Abstract

The objective of this paper is to develop a new wheel-rail contact model, which is suitable for considering the effect of wheelset bending deformation on wheel-rail contact behavior at high speeds. Dummies of the two half rigid wheelset are introduced to describe the spacial positions of the wheels of the deformed wheelset. In modeling the flexible wheelset, the first two wheelset bending modes are considered. Based on the modal synthesis method, these mode values of the wheelset axle are used to solve the motion equations of the flexible wheelset axle modeled as an Euler-Bernoulli beam. The wheel is assumed to be rigid and always perpendicular to the deformed axle at the wheel centre. In the vehicle model, two bogies and one car body are modeled as lumped masses. Spring-damper elements are adopted to model the primary and secondary suspension systems. The ballasted track is modeled as a triple layer discrete elastic supported model. Two high-speed vehicle-track models, one considering rigid wheelset models and the other considering flexible wheelset models, are used to analyze the differences of the numerical results of the two models in both frequency and time domains. In the simulation, a random high-speed railway track irregularity is used as wheel-rail excitations. Wheel-rail forces are calculated and analyzed in the time and frequency domains. The results clarify that this new contact model can characterize very well the influence of the first two bending modes of the wheelset on contact behavior.

概要

研究目的

扩展动力学模型的分析频域, 建立能考虑轮对柔性的车辆轨道耦合动力学系统模型, 为研究轮轨磨耗的形成和发展以及轮轨噪声的来源提供基础。

创新要点

利用欧拉梁横向弯曲模型, 建立轮轴在垂直于轨道平面和平行于轨道平面内的弯曲振动模型; 建立考虑轮轴弯曲的轮对模型与轮轨接触模块之间的耦合关系, 进而研究轮轨接触行为受轮轴弯曲变形的影响。 研究方法: 1. 把轮轴模拟为欧拉梁, 左右车轮模拟为固结于轮轴上的质量块; 2. 假设左右车轮始终垂直于轮轴, 引入虚拟的两个半边刚性轮对模型, 建立轮轨接触模型和柔性轮对耦合的关系; 3. 基于多刚体车辆-轨道耦合动力学模型, 利用以上柔性轮对模型和此耦合关系, 建立考虑轮轴柔性的车辆-轨道耦合动力学模型。

重要结论

1. 建立的刚柔耦合的车辆-轨道耦合动力学模型能够有效地描述轮轴弯曲对轮轨接触行为的影响; 2. 在0–150 Hz的随机不平顺激励下, 多刚体模型和考虑轮对柔性的模型受到的轮轨力和轮轨接触点轨迹不同; 这主要是由第1阶弯曲模态被激发导致。

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

High-speed railways are currently popular globally. However, there are some problems including passenger riding comfort, noise pollution, and even operational safety (Jin et al., 2013). Rail corrugation, rail welding irregularity, wheel burning, and wheel out-of-roundness (OOR) generate high-frequency components of the dy-namic wheel-rail contact forces that contribute signifi-cantly to the total wheel-rail contact forces (Nielsen et al., 2003), and reduce the life of the components of track and vehicle, such as wheels, rails, and fasteners. Rail grinding and wheel re-profiling are the most common measures that have been proved to be effective in con-trolling rail irregularities and wheel OOR. However, these measures lead to notably high maintenance costs. A lot of measurements at the sites and coupling vehicle-track dynamics modeling have been carried out to in-vestigate the mechanism and development of these phenomena. In the vehicle-track dynamics modeling, a rigid multi-body system is often adopted to simulate railway vehicles, based on several commercial codes available for the low-frequency domain, such as GENSYS, NUCARS, SIMPACK, and VAMPIRE. These computer programs are generally used to analyze railway vehicle dynamics responses at frequen-cies below 20 Hz, where the influence of rigid motions of the vehicle on wheel-rail contact forces is dominant (Nielsen et al., 2005). To analyze the vehicle dynamic responses at mid- and high-frequencies, the vehicle structural flexibility should be taken into account in the modeling. It is obvious that wheelset structural flexibil-ity has an influence on wheel-rail contact behaviors at mid- and high-frequencies. Different flexible wheelset models have been set up due to various motivations in the past (Chaar, 2007).

The methods applied to modeling flexible wheelset can be summarized as three major categories (Chaar, 2007). The first is a lumped model developed in a simple and convenient way, in which a wheelset is divided into several parts interconnected with springs and dampers. This model can describe the bending and torsional mo-tions of the wheelset with only a few degrees of free-dom, which could not be applied to studying wear phenomena on wheel treads or rails (Popp et al., 1999). The second is a continuous model developed by Szolc (1998a; 1998b), in which the wheelset axle was modeled as a beam, and two wheels and brake discs were mod-eled as rigid rings attached to the axle through a mass-less, elastically isotropic membrane. The model can characterize the wheelset dynamic behavior in the fre-quency range of 30–300 Hz. In the model proposed by Popp et al. (2003), the wheelset axle was considered as a 1D continuum, having the properties of a bar, a torsional rod, and a Rayleigh beam. The wheel was considered as a 2D continuum, having the proper-ties of a disc and a Kirchhoff plate. The third was de-veloped based on finite element method (FEM), which simulates wheelset flexibility more realistically than the first two categories of model. The wheelset modes and corresponding natural frequencies were obtained through the modal analysis of the finite element (FE) model by using the commercial software, and they were input into the simulation by means of the commercial codes (SIMPACK, NEWEUL) (Meinders and Meinker, 2003) or some non-commercial multi-body dynamic system codes. The non-commercial code developed by Fayos et al. (2007) and Baeza et al. (2008; 2011) introduced the Eulerian coordinate system to replace the Lagrangian coordinate system in the flexible wheelset modeling. In this way it is convenient to obtain the motion of fixed physical nodes, and consider the inertial effect due to wheelset rotation. Relying on cur-rent computing power, it is feasible to use FEM to con-sider the effect of flexible wheelset in modeling a rail-way vehicle coupling with a track.

Regarding the wheel-rail contact treatment in con-sidering flexible wheelset influence, wheel-rail rolling contact condition is simplified based on different prior assumptions, especially in the detection of wheel-rail contact points. This is the prerequisite for the calculation of wheel-rail creepages and contact forces. Baeza et al. (2011) neglected the effect of the high-frequency de-formation and the deviation of a rotating flexible wheelset rolling over a flexible track model on the wheel-rail contact point in the investigation into the effect of the rotating flexible wheelset on rail corruga-tion. Through the detailed calculation Kaiser and Popp (2006) found that the contact point was in the location where the wheel and the rail had positive penetration maxima, and the penetration direction was orthogonal to the common tangent plane of the wheel and the rail before their deformations. A linear wheel-rail contact model was proposed and used to carry out the detection of wheel-rail contact point and the contact zone’s normal direction (Andersson and Abrahamsson, 2002). In the detection, the functions were created using a first-order Taylor expansion around a reference state described by a group of parameters which represent a configuration, in which the train was in static equilibrium and the wheel and the track were free from geometric imperfections. The advantage of this approach is that the contact position and orientation in each time step can be calculated by interpolation replacing iterations, which results in a low computa-tional cost. But the approach is only suitable for the case that the effect of all the parameters is very small on the contact point position and the contact patch orientation around the references is in static equilibrium. The wheel-rail contact point position and the contact patch orientation greatly depend on parameters, such as the curvatures of wheel and rail. In (Torstensson et al., 2012; Torstensson and Nielsen, 2011), the contact point detection was done before the simulation and used in the subsequent time integration analysis in the form of look-up table. The commercial software GENSYS al-lows for such calculations using the pre-processor KPF (from Swedish contact point function). In the KPF, the location and orientation of the contact patch were as-sumed to be dependent only on the relative displacement in the lateral direction between the wheelset and the rails, and hence the influence of the wheelset yaw angle was not taken into account. In some other papers de-tailed discussions on the wheel-rail contact model were omitted. In this study, the wheel-rail contact model considering the effect of wheelset flexibility (Zhong et al., 2013; 2014) is further improved and the new contact model is suitable for the analysis on the effect of the local higher-frequency deformation of the wheels on the wheel-rail contact behavior.

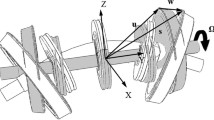

2 Vehicle-track coupling dynamic system

A flexible wheelset model (to be illustrated in Sec-tion 2.1) and a suitable wheel-rail contact model (to be discussed in Section 2.2) are integrated into the vehi-cle-track coupling dynamic system model. All parts of the vehicle system, except for its four wheelsets, are considered as rigid bodies. The primary and secondary suspension systems of the vehicle are modeled with spring-damper elements. A triple layer model of discrete elastic support is adopted to simulate the ballasted track. The rails are modeled as Timoshenko beams. The sleepers are modeled as rigid bodies and the ballast model consists of discrete equivalent masses. The equivalent spring-damper elements are used as the con-nections between the rails and the sleepers, the sleepers and the equivalent ballast bodies, and the ballast bodies and the roadbed. Fig. 1 shows the vehicle-track coupling dynamic system model. The equations of motion of each component of the vehicle excluding wheelsets and the track are illustrated in detail in (Xiao et al., 2007; 2008; 2010). The parameters and their values describing the dynamic models are given in Appendix A.

2.1 Flexible wheelset model

The wheelset structural flexibility is considered by modeling the wheelset axle as an Euler-Bernoulli beam in two planes, one perpendicular to the track centerline and the other parallel to the track level. The crossing effect of the bending deformations in the two planes is ignored. In the first two bending modes obtained using the modal analysis of the FE model of a wheelset, two wheels have little deformation (Fig. 2), and their frequencies are in the available frequency range (0–500 Hz) of an Euler-Bernoulli beam model. Therefore, two wheels can be treated as rigid bodies in this study.

There are two force systems acting on the wheelset, one is the wheel-rail contact forces and the other is the forces of the primary suspension system (Fig. 3).

In Fig. 3, O fL and O fR are the left and right points on the axle, respectively, where the primary suspension force systems are applied. O CL and O CR are the left and right contact points of wheel-rail, respectively. O indicates the origin of the coordinate system O-XYZ that is a coordinate system with a translational motion along the tangent track centerline at operational speed. If the speed is constant, this coordinate system is an inertial coordinate system, and therefore regarded as an absolute coordinate system (geodetic coordinate system).

To analyze the axle’s deformation, the force systems from wheel-rail interaction acting on the left and right wheel treads are translated to the nominal circle centers O L and O R, respectively, and extra moments are produced in the procedure of translating contact forces. Thus, the force systems acting on the axle in the two planes are obtained in Fig. 4.

The notations of the variables and symbols are de-fined in Table 1. The subscript p denotes the primary suspension, the subscripts x, y, and z denote X-, Y-, and Z-direction, respectively, and A denotes the axle.

The differential equation for the flexural vibration of an Euler-Bernoulli beam (the axle) in the plane O-YZ is written as

where

The force analysis diagram of the two wheels in-cluding the D’Alembert forces is shown in Fig. 5, based on which differential equations of motion of the two wheels are written as

Note that the lateral accelerations of the wheels are assumed to be the same as the wheelset axle so there is no relative motion between wheels and axle.

Substituting the expressions of F A(L,R)z and M A(L,R)x obtained through Eqs.(4) and (5) into Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively, we can obtain:

where

Consider a solution of Eq. (8) in the form:

Using the calculus of variation (Qiu et al., 2009), the modal function satisfies:

where δ ij is the Kronecker delta. For i=j, Eq. (11) can be written as

To obtain the mode shape functions with the wheelset axle modeled as a uniform Euler-Bernoulli beam carrying two particles (wheels), the segment of the beam from the left end to the first particle is referred to as the first portion, in between the two particles as the second portion and from the second particle to the right end as the third portion. The beam mode shape will be the superposition of the mode shapes of the three por-tions. The derivation of the mode shape functions is presented in Appendix B. The first three modes have the frequencies of f 1= 111Hz, f 2=245Hz, and f 3=547Hz, respectively. These mode shape functions are normalized so as to satisfy Eq. (14), as shown in Fig. 6. The third mode is not in the fre-quency range of 0–500 Hz where the Euler-Bernoulli beam is available to analyze the system. Hence, the effect of the first two modes on dynamic responses is conducted in this study.

According to the modal analysis, we let the solution of Eq. (8) have the form:

Substituting Eq. (15) into Eq. (8), the differential equation can be written as

Multiplying both sides of Eq. (16) by \(U_{zj}\) and integrating over the domain 0<y<L, we can obtain:

Using the orthogonality of the modal shape function as expressed in Eqs. (11) and (13), Eq. (17) can be written as

where

Eq. (18) can be expressed as

Eq. (20) can be written in the matrix form:

where

The explicit integral method illustrated in (Zhai, 2007) is used to obtain the vector \(\left[ {\ddot q_{zj} } \right]\) of each acceleration coordinate.

For the vibration in the plane YOX, the dif-ferential equation expressed with respect to \(\left[ {\ddot q_{xy} } \right]\) can be written as

The derivation of Eq. (23) is similar to that of Eq. (20) and omitted here. Eq. (23) can be expressed in matrix form:

where

2.2 Wheel-rail contact model

As mentioned in Section 2.1, the main concern in this work is the wheelset axle bending. The wheels are assumed to be rigid and their nominal rolling circles are always perpendicular to the deformed wheelset axle at their interference fit surfaces. Fig. 7 shows that the flexible wheelset moves from its initial reference state (O 1(t 1)) to its t 2 status (O 2(t 2)), which is described in the plane of O-YZ. O 1 is the center of the un-deformed wheelset at t 1, and O 2 is the center of the deformed wheelset at any time t. O 1 O 2 is the displacement vector of the wheelset center due to its rigid motion, and ϕ R1 is the roll angle due to the wheelset rigid motion. The auxiliary line, \(A_{\text{L}}^0 A_{\text{R}}^0\), is the central line of the un-deformed wheelset axle, \(A_{\text{L}}^1 A_{\text{R}}^{\text{1}}\) is obtained by moving \(A_{\text{L}}^0 A_{\text{R}}^0\) from O 1(t 1) to O 2(t 2), and \(A_{\text{L}}^2 A_{\text{R}}^2\) is obtained through rotating \(A_{\text{L}}^1 A_{\text{R}}^1\) by ϕ R1. \(A_{\text{L}}^2 A_{\text{R}}^2\) is actually the central line of the rigid wheelset axle at t 2. Fig. 7 shows that the wheels are assumed to be rigid and always perpendicular to the deformed axle line at their connections at any time t 2.

To clearly describe the new wheel-rail contact model, the dummies of the two rigid half wheelsets, as shown in Fig. 8, are employed to describe wheel-rail rolling contact behavior affected by the wheelset bending. The two dummies are indicated by DWL and DWR, respectively, and the wheels of the DWL and the DWR are assumed to overlap the left and right wheels of the flexible wheelset, respectively, all the time, namely, the motion of the assumed rigid wheels of the flexible wheelset can be described by the DWL and the DWR (Fig. 8). ϕ R2 is the roll angle of the right wheel due to the bending deformation of the flexible wheelset. It is exactly the included angle between the line \(A_{\text{L}}^2 A_{\text{R}}^2\) and the axle line of the right wheel or the wheel of the DWR.

It is not difficult to calculate the wheel-rail contact geometry considering the effect of the flexible defor-mation of the wheelset or the local high-frequency deformations of the wheels if the spatial po-sitions of the DWL and the DWR are determined. De-termining the spatial positions of the DWL and the DWR involves calculating their motion parameters, such as the lateral displacements of the centers of the wheels of the DWL and the DWR, indicated by y DWL and y DWR, respectively, the vertical displacements, z DWL and z DWR, the roll angles, ϕ DWL and ϕ DWR, and the yaw angles, ψ DWL and ψ DWR. These parameters are key to calculating the contact geometry of the flexi-ble wheelset in rolling contact with a pair of rails by using this new wheel-rail contact model. This will now be demonstrated in detail.

Fig. 8 describes the motion of the DWL and the DWR influenced by the wheelset bending and its rigid motion in the O-YZ plane only. After the rigid wheelset moves with the center displacement of O 1 O 2 and the rolling angle of ϕ R1 in the O-YZ plane of the global reference, O-XYZ, its center position O 1(t 1) reaches the position O 2(t 2) and \(A_{\text{L}}^0 A_{\text{R}}^0\) reaches (or becomes) \(A_{\text{L}}^2 A_{\text{R}}^2\). Note that the vector O 1 O 2 and the roll angle ϕ R1 around axis X are described in the O-YZ plane. The dash-dot line \(A_{\text{L}}^1 A_{\text{R}}^1\) is through point O 2(t 2) and parallel to \(A_{\text{L}}^0 A_{\text{R}}^0\). From Fig. 6, it is obvious that the rolling angle of the DWR caused by the wheelset rigid motion is just ϕ R1, and that caused by the wheelset bending deformation is ϕ R2, so the total rolling angle of the DWR is ϕ DWR ϕ R1+ϕ R2, as shown in Fig. 6.

In addition, the displacement of the DWR is the vector O 1 O 3R, which could be written as

In Fig. 8, the vector O 2 A 1 is parallel to O 3R A 2 with the same length l 0. l 0 is actually the distance between the center of the wheel nominal circle and the center of the un-deformed wheelset. The vector O 2 O 3R is parallel to A 1 A 2, with the same length. Thus, O 1 O 3R can be written as

Moreover, the vector O 2 A 1 is described by {x 1 y 1 z 1}[i j k]T in O-XYZ, and can be obtained by rotating the vector {0 l 0 0}[i j k]T (coinciding with the line \(A_{\text{L}}^1 A_{\text{R}}^{\text{1}}\)) about the X-axis by ε DWR. O 2 A 1 is written as

The curve \(\widehat{B_{\text{L}} B_{\text{R}}}\) (Fig. 6) is the deformed axle center line of the wheelset, which does not consider the influence of the rotation caused by the wheelset rigid motion. The point B R is the center of the right nominal circle. The axle center line \((\widehat{O_{\text{2}} A_{\text{2}} })\) of the deformed wheelset, can be obtained by rotating \(\widehat{B_{\text{L}} B_{\text{R}}}\) about the X-axis by ϕ R1. According to the definition of the curve \(\widehat{B_{\text{L}} B_{\text{R}}}\), the vector O 2 B R is defined as

where {Δx 2 Δy 2 Δz 2}[i j k]T is the displacement vector of the center of the right nominal circle due to the axle bending. Then the vector O 2 A 2 is defined as {x 3 y 3 z 3}[i j k]T, and can be written as

which is obtained according to the relationship between \(\widehat{O_{\text{2}} A_{\text{2}}}\) and \(\widehat{O_{\text{2}} B_{\text{R}}}\), or \(\widehat{O_{\text{2}} A_{\text{2}}}\) obtained by rotating \(\widehat{O_{\text{2}} B_{\text{R}}}\) by ϕ R1. The wheelset center displacement vector O 1 O 2 is defined as {x 0 y 0 z 0}[i j k]T.

Substituting Eqs. (28) and (30) and the expression of O 1 O 2 into Eq. (27), the vector O 1 O 3R can be written as

Similarly, when considering the wheelset bending deformation in the plane O-XY, the vector >O 1>O 3R should be given as

where ψ R1 and ψ R2 are the yaw angles caused by the rigid motion and the bending deformation in the plane O-XY, respectively.

ψ DWR=ψ R1+ ψ R2 is the total yaw angle of the DWR. Similarly, the position of the DWL can be obtained. When the positions of the two dummies are known at t 2, the wheel-rail contact geometry can be calculated. Then the positions of the wheel-rail contact points are easily found and the wheel-rail contact forces can be calculated. The normal wheel-rail contact forces are calculated by the Hertzian nonlinear contact spring model, and the tangent contact forces and spin moments are calculated by means of the model by Shen et al. (1983). Compared with the con-ventional wheel-rail contact model (Wang, 1984; Zhai, 2007), this new wheel-rail contact model can charac-terize the independent high-frequency deformations of the two wheels of the flexible wheelset more conveniently.

3 Results and discussion

When a vehicle is running on an ideal track, it is only excited by sleepers. Note that the “flexible” wheelset model used in this section denotes the model considering the first two bending modes. The dynamic system with flexible wheelset models is used in the simulation on an ideal track at the speed of 300km/h. Figs. 9a and 9b show the vertical forces in the frequency domain in steady and unsteady stages, respectively. In the unsteady stage, the peaks appear not only at a set of harmonic frequencies nf s (n=1, 2, 3, …) produced by passing sleeper but also at f b1, while the influence of the second bending mode is small since there is no peak at f b2. In the steady stage, the contribu-tion of the component at f b1 is weak-ened and only the peaks at nf s (n=1, 2, 3, …) remain. These results are reasonable because when a system comes to a steady stage, its responses only contain the component at the excitation frequency.

Based on a large range of site measurements, the components of roughness on rails mostly appear in the range of 1–20 m. The natural frequencies of the first two bending modes are below 250Hz, meaning the available frequency of this model is limited. Therefore, the components of the random irregularity on the rails are mainly in the frequency range of 0–150 Hz at the speed of 300 km/h. Fig. 10a presents the local section of 900–950m in the time domain, and Fig. 10b shows the irregularity in the frequency domain. Note that the results below are from the steady stage.

Figs. 11 and 12 show the wheel-rail contact forces acting on the rigid and flexible wheelsets in the time and frequency domains, respectively. As shown in Fig. 11a, the average of the oscillation of the lateral contact force acting on the flexible model is a little smaller than that on the rigid wheelset model, and the shapes of the os-cillation are different. As shown in Fig. 11b, the vertical contact forces acting on the two models oscillate around a similar average, while their shapes are different. These differences are caused by the wheelset flexibility.

In the frequency domain, the distributions of the components contained in both the lateral and vertical contact forces are in the excitation frequency range of the random irregularity. A peak at frequency 2f s appears in Figs. 11a and 11b. The contribution of the component at frequency f s is overwhelmed by the effect of the irregularity. In addition, the uniform distribution in 0–150 Hz of the irregularity results in the non-uniform distribution of contact forces. As shown in Figs. 12a and 12b, the components in 80– 150 Hz are higher than those in 0–80 Hz. This shows that under this present irregularity, this dynamic system is more sensitive to the excitation in 80– 150Hz than to those in 0–80 Hz.

In the frequency domain, the component at f b1 of the lateral contact force acting on the flexible model is a little larger than that on the rigid model, as marked using the arrow in Fig. 12a. This shows that the first bending mode is excited, and the availability of the model to characterize the wheelset bending is proved. However, there is no evident differ-ence at f b1 for vertical contact forces acting on the two models. This shows that the wheelset bending deformation has a stronger effect on the lateral contact force than on the vertical contact force.

The wheel-rail contact force is affected by the posi-tion of the lateral contact points. Figs. 13a and 13b show the oscillations of the contact points in lateral direction described in the body coordinate system attached to the rail cross-section in the time and frequency domains, respectively. The average of the magnitudes of oscilla-tion of the contact points on the flexible model in the time domain is larger than that on the rigid model. This is caused by the wheelset bending. Moreover, it can weaken the relative movement between rail and wheel caused by the irregularity. Therefore, it is one cause of the smaller average of the lateral contact force acting on the flexible model (Fig. 11a). As shown in Fig. 13b, the difference of the components between the two models at f b1 is evident. This explains the difference in the time domain (Fig. 13a) and again shows the effectiveness of the proposed model.

4 Conclusions

In this study a new wheel-rail contact model is integrated into the high-speed vehicle-track coupling dynamics system model, which takes into account the effect of wheelset structural flexibility. Based on the new vehicle-track model the effect of the first two bending modes of the wheelset on wheel-rail contact behavior is analyzed under the random irregularity in a frequency range of 0–150 Hz. The numerical results of the rigid wheelset model and the flexible wheelset model are compared in detail. The following conclusions can be drawn from the results:

-

1.

The present vehicle-track model considering flexible wheelsets can very well characterize the effect of the flexible wheelset on wheel-rail dynamic behavior.

-

2.

Under the excitation, the shapes of the oscillations of the wheel-rail contact forces and contact points for the new and conventional vehicle-track models are differ-ent. The difference is caused by the excited first bending mode of the wheelset.

For future work, the first improvement to be con-sidered is to model a wheelset using the FEM or the Timoshenko beam theory to broaden the model’s available frequency range. This could allow it to help investigate the mechanisms behind the generation and development of wheel-rail wear and noise.

References

Andersson, C., Abrahamsson, T., 2002. Simulation of interaction between a train in general motion and a track. Vehicle System Dynamics, 38(6):433–455. [doi:10.1076/vesd.38.6.433.8345]

Baeza, L., Vila, P., Rodaa, A., et al., 2008. Prediction of corrugation in rails using a non-stationary wheel-rail contact model. Wear, 265(9–10):1156–1162. [doi:10.1016/j.wear.2008.01.024]

Baeza, L., Vila, P., Xie, G., et al., 2011. Prediction of rail corrugation using a rotating flexible wheelset coupled with a flexible track model and a non-Hertzian/non-steady contact model. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 330(18–19): 4493–4507. [doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2011.03.032]

Chaar, N., 2007. Wheelset Structural Flexibility and Track Flexibility in Vehicle/track Dynamic Interaction. PhD Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden.

Fayos, J., Baeza, L., Denia, F.D., et al., 2007. An Eulerian coordinate-based method for analysing the structural vibrations of a solid of revolution rotating about its main axis. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 306(3–5):618–635. [doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2007.05.051]

Jin, X.S., Xiao, X.B., Ling, L., et al., 2013. Study on safety boundary for high-speed train running in severe environments. International Journal of Rail Transportation, 1(1–2):87–108. [doi:10.1080/23248378.2013.790138]

Kaiser, I., Popp, K., 2006. Interaction of elastic wheel-sets and elastic rails: modeling and simulation. Vehicle System Dynamics, 44(S1):932–939. [doi:10.1080/00423110600 907675]

Meinders, T., Meinker, P., 2003. Rotor dynamics and irregular wear of elastic wheelsets, system dynamics and long-term behavior of railway vehicles, track and subgrade. System Dynamics and Long-term Behaviour of Railway Vehicles, Track and Sub-grade, 6133–152. [doi:10.1007/978-3-540-45476-2_9]

Nielsen, J.C.O., Lundén, R., Johansson, A., et al., 2003. Train-track interaction and mechanisms of irregular wear on wheel and rail surfaces. Vehicle System Dynamics, 40(1–3):3–54. [doi:10.1076/vesd.40.1.3.15874]

Nielsen, J.C.O., Ekberg, A., Lundén, R., 2005. Influence of short-pitch wheel/rail corrugation on rolling contact fatigue of railway wheels. Journal of Rail and Rapid Transit, 219(3):177–188. [doi:10.1243/095440905X8871]

Popp, K., Kruse, H., Kaiser, I., 1999. Vehicle/track dynamics in the mid-frequency range. Vehicle System Dynamics, 31(5–6):423–463. [doi:10.1076/vesd.31.5.423.8363]

Popp, K., Kaiser, I., Kruse, H., 2003. System dynamics of railway vehicles and track. Archive of Applied Mechanics, 72(11–12):949–961. [doi:10.1007/s00419-002-0261-6]

Qiu, J.B., Xiang, S.H., Zhang, Z.P., 2009. Computational Structural Dynamics. Press of University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China (in Chinese).

Shen, Z.Y., Hedrick, J.K., Elkins, J.A., 1983. A comparison of alternative creep force models for rail vehicle dynamic analysis. Vehicle System Dynamics, 12(1–3):79–83. [doi:10.1080/00423118308968725]

Szolc, T., 1998a. Medium frequency dynamic investigation of the railway wheelset-track system using a discrete-continuous model. Archive of Applied Mechanics, 68(1): 30–45. [doi:10.1007/s004190050144]

Szolc, T., 1998b. Simulation of bending-torsional-lateral vibrations of the railway wheelset-track system in the medium frequency range. Vehicle System Dynamics, 30(6): 473–508. [doi:10.1080/00423119808969462]

Torstensson, P.T., Nielsen, J.C.O., 2011. Simulation of dynamic vehicle-track interaction on small radius curves. Vehicle System Dynamics, 49(11):1711–1732. [doi:10. 1080/00423114.2010.499468]

Torstensson, P.T., Pieringer, A., Nielsen, J.C.O., 2012. Simulation of rail roughness growth on small radius curves using a non-Hertzian and non-steady wheel-rail contact model. 9th International Conference on Contact Mechanics and Wear of Rail/Wheel Systems, Chengdu, China, p.223–230. [doi:10.1016/j.wear.2013.11.032]

Wang, K.W., 1984. Wheel contact point trace line and wheel/rail contact geometry parameters computation. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, 1:89–99 (in Chinese).

Xiao, X.B., Jin, X.S., Wen, Z.F., 2007. Effect of disabled fastening systems and ballast on vehicle derailment. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, 129(2):217–229. [doi:10.1115/1.2424978]

Xiao, X.B., Jin, X.S., Deng, Y.Q., et al., 2008. Effect of curved track support failure on vehicle derailment. Vehicle System Dynamics, 46(11):1029–1059. [doi:10.1080/0042311 0701689602]

Xiao, X.B., Jin, X.S., Wen, Z.F., et al., 2010. Effect of tangent track buckle on vehicle derailment. Multibody System Dynamics, 25(1):1–41. [doi:10.1007/s11044-010-9210-2]

Zhai, W.M., 2007. Vehicle/Track Coupling Dynamics (3rd Edition). Chinese Science Press, Beijing, China (in Chinese).

Zhong, S.Q., Xiao, X.B., Wen, Z.F., et al., 2013. The effect of first-order bending resonance of wheelset at high speed on wheel-rail contact behavior. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 2013:296106. [doi:10.1155/2013/296106]

Zhong, S.Q., Xiao, X.B., Wen, Z.F., et al., 2014. A new wheel-rail contact model integrated into a coupled vehicle-track system model considering wheelset bending. 2nd International Conference on Railway Technology Research, Development and Maintenance, Ajacocia, France, p.1–10. [doi:10.4203/ccp.104.10]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1134202), the National Basic Research Program (973) of China (No. 2011CB711103), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (Nos. IRT1178 and SWJTU12ZT01), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the 2014 Doctoral Innovation Funds of Southwest Jiaotong University, China

ORCID: Shuo-qiao ZHONG, http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1990-5865; Xue-song JIN, http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3033-758X

Appendices

Appendix A

The vehicle notations and track parameters are given in Table A1.

Appendix B

The axle is modeled as a uniform Euler-Bernoulli beam carrying two particles (wheels). The segment of the beam from the left end to the first particle is referred to as the first portion, in between the two particles as the second portion and from the second particle to the right end as the third portion. The beam mode shape will be the superposition of the mode shapes of the three portions. The mode shape of each portion has four constants of integration, i.e., a total of 12 for the three portions. It is necessary to satisfy: the boundary conditions; continuity of deflection and continuity of slope at the two ‘locations’; and compatibility of bending moments and compatibility of forces acting on the two particles.

Here we take the calculation of the mode shape functions in the plane O-YZ as an ex-ample. Fig. B1 shows a uniform Euler-Bernoulli beam O 1 O 3 of flexural rigidity EI x , and length (R 1+R 2+R 3)L carrying the first particle of mass m w at axial coordinate R 1 L from O 1 and the second particle of mass m w at axial coordinate R 3 L from O 3.

To write the equations of transverse vibrations of the system, three coordinate systems are chosen with origin at O 1, O 2, and O 3. The choice of these coordinate systems has some algebraic advantages. In the text, the subscripts k=1, 2, and 3 refer to the first portion, the second portion, and the third portion of the beam, respectively. For free vibration of the beam at frequency, if the amplitude of vibration of the beam is U zk (y k ) at axial coordinate >(y> k (in the range 0<y k <CR k L), then based on the Euler-Bernoulli bending theory, the bend-ing moment M xk (y k ), the shearing force Q zk (y k ), and the mode shape differential equation for the three portions are

To express these equations in dimensionless form, one defines the dimensionless axial coordinate Y k , amplitude Z k (Y k ), operator Dn, dimensionless bending moment M xk (Y k ), shearing force Q zk (Y k ), and a dimensionless natural frequency Ω as follows:

Therefore, Eq. (B1) can be expressed in the dimensionless form:

Consider the solution of the previous equation as

There are 12 unknown constants C ki (i=1, 2, 3, 4) for the three segments.

For free vibration the D’ force and moment acting on the left wheel is \(m_{\text{w}} \omega ^2 U_{z1} (R_1 L)\) and \(J_{\text{w}} \omega ^2 U^\prime_{z1} (R_1 L)\) respectively (Fig. B2). Continu-ity of deflection and continuity of slope at O wL together with compatibility of bending moments and compatibility of forces acting on the left wheel results in

The D’ force and moment acting on the left wheel is \(m_{\text{w}} \omega ^2 U_{z2} (R_2 L)\) and \(J_{\text{w}} \omega ^2 U^\prime_{z2} (R_2 L)\), respectively. Continuity of deflection and continuity of slope at O wR together with compati-bility of bending moments and compatibility of forces acting on the right wheel results in

Note that Eq. (B6) takes into account the contra di-rections of the axial coordinates y 2 and y 3. Eqs. (B5) and (B6) in di-mensionless form are

For the free boundary condition at the left end of the first portion and the right end of the third portion, the coefficients of the dimensionless mode shape functions satisfy

Then one can write the dimensionless mode shape functions of the first and third portions as

Substituting Eqs. (B10) and (B4) into Eqs. (B7), we can obtain:

Then one can write the dimensionless mode shape function of the second portions as

where

The coefficients of sin(α Y 2), cos(α Y 2), sinh(α Y 2), and cosh(α Y 2) in Eq. (B4) (when k=2) correspond to those in the expression obtained by substituting Eq. (B13) into Eq. (B12), so we can obtain

The coefficients of B 11 and B 12 in Eq. (B14) correspond to those in the expression by simplifying Eq. (B11), so we can obtain:

So far the mode shape functions of the second and third portions have four unknown constants in total. These four unknown constants can be calculated using Eq. (B8). The first two equations of Eq. (B8) can be written as

One considers

where

Using the last two equations of Eq. (B8), we can obtain:

where

Using the matrix form of Eq. (B20), one can obtain

Eq. (B22) is the frequency equation, which is a transcendental equation. By using an iterative procedure based on linear interpolation, the first three natural fre-quencies are f 1=111 Hz, f 2=245 Hz, and f 3=547 Hz, respectively.

The calculation of the coefficients of the three mode shape functions are demonstrated in detail in the fol-lowing.

The dimensionless mode shape functions can be written as

One may set the deflection of the first particle to be A and without loss of generality one may choose A=1, hence

From the above equation and Eq. (B20), one can obtain the following equations:

Subsequently, substituting the last equations into Eq. (B23) (assuming k=1) one can obtain the dimensionless mode shape function of the first portion \(Z_1 (Y_1 )\;(0 \leqslant Y_1 \leqslant R_1)\). Substituting Eq. (B25) into Eq. (B23) (assuming k=3) one can obtain the di-mensionless mode shape function of the third portion \(Z_3 (Y_3 )\;(0 \leqslant Y_3 \leqslant R_3)\). By inserting Eqs. (B15) and (B16) into Eq. (B4) (assuming k=2) one can obtain the dimensionless mode shape function of the second portion \(Z_2 (Y_2 )\;(0 \leqslant Y_2 \leqslant R_2)\).

Hence, the coefficient of the three mode shape functions can be calculated in Table B1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, Sq., Xiong, Jy., Xiao, Xb. et al. Effect of the first two wheelset bending modes on wheel-rail contact behavior. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 15, 984–1001 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.A1400199

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.A1400199

Key words

- High-speed railway vehicle

- Wheel-rail contact behavior

- Rigid wheelset

- Flexible wheelset

- Modal analysis

- Random track irregularity