Abstract

In order to combat climate change, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from industry, transportation, buildings, and other sources need to be captured and long-term stored. Decarbonization of these sources requires special types of materials that have high affinities for CO2. Potassium hydroxide is a benchmark aqueous sorbent that reacts with CO2 to convert it into K2CO3 and subsequently precipitated as CaCO3. Another class of carbon capture materials is solid sorbents that are usually functionalized with amines or have natural affinities for CO2. The next wave of materials for carbon capture under investigation includes activated carbon, metal–organic frameworks, zeolites, carbon nanotubes, and ionic liquids. In this issue of MRS Bulletin, some of these materials are highlighted, including solvents and sorbents, membranes, ionic liquids, and hydrides. Other materials that can capture CO2 from low concentrations of gas streams, such as air (direct air capture) are also discussed. Also covered in this issue are machine learning-based computer algorithms developed with the goal to speed up the progress of carbon capture materials development, and to design advanced materials with high CO2 capacity, improved capture and release kinetics, and improved cyclic durability.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 2021, it is clear that human activities have warmed the atmosphere, ocean, and land. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have increased dramatically since the industrial revolution (1750). Specifically, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration now approaches 420 ppm, whereas methane (CH4) reached 1866 ppb, and nitrous oxide (N2O) reached 332 ppb. As a result, fast and extensive variations in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere have occurred.1 Land and ocean have taken up globally about 56% per year of CO2 emissions from human activities over the past six decades.1

According to Berkeley Earth and UK Hadley Center, the global mean temperature in 2020 is estimated as 1.27°C above the average temperature in the late nineteenth century. In 2021, climate anomalies, including severe drought, wildfires, flooding, melting of arctic ice, and stronger hurricanes were already experienced. IPCC has shown that if the CO2 emissions as a function of time will continue as business as usual, the rise in global surface temperature will reach 4°C. If this scenario materializes, the earth’s environment will become intolerable for humans and many other life forms on the planet. In response to this global threat, in December 2015, talks at the Paris meeting have identified the need for immediate action aimed at reducing CO2 emissions to limit the increase of global temperatures between 1.5°C and 2°C.2

Considering the continuing increase in atmospheric CO2, and the slow pace of decarbonization, carbon capture becomes a last-resort response for mitigation of global warming and climate change. Along this line, we need technologies that can be deployed in a wide variety of situations at low cost and massive scale to capture CO2 from power plants fired with coal or natural gas, flue gas from industrial plants, the tailpipes of cars and trucks, and legacy emissions from the air (direct air capture). The captured CO2 can be permanently stored in the ground, or used for making useful products such as fuel, concrete, drinks, urea fertilizer, and so on. Thus, the development of effective methods of capturing carbon dioxide from various gas streams has become essential. Based on the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) scenario, CO2 capture from point sources has to scale up from 40M tons per year today to 6.6B tons in 2050. Direct air capture (DAC) of CO2 has to grow from a few thousand tons per year to nearly 1B tons to reach net-zero emission by 2050.3,4

Because carbon capture is a multiscale problem, it is most appropriate to use different CO2 capture methods for different emission sources. Figure 1 depicts the global contributions of large industrial point sources, showing different CO2 concentrations in the emitted gas streams. For example, natural gas and ethanol refineries emit up to 80% CO2. Iron and steel, and coal power plants emit about 20–30% and 12–15% CO2, respectively. CO2 concentration in ambient air is about 0.042 percent. A 550-MW coal-fired power plant capturing 90% of the emitted CO2 needs to separate about 5 Mton of CO2 per year. Therefore, carbon capture materials and technologies need to be appropriate for the specific CO2 emission source (i.e., high or low CO2 partial pressure or gas stream volume).

Concentration of CO2 emissions from large industrial point sources. Graph is generated from the data in Reference 5.

Current carbon capture technologies

Some of the current strategies for CO2 mitigation and negative emissions are as follows: (1) switching to nuclear, solar, wind, hydro, etc., for renewable energy production; (2) carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS); and (3) negative emission technologies (i.e., bioenergy with carbon capture and storage [BECCS], DAC, reforestation, afforestation, etc.).

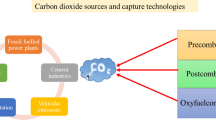

There are diverse classes of materials already employed or under investigation for carbon capture. These include activated carbon, MOFs, cellulose, zeolites, silica gels, carbon nanotubes, and others. Figure 2 depicts some of the sources for carbon emissions, the capture of CO2 using special classes of materials, and the storage of captured CO2.

One of the benchmarks for CO2 capture from flue gas sources comprises amine solvents. Either a single amine or a blend of two or more amines in aqueous solutions are commonly used to scrub the CO2. This traditional amine-based process established the benchmark for flue gas carbon capture. For example, ethanolamine is an absorbent that interacts with CO2 and forms carbamate. This occurs at around 40–60°C, a fairly low-temperature process. Once the sorbent is saturated with CO2, it needs to be regenerated by releasing the CO2. The desorption can occur through temperature, pressure, or electric potential swing. This step is the most energy-demanding in the process and has a major impact on the cost of carbon capture. Furthermore, water evaporation increases steam requirement, which increases the parasitic load and the cost of carbon capture. Thus, reducing the water content in the solution can result in larger net-CO2 carrying capacity of the solvent, thereby leading to energy savings. However, this may also increase the viscosity of the solvent, which slows down the CO2 mass transfer and makes solvent recirculation more difficult. Most of the amines are volatile, toxic, and nonbiodegradable. This can be a health and environmental concern. Moving forward, new approaches to reduce the water content without increasing viscosity too much and enhance the energy efficiency of solvent regeneration are some of the main R&D focus areas.

While efforts to improve and optimize the amine solvents will continue, the excessive amount of energy required for their regeneration remains a major setback, which calls for the development of alternative CO2 capture materials. The main alternative to amine solvents for CO2 capture is solid sorbent. Alkaline sorbents such as lithium hydroxide (LiOH) have been used for the removal of CO2 at low concentration from air (<1%), in spacecraft. Zeolites, silica gels, activated carbons, amine-supported sorbents, and MOFs are some of the sorbents currently used in carbon capture applications. These materials are operated either by physical adsorption (physisorption) or by chemical adsorption (chemisorption) mechanisms. Activated carbons, for example, exhibit the physisorption capture mechanism. This is a low-heat adsorption process that requires less energy, up to +40 kJ/mol, to desorb the CO2. Unfortunately, due to the weak interactions involved, physisorbent materials tend to have low selectivity for CO2. On the other hand, amine-grafted chemisorbents have a higher CO2 capture capacity and selectivity, but may react irreversibly with contaminant species in flue gas, such as SO2, which lowers their CO2 removal capacity. Like the amine solvents, chemisorbents may involve high energies to desorb the CO2, up to 100 kJ/mol, and can be susceptible to chemical degradation, making the overall carbon capture process expensive.

Membranes are quickly becoming a good alternative for CO2 capture, especially from flue gas at power plants. Membranes that are engineered to be more permeable and selective for CO2 and against competing gases, such as N2, O2, and water vapor, may lead to energy-efficient CO2 capture technologies. The high selectivity and modularity of membranes make them desirable for a range of CO2 point source applications with different CO2 partial pressures involved in the power sector, chemical industry, or cement and steel plants.

Table I summarizes and compares different solvents and materials currently employed in carbon capture, with their advantages and shortcomings. Some of these materials are highlighted in this issue of MRS Bulletin, including solvents and sorbents, membranes, ionic liquids, and hydrides.

In this issue

This issue highlights some promising new materials for CO2 capture, such as ionic liquids, DAC sorbents, membranes, and solid borohydrides, as well as new approaches for accelerated design of such materials based on machine learning.

Jiang et al.6 make a strong case for employing ionic liquids for carbon capture. Ionic liquids boast low vapor pressure, high thermal stability, and great tunability, which make them attractive for carbon capture applications via physisorption or chemisorption. The interactions with CO2 can be precisely tuned by modifying the basicity of the anion, while the overall performance (e.g., viscosity, stability) can be improved by controlling the cation and the cation–anion interactions. Ionic liquids can be deployed either as solvents, or as supported liquid membranes. Particularly exciting are composite materials that combine the ionicity and reactivity of ionic liquids with the porosity of the support materials, leading to enhanced CO2 transport and selectivity.

Chen et al.7 summarize the recent progress in the development of sorbent materials for direct air capture. The very low concentration of CO2 in the air (0.042 vol%) makes DAC the most difficult carbon capture approach, requiring sorbents with very strong and selective binding, which in turn leads to the challenge of keeping the sorbent regeneration energy low enough for sustainable and cost-effective technologies. This article focused on five technologies for DAC, based on the following: physisorption with porous frameworks (e.g., zeolites, metal–organic frameworks), chemisorption with strong alkaline bases (e.g., KOH, MgO), solid-supported amine sorbents, phase-changing aqueous amino acids/crystalline guanidine sorbents, and moisture-swing sorbents.

A different approach to DAC, based on membrane separation, is presented by Fujikawa et al.8 Although membranes are generally considered for CO2 separation from more concentrated streams, such as flue gas or other industrial sources, the case is made here that recent developments in membrane technology have brought the possibility of certain membrane processes to be considered for DAC. Although the purity and concentration of the resulting CO2 are not as high as with other DAC approaches, the flexibility and modularity of membranes offer distinct advantages that allow deployment in unconventional urban settings.

Lombardo et al.9 introduce an innovative approach that combines CO2 capture with reduction using solid borohydride sorbents. The structures, porosities, and reactivity of these materials toward CO2 can be systematically tuned through nanoconfinement or careful selection of the countercations. This approach may lead to integrated carbon capture/conversion technologies that produce value-added product from different sources of CO2.

The development of porous materials for carbon capture has relied mostly on trial-and-error approaches or serendipitous discoveries, leading to slow progress of this research field. Lin et al.10 describe a new approach to the design of carbon capture materials, like porous carbons or metal–organic frameworks, based on machine learning (ML). ML can greatly accelerate the rate of discovery of this class of materials, based on quick analysis of large data sets from the literature, or generated by computer algorithms. The authors anticipate ML will provide unique insight and guidance for the design of the next-generation porous materials with advanced carbon capture functionalities.

Outlook

Moving forward, many exciting developments in the areas of carbon capture materials such as solid sorbents, liquid solvents, or membranes are emerging. Many startups are looking into more economic ways to capture carbon from different emission sources, with an increasing emphasis on DAC.12 Implementing new advanced materials into more modular capture technologies provides an alternative to large-scale centralized facilities for the next-generation carbon capture technologies such as DAC. To this end, for the solid sorbent materials, research needs to focus on improving CO2 uptake capacity, faster capture and release kinetics, improved lifetime, enhanced CO2 selectivity, and lower regeneration energy. Particles with large surface areas and topographies that combine meso-/micro-/nanoporosities can be designed and synthesized for advanced carbon capture materials. In addition, ease of scaleup that does not require expensive raw materials and energy-intensive syntheses, thereby assuring low-cost sorbent manufacturing, are also important focus areas. This is especially critical for reducing the manufacturing costs associated with large-scale production of designer sorbents such as MOFs. For the solvent approach, future research needs to focus on alternative regeneration methods that avoid heating the bulk liquid and minimize the regeneration energy. The development of novel water-lean solvents with higher cyclic capacities and lower energetic requirements are also of high priority.13 CO2 capture from air by membranes has the potential to be energy-efficient and modular, as long as their permeability and selectivity for CO2 under DAC conditions can be improved, and the concentration of CO2 in the effluent can be increased. In addition, the high material and manufacturing costs of membrane separation technologies are also impeding their DAC application and more progress along these lines is needed before membranes can be deployed in large scale.11 While fundamental research developments continue to be important, rapid implementation of these new classes of materials beyond bench scale, from pilot to industrial scale under real-world conditions, taking advantage of learning-by-doing strategy, has become critical for slowing down and reversing climate change.

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (2021). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/#FullReport

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Adoption of the Paris Agreement, Proposal by the President (UNFCCC, Paris, 2015). http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09.pdf. Accessed 25 Apr 2021

International Energy Agency, Net Zero by 2050, IEA Report (July 2021). https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050

M. Ozkan, MRS Energy Sustain. 8, 51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1557/s43581-021-00005-9

R. Baker, B. Freeman, J. Kniep, Y.I. Huang, T.C. Merkel, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 15963 (2018)

Y. Fu, Z. Yang, S.M. Mahurin, S. Dai, D-Jiang, MRS Bull. 47(4) (2022). https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-022-00315-4

X. Shi, Y. Lin, X. Chen, MRS Bull. 47(4) (2022)

S. Fujikawa, R. Selyanchyn, MRS Bull. 47(4) (2022)

L. Lombardo, H. Yang, S. Horike, A. Züttel, MRS Bull. 47(4) (2022)

C. Zhang, Y. Xie, C. Xie, H. Dong, L. Zhang, J. Lin, MRS Bull. 47(4) (2022)

M. Ozkan, A.-A. Akhavi, W.C. Coley, R. Shang, Y. Ma, Chem 8(1), 141 (2022)

R. Custelcean, Chem 7(11), 2848 (2021)

D.J. Heldebrant, P.K. Koech, V.A. Glezakou, R. Rousseau, D. Malhorta, D.C. Cantu, Chem. Rev. 117(14), 9594 (2017)

Acknowledgments

R.C. acknowledges support by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division, for editing this issue and writing the cover article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ozkan, M., Custelcean, R. & Guest Editors. The status and prospects of materials for carbon capture technologies. MRS Bulletin 47, 390–394 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-022-00364-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1557/s43577-022-00364-9