-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

M Douine, Y Lazrek, D Blanchet, S Pelleau, R Chanlin, F Corlin, L Hureau, B Volney, H Hiwat, S Vreden, F Djossou, M Demar, M Nacher, L Musset, Predictors of antimalarial self-medication in illegal gold miners in French Guiana: a pathway towards artemisinin resistance, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 73, Issue 1, January 2018, Pages 231–239, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx343

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Malaria is endemic in French Guiana (FG), South America. Despite the decrease in cases in the local population, illegal gold miners are very affected by malaria (22.3% of them carried Plasmodium spp.). Self-medication seems to be very common, but its modalities and associated factors have not been studied. The aim of this study was to evaluate parasite susceptibility to drugs and to document behaviours that could contribute to resistance selection in illegal gold miners.

This multicentric cross-sectional study was conducted in resting sites along the FG–Surinamese border. Participating gold miners working in FG completed a questionnaire and provided a blood sample.

From January to June 2015, 421 illegal gold miners were included. Most were Brazilian (93.8%) and 70.5% were male. During the most recent malaria attack, 45.5% reported having been tested for malaria and 52.4% self-medicated, mainly with artemisinin derivatives (90%). Being in FG during the last malaria attack was the main factor associated with self-medication (adjusted OR = 22.1). This suggests that access to malaria diagnosis in FG is particularly difficult for Brazilian illegal gold miners. Treatment adherence was better for persons who reported being tested. None of the 32 samples with Plasmodium falciparum presented any mutation on the pfK13 gene, but one isolate showed a resistance profile to artemisinin derivatives in vitro.

The risk factors for the selection of resistance are well known and this study showed that they are present in FG with persons who self-medicated with poor adherence. Interventions should be implemented among this specific population to avoid the emergence of artemisinin resistance.

Introduction

Malaria is a major parasitic illness, with 198 million cases and 584000 deaths in 2014, worldwide.1 In French Guiana (FG), a French overseas territory located on the Guiana Shield in South America, malaria is endemic.2 Great efforts have been deployed to control malaria in the region. In Suriname as in local villages in FG, the number of cases decreased drastically.3,4 But in this territory, mainly covered by Amazonian forest, the soil is rich in gold. In addition to the legal mining industry, 8000–10 000 illegal gold miners, mainly Brazilian, work in the forest.5 They have difficult life conditions with poor hygiene and exhausting work, which lead to poor health. Deforestation and still water pools favour mosquito proliferation, notably Anopheles darlingi, the main malaria vector. In 2015, in western FG, molecular malaria diagnosis showed 22.3% of illegal gold miners carried Plasmodium spp., 84% of whom were asymptomatic.6 In 2014, in a gold mining site near Maripa Soula, 48.5% of gold miners were positive for Plasmodium spp. by PCR.7 This indicated that although malaria in local populations keeps decreasing, it remains hyperendemic in this specific population in FG. Medical care is free in health centres, but the remoteness of the mines and the fear of law enforcement hamper effective access to care for miners. A first study in this population in Suriname and FG has shown that self-medication with artemisinin derivatives seemed to be very common, with poor treatment adherence.8 But self-medication modes and factors associated with it have not been studied specifically in FG despite access to care differences between those two countries. This frequent self-medication threatens the efficacy of artemisinin derivatives. In fact, the main known factors contributing to antimalarial drug resistance are: poor treatment adherence (quantity or treatment duration), poor quality of drugs and drug pressure with monotherapy.9,10 Historically, antimalarial drug resistance emerged independently, in South-East Asia and in the Amazon region, as it happened for chloroquine resistance in the 1960s.11,12 The decrease in susceptibility to artemisinin derivatives appeared about 10 years ago in South-East Asia and now concerns five countries in the Mekong Region.13–15 The transborder context between Suriname, Brazil and FG, with movements of precarious populations in remote areas, challenges malaria control in this area and is similar to the transborder context of the Mekong Region.16

Several parameters are used to characterize artemisinin resistance. In vivo, the persistence of parasites in the blood more than three days after treatment or a delayed parasite clearance time are indicators.17,In vitro, the survival rate of ring-stage parasites that have been exposed for six hours to dihydroartemisinin is the best phenotyping method to identify a decreased parasite susceptibility to dihydroartemisinin.18 Finally in 2013, certain mutations in the pfK13 gene were shown to be associated with an increased parasite clearance time in isolates from South-East Asia.19

The objectives of this study were to describe the behaviours of illegal gold miners working in FG when they have had a malaria attack; to evaluate factors associated with self-medication and with poor treatment adherence; and to characterize artemisinin susceptibility of the associated parasites.

Methods

A multicentric cross-sectional observational study was conducted in 2015 between 1 January and 30 June. As no sampling frame exists, illegal gold miners were recruited using convenience and snow-ball sampling on ‘resting sites’, informal areas where they go for rest, supplies or medical care. These sites were spread along the FG–Surinamese border on the Maroni river.

Inclusion criteria were: working on a gold mining site in FG; being at the resting site for less than 7 days; being over 18 years of age; and giving informed consent. A questionnaire collected socio-demographic data, knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) in gold miners concerning malaria. Behaviour when having malaria referred to the last malaria episode only, to avoid memory bias. Poor adherence was considered if the person declared that there were remaining pills at the end of the last malaria treatment. A rapid diagnostic test was performed in the field and malaria treatment was given if the test was positive. A 5 mL blood sample was taken from each participant and sent to the National Reference Center for Malaria for biological investigations. If the thin smear was positive for Plasmodium falciparum, parasites were phenotyped using the standard isotopic method and the ring survival assay (RSA).18–20 DNA was extracted from 200 μL of whole blood with the QIA amp® DNA kit (Qiagen). The pfK13 gene was amplified and sequenced using the Sanger method.19 Study size and bias assessment are described in Douine et al.6

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed with Stata12 software (StataCorp©, College Station, TX, USA). Data from the KAP study were analysed using multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) in order to reduce the dimension of the variables. Ascending hierarchical classification (AHC) was used to define clusters with similar characteristics; individuals were grouped in clusters using variables selected from the MCA, namely those with higher weights on MCA. Bivariate analysis was done using χ2 tests or Student’s t-test depending on the type of variable. Variables with a P value <0.20 in bivariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression to identify factors associated with self-medication and poor treatment adherence. A backward selection method was used to retain variables significant at a 0.05 level in the final multivariate model. The goodness of fit of the logistical regression model was tested with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. All statistical analyses used a 5% significance level.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Comité d’Evaluation Ethique de l’Inserm, Process n°14–187 (IRB00003888 FWA00005831). The database was anonymized and declared to the Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés. Patients were included after recording informed consent.

Results

Study population

From January to June 2015, 421 illegal gold miners were included in the study with a participation rate of 90.5%.6 The mean age was 37.7 years (min.–max. = 18–62) and 70.5% of participants were men. Most of them (93.8%) were born in Brazil and they worked in 67 different mining sites.

Malaria knowledge and protection

Malaria was mentioned in the top three health problems at mining sites by 84.8% of interviewed people. The mode of transmission was well known: 91.4% mentioned the mosquito, but 3.3% mentioned living near dirty water or 3.3% in a dirty environment or 1.6% drinking dirty water. One-hundred and twenty-eight (30.4%) considered that it was better to take treatment even if the malaria test was negative, 11.2% considered that treatment could be stopped when feeling better and 8.5% considered that malaria could be cured without treatment. Most (95.7%) thought that malaria kills. French malaria treatment was considered better than Surinamese treatment for 93% of them, and better than Brazilian treatment for 84%. However, the three treatments are in fact the same: artemether-lumefantrine, labelled as Riamet® in France and Coartem® in Brazil or Suriname. The majority of interviewed people (85.5%) could mention three or more malaria symptoms.

Considering malaria protection, 18% declared protecting themselves from malaria always or often, but 54.8% never. The modes of protection were: mosquito nets (29%), mosquito repellents (21.6%), wearing long clothes (2.1%) and living far from dirty water (1.2%). However, only 15.7% declared having slept under a mosquito net the last night at the mining camp, of which only 19.7% were insecticide-treated nets. The main reasons for not using a mosquito net were: did not have any (63.4%), uncomfortable (19.1%), destroyed by French Army (10.4%) (military operations against illegal gold mining aim at destroying all logistical supplies on mining camps), too constraining (7.9%), useless (5.6%) and would hamper flight in the event of a military raid in the camp (3.4%). Malaria chemoprophylaxis was used by 6.4% of people, mainly with Artecom® (dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine/trimethoprim + primaquine single dose).

Past malaria history and behaviours

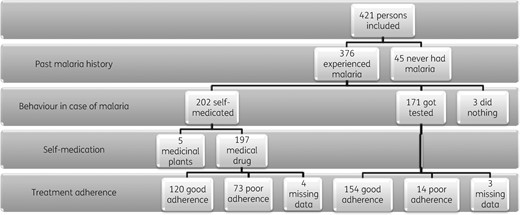

The flow chart is presented Figure 1. Forty-five persons (10.7%) declared never having had malaria. They differed from the 376 people who declared a past history of malaria for sex (51% of males in persons who never had malaria versus 73% in persons with a past history of malaria; P = 0.002), age (31% more than 37 years versus 52%; P = 0.009), but the place of birth did not differ. Most participants (66.2%) declared having had more than seven malaria attacks, and 24.2% three or less. The median time since the last malaria attack was 2 years (IQR = 6 months–6 years). During the last malaria attack, 52.4% (n = 197) self-medicated with antimalarial drugs, 45.5% (n = 171) got tested for malaria, 1.3% (n = 5) used medicinal plants and 0.8% (n = 3) declared having done nothing, without statistical difference between groups for socio-demographic variables. When only considering people having had their last malaria attack less than 2 years ago, 66% took the whole treatment and 66.5% self-medicated, compared with 86.7% and 39.3% for those who had malaria more than 2 years ago, respectively (P < 0.001 for both). Behaviour also varied with the place of the last malaria attack: 66% of self-medication if in FG, 28% if in Suriname and 7% if in Brazil (P < 0.001).

Flow chart of the study. In our region, free medication is given to all persons who are tested positive for malaria so getting tested for malaria and self-medication are mutually exclusive categories.

Malaria testing

For persons who got tested for malaria (n = 171), the testing location depended on the country where the malaria attack occurred. If malaria occurred in Brazil (n = 56) or Suriname (n = 18), people got tested in these countries. But if malaria occurred in FG (n = 86), 47.7% went to Suriname to get tested [33 people went to a health centre, 8 to Malaria Service Deliverers (MSD)], 37.2% to a French health centre and 12.8% went back to Brazil. The two other people (2.3%) declared having been tested by Surinamese MSD at a mining site in FG. Easy accessibility was the main reason declared for choosing a place for malaria diagnosis and treatment (85.9%). Care was free for 87.7% of the surveyed miners. Treatment effectiveness was perceived to be good for 93.6%, and 90% declared having taken the complete treatment course.

Self-medication

A majority of those who reported self-medication (n = 197) bought antimalarial drugs directly on the mining site (80.7%), or got it from friends or family (6.1%). Ninety percent (178/197) of antimalarial drugs contained artemisinin derivatives, of which 93.8% were Artecom®. Most of the time (85.1%), the treatment was paid for in gold, 1 – 3 g, which is worth 30–90 USD. Treatment effectiveness was considered to be good for 68%, but insufficient for 23.9%. One-hundred and twenty persons (60.9%) declared having taken the whole treatment. The majority (93.4%) declared that self-medication was related to the distance of malaria testing structures. After multivariate analysis, the main variables significantly associated with self-medication were being in FG during the last malaria attack [adjusted OR (AOR) = 22.1] and being born in Brazil (AOR = 10.74) (Table 1).

Logistic regression model for factors associated with self-medication in illegal gold miners working in FG, 2015 (n/N = 202/373)

| . | Self-medication, n/N (%) . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| agec | |||||

| ≤38 years | 98/178 (55.06) | 1 | 0.739 | 1 | 0.384 |

| >38 years | 104/195 (53.33) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | ||

| sexc | |||||

| female | 57/101 (56.44) | 1 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.770 |

| male | 145/272 (53.31) | 0.88 (0.56–1.40) | 1.09 (0.61–1.96) | ||

| country of birth | |||||

| other than Brazil | 3/21 (14.29) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Brazil | 199/352 (56.53) | 7.8 (2.26–26.98) | 10.74 (2.82–40.82) | ||

| countries of work in the last 3 yearsd | |||||

| FG and others | 47/115 (40.87) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.016 |

| FG only | 155/258 (60.08) | 2.18 (1.39–3.41) | 2 (1.14–3.55) | ||

| Attitude and knowledge | |||||

| malaria is a major health probleme | |||||

| no | 19/55 (34.55) | 1 | 0.001 | ||

| yes | 183/318 (57.55) | 2.57 (1.41–4.67) | |||

| better to treat even if test negativef | |||||

| no | 133/263 (50.57) | 1 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.039 |

| yes | 69/110 (62.73) | 1.64 (1.04–2.59) | 1.82 (1.03–3.22) | ||

| malaria stays all lifeg | |||||

| no | 148/287 (51.57) | 1 | 0.065 | ||

| yes | 54/86 (62.79) | 1.58 (0.97–2.60) | |||

| cure without treatmenth | |||||

| no | 180/342 (52.63) | 1 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.036 |

| yes | 22/31 (70.97) | 2.2 (0.98–4.92) | 3.19 (1.08–9.46) | ||

| protection against mosquitoes | |||||

| sometimes/never | 177/315 (56.19) | 1 | 0.066 | ||

| always/often | 25/58 (43.10) | 0.59 (0.34–1.04) | |||

| Clinical data | |||||

| past history of malaria | |||||

| ≤3 malaria attacks | 30/91 (32.97) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.005 |

| ≥4 malaria attacks | 172/282 (60.99) | 3.18 (1.93–5.23) | 2.47 (1.31–4.64) | ||

| date of last malaria attack | |||||

| ≤2 years | 130/194 (67.01) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.028 |

| >2 years | 72/179 (40.22) | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–1) | ||

| place when last malaria attack | |||||

| Brazil | 4/60 (6.67) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| FG | 188/274 (68.61) | 30.60 (10.75–87.11) | 22.1 (7.39–66.04) | <0.001 | |

| other | 10/39 (25.64) | 4.82 (1.39–16.74) | 6.11 (1.60–23.4) | 0.008 | |

| Plasmodium spp. PCR | |||||

| negative | 162/286 (56.64) | 1 | 0.081 | 1 | 0.002 |

| positive | 40/87 (45.98) | 0.65 (0.40–1.05) | 0.37 (0.20–0.68) | ||

| . | Self-medication, n/N (%) . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| agec | |||||

| ≤38 years | 98/178 (55.06) | 1 | 0.739 | 1 | 0.384 |

| >38 years | 104/195 (53.33) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | ||

| sexc | |||||

| female | 57/101 (56.44) | 1 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.770 |

| male | 145/272 (53.31) | 0.88 (0.56–1.40) | 1.09 (0.61–1.96) | ||

| country of birth | |||||

| other than Brazil | 3/21 (14.29) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Brazil | 199/352 (56.53) | 7.8 (2.26–26.98) | 10.74 (2.82–40.82) | ||

| countries of work in the last 3 yearsd | |||||

| FG and others | 47/115 (40.87) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.016 |

| FG only | 155/258 (60.08) | 2.18 (1.39–3.41) | 2 (1.14–3.55) | ||

| Attitude and knowledge | |||||

| malaria is a major health probleme | |||||

| no | 19/55 (34.55) | 1 | 0.001 | ||

| yes | 183/318 (57.55) | 2.57 (1.41–4.67) | |||

| better to treat even if test negativef | |||||

| no | 133/263 (50.57) | 1 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.039 |

| yes | 69/110 (62.73) | 1.64 (1.04–2.59) | 1.82 (1.03–3.22) | ||

| malaria stays all lifeg | |||||

| no | 148/287 (51.57) | 1 | 0.065 | ||

| yes | 54/86 (62.79) | 1.58 (0.97–2.60) | |||

| cure without treatmenth | |||||

| no | 180/342 (52.63) | 1 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.036 |

| yes | 22/31 (70.97) | 2.2 (0.98–4.92) | 3.19 (1.08–9.46) | ||

| protection against mosquitoes | |||||

| sometimes/never | 177/315 (56.19) | 1 | 0.066 | ||

| always/often | 25/58 (43.10) | 0.59 (0.34–1.04) | |||

| Clinical data | |||||

| past history of malaria | |||||

| ≤3 malaria attacks | 30/91 (32.97) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.005 |

| ≥4 malaria attacks | 172/282 (60.99) | 3.18 (1.93–5.23) | 2.47 (1.31–4.64) | ||

| date of last malaria attack | |||||

| ≤2 years | 130/194 (67.01) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.028 |

| >2 years | 72/179 (40.22) | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–1) | ||

| place when last malaria attack | |||||

| Brazil | 4/60 (6.67) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| FG | 188/274 (68.61) | 30.60 (10.75–87.11) | 22.1 (7.39–66.04) | <0.001 | |

| other | 10/39 (25.64) | 4.82 (1.39–16.74) | 6.11 (1.60–23.4) | 0.008 | |

| Plasmodium spp. PCR | |||||

| negative | 162/286 (56.64) | 1 | 0.081 | 1 | 0.002 |

| positive | 40/87 (45.98) | 0.65 (0.40–1.05) | 0.37 (0.20–0.68) | ||

Hosmer–Lemeshow test: P = 0.507.

Obtained from the likelihood ratio test.

Age and sex were forced.

Countries where people worked for gold mining in the last 3 years.

Considering malaria as a major health problem on mining sites.

Thinking that it is better to take a malaria treatment even if the malaria test is negative, just to be sure.

Thinking that malaria stays all life in the body.

Thinking that malaria can be cured without treatment.

Logistic regression model for factors associated with self-medication in illegal gold miners working in FG, 2015 (n/N = 202/373)

| . | Self-medication, n/N (%) . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| agec | |||||

| ≤38 years | 98/178 (55.06) | 1 | 0.739 | 1 | 0.384 |

| >38 years | 104/195 (53.33) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | ||

| sexc | |||||

| female | 57/101 (56.44) | 1 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.770 |

| male | 145/272 (53.31) | 0.88 (0.56–1.40) | 1.09 (0.61–1.96) | ||

| country of birth | |||||

| other than Brazil | 3/21 (14.29) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Brazil | 199/352 (56.53) | 7.8 (2.26–26.98) | 10.74 (2.82–40.82) | ||

| countries of work in the last 3 yearsd | |||||

| FG and others | 47/115 (40.87) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.016 |

| FG only | 155/258 (60.08) | 2.18 (1.39–3.41) | 2 (1.14–3.55) | ||

| Attitude and knowledge | |||||

| malaria is a major health probleme | |||||

| no | 19/55 (34.55) | 1 | 0.001 | ||

| yes | 183/318 (57.55) | 2.57 (1.41–4.67) | |||

| better to treat even if test negativef | |||||

| no | 133/263 (50.57) | 1 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.039 |

| yes | 69/110 (62.73) | 1.64 (1.04–2.59) | 1.82 (1.03–3.22) | ||

| malaria stays all lifeg | |||||

| no | 148/287 (51.57) | 1 | 0.065 | ||

| yes | 54/86 (62.79) | 1.58 (0.97–2.60) | |||

| cure without treatmenth | |||||

| no | 180/342 (52.63) | 1 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.036 |

| yes | 22/31 (70.97) | 2.2 (0.98–4.92) | 3.19 (1.08–9.46) | ||

| protection against mosquitoes | |||||

| sometimes/never | 177/315 (56.19) | 1 | 0.066 | ||

| always/often | 25/58 (43.10) | 0.59 (0.34–1.04) | |||

| Clinical data | |||||

| past history of malaria | |||||

| ≤3 malaria attacks | 30/91 (32.97) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.005 |

| ≥4 malaria attacks | 172/282 (60.99) | 3.18 (1.93–5.23) | 2.47 (1.31–4.64) | ||

| date of last malaria attack | |||||

| ≤2 years | 130/194 (67.01) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.028 |

| >2 years | 72/179 (40.22) | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–1) | ||

| place when last malaria attack | |||||

| Brazil | 4/60 (6.67) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| FG | 188/274 (68.61) | 30.60 (10.75–87.11) | 22.1 (7.39–66.04) | <0.001 | |

| other | 10/39 (25.64) | 4.82 (1.39–16.74) | 6.11 (1.60–23.4) | 0.008 | |

| Plasmodium spp. PCR | |||||

| negative | 162/286 (56.64) | 1 | 0.081 | 1 | 0.002 |

| positive | 40/87 (45.98) | 0.65 (0.40–1.05) | 0.37 (0.20–0.68) | ||

| . | Self-medication, n/N (%) . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| agec | |||||

| ≤38 years | 98/178 (55.06) | 1 | 0.739 | 1 | 0.384 |

| >38 years | 104/195 (53.33) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | ||

| sexc | |||||

| female | 57/101 (56.44) | 1 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.770 |

| male | 145/272 (53.31) | 0.88 (0.56–1.40) | 1.09 (0.61–1.96) | ||

| country of birth | |||||

| other than Brazil | 3/21 (14.29) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Brazil | 199/352 (56.53) | 7.8 (2.26–26.98) | 10.74 (2.82–40.82) | ||

| countries of work in the last 3 yearsd | |||||

| FG and others | 47/115 (40.87) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.016 |

| FG only | 155/258 (60.08) | 2.18 (1.39–3.41) | 2 (1.14–3.55) | ||

| Attitude and knowledge | |||||

| malaria is a major health probleme | |||||

| no | 19/55 (34.55) | 1 | 0.001 | ||

| yes | 183/318 (57.55) | 2.57 (1.41–4.67) | |||

| better to treat even if test negativef | |||||

| no | 133/263 (50.57) | 1 | 0.031 | 1 | 0.039 |

| yes | 69/110 (62.73) | 1.64 (1.04–2.59) | 1.82 (1.03–3.22) | ||

| malaria stays all lifeg | |||||

| no | 148/287 (51.57) | 1 | 0.065 | ||

| yes | 54/86 (62.79) | 1.58 (0.97–2.60) | |||

| cure without treatmenth | |||||

| no | 180/342 (52.63) | 1 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.036 |

| yes | 22/31 (70.97) | 2.2 (0.98–4.92) | 3.19 (1.08–9.46) | ||

| protection against mosquitoes | |||||

| sometimes/never | 177/315 (56.19) | 1 | 0.066 | ||

| always/often | 25/58 (43.10) | 0.59 (0.34–1.04) | |||

| Clinical data | |||||

| past history of malaria | |||||

| ≤3 malaria attacks | 30/91 (32.97) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.005 |

| ≥4 malaria attacks | 172/282 (60.99) | 3.18 (1.93–5.23) | 2.47 (1.31–4.64) | ||

| date of last malaria attack | |||||

| ≤2 years | 130/194 (67.01) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.028 |

| >2 years | 72/179 (40.22) | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–1) | ||

| place when last malaria attack | |||||

| Brazil | 4/60 (6.67) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| FG | 188/274 (68.61) | 30.60 (10.75–87.11) | 22.1 (7.39–66.04) | <0.001 | |

| other | 10/39 (25.64) | 4.82 (1.39–16.74) | 6.11 (1.60–23.4) | 0.008 | |

| Plasmodium spp. PCR | |||||

| negative | 162/286 (56.64) | 1 | 0.081 | 1 | 0.002 |

| positive | 40/87 (45.98) | 0.65 (0.40–1.05) | 0.37 (0.20–0.68) | ||

Hosmer–Lemeshow test: P = 0.507.

Obtained from the likelihood ratio test.

Age and sex were forced.

Countries where people worked for gold mining in the last 3 years.

Considering malaria as a major health problem on mining sites.

Thinking that it is better to take a malaria treatment even if the malaria test is negative, just to be sure.

Thinking that malaria stays all life in the body.

Thinking that malaria can be cured without treatment.

Factors associated with poor adherence

Treatment adherence was statistically different between persons who got tested (n/N = 154/171, 90.1%) and those who self-medicated (n/N = 120/197, 60.9%) (P < 0.001). The main factors associated with poor adherence were self-medication (AOR = 6.03) and thinking that it is better to take a treatment even if the malaria test is negative (AOR = 2) (Table 2).

Factors associated with poor malaria treatment adherence in illegal gold miners working in FG, 2015 (n/N = 87/361)

| . | . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Poor adherence, n/N (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||

| sexc | ||||||

| female | 29/98 (29.59) | 1 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.184 | |

| male | 58/263 (22.05) | 0.67 (0.40–1.14) | 0.67 (0.37–1.21) | |||

| agec | ||||||

| ≤38 years | 52/172 (30.23) | 1 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.005 | |

| >38 years | 35/189 (18.52) | 0.52 (0.32–0.86) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |||

| work time in gold mining | ||||||

| ≤10 years | 56/202 (27.72) | 1 | 0.068 | |||

| >10 years | 31/159 (19.50) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | ||||

| Attitude and knowledge | ||||||

| better treat even if test negatived | ||||||

| no | 51/256 (19.92) | 1 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.016 | |

| yes | 36/105 (34.29) | 2.10 (1.26–3.48) | 2 (1.14–3.51) | |||

| malaria killse | ||||||

| no | 86/347 (24.78) | 1 | 0.089 | |||

| yes | 1/14 (7.14) | 0.23 (0.03–1.81) | ||||

| protection against mosquitos | ||||||

| sometimes/never | 78/304 (25.66) | 1 | 0.097 | |||

| always/often | 9/57 (15.79) | 0.54 (0.25–1.16) | ||||

| Clinical data | ||||||

| past history of malaria | ||||||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 16/89 (17.98) | 1 | 0.112 | |||

| ≥4 malaria attack | 71/272 (26.10) | 1.61 (0.88–2.95) | ||||

| date of last malaria attack | ||||||

| ≤2 years | 64/188 (34.04) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| >2 years | 23/173 (13.29) | 0.96 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | |||

| health-seeking behaviourf | ||||||

| get tested | 14/168 (8.33) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| self-medication | 73/193 (37.82) | 6.69 (3.60–12.43) | 6.03 (3.15–11.54) | |||

| place when last malaria attack | ||||||

| Brazil | 4/59 (6.78) | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| FG | 75/263 (28.52) | 5.48 (1.92–15.67) | ||||

| other | 8/39 (20.51) | 3.54 (0.99–12.74) | ||||

| . | . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Poor adherence, n/N (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||

| sexc | ||||||

| female | 29/98 (29.59) | 1 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.184 | |

| male | 58/263 (22.05) | 0.67 (0.40–1.14) | 0.67 (0.37–1.21) | |||

| agec | ||||||

| ≤38 years | 52/172 (30.23) | 1 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.005 | |

| >38 years | 35/189 (18.52) | 0.52 (0.32–0.86) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |||

| work time in gold mining | ||||||

| ≤10 years | 56/202 (27.72) | 1 | 0.068 | |||

| >10 years | 31/159 (19.50) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | ||||

| Attitude and knowledge | ||||||

| better treat even if test negatived | ||||||

| no | 51/256 (19.92) | 1 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.016 | |

| yes | 36/105 (34.29) | 2.10 (1.26–3.48) | 2 (1.14–3.51) | |||

| malaria killse | ||||||

| no | 86/347 (24.78) | 1 | 0.089 | |||

| yes | 1/14 (7.14) | 0.23 (0.03–1.81) | ||||

| protection against mosquitos | ||||||

| sometimes/never | 78/304 (25.66) | 1 | 0.097 | |||

| always/often | 9/57 (15.79) | 0.54 (0.25–1.16) | ||||

| Clinical data | ||||||

| past history of malaria | ||||||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 16/89 (17.98) | 1 | 0.112 | |||

| ≥4 malaria attack | 71/272 (26.10) | 1.61 (0.88–2.95) | ||||

| date of last malaria attack | ||||||

| ≤2 years | 64/188 (34.04) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| >2 years | 23/173 (13.29) | 0.96 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | |||

| health-seeking behaviourf | ||||||

| get tested | 14/168 (8.33) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| self-medication | 73/193 (37.82) | 6.69 (3.60–12.43) | 6.03 (3.15–11.54) | |||

| place when last malaria attack | ||||||

| Brazil | 4/59 (6.78) | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| FG | 75/263 (28.52) | 5.48 (1.92–15.67) | ||||

| other | 8/39 (20.51) | 3.54 (0.99–12.74) | ||||

Hosmer–Lemeshow test: P = 0.799.

Obtained from the likelihood ratio test.

Age and sex were forced.

Thinking that it is better to take a malaria treatment even if the malaria test is negative, just to be sure.

Thinking that malaria can kill.

For the last malaria attack.

Factors associated with poor malaria treatment adherence in illegal gold miners working in FG, 2015 (n/N = 87/361)

| . | . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Poor adherence, n/N (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||

| sexc | ||||||

| female | 29/98 (29.59) | 1 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.184 | |

| male | 58/263 (22.05) | 0.67 (0.40–1.14) | 0.67 (0.37–1.21) | |||

| agec | ||||||

| ≤38 years | 52/172 (30.23) | 1 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.005 | |

| >38 years | 35/189 (18.52) | 0.52 (0.32–0.86) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |||

| work time in gold mining | ||||||

| ≤10 years | 56/202 (27.72) | 1 | 0.068 | |||

| >10 years | 31/159 (19.50) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | ||||

| Attitude and knowledge | ||||||

| better treat even if test negatived | ||||||

| no | 51/256 (19.92) | 1 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.016 | |

| yes | 36/105 (34.29) | 2.10 (1.26–3.48) | 2 (1.14–3.51) | |||

| malaria killse | ||||||

| no | 86/347 (24.78) | 1 | 0.089 | |||

| yes | 1/14 (7.14) | 0.23 (0.03–1.81) | ||||

| protection against mosquitos | ||||||

| sometimes/never | 78/304 (25.66) | 1 | 0.097 | |||

| always/often | 9/57 (15.79) | 0.54 (0.25–1.16) | ||||

| Clinical data | ||||||

| past history of malaria | ||||||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 16/89 (17.98) | 1 | 0.112 | |||

| ≥4 malaria attack | 71/272 (26.10) | 1.61 (0.88–2.95) | ||||

| date of last malaria attack | ||||||

| ≤2 years | 64/188 (34.04) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| >2 years | 23/173 (13.29) | 0.96 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | |||

| health-seeking behaviourf | ||||||

| get tested | 14/168 (8.33) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| self-medication | 73/193 (37.82) | 6.69 (3.60–12.43) | 6.03 (3.15–11.54) | |||

| place when last malaria attack | ||||||

| Brazil | 4/59 (6.78) | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| FG | 75/263 (28.52) | 5.48 (1.92–15.67) | ||||

| other | 8/39 (20.51) | 3.54 (0.99–12.74) | ||||

| . | . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysisa . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Poor adherence, n/N (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | Pb . | AOR (95% CI) . | Pb . | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||

| sexc | ||||||

| female | 29/98 (29.59) | 1 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.184 | |

| male | 58/263 (22.05) | 0.67 (0.40–1.14) | 0.67 (0.37–1.21) | |||

| agec | ||||||

| ≤38 years | 52/172 (30.23) | 1 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.005 | |

| >38 years | 35/189 (18.52) | 0.52 (0.32–0.86) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |||

| work time in gold mining | ||||||

| ≤10 years | 56/202 (27.72) | 1 | 0.068 | |||

| >10 years | 31/159 (19.50) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | ||||

| Attitude and knowledge | ||||||

| better treat even if test negatived | ||||||

| no | 51/256 (19.92) | 1 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.016 | |

| yes | 36/105 (34.29) | 2.10 (1.26–3.48) | 2 (1.14–3.51) | |||

| malaria killse | ||||||

| no | 86/347 (24.78) | 1 | 0.089 | |||

| yes | 1/14 (7.14) | 0.23 (0.03–1.81) | ||||

| protection against mosquitos | ||||||

| sometimes/never | 78/304 (25.66) | 1 | 0.097 | |||

| always/often | 9/57 (15.79) | 0.54 (0.25–1.16) | ||||

| Clinical data | ||||||

| past history of malaria | ||||||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 16/89 (17.98) | 1 | 0.112 | |||

| ≥4 malaria attack | 71/272 (26.10) | 1.61 (0.88–2.95) | ||||

| date of last malaria attack | ||||||

| ≤2 years | 64/188 (34.04) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| >2 years | 23/173 (13.29) | 0.96 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | |||

| health-seeking behaviourf | ||||||

| get tested | 14/168 (8.33) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| self-medication | 73/193 (37.82) | 6.69 (3.60–12.43) | 6.03 (3.15–11.54) | |||

| place when last malaria attack | ||||||

| Brazil | 4/59 (6.78) | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| FG | 75/263 (28.52) | 5.48 (1.92–15.67) | ||||

| other | 8/39 (20.51) | 3.54 (0.99–12.74) | ||||

Hosmer–Lemeshow test: P = 0.799.

Obtained from the likelihood ratio test.

Age and sex were forced.

Thinking that it is better to take a malaria treatment even if the malaria test is negative, just to be sure.

Thinking that malaria can kill.

For the last malaria attack.

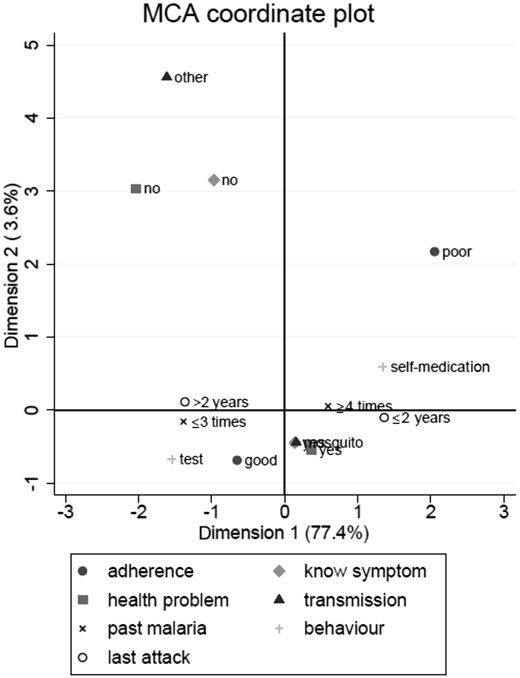

MCA

Two-dimensional projection of the correspondence analysis showed malaria behaviours on the first axis, with the opposition between self-medication and malaria testing. The second axis describes malaria knowledge with on the positive coordinate inadequate malaria knowledge. Dimension 1 plus 2 displayed 81% of the variance. The smaller the distance between points, the stronger was their association. Thus, self-medication, poor adherence, more than four malaria attacks, and the last malaria attack in the past 2 years were associated, as well as the opposite modalities (Figure 2).

Illegal gold miner behaviours towards malaria in FG, analysed with MCA.

Based on significant variables in the correspondence analysis, two clusters of people were defined with AHC. The first one regrouped people declaring a past history of three or less malaria attacks, the last one occurring more than 2 years ago, for which they got tested and were treated with a good adherence. They did not consider malaria as a major health problem. The second opposite cluster regrouped people declaring four or more malaria attacks, the last one more recently (less than 2 years ago), for which they self-medicated with a poor adherence. They considered malaria as a major health problem. Sociodemographic data did not differ between the two clusters (Table 3).

Two clusters of people in AHC (n = 361; =120 + 73 + 154 + 14)

| . | Cluster 1, N=213, n (%) . | Cluster 2, N=148, n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables included in ACH | |||

| health-seeking behaviour | |||

| get tested | 161 (75.6) | 7 (4.7) | |

| self-medication | 52 (24.4) | 141 (95.3) | <0.001 |

| treatment adherence | |||

| good | 206 (96.7) | 68 (45.9) | |

| poor | 7 (3.3) | 80 (54.1) | <0.001 |

| date of last malaria attack | |||

| ≤2 years | 56 (26.3) | 132 (89.2) | |

| >2 years | 157 (73.7) | 16 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| malaria is a major health problem | |||

| no | 44 (20.7) | 11 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| yes | 169 (79.3) | 137 (92.6) | |

| transmission pathway | |||

| other | 21 (9.9) | 11 (7.4) | |

| mosquito | 192 (90.1) | 137 (92.6) | 0.425 |

| past history of malaria | |||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 67 (31.5) | 22 (14.9) | |

| ≥4 malaria attack | 146 (68.5) | 126 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| symptoms knowledge | |||

| no | 28 (13.2) | 17 (11.5) | |

| yes | 185 (86.8) | 131 (88.5) | 0.639 |

| Socio-demographical data | |||

| sex | |||

| female | 50 (23.5) | 48 (32.4) | |

| male | 163 (76.5) | 100 (67.6) | 0.059 |

| age | |||

| ≤38 years | 96 (45.1) | 76 (51.4) | |

| >38 years | 117 (54.9) | 72 (48.6) | 0.239 |

| education | |||

| none/primary | 113 (53.1) | 69 (46.6) | |

| secondary/university | 100 (46.9) | 79 (53.4) | 0.229 |

| time in gold mining | |||

| ≤10 years | 112 (52.6) | 90 (60.8) | |

| >10 years | 101 (47.4) | 58 (39.2) | 0.121 |

| . | Cluster 1, N=213, n (%) . | Cluster 2, N=148, n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables included in ACH | |||

| health-seeking behaviour | |||

| get tested | 161 (75.6) | 7 (4.7) | |

| self-medication | 52 (24.4) | 141 (95.3) | <0.001 |

| treatment adherence | |||

| good | 206 (96.7) | 68 (45.9) | |

| poor | 7 (3.3) | 80 (54.1) | <0.001 |

| date of last malaria attack | |||

| ≤2 years | 56 (26.3) | 132 (89.2) | |

| >2 years | 157 (73.7) | 16 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| malaria is a major health problem | |||

| no | 44 (20.7) | 11 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| yes | 169 (79.3) | 137 (92.6) | |

| transmission pathway | |||

| other | 21 (9.9) | 11 (7.4) | |

| mosquito | 192 (90.1) | 137 (92.6) | 0.425 |

| past history of malaria | |||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 67 (31.5) | 22 (14.9) | |

| ≥4 malaria attack | 146 (68.5) | 126 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| symptoms knowledge | |||

| no | 28 (13.2) | 17 (11.5) | |

| yes | 185 (86.8) | 131 (88.5) | 0.639 |

| Socio-demographical data | |||

| sex | |||

| female | 50 (23.5) | 48 (32.4) | |

| male | 163 (76.5) | 100 (67.6) | 0.059 |

| age | |||

| ≤38 years | 96 (45.1) | 76 (51.4) | |

| >38 years | 117 (54.9) | 72 (48.6) | 0.239 |

| education | |||

| none/primary | 113 (53.1) | 69 (46.6) | |

| secondary/university | 100 (46.9) | 79 (53.4) | 0.229 |

| time in gold mining | |||

| ≤10 years | 112 (52.6) | 90 (60.8) | |

| >10 years | 101 (47.4) | 58 (39.2) | 0.121 |

Two clusters of people in AHC (n = 361; =120 + 73 + 154 + 14)

| . | Cluster 1, N=213, n (%) . | Cluster 2, N=148, n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables included in ACH | |||

| health-seeking behaviour | |||

| get tested | 161 (75.6) | 7 (4.7) | |

| self-medication | 52 (24.4) | 141 (95.3) | <0.001 |

| treatment adherence | |||

| good | 206 (96.7) | 68 (45.9) | |

| poor | 7 (3.3) | 80 (54.1) | <0.001 |

| date of last malaria attack | |||

| ≤2 years | 56 (26.3) | 132 (89.2) | |

| >2 years | 157 (73.7) | 16 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| malaria is a major health problem | |||

| no | 44 (20.7) | 11 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| yes | 169 (79.3) | 137 (92.6) | |

| transmission pathway | |||

| other | 21 (9.9) | 11 (7.4) | |

| mosquito | 192 (90.1) | 137 (92.6) | 0.425 |

| past history of malaria | |||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 67 (31.5) | 22 (14.9) | |

| ≥4 malaria attack | 146 (68.5) | 126 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| symptoms knowledge | |||

| no | 28 (13.2) | 17 (11.5) | |

| yes | 185 (86.8) | 131 (88.5) | 0.639 |

| Socio-demographical data | |||

| sex | |||

| female | 50 (23.5) | 48 (32.4) | |

| male | 163 (76.5) | 100 (67.6) | 0.059 |

| age | |||

| ≤38 years | 96 (45.1) | 76 (51.4) | |

| >38 years | 117 (54.9) | 72 (48.6) | 0.239 |

| education | |||

| none/primary | 113 (53.1) | 69 (46.6) | |

| secondary/university | 100 (46.9) | 79 (53.4) | 0.229 |

| time in gold mining | |||

| ≤10 years | 112 (52.6) | 90 (60.8) | |

| >10 years | 101 (47.4) | 58 (39.2) | 0.121 |

| . | Cluster 1, N=213, n (%) . | Cluster 2, N=148, n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables included in ACH | |||

| health-seeking behaviour | |||

| get tested | 161 (75.6) | 7 (4.7) | |

| self-medication | 52 (24.4) | 141 (95.3) | <0.001 |

| treatment adherence | |||

| good | 206 (96.7) | 68 (45.9) | |

| poor | 7 (3.3) | 80 (54.1) | <0.001 |

| date of last malaria attack | |||

| ≤2 years | 56 (26.3) | 132 (89.2) | |

| >2 years | 157 (73.7) | 16 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| malaria is a major health problem | |||

| no | 44 (20.7) | 11 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| yes | 169 (79.3) | 137 (92.6) | |

| transmission pathway | |||

| other | 21 (9.9) | 11 (7.4) | |

| mosquito | 192 (90.1) | 137 (92.6) | 0.425 |

| past history of malaria | |||

| ≤3 malaria attack | 67 (31.5) | 22 (14.9) | |

| ≥4 malaria attack | 146 (68.5) | 126 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| symptoms knowledge | |||

| no | 28 (13.2) | 17 (11.5) | |

| yes | 185 (86.8) | 131 (88.5) | 0.639 |

| Socio-demographical data | |||

| sex | |||

| female | 50 (23.5) | 48 (32.4) | |

| male | 163 (76.5) | 100 (67.6) | 0.059 |

| age | |||

| ≤38 years | 96 (45.1) | 76 (51.4) | |

| >38 years | 117 (54.9) | 72 (48.6) | 0.239 |

| education | |||

| none/primary | 113 (53.1) | 69 (46.6) | |

| secondary/university | 100 (46.9) | 79 (53.4) | 0.229 |

| time in gold mining | |||

| ≤10 years | 112 (52.6) | 90 (60.8) | |

| >10 years | 101 (47.4) | 58 (39.2) | 0.121 |

State of parasite susceptibility to artemisinin derivatives in FG

Among the 421 miners included, 94 were diagnosed positive by PCR for Plasmodium spp. carriage including 55 P. falciparum cases (10 coinfected with Plasmodium vivax). The other PCR were positive for P. vivax only (35/94), Plasmodium malariae (3/94) and P. vivax and P. malariae (1/94). Among these P. falciparum samples, the parasite density was sufficient for successful amplification and sequencing of the pfK13 gene in 32 samples (58%). None of them revealed any mutation in the propeller part of the gene.

Six P. falciparum samples were successfully phenotyped using the RSA method. Five out of six exhibited a 0% survival rate. The last one exhibited a survival rate of 2.70%, which is above the decreased sensitivity threshold of 1%. This result has not been confirmed by a second analysis (survival rate at 0%). However, this isolate was also associated with an in vitro susceptibility (IC50) to artemether of 14.18 nM, whereas the other values were between 1.35 and 5.42 nM. This value is considered to be higher than the decreased susceptibility threshold of 12 nM. Therefore, those two methods suggest at least a transient resistance profile for these parasites to artemisinin derivatives. These parasites were isolated from a 28-year-old Brazilian man who took one pill of Artecom® 4 days before the sampling for malaria symptoms.

Discussion

Study limitations

Because sampling did not use probabilistic methods, we cannot exclude recruitment biases. Behaviour in case of malaria symptoms and adherence were analysed with a questionnaire, which may lead to declaration bias (‘correct answer’ given to health professional) and memory bias. Missing data (eight for adherence for example) could also contribute to bias the results.

Frequent self-medication linked to difficult access to care in FG

This study showed that self-medication is very common in illegal gold miners working in FG: 53.7% resorted to self-medication for the last malaria episode. These results confirm previous observations in a specific mining site in FG.7

The multivariate analysis shows that health-seeking behaviour depends on which country gold miners worked in: being in FG during the last malaria attack was the main factor associated with self-medication. This suggests that access to malaria diagnosis in FG is particularly difficult for Brazilian gold miners compared with Brazil or Suriname. The main reason given by gold miners was the remoteness of the mine from the healthcare centres (93.4% versus 64% in the Surinamese survey) and we could also add the illegality of their activities and residency in France. Currently, in Suriname, MSD procure free malaria diagnostic tests and treatment everywhere on the Surinamese territory, even in gold mining areas, with the programme ‘Looking for Gold, Finding Malaria’.3,21 In Suriname, 50% of gold miners declared having used self-medication during the past 18 months in 2013, but these results included people working in Suriname and in FG, without differentiation. Therefore, it was not representative of the specific behaviour of gold miners in Suriname.8 Thus, even if healthcare is free for everyone in FG, in practice it is difficult to reach these healthcare structures for illegal gold miners who often live days away.

Self-medication was also linked to personal malaria history: the more people had experienced malaria, the more they were likely to self-treat themselves. This link could also be explained by a general behaviour which associates: disregarding health issues, not protecting themselves from malaria and not seeking medical care. We could assume that the acquired knowledge about treatment after the first malaria attack could facilitate self-medication for future malaria episodes. Malaria treatment misconceptions were also associated with self-medication. This emphasizes the necessity to reinforce public health messages for this specific population.

Self-medication is quasi-exclusively associated with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) intake

The majority of the drugs used in self-medication are ACTs (90%). This is concordant with what was observed in Suriname (96.1%).8 Treatment was mainly Artecom®, produced by a Chinese firm, Tonghe Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Chongqing, China). This drug had good efficacy and tolerance in Africa and Asia.22,23 However, Artecom® has some weaknesses: the dihydroartemisinin dose may vary; and there is no information on the dose of primaquine included in the box.24,25 The information leaflet in a package of Artecom® bought in the forest during the study mentioned the regimen in English and French (two pills twice a day for 2 days), which is not understandable for most Brazilian miners. Finally, the package indicated ‘protect from light and keep in a dry and cool place’, which is probably not feasible in illegal gold mining sites in the Amazonian forest.

Malaria treatment adherence is better when it is cheap and delivered by health workers

It is difficult to really evaluate adherence, generally based on self-reports or pill counts.26,27 In this study, the question ‘did pills remain when you have stopped the treatment?’ was used to allow comparison with the results from the Surinamese anthropological study8 and because the packaging of drugs used in our region (in legal or illegal market) contains one complete treatment. A Brazilian study in the Amazon basin found a difference between self-reported non-adherence and pill counts (12.2% versus 21.8%).28 But in Tanzania, the comparison of declared adherence with adherence estimated through ‘smart blister packs’ (Coartem® tablets with a microchip recording pills push out date and time) showed very similar results (64% of complete adherence versus 67%).29 Studies assessing adherence refer to a current malaria attack. But in this study, the behaviour concerned the last malaria attack, which occurred at a median of 2 years before. When the last malaria attack occurred long before, people were more likely to have declared getting tested and having taken the complete malaria treatment. This may reflect a memory bias, leading to the embellishment of reality towards the socially desirable answer. So malaria diagnosis and treatment adherence might have been overestimated. Self-medication and poor adherence could therefore be even more frequent than reported.30

Treatment adherence was significantly better when the treatment was given after getting a malaria test (90.1% versus 60.9% if self-medication). This suggests that there was a real impact of getting tested and having malaria treatment with explanations from health workers. In the Surinamese study, the same results were found with 78.9% of the miners who declared having completed the treatment when given by a health worker compared with 40.2% when self-medicated.8 In 2015, a meta-analysis observed worldwide a higher level of adherence to ACT in the public sector than in the retail sector (76% versus 45%).26 This could be explained by the fact that, in the public sector, ACTs are given for free with instructions by the health workers, whereas informal drug stores dispense a presumptive malaria treatment without clear instructions. A study in Uganda in 2016 reinforced this idea as it found no association between testing and treatment adherence as long as the treatment sent by shop vendors was associated with treatment information.31 Besides the lack of treatment information, the high cost of the treatment on the black market is another factor leading to poor adherence. In fact, ACTs cost 1 – 3 g of gold (30–90 USD). Therefore, most people declared interrupting the treatment as soon as they felt better, and kept pills for the next malaria episode. Thus, the easy availability (for free or at a low price) and explanation from health workers might explain the association between malaria test and adherence.

Putative emergence of artemisinin resistance in the parasite population of FG

This high level of self-medication raises the concern of selection for drug-resistant parasites. In Guyana (formerly English Guiana), 5% of the isolates collected in 2010 carried the C580Y pfK13 mutation.32 Since then, no other mutations associated with artemisinin resistance in South-East Asia have been observed on the Guiana Shield.33 Phenotyping methods identified one putative resistant isolate with a survival rate above the threshold. However, this result was not confirmed despite the conformity of the quality control (Cambodian strains). We could speculate that these parasites exhibited a transient stage of resistance/tolerance that is not stable through time and not necessarily associated with mutations on the pfK13 gene. This phenotype could have been lost during in vitro multiplication.34 Therefore, resistance parameters to characterize parasite resistance to artemisinin in South America still need to be validated.

Whether artemisinin resistance has already emerged or not, there is an urgent need for actions

Malaria resistance is a threat to health worldwide.35 The risk factors for selection of resistance are well known and this study showed that they are present in FG with people who self-medicated with poor adherence. In addition, the quality of the drug could be altered by living conditions and poor storage conditions. Parasite phenotyping suggested that the first step of resistance selection was reached with some parasites exhibiting transient stage on the path of resistance.

Therefore, it is urgent to address the problem based on the data provided by the scientific evidence (the present study as well as Douine et al.,6 Pommier de Santi et al.7 and Heemskerk and Duijves8). To limit self-medication and poor adherence, improving the access to diagnosis, and free, or even cheap, medication delivered with instructions for use are required. Countering false beliefs is also required: one-third of interviewed people thought that it was better to take a treatment even if the malaria test was negative and 6.4% used ACT as chemoprophylaxis. Besides treatment improvement, individual protection from vectors in these areas of high transmission is crucial and the distribution of insecticide-treated nets should be improved. Gold miners are easily accessible on resting sites and are concerned about their health. Public health interventions in cooperation with Suriname and Brazil should be considered to reduce malaria transmission and limit the risk of emergence of artemisinin resistance, which would have disastrous health and economic consequences well beyond FG.35

Acknowledgements

We thank Claude Flamand, Maria do Rosário O. Martins and Claire Cropet for helpful discussions about statistical analyses.

Funding

This study was funded by European Funds for Regional Development (Feder), N° Presage 32078, benefited from funding from Santé Publique France (French Ministry of Health) and was supported by an ‘Investissement d'Avenir’ grant managed by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (CEBA, ref. ANR-10-LABX-25–01). The funding bodies had no role in the study or the publication process.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.