Abstract

Cultures explicitly and implicitly create and reinforce social norms and expectations, which impact upon how individuals make sense of and experience their place within that culture. Numerous studies find substantial differences across a range of behavioral and cognitive indices between what have been called “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD)” societies and non-WEIRD cultures. Indeed, lay conceptions and social norms around wellbeing tend to emphasize social outgoingness and high-arousal positive emotions, with introversion and negative emotion looked down upon or even pathologized. However, this extravert-centric conception of wellbeing does not fit many individuals who live within WEIRD societies, and studies find that this mismatch can have detrimental effects on their wellbeing. There is a need to better understand how wellbeing is created and experienced by the large number of people for whom wellbeing manifests in alternative ways. This study investigated one such manifestation—the personality trait of sensory processing sensitivity (SPS)—qualitatively investigating how sensitive individuals experience and cultivate wellbeing within a WEIRD society. Twelve adults participated in semi-structured interviews. Findings suggest that highly sensitive individuals perceive that wellbeing arises from harmony across multiple dimensions. Interviewees emphasized the value of low-intensity positive emotion, self-awareness, self-acceptance, positive social relationships balanced by times of solitude, connecting with nature, contemplative practices, emotional self-regulation, practicing self-compassion, having a sense of meaning, and hope/optimism. Barriers of wellbeing included physical health issues and challenges with saying no to others. This study provides a rich idiographic representation of SPS wellbeing, highlighting diverse pathways, which can lead to wellbeing for individuals for whom wellbeing manifests in ways that contradict the broader social narratives in which they reside.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wellbeing is shaped by a wide range of factors, including our genes, early life experiences, personality, situations encountered, the choices we make, the behaviors we engage in, the social environments in which we live, and the intricate ways in which these factors interact (Eckersley et al., 2007). Beyond the individual, each of these factors intersect with and are influenced by culture. Culture can be described as “a network of knowledge that is produced, distributed, and reproduced among a collection of interconnected people” (Chiu and Chen, 2004, p. 173). Culture creates, defines, and maintains the values, norms, attributes, and behaviors that are seen as appropriate (or not) for a collection of people (Benet-Martínez, 2006). The nature and experience of wellbeing “depends on how the concepts of ‘well’ and ‘being’ are defined and practiced” in any given society or culture (Kitayama and Markus, 2000, p. 115).

Wellbeing is a growing area of interest worldwide (Delle Fave et al., 2013; Helliwell et al., 2016; The Treasury New Zealand Government, 2019). A range of theoretical and empirical wellbeing models, frameworks, measures, and interventions have emerged, providing a general understanding of what wellbeing is and how it can be improved. Although recent years have expanded wellbeing research and practice worldwide, much of this literature has occurred in what have been called “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic” (WEIRD) countries, including the US, the UK, and Australia (Henrich et al., 2010a, 2010b). Numerous studies find significant differences between WEIRD and non-WEIRD societies across a range of behavioral and cognitive indices (e.g., Benet-Martínez, 2006; Disabato et al., 2020; Hendriks et al., 2019; Koopmann-Holm and Tsai, 2014; Laajaj et al., 2019; Lim, 2016; Tsai et al., 2006; Tsai et al., 2006; Tsai and Park, 2014; Wong et al., 2011). While most of the existing wellbeing models contend that wellbeing is nuanced and multi-dimensional, including eudaimonic and low-arousal dimensions, lay conceptions of—and social norms within—WEIRD societies tend to favor high-arousal emotions (Tsai, 2007), exemplified by extraverted, socially outgoing, high-energy individuals (Allik, 2005; Christopher and Hickinbottom, 2008; Davidson et al., 2015; Frawley, 2015; Fulmer et al., 2010; Lu and Gilmour, 2004; Uchida and Kitayama, 2009). Introversion (a personality characteristic) and negative emotions (a wellbeing characteristic) are looked down upon or even pathologized (e.g., Davidson et al., 2015; Fudjack, 2013). However, this extravert-centric conception of wellbeing does not fit many individuals who live within WEIRD societies, and this mismatch can have detrimental effects on these individuals’ wellbeing (Fulmer et al., 2010; Stephens et al., 2012). There is a need to better understand how happiness is created and experienced by the large number of people for whom wellbeing manifests in alternative ways.

Further, while influences of culture on personality (Diener et al., 2003; Triandis and Suh, 2002) and wellbeing (Diener, 2000; Disabato et al., 2016; Galinha et al., 2013; Mathews, 2012) are well recognized, studies often follow nomothetic approaches, focusing on identifying generalizable patterns and norms across numerous people. Less is known about idiographic experiences of individuals who might not fit those norms. This study investigated one such manifestation—the personality trait of sensory processing sensitivity (SPS)—qualitatively investigating how sensitive individuals experience and cultivate wellbeing within a WEIRD society.

Life within yet beyond social norms

Much of the research linking personality and wellbeing has been conducted with participants embedded within WEIRD countries (Disabato et al., 2020), where extravert-centric perceptions of wellbeing dominate (Fulmer et al., 2010). Yet the influence of these cultural norms on findings is mostly unacknowledged. Such studies often generalize findings, assuming universal notions of wellbeing (Zevnik, 2014), without recognizing the surrounding culture that values a particular type of wellbeing—one that does not apply to everyone within that culture (Christopher, 1999). One way of addressing this issue is to judiciously choose a select group of populations that can provide a test of universality (Henrich et al., 2010a); the current qualitative study does just this.

Research indicates that when people are matched with their cultural environment, they experience higher rates of psychological wellbeing (Fulmer et al., 2010) and less negative emotion (Stephens et al., 2012) than those who feel a mismatch with the surrounding culture. When more extraverted individuals are part of a more extraverted culture, they experience greater wellbeing than introverted individuals within the same context (Fulmer et al., 2010). This means that the dominance of social norms can negatively impact upon individuals who experience wellbeing in different ways.

Indeed, well before the recent upsurge of interest in wellbeing-related research and topics, Henjum (1982) suggested that “it is not very complimentary to be called an introvert in our society” (referring to American society; p. 39). Echoing this sentiment, Eysenck (1983) posited that “happiness is a thing called stable extraversion” (p. 67). This still rings true today in WEIRD societies, where there appears to be a tacit approval of extraverted behaviors, with a corresponding negative judgment for introverted behaviors (Davidson et al., 2015; Fulmer et al., 2010). Indeed, studies in Australia, where the current study was conducted, show a distinctive cultural preference for extraversion (Lawn et al., 2018).

This dominant view of extraversion as desirable and preferable is accompanied by some potentially harmful consequences—such as the pathologizing of introversion. For instance, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-9; World Health Organization, 1978) has for several decades (until the release of ICD-10) listed “introverted personality” (Code 301.21) and “introverted personality disorder of childhood” (Code 313.22) as personality disorders. Indeed, introversion has been equated with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Grimes, 2010) and with schizophrenia (McWilliams, 2006; Wells, 1964). Just a decade ago (Pierre, 2010; Steadman, 2008), proposals were advanced that introversion be listed as a personality disorder for the DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). While this did not eventuate, several personality disorders include introverted traits as part of their diagnostic criteria (e.g., Avoidant Personality Disorder, Schizoid Personality Disorder (DSM-V, 2013). Notably, even though the DSM-V cautions practitioners to consider culture-related issues when diagnosing these disorders, this advice does not extend to acknowledging the extravert-centric culture from which the DSM emerged. Such debates highlight the need to advocate for the quieter members of our WEIRD societies—those who fall on the more introverted and sensitive end of these continuums.

Essentially, this means that introverted individuals (and other sensitive members of society) existing within WEIRD cultures may experience a poor fit with their wider cultural context. Indeed, studies suggest that introverted students feel out of place in extravert-centric classrooms (Davidson et al., 2015; Henjum, 1982). The socially accepted norms around ways of behaving and ways of being well in WEIRD cultures can leave introverts feeling invalidated (Fulmer et al., 2010), or feeling pressured to fit in and less authentic (Lawn et al., 2018), with implications for opportunities for—and experiences of—wellbeing.

Links between personality and wellbeing

Interest in human wellbeing has occurred across millennia (Crisp, 2014), and while recent years have brought considerable interest and focus on wellbeing, there remains little consensus on what wellbeing is, with robust discussions occurring on how to appropriately define and measure the construct (Cooke et al., 2016; Disabato et al., 2016; Goodman et al., 2017; Kern et al., 2019). For our purposes here, we focus on subjective aspects, or how individuals perceive their life (Huppert, 2014). We define wellbeing as a flexible state of high-quality psychosocial functioning—feeling good and doing well across a range of cognitive, emotional, and social domains.

Associations between wellbeing and personality have long been recognized. For example, trait-focused studies consistently find that extraversion and neuroticism link to positive (e.g., life satisfaction, happiness, positive affect) and negative (e.g., negative affect) wellbeing outcomes, respectively (DeNeve and Cooper, 1998; McCrae and Costa, 1991; Smillie, 2013; Smillie et al., 2015). Conscientiousness demonstrates moderate correlations with affective dimensions, with stronger associations with achievement and social competence dimensions (Friedman and Kern, 2014; Steel et al., 2008). Beyond trait-focused research, narrative studies find that coherence of one’s self narrative identity links to greater wellbeing (Baerger and McAdams, 1999), generativity, and psychosocial adaptation (McAdams and Guo, 2015). Interestingly, it appears that wellbeing benefits can arise not only from personality characteristics themselves, but also from engaging in behaviors that reflect those characteristics. For instance, studies find that acting in an extraverted manner increases positive affect and happiness levels, even for introverted individuals (Fleeson et al., 2002; Smillie et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017; Zelenski et al., 2012).

Studies focused on personality and wellbeing have primarily taken a nomothetic approach, attempting to identify general associations across populations, while ignoring individual variations from the norms. Less is known about individual experiences of wellbeing, especially when those experiences run counter to social norms that define the outcomes studied.

Sensory processing sensitivity

The current study specifically focuses on experiences of wellbeing for people that are highly sensitive. Sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) is commonly characterized by a propensity for deep and complex processing of sensory information, easy over-arousal from sensory input (e.g., strong smells and tastes, sounds, temperatures), strong emotional reactivity and empathy, and increased awareness of subtleties in the environment (Aron and Aron, 1997). The trait is relatively continuously distributed, and individuals can be grouped into low, medium, and high levels of sensitivity (Lionetti et al., 2018; Pluess et al., 2018). High SPS is relatively common; recent studies estimate that ~25% of the general population can be classified as scoring high on SPS (Greven et al., 2019). Notably, although the trait appears to have some overlapping characteristics with introversion, ~30% of high-SPS individuals also score high on extraversion. Just as introversion is not highly valued in WEIRD cultures (Fulmer et al., 2010), sensitivity is not highly valued (Aron, 1996, 2004), and high-SPS individuals living in Australia might feel a mismatch between their innate attributes and the culture in which they live (Aron, 2011).

Despite its prevalence, SPS is an under-researched trait, especially in relation to wellbeing. Existing SPS/wellbeing research associates high SPS with a range of maladaptive outcomes such as anxiety (Bakker and Moulding, 2012; Meredith et al., 2016), internalizing problems (Boterberg and Warreyn, 2016), depression (Brindle et al., 2015; Yano et al., 2019), social phobia (Neal et al., 2002), and low levels of life satisfaction (Booth et al., 2015), among others. Still, a few studies focused on functional aspects of SPS do exist, suggesting that high-SPS can also relate to positive outcomes (Black and Kern, 2020. Personality and flourishing: exploring Sensory Processing Sensitivity and wellbeing in an Australian adult population (unpublished manuscript); Sobocko and Zelenski, 2015; Yano et al., 2020).

The current study

Despite apparent mismatches between SPS characteristics and WEIRD socially accepted norms around behaviors and wellbeing, some highly sensitive persons (HSPs) do achieve high levels of wellbeing (Black and Kern, 2020. Personality and flourishing: exploring Sensory Processing Sensitivity and wellbeing in an Australian adult population (unpublished manuscript)). How do they do this? As promoting high levels of wellbeing is a goal worth pursuing for any community, organization, or government amongst its citizens (Hone et al., 2014), it is important to know what wellbeing looks like for individuals within society, not just relying on trends for the majority.

Following a nomothetic perspective, in an initial quantitative study (Black and Kern, 2020. Personality and flourishing: exploring Sensory Processing Sensitivity and wellbeing in an Australian adult population (unpublished manuscript)), 430 individuals completed a wellbeing survey that examined associations between a variety of wellbeing domains and sensitivity using existing wellbeing measurement tools. The study provided trends of SPS and wellbeing across a sizable number of individuals. Participants ranged both in terms of SPS scores and reported wellbeing across a range of dimensions. To better understand the experiences and perspectives of high-SPS individuals, the current study adds an idiographic exploration of how high-SPS individuals conceive of and experience wellbeing, using qualitative interviews with a subset of high-SPS individuals. As Hefferon et al. (2017) noted, qualitative approaches can “provide in-depth access to phenomena that links experiences and processes with emotions, thoughts, and behaviors” (p. 214), which can provide richer explorations of individual experiences than can be attained through quantitatively based measures alone. The current study aimed to investigate how high-SPS individuals living within an extravert-dominant social context conceive of and experience wellbeing.

Methods

Participants

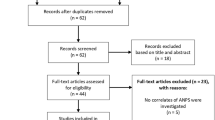

The current study used a subset of respondents from the Wellbeing and Highly Sensitive Person study (Black and Kern, 2020. Personality and flourishing: exploring Sensory Processing Sensitivity and wellbeing in an Australian adult population (unpublished manuscript)), which included 430 individuals living in Australia. In the larger study, 152 participants scored high on wellbeing; of these, ~24% (n = 37; 2 males, 34 females, 1 other gender) could be classified as high SPS. Of these 37 high-SPS/high-wellbeing respondents, 27 indicated willingness to potentially be interviewed, with interviews successfully conducted with 12 individuals (1 male, 11 females). Interviewees ranged in age from 19 to 69 and were of Asian (n = 4) or White Australian (n = 8) descent and reported good physical health. There were no significant differences in wellbeing and SPS scores between male and female, or between Asian and White Australian ethnicity interview participants. Half the participants were studying either full-time or part-time, and two thirds of participants were employed in full-time or part-time work.

Measures

As part of the larger study, participants completed the Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSPS; Aron and Aron, 1997), the PERMA-Profiler (Butler and Kern, 2016), and the self-acceptance, autonomy, and personal growth sub-scales from the Psychological Wellbeing scales (PWB; Ryff and Singer, 1996). All 37 participants in the high-SPS/high-wellbeing group had relatively high scores compared to the rest of the larger sample on these measures.

The first author conducted interviews via videoconferencing, using a semi-structured questionnaire with 13 prompts (see Supplementary Information: https://doi.org/10.26188/5ea7b3d94f5b9). Interviews ranged from 25 to 110 min in length, with an average duration of 49 min (SD = 23.17).

Ethical considerations

All procedures were approved by the University of Melbourne’s Office of Research Ethics and Integrity. Participants were invited to participate in interviews via a personal email from the interviewer, which explained that participation was voluntary, and that all data would be treated confidentially. A copy of interview questions was also included in the email invitations. Participants were able to choose a suitable interview time via a secure online scheduling application, and informed consent was obtained before starting and recording each interview. To preserve anonymity, names and identifying information have been removed from what is reported here.

Data analysis

Recorded interviews were transcribed and analyzed by the first author, using an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) process (Smith et al., 1999). NVivo 11 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Released, 2015) was used to support analyses. IPA seeks to examine personal, lived experience and get as close to the participant’s personal world as possible (Smith, 1996). First, all interviews were transcribed. Second, each transcribed interview was sent to the interviewee for validation. Third, each transcript was read several times. Fourth, parts of the text that were relevant to wellbeing were highlighted. Fifth, key words were used to capture emerging theme titles, which were later designated as dimensions (Smith et al., 1999). Some dimensions followed the questions on the interview schedule, but new ones also emerged. Sixth, connections between dimensions were identified, and were clustered together to eliminate redundancy. Finally, the dimensions were grouped into key themes (Smith et al., 1999). Because of the nature of interview data, quotes can include multiple themes.

Limitations, boundaries, and potential for bias

For transparency, we note several limitations of our approach, boundaries of generalization, and characteristics of the authors that could impact upon the analyses and interpretations of the data.

Personality research has long struggled to reconcile competing agendas between nomothetic approaches and the idiographic study of people’s unique experiences in life (McAdams and Olsen, 2010). Our study addresses the misbalanced focus on nomothetic approaches by bringing an idiographic focus for a particular population, aiming to understand the perceptions and experiences of individuals, rather than identifying trends that capture the collective, focusing on depth rather than breadth. In qualitative interpretative phenomenological research (such as this), a sample size of 6–8 participants is considered acceptable for in-depth interviews (Eatough and Smith, 2017; Smith, 2017; Smith and Eatough, 2011; Smith et al., 2009). Our study included twelve participants, and thus aligns with these recommendations. However, due to the small sample size, the findings should not be generalized to all high-SPS individuals.

Further, while it might be useful to compare high-SPS and low-SPS experiences, such comparisons undermine the value of understanding high-SPS experiences in and of themselves. There may be something distinctive about high-SPS wellbeing, and the interviews might have some important insights for low or moderate SPS individuals as well. Such comparisons are beyond our scope here. Subsequent studies might consider the extent to which the results reported here are generalizable, distinctive, and useful.

As interviews were completed at a single period in time, participant responses and our analysis of those responses are impacted by the contemporary sociohistorical context. Although our interview group was demographically diverse, future studies should include a wider mix of participants of different genders, socio-economic backgrounds, ages, cultures, and historical periods in time.

Within the semi-structured interviews (see Supplementary Information), the interviewer noted several examples of wellbeing (e.g., positive emotions, absorption). The examples were included to encourage participants to think about positive aspects of wellbeing, rather than on mental illness and the lack of dysfunction. The interviewer ensured that participants understood that they were invited to explain wellbeing from their own perspective. However, it is possible that the prompts colored participants’ responses.

In addition, the authors have backgrounds in educational counseling, teaching, psychology, and wellbeing research. We both score high on SPS; while this may have influenced the interpretation of results, it also allowed the interviewer to respond to distinct cues provided by the participants.

Results

As summarized in Table 1, 32 dimensions were identified. Analysis of participants’ interviews revealed three key themes related to wellbeing: conceptions of wellbeing, how wellbeing is enabled, and barriers of experiencing wellbeing.

Conceptions of wellbeing

The first theme that emerged reflected how interviewees conceptualized wellbeing. All participants portrayed a multi-dimensional view, mentioning emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social/relational dimensions.

Eight participants highlighted that the emotional dimension was represented by low-arousal positive emotions, such as calmness, relaxation, and peacefulness, rather than the high-arousal emotions typical of WEIRD cultures. For example, one noted that wellbeing is when they “just feel relaxed and calm and peaceful,” and another participant shared “for me, it’s less exuberant happiness, and more the kind of contented, softer, and being comfortable in my space and with myself.”

Nine participants conceptualized wellbeing as a balance or harmony across multiple dimensions. For example, one participant described wellbeing as “a wheel with different segments, and I have to look after all the different segments in order for the wheel to roll.” Another participant noted:

“trying to have a balance of everything, so like physical health, eating well, having time to do things that you enjoy…like hobbies, and things like that outside work. Basically, finding a balance between those things.”

Participants commonly expressed harmonizing among psychosocial dimensions (e.g., “negative emotion, positive emotion, feelings of connectedness between people”). Others further included a cognitive dimension, reflecting self-knowledge and self-appreciation. For instance, one participant described wellbeing as “when you feel like the best self that you know you can be,” while another participant noted “being very comfortable in my space and with myself.” Another person included a spiritual dimension: “my relationship with God, and then also a sense of meaning in life.”

Enablers of wellbeing

The second main theme that emerged reflected strategies that enable high-SPS individuals to experience wellbeing. Aligned with seeing wellbeing as multi-dimensional in nature, interviewees suggested that many of the enablers impact across multiple wellbeing dimensions. For example, mindfulness was seen as contributing to emotional, cognitive, spiritual, and relational wellbeing. While we grouped enablers into different domains (emotional, cognitive, behavioral, social), this is simply for ease of communicating the results. Arguably, many of the enablers target multiple domains (e.g., contemplative practices can be emotional, cognitive, and behavioral in nature). Strategies generally focused on regulating emotions, cognitions, behaviors, and social processes. Participants also pointed to personal characteristics that may help buffer wellbeing.

Emotion-focused enablers

Eight interviewees shared how regulating their emotions helped improve their wellbeing. For example, one participant reported benefits in being able to take time in responding to negative stress and emotion. Another interviewee spoke of re-framing her internal dialog, suggesting her emotional self-regulation abilities had improved over time: “everyone has these moments and it’s not catastrophizing like I used to, but just being a bit more comfortable sitting with it, and thinking it’ll pass and it’ll work out.” One participant described feeling a sense of empowerment through choosing “the response that’s going to give you the outcome you want”, and another shared “I love feeling empowered to choose the way that I respond.”

Cognition-focused enablers

Most participants pointed to self-awareness and self-acceptance. Ten participants spoke to the importance of purposeful cognitive recognition of the self, including awareness of their own wellbeing needs. For instance, one participant noted, “I know the pathways that work for me, and I know the dosages on different days.” Others pointed to being aware of their needs and proactively acting upon those needs: “I’ve got to integrate some rest in there, or whatever I need”; and from another “I’m a lot more aware, physically, of the sensations of stress in my body.” One person noted the importance of “reminding myself to appreciate, you know, and to look at what’s there instead of what isn’t.” Self-awareness was beneficial when coupled with self-acceptance. For instance, one participant reflected on wellbeing as accepting one’s limitations and asking for assistance when needed: “part of that wellbeing is knowing when I need help and requesting it in an effective manner.”

All 12 interviewees believed that self-compassion was a significant contributor to their wellbeing. Several participants believed that self-compassion involved being kind to themselves through self-talk, such as using “self-talk like ‘this will pass’ and ‘it’s just a stressful time’ and ‘it’ll be okay’,” and telling oneself “I’ve been trying to do that with myself, treat myself the way I’d treat somebody I love.” One interviewee spoke of “being able to forgive myself for mistakes,” while another described self-compassion as being non-judgmental to the self: “I think compassion is a positive thing, and non-judgmental is neutral, I think. I’m just neutral to myself.” For some participants, their practice of self-compassion involved “being patient with myself,” and re-framing their internal dialog, for instance one participant shared, “I’m very conscious of the language that I use, so I’ve gotten rid of the word ‘should’.” For another participant, self-compassion was “very much about listening to what my body is telling me, but also being reflective on the way I respond to situations and respond to particular people.” One interviewee noted how practicing self-compassion helped alleviate her stress levels, “if you’re hard on yourself all the time, then you can never not be stressed.” Still, several participants noted that self-compassion was a work in progress. For example, one participant shared, “it’s something I have struggled with but I think that I’m getting better at it,” and another shared, “I think a lot of us can be hard on ourselves, but that’s one area I probably need to work on.”

Behavioral enablers

All participants reported the importance of engaging in regular activities such as physical, mental, and self-care behaviors. For example, one participant noted “every day I try to do something—it’s exercise or coming home and reading a book.” Another noted: “I do craft stuff at night. I give myself that hour to just not think about anything.” Others pointed to physical activity and exercise: “eating healthy food, and doing exercises every day” and “I think yoga and walking are incredibly important for me […] if I’m busy and I don’t get to walk one day I can survive, but my days with walking and yoga are so much better.”

These behavioral activities included exercise or movement, contemplative practices, and connecting with nature. For instance, half of the participants noted that connecting with nature was an important enabler of their wellbeing. Interestingly, all six participants mentioned being among trees as their “go-to” activity, for example, one participant shared how lovely it was walking through a nearby bush track “and looking at the way the leaves move on the trees.” Other participants shared a similar enjoyment of being amongst trees: “I’m still looking up at the trees and being mindful,” and from another: “I’ve got a creek trail behind me and I’ll go into the trees.” However, the theme of solitude permeated several areas, influencing participants’ emotional, cognitive, spiritual, and social/relational wellbeing.

All interviewees stated that including contemplative practices in their day was important for their wellbeing, and simultaneously expressed a desire to practice it more consistently. For some, their practice involved movement, such as walking mindfully (“my form would be walking in nature”) or running outdoors (“when I was running it was kind of a way for me to meditate”). Another movement-based practice shared by one interviewee was martial arts: “a meditative discipline is good—mine is tai chi.” Others noted that their mindful practice involved reciting a speaking prayer, with one participant sharing, “it’s something I do daily [before going to sleep], and occasionally during the day as well.” Other participants shared that they tended to employ their meditative practice in response to stressful situations: “I tend to do it more when I’m stressed or anxious,” or “I also try and do it when I’m stressed.”

Social enablers

Eleven interviewees indicated that close, supportive relationships helped bolster their wellbeing. For example, one participant described feeling very happy to have social connections to “confide in each other and to support my wellbeing,” and another interviewee shared her enjoyment of “sitting quietly and chatting with friends.” Another participant pointed to the significance of her close relationships: “it’s the sharing of life with people who love me, and I love them immensely.” Several participants specifically mentioned having a small, select circle of friends, with one interviewee noting she had “six dear friends.” Another participant pointed to the supportive nature of her friendship circle: “I don’t really like to be around people too much, but I have a close group of friends and they really help me get through life.” Another interviewee spoke of a preference for intimate interactions with friends, sharing “the last few times I’ve been out, it’s been more one-on-one with my friends.”

Notably, even as participants valued social relationships, all 12 interviewees reported that regular experiences of solitude were an important enabler of their wellbeing. For example, one participant noted that “solitude is something that’s very important for me to maintain some of my sanity and my energy.” Others emphasized that “alone time is very important” and that “it’s really important that I stay with myself.” Participants actively sought time alone, noting that “solitude is built into my everyday life” and “I do a lot of things with myself, just by myself.” Another noted “I’m quite happy to go away in the middle of the bush by myself and camp for a week with one of my dogs, and I’m in bliss.”

Participants spoke to the challenge of harmonizing a desire for social engagement with their need for solitude, especially for the eight more extraverted participants. One noted, “I get a lot of invitations, and I always feel obligated that I need to catch up with this person, and this person and this person […] but now I’m like, no, I’ve had one of those weeks when I need to go home.” Another contrasted loving times to connect with others, but also that “I think I would get really overwhelmed if I did not have that time where I could just turn away.” Participants insightfully understood their own nature, with one noting “I’m a gregarious and outgoing person […] I’m open and direct but I find social interactions exhausting.” Despite valuing other people, one participant shared “I always feel like I need a bit of time to myself, even away from my partner” and another noted “I really value talking [to my family] but I really value my solitude as well.”

Seven interviewees identified the need to consciously and deliberately choose with whom they spend time. These participants described how making more deliberate choices around their contact with others was beneficial for their wellbeing, for instance, “I’ve learned to let go of certain relationships that don’t improve my wellbeing.” These conscious choices extended to “[keeping] very select people in my life,” or to excluding people: “relationships that were having a negative influence on my mood or on my person I have just eliminated or cut down to a bare minimum, and I just see those people when I need to.”

Personal characteristics

Participants also spoke to several personal characteristics that they believed helped them experience wellbeing. Four interviewees spoke of being naturally optimistic and hopeful. Most expressed optimism/hope as a beneficial enabler of their wellbeing; for instance, “I have enormous hope and hope is so important,” and “I’m a naturally very positive person.” However, one interviewee noted some mixed feelings about being optimistic: “sometimes I think it’s good that I always think positively and optimistically, but sometimes I think that I’m not really in the world—I’m in my own world.”

Eight participants referred to meaning as important to their wellbeing and expressed through different areas of life. For instance, one interviewee revealed that a sense of meaning was elicited through religion/spirituality: “my religion is a satisfactory and adequate provider of meaning and purpose in my life.” Other participants spoke of deriving meaning through their work; for example, one interviewee noted “that’s why I do what I do, and I feel really clear about that, because that’s aligned with my meaning statement.” Another participant spoke of feeling a sense of meaning through helping others: “there’s no denying that sense of this is what I’m here for,” while another interviewee described meaning as a driving force in her life: “that’s the overarching thing.” Another area where meaning was embodied was through close relationships: “what provides the most meaning for me is the loving, supportive relationships that I have.”

Barriers of wellbeing

The third key theme to emerge was issues that challenge participants’ wellbeing. Two primary sub-themes emerged: physical health issues and being able to say “no”, along with a series of other issues that were particular to specific participants.

Physical health issues

Six interview participants shared how physical health concerns had been affecting their overall wellbeing, for instance, “I’m getting to the bottom of a few health issues I’ve had, and I think that’s really going to take [my wellbeing] to the next level,” and “I got some bronchial infection […] so I would really like to improve that.” Seven interviewees expressed a desire to improve their physical health in more general terms, “but with exercise I can’t seem to bring that together quite so well, so I find that a real challenge.”

The challenge of saying no

Eight participants specifically reported having difficulty in saying “no” to requests for their time. For example, participants noted: “I’m not very good at saying no, I think I like to please people. I definitely find that hard,” or “I’m so bad at this!” One interviewee pointed to the emotional discomfort inherent in this challenge: “if you always say yes to everything, (but) you feel bad if you say no.” This challenge was noted across work and social domains.

While being able to say “no” was perceived as a challenge, six interviewees shared how this ability had improved over time with ongoing practice, for instance one noted, “that’s something I definitely have to practice and I’m glad, because you do work better with a sharper knife,” and another: “that’s a work in progress but I would say that I’m pretty good at it and much better than I used to be.” One participant noted how through learning to say “no” she had also learnt “I actually don’t have to explain myself.” One participant pointed to this practice making a difference in her wellbeing: “I’ve gotten a lot better at that over the years, before I used to be like ‘oh, okay’ and just sacrifice my alone time for other people, but now it’s like nah!.” Other interviewees shared strategies that they had developed, such as “if I say no, I mean no; if I’m not sure, I’ll say no.” Another noted:

“I just use Spoon theory. It’s where you wake up every morning and you’ve got so many spoons, and it might take a spoon to have a shower, and a spoon to complete a certain task. And every morning when you wake up you don’t always have the same amount of spoons. So, I’ve learnt to say I don’t have the spoons for it.”

Social aspects also appeared in the challenge of saying “no.” Five participants expressed how saying “no” was especially challenging when it involved helping loved ones and close friends. For instance, one interviewee described not being able to take on more things, but still agreeing to help friends or family at a personal cost: “I maybe have to sacrifice my sleeping time, or I forget eating sometimes.” Another participant shared: “the only time I won’t say no when I really want to, is if it’s related to the kids.” One interviewee explained how saying “no” also involved saying “no” or “not yet” to herself: “I’m interested in a million different things and it’s really hard […] for me to say to myself well I can put that on my list, this isn’t the right time to do it, let’s just wait, stay focused.”

Other barriers

Participants also noted a variety of other barriers. One stress-inducing situation described by two interviewees was the sense of having too much on one’s plate. For example, one participant shared “I don’t deal with having to do a lot of things at the same time—that really stresses me out.” Similarly, another interviewee noted “if there’s one big simple task that takes 10 h, and ten smaller tasks that take 1 h each, I’d be a lot more stressed with the ten smaller tasks.” Other participants described having developed or adopted different strategies to help manage demands. For instance, one participant shared how she paced herself instead of “jumping in at the deep end and getting myself in a bit of a fix,” while another reported taking affirmative action in response to her stress: “I shift more toward getting goals achieved rather than focusing on reducing my stress, if I’m a bit stressed I may as well channel it into something productive.”

Another challenge mentioned by participants was having strong emotional responses. For instance, one participant shared: “[the other person] is fine in about thirty seconds, and it really impacts me for a long time, I feel really shaken up by it and it takes me a long time to calm down from things.” Another participant noted that their family “say to me that I’m always really emotional when I was young, and I’m still quite emotional now.” Additionally, two participants shared how strong feelings of empathy could impact their wellbeing at times. For instance, one interviewee reported feeling drained after being in crowded spaces: “I can go to a shopping center, and I need to get out after a while.” Another participant described being able to manage her empathetic responses through being alone “because I don’t feel like I’m carrying other people’s stuff.”

Awareness of and interactions with mental health

Beyond the three main themes that emerged, additional insights emerged from participant reflections on their growing awareness of SPS and experiences with anxiety and depression. First, growing knowledge and awareness of the SPS trait seemed to increasingly be influencing participants’ wellbeing. For ten interviewees, their first awareness of SPS was through participation in the broader Wellbeing and Highly Sensitive Person study (Black and Kern, 2020. Personality and flourishing: exploring Sensory Processing Sensitivity and wellbeing in an Australian adult population (unpublished manuscript)). One interviewee expressed how learning about SPS had improved her wellbeing: “what has improved my wellbeing, being highly sensitive, is also the awareness of the positive aspects of the trait.” Participants anticipated that learning about the SPS trait would be beneficial to their wellbeing, noting for example, “it will probably alert me to take care of myself more,” another stated “this makes sense, and to be so much kinder to myself and respectful to myself,” while another shared “it will help me be more aware and not so hard on myself if I’m not coping in certain environments.” For some participants, their awareness and knowledge of SPS pointed to growing self-acceptance. For example, one interviewee shared having some prior negative perceptions about the trait, but that she had “learnt to recognize that it has positive qualities […] so I’ve learnt to accept that about myself and be more comfortable with it.” Another participant echoed this view: “knowing that sometimes how I’m feeling is due to the higher sensitivity and it’ll pass, and it’s natural, then it’s helped me separate out the anxiety from sensitivity.”

One participant directly pointed to the mismatch between their sensitivity and the extravert-centric Australian culture, noting “I don’t always like to be in a very loud environment, and the Australian culture is more people are outgoing than introverted, so I’m kind of changing myself to adapt to the culture.” Other interviewee accounts were less direct, but nonetheless suggestive of the mismatch between the surrounding culture and their sensitivity, reflecting self-blame. For example, “there’s like a desire to not be sometimes so sensitive. Cause it does make it hard, compared to some other people, to care less about certain things, and be more confident about certain things.” Another participant shared, “So that’s a challenge that I’ve always dealt with and always thought, well why don’t I have as much consistent energy as other people?[…] I’m definitely going to read up on it because that goes a long way to explain that. That would be a real relief for me.”

Second, nine interviewees shared how they had experienced anxiety and/or depression in the past. One participant noted for instance, “I’ve had poor wellbeing, a little bit of anxiety, and I’ve come to understand why,” and another shared “I went through a period where I had depression and anxiety, for about two to three years.” Interviewees also shared how they continued to utilize strategies that had assisted their recovery, for example, one reported “I’m pretty good at identifying warning signs […] and I’m much better at dealing with those warning signs early.”

Discussion

As human beings, many of us seek wellbeing, yet the experience of wellbeing is not the same for everyone—it can be influenced by a range of individual and cultural factors (Khaw and Kern, 2014; Lawn et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018). Predominant characteristics of high-SPS individuals (e.g., Aron, 1996, 2004, 2011) run counter to broader social discourses around wellbeing that dominate WEIRD cultures such as Australia. Indeed, SPS typically is portrayed as a negative characteristic that sets individuals up for a range of illbeing outcomes (e.g., Bakker and Moulding, 2012; Booth et al., 2015; Listou Grimen and Diseth, 2016; Meyerson et al., 2019). Yet despite this misfit, some high-SPS individuals do experience high levels of wellbeing ((Black and Kern, 2020. Personality and flourishing: exploring Sensory Processing Sensitivity and wellbeing in an Australian adult population (unpublished manuscript); Sobocko and Zelenski, 2015). Using semi-structured interviews, this study investigated idiographic conceptions and experiences of wellbeing within high-SPS individuals living in Australia. While the findings do not necessarily generalize to people beyond the study, these idiographic case studies provide insights into individual experiences of wellbeing, providing richer descriptions of how some individuals are able to successfully navigate clashes between their personality and the social context in which they live.

Idiographic conceptions of wellbeing

The past few decades have brought considerable theory, research, and practice focused on understanding and building subjective wellbeing. While some work has considered lay conceptions (e.g., Bharara et al., 2019; Ryff, 1989b; Wong et al., 2011), many of the existing wellbeing models either are based upon academics’ theories (e.g., Huppert and So, 2013; Martela and Sheldon, 2019; Seligman, 2011), or arise from patterns across groups of people (e.g., Cummins, 1998; Diener et al., 1985). The former is inherently influenced by the cultural norms and experiences in which the academic resides, and the latter prioritizes consistent patterns at the expense of understanding individual experiences that may differ from the majority. The current study complements other approaches by adding depth and insights from the perspectives of individuals who identify with personality characteristics that sets them apart from the norm.

Notably, participants conceptualized wellbeing as multi-dimensional in nature, aligning with many contemporary models of wellbeing (Disabato et al., 2020; Huppert and So, 2013; Keyes, 2002; Rusk and Waters, 2015; Ryff, 1989a; Seligman, 2011). Interestingly, participants emphasized the importance of balance or harmony across different dimensions. Similar perceptions of balancing and harmonizing wellbeing dimensions were noted in a study which investigated wellbeing perspectives of Australian young people and youth workers (Bourke and Geldens, 2007). The question of how much or how little of each wellbeing component might be needed (for people to thrive) generally goes unacknowledged in current wellbeing literature. Future studies might consider the extent to which balance and harmony are specific to highly sensitive individuals or might be true of other individuals as well.

In addition, several wellbeing enablers were spontaneously reported during interviews: balance/harmony between wellbeing dimensions; connecting with nature; low-intensity positive emotions; self-awareness; self-acceptance; and optimism and hope. These findings highlight the advantage of idiographic approaches (like the current study), which can provide valuable insights that are often not seen in quantitative studies.

Almost all existing models of subjective wellbeing include an emotional dimension, with scales specifically focusing on high-arousal emotions. Indeed, the positive emotion language on many wellbeing measures (e.g., PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) focuses on high-energy, high-intensity positive emotions (Lim, 2016). The language of these questions fails to incorporate the full range of positive emotions that are available to people, which can subtly imply that low-intensity positive emotions (e.g., contentment, peacefulness, calmness) are either not valid, or do not contribute to wellbeing. In contrast, participants suggested that low-intensity positive states (calm, peaceful, relaxed) are highly valued aspects of high-SPS individuals’ wellbeing. While our results cannot be generalized across broader populations, they suggest that to capture a full range of individual experiences, measures should include both high- and low-valence emotions, and not assume that a person lacks wellbeing simply because they are not excited, enthusiastic or joyful. Indeed, valuing and desiring low-intensity positive emotions, and meeting these ideal levels, has been shown more beneficial to health (predicting fewer physical health symptoms) than meeting ideal high-intensity emotion levels (Scheibe et al., 2013); our findings support this view.

Strategies for staying well despite cultural norms

Large surveys can provide average levels of wellbeing, which are often generalized across a population (Eckersley, 2016), but these surveys are unable to tell us the associated practices that people use to foster their wellbeing. Qualitative explorations—such as ours—provide rich data that can answer the what, how, and when of individual wellbeing (Hefferon et al., 2017). Our findings suggest that, within the extravert-dominant Australian culture, high-SPS individuals are able to instinctively create a unique constellation of “good things” that contribute to their wellbeing. Our findings can help to normalize a sensitive orientation and offer some measure of validation to high-SPS individuals who live within WEIRD countries.

By far, the most notable enabler of wellbeing was actively choosing solitude. In their initial series of studies into the SPS trait, Aron and Aron (1997) noted a preference among high-SPS individuals for time spent alone: our results support their findings and provide a foundation for linking this dimension with high-SPS wellbeing. Scholars and researchers have long discussed the benefits of solitary experiences for wellbeing (Merton, 1958; Montaigne, 1877; Zimmerman, 1799). Recent research further demonstrates the benefits of solitude for wellbeing (Leary et al., 2003; Leontiev, 2019; Long and Averill, 2003; Nguyen et al., 2018), yet this seemingly important wellbeing component does not appear in any of the commonly used wellbeing models or measures (e.g., Diener et al., 1985; Linton et al., 2016; Ryff, 1989a). Future studies might benefit from focusing on these elements, identifying for whom, and under what conditions, they are useful.

Solitude may provide the time and space for self-awareness, self-acceptance, and self-compassion, aspects that participants pointed towards being helpful for wellbeing. Our findings are consistent with the literature that generally associates dispositional self-awareness with high levels of psychological wellbeing, and views it as a means of alleviating psychological distress (Gu et al., 2015; Sutton, 2016). Our results also align with existing research showing positive associations between self-acceptance and psychological wellbeing (Lindfors et al., 2006; Ryff, 1989a, 2014). Acknowledging and accepting both good and bad aspects of the self are key attributes of self-acceptance (Ryff, 1989a) and these were reflected in participant reports. Cultivating self-compassion has been shown to positively predict wellbeing (Neff et al., 2007) and greater life satisfaction (Neff et al., 2008), and our findings lend support to this literature.

The experience of connecting with nature was important to at least half the interviewees, many of whom shared that being alone in nature was their preference, rather than in the company of others. This aligns with studies pointing to the restorative effect of nature on wellbeing (Korpela and Staats, 2014), and positive associations between wellbeing, mindfulness, and nature connectedness (Capaldi et al., 2014; Howell et al., 2011).

Participants also pointed to a complicated balance between using social relationships to support wellbeing, and when relationships became detrimental to their wellbeing. These themes align with research associating greater individual wellbeing with harmonious relationships (typified by high warmth and low levels of conflict; Sherman et al., 2006) and the fulfillment of the psychological need for relatedness (Patrick et al., 2007; Ryan and Deci, 2017). Conversely, conflicted (Sherman et al., 2006) or poor quality (Hartup and Stevens, 1999) relationships have been associated with low levels of individual wellbeing.

Highly sensitive individuals in WEIRD countries do not fit neatly within the wider social and cultural context (Aron, 1996, 2004) in which they live, and high-SPS individuals may try to navigate social situations as expected, but find the situation overwhelming and oppressive, resulting in anxiety and self-blame. Interestingly, interview participants mostly did not explicitly mention feeling a mismatch between their innate sensitivity and the surrounding extravert-centric culture. However, when sharing their experiences around becoming aware of the SPS trait and its associated benefits, multiple responses did suggest this mismatch, particularly pointing to blaming themselves and wondering why they seem to be different than others. Indeed, learning about their sensitivity provided an explanation for these differences, which several interviewees found empowering. By understanding that the characteristics of SPS may impact how the person experiences and relates to the world, it can provide explanation and support a sense of autonomy. Future research might consider the role that identifying with high-SPS might have upon behaviors and perceptions of wellbeing.

Our participants identified physical health issues, the challenge of saying “no”, and the sense of having too much on one’s plate as barriers to their wellbeing. These perceived barriers are not unique to high-SPS individuals, especially the sense of feeling overwhelmed from too much to do (e.g., Bellezza et al., 2017; Leshed and Sengers, 2011; Skinner and Pocock, 2008). Future studies might benefit from further investigating factors that create a sense of overwhelm, and strategies that effectively decrease this sense for different individuals.

Our findings represent specific individuals living within a specific sociohistorical context. Future studies might benefit from considering other characteristics that could impact the experience of, enablers of, and barriers to wellbeing, for individuals who live in non-WEIRD sub-cultures or cultures, and/or for those who do not fit typical conceptualizations of the happy person. The specific causes and mechanisms of high-SPS wellbeing are beyond the scope of this study but could present a worthwhile focus for future research.

Conclusion

By combining multiple perspectives from individuals high in SPS, the current study provides a richer understanding of how some individuals—those who are high in SPS but also experience high levels of wellbeing—conceive of and create wellbeing. Participants pointed to the importance of considering multiple domains, and the balance amongst those domains, rather than emphasizing greater amounts of specific domains. Participants also pointed to the value of low-arousal positive emotions. They identified emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and social strategies that they engage to stay well despite social pressures. While results cannot be generalized to other groups, the combination of wellbeing contributors and enablers highlight a somewhat unique picture of wellbeing, offering an expanded view of what it means to feel good and function well. We suggest that the results provide key insights into how individuals live well, within the context of friction between their natural personality and the social, cultural, and historic context in which they live. As a whole, this study provides a richer, more sophisticated understanding of the lived experiences of—and pathways to—wellbeing for highly sensitive individuals.

Data availability

The dataset from the 32 themes analyzed in the current study is available at: https://doi.org/10.26188/5e9950060e4d3

References

Allik J (2005) Personality dimensions across cultures. J Personal Disord 19(3):212–232

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Aron EN (1996) The highly sensitive person: how to thrive when the world overwhelms you. Broadway Books, New York

Aron EN (2004) Revisiting Jung’s concept of innate sensitiveness. J Anal Psychol 49(3):337–367

Aron EN (2011) Psychotherapy and the highly sensitive person: improving outcomes for that minority of people who are the majority of clients [electronic resource]. Taylor and Francis, Hoboken

Aron EN, Aron A (1997) Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. J Personal Soc Psychol 73(2):345–368

Baerger DR, McAdams DP (1999) Life story coherence and its relation to psychological well-being. Narrative Inq 9(1):69–96. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.9.1.05bae

Bakker K, Moulding R (2012) Sensory-processing sensitivity, dispositional mindfulness and negative psychological symptoms. Personal Individ Differences 53(3):341–346

Bellezza S, Paharia N, Keinan A (2017) Conspicuous consumption of time: when busyness and lack of leisure time become a status symbol. J Consum Res 44(1):118–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw076

Benet-Martínez V (2006) Cross-cultural personality research: conceptual and methodological issues. In: Robins RW, Fraley C, Krueger RF (Eds.) Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. The Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp. 170–189

Bharara G, Duncan S, Jarden A, Hinckson E (2019) A prototype analysis of New Zealnd adolescents’ conceptualizaations of wellbeing. Int J Wellbeing 9(4):1–25. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v9i4.975

Booth C, Standage H, Fox E (2015) Sensory-processing sensitivity moderates the association between childhood experiences and adult life satisfaction. Personal Individ Differences 87(Dec):24–29

Boterberg S, Warreyn P (2016) Making sense of it all: the impact of sensory processing sensitivity on daily functioning of children. Personal Individ Differences 92(Apr):80–86

Bourke L, Geldens P (2007) What does wellbeing mean? Yout Stud Aust 26(1):41–49

Brindle K, Moulding R, Bakker K, Nedeljkovic M (2015) Is the relationship between sensory processing sensitivity and negative affect mediated by emotional regulation? Aust J Psychol 67(4):214–221

Butler J, Kern ML (2016) The PERMA profiler: a brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int J Wellbeing 6(3):1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.1

Capaldi CA, Dopko RL, Zelenski JM (2014) The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol 5(08 Sept):976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00976

Chiu CY, Chen J (2004) Symbols and interactions: application of the CCC Model to culture, language,and social identity. In: Ng SH, Candlin CN, Chiu CY (eds) Language matters: communication, culture, and identity. City University of Hong Kong Press, Hong Kong, pp. 155–182

Christopher JC (1999) Situating psychological well-being: exploring the cultural roots of its theory and research. J Counseling Dev 77(2):141–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02434.x

Christopher JC, Hickinbottom S (2008) Positive psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory Psychol 18(5):563–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354308093396

Cooke PJ, Melchert TP, Connor K (2016) Measuring well-being: a review of instruments. Counseling Psychologist 44(5):730–757

Crisp R (Ed.) (2014) Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Cummins RA (1998) The second approximation to an international standard for life satsifaction. Soc Indic Res 43(3):307–334. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006831107052

Davidson B, Gillies RA, Pelletier AL (2015) Introversion and medical student education: challenges for both students and educators. Teach Learn Med 27(1):99–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2014.979183

Delle Fave A, Wissing M, Brdar I, Vella-Brodrick D, Freire T (2013) Cross-cultural perceptions of meaning and goals in adulthood: their roots and relation with happiness. In: Waterman A (ed.) The best within us: positive psychology perspectives on eudaimonia. APA, Washington DC, pp. 227–247

DeNeve KM, Cooper H (1998) The happy personality: a meta analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bull 124(2):197–229

Diener E (2000) Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychologist 55(1):34–43

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The satisfaction with life scale. J Personal Assess 49(1):71–75

Diener E, Oishi S, Lucas RE (2003) Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu Rev Psychol 54:403–425

Disabato, DJ, Goodman, FR, & Kashdan, TB (2020). A hierarchical framework of well-being. PsyArXiv Database [Preprint], Dec 31. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5rhqj

Disabato DJ, Goodman FR, Kashdan TB, Short JL, Jarden A (2016) Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychological Assess 28(5):471–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000209

Eatough V, Smith JA (2017) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Willig C, Stainton-Rogers W (eds.) The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, pp. 193–209

Eckersley R (2016) Is the West really the best? Modernisation and the psychosocial dynamics of human progress and development. Oxf Dev Stud 44(3):349–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1166197

Eckersley R, Cahill H, Wierenga A, Wyn J (2007). Generations in dialogue about the future: the hopes and fears of young Australians. Retrieved from Weston, ACT

Eysenck HJ (1983) I do: your guide to a happy marriage. Century, London

Fleeson W, Malanos AB, Achille NM (2002) An intraindividual process approach to the relationship between extraversion and positive affect: is acting extraverted as “good” as being extraverted? J Personal Soc Psychol 83(6):1409–1422

Frawley A (2015) Happiness research: a review of critiques. Sociol Compass 9(1):62–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12236

Friedman HS, Kern ML (2014) Personality, well-being, and health. Annu Rev Psychol 65:719–742

Fudjack SL (2013) Amidst a culture of noise silence is still golden: a sociocultural historical analysis of the pathologization of introversion. (Master of Social Work), Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts

Fulmer CA, Gelfand MJ, Kruglanski AW, Kim-Prieto C, Pierro A, Higgins ET (2010) On “feeling right” in cultural contexts: how person-culture match affects self-esteem and subjective well-being. Psychological Sci 21(11):1563–1569

Galinha IC, Oishi S, Pereira C, Wirtz D, Esteves F (2013) The role of personality traits, attachment style, and satisfaction with relationships in the subjective well-being of Americans, Portuguese, and Mazambicans. J Cross-Cultural Psychol 44(3):416–437

Goodman FR, Disabato DJ, Kashdan TB, Kaufman SB (2017). Measuring well-being: a comparison of subjective well-being and PERMA. J Posit Psychol, Online(October), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1388434

Greven CU, Lionetti F, Booth C, Aron EN, Fox E, Schendan HE, Homberg JR (2019) Sensory processing sensitivity in the context of environmental sensitivity: a critical review and development of research agenda. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 98(March):287–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.01.009

Grimes JO (2010) Introversion and autism: a conceptual exploration of the placement of introversion on the austism spectrum. (Master of Arts), University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL

Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K (2015) How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clin Psychol Rev 37(April):1–12

Hartup WW, Stevens N (1999) Friendships and adaptation across the life span. Curr Directions Psychological Sci 8(3):76–79

Hefferon K, Ashfield A, Waters L, Synard J (2017) Understanding optimal human functioning-The ‘call for qual’ in exploring human flourishing and well-being. J Posit Psychol 12(3):211–219

Helliwell J, Layard R, Sachs J (2016). World Happiness Report 2016, Update (vol. 1) Helliwell J, Layard R, Sachs J (eds.). Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York

Hendriks T, Warren MA, Schotanus-Dijkstra M, Hassankhan A, Graafsma T, Bohlmeijer ET, de Jong J (2019) How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of well-being. J Posit Psychol 14(4):489–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941

Henjum A (1982) Introversion: a misunderstood ‘individual difference’ among students. Educ Media Int 103(1):39–43

Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan, A (2010a). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466(29). https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a

Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A (2010b) The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci 33(2-3):61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Hone LC, Jarden A, Schofield GM, Duncan S (2014) Measuring flourishing: the impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of wellbeing. Int J Wellbeing 4(1):62–90

Howell AJ, Dopko RL, Passmore HA, Buro K (2011) Nature connectedness: associations with well-being and mindfulness. Personal Individ Differences 51(2):166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037

Huppert FA (2014) The state of wellbeing science. Concepts, measures, interventions, and policies. In: Huppert FA, Cooper CL (eds.) Wellbeing: a complete reference guide. Volume VI: interventions and policies to enhance wellbeing. Wiley Blackwell, Chichester, West Sussex, pp. 1–49

Huppert FA, So TTC (2013) Flourishing across Europe: application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc Indic Res 110(3):837–861

Kern ML, Williams P, Spong C, Colla R, Sharma K, Downie A,… Oades, LG (2019). Systems informed positive psychology. J Posit Psychol, Online(12 July), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

Keyes CLM (2002) The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 43(2):207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Khaw D, Kern ML (2014) A cross-cultural comparison of the PERMA model of well-being. Undergrad J Psychol Berkeley 8(Fall/Spring):10–23

Kitayama S, Markus HR (2000) The pursuit of happiness and the realization of sympathy: cultural patterns of self, social relations, and well-being. In: Diener E, Suh EM (eds.) Culture and subjective well-being. The MIT Press, Boston, pp. 113–161

Koopmann-Holm B, Tsai JL (2014) Focusing on the negative: cultural differences in expressions of sympathy. J Personal Soc Psychol 107(6):1092–1115

Korpela K, Staats H (2014) The restorative qualities of being alone with nature. In: Coplan RJ, Bowker JC (eds.) The handbook of solitude: psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, West Sussex, UK, pp. 351–367

Laajaj R, Macours K, Pinzon Hernandez DA, Arias O, Gosling SD, Potter J, Vakis R (2019) Challenges to capture the big five personality traits in non-WEIRD populations. Sci Adv 5(7):eaaw5226. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw5226

Lawn RB, Slemp GR, Vella-Brodrick DA (2018). Quiet flourishing: the authenticity and well-being of trait introverts living in the West depends on extraversion-deficit beliefs. J Happiness Stud, Online First(01 October), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0037-5

Leary MR, Herbst KC, McCrary F (2003) Finding pleasure in solitary activities: desire for aloneness or disinterest in social contact? Personal Individ Differences 35(1):59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00141-1

Leontiev D (2019). The dialectics of aloneness: positive vs. negative meaning and differential assessment. Counsell Psychol Quarter, Latest Articles(09 July), https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1640186

Leshed G, Sengers P (2011). “I lie to myself that I have freedom in my own schedule: productivity tools and experiences of busyness. Paper presented at the CHI 2011, Vancouver, BC

Lim N (2016) Cultural differences in emotion: differences in emotional arousal level between the East and West. Integr Med Res 5(2):105–109

Lindfors P, Berntsson L, Lundberg U (2006) Factor structure of Ryff’s psychological well-being scales in Swedish female and male white-collar workers. Personal Individ Differences 40(6):1213–1222

Linton M-J, Dieppe P, Medina-Lara A (2016). Review of 99 self-report measures for assessing well-being in adults: exploring dimensions of well-being and developments over time. BMJ Open 6(e010641). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010641

Lionetti F, Aron A, Aron EN, Burns GL, Jagiellowicz J, Pluess M (2018) Dandelions, tulips and orchids: evidence for the existence of low-sensitive, medium-sensitive and high-sensitive individuals. Transl Psychiatry 8(24):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-017-0090-6

Listou Grimen H, Diseth A (2016) Sensory processing sensitivity: factors of the Highly Sensitive Person Scale and their relationships to personality and subjective health complaints. Percept Mot Skills 123(3):637–653

Long CR, Averill JR (2003) Solitude: an exploration of benefits of being alone. J Theory Soc Behav 33(1):21–44

Lu L, Gilmour R (2004) Culture and conceptions of happiness: individual oriented and social oriented SWB. J Happiness Stud 5(3):269–291

Martela F, Sheldon KM (2019). Clarifying the concept of well-being: psychological need satisfaction as the common core connecting eudaimonic and subjective well-being. Rev Gen Pscyhol, Online First(October), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019880886

Mathews G (2012) Happiness, culture, and context. Int J Wellbeing 4(2):299–312. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2.i4.2

McAdams DP, Guo J (2015) Narrating the generative life. Psychological Sci 26(4):475–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614568318

McAdams DP, Olsen BD (2010) Personality development: continuity and change over the life course. Annu Rev Psychol 61(Jan):517–542. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100507

McCrae RR, Costa PT (1991) Adding Liebe und Arbeit: the full Five-Factor model and well-being. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 17(2):227–232

McWilliams N (2006) Some thoughts about schizoid dynamics. Psychoanalytic Rev 93(1):1–24

Meredith PJ, Bailey KJ, Strong J, Rappel G (2016) Adult attachment, sensory processing, and distress in healthy adults. Am J Occup Ther 70(1):1–8

Merton T (1958) Thoughts in solitude. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York

Meyerson J, Gelkopf M, Eli I, Uziel N (2019). Burnout and professional quality of life among Israeli dentists: the role of sensory processing sensitivity. Int Dental J, Early View(Septmeber), https://doi.org/10.1111/idj.12523

Montaigne M (1877) Of solitude (C. Cotton, Trans.). In: Hazlitt WC (ed.) Essays of Michel de Montaigne. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA (online)

Neal JA, Edelmann RJ, Glachan M (2002) Behavioural inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression: is there a specific relationship with social phobia? Br J Clin Psychol 41(4):361–374

Neff KD, Pisitsungkagarn K, Hsieh Y-P (2008) Self-compassion and self-construal in the United States, Thailand, and Taiwan. J Cross-Cultural Psychol 39(3):267–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022108314544

Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick KL (2007) An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. J Res Personal 41(4):908–916

Nguyen TT, Ryan RM, Deci EL (2018) Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 44(1):92–106

Patrick H, Knee CR, Canevello A, Lonsbary C (2007) The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: a self-determination theory perspective. J Personal Soc Psychol 92(3):434–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434

Pierre J (2010) The borders of mental disorder in psychiatry and the DSM: past, present, and future. J Psychiatr Pract 16(6):375–386. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000390756.37754.68

Pluess M, Assary E, Lionetti F, Lester KJ, Krapohl E, Aron EN, Aron A (2018) Environmental sensitivity in children: development of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale and identification of sensitivity groups. Developmental Psychol 54(1):51–70

QSR International Pty Ltd. (Released 2015). NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 11): QSR International Pty Ltd.

Rusk RD, Waters L (2015) A psycho-social system approach to well-being: empirically deriving the five domains of positive functioning. J Posit Psychol 10(2):141–152

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2017) Self-determination theory. Guilford Press, New York

Ryff CD (1989a) Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Personal Soc Psychol 57(6):1069–1081

Ryff CD (1989b) In the eye of the beholder: views of psychological well-being among middle-aged and older adults. Psychol Aging 4(2):195–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.195

Ryff CD (2014) Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom 83(1):10–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

Ryff CD, Singer BH (1996) Psychological well-being: meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychother Psychosom 65(1):14–23

Scheibe S, English T, Tsai JL, Carstensen LL (2013) Striving to feel good: ideal affect, actual affect, and their correspondence across adulthood. Psychol Aging 28(1):160–171

Seligman M (2011) Flourish. A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. William Heinemann Random House Australia Pty Ltd, North Sydney

Sherman AM, Lansford JE, Volling BL (2006) Sibling relationships and best friendships in young adulthood: warmth, conflict, and well-being. Personal Relatsh 13(2):151–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00110.x

Skinner N, Pocock B (2008) Work-life conflict: is work time or work overload more important? Asia Pac J Hum Resour 46(3):303–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411108095761

Smillie LD (2013) Why does it feel good to act like an extravert? Soc Personal Psychol Compass 7(12):878–887

Smillie LD, DeYoung CG, Hall PJ (2015) Clarifying the relation between extraversion and positive affect. J Personal 83(5):564–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12138

Smillie LD, Wilt J, Kabbani R, Revelle W (2016) Making a mark on ones milieu: why it feels good to be and act extraverted. Personal Individ Differences 101:515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.298

Smith JA (1996) Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychol Health 11(2):261–271

Smith JA (2017) Interpretive phenomenological analysis: getting at lived experience. J Posit Psychol 12(3):303–304

Smith JA, Eatough V (2011) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Lyons E, Coyle A (eds.) Analysing qualitative data in psychology. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, pp. 35–50

Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M (2009) Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research. Sage, London

Smith JA, Jarman M, Osborn M (1999) Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Murray M, Chamberlain K (eds.) Qualitative health psychology. Sage, London, pp. 218–240

Sobocko K, Zelenski JM (2015) Trait sensory-processing sensitivity and subjective well-being: distinctive associations for different aspects of sensitivity. Personal Individ Differences 83(Sept):44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.045

Steadman P (2008) ICD-11 and DSM-V: time to revisit the introversion/extroversion debate? BJ Psych Bull 32(6):233–233. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.32.6.233

Steel P, Schmidt J, Shultz J (2008) Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bull 134(1):138–161

Stephens NM, Townsend SSM, Markus HR, Phillips LT (2012) A cultural mismatch: independent cultural norms produce greater increases in cortisol and more negative emotions among first-generation college students. J Exp Soc Psychol 48(6):1389–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.008

Sun J, Kaufman SB, Smillie LD (2018) Unique associations between Big Five personality aspects and multiple dimensions of well-being. J Personal 86(2):158–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12301

Sun J, Stevenson K, Kabbani R, Richardson B, Smillie LD (2017) The pleasure of making a difference: perceived social contribution explains the relation between extraverted behavior and positive affect. Emotion 17(5):794–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000273

Sutton A (2016) Measuring the effects of self-awareness: construction of the self-awareness outcomes questionnaire. Eur J Psychol 12(4):645–658. 10.5964%2Fejop.v12i4.1178

The Treasury New Zealand Government. (2019). The Wellbeing Budget 2019. Wellington, NZ: The Treasury New Zealand Government Retrieved from https://treasury.govt.nz/publications/wellbeing-budget/wellbeing-budget-2019-html

Triandis HC, Suh EM (2002) Cultural influences on personality. Annu Rev Psychol 53(Feb):133–160. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135200

Tsai JL (2007) Ideal affect: cultural causes and behavioral consequences. Perspect Psychological Sci 2(3):242–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00043.x