Silent as it was, cinema in the early twentieth century spoke loudly on behalf of women’s rights. Two of the three major woman suffrage organizations took advantage of the fledgling medium to create films that would persuasively argue for women’s right to vote, and suffragist politics and rhetoric were frequently seen in popular cinema, particularly in the works of the female filmmakers who enjoyed a brief heyday during the 1910s.1 And at the turn of the twentieth century, a new channel for activist voices was badly needed. By that point, the suffrage movement had grown from its humble beginnings at the approximately three hundred-person Seneca Falls Convention to a national movement which had already succeeded in winning the right to vote in four states.2 However, it had also reached an impasse. From 1896 to 1910, no tangible progress was made in terms of legislation—a turn of events which has prompted some historians to brand this period “the doldrums.”3 Alternatively, historian Sara Hunter Graham has labeled this period “the suffrage renaissance”4—an altogether more appropriate term as, far from being idle during this period, the suffrage movement was busy reinventing itself. As the strength of the suffrage movement grew, however, so did the antisuffrage movement. “Antis” busied themselves creating propaganda that argued that women’s enfranchisement would be harmful to American society and attempted to discredit suffragists by attributing distorted, fringe, or simply ridiculous beliefs to the movement at large. Because of this reactionary element, changes in suffrage activism during this period were largely focused on rectifying the movement’s public image in the face of antisuffrage propaganda, such as the oft-repeated assertion that women were too emotional or too delicate to properly exercise the vote.5 What began as a public relations effort quickly turned into full-on advocacy for women’s right to vote; advocacy which expanded into new channels previously unused or underused by the suffrage movement. While suffragist organizations still largely focused on traditional methods of political outreach such as pamphlets and rallies, individual suffragists began to create a large number of plays, songs, and literary works that could promote their cause in terms that the general public might find more palatable than the direct and forceful rhetoric of political rallies and suffrage pamphlets. Such works aimed to provide suffragists with the attractive public face they needed to win over the male politicians and constituencies that represented the movement’s path to success. And in the final decade of their struggle for the vote, early twentieth century feminists found in the burgeoning medium of cinema a new and effective vehicle for their advocacy.

The connection between cinema and the suffrage movement is now well-established. Shelley Stamp, Maggie Hennefeld, and Kay Sloan have all published chapters on the intersection of cinema and suffrage, and Amy Shore has published a full-length book on the subject, in which she argues that the suffragist use of film “was one of the first instances in the United States that a social movement recognized and harnessed the power of cinema to transform consciousness and, in turn, transform the social order.”6 However, with the exception of Hennefeld’s chapter, which discusses the figure of the suffragette in slapstick comedy,7 most of these studies have focused primarily on films produced by suffragist organizations, and few give more than a brief nod to the suffragist rhetoric that can be found even in films that do not explicitly mention women’s struggle for the vote. Towards this end, therefore, this study will examine the narrative films produced by suffragist organizations (of which only one is extant) alongside a sample of the films produced by female filmmakers not employed by suffrage organizations in order to analyze the different rhetorics used by filmmakers of the time to argue for women’s rights, including the right to vote. Because an extensive analysis of films by American women filmmakers during the 1910s is beyond the scope of this paper, I will focus instead on two films by actress-director Cleo Madison—Her Defiance and Eleanor’s Catch (both 1916)—which I believe are particularly illuminating when considering the ways that suffragist rhetoric and the concerns of the suffrage movement may be found even in films that are not explicitly political.

In their depictions of women, pro-suffrage films generally sought to emphasize three traits: capability, femininity, and responsibility. An emphasis on women’s capability argued that they were equal to men in their ability to function in the public sphere. This was perhaps the most radical point, as the dominant ideology of separate spheres posited that women were only suited to operate in the domestic sphere and not the public sphere, assumed to be men’s domain. It was also arguably the most important point because it effected the most significant change: the expansion of the public sphere to include women. Emphasizing women’s femininity, even as they operated in the public sphere, was nearly as important, as it demonstrated that political participation would not turn women into the grotesquely masculine caricatures so often seen in antisuffragist propaganda.8 And highlighting their responsibility assured audience members that women, once given the vote, would use it for the betterment of society and not solely for their own interests. This last point, known as the “expediency argument,” is perhaps the most rhetorically complex strategy used by the suffrage movement as it relied heavily on Victorian ideas of gender which posited that women possessed a moral superiority that stemmed from their confinement to the domestic sphere, away from the corrupting influences of public life.9 This was also known as “civic housekeeping”—a seemingly natural extension of women’s role in the domestic sphere to the public sphere.10 Despite these reactionary undertones, the expediency argument has often been credited with the ultimate success of the suffrage movement as it was more palatable to the general populace than rhetoric that relied on women’s “natural rights.”11 That said, civic housekeeping’s connection to conservative gender roles often led more radical activists to eschew any reference to responsibility and instead base their arguments solely on women’s capability to act independently within the public sphere without losing their femininity. This will be reflected in my analysis, which will focus on these three qualities and how their cinematic depictions were fitted into and contributed to the cultural conversation around women’s suffrage.

The first section of my paper will provide a historical background on the use of popular culture to argue for women’s rights before the suffrage movement began to produce films. The second section will examine the narrative films made by the suffrage movement, focusing primarily on What 80 Million Women Want (1913), the only known extant example of these films.12 (The remainder of the movement’s films, like the majority of films from the silent era, are presumed lost.) Finally, the third section will examine the two complete extant films of Cleo Madison, dubbed “the lovely but militant Cleo” by a Photoplay Magazine writer due to her suffrage advocacy.13 In the conclusion, I will argue that Madison’s films, made outside of the suffrage movement’s control, put forward less direct but ultimately more radical arguments for women’s rights than the films produced by the public-image-conscious suffrage organizations. Both Her Defiance and Eleanor’s Catch deal with issues key to the suffrage movement’s advocacy but ultimately go beyond the relatively cautious positions that the suffrage organizations were willing to take. In this way, they embody the spirit, if not the letter, of suffrage activism to advocate for a wide-ranging view of women’s rights that began, not ended, with winning the right to vote.

What 80 Million Women Want: The Suffrage Movement Discovers Popular Culture

While pro-suffrage messages appeared in American popular culture just four years after the Seneca Falls convention,14 during the suffrage renaissance, plays, songs, and literary works advocating for women’s right to vote, most written by women, began to appear in much greater quantities.15 Suffragist leaders generally viewed these works in a favorable light, echoing the sentiments that the pioneering suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton expressed in her preface to Helen H. Gardener’s feminist novel, Pray You, Sir, Whose Daughter?, that “the wrongs of society can be more deeply impressed on a large class of readers in the form of fiction than by essays, sermons, or the facts of science.”16 Stanton, in this same preface, further expressed her desire for a work of fiction that would have an effect on public opinion concerning suffrage comparable to the effect that Uncle Tom’s Cabin had on public opinion concerning abolition.17 And while none of the pro-suffrage works garnered the lasting cultural status of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, they appear to have had an appreciably positive effect on popular support for the movement.

The most significant pro-suffrage cultural productions (at least before the advent of cinema) were the suffrage plays. These ranged from one-act “parlor dramas,” rarely intended to be staged professionally, to spectacular productions with full casts and ambitious settings. Bourgeois suffragists from the eastern United States (US) were initially suspicious of any attempt to blend their cause with theater, which they viewed as frivolous, if not morally corrupt. However, suffragists in the western states had no such inhibitions and were eager to dramatize the suffrage struggle for a mass audience. They experienced such great success in converting the public to their cause that even the most puritanical of the eastern suffragists were forced to take notice. By the mid-1900s, pro-suffrage plays had become popular nationwide.18 Suffragists praised their ability to attract spectators who were “fond of the drama and somewhat less fond of debate,”19 thus delivering the movement’s message not only to devoted suffragists but also to the general public: men and women who otherwise might never attend any kind of pro-suffrage event. Suffrage plays “could succeed where rhetoric had failed” by portraying their heroines as attractive, capable women whose femininity was unquestionable and whose commitment to the cause, however unshakeable, did not interfere with their personal relationships—at least once the object of their affection converted to the suffrage cause.20 The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) even credited the success of the suffrage campaign in California to the performance of suffrage plays, noting that they were particularly effective in converting public opinion in rural districts where entertainment options were few and large-scale political rallies unworkable.21 And while the suffrage plays proved effective political tools, just one year after California officially extended the franchise to women, another form of pro-suffrage entertainment—one even more accessible and attractive to the general population—would make its way onto the American cultural landscape: the suffrage film.

The suffrage renaissance corresponded very closely to the rise of cinema as both an art form and a form of popular entertainment. Through the pioneering efforts of film scholars such as Shelley Stamp, Jane M. Gaines, and Anthony Slide, it has become clear that women were involved in the film industry from its beginnings, and not only as actresses. In fact, according to a contributor to the Motion Picture Supplement, in 1915 there was hardly “a single vocation in either the artistic or the business side … in which women are not conspicuously engaged,”22 and in recent years the Women Film Pioneers Project (an online database founded by Jane Gaines and dedicated to scholarship on women in silent film) has identified a vast range of careers held by women within silent film industries worldwide. Furthermore, women are presumed to have formed the majority of cinema audiences from 1911 on, if not before.23 The result of this heavy involvement of women as both consumers and producers of film was that silent films often reflected a distinctly female perspective and played towards female tastes which, particularly in the 1910s, went far beyond the family or romance-based “tearjerkers” so frequently associated with female filmgoers. Filmmakers of both sexes also produced films that sympathetically viewed the plight of women in society, advocated for their rights, and portrayed them as strong, active figures capable of doing anything a man could do, given the opportunity.

Many prominent suffragists initially regarded cinema in much the same light that they first saw the theater: as a frivolous amusement of no meaningful political application. NAWSA president Anna Howard Shaw, among other reformers, even regarded the cinema as harmful to society, referring to movie theaters as “recruiting stations of vice.”24 Here, however, the paradigm shift that would convince skeptical suffragists of the power of cinema did not come in the form of a pro-suffrage drama; it came in the form of a newsreel. In 1912, NAWSA organized a massive march down Fifth Avenue in New York. While the conservative element in the suffrage movement considered it scandalous to occupy the public sphere to this degree, the more progressive suffragists saw in the parade an opportunity “to transform the perceived threat of women’s political power into a visual spectacle of moral heroism and beauty.”25 Not only was the march a local success, it was caught on camera by the Special Event Film Company and included in a newsreel which became the first true-to-life cinematic representation of the American suffrage movement.26 This newsreel, though not the first to depict the movement, was the first to resist the urge to sensationalize it.27 By accurately representing the movement, the newsreel gave it credence and portrayed its members as strong, dignified women fighting for a just cause. Furthermore, because it could be viewed by a national audience almost simultaneously, it was able to provide an organized view of the suffrage movement as it really was, in a format that was far more wide-reaching than even the suffrage plays.

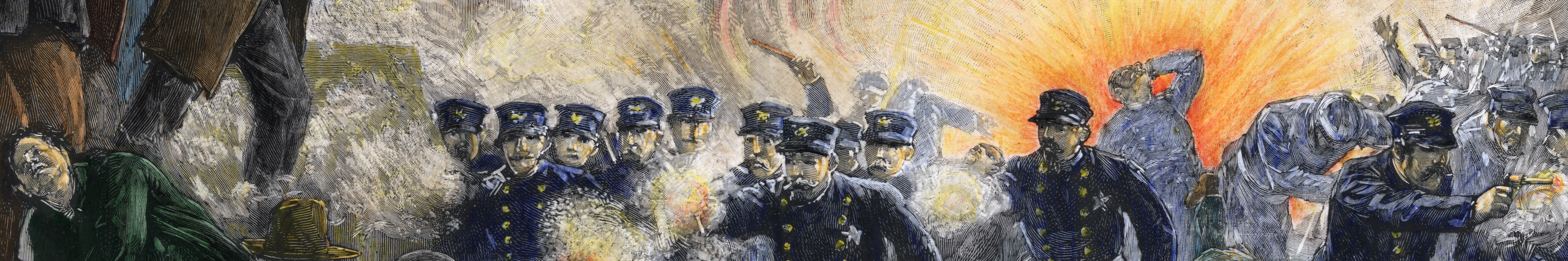

This newsreel was far from the first time suffragists had been depicted in cinema. However, before 1912, virtually all films dealing with suffrage were derisive comedies which portrayed suffragists in an almost entirely negative light. Many of these early comedies were produced in England, where the militant tactics of suffragists such as Emmeline Pankhurst shocked the public and became the subjects of ridicule in films such as The Lady Barber (G. A. Smith, 1898), in which a suffragist commandeers a man’s barber shop and proceeds, Delilah-like, to butcher the hair of any man unfortunate enough to cross her path.28 These English titles were imported to the US (a common practice in early cinema that, as Tom Gunning has noted, “was international before it was national”29) and influenced early American comedies such as A Lively Affair (Edison, 1912) which, like The Lady Barber, portrayed suffragists as aggressive, combative, and often grotesquely masculine. These caricatured women were often willing to engage in physical violence at the slightest provocation from the beleaguered men who surrounded them. The Edison Company’s How They Got the Vote (1913) took this trope one step further, depicting its main character, a suffragist, holding such a hatred of men that she sabotages her own daughter’s engagement.30 Still other films took the idea of the man-hating suffragist even further by intimating that suffragists, rather than seeking gender parity, sought to create an oppressive matriarchy that would replace the existing patriarchal order and force men into subordinate roles.31 Although these films “remain open to alternative readings and feminist appropriation,” as Maggie Hennefeld points out, it is important to acknowledge that, at the time of their production, they were “deeply complicit in thwarting crucial [suffragist] claims.”32 Through their caricatured depictions of suffrage activists, slapstick comedies played directly into the hands of antisuffragists and set a precedent for the cinematic treatment of suffragists that organizations such as NAWSA and the Women’s Political Union (WPU, NAWSA’s more radical rival) were eager to disrupt.

While there had been some small-scale attempts at using cinema to promote suffrage before 1912,33 the Fifth Avenue March newsreel demonstrated that cinematic depictions of suffragists could be accurate representations of the movement which might not only empower individuals already committed to the cause, but also convert both men and women to the movement’s ideals. The newsreel was so successful that it became a cinematic symbol for the suffrage movement, used as stock footage in so many films (both pro- and anti-suffrage) that by the time the movement produced its last film in 1914, the use of the footage had become hackneyed to the point that it was a selling point for that film that it did not include “the familiar suffrage parade.”34 After the newsreel’s release, suffragists were eager to take advantage of cinema to create new and empowering visions of the movement to inspire activists and “appease the public anxiety” concerning the issue of suffrage by demonstrating to filmgoers that they were not the violent man-haters that antisuffrage comedies depicted them as.35 Ironically, given the number of comedies that mocked suffragists, the first suffrage film made under the auspices of the movement was itself a one-reel comedy: Suffrage and the Man, produced in 1912 by the Eclair Company and overseen by the WPU. The film depicts the misadventures of an antisuffragist who ends his engagement with a suffragist after learning of her political views. Sometime later, after the suffrage battle has been won and women granted the right to vote, he is sued by a jealous woman, but is ultimately acquitted by a sexually integrated jury headed by his former sweetheart. Finally admitting defeat and the falsity of his former values, he pledges his support for women’s liberation and wins back his old love.36 NAWSA quickly responded with a short film of their own, entitled simply Votes for Women (1913). Unlike Suffrage and the Man, Votes for Women was a serious drama featuring performances by suffragist leaders Anna Howard Shaw and Jane Addams. Judging by contemporary reviews published in motion picture trade journals such as the Moving Picture World, both of these films appear to have been generally well-received by critics and audiences alike,37 and their successes would inspire the suffrage movement to take on an even greater challenge: the production of a four-reel feature film.

That film, entitled What 80 Million Women Want, was released in 1913 by the Unique Film Company and is the only film produced by the suffrage movement that is still known to exist.38 The screenplay was written by suffragist Florence Maule Cooley and screenwriter B. P. Schulberg, better known for writing the 1914 Mary Pickford vehicle Tess of the Storm Country. The film’s narrative is essentially a simple melodrama of romance and political corruption in which Mabel, a suffragist, fights to reform the municipal government of New York City, which is under the control of the corrupt Boss John Kelly. In the film, Boss Kelly plots to rig the upcoming election to stay in power, and controls the city courts to the point where he can acquit any of his cronies if they are accused of a crime. This political control is demonstrated early in the film when Boss Kelly forces the judge to drop the charges after one of his cronies severely injures a young clerk in a hit-and-run, and as Robert Travers, a struggling young lawyer and Mabel’s sweetheart, is forced to join Boss Kelly in order to stay in business. Mabel, already frustrated with his refusal to support the suffrage cause, ends her relationship with Robert when she learns that he has acquiesced to corruption. Broken-hearted, Robert severs his ties with Boss Kelly and begins to gather evidence against him with the help of a suffragist who has been hired as the latter’s personal secretary, infiltrating and undermining his organization at the behest of the WPU. The film climaxes during the election, in which Boss Kelly, despite his attempts at electoral fraud, is defeated and an amendment to the state constitution passes to give women the vote. Finally, Mabel and Robert are reconciled and the film ends as Robert presents Mabel with a marriage license.

As Vachel Lindsay contended in his seminal monograph The Art of the Moving Picture, suffrage films couched their messages “amid the sweetness and flowers … of the photoplay story.”39 This film clearly demonstrates that idea, as it frames its controversial argument for suffrage within a more commonplace story. Much has been written about the ways in which suffrage films used romance to situate suffrage within a nonthreatening framework through an emphasis on the suffragists’ femininity. Kay Sloan writes that “beautiful suffragist heroines who combined political activity with romantic and family interests” showed that suffrage was not incompatible with romantic love or peaceful coexistence between the sexes.40 Indeed, all four suffrage films include romance, and What 80 Million Women Want emphasizes it to a degree in its ending in which Robert presents Mabel with a marriage license. However, the sparse attention the film gives to the romance before this point prompts one to ask the question: “is marriage What Eighty Million Women Want–?, or is the right of suffrage What Eighty Million Women Want?”41 While some scholars have seen this as undermining the films’ feminist messages by centering the women’s narratives on their relationships with men,42 these elements were included in order to counteract the stereotype of the man-hating suffragist, not to deprive the female characters of their agency. To do so would be antithetical to the purpose of the suffrage films. Any film that advocates woman suffrage will, in one way or another, make the case that women are capable of exercising responsible, effective public agency. Thus, to deprive a female character of her agency would render this argument moot. A film might advance the argument that women are capable of exercising this form of agency, but if it were to focus on romance to the exclusion of scenes depicting women’s political activity, it would not be a persuasive piece of pro-suffrage visual rhetoric.

If a film can be said to be successful in making an argument for women’s right to vote by portraying its female protagonist(s) exercising responsible, effective public agency, What 80 Million Women Want was a great success. Mabel is shown to be equally as capable as the male characters in the film, and perhaps more intelligent than any of them. She is an outspoken suffragist who attracts massive crowds with her speeches, demonstrating the effectiveness of her ability to utilize the public sphere, and is able to use her wits to discover valuable evidence against Boss Kelly and his cronies. She does this detective work almost entirely on her own, further demonstrating her intelligence and agency. Moreover, her romance with Robert does not blunt her dedication to her cause. She is not willing to compromise her values to be with Robert and ends their relationship when she discovers that he has become part of Boss Kelly’s organization. And when the sweetheart of a fellow suffragist is arrested for attempting to assassinate Boss Kelly, Mabel encourages her to forget him and shores up her dedication to the cause, telling her “[w]e must fight for right.” There is little question that Mabel loves Robert, but their romance is such a minor part of the story that it functions mainly as a bromide to soothe the ire of viewers not yet fully sympathetic to suffrage. This mainstream story element assists rather than impedes the delivery of the film’s message as it seeks to avoid polarizing the audience before the film can make its point. The suffrage debate was well-worn by this point, and many viewers—particularly those who were ambivalent towards the cause—were tiring of it.43 Many of these ambivalent viewers were male voters who could, in states that had not already passed suffrage bills, vote for pro-suffrage candidates (or against antisuffrage candidates) and thus directly impact the cause for women’s rights. These men were generally the hardest converts since many of them had been inundated with antisuffrage propaganda. However, as one contemporary reviewer wrote,

People who will not listen to a lecture on suffrage … will not object to a little suffrage mixed judiciously with a great deal of heart interest. Gradually, their minds will follow their hearts. Soon they will accept the doctrine as a matter of course and wonder why anybody should cavil at it.44

While the film could be seen as purer in its feminist message if it did not include the “sweetness and flowers” that Lindsay describes, it is unlikely that audiences would have been as eager to see it and thus fewer people would have heard its argument in favor of women’s suffrage.

With this strategy, What 80 Million Women Want continues the rhetorical traditions that the movement had developed for use in its day-to-day advocacy. Chief among these is the civic housekeeping argument, emphasizing the notion that women should be granted the right to vote not out of their natural rights as human beings but, rather, because they would use their voting power to reform society along more ethical lines.45 The narrative of political corruption fits neatly into this discourse. Boss Kelly opposes women’s right to vote because he believes that, if women were allowed to vote, they would pose a danger to his power: a perspective that the film ultimately supports as Mabel and her fellow suffragists thwart his plan to rig the election and see him convicted for corruption. Because cinematic arguments in favor of civic housekeeping involved women’s active participation in the public sphere and emphasized their capability to participate, they cannot be said to be fully conservative. However, they do take advantage of the Victorian view of women as morally superior guardians of the social status quo.46 For instance, in What 80 Million Women Want, Robert’s eventual acceptance of Boss Kelly’s offer of political favors implies the inherent corruptibility of men in political office. When contrasted with the women’s moral steadfastness, this creates a strong argument for women’s participation in politics that relies on the idea of women as inherently more responsible than men. These conservative undertones do not invalidate the film’s advocacy or blunt its impact—the expediency argument is often credited with the growth of public support for the suffrage movement which occurred during the suffrage renaissance47—but it is important to take note of them and realize that while suffrage films were willing to take a direct stand on one of the most controversial women’s issues of the early twentieth century, their views on gender roles were in reality more conservative than they might initially seem.

“Lovely, But Militant”: Women’s Rights and the Films of Cleo Madison

Different films, much like different suffrage organizations, used varying strategies to win over their viewers. Amy Shore writes that while some suffrage organizations used relatively conservative strategies, such as the civic housekeeping argument, “others invoked women’s status as self-supporting women … to claim their right to the vote not as an extension of their domestic role but as an acknowledgement of their full participation in the public sphere.”48 While the films made by the suffrage movement tended towards more conservative arguments for extending the franchise, other films engaged head-on with the idea of the New Woman: women liberated from archaic gender roles, capable of doing virtually anything a man could do and, therefore, deserving of full and equal social and political rights. It is into this category that the two complete surviving films of director Cleo Madison fall. These two films, Her Defiance and Eleanor’s Catch, posit that beneath women’s façade of domesticity lies the potential for a true equality that would benefit both men and women. This is more or less subtextual in both films, but it is ultimately a more radical argument for women’s equality (including the right to suffrage) than the films produced by the suffrage movement since Madison’s films emphasize women’s capability to operate in the public sphere—a capability that brings with it the right to enfranchisement—more than the responsibility they would be expected to operate with if given the opportunity.

Madison began her career as an actress and scriptwriter for Universal Pictures before becoming a director for the same studio. But while her role at Universal changed frequently, one thing remained consistent: Madison always imbued her work with a feminist sensibility driven by her own political interests, which included an interest in suffrage that caused her to be referred to as “the lovely but militant Cleo” in a contemporary article on her work.49 As a director, however, she took this sensibility beyond the realm of subtext to create films which cleverly invert audience expectations so that films which initially seem to depict their heroines’ victimization ultimately place all of the agency for narrative resolution in their hands and demonstrate how capable these women are of using it. In my analysis, I will focus primarily on the narratives of the films themselves. Although extratextual materials such as promotional images and press releases can reveal a great deal about a film, in the case of these two titles, I found not only that these materials are thin on the ground but also that they reveal very little about the films’ connection to the suffrage movement.

Her Defiance, the earlier of the two films,50 clearly demonstrates the inability of family life to solve working-class women’s problems, making its feminist message palatable by couching it within a relatively conventional melodrama of romantic misunderstanding. Adeline (played by Madison herself), a young woman living in a small town, meets and falls in love with Frank Warren, a visiting businessman of whom her domineering father and brother disapprove, as they are scheming to marry her off to the richest man in town. The two lovers meet in private and, unbeknownst to either of them until much later, Adeline becomes pregnant. Frank is unexpectedly called back to the city and must leave without saying goodbye to Adeline. Instead, he writes her a letter which he unwisely entrusts to her brother, who destroys it. Despondent and now realizing that she is pregnant, Adeline agrees to the marriage arranged by her family but runs away at the end of the ceremony. Her ersatz husband chases her but crashes his car and is killed while she escapes. Back in the city, Frank receives word of Adeline’s marriage, but not of the death of her husband, and is devastated by the news. Approximately a year later, Adeline is living in the city and makes a living for herself and her newborn son by cleaning an office building, which happens to be the one where Frank works. He goes into his office during the night and hears Adeline’s baby crying in a broom closet. Fearing that the child has been abandoned, Frank brings him into his office, where he is discovered by a furious Adeline who believes that Frank had abandoned her. Blindsided, he explains the miscommunication (in an innovative split-screen flashback) and ultimately the two are reconciled, for “when a woman loves, she forgives.”

At first glance, Her Defiance may not seem to be a particularly feminist film, especially in comparison to the explicitly political films produced by NAWSA or the WPU. Its narrative appears to be one of female victimhood and powerlessness which is only tempered, Cinderella-like, by the happy ending provided by heterosexual romance. Ultimately, however, the film demonstrates Madison’s gift for reversing audience expectations and empowering seemingly disempowered characters. Even the film’s title speaks to this empowerment and Adeline’s steadfast refusal to allow anyone else to control her life. She prominently exercises this agency several times in the film: most notably when she runs away from the arranged marriage and when she elects to forgive Frank at the end of the film. This last point might not seem particularly feminist, but in the context of a romantic melodrama in 1916, to give the woman, and not the man, the power to forgive or not to forgive, to marry or not to marry, can easily be seen as a feminist statement. In the reconciliation scene, Frank is ultimately in Adeline’s power as she threatens to make sure that their son never knows him, and as she understands that he was another victim of her family’s machinations, she forgives him. The couple’s love wins out, but only because Adeline wills it to be so. Furthermore, Adeline’s anger in this scene makes it clear that this forgiveness was not guaranteed and that if Frank did not have an acceptable explanation, she would have made good on her threat to deny him the opportunity to know their son.

The most notable feature of this film in relation to the suffrage movement is its treatment of marriage and family. A common antisuffrage argument was that domesticity in any form, including in an abusive relationship, was better for women than participation in the public sphere.51 Her Defiance takes the opposite tack to argue that there are some forms of family that are worse than having no family at all. The example the film provides is Adeline’s bleak life with her father and brother. They seem to regard her as little more than a slave, evidenced not only by the amount of work they force her to do but also by the fact that they view her as a commodity to be bought and sold. The arranged marriage they coerce her into is utterly mercenary as the man they are marrying her off to is both the richest and oldest man in town. The men’s scheme can be inferred as having Adeline marry him and, when he dies, to take possession of his property. At that point, they can then legally take control of it, as a woman’s property was legally deemed to belong to her closest male relative. This was a major issue for the suffrage movement, who used it as the basis of their final film, Your Girl and Mine (1914),52 and while Her Defiance only indirectly touches on it, its position on the issue is very clear as Adeline’s male family members are depicted as scheming, abusive, and thoroughly unsympathetic. While Adeline is not depicted as particularly well-off after fleeing to the city, she is perfectly capable of surviving and certainly less tortured than she was with her family, clearly demonstrating that domesticity cannot be said to be the only solution, or even the best solution, to women’s problems.

Furthermore, the film takes a forceful stance on the issue of arranged marriage. It is clear that Adeline is not responsible for the situation that she finds herself in: that she is the victim of her scheming family and lecherous suitor. The only reason that she agrees to go through with the wedding in the first place is that she is “afraid of the world’s verdict” once she discovers that she is pregnant out of wedlock. (That phrase, taken directly from the film’s intertitles, is in and of itself a feminist statement, as it implies that premarital sex and single motherhood are not inherently wrong, simply that they have been deemed so by society.) Madison clearly views arranged marriages as a criminal form of bondage in which women are allowed to be essentially bought and sold against their wills. The death of Adeline’s ersatz husband, therefore, becomes a form of punishment for participating in this crime. He crashes his car while chasing after Adeline in an attempt to bring her back and force her to stay with him. In this way, he is essentially killed by his own attempt to exert control over Adeline’s life.

While the film is critical of the idea of domesticity as the ultimate solution for the problems of women, it is not anti-family as a general principle; it is simply against the idea that any family, even an abusive one, is better for women than no family at all. This is clearly evidenced by the film’s treatment of Frank. Miscommunications notwithstanding, Adeline’s relationship with Frank is a mutually loving companionate relationship and is coded as such from their first meeting. When Adeline’s grocery bag breaks as she leaves the store, Frank helps her pick up her groceries and makes friendly, respectful conversation while the other men in the scene stand by and watch, unwilling to offer her any help. This might be seen as a typical romance-film “meet-cute” with no further significance were Frank not the only man in the film who treats Adeline as a human being, especially as compared with her family’s mercenary attitude towards her. Furthermore, throughout the film, it is Frank who must prove himself worthy of Adeline’s love, not the other way around as in so many other silent romance films, and it is the respect with which Frank treats Adeline throughout the film that marks him as worthy. In this way, the romance in Her Defiance is similar to the romances in the suffrage films as it depicts mutual respect as the foundation of a romantic relationship, shows men, by and large, to be the ones who must learn that respect, and couches its social critique in the “sweetness and flowers” of an uplifting romantic story. Finally, despite being grounded in early twentieth-century women’s oppressive realities, the film ultimately empowers its heroine in a way which suggests a path forward into a world in which the personal and societal needs of both men and women can be satisfied.

In contrast to the relatively subtle rhetoric of Her Defiance, Madison’s other surviving film, Eleanor’s Catch, takes a far more forceful tack towards depicting women’s capability for a responsible, effective exercise of agency in the public sphere. The film opens as an impoverished Eleanor McGrady (again played by Madison) receives a visit from Flash Dacy, the neighborhood gangster, whom we later learn has kidnapped Eleanor’s sister and turned her into “a forgotten thing of the shadows” by forcing her into prostitution. Dacy begins to court Eleanor by offering to pay the bills for her and her mother. She accepts, much to the chagrin of her sweetheart, Red, and over the course of the next few weeks, Dacy brings her further and further into his criminal enterprise. He teaches her how to steal by faking a yawn and stretching to remove valuables from people’s pockets. She is almost comically bad at it. Finally, intending to give her a practical lesson, Dacy lures an intoxicated man into Eleanor’s home so that she can steal from him: tempting the man, it is implied, by prostituting Eleanor. She appears to reluctantly follow his direction, faking a yawn and stretching her arms in both directions towards Dacy and the stranger. However, instead of stealing the stranger’s wallet, she grabs Dacy’s gun—her demeanor changing in a split second—and holds him at gunpoint, revealing herself to be a Secret Service agent operating undercover to capture Dacy. He attempts to overpower her, but as they fight on the floor, Red and Eleanor’s mother return with a police officer who arrests Dacy and returns Eleanor’s sister to the care of her family.

The most important element of suffragist discourse that Eleanor’s Catch engages with is the question of the place of women in the public versus the domestic sphere. It does not seem too much of a stretch to argue, as the notes for the film’s first DVD release do, that the revelation that Eleanor has been a Secret Service agent the entire film makes a strikingly powerful case for women’s capability in the workplace.53 However, there are subtleties here that deserve unpacking. The film’s epilogue, set in the happy home that Eleanor has created by rescuing her sister, is heralded by a title that reads, “Having run down her last case, Eleanor returns to her home life.” Taken at face value, this title would seem to undercut the film’s argument by implying that regardless of their participation in public life, women’s eventual destination is the home. This can be seen as a form of the expediency argument in that the image of the public-minded woman that it conjures is one of a woman who uses her activity in the public sphere to improve the social status quo in the form of the male-headed nuclear family, to which she then happily returns. However, in his chapter on Eleanor’s Catch, Mark Garrett Cooper notes that “this hasty conclusion cannot help but raise the question of how we can be certain that this really is Eleanor’s last case.”54 This becomes an especially pertinent question when we realize that Eleanor-the-domestic-woman’s family is also Eleanor-the-secret-agent’s team. In this way the film leads its viewer towards a reimagining of family in which each person is an equal member of a team: “pals,” as famed action film star and “serial queen” Pearl White put it,55 rather than master and servant. Such redefinitions of family were key to suffrage rhetoric as activists fought against antisuffragists’ fetishization of the traditional home (complete with the submission of the wife to the will of the husband) by arguing that families should be built on mutual respect and cooperation rather than outmoded gender hierarchies.56

While the argument that Madison presents in Eleanor’s Catch is very different from the one in Her Defiance, there is a notable commonality between the two films: both take an established cinematic archetype and use it to make a case for women’s rights by placing far more agency into the heroine’s hands than is called for by that archetype. In the case of Eleanor’s Catch, the archetype is not the Cinderella story or the romantic melodrama but the white slave film. Shelley Stamp writes that these films frequently seem to be intended to frighten women away from participation in public life by showing women who venture into the public sphere being victimized by men who then sell them into prostitution (“white slave” being an archaic and racially loaded term for a woman forced into prostitution).57 Although the film makes no explicit reference to prostitution, as this would have made the film a target for censorship, it would have been clear to a contemporary audience familiar with the tropes of the white slave films, which had been extremely popular before they attracted the attention of censors.58

In terms of its feminist message, the two most significant aspects of Eleanor’s Catch in relation to the white slave film are its use of the public sphere and the figure of the male rescuer. In the white slave films, women who enter the public sphere are generally coded as vulnerable and in need of protection or rescue by a male hero, even if, as in the pessimistic The Inside of the White Slave Traffic (1913), that rescue never comes.59 Until the climactic fight between Eleanor and Dacy, Eleanor’s Catch appears to fall into this paradigm: the only time Eleanor is seen outside of her family’s home is when Dacy takes her on a date and attempts to turn her towards a life of crime, and when Red finds Eleanor’s sister wandering the streets, the film appears to imply that he will be the one to rescue Eleanor from sharing a similar fate. However, in its ending, the film turns the white slave paradigm upside-down. Most evidently, Eleanor needs no rescuing. Red and the police may come in at the very end of the fight between Eleanor and Dacy, but it is Eleanor who steals his gun, Eleanor who fights hand-to-hand with the criminal, and Eleanor’s supposedly “forgotten” prostituted sister who picks up the gun when it is dropped and uses it to make a valiant, if unsuccessful attempt, to stop Dacy, the architect of her exploitation, from attacking Eleanor. When Red arrives, his role is important, but ultimately close to an afterthought, only marginal to the scene’s central actions. Furthermore, the film gives little indication that Red is anything but satisfied with this marginal role. This mirrors the real-life efforts of men who fought alongside female suffragists in the struggle for the women’s right to vote. Male voters and activists played an important part in the battle for suffrage, particularly in New York, but were content to play this part from the background, emerging only when their political or social clout was needed.60 Taking this connection, the film’s concern with patriarchal exploitation of women, and the centrality of the female action hero into account, Eleanor’s Catch may be seen as arguing that liberating women from patriarchy is chiefly women’s work: while men’s help is needed and important, the best results will always come when women take the lead in deciding their own destinies.

However, the disclosure of Eleanor’s identity reveals something even more radical: while the film had previously implied that she had led a largely domestic existence, in fact, as a secret agent, every situation we have seen her in is in a certain sense the public sphere. Far from being bound to the home, she is on the job for virtually the entire film. In fact, as we see in the film’s final scene, which shows Eleanor’s family reunited after she apprehends Dacy and rescues her sister, neither of the “homes” in which we have previously seen Eleanor are actually her home. Instead, they are her workplaces, and Eleanor, rather than occupying the role of the helpless homebound woman, is portrayed as such a skilled agent that she is capable of fooling not only Dacy but the audience as well.

Finally, much like Her Defiance, Eleanor’s Catch deals with a subject that was explicitly invoked by suffrage activists. In 1912, NAWSA published a pamphlet written by Chicago prosecutor Clifford G. Roe entitled What Women Might Do With the Ballot: The Abolition of the White Slave Traffic. In that pamphlet, Roe lays out a number of ways in which women’s enfranchisement and participation in political life would aid in the battle against sex trafficking. It is Roe’s view, at least to an extent, that dismantling white slavery criminal rings is a job best carried out by women.61 And while Eleanor fights sex traffickers as a secret agent rather than a voter, her capability in doing so, even within the melodramatized framework of Madison’s film, is easily extrapolated to a real-life context: if one woman can almost singlehandedly capture a white slaver, imagine what women as a group could accomplish in the fight against “the social evil” if only they were given the right to vote.

Conclusion: On to Victory

It has been the objective of this paper to examine the intersection of cinema and the woman suffrage movement, not only in the small number of explicitly suffrage-centered films, but also in a small sample of the many films whose concerns intersected with the suffrage movement and its rhetoric. In examining these films, it becomes clear that public-image-conscious suffrage organizations were largely unwilling to use their films to take radical stances on the prevailing women’s issues of the time. Because of this, they generally limited the films they had direct control over to relatively conservative pro-suffrage arguments which were centered on women’s responsibility in exercising political power—an exercise of power that is depicted as largely beneficial to the status quo. However, the two extant films of the “lovely but militant” Cleo Madison tell a different story. While they never mention suffrage by name, the issues they deal with—such as forced marriages, sex trafficking, and the nature of gender relations within romantic relationships and the family—were frequently key points in suffrage advocacy. And since Madison was not explicitly speaking on behalf of the suffrage movement, she did not need to preserve a decorous public image and could make much more radical assertions about women’s positions in society, arguing in both Her Defiance and Eleanor’s Catch that women possess the capability to participate in public life with or without a man by their side, and furthermore that this participation, far from being detrimental, has the potential to rescue men and women alike from the oppressive clutches of patriarchy. Moreover, in Madison’s films, this participation in public life is depicted as a completely normal part of women’s lives, not the masculinizing perversion of nature that antisuffragists claimed it would be. While such analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, it is also worth noting that Cleo Madison was one of many women filmmakers producing socially conscious films during the 1910s, and that the films made by women such as Ida May Park and Lois Weber may well be just as worthy of examination alongside the suffrage movement.

To examine these films as part of the feminist cultural conversation around suffrage is to consider the ways in which discourses on social and political issues can escape the boundaries of the established political sphere and cross over into the sphere of popular entertainment, and to further consider their efficacy outside of the traditional political sphere. Whether the issue at hand was women’s right to vote, to work outside the home, or to be free from abusive surroundings and the limits of traditional domesticity, filmmakers during the early twentieth century were able to make their voices heard throughout the nation in ways that could resonate with politically diverse audiences, ultimately strengthening rather than diluting their rhetoric by ensuring that their voices—silent as they were—were heard.

Notes

- The term “suffragist,” though potentially unfamiliar to contemporary readers, was the preferred term used by suffragists to refer to themselves, as the more recognizable term “suffragette” was not only gendered, excluding male supporters of suffrage, but frequently used derogatorily.

- Olivia Coolidge, Women’s Rights: The Suffrage Movement in America, 1848-1920 (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1966), 9-12.

- Eleanor Flexner and Ellen Fitzpatrick, Century of Struggle: The Women’s Movement in the United States, (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996), 241.

- Sara Hunter Graham, Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 33.

- Aileen S. Kraditor, The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890-1920 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), 18-20.

- Amy Shore, Suffrage and the Silver Screen (New York; Peter Lang, 2014), 1.

- Maggie Hennefeld, Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 173.

- Kraditor, Ideas of Woman Suffrage, 36.

- Ibid., 22.

- Jane Addams, Newer Ideals of Peace (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1906), 181-183.

- Holly J. McCammon, “Stirring Up Suffrage Sentiment: The Formation of the State Woman Suffrage Organizations, 1866-1914,” Social Forces 80, no. 2 (December 2001): 460-461.

- There are other extant films dealing directly with the issue of suffrage—for instance, Mothers of Men (1917)—but these films were not produced with the direct involvement of suffragist organizations.

- William M. Henry, “Cleo, the Craftswoman,” Photoplay Magazine, January 9, 1916, 109.

- The earliest example I have been able to find on this is a piece of sheet music entitled “The Great Convention, or Woman’s Rights,” published in 1852 and included in Danny O. Crew, Suffragist Sheet Music (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002), 33.

- For more information on suffrage activism in music and drama, and for examples of suffrage songs and plays, see Francie Wolff, Give the Ballot to the Mothers: Songs of the Suffragists; A History in Song (Springfield, MO: Denlinger’s Publishers, 1998), xv; Sheila Stowell, A Stage of Their Own: Feminist Playwrights of the Suffrage Era (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992), 40.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, preface to Pray You, Sir, Whose Daughter?, by Helen H. Gardener (Boston, 1892), vi.

- Ibid., vi-vii.

- Bettina Friedl, introduction to On to Victory: Propaganda Plays of the Woman Suffrage Movement, edited by Friedl (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1987), 6-7.

- “Suffrage Play,” The Suffragist, December 20, 1913, 48.

- Kay Sloan, The Loud Silents: Origins of the Social Problem Film (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 109.

- Ibid.

- Robert Grau, “Woman’s Conquest in Filmdom,” Motion Picture Supplement, September 1915, 41.

- Kathryn H. Fuller, At the Picture Show: Small-Town Audiences and the Creation of Movie Fan Culture (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996), 140.

- “‘Recruiting Stations of Vice’: A Libel on Moving Picture Theaters,” Moving Picture World, March 12, 1910, 370-371.

- Susan A. Glenn, Female Spectacle: The Theatrical Roots of Modern Feminism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 147.

- Martin F. Norden, “A Good Travesty Upon the Suffragette Movement: Women’s Suffrage Films as Genre,” Journal of Popular Film and Television 13, no. 4 (1986), 175.

- Sloan, Loud Silents, 99.

- Ibid.

- Tom Gunning, “Early Cinema as Global Cinema: The Encyclopedic Ambition,” in Early Cinema and the “National,” edited by Richard Abel, Giorgio Bertellini, and Rob King (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016), 11.

- Sloan, Loud Silents, 103-104.

- Some examples of these films are “For the Cause of Suffrage” (Méliès 1909), “She Would Be a Business Man” (Centaur, 1910), and “The Suffragette’s Dream” (Pathé Frères, 1909). All three of these films are, to my knowledge, presumed lost. Plot details are from The Moving Picture World, November 6, 1909, 644; July 7, 1910, 144; and March 6, 1909, 282, respectively.

- Hennefeld, Specters of Slapstick, 184-189.

- “Moving Pictures to Aid Woman’s Cause,” Motography, August 1911, 81.

- “Bring Out Picture Play,” Woman’s Journal, October 10, 1914, 276.

- Sloan, Loud Silents, 108.

- “Suffrage and the Man,” Moving Picture World, June 8, 1912, 962.

- Gretchen Bataille, “Preliminary Investigations: Early Suffrage Films,” Women and Film 1, nos. 3 & 4 (1973): 44.

- W. Stephen Bush, review of Eighty Million Women Want—?, Unique Film Company, Moving Picture World, November 15, 1913, 741. There is an alternate title, 80 Million Women Want–?, that is used in the film’s intertitles and in some reviews, but it is more likely, given the prevalence of the first title and its use in the seemingly original beginning-of-reel cards in the extant print, that it was simply an abbreviation.

- Vachel Lindsay, The Art of the Moving Picture (New York: MacMillan, 1915; New York: Liveright, 1970), 259.

- Sloan, Loud Silents, 100-104.

- “What Eighty Million Women Want–,” Moving Picture World, November 8, 1913, 660.

- For an example of this argument, see Bataille, “Preliminary Investigations,” 42-44.

- “For the Cause of Suffrage,” Moving Picture World, November 6, 1909, 644.

- Anne Page, “Suffrage Cause Aided by ‘Movies,’” The Graphic, June 22, 1912, 6.

- Kraditor, Ideas of Woman Suffrage, 44-46.

- Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1966): 152-153.

- McCammon, “Suffrage Sentiment,” 461.

- Shore, Suffrage and the Silver Screen, 11. Italics in the original.

- William M. Henry, “Cleo, the Craftswoman,” Photoplay Magazine, January 9, 1916, 109.

- According to the listings of “current films” published in Motography, Her Defiance was released on January 14, 1916, while Eleanor’s Catch was released on May 9, 1916.

- Kraditor, Ideas of Woman Suffrage, 105-106.

- James S. McQuade, review of Your Girl and Mine, Selig Polyscope, Moving Picture World, November 7, 1914, 764.

- Notes to Hypocrites & Eleanor’s Catch (New York: Kino Lorber, 2008), DVD.

- Mark Garrett Cooper, Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 179. Italics in the original.

- “Pearl White Moralizes in Replying to Attack on Influence of Movies,” New York Tribune, December 7, 1919.

- Kraditor, Ideas of Woman Suffrage, 118.

- Shelley Stamp, Movie-Struck Girls: Women and Motion Picture Culture After the Nickelodeon (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 41-45.

- Cooper, Universal Women, 174.

- Stamp, Movie-Struck Girls, 88-89.

- Brooke Kroeger, The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote (New York: Excelsior Editions, 2017), 3-5.

- Clifford G. Roe, What Women Might Do with the Ballot: The Abolition of the White Slave Traffic (New York: National Woman Suffrage Association, 1912).