Novel Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives as Potential Antimalarial Agents through Receptor–Inhibitor Interaction Fingerprint and Biosynthesis Design

Rosmalena1, Vivitri D. Prasasty2 and Muhammad Hanafi3

1Department of Medical Chemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

2Faculty of Biotechnology, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

3Research Center for Chemistry, Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Puspiptek, Serpong, Indonesia.

Corresponding Author E-mail: hanafi124@yahoo.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/ojc/340556

Article Received on : 18-01-2018

Article Accepted on : 25-08-2018

Article Published : 06 Oct 2018

Malaria parasites have become the major health threat in increasing resistance toward common antimalarial drugs and become prime factors causing the strength of the disease. The objective of this study was investigating novel cinchona alkaloid derivatives (CADs) as potential antimalarial agents through molecular docking, pharmacopore modeling and biosynthesis design. Protein structure and cinchona alkaloid derivative structures were taken and performed for molecular interaction studies, pharmacophore modeling and mapping the binding modes of receptor-inhibitors which may increase the possibility of success rate in finding potential antimalarial candidates. Here, we report the greatest prospective inhibitor of Pf falcipain-2 is cinchonidine salicylate (-9.1 kcal/mol) through molecular docking approach. This compound exhibited distortion free of Lipinski`s rule. Hence, cinchonidine salicylate showed the most potential compound as antimalarial inhibitor over other cinchona alkaloid derivatives. Eventually, we construct biosynthesis pathways by using iron oxide nanoparticle (IONP) that could act as a coated nanoparticle to the natural bioactives to acquire optimum yield of the product by making coated nanoparticle with CADs which are powerful biosynthesis application in green environment of aqueous solution.

KEYWORDS:Antimalaria; Biosynthesis; Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives; Molecular Docking

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Rosmalena R, Prasasty V. D, Hanafi M. Novel Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives as Potential Antimalarial Agents through Receptor–Inhibitor Interaction Fingerprint and Biosynthesis Design. Orient J Chem 2018;34(5). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Rosmalena R, Prasasty V. D, Hanafi M. Novel Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives as Potential Antimalarial Agents through Receptor–Inhibitor Interaction Fingerprint and Biosynthesis Design. Orient J Chem 2018;34(5). Available from: http://www.orientjchem.org/?p=50334 |

Introduction

Malaria is an endemic disease caused by parasitic infection which influencing over than 224 million people and effecting mortality approximately 700,000 every year in the world.1 According to 41% of total world’s population, malaria is spreading in some areas of Africa, Asia, America, Hispaniola, and Oceania,2-4 where Africa is the highest malarial prevalent area of the world annually.5-7 Malaria is known as a vector born disease transmitted by female Anopheles mosquito and parasitic infection mostly caused by five species, including Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium knowlesi.8

There are three families of drugs currently used for eradicating malaria disease, such as antifolates (pyrimethamine, sulfadoxine), quinolones (chloroquine, primaquine, quinine, mefloquine) and artemisinin derivatives. However, these drugs have limitation due to high cost and high resistance rate to malaria endemic causing frequent chemotherapy failure.9-12 Understanding the resistance mechanisms could enhance new therapies.13-15 Thus, drug resistances are becoming key concerns in eradicating malaria. Various promising antimalarial agents have already been developed. Unfortunately, only few promising antimalarial agents contribute sufficient efficacy and small effect toxicity for antimalarial therapies.16-18 Therefore, several attempts have been started to identify clinical targets for healing human malarial disease. Molecular modeling19-22 and database formation approaches as new techniques are currently in the innovation development and execution stages23-26 to enhance potential antimalarial targets.27-31

In this work, we brought out quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) analysis of cinchona alkaloid derivatives as falcipain-2 inhibitors using molecular docking and pharmacophore analysis methods. Moreover, we explored the prime interactions of intermolecular between cinchona alkaloid derivatives and Pf falcipain-2 utilizing molecular docking approach and used this datasets to improve rational drug design methods. Thus, simultaneous QSAR and virtual screening through docking could give benefits to understand the structure–activity relationships of falcipain-2 inhibitors and the design of new potent malarial inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Crystallographic Protein Structure

The crystallographic structure of falcipain-2 protein of Plasmodium falciparum (Pf falcipain-2, PDB ID code 2ghu) was retrieved from Protein Database (PDB). The removal of ligand binding and all crystallographic water molecules of falcipain-2 structure were done. The final falcipain-2 structure was saved in pdb format for further in silico analysis.

Preparation of CAD Datasets

Cinchona alkaloid derivative 3D structures were generated by ChemDraw Ultra 12.032, 33 and saved in pdb formats. The atomic spatial arrangement energies of all the 46 CADs were minimized by using MMFF94 force field. The 46 molecules of CADs were designed by subtituting –R group positions of CADs on the side chains. The structures were calculated based on physicochemical properties using Chemicalize (ChemAxon)34 and Molsoft35 platforms. These physicochemical properties are important for evaluating drug candidate in drug discovery from initial design to in vitro and in vivo studies.

The drug-like pProperties Analysis of CADs

Molsoft Drug – Likeness Platform were used in analyzing physicochemical properties of all the 46 CADs 3D structures. The physicochemical properties were identified including molecular weight, Log P, hydrogen bond donor (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptor, and total polar surface of CADs compounds were studied. The drug-likeness were evaluated following Lipinski’s rule of five.

Molecular Docking Analysis of Pf Falcipain-2 and CADs

All the 46 CAD compounds were docked into Pf falcipain-2 protein using Autodock Vina program (Vina, The Scripps Institute). The partial charges of the ligands and the polar hydrogens in the protein were set, separately using the Gasteiger method in AutoDock tools (ADT). The flexibility of ligand torsion angles were assigned at all rotatable bonds and the protein structure was prepared as rigid form. protein is prepared as a rigid structure. Protein and ligands were saved as pdbqt format and ready for docking analysis. The expected binding energy values should be the lowest value which indicated the most favorable binding interaction between protein and ligand.

Results

In order to investigate the antimalaria potency of cinchona alkaloid derivatives, crystallographic structure of falcipain-2 protein of Plasmodium falciparum was obtained and the structure was refined by removing bound-ligand and all crystallographic water structures. The standalone structure of receptor-inhibitors were focused on molecular docking analysis using Autodock Vina. This docking program is a well-known practical function to use algorithm which is according to steered stochastic parallel direct search evolution strategy optimization method that is adequately rapid and moderately robust, which is known using an algorithm that incorporates the optimization of distinctive evolution technique and binding pocket prediction. The automated binding pocket prediction in conjunction with self-activating protein and ligand preparation fully executes overall measurement process.

From all the 46 CADs tested, the variation of R-substitutions gave different molecular weights ranging from 294.17 to 450.29 (Table 1). The molecular interactions found in molecular docking analysis were shown by the presence of cinchona alkaloid derivatives in various affinity energies interacting with Pf Falcipain-2 (Table 2). It showed the best inhibition activity in terms of affinity energy is cinchonidine salicylate (-9.1 kcal/mol). All CADs also showed followed Lipinski`s law and only 4 out of 46 that have 1 violation. According to the lowest affinity energy values of all CADs, only Cinchonidine salicylate was selected for further bioactivity analyses among others.

Table 1: The designed cinchona alkaloid derivatives and parental cinchona compound.

| No. | Compound Name | Substitution of –R group | Molecular Weight |

| 1 | Quinine (Q) | HO- | 324 |

| 2 | Q-butanoate | CH3CH2CH2 OC(O)- | 364 |

| 3 | Q-isobutanoate | (CH3)2CH-OC(O)- | 394 |

| 4 | Q-isovalerate | (CH3)2CHCH2OC(O)- | 408 |

| 5 | Q-tiglate | (CH3)(CHCH2)OC(O)C- | 406 |

| 6 | Quinidine (Qd) | HO- | 326 |

| 7 | Qd-butanoate | CH3CH2 CH2(O)CO- | 394 |

| 8 | Qd-isovalerate | (CH3)2CH(O)CO- | 408 |

| 9 | Qd-tiglate | (CH3)2 CHCH2(O)CO- | 406 |

| 10 | Cinchonidine (C) | HO- | 294 |

| 11 | C-butanoate | CH3CH2CH2(O)CO- | 364 |

| 12 | C-isobutanoate | (CH3)2CH(O)CO- | 364 |

| 13 | C-isovalerate | (CH3)(CH2CH)C(O)CO- | 340 |

| 14 | C-tiglate | (CH3)2CHCH2(O)CO- | 376 |

| 15 | Cinchonine (Cn) | HO- | 337 |

| 16 | Cn-butanoate | CH3CH2CH2(O)CO- | 364 |

| 17 | Cn-isovalerate | (CH3)2CH(O)CO- | 357 |

| 18 | Cn-tiglate | (CH3)2CHCH2(O)CO- | 376 |

| 19 | Hexyl-Q- ether | H13C6O- | 408 |

| 20 | Hexyl-Qd-ether | H13C6O- | 408 |

| 21 | Hexyl-C-ether | H13C6O- | 378 |

| 22 | Hexyl-Cn-ether | H13C6O- | 378 |

| 23 | Isopropyl-Q-ether | (CH3)2HCO- | 366 |

| 24 | Isopropyl-Qd-ether | (CH3)2HCO- | 366 |

| 25 | Isopropyl-Cn-ether | (CH3)2HCO- | 336 |

| 26 | Isopropyl-C-ether | (CH3)2HCO- | 336 |

| 27 | Buthyl quinine ether | -OC4H9 | 380 |

| 28 | Buthyl quinidine ether | -OC4H9 | 380 |

| 29 | Buthyl cinchonine ether | -OC4H9 | 350 |

| 30 | Buthyl cinchonidine ether | -OC4H9 | 350 |

| 31 | Cinchonidine 4-hydroxybenzoate | -O3C7H5 | 414 |

| 32 | Cinchonidine octanoate | -OC8H15 | 420 |

| 33 | Cinchonidine salicylate | -O3C7H5 | 414 |

| 34 | Cinchonidine succinate | -O4C4H4 | 394 |

| 35 | Cinchonine octanoate | -O3C7H5 | 414 |

| 36 | Cinchonine salicylate | -OC8H15 | 420 |

| 37 | Cinchonine succinate | -O3C7H5 | 414 |

| 38 | Cinchonine 4-hydroxybenzoate | -O4C4H4 | 394 |

| 39 | Quinidine 4-hydroxybenzoate | -O3C7H5 | 444 |

| 40 | Quinidine octanoate | -OC8H15 | 450 |

| 41 | Quinidine salicylate | -O3C7H5 | 444 |

| 42 | Quinidine succinate | -O4C4H4 | 424 |

| 43 | Quinine 4-hydroxybenzoate | -O3C7H5 | 430 |

| 44 | Quinine octanoate | -OC8H15 | 450 |

| 45 | Quinine salicylate | -O3C7H5 | 444 |

| 46 | Quinine succinate | -O4C4H4 | 414 |

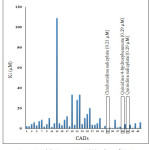

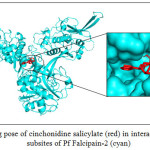

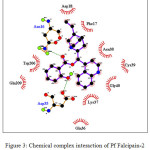

CADs have various inhibition activities, with inhibitor constant (Ki) values ranging from 0.2 to 109 µM. It indicates the potent of Pf falcipain-2 inhibitor which is a number of concentration required to produce half maximum inhibition, as depicted in Fig. 1. Molecular docking interaction between Pf falcipain-2 and cinchonidine salicylate is described in Fig. 2. The chemical interaction between cinchonidine salicylate and Pf falcipain-2 resulted nine hydrophobic interactions to stabilize the binding mode of cinchonidine salicylate in cavity site of Pf falcipain-2. Two hydrogen bonds also contributed in stabilizing complex interaction (Fig. 3).

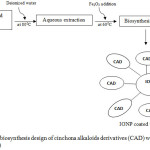

It has been known that physical and chemical nanomaterial synthesis procedures are either complicated, time consuming or expensive. Sometimes, the unwanted toxic chemicals could stay adsorbed to the surface of nanomaterials and ultimately prevent its wide range therapeutic applications.36-38 A mild, less costly, fast and simple method for the biosynthesis IONPs has been successfully exhibited at the first time by using aqueous leaf extracts of Sageretia thea.39 Biomimetic synthesis is more suitable due to it has no obstacle relative to the physical or chemical methods. Hence, biomimetic synthesis could be effectively used for biological applications. Here, we propose deionized water technique in aqueous extraction of CA natural resources and coating with iron oxide nanoparticle to produce IONP coated with CAD, as we describe on Fig. 4.

Discussion

Previous experiments targeting Pf falcipain-2 using two inhibitors, cystatin40 and chagasin41 have failed due to their poor pharmacological profiles besides being prone to degradation by host enzymes. Thus, we drive to investigate new potential antimalarial drugs from native plant sources of Indonesia. The compounds are mainly alkaloids and phenolics, which have antimalarial activities such as cinchona alkaloids.42-44 Some of these compounds have known biological activities. For instance, quinine, quininide, cinchonine and cinchonidine are identified as antiparasitic malaria converting enzyme inhibitors.45-47 Docking results showed that inhibition activities of CAD compounds exhibited poor to excellent binding affinities to targeted Pf falcipain-2 (Table 2). In most cases, most of these poor binders had a long carbon chain or an attached nucleus hence could not fit in the “ditch-like” binding pocket, the characteristic of the falcipains. These results increase our understanding of the structure-function of complex interactions. Thus, based on the binding energy and hydrogen bond interaction, it can be confirmed that cinchonidine salicylate is the best inhibitor to Pf falcipain-2.

Table 2 : Involved binding energy values and CADs properties.

| No. | Compound Name | Consensus Log P | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Violation of Lipinski`s Rule |

| 1 | Quinine (Q) | 2.41 | -7.7 | 0 |

| 2 | Q-butanoate | 3.76 | -7.7 | 0 |

| 3 | Q-isobutanoate | 3.59 | -7.3 | 0 |

| 4 | Q-isovalerate | 4.18 | -7.1 | 0 |

| 5 | Q-tiglate | 4.22 | -7.5 | 0 |

| 6 | Quinidine (Qd) | 1.96 | -7.0 | 0 |

| 7 | Qd-butanoate | 3.85 | -6.9 | 0 |

| 8 | Qd-isovalerate | 4.18 | -7.8 | 0 |

| 9 | Qd-tiglate | 4.22 | -7.3 | 0 |

| 10 | Cinchonidine (C) | 2.32 | -6.8 | 0 |

| 11 | C-butanoate | 3.76 | -7.9 | 0 |

| 12 | C-isobutanoate | 3.50 | -7.2 | 0 |

| 13 | C-isovalerate | 4.10 | -5.4 | 0 |

| 14 | C-tiglate | 4.13 | -7.2 | 0 |

| 15 | Cinchonine (Cn) | 2.41 | -7.5 | 0 |

| 16 | Cn-butanoate | 3.76 | -6.9 | 0 |

| 17 | Cn-isovalerate | 4.68 | -6.7 | 0 |

| 18 | Cn-tiglate | 4.13 | -7.7 | 0 |

| 19 | Hexyl-Q- ether | 5.27 | -6.1 | 1 |

| 20 | Hexyl-Qd-ether | 5.27 | -7.4 | 1 |

| 21 | Hexyl-C-ether | 5.18 | -6.2 | 1 |

| 22 | Hexyl-Cn-ether | 5.18 | -6.1 | 1 |

| 23 | Isopropyl-Q-ether | 3.66 | -7.3 | 0 |

| 24 | Isopropyl-Qd-ether | 3.66 | -6.8 | 0 |

| 25 | Isopropyl-Cn-ether | 3.57 | -6.6 | 0 |

| 26 | Isopropyl-C-ether | 3.57 | -6.4 | 0 |

| 27 | Buthyl quinine ether | 4.30 | -7.4 | 0 |

| 28 | Buthyl quinidine ether | 4.30 | -7.4 | 0 |

| 29 | Buthyl cinchonine ether | 4.21 | -7.2 | 0 |

| 30 | Buthyl cinchonidine ether | 4.21 | -6.8 | 0 |

| 31 | Cinchonidine 4-hydroxybenzoate | 4.20 | -8.6 | 0 |

| 32 | Cinchonidine octanoate | 5.69 | -7.6 | 0 |

| 33 | Cinchonidine salicylate | 4.08 | -9.1 | 0 |

| 34 | Cinchonidine succinate | 2.36 | -8.2 | 0 |

| 35 | Cinchonine octanoate | 4.20 | -8.6 | 0 |

| 36 | Cinchonine salicylate | 5.69 | -6.9 | 0 |

| 37 | Cinchonine succinate | 4.08 | -8.1 | 0 |

| 38 | Cinchonine 4-hydroxybenzoate | 2.36 | -7.8 | 0 |

| 39 | Quinidine 4-hydroxybenzoate | 4.29 | -8.8 | 0 |

| 40 | Quinidine octanoate | 5.78 | -7.3 | 0 |

| 41 | Quinidine salicylate | 4.17 | -8.9 | 0 |

| 42 | Quinidine succinate | 2.45 | -7.4 | 0 |

| 43 | Quinine 4-hydroxybenzoate | 3.94 | -8.3 | 0 |

| 44 | Quinine octanoate | 5.78 | -7.2 | 0 |

| 45 | Quinine salicylate | 4.17 | -8.4 | 0 |

| 46 | Quinine succinate | 2.16 | -7.1 | 0 |

|

Figure 1: Inhibition constant (Ki) values of CADs. |

|

Figure 2: Binding pose of cinchonidine salicylate (red) in interaction to the various subsites of Pf Falcipain-2 (cyan) |

|

Figure 3: Chemical complex interaction of Pf Falcipain-2 and cinchonidine salicylate. |

|

Figure 4: Schematic biosynthesis design of cinchona alkaloids derivatives (CAD) with iron oxide nanoparticle (IONP). |

Based on molecular docking result, cinchonidine salicylate is the best candidate as antimalaria from all the 46 constructed molecules of CADs. This dataset will be used as a candidate for molecule organic synthesis and bioactive validation into in-vivo and in-vitro experiments.

Furthermore, we propose the design of green synthesis of CAD which is non toxic and more effective through the interface of eco-friendly and nanomaterial technology application allows a great line to synthesize CADs, for instance cinchonidine salicylate with eco-friendly and safe all-around functional nanoparticles of metal oxide. Multifunctional iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) have arose as an expectant material for various applications, such as cosmeceutical, biomedicine, bioremediation and material engineering purposes.39 Surprisingly, IONPs utilization in biomedical field are in high demand and growth exponentially.48, 49 The capability of IONPs in the restraint detach of drugs including for tissue restoration, medical treatment and diagnostic has previously been proven50, 51 The wide range of IONP applications can be assigned by ideal properties such as high surface area, small band gap and stability. This proposed schematic biosynthesis with IONPs would be very beneficial in complete environmental friendly process utilizing the aqueous plant part extracts of CADs. The phytochemical resources is an effective reducing toxic effetcs as well as capping agent without adding any chemical reagents.

The development of protease inhibitors become a promising approach in antimalarial drug discovery, particularly in interfering organisms with capability in metabolizing human hemoglobin as main nutrient sources. A great relationship between the affinity energies for docked CAD compounds and their bound Ki values assured to be an acceptance for the protein target. Moreover, our study also presented the insight of the nature of ligands binding to the receptor. Pf falcipain-2 crystallographic structure serves a great feature to construct and develop novel antimalarial agents that could combat one of the major factors of unveiling conformation of hemoglobin. In contrast, the effective block of parasite growth by parasite suppression in hemoglobin hydrolysis needs a potent inhibition of Pf falcipain-2. In addition, the proposed cinchonidine salicylate could be used as structure-based drug design reference studies which supporting chemo-treatment development to eradicate malaria. In this study, cinchonidine salicylate is proposed for further lead synthesis by using pure iron oxide maghemite (Fe2O3) phase nanoparticles as an environment-friendly, uncomplicated, fast and powerful method through green chemistry ways to obtain high yield of CAD product in non-toxic aqueous solution.

Conclusion

One of the promising approaches in antimalarial drug discovery is the development of protease inhibitors for interfering malaria parasites ability to metabolize human hemoglobin as a source of nutrients. An excellent correlation between the interaction energies for various docked CAD compounds and their respective Ki values proven to be an endorsement for the protein target. In addition, these studies also provided insight into the nature of binding and interaction of ligands with the enzyme. Falcipain-2 crystallographic structure offers a promising opportunity to design and develop novel inhibitors that could block one of the major mediators of hemoglobin denaturation. However, effective blockade of parasite development by suppression of parasite hemoglobin hydrolysis would likely require a potent inhibition of falcipain-2. In any event, the proposed cinchonidine salicylate could be used to direct structure-based drug design studies leading to development of chemotherapeutic agents to eradicate malaria. In this study, cinchonidine salicylate is proposed for further lead synthesis by using pure iron oxide maghemite (Fe2O3) phase nanoparticles as an eco-friendly, economical, simple, rapid and robust method based on green chemistry approach, to obtain high yield of CAD product in non-toxic aqueous environment.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Scientific Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Chemistry, University of Indonesia for valuable support in this research.

References

- Bhaumik, S. Natl Med J India, 2013, 26, 62.

- Sutherland, C.J.; Hallett, R. J Infect Dis, 2009, 199, 1561-3.

CrossRef - Miguel-Oteo, M.; Jiram, A.I.; Ta-Tang, T.H.; Lanza, M.; Hisam, S.; Rubio, J.M. Asian Pac J Trop Med, 2017, 10, 299-304.

CrossRef - Mens, P.F.; Schoone, G.J.; Kager, P.A.; Schallig, H.D. Malar J, 2006, 5, 80.

CrossRef - Dandalo, L.C.; Brooke, B.D.; Munhenga, G.; Lobb, L.N.; Zikhali, J.; Ngxongo, S.P.; Zikhali, P.M.; Msimang, S.; Wood, O.R.; Mofokeng, M.; Misiani, E.; Chirwa, T.; Koekemoer, L.L. J Med Entomol, 2017.

- Sanchez-Mazas, A.; Cerny, V.; Di, D.; Buhler, S.; Podgorna, E.; Chevallier, E.; Brunet, L.; Weber, S.; Kervaire, B.; Testi, M.; Andreani, M.; Tiercy, J.M.; Villard, J.; Nunes, J.M. Mol Ecol, 2017.

- Brower, V. Lancet Infect Dis, 2017, 17, 1026-1027.

CrossRef - Antinori, S.; Galimberti, L.; Milazzo, L.; Corbellino, M. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 2012, 4, e2012013.

CrossRef - Alam, M.S.; Ley, B.; Nima, M.K.; Johora, F.T.; Hossain, M.E.; Thriemer, K.; Auburn, S. ;Marfurt, J.; Price, R.N.; Khan, W.A. Malar J, 2017, 16, 335.

CrossRef - Lohy Das, J.; Dondorp, A.M.; Nosten, F.; Phyo, A.P.; Hanpithakpong, W.; Ringwald, P.; Lim, P.; White, N.J.; Karlsson, M.O.; Bergstrand, M.; Tarning, J. AAPS J, 2017.

- Maslachah, L.; Widiyatno, T.V.; Yustinasari, L.R.; Plumeriastuti, H. Vet World, 2017, 10, 790-797.

CrossRef - Saksena, R.; Matlani, M.; Singh, V.; Kumar, A. ;Anveshi, A.; Kumar, D.; Gaind, R. Int Med Case Rep J, 2017, 10, 289-294.

CrossRef - Antonio-Nkondjio, C.; Sonhafouo-Chiana, N.; Ngadjeu, C.S.; Doumbe-Belisse, P.; Talipouo, A.; Djamouko-Djonkam, L.; Kopya, E.; Bamou, R.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Wondji, C.S. Parasit Vectors, 2017, 10, 472.

CrossRef - Liu, B.Q.; Qiao, L.; He, Q.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, S.; Chen, B. Insect Sci, 2017.

- Salgueiro, P.; Lopes, A.S.; Mendes, C.; Charlwood, J.D.; Arez, A.P.; Pinto, J.; Silveira, H. Parasit Vectors, 2016, 9, 515.

CrossRef - Miller, L.H.; Ackerman, H.C.; Su, X.Z.; Wellems, T.E. Nat Med, 2013, 19, 156-67.

CrossRef - Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; White, N.J. Travel Med Infect Dis, 2016, 14, 548-550.

CrossRef - Noedl, H.; Socheat, D.; Satimai, W. N Engl J Med, 2009, 361, 540-1.

CrossRef - Hasan, M.A.; Mazumder, M.H.; Chowdhury, A.S.; Datta, A.; Khan, M.A. Source Code Biol Med, 2015, 10, 7.

CrossRef - Kumari, M.; Chandra, S.; Tiwari, N.; Subbarao, N. BMC Struct Biol, 2016, 16, 12.

CrossRef - Potshangbam, A.M.; Tanneeru, K.; Reddy, B.M.; Guruprasad, L. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2011, 21, 7219-23.

CrossRef - Raza, M.; Khan, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Raza, S.; Khan, A.; Mohammadzai, I.U.; Zada, S. Comput Biol Chem, 2017, 71, 10-19.

CrossRef - Sanderson, T.; Rayner, J.C. Wellcome Open Res, 2017, 2, 45.

CrossRef - Deroost, K.; Opdenakker, G.; Van den Steen, P.E. Trends Parasitol, 2014, 30, 309-16.

CrossRef - Bensch, S.; Hellgren, O.; Perez-Tris, J. Mol Ecol Resour, 2009, 9, 1353-8.

CrossRef - Aurrecoechea, C.; Brestelli, J.; Brunk, B.P.; Dommer, J.; Fischer, S.; Gajria, B.; Gao, X. ;Gingle, A.; Grant, G.; Harb, O.S.; Heiges, M.; Innamorato, F.; Iodice, J.; Kissinger, J.C.; Kraemer, E.; Li, W.; Miller, J.A.; Nayak, V.; Pennington, C.; Pinney, D.F.; Roos, D.S.; Ross, C.; Stoeckert, C.J., Jr.; Treatman, C.; Wang, H. Nucleic Acids Res, 2009, 37, D539-43.

CrossRef - Jaschke, A.; Coulibaly, B.; Remarque, E.J.; Bujard, H.; Epp, C. Clin Vaccine Immunol, 2017.

- Samant, M.; Chadha, N.; Tiwari, A.K.; Hasija, Y. Int J Med Chem, 2016, 2016, 2741038.

- Meissner, K.A.; Lunev, S.; Wang, Y.Z.; Linzke, M.; de Assis Batista, F.; Wrenger, C.; Groves, M.R. Curr Drug Targets, 2017, 18, 1069-1085.

CrossRef - Zhang, V.M.; Chavchich, M.; Waters, N.C. Curr Top Med Chem, 2012, 12, 456-72.

CrossRef - Mariuba, L.A.; Orlandi, P.P.; Medeiros, M.; Holanda, R.; Grava, A.; Nogueira, P.A. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, 2008, 103, 522-7.

CrossRef - Cousins, K.R. J Am Chem Soc, 2011, 133, 8388.

CrossRef - Li, Z.; Wan, H.; Shi, Y.; Ouyang, P. J Chem Inf Comput Sci, 2004, 44, 1886-90.

CrossRef - Southan, C.; Stracz, A. J Cheminform, 2013, 5, 20.

CrossRef - Fernandez-Recio, J.; Totrov, M.; Abagyan, R. Pac Symp Biocomput, 2002, 552-63.

- Zak, A.K.; Razali, R.; Majid, W.H.; Darroudi, M. Int J Nanomedicine, 2011, 6, 1399-403.

- Bozetine, H.; Wang, Q.; Barras, A.; Li, M. ; Hadjersi, T.; Szunerits, S.; Boukherroub, R. J Colloid Interface Sci, 2016, 465, 286-94.

CrossRef - Punnoose, A.; Dodge, K.; Rasmussen, J.W.; Chess, J.; Wingett, D.; Anders, C. ACS Sustain Chem Eng, 2014, 2, 1666-1673.

CrossRef - Khalil, A.T.; Ovais, M.; Ullah, I.; Ali, M.; Khan Shinwari, Z.; Maaza, M. Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews, 2017, 10, 186-201.

CrossRef - Wang, S.X.; Pandey, K.C.; Somoza, J.R.; Sijwali, P.S.; Kortemme, T.; Brinen, L.S.; Fletterick, R.J.; Rosenthal, P.J.; McKerrow, J.H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006, 103, 11503-8.

CrossRef - Wang, S.X.; Pandey, K.C.; Scharfstein, J.; Whisstock, J.; Huang, R.K.; Jacobelli, J.; Fletterick, R.J.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Abrahamson, M.; Brinen, L.S.; Rossi, A.; Sali, A.; McKerrow, J.H. Structure, 2007, 15, 535-43.

CrossRef - Barennes, H.; Kahiatani, F.; Pussard, E.; Clavier, F.; Meynard, D.; Njifountawouo, S.; Verdier, F. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 1995, 89, 418-21.

CrossRef - Sowunmi, A.; Salako, L.A.; Laoye, O.J.; Aderounmu, A.F. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 1990, 84, 626-9.

CrossRef - Maldonado, C.; Barnes, C.J.; Cornett, C.; Holmfred, E.; Hansen, S.H.; Persson, C.; Antonelli, A.; Ronsted, N. Front Plant Sci, 2017, 8, 391.

CrossRef - Pandey, S.K.; Dwivedi, H.; Singh, S.; Siddiqui, W.A.; Tripathi, R. Parasitology, 2013, 140, 406-13.

CrossRef - de Villiers, K.A.; Gildenhuys, J.; le Roex, T. ACS Chem Biol, 2012, 7, 666-71.

CrossRef - Karczmarzyk, Z.; Lipinska, T.M.; Wysocki, W.; Denisiuk, M.; Piechocka, K. Acta Crystallogr C, 2011, 67, o346-9.

CrossRef - Shen, Z.; Chen, T.; Ma, X.; Ren, W.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Ruan, H.; Fan, W.; Lin, L.; Munasinghe, J.; Chen, X.; Wu, A. ACS Nano, 2017, 11, 10992-11004.

CrossRef - Ahmed, M.S.U.; Salam, A.B.; Yates, C.; Willian, K.; Jaynes, J.; Turner, T ;Abdalla, M.O. Int J Nanomedicine, 2017, 12, 6973-6984.

CrossRef - Yen, S.K.; Padmanabhan, P.; Selvan, S.T. Theranostics, 2013, 3, 986-1003.

CrossRef - Zhang, L.; Dong, W.F.; Sun, H.B. Nanoscale, 2013, 5, 7664-84.

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.