-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joseph F Naimoli, Sweta Saxena, Laurel E Hatt, Kristina M Yarrow, Trenton M White, Temitayo Ifafore-Calfee, Health system strengthening: prospects and threats for its sustainability on the global health policy agenda, Health Policy and Planning, Volume 33, Issue 1, January 2018, Pages 85–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx147

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In 2013, Hafner and Shiffman applied Kingdon’s public policy process model to explain the emergence of global attention to health system strengthening (HSS). They questioned, however, HSS’s sustainability on the global health policy agenda, citing various concerns. Guided by the Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation, we advance and elaborate a proposition: a confluence of developments will contribute to maintaining HSS’s prominent place on the agenda until at least 2030. Those developments include (1) technical, managerial, financial, and political responses to unpredictable public health crises that imperil the routine functioning of health systems, such as the 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease (Ebola) epidemic in West Africa; (2) similar responses to non-crisis situations requiring fully engaged, robust health systems, such as the pursuit of the new Sustainable Development Goal for health (SDG3); and (3) increased availability of new knowledge about system change at macro, meso, and micro levels and its effects on people’s health and well-being. To gauge the accuracy of our proposition, we carried out a speculative assessment of credible threats to our premise by discussing all of the Hafner-Shiffman concerns. We conclude that (1) the components of our proposition and other forces that have the potential to promote continuing attention to HSS are of sufficient strength to counteract these concerns, and (2) prospective monitoring of HSS agenda status and further research on agenda sustainability can increase confidence in our threat assessment.

Key Messages

The policy literature on agenda-setting is extensive; the literature on agenda sustainability is far less so. This paper addresses this deficit.

We posit that health system strengthening (HSS) will maintain a prominent place on the global health policy agenda until at least 2030 because of a confluence of developments.

Those developments include (1) technical, managerial, financial, and political responses to unpredictable public health crises that imperil the routine functioning of health systems; (2) similar responses to non-crisis situations requiring fully engaged, robust health systems; and (3) increased availability of new knowledge about system change at macro, meso, and micro levels and its effects on people’s health and well-being.

Recent credible speculations about HSS agenda sustainability can work against our proposition.

Our risk assessment argues that the three components of our proposition, combined with other forces that have the potential to promote HSS agenda sustainability, are of sufficient strength to counteract current or potential threats.

We recognize that prospective monitoring of HSS agenda status and further research on HSS agenda sustainability could increase confidence in our assessment.

Introduction

In 2013, Hafner and Shiffman applied Kingdon’s public policy process model to explain the emergence of global attention to health system strengthening (HSS) (Hafner and Shiffman 2013). The authors questioned, however, HSS’s sustainability on the global health policy agenda, citing various concerns. Drawing on the Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation (Grindle and Thomas 1991) (henceforth the G&T model) and emerging evidence about the dynamics of health system change, we advance and elaborate a proposition: a confluence of developments will contribute to maintaining HSS’s prominent place on the agenda until at least 2030. To gauge the accuracy of our proposition, we carried out a speculative assessment of the Hafner-Shiffman concerns, which we consider to be credible threats to our proposition. We conclude that (1) the components of our proposition, combined with other forces that have the potential to promote HSS agenda sustainability, are of sufficient strength to counteract those concerns, and (2) prospective monitoring of HSS agenda status and further research can increase confidence in our threat assessment. The policy literature on agenda-setting is extensive (Baumgartner 2016; Green-Pedersen and Walgrave 2014); the literature on agenda sustainability is far less so. This paper helps address this deficit.

Methods

Definitions

Health systems strengthening

A consensus on an operational definition of HSS remains elusive (Reich and Takemi 2009); consequently, we have adopted a broad and inclusive formulation that reflects WHO’s definition and accommodates multiple perspectives in use. WHO defines HSS as ‘any array of initiatives and strategies that improves one or more of the functions of the health system and that leads to better health through improvements in access, coverage, quality, or efficiency’ (World Health Organization 2014a). The instrumental or extrinsic perspective views system strengthening as an intentional or unintentional consequence of improvements in the performance of categorical health programs and the achievement of their short-term objectives. The intrinsic perspective views HSS as a range of interdependent, purposeful strategies and approaches that address the root causes of sub-optimal health system performance (e.g. inadequate governance, weak or missing policies and regulations, insufficient financing, and poor organization of health service delivery) that limit the ability of the health system as a whole to achieve sustainable, equitable, health-promoting outcomes at scale for all people (Chee et al. 2013; Travis et al. 2004; World Health Organization 2007).

Agenda sustainability

According to Kingdon, a policy agenda is ‘the list of subjects or problems to which government officials, and people outside of government closely associated with those officials, are paying some serious attention at any given time’ (Kingdon 1995). Agenda setting comprises a series of decision-making processes that result in an issue or problem (chosen from a range of specified alternatives) rising to a level of prominence on the policy agenda (Kingdon 1995). Agenda sustainability is a consequence of the implementation of the policy decision, particularly the ability of the issue or problem to maintain its agenda prominence over time in response to various challenges that promote or inhibit implementation (Grindle and Thomas 1991).

Conceptual framework

Our proposition about HSS agenda sustainability is grounded in the G&T model (Table 1) (Grindle and Thomas 1991), which emerged from their analysis of a range of policy reform cases across multiple sectors in numerous developing countries under varying political regimes over many decades. Although the model is based on observations of actors and processes at country level, we believe it can be applied to actors and processes that influence HSS sustainability at the global level. The first stage in the model—agenda setting—was the subject of the Hafner-Shiffman well-known publication on HSS. Applying Kingdon’s policy model (Kingdon 1995), they identified the factors, pressures, and sources that they believed led to the emergence of global attention to HSS (Table 2).

The Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation

| The Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation4 conceives of policy reform as a dynamic process: different actors exert pressure for or against a policy, at different points along the pathway to reform. Different reactions to policy change initiatives, such as promoting, revising, or reversing a policy, influence which of multiple potential outcomes will emerge. Understanding which policy outcome will emerge requires knowledge of the location, strength, and stakes involved in each reaction. The model comprises different stages: placing reforms on the policy agenda, authorization, implementation, and sustainability. |

| The agenda-setting phase is characterized by pressures from many sources to place a particular reform on the policy agenda, some of which are acted upon, some of which are acted upon but not implemented, and many of which are never acted upon. |

| The authorization or decision process for a specific agenda issue involves a series of both formal and informal stages, often engaging both the bureaucracy and higher orders of political decision-making. Decisions are reversible: they can be overturned at higher levels or revised, often as a function of implementation experience when the implications of the policy gradually become more visible. |

| Implementation of the initiative as intended is influenced by its characteristics (e.g., distribution of costs and benefits, technical complexity, administrative intensity, timing of impact), which determine not only the arena in which the reaction to the initiative will occur (public or bureaucratic), but also the resources required for successful implementation. |

| To sustain a reform, decision makers and policy managers must mobilize political, financial, managerial, and technical resources. As with other stages in the policy process, obtaining the necessary resources for sustainability is a contested undertaking. |

| The Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation4 conceives of policy reform as a dynamic process: different actors exert pressure for or against a policy, at different points along the pathway to reform. Different reactions to policy change initiatives, such as promoting, revising, or reversing a policy, influence which of multiple potential outcomes will emerge. Understanding which policy outcome will emerge requires knowledge of the location, strength, and stakes involved in each reaction. The model comprises different stages: placing reforms on the policy agenda, authorization, implementation, and sustainability. |

| The agenda-setting phase is characterized by pressures from many sources to place a particular reform on the policy agenda, some of which are acted upon, some of which are acted upon but not implemented, and many of which are never acted upon. |

| The authorization or decision process for a specific agenda issue involves a series of both formal and informal stages, often engaging both the bureaucracy and higher orders of political decision-making. Decisions are reversible: they can be overturned at higher levels or revised, often as a function of implementation experience when the implications of the policy gradually become more visible. |

| Implementation of the initiative as intended is influenced by its characteristics (e.g., distribution of costs and benefits, technical complexity, administrative intensity, timing of impact), which determine not only the arena in which the reaction to the initiative will occur (public or bureaucratic), but also the resources required for successful implementation. |

| To sustain a reform, decision makers and policy managers must mobilize political, financial, managerial, and technical resources. As with other stages in the policy process, obtaining the necessary resources for sustainability is a contested undertaking. |

The Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation

| The Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation4 conceives of policy reform as a dynamic process: different actors exert pressure for or against a policy, at different points along the pathway to reform. Different reactions to policy change initiatives, such as promoting, revising, or reversing a policy, influence which of multiple potential outcomes will emerge. Understanding which policy outcome will emerge requires knowledge of the location, strength, and stakes involved in each reaction. The model comprises different stages: placing reforms on the policy agenda, authorization, implementation, and sustainability. |

| The agenda-setting phase is characterized by pressures from many sources to place a particular reform on the policy agenda, some of which are acted upon, some of which are acted upon but not implemented, and many of which are never acted upon. |

| The authorization or decision process for a specific agenda issue involves a series of both formal and informal stages, often engaging both the bureaucracy and higher orders of political decision-making. Decisions are reversible: they can be overturned at higher levels or revised, often as a function of implementation experience when the implications of the policy gradually become more visible. |

| Implementation of the initiative as intended is influenced by its characteristics (e.g., distribution of costs and benefits, technical complexity, administrative intensity, timing of impact), which determine not only the arena in which the reaction to the initiative will occur (public or bureaucratic), but also the resources required for successful implementation. |

| To sustain a reform, decision makers and policy managers must mobilize political, financial, managerial, and technical resources. As with other stages in the policy process, obtaining the necessary resources for sustainability is a contested undertaking. |

| The Grindle and Thomas interactive model of policy implementation4 conceives of policy reform as a dynamic process: different actors exert pressure for or against a policy, at different points along the pathway to reform. Different reactions to policy change initiatives, such as promoting, revising, or reversing a policy, influence which of multiple potential outcomes will emerge. Understanding which policy outcome will emerge requires knowledge of the location, strength, and stakes involved in each reaction. The model comprises different stages: placing reforms on the policy agenda, authorization, implementation, and sustainability. |

| The agenda-setting phase is characterized by pressures from many sources to place a particular reform on the policy agenda, some of which are acted upon, some of which are acted upon but not implemented, and many of which are never acted upon. |

| The authorization or decision process for a specific agenda issue involves a series of both formal and informal stages, often engaging both the bureaucracy and higher orders of political decision-making. Decisions are reversible: they can be overturned at higher levels or revised, often as a function of implementation experience when the implications of the policy gradually become more visible. |

| Implementation of the initiative as intended is influenced by its characteristics (e.g., distribution of costs and benefits, technical complexity, administrative intensity, timing of impact), which determine not only the arena in which the reaction to the initiative will occur (public or bureaucratic), but also the resources required for successful implementation. |

| To sustain a reform, decision makers and policy managers must mobilize political, financial, managerial, and technical resources. As with other stages in the policy process, obtaining the necessary resources for sustainability is a contested undertaking. |

Emergence of global attention to health system strengthening: Hafner’s and Shiffman’s application of Kingdon’s public policy process model

| In his model of policy formulation, Kingdon recognizes the important roles of both actors and processes, and distinguishes between them. Regarding the latter, he conceives of three process streams—each of which is largely independent of the others and develops in accordance with its own rules and dynamics—that flow through any system. They are problems, policies, and politics.5 |

| According to Kingdon, ‘…at some critical junctures, the three streams are joined, and the greatest policy changes grow out of that coupling of problems, policy proposals, and politics…solutions become joined to problems, and both of them are joined to favourable political forces. The coupling is most likely when policy windows—opportunities for pushing pet proposals or conceptions of problems—are open.’ |

| Hafner and Shiffman6 adopted and adapted Kingdon’s model to explain the emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. The factors they cited included emerging evidence of a health workforce crisis and problematic relationships between global health initiatives (GHIs) and health systems (problem stream); a legacy of attention to horizontal strategies for strengthening health sectors7,8 and the emergence and influence of a health systems research policy community (policy stream); and, slow progress and pressure to achieve the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), combined with donor moves toward aid coordination (politics stream). |

| In his model of policy formulation, Kingdon recognizes the important roles of both actors and processes, and distinguishes between them. Regarding the latter, he conceives of three process streams—each of which is largely independent of the others and develops in accordance with its own rules and dynamics—that flow through any system. They are problems, policies, and politics.5 |

| According to Kingdon, ‘…at some critical junctures, the three streams are joined, and the greatest policy changes grow out of that coupling of problems, policy proposals, and politics…solutions become joined to problems, and both of them are joined to favourable political forces. The coupling is most likely when policy windows—opportunities for pushing pet proposals or conceptions of problems—are open.’ |

| Hafner and Shiffman6 adopted and adapted Kingdon’s model to explain the emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. The factors they cited included emerging evidence of a health workforce crisis and problematic relationships between global health initiatives (GHIs) and health systems (problem stream); a legacy of attention to horizontal strategies for strengthening health sectors7,8 and the emergence and influence of a health systems research policy community (policy stream); and, slow progress and pressure to achieve the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), combined with donor moves toward aid coordination (politics stream). |

Emergence of global attention to health system strengthening: Hafner’s and Shiffman’s application of Kingdon’s public policy process model

| In his model of policy formulation, Kingdon recognizes the important roles of both actors and processes, and distinguishes between them. Regarding the latter, he conceives of three process streams—each of which is largely independent of the others and develops in accordance with its own rules and dynamics—that flow through any system. They are problems, policies, and politics.5 |

| According to Kingdon, ‘…at some critical junctures, the three streams are joined, and the greatest policy changes grow out of that coupling of problems, policy proposals, and politics…solutions become joined to problems, and both of them are joined to favourable political forces. The coupling is most likely when policy windows—opportunities for pushing pet proposals or conceptions of problems—are open.’ |

| Hafner and Shiffman6 adopted and adapted Kingdon’s model to explain the emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. The factors they cited included emerging evidence of a health workforce crisis and problematic relationships between global health initiatives (GHIs) and health systems (problem stream); a legacy of attention to horizontal strategies for strengthening health sectors7,8 and the emergence and influence of a health systems research policy community (policy stream); and, slow progress and pressure to achieve the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), combined with donor moves toward aid coordination (politics stream). |

| In his model of policy formulation, Kingdon recognizes the important roles of both actors and processes, and distinguishes between them. Regarding the latter, he conceives of three process streams—each of which is largely independent of the others and develops in accordance with its own rules and dynamics—that flow through any system. They are problems, policies, and politics.5 |

| According to Kingdon, ‘…at some critical junctures, the three streams are joined, and the greatest policy changes grow out of that coupling of problems, policy proposals, and politics…solutions become joined to problems, and both of them are joined to favourable political forces. The coupling is most likely when policy windows—opportunities for pushing pet proposals or conceptions of problems—are open.’ |

| Hafner and Shiffman6 adopted and adapted Kingdon’s model to explain the emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. The factors they cited included emerging evidence of a health workforce crisis and problematic relationships between global health initiatives (GHIs) and health systems (problem stream); a legacy of attention to horizontal strategies for strengthening health sectors7,8 and the emergence and influence of a health systems research policy community (policy stream); and, slow progress and pressure to achieve the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), combined with donor moves toward aid coordination (politics stream). |

Once on the agenda, a reform faces a series of authorization and implementation challenges—the second and third stages in the G&T model. Decisions are reversible: they can be altered by implementation experience. Determining reform feasibility and implementation success require anticipating in which arena (public or bureaucratic) the reform will occur, identifying those who support and oppose it, and undertaking strategic actions informed by this knowledge. A burgeoning literature on implementation research in health in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) promises to provide new insights on the relationship between implementation and policy formulation and reformulation (Peters et al. 2013).

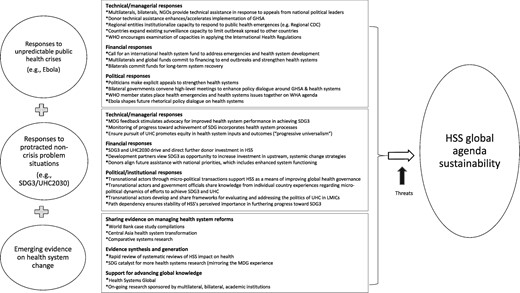

The focus of this paper is sustainability, the fourth stage in the G&T model. During the implementation process, the authors identify four kinds of resources that decision makers and policy managers must mobilize to sustain any reform: technical, managerial, financial, and political. Resource mobilization occurs in both situations of crisis (which play out in the public arena) and non-crisis (which play out in the bureaucratic arena). Policy makers’ perception of whether a situation is a crisis or a non-crisis is fundamental: it affects the pressures for change, the stakes for reform, the identity of the decision makers, and the type and timing of change.

Proposition

We posit that a confluence of the following developments will contribute to maintaining HSS’s prominent place on the global agenda until at least 2030.

Local, regional, and global responses to unpredictable public health crises

Local, regional, and global responses to protracted non-crisis situations

Increasing availability of emerging evidence on health system change.

We have chosen 2030 for three reasons.

Any number of new or re-emergent public health crises can occur in the next 13 years, as demonstrated recently by the re-occurrence of Ebola virus disease (Ebola) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (World Health Organization 2017a) and local transmission of Zika virus infection throughout much of South and Central America and the Caribbean (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017).

Policy experts have set 2030 as the deadline for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal for health (SDG3) and its principal target, Universal Health Coverage (UHC). The successful attainment of the goal and target will rely upon robustly functioning health systems (Ahoobim et al. 2012).

We anticipate new evidence on health system change and its effects on health and other outcomes will become increasingly available between now and 2030 (WHO and Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research 2017).

Proposition application

We apply our proposition by examining responses to one recent crisis—the failure of health systems in West Africa to respond adequately to the Ebola outbreak—and one persistent, non-crisis situation—the latest global effort to address the longstanding challenge of achieving health for all, affordably, with equity—SDG3 and its accompanying UHC target. Finally, based on our collective judgment, we offer a purposeful selection of salient emerging research that can help policy makers and practitioners better understand the complex dynamics (technical, managerial, financial, and political) of health system change.

Proposition assessment

To assess adequately the accuracy of our proposition, we would need data from prospective monitoring and analysis of HSS agenda status at intervals between now and 2030, and/or a retrospective assessment closer to 2030. In the absence of these data at this time, we propose a speculative assessment. We view the Hafner-Shiffman concerns about HSS sustainability as credible threats that could potentially work against our proposition. In the discussion section, we address, in ascending order of threat level (in our judgment), their four concerns:

a weak evidence base (low);

pendulum swings in global health (low-moderate);

effects of the global financial crisis on HSS (moderate); and

preoccupations about some organizations’ embrace of HSS for its instrumental value (high).

Results

Unpredictable public health crises: the case of Ebola

We believe the attributes of the 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic in West Africa are consistent with the G&T characterization of a crisis (Table 3). Ebola, and the prospect of future public health emergencies, are likely to keep global attention focused on HSS. We postulate that the nature of the crisis in West Africa and the resources mobilized in response, have had and will continue to have important policy implications not only for HSS, but also for the pursuit of enhanced global health security (GHS) and greater health system resiliency. As Kutzin and Sparkes recently observed, HSS is not an end unto itself, but rather a vital means for achieving these and other ends (Kutzin and Sparkes 2016).

Characterization of a crisis (Grindle and Thomas) and its application to the case of Ebola

| Crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| A crisis encompasses a range of macropolitical events (such as macroeconomic, customs, or financial system reforms affecting multiple sectors) that are perceived by upper-level decision makers as having high political and economic stakes. The stakes are high because they threaten the power, prestige, legitimacy, and duration of national governing elites or interest groups; and/or social stability; and/or costs and benefits to major national interests. In a crisis situation, the pressure for reform is acute, often originating with small groups of governing elites and often influenced by interests outside of government. A crisis demands urgent action; the societal, political, and economic stakes of inaction are high. A crisis often precipitates major changes from existing policy.9 |

| Case: Ebola |

| During the 2014–2015 Ebola crisis in West Africa, more than 11, 000 people died in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.10 Adverse health outcomes, combined with the social, economic, and political upheaval Ebola provoked, resulted in a full-scale crisis in West Africa that affected all sectors. |

| For example, in Liberia, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf closed all beaches, imposed a quarantine and curfew in a Monrovia slum, suspended traditional burial practices, and imposed mandatory cremation, all of which contributed to social unrest.11–13 Schools closed between September 2014 and February 2015, impacting child education and household productivity.14 Arwady and colleagues reported that as early as 2014 the economy had already contracted, with a rise in the prices of commodities and certain foods.15 One survey of 337 Liberian businesses found 12% closed nationwide and 20% closed in Monrovia. Across Liberia, 24% of employees lost their jobs.16 The IMF estimated that Liberia’s real GDP growth dropped from 8.9% in 2013 to 0.7% in 2014.17 The government banned election rallies and postponed senatorial elections from October 2014 to December 2014.18,19 When elections were held, President Sirleaf’s governing party lost its majority in the Senate.20 |

| Ebola exacerbated the Liberian population’s already fragile confidence in its health system.21 Fear and distrust of government authorities and outsiders subjected some health workers and expatriate responders to physical violence and threats.22 There is suggestive evidence that the population reduced its use of basic health services; for example, monthly childhood vaccination rates dropped 60% by the end of 2014.23 The reduced availability of services and health workers, among other factors, lessened communities’ trust in their system.24 |

| Crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| A crisis encompasses a range of macropolitical events (such as macroeconomic, customs, or financial system reforms affecting multiple sectors) that are perceived by upper-level decision makers as having high political and economic stakes. The stakes are high because they threaten the power, prestige, legitimacy, and duration of national governing elites or interest groups; and/or social stability; and/or costs and benefits to major national interests. In a crisis situation, the pressure for reform is acute, often originating with small groups of governing elites and often influenced by interests outside of government. A crisis demands urgent action; the societal, political, and economic stakes of inaction are high. A crisis often precipitates major changes from existing policy.9 |

| Case: Ebola |

| During the 2014–2015 Ebola crisis in West Africa, more than 11, 000 people died in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.10 Adverse health outcomes, combined with the social, economic, and political upheaval Ebola provoked, resulted in a full-scale crisis in West Africa that affected all sectors. |

| For example, in Liberia, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf closed all beaches, imposed a quarantine and curfew in a Monrovia slum, suspended traditional burial practices, and imposed mandatory cremation, all of which contributed to social unrest.11–13 Schools closed between September 2014 and February 2015, impacting child education and household productivity.14 Arwady and colleagues reported that as early as 2014 the economy had already contracted, with a rise in the prices of commodities and certain foods.15 One survey of 337 Liberian businesses found 12% closed nationwide and 20% closed in Monrovia. Across Liberia, 24% of employees lost their jobs.16 The IMF estimated that Liberia’s real GDP growth dropped from 8.9% in 2013 to 0.7% in 2014.17 The government banned election rallies and postponed senatorial elections from October 2014 to December 2014.18,19 When elections were held, President Sirleaf’s governing party lost its majority in the Senate.20 |

| Ebola exacerbated the Liberian population’s already fragile confidence in its health system.21 Fear and distrust of government authorities and outsiders subjected some health workers and expatriate responders to physical violence and threats.22 There is suggestive evidence that the population reduced its use of basic health services; for example, monthly childhood vaccination rates dropped 60% by the end of 2014.23 The reduced availability of services and health workers, among other factors, lessened communities’ trust in their system.24 |

Characterization of a crisis (Grindle and Thomas) and its application to the case of Ebola

| Crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| A crisis encompasses a range of macropolitical events (such as macroeconomic, customs, or financial system reforms affecting multiple sectors) that are perceived by upper-level decision makers as having high political and economic stakes. The stakes are high because they threaten the power, prestige, legitimacy, and duration of national governing elites or interest groups; and/or social stability; and/or costs and benefits to major national interests. In a crisis situation, the pressure for reform is acute, often originating with small groups of governing elites and often influenced by interests outside of government. A crisis demands urgent action; the societal, political, and economic stakes of inaction are high. A crisis often precipitates major changes from existing policy.9 |

| Case: Ebola |

| During the 2014–2015 Ebola crisis in West Africa, more than 11, 000 people died in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.10 Adverse health outcomes, combined with the social, economic, and political upheaval Ebola provoked, resulted in a full-scale crisis in West Africa that affected all sectors. |

| For example, in Liberia, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf closed all beaches, imposed a quarantine and curfew in a Monrovia slum, suspended traditional burial practices, and imposed mandatory cremation, all of which contributed to social unrest.11–13 Schools closed between September 2014 and February 2015, impacting child education and household productivity.14 Arwady and colleagues reported that as early as 2014 the economy had already contracted, with a rise in the prices of commodities and certain foods.15 One survey of 337 Liberian businesses found 12% closed nationwide and 20% closed in Monrovia. Across Liberia, 24% of employees lost their jobs.16 The IMF estimated that Liberia’s real GDP growth dropped from 8.9% in 2013 to 0.7% in 2014.17 The government banned election rallies and postponed senatorial elections from October 2014 to December 2014.18,19 When elections were held, President Sirleaf’s governing party lost its majority in the Senate.20 |

| Ebola exacerbated the Liberian population’s already fragile confidence in its health system.21 Fear and distrust of government authorities and outsiders subjected some health workers and expatriate responders to physical violence and threats.22 There is suggestive evidence that the population reduced its use of basic health services; for example, monthly childhood vaccination rates dropped 60% by the end of 2014.23 The reduced availability of services and health workers, among other factors, lessened communities’ trust in their system.24 |

| Crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| A crisis encompasses a range of macropolitical events (such as macroeconomic, customs, or financial system reforms affecting multiple sectors) that are perceived by upper-level decision makers as having high political and economic stakes. The stakes are high because they threaten the power, prestige, legitimacy, and duration of national governing elites or interest groups; and/or social stability; and/or costs and benefits to major national interests. In a crisis situation, the pressure for reform is acute, often originating with small groups of governing elites and often influenced by interests outside of government. A crisis demands urgent action; the societal, political, and economic stakes of inaction are high. A crisis often precipitates major changes from existing policy.9 |

| Case: Ebola |

| During the 2014–2015 Ebola crisis in West Africa, more than 11, 000 people died in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.10 Adverse health outcomes, combined with the social, economic, and political upheaval Ebola provoked, resulted in a full-scale crisis in West Africa that affected all sectors. |

| For example, in Liberia, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf closed all beaches, imposed a quarantine and curfew in a Monrovia slum, suspended traditional burial practices, and imposed mandatory cremation, all of which contributed to social unrest.11–13 Schools closed between September 2014 and February 2015, impacting child education and household productivity.14 Arwady and colleagues reported that as early as 2014 the economy had already contracted, with a rise in the prices of commodities and certain foods.15 One survey of 337 Liberian businesses found 12% closed nationwide and 20% closed in Monrovia. Across Liberia, 24% of employees lost their jobs.16 The IMF estimated that Liberia’s real GDP growth dropped from 8.9% in 2013 to 0.7% in 2014.17 The government banned election rallies and postponed senatorial elections from October 2014 to December 2014.18,19 When elections were held, President Sirleaf’s governing party lost its majority in the Senate.20 |

| Ebola exacerbated the Liberian population’s already fragile confidence in its health system.21 Fear and distrust of government authorities and outsiders subjected some health workers and expatriate responders to physical violence and threats.22 There is suggestive evidence that the population reduced its use of basic health services; for example, monthly childhood vaccination rates dropped 60% by the end of 2014.23 The reduced availability of services and health workers, among other factors, lessened communities’ trust in their system.24 |

Technical/managerial response

Although the Ebola crisis was limited to three West African countries, the message it conveyed about the urgent need to attend to weak health systems reverberated regionally and globally.

Regional response

Health systems were particularly ill-prepared in four critical areas: surveillance (McNamara et al. 2016), infection prevention and control (Hageman et al. 2016), health workforce readiness (Greenemeier 2014), and community outreach (Bedrosian et al. 2016). The outbreak demonstrated the need for a coordinated response to these kinds of system deficiencies, particularly with regard to surveillance. Countries with shared borders relied on one another for data and cross-border reconnaissance (Moon et al. 2015). When it became known that a traveller with Ebola arriving in Lagos from Monrovia had unprotected contact with multiple Ebola responders, the Nigerian government rapidly activated its existing national polio surveillance system, which helped restrict the outbreak to 19 cases and limit its spread to the rest of Nigeria, Africa, and beyond (Bell et al. 2016; Liu 2016). In January 2017, the African Union launched the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (African CDC) to help member states improve surveillance (via functional and linked laboratory networks in the five African sub-regions) and their overall response to public health emergencies (Nkengasong et al. 2017). The WHO Regional Office for Africa’s 2016–2020 strategy seeks to establish a regional health workforce to promptly respond to future emergencies (Regional Office for Africa 2016).

Global response

With the exception of Medecins Sans Frontiers, which repeatedly alerted the global community to the seriousness of the outbreak, helped draft the first case management protocols, and instructed others how to treat patients (Hayden 2015), the response was delayed (Moon et al. 2015; Siedner and Kraemer 2014), but ultimately robust. Multilateral (e.g. WHO, the World Bank, UN Agencies, African Development Bank), bilateral (e.g. the U.S. and the U.K.), and over 60 non-governmental organizations (Light 2014) provided direct or indirect technical and management support to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. Four global commissions that emerged in Ebola’s aftermath consistently recommended strengthening national health systems as part of a broad agenda for improving global health preparedness and response for future infectious disease threats (Gostin et al. 2016). Ebola also triggered a reconsideration of countries’ capacity to comply with the International Health Regulations (IHR), which represent the core functions of a public health system, and the role the international community plays in enhancing such capacities (World Health Organization 2016 b). Recent reviews of the status of countries’ implementation of the IHR indicate significant room for improvement (Gostin et al. 2015; Moon et al. 2015) and WHO has developed guidelines to help governments determine whether they are meeting core capacity requirements (Gostin et al. 2015; WHO Director-General 2015; World Health Organization 2016a). The Health Data Collaborative, a partnership of international agencies, governments, philanthropies, donors, and academics committed to improving health data, is developing standards for integrating outbreak surveillance data into routine health information systems (World Health Organization 2015).

Financial response

The crisis stimulated global dialogue and action about future technical cooperation and financial assistance for HSS, particularly in fragile states. For example, the crisis triggered a call for an international health systems fund to address emergencies and long-horizon health system development (Gostin 2014). A combination of national governments, regional organizations, and international finance institutions disbursed the majority of funds to aid Ebola recovery (Office of the United Nations Special Envoy on Ebola 2015). Thirty-one governments contributed at least $1 million, with the U.S., the U.K., Japan, Germany, and Canada leading the list of top contributors. Although the focus of funding was to provide emergency relief to end Ebola transmission, disbursements were also intended to stabilize and strengthen national health systems, including support for essential health services, over the long term (UNDP 2015; United States Department of State 2015; World Bank 2015). WHO provides a detailed breakdown of donations, by contributor, on its website (World Health Organization 2016c).

Political response

Ebola delivered a wake-up call to senior African health officials and political leaders around the world about the need to strengthen weak health systems in resource-constrained countries (Kaasch 2016; World Health Organization 2014b). In 2014, eleven West African health ministers initiated emergency talks to coordinate a high-level regional response (Al Jazeera 2014). Many political leaders from industrialized countries responded to the call with explicit appeals for addressing health system deficiencies. During a press conference in 2014 at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), then-President Obama cited ‘building up Africa’s public health care system’ as one of four goals of the U.S. response to Ebola in West Africa (Jackson and Szabo 2014). In preparation for the G7 meeting in 2015, the ‘Future Charter’ of the German government made explicit mention of helping the poorest countries to strengthen their health systems (Kaasch 2016). During the 70th World Health Assembly in May 2017, preparedness, surveillance, and response in health emergencies shared top agenda billing with a series of HSS topics, including the health workforce, medicines and other medical products, and research (World Health Organization 2017b).

Rhetorical response

Ebola has changed the way governments and the global health community talk about health systems and HSS. It is now increasingly difficult to find any discussion of these topics in the media, within donor governments, or in the professional literature that does not include the adjectives ‘resilient’ and/or ‘sustainable’(Kieny et al. 2014; Kruk et al. 2015; Rodin and Dahn 2015; UNICEF 2016). The Japanese government facilitated discussions around GHS, strategies to build resilient and sustainable health systems, and UHC at the 2016 G7 Summit, which it hosted (Abe 2015; Japan Center for International Exchange 2015). The title of the most recent global symposium on health systems research was ‘Resilient and Responsive Health Systems for a Changing World’ (Health Systems Global 2016). Kruk and colleagues have posited that the concept of resilience is advancing the field of health systems by introducing a dynamic dimension into more static health system models, offering new ideas from other sectors, and bridging disparate health and development agendas (Kruk et al. 2017a).

Protracted non-crisis situations: the case of the SDG for health

The global commitment to SDG3 and UHC serves as an example of how responses to protracted, non-crisis challenges can also promote HSS agenda sustainability. We believe the attributes of efforts by governments and their global health partners to address these challenges are consistent with the G&T characterization of a non-crisis situation (Table 4). The Ebola crisis re-focused the world’s attention on the status of health systems in resource-poor countries (Kaasch 2016); we posit that the pursuit of SDG3 and UHC will have a similar, although protracted, effect.

Characterization of a non-crisis situation (Grindle and Thomas) and its application to the case of the SDG for health

| Non-crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| Non-crisis situations encompass a range of largely bureaucratic events (such as the restructuring of a government ministry or administrative unit within a ministry, trade or industrial reforms, or reforms within specific sectors, such as health and education) that are perceived by middle- and lower-level government officials as having low political and economic stakes. The stakes are low because their implications relate largely to bureaucratic issues, such as careers, budgets, organizational behaviour and procedures, and agency power within government. They demand incremental, non-urgent actions. Compared with crises, the pressure for reform in a non-crisis situation is more moderate, often originating with larger groups of middle- and lower-level government bureaucrats concerned about government performance. The urgency to act is not as strong and the stakes for inaction are lower. Although non-crises do not threaten the interests of national elites, they usually are rich in micro-political and bureaucratic activity. Policy change associated with non-crisis problems is usually incremental, which often prolongs the duration of non-crisis reforms.25 |

| Case: SDG for health |

| In contrast to the Ebola response, which manifested itself largely in a highly visible public arena, the response to the challenge presented by SDG3 and UHC is unfolding in bureaucratic arenas, at both global and country levels. In contrast to the engagement of high-level political leaders throughout the world, the primary actors in the pursuit of these goals are government officials and a range of global actors working in and across government agencies, foundations, academic institutions, and others. In contrast to the urgent actions required by the pressures exerted by the Ebola crisis, global and country actors have until 2030 to achieve their aims. Failure to achieve the 2000–2015 health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) did not threaten the prestige or legitimacy of governing elites or interest groups in any country. The same is likely for the SDGs, where the stakes for non-binding consensus accords are lower (e.g., sub-optimal system and organizational performance are the principal risks). |

| Although the SDG for health envisions more cross-cutting and perhaps even more cross-sectoral approaches to global health assistance, it represents, nonetheless, an incremental step forward from previous initiatives for various reasons: (1) it embraces the unfinished agenda of the health MDGs, which focused primarily on communicable diseases and conditions;26–27 (2) it comprises concerns of particular and longstanding interest for middle-income countries, such as non-communicable diseases, substance abuse, and road injuries;28 and, (3) it revisits many of the themes of Alma Ata and the Primary Health Care Movement launched in the 1970s.29 |

| Furthermore, country government officials and global actors are not facing an unknown threat or uncertainty about how to address it: they benefit from an accumulation of existing and emergent knowledge about the performance of health systems, which normative bodies, such as the World Health Organization and the World Bank, have translated into new perspectives, templates, and guidance for how to achieve the SDG and UHC goals.30 |

| Non-crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| Non-crisis situations encompass a range of largely bureaucratic events (such as the restructuring of a government ministry or administrative unit within a ministry, trade or industrial reforms, or reforms within specific sectors, such as health and education) that are perceived by middle- and lower-level government officials as having low political and economic stakes. The stakes are low because their implications relate largely to bureaucratic issues, such as careers, budgets, organizational behaviour and procedures, and agency power within government. They demand incremental, non-urgent actions. Compared with crises, the pressure for reform in a non-crisis situation is more moderate, often originating with larger groups of middle- and lower-level government bureaucrats concerned about government performance. The urgency to act is not as strong and the stakes for inaction are lower. Although non-crises do not threaten the interests of national elites, they usually are rich in micro-political and bureaucratic activity. Policy change associated with non-crisis problems is usually incremental, which often prolongs the duration of non-crisis reforms.25 |

| Case: SDG for health |

| In contrast to the Ebola response, which manifested itself largely in a highly visible public arena, the response to the challenge presented by SDG3 and UHC is unfolding in bureaucratic arenas, at both global and country levels. In contrast to the engagement of high-level political leaders throughout the world, the primary actors in the pursuit of these goals are government officials and a range of global actors working in and across government agencies, foundations, academic institutions, and others. In contrast to the urgent actions required by the pressures exerted by the Ebola crisis, global and country actors have until 2030 to achieve their aims. Failure to achieve the 2000–2015 health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) did not threaten the prestige or legitimacy of governing elites or interest groups in any country. The same is likely for the SDGs, where the stakes for non-binding consensus accords are lower (e.g., sub-optimal system and organizational performance are the principal risks). |

| Although the SDG for health envisions more cross-cutting and perhaps even more cross-sectoral approaches to global health assistance, it represents, nonetheless, an incremental step forward from previous initiatives for various reasons: (1) it embraces the unfinished agenda of the health MDGs, which focused primarily on communicable diseases and conditions;26–27 (2) it comprises concerns of particular and longstanding interest for middle-income countries, such as non-communicable diseases, substance abuse, and road injuries;28 and, (3) it revisits many of the themes of Alma Ata and the Primary Health Care Movement launched in the 1970s.29 |

| Furthermore, country government officials and global actors are not facing an unknown threat or uncertainty about how to address it: they benefit from an accumulation of existing and emergent knowledge about the performance of health systems, which normative bodies, such as the World Health Organization and the World Bank, have translated into new perspectives, templates, and guidance for how to achieve the SDG and UHC goals.30 |

Characterization of a non-crisis situation (Grindle and Thomas) and its application to the case of the SDG for health

| Non-crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| Non-crisis situations encompass a range of largely bureaucratic events (such as the restructuring of a government ministry or administrative unit within a ministry, trade or industrial reforms, or reforms within specific sectors, such as health and education) that are perceived by middle- and lower-level government officials as having low political and economic stakes. The stakes are low because their implications relate largely to bureaucratic issues, such as careers, budgets, organizational behaviour and procedures, and agency power within government. They demand incremental, non-urgent actions. Compared with crises, the pressure for reform in a non-crisis situation is more moderate, often originating with larger groups of middle- and lower-level government bureaucrats concerned about government performance. The urgency to act is not as strong and the stakes for inaction are lower. Although non-crises do not threaten the interests of national elites, they usually are rich in micro-political and bureaucratic activity. Policy change associated with non-crisis problems is usually incremental, which often prolongs the duration of non-crisis reforms.25 |

| Case: SDG for health |

| In contrast to the Ebola response, which manifested itself largely in a highly visible public arena, the response to the challenge presented by SDG3 and UHC is unfolding in bureaucratic arenas, at both global and country levels. In contrast to the engagement of high-level political leaders throughout the world, the primary actors in the pursuit of these goals are government officials and a range of global actors working in and across government agencies, foundations, academic institutions, and others. In contrast to the urgent actions required by the pressures exerted by the Ebola crisis, global and country actors have until 2030 to achieve their aims. Failure to achieve the 2000–2015 health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) did not threaten the prestige or legitimacy of governing elites or interest groups in any country. The same is likely for the SDGs, where the stakes for non-binding consensus accords are lower (e.g., sub-optimal system and organizational performance are the principal risks). |

| Although the SDG for health envisions more cross-cutting and perhaps even more cross-sectoral approaches to global health assistance, it represents, nonetheless, an incremental step forward from previous initiatives for various reasons: (1) it embraces the unfinished agenda of the health MDGs, which focused primarily on communicable diseases and conditions;26–27 (2) it comprises concerns of particular and longstanding interest for middle-income countries, such as non-communicable diseases, substance abuse, and road injuries;28 and, (3) it revisits many of the themes of Alma Ata and the Primary Health Care Movement launched in the 1970s.29 |

| Furthermore, country government officials and global actors are not facing an unknown threat or uncertainty about how to address it: they benefit from an accumulation of existing and emergent knowledge about the performance of health systems, which normative bodies, such as the World Health Organization and the World Bank, have translated into new perspectives, templates, and guidance for how to achieve the SDG and UHC goals.30 |

| Non-crisis situations (Grindle and Thomas) |

| Non-crisis situations encompass a range of largely bureaucratic events (such as the restructuring of a government ministry or administrative unit within a ministry, trade or industrial reforms, or reforms within specific sectors, such as health and education) that are perceived by middle- and lower-level government officials as having low political and economic stakes. The stakes are low because their implications relate largely to bureaucratic issues, such as careers, budgets, organizational behaviour and procedures, and agency power within government. They demand incremental, non-urgent actions. Compared with crises, the pressure for reform in a non-crisis situation is more moderate, often originating with larger groups of middle- and lower-level government bureaucrats concerned about government performance. The urgency to act is not as strong and the stakes for inaction are lower. Although non-crises do not threaten the interests of national elites, they usually are rich in micro-political and bureaucratic activity. Policy change associated with non-crisis problems is usually incremental, which often prolongs the duration of non-crisis reforms.25 |

| Case: SDG for health |

| In contrast to the Ebola response, which manifested itself largely in a highly visible public arena, the response to the challenge presented by SDG3 and UHC is unfolding in bureaucratic arenas, at both global and country levels. In contrast to the engagement of high-level political leaders throughout the world, the primary actors in the pursuit of these goals are government officials and a range of global actors working in and across government agencies, foundations, academic institutions, and others. In contrast to the urgent actions required by the pressures exerted by the Ebola crisis, global and country actors have until 2030 to achieve their aims. Failure to achieve the 2000–2015 health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) did not threaten the prestige or legitimacy of governing elites or interest groups in any country. The same is likely for the SDGs, where the stakes for non-binding consensus accords are lower (e.g., sub-optimal system and organizational performance are the principal risks). |

| Although the SDG for health envisions more cross-cutting and perhaps even more cross-sectoral approaches to global health assistance, it represents, nonetheless, an incremental step forward from previous initiatives for various reasons: (1) it embraces the unfinished agenda of the health MDGs, which focused primarily on communicable diseases and conditions;26–27 (2) it comprises concerns of particular and longstanding interest for middle-income countries, such as non-communicable diseases, substance abuse, and road injuries;28 and, (3) it revisits many of the themes of Alma Ata and the Primary Health Care Movement launched in the 1970s.29 |

| Furthermore, country government officials and global actors are not facing an unknown threat or uncertainty about how to address it: they benefit from an accumulation of existing and emergent knowledge about the performance of health systems, which normative bodies, such as the World Health Organization and the World Bank, have translated into new perspectives, templates, and guidance for how to achieve the SDG and UHC goals.30 |

During the next two decades, the pursuit of SDG3 and UHC will continue to engage a range of local and global actors. How will what transpires at local levels, through different processes and at varying pace, repeated and dispersed over multiple countries, influence HSS’s position on the global policy agenda? In Table 5, we describe three promising translational mechanisms: global monitoring, learning networks, and high-level consultations. Similar to their response to Ebola, global actors and country officials are mobilizing, or are likely to mobilize, important technical, managerial, financial, and political resources to boost HSS’s role in facilitating countries’ progress toward achievement of SDG3 and UHC.

HSS global agenda sustainability: translational mechanisms associated with SDG3 and UHC

| Monitoring | WHO and The World Bank are tracking global progress toward UHC. They jointly issued the first global monitoring report in 2015.31 Multiple websites exist to monitor implementation.32–35 |

| Learning | The Joint Learning Network and the P4H Social Health Protection Network, which function at global and country levels, are ensuring coordination among development partners around technical assistance for UHC and HSS.36–37 They also are building strong support networks to ensure local country practitioners can share knowledge and expertise. Regional platforms, such as the Asia-Pacific Network for Health Systems Strengthening (ANHSS), are addressing the need for knowledge improvement and exchange around HSS in the Asia region.38 |

| High-level consultations | High-level meetings on UHC, such as the WHO/World Bank Ministerial-level Meeting in 2013 in Geneva,39 and the bi-annual global symposia on health systems research that Health Systems Global has been organizing since 2010,40 provide fora that facilitate the exchange of experiences occurring at national and regional levels. |

| Monitoring | WHO and The World Bank are tracking global progress toward UHC. They jointly issued the first global monitoring report in 2015.31 Multiple websites exist to monitor implementation.32–35 |

| Learning | The Joint Learning Network and the P4H Social Health Protection Network, which function at global and country levels, are ensuring coordination among development partners around technical assistance for UHC and HSS.36–37 They also are building strong support networks to ensure local country practitioners can share knowledge and expertise. Regional platforms, such as the Asia-Pacific Network for Health Systems Strengthening (ANHSS), are addressing the need for knowledge improvement and exchange around HSS in the Asia region.38 |

| High-level consultations | High-level meetings on UHC, such as the WHO/World Bank Ministerial-level Meeting in 2013 in Geneva,39 and the bi-annual global symposia on health systems research that Health Systems Global has been organizing since 2010,40 provide fora that facilitate the exchange of experiences occurring at national and regional levels. |

HSS global agenda sustainability: translational mechanisms associated with SDG3 and UHC

| Monitoring | WHO and The World Bank are tracking global progress toward UHC. They jointly issued the first global monitoring report in 2015.31 Multiple websites exist to monitor implementation.32–35 |

| Learning | The Joint Learning Network and the P4H Social Health Protection Network, which function at global and country levels, are ensuring coordination among development partners around technical assistance for UHC and HSS.36–37 They also are building strong support networks to ensure local country practitioners can share knowledge and expertise. Regional platforms, such as the Asia-Pacific Network for Health Systems Strengthening (ANHSS), are addressing the need for knowledge improvement and exchange around HSS in the Asia region.38 |

| High-level consultations | High-level meetings on UHC, such as the WHO/World Bank Ministerial-level Meeting in 2013 in Geneva,39 and the bi-annual global symposia on health systems research that Health Systems Global has been organizing since 2010,40 provide fora that facilitate the exchange of experiences occurring at national and regional levels. |

| Monitoring | WHO and The World Bank are tracking global progress toward UHC. They jointly issued the first global monitoring report in 2015.31 Multiple websites exist to monitor implementation.32–35 |

| Learning | The Joint Learning Network and the P4H Social Health Protection Network, which function at global and country levels, are ensuring coordination among development partners around technical assistance for UHC and HSS.36–37 They also are building strong support networks to ensure local country practitioners can share knowledge and expertise. Regional platforms, such as the Asia-Pacific Network for Health Systems Strengthening (ANHSS), are addressing the need for knowledge improvement and exchange around HSS in the Asia region.38 |

| High-level consultations | High-level meetings on UHC, such as the WHO/World Bank Ministerial-level Meeting in 2013 in Geneva,39 and the bi-annual global symposia on health systems research that Health Systems Global has been organizing since 2010,40 provide fora that facilitate the exchange of experiences occurring at national and regional levels. |

Technical/managerial response

Technical and managerial feedback from the 15-year pursuit (2000–2015) of the health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) identified weak, under-funded health systems as a major impediment to their achievement (Bellagio Study Group on Child Survival 2003; Fox and Reich 2015; Fryatt et al. 2010; Requejo et al. 2015; UNAIDS 2015; van Olmen et al. 2012). Of the 75 countries UNICEF and WHO defined as MDG priorities, only 33% achieved MDG4 (Child health), and 8% MDG5 (Maternal health). Only four of the 75 countries (5%) achieved both MDGs 4 and 5 (Requejo et al. 2015). Failure to achieve the MDGs cannot be attributed to under-performing health systems alone; conflict, poverty, poor governance, and other socio-economic and political factors all influenced the outcome, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. But increasing recognition by technical experts and managers of the role of health system performance as one among many critical factors in achieving a global development goal should contribute not only to HSS’s continuing place of prominence, but could also influence how progress toward SDG3 will be measured and monitored at global level. Seidman recently mapped SDG3 indicators to a theory of change for health systems performance (Seidman 2017).

LMICs’ pursuit of the MDGs also highlighted the role HSS must play in ensuring access to essential health services for all segments of the population in the context of SDG3 and UHC. Despite the many benefits associated with the pursuit of the MDGs (United Nations 2015), there is strong evidence that the poorest and most disadvantaged in many countries are still shouldering a disproportionate share of the ill-health burden and have less access to essential health services than wealthier people (Gwatkin et al. 2005; Victora et al. 2003; World Bank 2004). To ensure that the pursuit of UHC promotes equity in terms of technical and managerial health system inputs and outcomes, Gwatkin and Ergo propose ‘progressive universalism,’ an approach that ‘ensures people who are poor gain at least as much as those who are better off at every step of the way toward universal coverage, rather than having to wait and catch up as that goal is eventually approached’ (Gwatkin and Ergo 2011). Gwatkin and Ergo cite Brazil’s Family Health Program and Mexico’s Seguro Popular initiative as successful examples of this ‘progressive’ approach to health systems improvement—serving initially those most in need. Carrera and colleagues found that an equity-focused approach may be more cost-effective than mainstream approaches in improving child health and nutrition outcomes, while reducing intervention coverage and out-of-pocket spending inequities (between the most and least deprived groups and geographic areas within countries) (Carrera et al. 2012). Many LMICs will likely require donor technical assistance and investment that align with a country’s goal of progressive universalism, as they did during the MDG era.

Financing response

Experts believe that SDG3 and UHC, in particular, have the potential to become important policy drivers for HSS in LMICs and for directing future donor investments (GBD 2015 SDG Collaborators 2016). The goal and target could serve as meaningful signalling devices for keeping HSS at the center of the global health policy dialogue. Munir and Worm recently concluded from their analysis that the U.S. and U.K. are aligning their HSS investments with SDG3 and UHC, while encouraging technical and financial collaboration among development partners (Munir and Worm 2016). By increasingly incorporating the UHC goal in their national health sector plans and health financing strategies (Lagomarsino et al. 2012; Reich et al. 2016), countries may facilitate a flow of multilateral, bilateral, non-governmental, and other donor financial support to HSS to ensure better alignment of assistance with national priorities.

Political response

A combination of factors—the extent of the network of global actors (Hoffman et al. 2015), the number and sometimes overlapping mandates and tasks they embrace (Hoffman et al. 2015; Lee et al. 1996), and calls for more efficient global health governance and the challenges that such calls present (Frenk and Moon 2013; Harman 2012)—fosters an environment at global level conducive to intense micro-political transactions. These micro-political transactions affecting HSS will also become apparent in Geneva and elsewhere as the new WHO Director-General attempts to make good on his commitment to UHC as his top priority (The Lancet Global Health 2017). Fox and Reich recently developed a framework for evaluating and addressing the politics of UHC in LMICs (Fox and Reich 2015).

The literature on path dependency has demonstrated that once an entity embarks on a chosen path, certain institutional arrangements emerge over time to embed a particular way of thinking and doing within the entity (Powell and DiMaggio 1991). Changing course and choosing alternative paths—even ones that might be more efficient—often entail high costs and can generate considerable resistance from entrenched interest groups with strong incentives to maintain the status quo (Powell and DiMaggio 1991). As one observer has noted, the SDGs will ‘lock in the global development agenda for the next fifteen years’ (Hickel 2015). Regardless of implementation adequacy at country level, or whether SDG3 successfully improves the health and well-being of the millions of people it targets, the perception of HSS as a key driver for ensuring progress toward a consensus goal is likely to help it maintain a secure place on the global agenda.

Emerging evidence about health system change

We posit that continuing efforts to share evidence about how to manage health system reforms; to synthesize and generate evidence of HSS’s effects; and to support the production of global knowledge will contribute to keeping HSS at the centre of discussions about how best to respond to crisis and non-crisis events.

Evidence sharing around how to manage health system reforms

The World Bank has characterized UHC as necessitating system-wide, transformational reforms (Cotlear et al. 2015; Maeda et al. 2014), because it requires comprehensive, intentional actions on many inter-related fronts—political, economic, social, and technocratic. If UHC requires a health system transformation, then the HSS global policy community and policy makers in LMICs will need knowledge about how to manage complex, large-scale health system reforms. Three recent compilations of World Bank case studies (Cotlear et al. 2015; Dmytraczenko and Almeida 2015; Maeda et al. 2014), all of which examined efforts of countries around the world to move towards UHC, are essential resources.

In addition, some of the factors that have been consequential in health system transformation in Central Asia during the last 20 years provide additional insights into the practice of large-scale, comprehensive HSS (Abt Associates 2015). For example, unlike many of the countries that have engaged in UHC reforms in the last decade—a number of which are struggling to achieve basic health service coverage for their populations—in the early 1990 s the then-newly independent countries of the former Soviet Union faced a significant systemic challenge of inferior health care service quality (Abt Associates 2015). The Central Asia experience in improving quality of care, including how development partners collaborated in promoting progress, offers an important set of insights that address concerns that some UHC observers have expressed about quality (Lindelow et al. 2015).

Finally, some important comparative systems research has identified the characteristics of successful health system change at scale that could inform country policies and practices (Balabanova et al. 2013). For example, four characteristics of successful change that Balabanova and colleagues identified in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Thailand, and Tamil Nadu were good governance and political commitment; effective bureaucracies and institutions; ability to innovate, especially with respect to service delivery; and resilience. The December 2014 launch of the journal Health Systems and Reform (HS&R), whose objective is to serve as ‘a global platform for sharing cutting-edge analysis, methods, and lessons in health systems and reform…’ will further promote knowledge transfer about the most recent advances in HSS (Antoun and Reich 2015).

HSS evidence synthesis and generation

In 2015, Hatt and colleagues reviewed the impact of HSS interventions—encompassing a wide range of purposeful change strategies, policies, regulations, programs, and activities—on health outcomes in LMICs (Hatt et al. 2015). The review sought to identify documented effects of such interventions on health status (including mortality, morbidity, life expectancy, fertility, nutritional status, fertility, and DALYs) and health status proxies (including service utilization, service provision, uptake of healthy behaviors, and financial protection) through a review of systematic reviews. The investigators identified 13 HSS interventions with documented effects (Table 6), and concluded that there was substantial, available quantitative evidence linking these interventions with positive health impacts and health system outcomes. They also found that innovations and reforms in how and where health services are delivered, how they are organized and financed, and who delivers them can improve the health of populations in LMICs.

Summary results of the review of published reviews: documented effects of 13 types of HSS interventions41

| Health impacts and health system outcome measures . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of interventions . | Improved service provision/quality . | Increased financial protection . | Increased service utilization . | Uptake of healthy behaviors . | Reduced morbidity, mortality . |

| Accountability and engagement interventions | X | X | X | X | |

| Conditional cash transfers | X | X | X | ||

| Contracting out service provision | X | X | X | ||

| Health insurance | X | X | X | ||

| Health worker training to improve service delivery | X | X | X | ||

| Information technology supports (m-health/e-health) | X | X | |||

| Pharmaceutical systems strengthening | X | ||||

| Service integration | X | X | X | ||

| Strengthening health services at the community level | X | X | X | ||

| Supply-side performance-based financing | X | X | |||

| Task sharing/shifting | X | X | |||

| User fee exemptions | X | ||||

| Voucher programs | X | X | X | X | |

| Health impacts and health system outcome measures . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of interventions . | Improved service provision/quality . | Increased financial protection . | Increased service utilization . | Uptake of healthy behaviors . | Reduced morbidity, mortality . |

| Accountability and engagement interventions | X | X | X | X | |

| Conditional cash transfers | X | X | X | ||

| Contracting out service provision | X | X | X | ||

| Health insurance | X | X | X | ||

| Health worker training to improve service delivery | X | X | X | ||

| Information technology supports (m-health/e-health) | X | X | |||

| Pharmaceutical systems strengthening | X | ||||

| Service integration | X | X | X | ||

| Strengthening health services at the community level | X | X | X | ||

| Supply-side performance-based financing | X | X | |||

| Task sharing/shifting | X | X | |||

| User fee exemptions | X | ||||

| Voucher programs | X | X | X | X | |

Summary results of the review of published reviews: documented effects of 13 types of HSS interventions41

| Health impacts and health system outcome measures . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of interventions . | Improved service provision/quality . | Increased financial protection . | Increased service utilization . | Uptake of healthy behaviors . | Reduced morbidity, mortality . |

| Accountability and engagement interventions | X | X | X | X | |

| Conditional cash transfers | X | X | X | ||

| Contracting out service provision | X | X | X | ||

| Health insurance | X | X | X | ||

| Health worker training to improve service delivery | X | X | X | ||

| Information technology supports (m-health/e-health) | X | X | |||

| Pharmaceutical systems strengthening | X | ||||

| Service integration | X | X | X | ||

| Strengthening health services at the community level | X | X | X | ||

| Supply-side performance-based financing | X | X | |||

| Task sharing/shifting | X | X | |||

| User fee exemptions | X | ||||

| Voucher programs | X | X | X | X | |

| Health impacts and health system outcome measures . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of interventions . | Improved service provision/quality . | Increased financial protection . | Increased service utilization . | Uptake of healthy behaviors . | Reduced morbidity, mortality . |

| Accountability and engagement interventions | X | X | X | X | |

| Conditional cash transfers | X | X | X | ||

| Contracting out service provision | X | X | X | ||

| Health insurance | X | X | X | ||

| Health worker training to improve service delivery | X | X | X | ||

| Information technology supports (m-health/e-health) | X | X | |||

| Pharmaceutical systems strengthening | X | ||||

| Service integration | X | X | X | ||

| Strengthening health services at the community level | X | X | X | ||

| Supply-side performance-based financing | X | X | |||

| Task sharing/shifting | X | X | |||

| User fee exemptions | X | ||||

| Voucher programs | X | X | X | X | |

Advancing the HSS evidence agenda is not limited to improving our understanding of transformational, so-called ‘big bang’ reforms, such as UHC (Cotlear et al. 2015; Fox and Reich 2015), but also of purposeful, HSS change strategies or interventions at more meso and micro levels. This is important because movement towards UHC in lower-income countries is still modest (Lagomarsino et al. 2012). Many countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa, are not yet in a position to undertake comprehensive reforms, because they do not have all the institutional, technical, political, and financial resources necessary to pursue such changes at scale. Nevertheless, feasible cross-cutting interventions that affect the functioning of multiple health programs with the potential to sustain their short-term gains (Travis et al. 2004) provide, in accordance with organizational theory, a platform for transformational change and the means to institutionalize it (Weick and Quinn 1999).