Abstract

Background: The prescription drugs or drug classes that are most frequently associated with death in the US might be identifiable from death certificate data.

Objective: To identify the drugs/drug classes associated with the greatest numbers of deaths in the US that might be considered as possible targets for prevention.

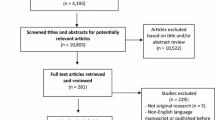

Study design: US vital statistics data were accessed in order to identify International Classification of Diseases (10th Revision) [ICD-10] codes indicating that prescription drugs had caused or contributed to death and diseases with significant drug-related mortality.

Main outcome measure: ICD-10 codes for primarily prescription drugs that were listed as the underlying cause or as ‘total mentions’ on death certificates and were implicated in ≥1000 deaths in any one year were selected. The annual number of deaths by ICD-10 code was obtained from the Division of Vital Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics. Codes for diseases with significant drug-related aetiologies and involvement in ≥1000 deaths in any one year were also identified and analysed separately.

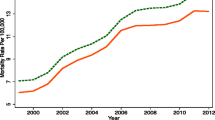

Results: For the selected ICD-10 codes, a total of 25 031 deaths were listed as having a prescription drug as the underlying cause in 2003, compared with 16 135 in 1999, a 55% increase. Total mentions of these codes increased from 46 523 in 1999 to 72 080 in 2003, also a 55% increase. Most codes involved ‘poisonings’ (overdose or the wrong substance given or taken in error that is accidental, intentional or with undetermined intent). Drugs associated with poisoning deaths had central nervous system effects. Among the codes associated with specified drug classes, poisonings and accidental poisonings involving narcotics, hallucinogens, psychoactive substances and opioids (other than opium and heroin) were associated with the largest numbers of deaths. Drug-related codes associated with the largest percentage increases in deaths between 1999 and 2003 included poisoning due to methadone (275%); poisoning by other and unspecified antidepressants (primarily selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) [130%]; and poisoning by psychostimulants with potential for abuse (amfetamines and drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) [117%]. Anticoagulants were associated with the largest numbers of deaths with codes involving “adverse effects in therapeutic use”. Among diseases with significant drug-related aetiologies, Clostridium difficile enterocolitis (associated primarily with antibacterials) had the largest percentage increase in total mentions, with a 203% rise between 1999 and 2003.

Conclusions: Deaths due to overdoses are the most prominent cause of drug-related mortality in death certificate data. Certain drugs and drug classes, especially the opioids (e.g. narcotics, methadone), psychoactive drugs (e.g. antidepressants, amfetamines), anticoagulants and antibacterials (which cause or contribute to C. difficile enterocolitis) are associated with large and increasing numbers of deaths and preventive strategies should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wysowski DK, Swartz L. Adverse drug event surveillance and drug withdrawals in the United States, 1969–2002: the importance of reporting suspected reactions. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 1363–9

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth revision, (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992: volume 1

Public use data tape documentation. Multiple cause of death for ICD-10 1999–2003 data. Hyattsville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics, 1999–2003 [online]. Available from URL: http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/sc_data/mort/mcmort/type_txt/mcmort03/ControlTotalTable1.pdf [Accessed 2007 Apr 27]

Pepin J, Valiquette L, Alary M-E, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1999 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ 2004; 171: 466–72

Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2442–9

Bartlett JG, Perl TM. The new Clostridium difficile — what does it mean? N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2503–5

Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Levy M, et al. The drug etiology of agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia: monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics, volume 18. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991

Ibanez L, Vidal X, Laporte JR. Population-based drug-induced agranulocytosis. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 869–74

Shapiro S, Issaragrisil S, Kaufman DW, et al. Agranulocytosis in Bangkok, Thailand: a predominantly drug-induced disease with an unusually low incidence. Aplastic Anemia Study Group. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 60: 573–7

Griffin MR, Ray WA, Schaffner W. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and death from peptic ulcer in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109: 359–63

Lassen A, Hallas J, de Muckadell OB. Complicated and uncomplicated peptic ulcers in a Danish county 1993–2002: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 945–53

Pierce LR, Wysowski DK, Gross TP. Myopathy and rhabdomyolysis associated with lovastatin-gemfibrozil combination therapy. JAMA 1990; 264: 71–5

Graham DJ, Staffa JA, Shatin D, et al. Incidence of hospitalized rhabdomyolysis in patients treated with lipid-lowering drugs. JAMA 2004; 292: 2585–90

Cannon ML, Glazier SS, Bauman LA. Metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, and cardiovascular collapse after prolonged propofol infusion. J Neurosurg 2001; 95: 1053–6

Wysowski DK, Pollock ML. Reports of death with use of propofol (Diprivan) for nonprocedural (long-term) sedation and literature review. Anesthesiology 2006; 105: 1047–51

Wysowski DK, Nourjah P. Analyzing prescription drugs as causes of death on death certificates. Public Health Rep 2004; 119: 520

Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997; 10: 720–41

Melli G, Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR. Rhabdomyolysis: an evaluation of 475 hospitalized patients. Medicine 2005; 84: 377–85

Sinert R, Kohl L, Rainone T, et al. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Ann Emerg Med 1994; 23: 1301–6

Wysowski DK, Governale LA, Swann J. Trends in outpatient prescription drug use and related costs in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2006; 24: 233–6

Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006; 15: 618–27

Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA. Diversion and abuse of methadone prescribed for pain management. JAMA 2005; 293: 297–8

Dart RC, Woody GE, Kleber HD. Prescribing methadone as an analgesic. Ann Intern Med 2005; 143: 620

Mueller MR, Shah NG, Landen MG. Unintentional prescription drug overdose deaths in New Mexico, 1994–2003. Am J Prev Med 2006; 30: 423–9

Cone EJ, Fant RV, Rohay JM, et al. Oxycodone involvement in drug abuse deaths: a DAWN-based classification scheme applied to an oxycodone postmortem database containing over 1000 cases. J Anal Toxicol 2003; 27: 57–67

Fingerhut LA. Increase in methadone-related deaths: 1999–2004 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/methadonel999-04/methadonel999-04.htm [Accessed 2007 May 7]

Tharp AM, Winecker RE, Winston DC. Fatal intravenous fentanyl abuse: four cases involving extraction of fentanyl from transdermal patches. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2004; 25: 178–81

Barrueto F Jr, Howland MA, Hoffman RS. The fentanyl tea bag. Vet Hum Toxicol 2004; 46: 30–1

Meadows M. Proper use of fentanyl pain patches. FDA Consumer magazine March–April, 2006

Wysowski DK. Increase in deaths related to enterocolitis due to Clostridium difficle in the United States, 1999–2002. Public Health Rep 2006; 121: 361–2

Acknowledgements

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US FDA. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this manuscript. The author has no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wysowski, D.K. Surveillance of Prescription Drug-Related Mortality Using Death Certificate Data. Drug-Safety 30, 533–540 (2007). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200730060-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200730060-00007