Abstract

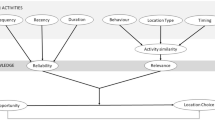

This paper presents a model of how concern about personal security (a shorthand term designed to include assessments of both fear of crime and perception of risk) influences potential victims' decisions to change location. The model examines the decision-making process from the perspective of the potential victim and provides a framework for understanding how the large amount of research on fear of crime and related topics fits together. Movement decisions are particularly appropriate given the opportunities for crime provided by the presence of possible victims in locations in which potential offenders are present. The model is designed to be used by policy makers – particularly problem-solvers, planners and security professionals who may be approaching issues related to fear of crime for the first time. Researchers may also be interested in the model's focus on looking at the situational cues of locations and the responses that potential victims may use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The specific impetus for developing this model came from the paper by Rosemary Barbaret and Bonnie Fisher (2009) on the relationship between high fear of crime and awareness of particular types of situational crime prevention measures in a sample of students from universities in one part of the United Kingdom.

The term ‘potential victim’ is used at the beginning of the paper to help focus the discussion. It is meant to include anyone who might be a victim, in other words all people in the situation, including potential offenders, as well as others who may be present and carrying out other roles, such as place managers or guardians. Later, terms such as ‘person,’ ‘actor’ and ‘people’ will be used as well to stress that potential offenders and potential victims are not distinct groups.

‘Problem-solvers’ is used here to refer to those who seek to limit crime using a problem-oriented policing approach and focusing primarily on situational crime prevention techniques (see use in Scott et al, 2008).

Other terms were considered for use here, such as ‘crime tension’ employed by Eck and colleagues in their crime-simulation models (Eck, 2009, personal communication). CPS was chosen because ‘concern’ connotes an emotional reaction that involves a cognitive element. ‘Tension’ has a more neutral connotation in terms of both emotion and cognition. On the other hand, ‘fear’ was not used because it has a much stronger connotation of emotion and implies limited cognitive involvement. This description of fear is not meant, however, to imply that it is irrational.

Concern about personal safety involves these features as well, but the focus of the assessments is different.

Sidebottom and Tilley (2008) looked at fear of crime from an evolutionary perspective and argued that it can be seen as an adaptive response to uncertain conditions. They also argued that gender differences in the level of fear displayed can be seen as evolutionarily adaptive responses, but this assertion is beyond the scope of the present discussion.

Entering a setting is not included as a movement option because the potential victim is already in a setting or location. The decision involves movement. While just two movement options could have been used, the addition of a third choice highlights the complexity of the decision-making process, even in terms of this ‘simple’ outcome.

This last group of concepts is included here for completeness and does not, at this stage of the development of the model, have any implications for the analysis of the decision-making process.

Research carried out with taxi drivers in Cardiff, Wales, however, has shown that they do use elaborated scripts when describing the potential crimes they look out for and the routine precautions they use (Smith, 2004b).

Again, this category of ‘other’ is included for completeness. It may include props and crime facilitators important for a particular crime script (see Cornish, 1994).

Concepts derived from opportunity theory may be useful for teasing out what potential victims see as related to target suitability. For example, some may use: effort, risk, reward, provocation or excuses (see Cornish and Clarke, 2003). Others may use concepts set out in acronyms, such as CRAVED - Concealable, Removable, Available, Valuable, Enjoyable and Disposable – (Clarke, 1999), which was developed to help explain the ‘choice-structuring properties’ (Cornish and Clarke, 1987) of items worth stealing. This last may be particularly helpful when the potential crime event may be some type of theft.

In this model, social disorder is considered a type of crime in progress and may be seen in terms of its linkage to other crimes, or as part of an escalating crime script, and, as such, falls within the discussion of motivated offenders.

Stanko (1990) has also discussed the role of routine precautions in preventing what she terms ‘normal violence.’

In that table, techniques are classified using the 25-techniques table set out in Cornish and Clarke (2003). The original table is available from the author.

It may be that evaluators of SCP measures may be more likely to identify CPS as a potentially affected outcome of a SCP initiative now that they have a model that uses the language of opportunity theory.

References

Barbaret, R. and Fisher, B.S. (2009) Can security beget insecurity? Security and crime prevention awareness and fear of burglary among university students in the East Midlands. Security Journal 22 (1): 3–23.

Benjamin, J.M., Hartgen, D.T., Owens, T.W. and Hardiman, M.L. (1994) Perception and incidence of crime on public transit in small systems in the Southeast. Transportation Research Record 1433: 195–200.

Brantingham, P.L. and Brantingham, P.J. (1993) Nodes, paths, and edges: Considerations of the complexity of crime and the physical environment. Journal of Experimental Psychology 13: 3–28.

Brantingham, P.J. and Brantingham, P.L. (eds.) (1981) Environmental Criminology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Brantingham, P. and Brantingham, P. (2008) Crime pattern theory. In: R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis. Collumpton, Devon, UK: Willan, pp. 78–93.

Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. (ND) Situational crime prevention evaluation database, http://www.popcenter.org/library/scp/, accessed 9 February 2009.

Clarke, R.V. (1999) Hot products: Understanding, Anticipating and Reducing Demand for Stolen Goods. London, UK: Home Office. Police Research Series, Paper No. 112.

Clarke, R.V. and Cornish, D.B. (1985) Modeling offenders' decisions: A framework for research and policy. In: M. Tonry and N. Morris (eds.) Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, Vol. 6. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 147–185.

Cobbina, J.E., Miller, J. and Brunson, R.K. (2008) Gender, neighborhood danger, and risk-avoidance strategies among urban African-American youths. Criminology 46 (3): 673–709.

Cohen, L.E. and Felson, M. (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review 44: 588–608.

Cornish, D.B. (1994) The procedural analysis of offending and its relevance for situational crime prevention. In: R.V. Clarke (ed.) Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 3. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press, pp. 151–198.

Cornish, D.B. and Clarke, R.V. (1987) Understanding crime displacement: An application of rational choice theory. Criminology 25 (4): 933–948.

Cornish, D.B. and Clarke, R.V. (2003) Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: A reply to Wortley's critique of situational crime prevention. In: M.J. Smith and D.B. Cornish (eds.) Theory for Practice in situational Crime Prevention, Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 16. Monsey, NY and Devon, UK: Criminal Justice Press and Willan Publishing, pp. 41–96.

Cornish, D.B. and Clarke, R.V. (2008) The rational choice perspective. In: R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis. Collumpton, Devon, UK: Willan, pp. 21–47.

Cornish, D.B. and Smith, M.J. (2006) Concluding remarks. In: M.J. Smith and D.B. Cornish (eds.) Secure and Tranquil Travel: Preventing Crime and Disorder on Public Travel. London, UK: University of College London, Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science, pp. 191–201.

Cozens, P., Neale, R., Hillier, D. and Whittaker, J. (2004) Tackling crime and fear of crime while waiting at Britain's railway stations. Journal of Public Transportation 7 (3): 23–41.

Eck, J.E. and Weisburd, D. (1995) Crime place and crime theory. In: J.E. Eck and D. Weisburd (eds.) Crime and Place. Crime Prevention Studies, Vol. 5. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press, pp. 1–33.

Felson, M. (1986) Linking criminal choice, routine activities, informal control, and criminal outcomes. In: D.B. Cornish and R.V. Clarke (eds.) The Reasoning Criminal: Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, pp. 119–128.

Felson, M. (2008) Routine activity approach. In: R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis. Collumpton, Devon, UK: Willan, pp. 70–77.

Felson, M. and Clarke, R.V. (1995) Routine precautions, criminology, and crime prevention. In: H.D. Barlow (ed.) Crime and Public Policy: Putting Theory to Work. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 179–190.

Ferraro, K.F. (1995) Fear of Crime: Interpreting Victimization Risk. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Fisher, B.S. and Nasar, J.L. (1992) Fear of crime in relation to three exterior site features: Prospect, refuge, and escape. Environment and Behavior 24 (1): 35–65.

Fisher, B.S. and Sloan, J.J., III (2003) Unraveling the fear of victimiztion among college women: Is the ‘shadow of sexual assault’ hypothesis supported? Justice Quarterly 20 (3): 633–659.

Fisher, B.S., Sloan III, J.J. and Wilkins, D.L. (1995) Fear of crime and perceived risk of victimization in an urban university setting. In: B.S. Fisher and J.J. Sloan, III (eds.) Campus Crime: Legal, Social, and Policy Perspectives. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, pp. 179–209.

Hirschfield, A., Bowers, K.J. and Johnson, S.D. (2004) Interrelationships between perceptions of safety, anti-social behaviour and security measures in disadvantaged areas. Security Journal 17 (1): 9–19.

Lab, S.P. (2007) Crime Prevention: Approaches, Policies and Evaluations, 6th edn., Albany, NY: Lexis-Nexis/Anderson Publishing.

LaGrange, R.L. and Ferraro, K.F. (1989) Assessing age and gender differences in perceived risk and fear of crime. Criminology 27 (4): 697–719.

Levine, N. and Wachs, M. (1985) Factors affectiong the Incidence of Bus Crime in Los Angeles, Vol. 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation Office of Technical Assistance, Urban Mass Transportation Administration.

Maxfield, M. (1984) Fear of Crime in England and Wales. London, UK: HMSO. Home Office Research Study No. 78.

Maxson, P., Browne, C., Conway, R., Mather, A. and Ridgway, J. (2001) Secure Transport Route – Manchester (Victoria) to Clitheroe Pilot. London, UK: DETR. Report by Crime Concern for the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR).

Nasar, J.L. and Fisher, B. (1993) ‘Hot spots’ of fear of crime: A multi-method investigation. Journal of Environmental Psychology 13: 187–206.

Reynald, D.M. (2008) Guardians on guardianship: Factors affecting the willingness to supervise, the ability to detect potential offenders and the willingness to intervene. Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology Annual Meeting; 12 November, St. Louis, MO.

Scott, M., Eck, J., Knutsson, J. and Goldstein, H. (2008) Problem-oriented policing and environmental criminology. In: R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis. Collumpton, Devon, UK: Willan, pp. 221–246.

Sidebottom, A. and Tilley, N. (2008) Evolutionary psychology and fear of crime. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2 (2): 167–174.

Smith, M.J. (2004a) Routine precautions used by taxi drivers: A situational crime prevention approach. Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology Annual Meeting; 17 November, Nashville, TN (available from the author).

Smith, M.J. (2004b) Developing crime prevention techniques for taxi drivers: A study of taxi drivers and crime prevention in Cardiff. Final Report for Safer Cardiff Ltd. (mimeo) (available from the author).

Smith, M.J. and Cornish, D.B. (eds.) (2006) Secure and Tranquil Travel: Preventing Crime and Disorder on Public Travel. London, UK: University of College London, Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science.

Stanko, Elizabeth (1990) Everyday Violence: How Women and Men Experience Sexual and Physical Danger. London: Pandora.

Tilley, N. (2005) Crime prevention and system design. In: N. Tilley, (ed.) Handbook of Crime Prevention and Community Safety. Collumpton, Devon, UK: Willan, pp. 266–293.

Van Andel, H. (1989) Crime prevention that works: The case of public transport in the Netherlands. British Journal of Criminology 29: 47–56.

Walklate, S. and Mythen, G. (2008) How scared are we? The British Journal of Criminology 48 (2): 209–225.

Warr, M. (1990) Dangerous situations: Social context and fear of victimization. Social Forces 68 (3): 891–907.

Warr, M. and Ellison, C.G. (2000) Rethinking social reactions to crime: Personal and altruistic fear in family households. The American Journal of Sociology 106 (3): 551–578.

Wilson, J.Q. and Kelling, G.L. (1982) Broken windows: Police and neighborhood safety. Atlantic Monthly, (March): 29–38.

Wright, R. T. and Decker, S. H. (1997) Creating the illusion of impending death: Armed robbers in action. Crimes of Violence 2, http://www.hfg.org/hfg_review/2/wright-decker.htm, accessed 10 August 2008.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Rosemary Barbaret and Bonnie Fisher for sparking my interest in fear-of-crime paradoxes. I would also like to thank Sharon Fecher for her assistance and John Eck for providing many useful insights.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, M. A six-step model of potential victims' decisions to change location. Secur J 22, 230–249 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2009.6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2009.6