Abstract

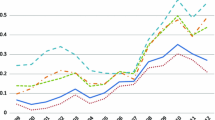

We analyze whether financial integration leads to converging or diverging business cycles using a dynamic spatial model. Our model allows for contemporaneous spillovers of shocks to GDP growth between countries that are financially integrated and delivers a scalar measure of the spillover intensity at each point in time. For a financial network of ten European countries from 1996 to 2017, we find that the spillover effects are positive on average and much larger during periods of financial stress, pointing towards stronger business cycle synchronization. Dismantling GDP growth into value added growth of ten major industries, we observe that spillover intensities vary significantly. The findings are robust to a variety of alternative model specifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Acemoglu et al. (2012), for example, emphasizes the relevance of the network structure for spillover effects between sectors.

International co-movement through firms in one country and their cross-border links is analyzed by, for example, Di Giovanni et al. (2018) and Kleinert et al. (2015). The role of trade among countries for business cycle synchronization is assessed by Abbott et al. (2008) or Arkolakis and Ramanarayanan (2009). In our model specification, we control for trade linkages, which might be a relevant driver of business cycle synchronization, while our main focus is on the role of financial linkages.

While financial integration can take different forms, Hoffmann et al. (2019) find that banking integration dominates equity market integration in the euro area with the latter being still limited in size.

While inter-office positions might change faster between inter-related offices compared to other cross-border positions, the series is still sufficiently stable such that no concerns due to volatility emerge.

Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, UK. In terms of financial assets (in Euros, unconsolidated) of the economy obtained from Eurostat, our countries cover on average over the sample period, more than 78% of the European countries’ financial assets (EU28 and Switzerland).

The continuous reporting of cross-border positions is needed to construct the weight matrix as explained in the next section. In robustness tests, we add non-European countries when analyzing GDP growth.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing. Arts, entertainment, recreation, and other services. Construction. Financial and insurance activities. Industry (except construction). Information and communication. Professional, scientific, and tech activities. Public administration, deference, education, human health and social work. Real estate activities. Wholesale and retail trade, transport, accommodation, and food.

For example, the EU Klems Database or the OECD provides information on value added by industry as well but only at a yearly frequency. Similarly, the United Nations Statistical Yearbook would only offer data on a yearly frequency and with a less detailed breakdown by industry.

Economic theory suggests that economic growth is determined by production factors such as technology, labor input, as well as capital and government expenditure (Barro and Lee 1994; Moral-Benito 2012; Jorgenson 1988; Sala-i-Martin et al. 2004; Solow 1962; Zeira 1998). More recent studies focus on the role of financial or trade integration for economic development (Guiso et al. 2004; Kose et al. 2006; Schularick and Steger 2010). We test for the robustness of results when excluding controls in Sect. 4.

In Sect. 4, we test the sensitivity of our main result to issues related to reverse causality, which might arise when relating GDP growth to controls such as labor productivity or gross fixed capital formation.

To ensure weak exogeneity, the trade data matrices are lagged by four quarters. Furthermore, each matrix is normalized by its largest eigenvalue.

In our estimations, the dependent variable observations are transformed to have mean zero and unit standard deviation, to account for country heterogeneity, which justifies the absence of fixed effects and heterogeneous variances.

For convenience, we refer to the weight matrix including the lagged financial linkages as \(W_{t}\) throughout the paper.

See www.gasmodel.com for a more complete compilation of papers.

It is to note that the reduced form of the spatial lag model with spatial errors is nonlinear and can not be estimated using least squares, because it is not possible to linearly disentangle \(\rho _t\), \(\beta\), and \(\delta\). However, building on arguments from White (1996) it has been shown in Blasques et al. (2016) that under some regularity conditions the maximum likelihood estimator of the static coefficients in the score-driven spatial model, including \(\omega , A, B, \beta , \delta , \sigma ^2,\) and \(\nu\), (the first three of which, together with the data, provide the ingredients for \(\rho _t\)) is uniquely identified, consistent, and asymptotically normally distributed.

The results are robust towards employing an alternative model specification using OLS regressions with covariates, no spatial term, country and year fixed effects. These results are available upon request.

For simplicity, we abstract from the regressors and the spatial error dependence.

Please note that this analysis is a sector-by-sector analysis without considering cross-sectoral spillovers.

The full tables covering all models per industrial sector can be obtained upon request.

This sector comprises mostly legal, management or engineering activities, see: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:F1_Sectoral_analysis_of_Professional,_scientific_and_technical_activities_(NACE_Section_M),_EU-28,_2016.png.

The role of shock spillovers between interconnected sectors depending on the network structure is discussed by Acemoglu et al. (2012).

The presence of multinational firms as such can result in international co-movements (Cravino and Levchenko (2017); Di Giovanni et al. (2018); Kleinert et al. (2015)). Such co-movements can be fueled in case multinational banks follow their multinational customers (Buch (2000)), in this context it is also important that we do not net out inter-office positions between banks.

E.g., for the United States, Laeven and Valencia (2013) show high values of external dependence for machinery, other industries or professional goods. Kroszner et al. (2007) find that sectors relying more on external finance via banks are hit more by banking crises and consequently tighter financial constraints (see also, Braun and Larrain (2005); Chava and Purnanandam (2011)).

Unfortunately, we can not extend our sample period backwards due to changes in the reporting standards of the BIS.

E.g., Kalemli-Ozcan et al. (2013a) find different spillover patterns from 2007 onwards, which guides the choice of sample periods to compute average in/direct effects.

References

Abbott, A., J. Easaw, and T. Xing. 2008. Trade integration and business cycle convergence: Is the relation robust across time and space? The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 110 (2): 403–417.

Acemoglu, D., V.M. Carvalho, A. Ozdaglar, and A. Tahbaz-Salehi. 2012. The network origins of aggregate fluctuations. Econometrica 80 (5): 1977–2016.

Arkolakis, C., and A. Ramanarayanan. 2009. Vertical specialization and international business cycle synchronization. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 111 (4): 655–680.

Barro, R.J., and J.-W. Lee. 1994. Sources of economic growth. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 40: 1–46.

Blasques, F., S.J. Koopman, A. Lucas, and J. Schaumburg. 2016. Spillover dynamics for systemic risk measurement using spatial financial time series models. Journal of Econometrics 195 (2): 211–223.

Braun, M., and B. Larrain. 2005. Finance and the business cycle: International, inter-industry evidence. The Journal of Finance 60 (3): 1097–1128.

Buch, C.M. 2000. Why do banks go abroad? Evidence from German data. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments 9 (1): 33–67.

Catania, L., and A.G. Billé. 2017. Dynamic spatial autoregressive models with autoregressive and heteroskedastic disturbances. Journal of Applied Econometrics 32 (6): 1178–1196.

Cerutti, E., S. Claessens, and A.K. Rose. 2019. How important is the global financial cycle? Evidence from capital flows. IMF Economic Review 67 (1): 24–60.

Cesa-Bianchi, A., J. Imbs, and J. Saleheen. 2019. Finance and synchronization. Journal of International Economics 116: 74–87.

Chava, S., and A. Purnanandam. 2011. The effect of banking crisis on bank-dependent borrowers. Journal of Financial Economics 99 (1): 116–135.

Cravino, J., and A.A. Levchenko. 2017. Multinational firms and international business cycle transmission. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (2): 921–962.

Creal, D., S.J. Koopman, and A. Lucas. 2011. A dynamic multivariate heavy-tailed model for time-varying volatilities and correlations. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 29 (4): 552–563.

Creal, D., S.J. Koopman, and A. Lucas. 2013. Generalized autoregressive score models with applications. Journal of Applied Econometrics 28: 777–795.

Davis, J.S. 2014. Financial integration and international business cycle co-movement. Journal of Monetary Economics 64: 99–111.

Denbee, E., C. Julliard, Y. Li, and K. Yuan. 2021. Network risk and key players: A structural analysis of interbank liquidity. Journal of Financial Economics 141 (3): 831–859.

Di Giovanni, J., A.A. Levchenko, and I. Mejean. 2018. The micro origins of international business-cycle comovement. American Economic Review 108 (1): 82–108.

Frankel, J.A., and A.K. Rose. 1998. The endogenity of the optimum currency area criteria. The Economic Journal 108 (449): 1009–1025.

Guiso, L., T. Jappelli, M. Padula, M. Pagano, P. Martin, and P.-O. Gourinchas. 2004. Financial market integration and economic growth in the EU. Economic Policy 19 (40): 525–577.

Harvey, A.C. 2013. Dynamic Models for Volatility and Heavy Tails. Econometric society monographs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Herskovic, B., B. Kelly, H. Lustig, and S. Van Nieuwerburgh. 2020. Firm volatility in granular networks. Journal of Political Economy 128 (11): 4097–4162.

Hoffmann, M., E. Maslov, B.E. Sørensen, and I. Stewen. 2019. Channels of risk sharing in the Eurozone: What can banking and capital market union achieve? IMF Economic Review 67 (3): 443–495.

Imbs, J. 2004. Trade, finance, specialization, and synchronization. The Review of Economics and Statistics 86 (3): 723–734.

Imbs, J. 2006. The real effects of financial integration. Journal of International Economics 68 (2): 296–324.

Inklaar, R., R. Jong-A-Pin, and J. De Haan. 2008. Trade and business cycle synchronization in oecd countries-a re-examination. European Economic Review 52 (4): 646–666.

Jorgenson, D.W. 1988. Productivity and economic growth in Japan and the United States. The American Economic Review 78 (2): 217–222.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., E. Papaioannou, and F. Perri. 2013. Global banks and crisis transmission. Journal of International Economics 89 (2): 495–510.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., E. Papaioannou, and J.-L. Peydró. 2013. Financial regulation, financial globalization, and the synchronization of economic activity. The Journal of Finance 68 (3): 1179–1228.

Kleinert, J., J. Martin, and F. Toubal. 2015. The few leading the many: Foreign affiliates and business cycle comovement. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7 (4): 134–59.

Kose, A.M., E.S. Prasad, and M.E. Terrones. 2003. How does globalization affect the synchronization of business cycles? American Economic Review 93 (2): 57–62.

Kose, M.A., C. Otrok, and E. Prasad. 2012. Global business cycles: Convergence of decoupling? International Economic Review 53 (2): 511–538.

Kose, M.A., E.S. Prasad, and M.E. Terrones. 2006. How do trade and financial integration affect the relationship between growth and volatility? Journal of International Economics 69 (1): 176–202.

Kroszner, R.S., L. Laeven, and D. Klingebiel. 2007. Banking crises, financial dependence, and growth. Journal of Financial Economics 84 (1): 187–228.

Laeven, L., and F. Valencia. 2013. The real effects of financial sector interventions during crises. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 45 (1): 147–177.

Moral-Benito, E. 2012. Determinants of economic growth: A bayesian panel data approach. The Review of Economics and Statistics 94 (2): 566–579.

Morgan, D.P., B. Rime, and P.E. Strahan. 2004. Bank integration and state business cycles. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (4): 1555–1584.

Sala-i-Martin, X., G. Doppelhofer, and R.I. Miller. 2004. Determinants of long-term growth: A bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach. The American Economic Review 94 (4): 813–835.

Schnabel, I., and Seckinger, C. 2015. Financial fragmentation and economic growth in Europe. CEPR Discussion Papers 10805, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.

Schularick, M., and T.M. Steger. 2010. Financial integration, investment, and economic growth: Evidence from two eras of financial globalization. The Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (4): 756–768.

Solow, R.M. 1962. Technical progress, capital formation, and economic growth. The American Economic Review 52 (2): 76–86.

Tonzer, L. 2015. Cross-border interbank networks, banking risk and contagion. Journal of Financial Stability 18: 19–32.

White, H. 1996. Estimation, inference and specification analysis, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zeira, J. 1998. Workers, machines, and economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113 (4): 1091–1117.

Acknowledgement

We thank two anonymous referees and Emine Boz, Michael Barkholz, Franziska Bremus, Michela Rancan, and Katheryn Russ for very helpful comments and discussions. Funding from the European Social Fund (ESF) of the European Commission is gratefully acknowledged by Lena Tonzer. Julia Schaumburg thanks the Dutch Science Foundation (NWO, grants VENI451-15-022 and VI.Vidi.191.169) for financial support. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. All errors are solely our own responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Böhm, H., Schaumburg, J. & Tonzer, L. Financial Linkages and Sectoral Business Cycle Synchronization: Evidence from Europe. IMF Econ Rev 70, 698–734 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-022-00173-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-022-00173-9