-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

I. PELC, C. HANAK, I. BAERT, C. HOUTAIN, P. LEHERT, F. LANDRON, P. VERBANCK, EFFECT OF COMMUNITY NURSE FOLLOW-UP WHEN TREATING ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE WITH ACAMPROSATE, Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 40, Issue 4, July/August 2005, Pages 302–307, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agh136

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Aims: To measure the effect of community nurse follow-up on abstinence and retention rates in the outpatient treatment of alcohol-dependent patients treated with acamprosate. Methods: Recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients were prescribed acamprosate for 26 weeks and randomized to either physician-only follow-up, or physician plus regular visits from a community nurse. Drinking behaviour in the next 26 weeks was assessed at monthly visits to non-blind clinicians. Results: The cumulative abstinence duration proportion (CADP) was significantly longer in (P = 0.03) the subjects who had received community nurse support (0.57) than in those who had not (0.39). This might, in part, be an artefact of the higher retention rate among those followed up by the nurse, in that, the method of calculating CADP allocates 100% days of drinking for the month before a failed attendance. Differences favouring nurse in the follow-up were seen for time to first drink, and clinical global impression. Conclusions: For recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients treated with acamprosate, follow-up by a community nurse improves patient retention and probably also improves the 6-month drinking outcome.

(Received 6 April 2004; first review notified 9 May 2004; in final revised form 21 December 2004; accepted 22 December 2004)

INTRODUCTION

The utility of a psychosocial follow-up in optimizing the outcome in rehabilitation programmes for alcohol dependence is well documented (Miller and Wilbourne, 2002). An important objective is to maintain the patients on treatment, since this is a major determinant of long-term abstinence (Baekeland and Lundwall, 1975; Hu et al., 1997; Mattson et al., 1998). In addition, pharmacotherapy is also useful, particularly, naltrexone and acamprosate (Garbutt et al., 1999). The benefit of naltrexone may differ according to the type of psychosocial support used (O'Malley et al., 1992; Heinälä et al., 2001; Balldin et al., 2003). In contrast, in the randomized clinical trials performed with acamprosate, psychosocial support has not been defined by protocol. Although this design allowed the investigators to use whatever kind of psychosocial support was in use in their clinics, and thus demonstrate that the benefit of acamprosate can be observed across a variety of routine psychosocial procedures, it did not address the potential interactions between acamprosate and a specific form of psychosocial support. In subsequent open-label observational studies with acamprosate, subjects have been stratified according to the type of psychosocial support used (Ansoms et al., 2000; Pelc et al., 2002; Soyka et al., 2002). De Wildt et al. (2002) and Hammerberg et al. (2004) randomly allocated patients receiving acamprosate to different forms of psychotherapy in the outpatient phase. This did not reveal any difference in the efficacy of acamprosate according to the type or intensity of psychosocial treatment used. Instead of testing once again the effect of psychotherapy per se, we wished to test whether a follow-up by a nurse could enhance the outcomes during acamprosate therapy.

METHODS

This study was an open comparative randomized study performed in the addiction clinic in the Psychiatry Department of the Brugmann University Hospital in Brussels. Enrolment in the study began in April 1997, and the last patient completed the 6-month treatment period in March 1998.

Patients

One hundred patients were recruited from those undergoing inpatient alcohol detoxification programme for 3 weeks in the above clinic. Patients were included if they lived in the Brussels region, met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and were aged between 18 and 65 years. The patients had completed 1 week of abstinence at the time of inclusion in the study.

The following were the exclusion criteria: other drug dependencies (except nicotine), renal insufficiency, pregnancy or breast feeding, previous treatment with acamprosate, hospitalization for treatment of an Axis 1 psychiatric disorder, participation in any other study in the previous month, use of any unregistered experimental treatment and inability or ineligibility to provide an informed consent. There were no forbidden concomitant medications, with the exception of other abstinence-promoting drugs. Moreover, if it was anticipated that hospitalization for any reason beyond the 3 week inpatient detoxification would be required, the patient was excluded.

Randomization and treatment

Subjects were screened when they were admitted for a 3 week acute detoxification programme in the addiction unit of the Brugmann University Hospital. Once the patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria had completed 1 week of abstinence, they were randomized into two groups, with or without a nurse follow-up. A computer-generated code was created before the beginning of the study and held by an independent third party. Investigators telephoned the centre before the inclusion of each subject, to obtain a randomization number defining the group to which the patient was to be assigned. Investigators had no access to the source code.

After detoxification, the patients were discharged and subsequently followed up as outpatients for the study duration. In case of a severe relapse (defined as a relapse requiring rehospitalization), the treating physician could readmit the patient. Treatment with acamprosate was initiated during the first 7 days of abstinence and continued for 26 weeks. The dose administered was 1998 mg/day if their body weight exceeded 60 kg (two 333 mg tablets t.i.d.) or a dose of 1332 mg/day if their body weight was <60 kg (four tablets: two in the morning, one at midday and one in the evening). The moment of randomization and the initiation of acamprosate treatment after 1 week's abstinence during the inpatient detoxification programme was taken as the beginning of the study period. Use of naltrexone or disulfiram was not permitted during the study period. The patients could receive any appropriate psychotherapeutic procedure deemed useful by the hospital physician.

The patients returned to the hospital outpatient clinic at 4 and 6 weeks, then every 4 weeks to assess the efficacy, safety and compliance to treatment. Patients in the ‘no nurse’ follow-up group were invited to consult their general practitioner whenever necessary. The latter received no specific instructions on how the patients should be managed. The management of the no nurse group corresponded to the standard rehabilitation care of alcohol dependence in the Brugmann University Hospital. Patients in the nurse follow-up group could also consult their general practitioner if required.

In the nurse follow-up group, a community nurse, who contacted the patient at least once a week by telephone, closely monitored each patient. One individual filled the role. She was available by telephone 24 h a day, 7 days a week and could arrange ad hoc telephone calls to the patient by mutual agreement. Home visits could be made at the initiative of the patients or the community nurse, with the patient's consent, whenever considered useful. The community nurse also coordinated a follow-up at the hospital outpatient clinic and by the general practitioner, and could accompany the patient to these consultations if desired. She did not specifically recommend referral for other therapies.

The community nurse was qualified in community health, experienced in the care of alcohol-dependent patients and trained in the relevant psychosocial support procedures used at the study centre.

Data collection

At the time of inclusion, demographic data (age, gender, marital status, occupational status and living situation) were collected. A medical history and a history of alcohol-related behaviour and pathology was recorded, including data on drinking patterns, duration of drinking and previous treatments for alcohol-related problems. Physical examination and standard laboratory tests were performed at the time of inclusion and at study end. Alcohol consumption during the previous month was documented at each study visit, but the clinicians who did this were not blinded to the treatment group. Patients were asked about adverse events at each study visit.

Outcome measures

The primary efficacy variables were retention in the study protocol and abstinence. Retention in the trial was defined as the total study duration for completers, and as the time to dropout for patients who left the trial prematurely. Abstinence was defined as no consumption of alcohol, and relapse as any alcohol consumption since the previous study visit. If information was unavailable at any study visit, the entire preceding period was counted as non-abstinent.

Abstinence was quantified as the cumulative abstinence duration over the study, expressed as a proportion of the total study length of 26 weeks (CADP), and this was taken as the primary efficacy criterion. Secondary endpoints were the proportion of patients continuously abstinent throughout the study period (AAP), the time to first drink, and the time to stable recovery (defined as the moment from when abstinence is continuously observed until the study end).

Other secondary outcome variables measured in the study were compliance with acamprosate since the previous visit and clinical global impression (CGI) rated at the end of the study. Compliance was determined by the investigator keeping note of the unused study medication and empty medication packs returned to the study centre by the patients.

Statistical analysis

The study population analysed was an intention to treat population, defined as all randomized patients having taken at least one dose of drug and for whom at least one post-baseline measure of alcohol consumption was available.

The principal outcome criterion (CADP) was compared between the treatment groups using Student's t-test. One-tailed comparisons were used, since it was considered that efficacy with an extensive follow-up could not be worse than a minimal social support. A P-value of 0.05 was considered as significant. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test. To assess simultaneously the effect of treatment on the outcome with the effect of other baseline determinants of outcome, a general least squares multivariate linear regression analysis was used.

A priori power calculations were made to determine the number of patients to be included, assuming an α risk of 0.05 and a β risk of 0.25, and an anticipated difference of at least 40% between the arms (considered as clinically relevant). A variation coefficient of 80 was used, based on data obtained in the previous clinical trials of acamprosate in alcohol dependence with similar outcome determinations. These calculations predicted that an inclusion of 50 patients per arm should be sufficient to detect the desired difference in CADP.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Hong Kong Amendment), Good Clinical Practice (European Guidelines) and pertinent Belgian legal and regulatory requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Brugmann University Hospital of Brussels.

RESULTS

Patient flow and characteristics

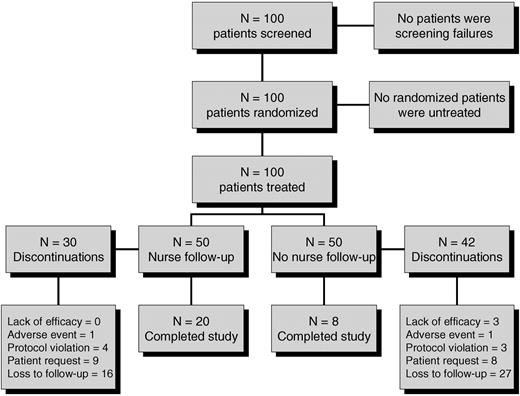

One hundred patients were included in the study and randomized. There were seven protocol violations: four in the nurse follow-up group (two patients who did not complete the 3 week inpatient detoxification programme, one patient who did not comply with the protocol and one patient for whom a prescription of disulfiram was deemed necessary) and three in the no nurse follow-up group (two patients who did not complete the detoxification programme and one case of poor compliance). Twenty-eight patients completed the study: 20 in the nurse follow-up group and eight in the no nurse follow-up group. The patient flow through the study is presented in Fig. 1. Baseline demographic variables (Table 1) were comparable in the patients receiving the nurse follow-up and those who did not. The average age of the patients was 43 years and 78% were male. No statistically significant inter-group difference was observed for any item. Similarly, no differences were seen in the severity or history of drinking. Most of the patients (82%) were regular smokers.

Demographic and clinical variables at baseline

| Variable . | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.5 ± 8.8 | 43.1 ± 7.2 | ||

| Gender M/F (%) | 74/26 | 82/18 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (%) | 34 | 40 | ||

| Married (%) | 20 | 16 | ||

| Divorced (%) | 38 | 42 | ||

| Widowed (%) | 8 | 2 | ||

| Educational status | ||||

| Primary (%) | 36 | 28 | ||

| Secondary (%) | 40 | 48 | ||

| University (%) | 24 | 24 | ||

| Family history (%) | 58 | 68 | ||

| DSM IV score | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | ||

| Number of drinks per day | 20.4 ± 13.6 | 17.8 ± 8.6 | ||

| Number of previous withdrawals | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | ||

| Years of alcohol dependence | 13.1 ± 9.2 | 15.1 ± 10.1 | ||

| Variable . | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.5 ± 8.8 | 43.1 ± 7.2 | ||

| Gender M/F (%) | 74/26 | 82/18 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (%) | 34 | 40 | ||

| Married (%) | 20 | 16 | ||

| Divorced (%) | 38 | 42 | ||

| Widowed (%) | 8 | 2 | ||

| Educational status | ||||

| Primary (%) | 36 | 28 | ||

| Secondary (%) | 40 | 48 | ||

| University (%) | 24 | 24 | ||

| Family history (%) | 58 | 68 | ||

| DSM IV score | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | ||

| Number of drinks per day | 20.4 ± 13.6 | 17.8 ± 8.6 | ||

| Number of previous withdrawals | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | ||

| Years of alcohol dependence | 13.1 ± 9.2 | 15.1 ± 10.1 | ||

Quantitative data are presented as mean (SD) values.

Demographic and clinical variables at baseline

| Variable . | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.5 ± 8.8 | 43.1 ± 7.2 | ||

| Gender M/F (%) | 74/26 | 82/18 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (%) | 34 | 40 | ||

| Married (%) | 20 | 16 | ||

| Divorced (%) | 38 | 42 | ||

| Widowed (%) | 8 | 2 | ||

| Educational status | ||||

| Primary (%) | 36 | 28 | ||

| Secondary (%) | 40 | 48 | ||

| University (%) | 24 | 24 | ||

| Family history (%) | 58 | 68 | ||

| DSM IV score | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | ||

| Number of drinks per day | 20.4 ± 13.6 | 17.8 ± 8.6 | ||

| Number of previous withdrawals | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | ||

| Years of alcohol dependence | 13.1 ± 9.2 | 15.1 ± 10.1 | ||

| Variable . | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.5 ± 8.8 | 43.1 ± 7.2 | ||

| Gender M/F (%) | 74/26 | 82/18 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (%) | 34 | 40 | ||

| Married (%) | 20 | 16 | ||

| Divorced (%) | 38 | 42 | ||

| Widowed (%) | 8 | 2 | ||

| Educational status | ||||

| Primary (%) | 36 | 28 | ||

| Secondary (%) | 40 | 48 | ||

| University (%) | 24 | 24 | ||

| Family history (%) | 58 | 68 | ||

| DSM IV score | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | ||

| Number of drinks per day | 20.4 ± 13.6 | 17.8 ± 8.6 | ||

| Number of previous withdrawals | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | ||

| Years of alcohol dependence | 13.1 ± 9.2 | 15.1 ± 10.1 | ||

Quantitative data are presented as mean (SD) values.

Efficacy measures

CADP was higher in those subjects who received the nurse follow-up than in those who did not: 0.55 (SD: 0.37) in the nurse follow-up group and 0.39 (SD: 0.34) in the no nurse follow-up group. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.03).

A significant difference advantage for the nurse follow-up group was observed for treatment retention as well as for the drinking-related secondary outcome variables and for the CGI (Table 2).

Secondary outcome measures in the CAPRISO study

. | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute abstinence | 16% | 32% | <0.05 |

| Time to first drink | 67 days | 81 days | <0.05 |

| Treatment retention | 24% | 46% | <0.05 |

| Clinical Global Impression | <0.05 | ||

| Marked or slight improvement | 11 | 25 | |

| No change | 11 | 13 | |

| Slightly or much worse | 28 | 12 |

. | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute abstinence | 16% | 32% | <0.05 |

| Time to first drink | 67 days | 81 days | <0.05 |

| Treatment retention | 24% | 46% | <0.05 |

| Clinical Global Impression | <0.05 | ||

| Marked or slight improvement | 11 | 25 | |

| No change | 11 | 13 | |

| Slightly or much worse | 28 | 12 |

Secondary outcome measures in the CAPRISO study

. | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute abstinence | 16% | 32% | <0.05 |

| Time to first drink | 67 days | 81 days | <0.05 |

| Treatment retention | 24% | 46% | <0.05 |

| Clinical Global Impression | <0.05 | ||

| Marked or slight improvement | 11 | 25 | |

| No change | 11 | 13 | |

| Slightly or much worse | 28 | 12 |

. | No nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | Nurse follow-up (n = 50) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute abstinence | 16% | 32% | <0.05 |

| Time to first drink | 67 days | 81 days | <0.05 |

| Treatment retention | 24% | 46% | <0.05 |

| Clinical Global Impression | <0.05 | ||

| Marked or slight improvement | 11 | 25 | |

| No change | 11 | 13 | |

| Slightly or much worse | 28 | 12 |

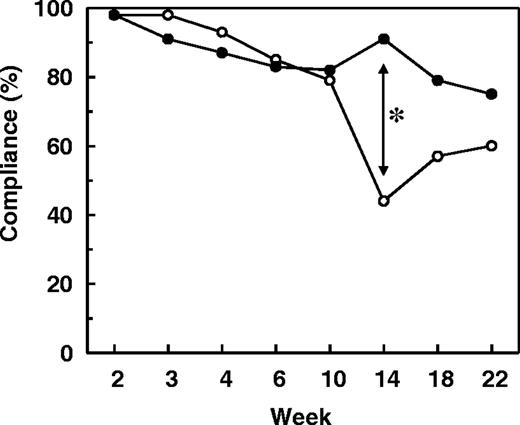

Compliance to medication was >75% throughout the study in those followed up by the nurse and higher than in those not followed up, particularly once the inpatient phase had ended at 3 weeks (Fig. 2). However, only the difference at week 14 was statistically significant.

Compliance to medication. Data are presented as the percentage compliance in patients with nurse follow-up (filled circles) and those without (open circles). The asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.021; analysis of variance with repeated measures).

Subgroup analysis of determinants of abstinence

During the first phase of identifying determinants of abstinence, the outcome (expressed as mean CADP) was compared between the treatment groups and in the different subgroups of patients using a two-way analysis of variance (Table 3). Differences in outcome were observed for most of the baseline demographic factors, but a statistically significant subgroup effect was found only for gender and educational status, with the outcome being better in males and in those who were better educated.

Cumulative abstinence duration proportion (CADP) by patient subgroups

| Variable . | Nurse follow-up . | No nurse follow-up . | Subgroup effect (P) . | Treatment interaction (P) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| <45 years | 0.53 (n = 28) | 0.30 (n = 25) | 0.08 | 0.33 | ||||

| >45 years | 0.58 (n = 22) | 0.49 (n = 25) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0.60 (n = 41) | 0.41 (n = 37) | 0.05 | 0.21 | ||||

| Female | 0.34 (n = 9) | 0.35 (n = 13) | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 0.62 (n = 8) | 0.65 (n = 10) | 0.31 | 0.20 | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.54 (n = 42) | 0.33 (n = 40) | ||||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| In work | 0.72 (n = 16) | 0.45 (n = 12) | 0.32 | 0.39 | ||||

| Sick leave | 0.35 (n = 5) | 0.52 (n = 9) | ||||||

| Disability | 0.37 (n = 3) | 0.19 (n = 6) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.53 (n = 24) | 0.37 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Retired | 0.29 (n = 2) | 0.34 (n = 2) | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||||

| Primary | 0.49 (n = 14) | 0.28 (n = 18) | 0.01 | 0.09 | ||||

| Secondary | 0.58 (n = 24) | 0.33 (n = 20) | ||||||

| University | 0.58 (n = 12) | 0.67 (n = 12) | ||||||

| Family history | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.55 (n = 34) | 0.30 (n = 29) | 0.14 | 0.40 | ||||

| No | 0.56 (n = 16) | 0.52 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Self-help group participation | ||||||||

| Attendees | 0.41 (n = 30) | 0.51 (n = 36) | 0.62 | 0.008 | ||||

| Non-attendees | 0.65 (n = 20) | 0.35 (n = 14) | ||||||

| Variable . | Nurse follow-up . | No nurse follow-up . | Subgroup effect (P) . | Treatment interaction (P) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| <45 years | 0.53 (n = 28) | 0.30 (n = 25) | 0.08 | 0.33 | ||||

| >45 years | 0.58 (n = 22) | 0.49 (n = 25) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0.60 (n = 41) | 0.41 (n = 37) | 0.05 | 0.21 | ||||

| Female | 0.34 (n = 9) | 0.35 (n = 13) | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 0.62 (n = 8) | 0.65 (n = 10) | 0.31 | 0.20 | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.54 (n = 42) | 0.33 (n = 40) | ||||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| In work | 0.72 (n = 16) | 0.45 (n = 12) | 0.32 | 0.39 | ||||

| Sick leave | 0.35 (n = 5) | 0.52 (n = 9) | ||||||

| Disability | 0.37 (n = 3) | 0.19 (n = 6) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.53 (n = 24) | 0.37 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Retired | 0.29 (n = 2) | 0.34 (n = 2) | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||||

| Primary | 0.49 (n = 14) | 0.28 (n = 18) | 0.01 | 0.09 | ||||

| Secondary | 0.58 (n = 24) | 0.33 (n = 20) | ||||||

| University | 0.58 (n = 12) | 0.67 (n = 12) | ||||||

| Family history | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.55 (n = 34) | 0.30 (n = 29) | 0.14 | 0.40 | ||||

| No | 0.56 (n = 16) | 0.52 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Self-help group participation | ||||||||

| Attendees | 0.41 (n = 30) | 0.51 (n = 36) | 0.62 | 0.008 | ||||

| Non-attendees | 0.65 (n = 20) | 0.35 (n = 14) | ||||||

Cumulative abstinence duration proportion (CADP) by patient subgroups

| Variable . | Nurse follow-up . | No nurse follow-up . | Subgroup effect (P) . | Treatment interaction (P) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| <45 years | 0.53 (n = 28) | 0.30 (n = 25) | 0.08 | 0.33 | ||||

| >45 years | 0.58 (n = 22) | 0.49 (n = 25) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0.60 (n = 41) | 0.41 (n = 37) | 0.05 | 0.21 | ||||

| Female | 0.34 (n = 9) | 0.35 (n = 13) | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 0.62 (n = 8) | 0.65 (n = 10) | 0.31 | 0.20 | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.54 (n = 42) | 0.33 (n = 40) | ||||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| In work | 0.72 (n = 16) | 0.45 (n = 12) | 0.32 | 0.39 | ||||

| Sick leave | 0.35 (n = 5) | 0.52 (n = 9) | ||||||

| Disability | 0.37 (n = 3) | 0.19 (n = 6) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.53 (n = 24) | 0.37 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Retired | 0.29 (n = 2) | 0.34 (n = 2) | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||||

| Primary | 0.49 (n = 14) | 0.28 (n = 18) | 0.01 | 0.09 | ||||

| Secondary | 0.58 (n = 24) | 0.33 (n = 20) | ||||||

| University | 0.58 (n = 12) | 0.67 (n = 12) | ||||||

| Family history | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.55 (n = 34) | 0.30 (n = 29) | 0.14 | 0.40 | ||||

| No | 0.56 (n = 16) | 0.52 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Self-help group participation | ||||||||

| Attendees | 0.41 (n = 30) | 0.51 (n = 36) | 0.62 | 0.008 | ||||

| Non-attendees | 0.65 (n = 20) | 0.35 (n = 14) | ||||||

| Variable . | Nurse follow-up . | No nurse follow-up . | Subgroup effect (P) . | Treatment interaction (P) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| <45 years | 0.53 (n = 28) | 0.30 (n = 25) | 0.08 | 0.33 | ||||

| >45 years | 0.58 (n = 22) | 0.49 (n = 25) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0.60 (n = 41) | 0.41 (n = 37) | 0.05 | 0.21 | ||||

| Female | 0.34 (n = 9) | 0.35 (n = 13) | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 0.62 (n = 8) | 0.65 (n = 10) | 0.31 | 0.20 | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.54 (n = 42) | 0.33 (n = 40) | ||||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| In work | 0.72 (n = 16) | 0.45 (n = 12) | 0.32 | 0.39 | ||||

| Sick leave | 0.35 (n = 5) | 0.52 (n = 9) | ||||||

| Disability | 0.37 (n = 3) | 0.19 (n = 6) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.53 (n = 24) | 0.37 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Retired | 0.29 (n = 2) | 0.34 (n = 2) | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||||

| Primary | 0.49 (n = 14) | 0.28 (n = 18) | 0.01 | 0.09 | ||||

| Secondary | 0.58 (n = 24) | 0.33 (n = 20) | ||||||

| University | 0.58 (n = 12) | 0.67 (n = 12) | ||||||

| Family history | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.55 (n = 34) | 0.30 (n = 29) | 0.14 | 0.40 | ||||

| No | 0.56 (n = 16) | 0.52 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Self-help group participation | ||||||||

| Attendees | 0.41 (n = 30) | 0.51 (n = 36) | 0.62 | 0.008 | ||||

| Non-attendees | 0.65 (n = 20) | 0.35 (n = 14) | ||||||

There was also an interaction between many of these demographic variables and treatment. However, the only variable for which there was a statistically significant interaction with the treatment arm in terms of outcome, was the participation in the self-help groups. It was observed that the patients who did not attend the self-help groups responded well to the nurse follow-up, whereas there was no benefit of the nurse follow-up in the patients who attended self-help groups.

A number of other evaluated variables had no evident effect on either the outcome or in the response to follow-up. These included the initial severity of alcohol dependence, drinking pattern, the number of previous detoxifications, smoking and domestic situation.

To provide a simultaneous analysis of the impact of these factors on the outcome, the existing predictors were entered into a stepwise multivariate regression analysis. Five variables influenced abstinence: follow-up, gender, marital status, education level and participation in the self-help groups. Of these factors, nurse follow-up was found to be the most important determinant of CADP, adding 0.290 to the CADP. However, the size of the main effect of follow-up is limited by two variables, which interact significantly with follow-up, namely, gender and participation in the self-help groups: in female patients and the participants in the self-help groups, the gain in CADP observed overall was considerably attenuated (by 0.245 and 0.226, respectively). Taken together, the first three effects show that the nurse follow-up is generally beneficial for all the subgroups, although male patients and patients not attending the self-help groups benefit the most. Finally, two variables were shown to influence CAD independently, with no interaction with the follow-up treatment group; these were marital status (0.172 increase in CADP for married subjects compared with unmarried subjects) and education (0.119 increase in CADP for each additional educational level). No other variable was shown to have a significant effect on the abstinence outcome.

Safety

A total of 280 adverse events in 83 patients were reported during the study. The most frequently reported were psychiatric conditions, such as depression and insomnia (in 50 patients), and gastrointestinal events, notably nausea and diarrhoea (in 47 patients). Nevertheless, the intensity of 27 psychiatric and 19 gastrointestinal events was moderate or mild and 33 (66%) and 24 (51%) patients, respectively, required no treatment. Thirty-one serious adverse events were reported in 26 patients, including hospitalizations due to drinking (in 12 patients); none of these was considered by the investigator to be related to the study medication.

DISCUSSION

Efficacy of nurse follow-up

This study demonstrated a significant difference in retention in the trial and in the degree of abstinence, measured as the cumulative abstinence duration, achieved by the recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients, according to whether they had received a follow-up from the nurse. The principal effect of the intervention is likely to be a reduction in the probability of dropout due to the frequent contact by the nurse. The effect on abstinence ratings may, however, be an artefact of the improved retention, since dropouts are considered as de facto non-abstinent. Any large difference in dropout rate between the treatment arms will thus influence the effect size on abstinence. Given that 76% of patients in the no nurse follow-up group dropped out, this could make an important contribution to the observed difference in abstinence. Nonetheless, retention in treatment programmes is known to be an important determinant of abstinence (Hu et al., 1997), so the inter-group difference in abstinence rates is unlikely to be entirely an artefact.

Comparison with previous studies with acamprosate

The superior outcome in the patients receiving the nurse follow-up was also observed with the secondary drinking-related outcome measures. In addition, these patients had a better compliance with the medication. The finding of a better compliance is important, since it suggests a synergistic, rather than a simply additive interaction between psychosocial intervention and pharmacotherapy. This observation is complementary to that made in a number of randomized clinical trials, with acamprosate showing a superior adherence to psychosocial support programmes in patients taking acamprosate (Pelc et al., 1992; Paille et al., 1995; Geerlings et al., 1997).

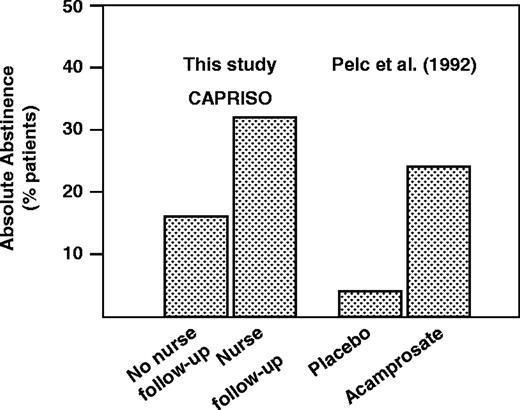

The outcome rates obtained in this open study can be compared with the previous data obtained with acamprosate in a very similar patient population, using a comparable treatment protocol at the same clinic (Pelc et al., 1992). The overall rate of absolute abstinence in this study (both treatment groups combined) was the same as that obtained with the acamprosate treatment group in the clinical trial (24%), where psychosocial support was not formalized. However, when the rates of absolute abstinence seen in the present study are compared with those in the clinical trial, the level of success obtained without the follow-up is not as high as in the acamprosate arm of the trial, whereas in the patients with the nurse follow-up, the abstinence rates observed are considerably higher (Fig. 3). These findings illustrate how the treatment benefit of acamprosate can be improved by an appropriate psychosocial support.

Absolute abstinence rates after 6 months of treatment in this study (CAPRISO) and in the Belgium randomized placebo-controlled trial of acamprosate of Pelc et al. (1992).

Moreover, the observation that the intensity of follow-up in patients treated with acamprosate influences the abstinence outcome may help explain why different absolute rates of abstinence have been reported in the various clinical trials performed with acamprosate, in each of which, the extent and nature of psychosocial support differed (Mason, 2001). It is important to note that the absence of psychosocial support in our no follow-up treatment group did not abolish the effect of acamprosate; abstinence rates being still significantly higher than those observed in the placebo arm of the clinical trial.

Determinants of outcome

An attempt was made to determine the impact of psychosocial follow-up according to various sociodemographic variables that are known to be important in determining success in the rehabilitation programmes for alcohol-dependent patients. Although the results should be interpreted cautiously on account of the relatively low number of patients, significant treatment interactions were observed between gender and participation in self-help groups. It is interesting to consider why these two factors should influence the utility of psychosocial follow-up. In the case of self-help group participation, it is possible that the nurse's follow-up fulfilled a similar supportive function for the patient, as did participation in the self-help groups. Either function could thus optimize the outcome, while the use of both provided no further benefit. In the case of gender, the findings are more difficult to explain. It is possible that the apparent gender difference may, in fact, reveal other determinants of abstinence that are unequally distributed between genders. For example, the proportion of males living alone was higher than that of females. Family support is known to improve the outcome (Booth et al., 1992), and it may be that this may have substituted for the active nurse intervention in females, whereas in males, a contact with the community nurse was the only social support the male patients received. Alternatively, the incidence of explicit anxio-depressive symptomatology was higher in females than in males, and this may have rendered them less responsive to the kind of psychosocial support used in this study. Comorbid anxiety and depression have been reported previously to decrease the probability of achieving a stable abstinence (Marshall and Alam, 1997; Pelc et al., 2002) Whatever the reason, this analysis suggests that there may indeed be subgroups of patients who respond better than others to psychosocial support. These factors need to be clearly identified in future studies so that the type of psychosocial support provided to individual patients can be optimized according to their particular needs and situation.

In conclusion, this study appeared to show the added benefit of community nurse follow-up on treatment retention and in achieving abstinence in recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients treated with acamprosate.

The study was supported by Merck SA. F. L. is a scientific advisor to, and an employee of, Merck SA. P. L. is an independent expert on statistical issues.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association (

Ansoms, C., Deckers, F., Lehert, P. et al. (

Baekeland, F. and Lundwall, L. (

Balldin, J., Berglund, M., Borg, S. et al. (

Booth, R. M., Russell, D. W., Soucek, S. and Laughlin, P. R. (

De Wildt, W. A., Schippers, G. M., Van Den Brink, W. et al. (

Garbutt, J. C., West, S. L., Carey, T. S. et al. (

Geerlings, P. J., Ansoms, C. and Van der Brink, W. (

Gilbert, F. S. (

Hammarberg, A., Wennberg, P., Beck, O. et al. (

Heinälä, P., Alho, H., Kiianmaa, K. et al. (

Hu, T., Hunnkeler, E. M., Weisner, C. et al. (

Marshall, E. J. and Alam, F. (

Mason, B. J. (

Mattson, M. E., Del Boca, F. K., Carroll, K. M. et al. (

Miller, W. R. and Wilbourne, P. L. (

O'Malley, S. S., Jaffe, A. J., Chang, G. et al. (

Paille, F. M., Guelfi, J. D., Perkins, A. C. et al. (

Pelc, I., Le Bon, O., Verbanck, P. et al. (

Pelc, I., Ansoms, C., Lehert, P. et al. (

Soyka, M. A., Preuss, U. and Schuetz, C. (

Author notes

1Psychiatry Department, Hôpital Universitaire Brugmann, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Place A. van Gehuchten 4, 1020 Bruxelles, Belgium

2The Faculty of Medicine, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia and Department of Statistics, FUCAM, Mons, Belgium

3Merck SA, 37, rue St Romain, 69379 Lyon Cedex 08, France