and ligare (to bind) to create the meaning of reconnection or relation (Durkheim, 1897). The word “religion” (tôn giáo) in Vietnamese, which is a direct translation from Chinese (宗教), could mean “way” (đạo 道) in common speech or “teaching” (giáo 教) in scholarly writings (Tran, 2017). Vietnam has its own popular religion which is characterized by the worshiping of ancestors, historical heroes, local deities and goddesses, local festivals honoring village gods, various forms of exorcism of harmful forces, spirit-possession, the practices of divinations; the offering to deities, goddesses, even the Buddha for luck (Cleary, 1991; Toan-Anh, 2005; Kendall, 2011; Tran, 2017). What is interesting is, despite these practices and rituals, many Vietnamese people declare to “have no religion” on their government ID cards (Hoskins and Ninh, 2017).

Second, the relative religious pluralism in Vietnam, sprouted from the Chinese concept of “Three Religions with the same root” (“tam giáo đồng nguyên” 三敎同源), likely took shape during the Lý-Trần dynasties (1009–1400) (Nguyen, 2013). The concept is widely understood as the co-existence, convergence and even unification of the three religions in Vietnam (Le, 2016). However, some scholars have suggested that among the three, Taoism, with its emphasis on avoiding conflicts and retreat to isolation, is less influential in Vietnamese society (Nguyen, 2013; Xu, 2002) and often manifested in the shamanic practices such as “masters of the amulets” (thầy bùa), “magician healers” (thầy pháp), or “soothsayers” (thầy bói) (Tran, 2017). By comparison, Buddhism caters to the spiritual aspect of the population while Confucianism serves as a moral basis for political and institutional organizations (Nguyen, 2014c). The core teachings of the three religions are presented below.

Buddhism

On the history of Buddhism in Vietnam, a number of scholars have traced its introduction back to the first or second century A.D., with historical evidence suggesting its first-hand entry from India rather than through China (Nguyen, 1985; Nguyen, 1993; Nguyen, 1998; Nguyen, 2008; Nguyen, 2014d). The third century marked the construction of the first Buddhist temples and the origin of the earliest stories of Buddhism in ancient Vietnam, which have a Sinitic Buddhist vocabulary but are plausibly linked to South Indian Hinduism (Taylor, 2018). Over the next centuries, Buddhism continued to spread in Vietnam thanks to the contributions of Indian, Central Asian, Chinese, and even Vietnamese monks who had studied Buddhism in India or China (Nguyen, 2008, p. 19).

In terms of its teachings, Vietnamese Buddhism is characteristic of Buddhism in China, Korea and Japan, populated with several schools of thoughts including Zen, Pure Land, and Tantra (Cleary, 1991). In this sense, the core beliefs and teachings of Buddhism as they are known and practiced in Vietnam also revolve around these concepts: The Four Noble Truths, the Eight-fold Path, karma, and reincarnations. This part provides a brief introduction to these concepts in order to lay the context for the study.

The Buddha, when giving a diagnosis of life predicament, has come up with Four Noble Truths: (i) life is dukkha (usually translated as “suffering” or “dissatisfaction”), (ii) all sufferings are caused by tanha (usually translated as “desire” or “craving”), (iii) when one ceases to have all these desires and cravings, his/her sufferings will cease; and (iv) finally, Buddhism offers the escape path out of this predicament through the Eight-fold Path: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concertation (Smith and Novak, 2004, pp. 31–49; Gethin, 1998, pp. 59–79).

Among the core ideas of Buddhism that have permeated the Vietnamese culture, the concept of karma (nghiệp) is the most ubiquitous. Karma refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect where intentions and actions of a person (cause) will affect his future outcomes (effects). This concept is related to that of reincarnation, because one’s karma will determine one’s fate in the next life. A closely relevant idea in Vietnam is duyên (yuan-缘), which is equivalent to the Sanskrit word pratityasamutpada and is translated into English as “dependent origination” or “conditionality” (Hoang, 2017).

Confucianism

The introduction and absorption of Confucianism into Vietnam also took place over centuries. According to Nguyen (1998), Confucianism was introduced to Vietnam during the Chinese domination from 111 B.C. until A.D. 938 due to a policy of assimilation, which successfully transformed the Viet society from a matriarchal system into a patriarchal one. It was the Buddhist monks, the most learned men at the time, who not only spread their religious beliefs, but also taught Confucianist philosophy to the Vietnamese people seeking a civil servant post (Nguyen, 1998, p. 93). When Confucianism gained more followers in the eleventh century, Confucian scholars were said to have opposed Buddhism. The spread of Neo-Confucianism in Vietnam began during the Lê dynasty (1428–1788), continued through the eighteenth century, and reached its peak influence under the Nguyễn dynasty (1802–1945).

Given such historical depth, Confucianism has become more about a way of life than a religion in the Vietnamese culture (Nguyen, 1985). Although there might have been some Vietnamese adaptation or “Vietnamization” of Confucianism in Vietnam (Nguyen, 2015), the basic teachings on the moral codes, manners, and etiquettes for living harmoniously in a moral society remain close to the original Confucianism in the Vietnamese mind. These core virtues are summarized in Table 2.

Notably, “righteousness” or (nghĩa 義) is mentioned in two sets of virtues. In many contexts, this word often goes with chastity or purity (tiết 節) to denote the responsibilities of the husband, in reciprocation to his wife’s devotion (Như-Quỳnh and Schafer, 1988). It could also have other meanings; when appeared together with benevolence (nhân 仁), “nghĩa” could denote a principle of high moral conduct. This meaning was also well-known and could be found in common Vietnamese sayings, namely “Respect righteousness, despise riches” (Trọng nghĩa khinh tài), which encourages people to do the right thing, not in the hope for some material reward (Như-Quỳnh and Schafer, 1988).

Confucianism was not only about social order; it also laid the foundations for institutions of governance in Vietnam, namely the selection of imperial officials through competitive exams based on Confucian teachings. This aspect still rings true in contemporary Vietnamese culture. For example, the educational system, business practices, and even the law in Vietnam are often described as being heavily influenced by Confucianism (Pham, 2005; Pham and Fry, 2004; Vuong and Tran, 2009; Vuong and Napier, 2015).

Taoism

The earliest appearance of Taoism or Daoism in Vietnam dated back to the second century when some Taoist monks from China sought to spread their ideas to the area that is now northern Vietnam (Xu, 2002). Xu cites historical records as noting that Taoism in Vietnam developed the most strongly during the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907) and later continued to exert a huge influence on the Vietnamese Lý and Trần dynasties (1010–1400).

There were two ways to interpret Taoism: the philosophical Taoism (Đạo gia) and the religious Taoism (Đạo giáo). Based on the classics Daodejing of Laozi and Huainaizi, the philosophical Taoism offered a worldview based on the natural approach to life. Vietnamese people were introduced to this philosophy through concepts such as dao, the yin and yang, the Five elements, the ethics of “non-contrivance” or “effortless action” (vô vi or wuwei 无为) (Slingerland, 2003) and “spontaneity” (tự nhiên 自然). The way of life in philosophical Taoism was largely aimed towards reaching the wuwei realm. The word wuwei means doing nothing in the sense of letting life flow naturally. Nature was the leitmotif of the Taoist philosophy and truly set Taoism apart from Confucianism (Novak, 1987). Consequently, the image ideal of a person who retreats to the nature and free from the constricted life of Confucian rules is usually associated with Taoism.

Religious Taoism, like Buddhism, does not have a core system of specific teachings. Broadly speaking, its practices focus on the search for longevity and immortality, spiritual healing, magic, and divinations, which blended in with Vietnamese popular religious beliefs (Tran, 2017, p. 13). Unlike in China, Taoism in Vietnam took no institutional form, in the sense that there were no Taoist schools. Practitioners of Taoism, called “masters” (thầy) were often shaman-like specialists in a variety of domains such as healing, ritual sacrifice (at funerals, for example), soothsaying, sorcery, geomancy, etc., and were often not attached to any temple. In fact, Taoist temples did not serve the role of training monks and priests; rather, they were places of worship for immortals (historical figures who had been ‘‘canonized’’ in Vietnamese culture and folk beliefs) and Taoist deities such as the Jade Emperor (Ngọc Hoàng). The Vietnamese Taoist pantheon was widely accepted by the population, to the point that they weren’t recognized as Taoist deities anymore, rather simply considered as traditionally worshipped gods. Due to its shamanistic and ritualistic nature, which is more commonly associated with ethnic minorities, Taoism often appears in a less “official” light than Buddhism and Confucianism and, at times, could even risk being reduced to the status of “superstitions” (Kendall, 2008). However, the closeness of Taoism to nature makes it blend with the most ease to Vietnamese traditional beliefs and ancient traditions such as the Mother Goddess Religion (Đạo Mẫu) or the Religion of the Four Palaces (Tứ Phủ), all of which are rooted in natural forces (Kendall et al., 2008). In this manner, despite not having as prominent a presence as the other two major religions of Vietnam, Taoism is in a favorable position to spread as a popular religion.

Methods

Research question

RQ: How does the Bayesian method of analysis help discover the additivity underlying in hundreds of tales whose core messages are categorized as Confucian, Buddhist, or Taoist?

Study design

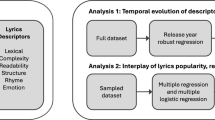

The design of the study is summarized in Fig. 1.

The procedure of data collection and analysis in this study. First, based on the observations of Vietnamese folktales, the Three Teachings/Religions and other cultural phenomena, the study is conceptualized. Then, team members are trained in the relevant literature related to the Three Teachings/Religions to understand the variables and then to input the data. The resulting dataset is cross-checked before being analyzed with the Bayesian method, which finally leads to the concept of cultural additivity

As shown in Fig. 1, the study is conceptualized based on the understanding of Vietnamese folktales and the Three Teachings/Religions, the observations of various cultural phenomena in Vietnam such as the idea of ‘‘invented culinary heritage’’ (Avieli, 2013), the acute problem of forgery in arts (Vuong et al., 2018a), the Franco-Chinese architecture, the rampant plagiarism in education (Vuong, 2018; Do Ba et al., 2017), economics, etc. Then, choosing folktales as the raw materials for the study, variables are constructed to help datafy each story. Team members of the study are trained with the relevant literature on the Three Teachings/Religions to understand the variables and to input the data correctly. During the process of data inputting, cross-checking among members of the team and random checks are carried out to ensure the validity of the data. The dataset is then analyzed with the Bayesian method, which confirms the presence of the “cultural additivity” phenomenon. This procedure is inspired by the data organization laid out in the data descriptors in Nature Research (Vuong, 2017a; Vuong et al., 2018d; Vuong et al., 2018b). All the data are presented openly at Open Science Framework and Harvard Dataverse, according to the principle of open data and scientific transparency (Vuong, 2017b; D’Oca and Hrynaszkiewicz, 2015), and FAIR principles (Wilkinson et al., 2016).

Materials

Within the first months of 2018, the study had collected 345 lines of data as the results of reading and analyzing 307 different stories from six major sources, as summarized in Table 3.

The study sources 88% of its materials from the collection of Vietnamese folktales that were either collected and rewritten by (Nguyen, 2014a, b), or posted online at a number of popular domains. The work by (Nguyen, 2014a, b) is arguably one of Vietnam’s most systematic folktale collections as it touches on the characteristics, origins, and historical development of Vietnamese folklore as well as provides variants of folkloric motifs in the folklore of other countries and ethnicities (On, 2016).

The other major collections of stories are known in the Vietnamese language as truyền kỳ, a term that originated from the Chinese word 传奇 (narration of strange things). These collections are dated from the fourteenth century to sixteenth century, with some stories added as late as the eighteenth or nineteenth century. This was a period when the three religions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism rivaled each other and exerted different degrees of influence in Vietnam (Nguyen, 1998, p. 95). In his comprehensive book on the history of Buddhism in Vietnam, Nguyen (2008) notes that Confucianism only entered the domain of learning in 1075 and triumphed over Buddhism under the Lê dynasty in the fifteenth century. An example of this is the construction of the “Temple of Literature” (Quốc Tử Giám/ Văn Miếu) as a school dedicated to Confucianism in 1070. The collections of tales were likely recorded by Confucian scholars serving Vietnamese courts over the centuries. While this may look as though Taoism in Vietnam was not as influential, it is important to remember that, with its shamanic elements and ornate rituals and worshiping, Taoism was equally popular from 1010 to 1400 (Xu, 2002). Such influence has manifested in the narratives about “spiritual powers,” “extraordinary beings,” and “strange tales.”

Conceptual model for measuring cultural additivity

With this approach to Vietnamese folktales, the team members then analyzed the co-existence of Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, and the possible interaction among the three religions in influencing folk mentality. The diagram in Fig. 1 presents the logic of the model.

Fig. 2a is a simple model with no cultural additivity: the story conveys a key message dominated by only Confucianism. This fact is predicted through the appearance of the values and anti-values of said religion. For instance, in the “Tale of the Bundle of Chopsticks,” (Nguyen, 2014a) a father wanted to teach his two sons, who were always quarreling, by telling them to try and break a bundle of chopsticks. The sons tried with all their strength to break the bundle but failed; then the father took out the bundle and broke the sticks one by one. His action illustrated the importance of uniting, that being united gives strength while being divided could hurt. The message is Confucian in essence for its emphasis on solidarity and harmony within the family. The story marks no other magical or religious intervention, and thus, falls under the first model of simple reflection with no additivity. Fig. 2b is a complex model of cultural additivity. In this model, whether Confucianism dominates the key message of a story is predicted through the appearance of its values multiplied by the probability of appearance of the values and anti-values of other religions. Fig. 2c is a simple model of cultural additivity: the probability that Confucianism dominates the key message of a story is determined by the appearance of its values and anti-values, as well as the appearance of the values of other religions (Refer to the Supplementary Information file for the figures that represent the cultural additivity models of Buddhism and Taoism).

The “cultural additivity” is measured by two types of variables in binary value (1 for yes and 0 for no): the dependent variables which categorize the stories and its central messages in accordance with the three religions, and the independent variables which categorize the attitude and behavior of the main characters (both protagonists and antagonists) within the stories also according to the three religions. The logic of Fig. 2 is captured in a set of three logistic equations:

Models series for Confucianism or C contains equations (mC1-3):

C~Binomial(1,p) (mC1)

logit(p) = αC + β{VC}⋅VC + β{AVC}⋅AVC

αC~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VC}~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VAC}~Normal(μ,σ)

C~Binomial(1,p) (mC2)

logit(p) = αC + (β{VC} + β{VB}⋅VB + β{VT}⋅VT)⋅VC + β{AVB}⋅AVC

αC~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VB}~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VC}~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VT}~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VAC}~Normal(μ,σ)

C~Binomial(1,p) (mC3)

logit(p) = αC + (β{VB}⋅VB + β{VC}⋅VC + β{VT}⋅VT) + β{AVC}⋅AVC

αC~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VB}~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VC}~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VT}~Normal(μ,σ)

β{VAC}~Normal(μ,σ)

Refer to the Supplementary file for the equations for Buddhism (mB1-3) and Taoism (mT1-3).

Dataset construction

As a general rule, each story corresponds to one line of data when the ending of a story is predominantly about one character or a group of similar characters. However, a story may have more than one character with very different endings, entailing more than one line of data input. For example, in the Vietnamese version of Cinderella, known as “Tam Cam Fairytale,” (Nguyen, 2014a) the protagonist Tam and antagonist Cam each have one line of data because of their different characteristics and storylines. This story embraces Confucian morality (loyal to the king, pious to the parents, or virtuous as a wife), shows the people’s veneration for an almighty figure possibly derived from Buddhism but having Taoist magical power, and also emphasizes the Buddhist “karma” or law of moral causation. Given the presence of these elements, in our data master file, all columns indicating the values and anti-values of Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism were ticked 1. Table 4 describes how the folktales are coded.

There can indeed be confusion in following the variables description. For example, certain values or anti-values can show up in two or all religions such as self-cultivation (which can be a value of all three religions) or cruelty of a husband toward his wife (which can be either anti-Confucian or anti-Buddhist). Here, it is important to consider the wider context in which these actions/attitudes take place. For example, if self-cultivation is about accumulating good karma, then VB = 1; if self-cultivation is about performing rituals (lễ 禮) to become a Confucian gentleman (quân tử 君子), then VC = 1; if self-cultivation is about achieving wuwei (vô vi), then VT = 1. Similarly, if cruelty of a husband toward his wife is situated in the context of the violation of the Three Moral Bonds (tam cương 三 綱), then AVC = 1 and AVB = 0.

As a general rule, to determine which religion’s values a particular action or attitude characterizes, it is necessary to first determine which religion dominates the central messages of a story (the values of C, V, B) before considering whether the story has other religions’ elements. For example, a Buddhist tale (B = 1) can have Taoist and/or Confucianist elements (VT/AVT = 1 or VC/AVC = 1). This is to prevent the arbitrary coding.

The logistic models work here because all variables are dichotomous and the data for response and predictor variables are discrete, enabling a prediction of the probability of each value of the dependent variable given specific values of the independent variables (McElreath, 2016). The files were deposited with the open code principles at Open Science Framework. Here is an example of the Stan codes:

data{

int<lower = 1 > N;

int T[N];

int VB[N];

int VT[N];

int VC[N];

int AVT[N];

}

parameters{

real a;

real bVC;

real bVB;

real bVT;

real bAVT;

}

model{

vector[N] lp;

bAVT~normal (0, 10);

bVT~normal (0, 10);

bVB~normal (0, 10);

bVC~normal (0, 10);

a~normal (0, 10);

for (i in 1:N) {

lp[i]=a+(bVT * VT[i] + bVB * VB[i] + bVC * VC[i]) + bAVT * AVT[i];

}

T~binomial_logit (1, lp);

}

generated quantities{

vector[N] lp;

real dev;

dev=0;

for (i in 1:N) {

lp[i]= a+(bVT * VT[i] + bVB * VB[i] + bVC * VC[i]) + bAVT * AVT[i];

}

dev=dev + (−2)*binomial_logit_lpmf (T | 1, lp);

}

Another example of R commands to run Stan codes was deposited in the R file “est_stan_180226_v5.R”. The computer codes in this file employed a combination of utility programmes called from the R file: “DBDA2E-utilities.R”, programmes used with the book Doing Bayesian Data Analysis, Second Edition (Kruschke, 2015).

The results of estimations using the above codes were also tested with the “Rethinking Package” v1.59 of Richard McElreath (URL: https://github.com/rmcelreath/rethinking) (McElreath, 2016). Other programmes to run estimations for each model in the aforementioned series were packaged in the R file: “20180226b_rethinking_map.R”. The estimation had in total 8000 iterations, divided into 4 Markov chains, each containing 1000 warmup iterations. Here is an example of the codes:

mT.3 <- map2stan (alist (T ~ dbinom (1, lp), logit(lp) <- a+(bVT*VT+bVB*VB + bVC*VC)+bAVT*AVT, a~dnorm(0,10), bVC~dnorm(0,10), bVB~dnorm(0,10), bVT~dnorm(0,10), bAVT ~dnorm(0,10)), chains=4, data = dat)

In order to check the robustness of the models through prior and to create a visual presentation of the test, the team has used Rethinking Package in R. The categorical regression for the dichotomous predicted and predictor variables was carried out thanks to the computing power of Stan’s Hamiltonian MCMC in the statistical software R (release 3.3.3). We performed this regression both directly and using Stan codes for files named mB1.stan, mB2.stan, mB3.stan, mC1.stan, mC1.stan, mC2.stan, mC3.stan, mT1.stan, mT2.stan and mT3.stan.

Results

Bayesian inference of the estimation results

As one of the main criteria for judging a preferred model for its goodness of fit is the “weight” in the Bayesian statistical method (McElreath, 2016), the distribution of weight is indicative of the credibility of the model, thus comparing the weight across models can help us eliminate results that are not supported by evidences. After choosing the most credible models for further analysis, the study will look at the final results in form of mathematical equations (See further details in the Supplementary file and the openly deposited files mentioned in the Data Availability).

Here, the characterization of Kruschke (2015, p. 15) is useful: “Bayesian data analysis has two foundational ideas. The first idea is that Bayesian inference is reallocation of credibility across possibilities. The second foundational idea is that the possibilities, over which we allocate credibility, are parameter values in meaningful mathematical models.”

First, according to Table 5, among all model series for the three religions, only the model series for Confucianism show clearly the property of additivity, and both simple (mC3) and complex (mC2) models of additivity show that the existence of additivity is credible. This finding is reached by first comparing the weight of the three models of Confucianism where (mC1)/(mC2)/(mC3) = 44/41/16, as shown in Table 4 above. It seems obvious that the appearances of (anti-) Confucian values (abbreviated as VC or AVC) should be associated with whether the key messages of a story were about Confucianism. Yet, after running the statistical test through 345 lines of data, it is surprising that the weight of simple (mC3) and complex additivity of Confucianism (mC2) is not too far off from the obvious (mC1). Here, though only with 16% weight, the complex additivity model (mC2), the most counter-intuitive one, does have the potential influence and the explanatory strength.

For Buddhism, the phenomenon of additivity can also be inferred with reservation as the model of complex additivity (mB2) and simple additivity (mB3) have 20% and 12% weight, respectively. However, compared with the dominance figure of 68% of (mB1), clearly, it is more appropriate to infer the low additivity of Buddhism.

For Taoism, the pattern is different as the model of no additivity (mT1) has 52% weight and the model of simple additivity (mT3) has 40% weight, while (mT2) has only 8%. There seems to be some credibility in the model of simple additivity of Taoism. However, when the coefficients resulted from the models are examined, the evidence is not clear.

As Table 6 shows, in the simple model of (mT3), the coefficients and MCMC statistical estimations show that the factor with the strongest influence is of Taoist values, β{VT} = 3.96; next is the coefficient of anti-value of Taoism, β{AVT} = 2.44. Both numbers illustrate two purely Taoist elements. Meanwhile, the additivity of Confucian values is also confirmed but the coefficient β{VC} is negative (−). This means the existence of Confucian values reduces the influence of Taoist values. The effect of Buddhist values could not be confirmed because though β{VB} is negative (−), it deviates too widely to the two sides of zero (see Table B in the Supplementary file).

A closer look at the (mB2) model, i.e., a complex additivity model of Buddhism, reveals that factors with the strongest influence are β{VB} = 2.52 and β{VAB} = .91, while the β{VB.VC} and β{VB.VT} take on much lower values, 0.69 and 0.44 respectively. The results highlight the low additivity property of Buddhism in Vietnamese folktales.

In the case of (mC2) and (mC3), the strongest coefficients of the two models are β{VC} with respective values of 2.94 and 3.11 for (mC2) and (mC3). This is basically the same in terms of probability, as logistic (2.94) = 95% is comparable to logistic (3.11) = 95.7%. The second highest coefficient belongs to anti-Confucian-values elements, with β{AVC} valued at 2.19 in both equations.

The most interesting result is that the appearance of Taoist elements take on the coefficient values of β{VT.VC} =0.86 in (mC2) and β{VT}=0.73 in (mC3), respectively. Although, technically speaking, the simple additivity model (mC3) is more weighted, one might be more drawn toward the complex additivity model (mC2) as the co-existence and interaction with Confucian elements in the stories are stronger with β{VT} > 0. The coefficient reflects the existence of predictor VT.VC in the equation of (mC2).

As can be seen from the equation, this interaction among elements of Confucianism and Taoism together increases the probability of categorizing a story into the C category: it conveys key messages about Confucianism. On the one hand, this model reflects the logic in thinking about cultural influence and interaction, which had launched this statistical investigation. On the other hand, this is the only evidence of significant additivity among religious values in folktales among all the estimated models.

Robustness check on the sensitivity to the prior

Here, it is important to take a small detour to look at the robustness check of (mC3)’s Eq. 3’s sensitivity to the prior, one of many methods of evaluating the evidence offered by the Bayesian method (Quintana and Williams, 2018; McElreath, 2016). The results could be viewed in Fig. 3. Three lines represent the posterior distribution for β{VC}. A curve shows the basic MCMC estimation, using Normal (μ = 0, σ = 10) in all estimations; in which σ = 10 indicates there is no strong belief before estimation, at the same time, μ = 0. The estimated coefficient is β{VC} = 3.11.

The visualization of the robustness check for the sensitivity to the prior of the estimation results of model (mC3) or Eq.3. a When the prior is set to widely different levels, the estimate fluctuates around 0.3, indicating robustness. b Further MCMC technical validations are performed and the results are satisfactory

When testing by lowering the strength of the belief through increasing σ = 50, MCMC estimation’s result is not much different; the two blue lines are almost completely overlapped. In contrast, when testing the model with a level of strong belief in denying altogether the coefficient’s validity, by choosing μ = −3, and strongly regularizing the prior for the parameter of standard deviation, σ = 1, the result is β{VC} = 2.55.

However, when translated into probability, the difference with the initial estimate (β{VC} = 3.11) is again very small: logistic (2.55) = 92.8% compared with logistic (3.11) = 95.7%. Indeed, the estimated standard deviation fluctuates around 0.3 even though in the prior-tests, the σ is chosen quite “wildly”: σ = {1, 10, 50}. This is a stark indication of robustness. In addition, we perform the MCMC technical validation for these estimations, which is exhibited in Fig. 3b. In general, all the technical properties meet the requirements, even when the length of the Markov chain is not increased. Four posterior distributions showed a standard shape and almost completely overlapped (the bottom right of Fig. 3b).

In our observation, an arbitrary coding of the folktales would lead to chaos in finding Bayesian evidence, and eventually the lack of robustness of the Bayesian inference. However, other sensitivity analyses show a similar pattern: the major changes in prior do not lead to any considerable change in the final results, which demonstrates the models are robust. The codes are presented in the Supplementary file and the visualization of the results of those tests are deposited in OSF (For further discussion of the technical aspects, see (Vuong et al., 2018c).

Interpretation of the results

Through the Bayesian categorical analysis, the study has confirmed the existence of the cultural additivity phenomenon. The empirical results suggest an isolation of Buddhism and a higher possibility of additivity where a story concerns Confucianism and Taoism. It also shows that the interaction or addition of Confucian and Taoist values in folktales together help predict whether the key message of a story is Confucian. For Buddhism and Taoism, there is no such statistical confirmation. This result could be interpreted as the dominance of Confucianism over the two other religions. The interpretation is attributable to two reasons: (i) the folktale collections were likely recorded by Confucian scholars of the time (as discussed in the Materials sub-section), and (ii) the history that Vietnamese Confucianism gained enough followers to expand without the help of Buddhist monks and later came to oppose Buddhism in the twelfth-thirteenth centuries onwards) (Nguyen, 1998, pp. 94–95; Nguyen, 2008). In other words, as Confucian scholars rose to power in the courts and expressed their hostility towards Buddhism, it is possible that these scholars had intentionally left out stories with messages about Buddhist values or virtues. As for how Confucianism and Taoism accompany each other in stories whose central message is Confucian, because Taoism in Vietnam does not take institutional forms (Tran, 2017; Xu, 2002), there is little power struggle between these two religions.

This interpretation leads to a broader understanding that the phenomenon of cultural additivity—defined as the arbitrary tolerance of and willingness to add new beliefs, values or norms even when there was contradiction, to the existing system of belief—might be limited to cases where the two religions in interaction were not too far away or competing in terms of values. For example, Confucian and Taoist values seem contradictory. Confucianism upholds a rigid hierarchy and equally rigid rules of conducts in different social context as well as moral obligations to study and become a member of the court, to be involved with the movement of the nation, of the society. The wuwei life of Taoism is almost the complete opposite: to retreat to isolation, to live closer to nature, to consider all concerns left behind as mundane, even though many of such concerns would have been obligations in Confucian principles. However, in a way, it was possible to adhere to both Confucianism and Taoism. Concretely speaking, this means that after living the pragmatic life and restrictive path to virtue and honor prescribed by Confucianism, one could seek comfort in the isolation in nature offered by Taoism. In fact, one could even imagine that a person who has followed all this constricted life of Confucianism would, later in life, desire the Taoist ideals. A typical example might be the Giong character in the tale of “Heavenly King Phu Dong” (Phù Đổng Thiên Vương): he helped the king fight against invaders, exemplifying the Confucian trait of loyalty, but in the end decided to “retreat” by flying back to Heaven, essentially representing a Taoist ideal. As for the isolation of Buddhism, the path of non-attachment, of “phổ độ chúng sinh” (to bring compassion to everyone), of self-cultivation with the practices of the Eight-fold way might be too demanding, thus the values and norms put forth by Buddhism might be too far away to be added together with the other two religions.

Discussion

Technical implications

The research confirms the thorough theoretical works on syncretism—an important concept that has become a cornerstone in understanding culture and religion (Ringgren, 1969; Stewart, 2011; Grayson, 1992). However, in light of the rising complexity of modern societies, the problem is operationalizing such concepts to best reflect the changing landscape as well as to continue represent the cultural core pointed out by syncretism. This study offers one step further, proposing the use of a new concept called “cultural additivity” after running a new technical analysis method on conventional resources such as folktales. The estimations and figures were the results of employing an analytical tool that is philosophical and robust like Bayesian statistics (Kruschke, 2015; McElreath, 2016; Bunce and McElreath, 2018). The combination of a modern analytical method and a big volume of folktale data, the kind that is almost timeless, helps strengthen previous efforts in theorizing concepts, and paves the way for the future conceptualization of similar concepts or phenomena.

With this consideration in mind, the study suggests viewing the concept of “cultural additivity” as an extension of syncretism, hybridity and creolization in a technical dimension. This new term is useful in the sense that it is free from the historical and contextual biases as well as is supported by empirical evidence. Here, the Bayesian technique helps minimize an arbitrary coding, which if not controlled would lead to chaos in finding Bayesian evidence and eventually the lack of robustness of the coefficients (See the details of the robustness test in the Supplementary file and the files deposited in OSF).

Societal implications

Up to this point, some scholars have implied that either all three religions Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism are on an equal footing, per the “Three religions with the same root” principle (Le, 2016; Nguyen, 2013), or Taoism is slightly dwarfed by the other two in terms of influence on society (Xu, 2002). However, the empirical results in this study have challenged these views. While it might be true to claim that the three religions co-exist in a cultural entity, the empirical results allow us to make the case that there is more than just mere co-existence. There is indeed complex interaction and, seemingly, a domination of Confucianism over other religions.

While there may in fact be no unity of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, Blagov (2001) notes that religious amalgam is universal among the Vietnamese, which allows for the rise of Caodaism (“Đạo Cao Đài”) in the 19th century. Caodaism, founded in 1926, brings together elements of the East and the West by worshipping Buddha, Lao Tzu, Victor Hugo, Confucius, Jesus Christ, etc. (Hitchcox, 1990; Quinn-Judge, 2013), and even considers the Jade Emperor (Ngọc Hoàng) and the Holy Spirit to be one (Louass, 2015; Hoskins, 2012; 2015). The religion, with its deep roots in Sino-Vietnamese tradition (Smith, 1970), has largely been looked at through the lens of syncretism. The concept of “cultural additivity” may also be helpful in the discussion on the essence of Caodaism. For example, it allows us to look at the addition of all the elements that constituted this religion without having to reconcile their differences: the founder of Caodaism, Ngo Van Chieu (1878–1932), grew up in a Confucian family to become a bureaucrat in French Cochinchina, and was even said to have abided by Taoist doctrines strictly in a very solitary life (Smith, 1970; Blagov, 2001).

Going beyond the religious realm, one could observe that this tendency to add selected elements of other religions into the existing system of norms and beliefs can also be found in the incorporation of colonial French (columns and windows), Confucianism (the scroll), and Buddhism (the lotus) in the façade of a house in the Old Quarters of Hanoi (see Fig. 4).

Another example is that Vietnamese traditions today originated from Buddhism-folk beliefs, some of which have given rise to superstitious rituals of unconfirmed origins. For instance, the burning of ghost money and goods for the dead, falsely attributed to Buddhism (Xuan, 2018), is regarded as a way for the living to either relieve the suffering of the dead, especially those who had died in grievous circumstances (Kwon, 2007), or to communicate, even negotiate, with supernatural forces (Seth, 2013; Kendall, 2011). It appears the cultural additivity as seen among the Vietnamese people might be the reason behind the country’s quick and flexible adoption of, and adaptation to, new ideas, be it religions, languages, or even ideology.

Limitations and future research directions

Through the statistical analysis, the study highlights the efficiency of Bayesian statistics in quantitatively analyzing a cultural phenomenon (“cultural additivity”) using traditionally qualitative materials, i.e., Vietnamese folkloric literature. This method adds to the exploration of using texts as social and cultural data explored in previous work of computational folkloristics and sociolinguistics (Nguyen, 2017; Bortolini et al., 2017a; Tehrani and d’Huy, 2017; Abello et al., 2012; Tangherlini, 2013; Da Silva and Tehrani, 2016; Youngblood and Lahti, 2018). However, similar to the shortcomings of other computational works of folktales (Tehrani and d’Huy, 2017), the coding of the dataset in this study is determined by an individual researcher. Therefore, the dataset and results will always be at risk of being influenced by personal biases. To mitigate this risk, one solution would be to compare analyses based on other datasets with different coding methods or to reconstruct the dataset using the same coding method.

As this study presents a method of encoding the values and practices of the Three Great Religions in East Asia in text, it is then important to devise more generalizable methods that can be applied (i) for other nations influenced by the religions, (ii) across other areas of culture and media studies, (iii) and for more universal frameworks of understanding morality such as the Moral Foundations Theory (Graham et al., 2011) or Cultural Dimensions theory (Hofstede and Bond, 1984). Analyzing the datasets using a modern statistical technique such as Bayesian statistics could yield valuable behavioural and cultural insights and help advance social sciences and humanities into a more interdisciplinary (Pedersen, 2016) and reproducible direction (D’Oca and Hrynaszkiewicz, 2015; Munafò et al., 2017).

Conclusion

This interdisciplinary study is among the first attempts to quantitatively mining the insights on the behavioural patterns in hundreds of Vietnamese folktales using the Bayesian method. This approach has presented a new method to encoding values and practices of the Three Great Religions in East Asia, i.e., Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, in folktales into binary values. Thus, it adds to the scholarship on computational folkloristics in general and on country-focused folklore studies in particular. The empirical results, illustrated in the three models of additivity, confirm the existence of the discussed phenomenon: not only is there an isolation of Buddhism in the folktales, there is also a higher possibility of interaction or addition of Confucian and Taoist values even when these two religions hold different value systems. This phenomenon of cultural additivity is then shown to have far-reaching societal and scientific implications.

For closing these important socio-cultural remarks after lengthy discussions on Vietnamese folk beliefs, values, and ideals, the study suggests a viewing of the linocut painting “Days near TếtFootnote 1” in Fig. 5 by the Vietnamese artist Bui Quang Khiem, in which some old women, perhaps very old, are selling joss papers and other cultural items nearby a tree root.

The painting wraps up our inquiry into the behavior of Vietnamese people both in folktales and in real life. Not only do fictional characters of folklore act on a number of belief and ethics systems but the Vietnamese in general are also found to add numerous things and meanings to their livelihood, places, and beliefs. The old women were not merely present but have become part of the root itself. Perhaps now the root has its soul and is worshipped by many people who live nearby. This practice echoes the long folk belief of “Thần cây đa, ma cây gạo” (literally, the banyan trees have God, Bombax ceiba have Ghost inside).

Data availability

All the data, including the original dataset, R and Stan codes for Bayesian categorical analysis, technical figures and computational results, are presented openly at Open Science Framework [http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8F7RM; ARK: c7605/osf.io/8f7rm] and Harvard Dataverse’s [https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QKGBSE].

A code sample is available in Supplementary Methods. Another example of R commands to run Stan codes was deposited in the R file “est_stan_180226_v5.R”. The computer codes in this file employed a combination of utility programmes called from the R file: “DBDA2E-utilities.R”, programs use with the book Doing Bayesian Data Analysis, Second Edition (Kruschke, 2015). The results of estimations using the above codes were also tested with the “Rethinking Package” v1.59 of Richard McElreath (https://github.com/rmcelreath/rethinking). Other programmes to run estimations for each model in the afore-mentioned series were packaged in the R file: “20180226b_rethinking_map.R”. All code used to analyze and generate the results are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

Tết is a traditional Vietnamese new year, also known as the Lunar New Year

References

Abello J, Broadwell P, Tangherlini TR (2012) Computational folkloristics. Commun ACM 55:60–70

Ackermann A (2011) Cultural hybridity: between metaphor and empiricism. In: Stockhammer, PW (ed) Conceptualizing cultural hybridization: a transdisciplinary approach. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 5-25.

Avieli N (2013) What is ‘local food?’Dynamic culinary heritage in the World Heritage Site of Hoi An, Vietnam. J Herit Tour 8(2-3):120–132

Becker A, Green E (1987) Storytelling: Art and technique, 2nd edn. R. R. Bowker, New York, NY

Blagov SA (2001) Caodaism: Vietnamese traditionalism and its leap into modernity. Nova Publishers

Bortolini E, Pagani L, Crema ER, Sarno S, Barbieri C, Boattini A, Sazzini M, Da Silva SG, Martini G, Metspalu M (2017a) Inferring patterns of folktale diffusion using genomic data. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(34):9140–9145

Bortolini E, Pagani L, Crema ER, Sarno S, Barbieri C, Boattini A, Sazzini M, da Silva SG, Martini G, Metspalu M (2017b) Reply to d’Huy et al.: Navigating biases and charting new ground in the cultural diffusion of folktales. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(41):E8556–E8556

Bronner SJ (2005) “ Gombo” folkloristics: Lafcadio Hearn’s creolization and hybridization in the formative period of folklore studies. J Folk Res 42(2):141–184

Brook T (1993) Rethinking syncretism: The unity of the three teachings and their joint worship in late-imperial China. J Chin Relig 21(1):13–44

Bunce JA, McElreath R (2018) Sustainability of minority culture when inter-ethnic interaction is profitable. Nat Human Behav 2(3):205

Choi WH, Kim DK (2013) ‘A research on the transmission and variation of tales to build korean yadam computer aided digital archive’. Appl Mech Mater: Trans Tech Publ, 307: 502–505.

Cleary JC (1991) Buddhism and popular religion in medieval Vietnam. J Am Acad Relig 59(1):93–118

Cohen R, Toninato P (2010) The creolizationdebate: analysing mixed identities and cultures. In: Robin C, Toninato P The creolization reader:Studies in Mixed Identities and Cultures. 1st. Routledge: New York, pp 1–23

Cox MR (1893) Cinderella: Three hundred and forty-five variants of Cinderella, Catskin, and Cap o’Rushes. London: Folk-lore Society.

d’Huy J, Le Quellec J-L, Berezkin Y, Lajoye P, Uther H-J (2017) Studying folktale diffusion needs unbiased dataset Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(41):E8555–E8555

D’Oca G, Hrynaszkiewicz I (2015) Palgrave Communications’ commitment to promoting transparency and reproducibility in research. Palgrave Commun 1:15013

Da Silva SG, Tehrani JJ (2016) Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales. R Soc Open Sci 3(1):150645

Do Ba K, Do Ba K, Lam QD, Le DTBA, Nguyen PL, Nguyen PQ, Pham QL (2017) Student plagiarism in higher education in Vietnam: An empirical study. High Educ Res & Dev 36(5):934–946

Dogra S (2018) Folklore and computers: The oral and the digital in computational folkloristics. Int J Humanities Soc Sci 6(1):22–27

Drell JH (1999) Cultural syncretism and ethnic identity. J Mediev Hist 25(3):187–202

Durkheim E (1897) Le suicide. Presses Électroniques de France, Paris, France

Eriksen T H (2007) Creolization in Anthropological Theory and in Mauritius. In: Stewart CCreolization:History, Ethnography, Theory. Routledge, New York, pp 153–177

Gilberto F (1946) The Master and the Slaves: A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gethin R (1998) The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Gomes A (2007) Cultural syncretism, civility, and religious diversity in Goa, India. Suomen Antropologi: J Finnish Anthro Soc 32(3): 12-24.

Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J, Iyer R, Koleva S, Ditto PH (2011) Mapping the moral domain. J Pers Soc Psychol 101(2):366

Grayson JH (1984) Religious syncretism in the Shilla period: The relationship between Esoteric Buddhism and Korean primeval religion. Asian Folkl Stud 43(2):185–198

Grayson JH (1992) The accommodation of Korean folk religion to the religious forms of buddhism: An example of reverse syncretism. Asian Folkl Stud 51(2):199–217

Hitchcox L (1990) Movement and change. In: Hitchcox L (ed) Vietnamese Refugees in Southeast Asian Camps.. Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK, pp. 21–35

Hoang VT (2017) New religions and state’s response to religious diversification in contemporary Vietnam: Tensions from the reinvention of the sacred. Springer, Switzerland

Hofstede G, Bond MH (1984) Hofstede’s culture dimensions: An independent validation using Rokeach’s value survey. J Cross Cult Psychol 15(4):417–433

Hoskins J (2012) God’s chosen people: Race, religion and anti-colonial struggle in French Indochina. ARI Working paper no. 189. Singapore: Asia Research Institute

Hoskins J (2015) The divine eye and the diaspora: Vietnamese syncretism becomes transpacific Caodaism. University of Hawai’i Press

Hoskins JA, Ninh T-HT (2017) Globalizing vietnamese religions. J Vietnam Stud 12(2):1–19

Kapchan DA (1993) Hybridization and the marketplace: Emerging paradigms in folkloristics. West Folk 52(2/4):303–326

Kendall L (2008) Editor’s introduction: Popular religion and the sacred life of material goods in contemporary Vietnam. Asian Ethnol 67(2):177

Kendall L (2011) Gods, gifts, markets, and superstition: spirited consumption from Korea to Vietnam. In: Endres K.W., Lauser A Engaging the Sprit World: Popular Beliefs and Practices in Modern Southeast Asia. Berghahn Books, New York, pp 103–120

Kendall L, Tam VTT, Huong NTT (2008) Three goddesses in and out of their shrine. Asian Ethnol 67(2):219

Klug DP (1973) The significance of the Judeo-Christian-Black concept of man and history in values education. Doctorate, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH [Online] Available at: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1486744760982123 (Accessed 27 Feb 2018).

Kruschke JK (2015) Doing Bayesian data analysis: A tutorial withR, JAGS, and Stan, 2ndeds.. Elsevier, London, UK

Kwon H (2007) The dollarization of Vietnamese ghost money. J R Anthropol Inst 13(1):73–90

Le T (2016) The common root of Three Religions (三敎同源) in the history of Vietnamese thoughts. Stud Confucianism: J Confucianism Res Inst 36(8):535–561

Le TT (2017) Thánh Tông di thảo [The remaining drafts of Thanh Tong]. Translated by: Ngo, N.B. Hanoi: Hong Duc

Lenz Dunker CI (2008) Psychology and psychoanalysis in Brazil: From cultural syncretism to the collapse of liberal individualism. Theory Psychol 18(2):223–236

Louass I (2015) La collaboration franco-caodaïste au début de la guerre d’Indochine (1945-1948) : un « pacte avec le Diable » ? » (Collaboration between French and Caodaists at the Beginning of the Indochina War (1945-1948): A “Deal with the Devil”?). Bull De l’Institut Pierre Renouvin 1(41):75–87

Ly TX (1329) Việt Điện U Linh Tập [Spiritual powers in theViet realm]. Translated by: Le, H.M. Unknown: Unknown.

Magliocco S (2010) Witching culture: Folklore and neo-paganism in America. University of Pennsylvania Press

McElreath R (2016) Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan.. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

Moretti F (2000) Conjectures on world literature. New Left Rev 54–68

Munafò MR, Nosek BA, Bishop DV, Button KS, Chambers CD, du Sert NP, Simonsohn U, Wagenmakers E-J, Ware JJ, Ioannidis JP (2017) A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat Human Behav 1(1):0021

Nguyen D-P (2017) Text as social and cultural data: a computational perspective on variation in text. Universiteit Twente, Enschede

Nguyen D (2016) Truyền kỳ mạn lục [Giant anthology of strange tales]. Hanoi: Nha Xuat Ban Hoi Nha Van.

Nguyen D, Trieschnigg D, Theune M (2013) Folktale classification using learning to rank. European Conference on Information Retrieval pp. 195–206

Nguyen DC (2014a) Kho tàng truyện cổ tích Việt Nam (quyển 1) [Collection of Vietnamese folktales, vol. 1]. Nha Xuat Ban Tre, Ho Chi Minh City, (2 vols)

Nguyen DC (2014b) Kho tàng truyện cổ tích Việt Nam (quyển 2) [Collection of Vietnamese folktales, vol. 2]. Nha Xuat Ban Tre, Ho Chi Minh City, (2 vols)

Nguyen L (2014c) Viet Nam Phat Giao Su Luan (On the history of Buddhism in Vietnam). Nha Xuat Ban Van Hoc, Hanoi

Nguyen L (2014d) Viet Nam Phat Giao Su Luan [On the history of Buddhism in Vietnam]. NXB Van hoc, Hanoi, Vietnam

Nguyen MD (1985) Culture shock - A review of Vietnamese culture and its concepts of health and disease. Cross-Cult Med 142(3):409–412

Nguyen NH (1998) The Confucian incursion into Vietnam. In: Slote, WH & Vos, GAD (eds) Confucianism and the Family: A Study of Indo-Tibetan Scholasticism. State of New York University Press: New York, pp. 91–104.

Nguyen TA (1993) Buddhism and Vietnamese society throughout history. South East Asia Res 1(1):98–114

Nguyen TD (2013) Tam giáo đồng nguyên và tính đa nguyên trong truyền thống vănTransdisciplinary Approach hóa Việt Nam [Three Religions and pluralism in Vietnamese traditional culture]. Khoa học Xã hội Việt Nam 66:35–43

Nguyen TD (2015) Some features of the ‘Vietnamization’ of Confucianism in the history of Vietnam. Stud Confucianism: J Confucianism Res Inst 33(11):497–530

Nguyen TT (2008) History of Buddhism in Vietnam. Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change. Series Iii, Asia (Book 5). Council for Research in Values & Philosophy, Washington D.C

Như-Quỳnh CT, Schafer JC (198Tibetan ScholasticismTibetan Scholasticism8) From verse narrative to novel: The development of prose fiction in Vietnam J Asian Stud 47(4):756–777

Nikolić D, Bakarić N (2016) WhTibetan Scholasticismat makes our tongues twist?: computational Analysis of croatian tongue-twisters. J Am Folk 129(511):43–54

Novak P (1987) Tao how? Asian religions and the problem of environmental degradation. ReVision 9(2):33–40

Olomola I (1988) Contradictions in Yoruba folk beliefs concerning post-life existence: The ado example. J Des Afr 58(1):107–118

On T (2016) Nguyễn Đổng Chi (1915-1984) Folktales and Fairy Tales. TraTransdisciplinary Approachditions and Texts from around the World 705–706

Park RE (1928) Human migration and the marginal man. Arno Pres: New york, 33(6) pp. 881–893.

Pedersen DB (2016) Integrating social sciences and humanities in interdisciplinary research. Palgrave Commun 2:16036

Pham DN (2005) Confucianism and the conception of the law in Vietnam. In: Gillespie J, Nicholson P (eds) Asian socialism and legal change: The dynamics of Vietnamese and Chinese reform. Asia Pacific Press at the ANU, Canberra, Australia, pp. 76–90

Pham LH, Fry GW (2004) Education and economic, political, and social change in Vietnam. Educ Res Policy Pract 3(3):199–222

Phap TT (2017) Lĩnh Nam chích quái [Selected tales of extraordinary beings in Linh Nam]. Kim Dong, Hanoi

Propp V (2010) Morphology of the Folktale. University of Texas Press

Quinn-Judge S (2013) Giving peace a chance: National reconciliation and a neutral South Vietnam, 1954-1964. Peace Change 38(4):385–410

Quintana DS, Williams DR (2018) Bayesian alternatives for common null-hypothesis significance tests in psychiatry: a non-technical guide using JASP. BMC Psychiatry 18(1):178

Raffin A (2008) Postcolonial Vietnam: hybrid modernity. Post Stud 11(3):329–344

Ringgren H (1969) The problems of syncretism. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 3: 7-14.

Seth S (2013) “Once was blind but now can see”: Modernity and the social sciences. Int Political Sociol 7(2):136–151

Slingerland EG (2003) EStockhammeffortless action: Wu-wei as conceptual metaphor and spiritual ideal in early China.. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Smith H, Novak P (2004) Buddhism: A concise introduction.. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY

Smith R (1970) An introduction to Caodaism I. Origins and early history. Bull Sch Orient Afr Stud 33(2):335–349

Stewart C (2011) Creolization, hybridity, syncretism, mixture. Port Stud 27(1):48–55

Stockhammer P W (2011) Questioning Hybridity. In: Stockhammer P.W. (Ed.) Conceptualizing CulturalHybridization: A Transdisciplinary Approach. 1st. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, Heidelberg, pp 1–13

Tangherlini TR (1994) Cinderella in Korea: Korean Oikotypes of AaTh 510. Fabula 35:282–304

Tangherlini TR (2013) The folklore macroscope. West Folk 72(1):7–27

Taylor KW (2018) What lies behind the earliest story of buddhism in ancient Vietnam? J Asian Stud 77(1):107–122

Taylor RL, Choy HYF (2005) The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Confucianism. vol. 1, The Rosen Publishing Group, New York, NY

Tehrani JJ, d’Huy J (2017) Phylogenetics meets folklore: Bioinformatics approaches to the study of international folktales. In: Kenna R, MacCarron M, MacCarron P (eds) Maths meets myths: Quantitative approaches to ancient narratives. Understanding complex systems. Springer, Cham, pp. 91–114

Thompson S (1977) The folktale. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles

Toan-Anh (2005) Nep cu: Tin nguong in Vietnam (Quyen thuong) [Old habits: Religious beliefs in Vietnam (Vol. I)]. Nha Xuat Ban Tre, Hanoi

Tran AQ (2017) Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors: An Interreligious Encounter in Eighteenth-century Vietnam. Oxford University Press

Valk Ü (2012) Legends as narratives of alternative beliefs. Belief Narrative Genres: 23–29

Vuong Q-H (2017a) Survey data on Vietnamese propensity to attend periodic general health examinations. Sci Data 4:170142

Vuong Q-H, Ho M-T, Nguyen H-K, Vuong T-T, Tran K, Ho M (2018a) “Paintings can be forged, but not feeling”: Vietnamese art—market, fraud, and value. Arts 7(4):62

Vuong Q-H, Ho T-M, Nguyen H-K, Vuong T-T (2018b) Healthcare consumers’ sensitivity to costs: A reflection on behavioural economics from an emerging market. Palgrave Commun 4(1):70

Vuong QH (2017b) ‘Open data, open review and open dialogue in making social sciences plausible’, Scientific Data Updates. Available at: http://blogs.nature.com/scientificdata/2017/12/12/authors-corner-open-data-open-review-and-open-dialogue-in-making-social-sciences-plausible/2018].

Vuong QH (2018) “How did researchers get it so wrong?” The acute problem of plagiarism in Vietnamese social sciences and humanities. Eur Sci Ed 44(3):56–58

Vuong QH, Ho T, La V-P, Nhue D, Bui Q-K, Cuong NPK, Vuong T-T, Ho M-T, Nguyen H, Pham H-H and Napier NK (2018c) ‘Cultural Additivity’and How the Values and Norms of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism Co-Exist, Interact, and Influence Vietnamese Society: A Bayesian Analysis of Long-Standing Folktales, Using R and Stan. Université Libre de Bruxelles CEB Working Paper No. 18/015

Vuong QH, La VP, Vuong TT, Ho MT, Nguyen THK, Nguyen TVH, Pham HH, Ho MT (2018d) An open database of productivity in Vietnamese social sciences and humanities for public use. Sci Data 5:180188

Vuong QH, Napier NK (2015) Acculturation and global mindsponge: an emTransdisciplinary Approacherging market perspective. Int J Intercult Relat 49:354–367

Vuong QH, Tran TD (2009) The cultural dimensions of the VietnTransdisciplinary Approachamese private entrepreneurship. IUP J Entrep Dev, VI 3&4:54–78

Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB and Bourne PE (2016) The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific data 3

Xu Y-z (2002) A thesis on the spreading and influence of taoism in vietnam. J Hist Sci 7:015

Xuan H (2018) ‘Vietnamese religious group pours water on paper burning ritual’, VnExpress, Available: VnExpress. Available at: https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnamese-religious-group-pours-water-on-paper-burning-ritual-3714647.html (Accessed 3 Mar 2018).

Young R (1995) Colonial desire: Hybridity in theory, culture, and race. London: Routledge.

Youngblood M, Lahti D (2018) A bibliometric analysis of the interdisciplinary field of cultural evolution. Palgrave Commun 4(1):120

Ziff BH, Rao PV (1997) Borrowed power: Essays on cultural appropriation. Rutgers University Press

Acknowledgements

The authors thank research staff at Vuong & Associates for assistance in collecting and preparing dataset, particularly Dam Thu Ha and Nghiem Phu Kien Cuong. This research is partially funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under the National Research Grant No. 502.01-2018.19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Quan-Hoang Vuong and Quang-Khiem Bui conceptualized the study. Quan-Hoang Vuong designed the study. Quan-Hoang Vuong and Quang-Khiem Bui trained team members for data collection and input. Manh-Toan Ho, Viet-Ha T. Nguyen, Hong-Kong T. Nguyen, Thu-Trang Vuong, Manh-Tung Ho performed the data collection and data input. Quan-Hoang Vuong and Viet-Phuong La performed the Bayesian data analysis. Quan-Hoang Vuong and Manh-Tung Ho interpreted the results. Hong-Kong T. Nguyen, Thu-Trang Vuong, Manh-Tung Ho wrote and revised the manuscript. Manh-Toan Ho created the study design’s visualization and Thu-Trang Vuong created the computational model’s visualization. Quan-Hoang Vuong supervised and administered the study. All authors read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vuong, QH., Bui, QK., La, VP. et al. Cultural additivity: behavioural insights from the interaction of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism in folktales. Palgrave Commun 4, 143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0189-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0189-2

This article is cited by

-

Emotional AI and the future of wellbeing in the post-pandemic workplace

AI & SOCIETY (2023)

-