Abstract

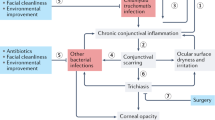

Trachoma is a significant public health problem that is endemic in 57 countries, affecting 40.6 million people and contributing to 4% of the global burden of blindness. Repeated episodes of infection from Chlamydia trachomatis lead to long-term inflammation, scarring of the tarsal conjunctiva and distortion of the upper eyelid with in-turning of eyelashes that abrade the surface of the globe. This constant abrasion, in turn, can cause irreversible corneal opacity and blindness. The Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020 (GET2020) has adopted the SAFE (Surgery, Antibiotics, Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvement) strategy as the main action against trachoma. Trichiasis surgery reduces the risk of blindness by reversing the in-turning of eyelashes and also improves the quality of life from non-visual symptoms. However, future efforts need to aim at increasing accessibility to surgery and improving acceptance. Antibacterials are required to reduce the burden of infection. Oral azithromycin is as close to the perfect antibacterial as we will get for mass distribution: it is safe, requires only a single oral dose, treatment is usually repeated every 6–12 months, resistance is not seen as a problem, and cost is not a limiting factor with a large donation programme and newer generic versions of the drug. Future focus should be on the details of antibacterial distribution such as coverage, frequency of distribution and target population. The promotion of facial cleanliness through education may be the key to trachoma elimination as it will stop the frequent exchange of infected ocular secretions and thus reduce the transmission of infection. However, innovative methods are required to translate health education and promotion activities into sustainable changes in hygiene behaviour. Environmental improvements should focus on the barriers to achieving facial cleanliness and cost-effective means need to be identified. There are a number of countries already eligible for certification of trachoma elimination and if current momentum continues, blinding trachoma can be eliminated by the year 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Taylor HR. Trachoma: a blinding scourge from the bronze age to the twenty-first century. Melbourne (VIC): Centre for Eye Research Australia, 2008

Mariotti SP, Pascolini D, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Trachoma: global magnitude of a preventable cause of blindness. Br J Ophthalmol. Epub 2008 Dec 19

World Health Organization, International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, VISION 2020. Global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness, action plan 2006–2011. Geneva, World Health Organization, International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, VISION 2020, 2007

Abdou A, Nassirou B, Kadri B, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for trachoma and ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Niger. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91: 13–7

Courtright P, Sheppard J, Lane S, et al. Latrine ownership as a protective factor in inflammatory trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol 1991; 75: 322–5

Katz J, West KP, Khatry SK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for trachoma in Sarlahi district, Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 1996; 80: 1037–41

West SK, Munoz B, Mkocha H, et al. Progression of active trachoma to scarring in a cohort of Tanzanian children. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001; 8: 137–44

Guzey M, Ozardali I, Basar E, et al. A survey of trachoma: the histopathology and the mechanism of progressive cicatrization of eyelid tissues. Ophthalmologica 2000; 214(4): 277–84

Bowman RJ, Jatta B, Cham B, et al. Natural history of trachomatous scarring in the Gambia: results of a 12-year longitudinal follow-up. Ophthalmology 2001; 108(12): 2219–24

Marx R. Social factors and trachoma: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 1989; 29(1): 23–34

Polack S, Brooker S, Kuper H, et al. Mapping the global distribution of trachoma. Bull World Health Org 2005; 83: 913–9

Luna EJA, Medina NH, Oliveira MB, et al. Epidemiology of trachoma in Bebedouro State of Sao Paulo, Brazil: prevalence and risk factors. Int J Epidemiol 1992; 21(1): 169–77

Hsieh Y, Bobo LD, Quinn TC, et al. Risk factors for trachoma: 6-year follow-up. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 152(3): 204–11

Taylor HR, West S, Mmbaga BBO, et al. Hygiene factors and increased risk of trachoma in central Tanzania. Arch Ophthalmol 1989; 107: 1821–5

Wright HR, Turner A, Taylor HR. Trachoma. Lancet 2008; 371: 1945–54

Patton DL, Wang SK, Kuo CC. The activity of azithromycin on the infectivity of Chlamydia trachomatis in human amniotic cells. J Antimicrob Chemother 1995; 36(6): 951–9

Beatty WL, Morrison RP, Byrne GI. Persistent chlamydiae-from cell-culture to a paradigm for chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev 1994; 58(4): 686–99

World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, International Trachoma Initiative. Trachoma control: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, International Trachoma Initiative, 2006

Mariotti SP, Pararajasegaram R, Resnikoff S. Trachoma: looking forward to global elimination of trachoma by 2020 (GET 2020). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003; 69: 33–5

Lietman TM, Fry A. Can we eliminate trachoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 385–7

Emerson PM, Cairncross S, Bailey RL, et al. Review of the evidence base for the ‘F’ and ‘E’ components of the SAFE strategy for trachoma control. Trop Med Int Health 2000; 5(8): 515–27

Reacher MH, Munoz B, Alghassany A, et al. A controlled trial of surgery for trachomatous trichiasis of the upper lid. Arch Ophthalmol 1992; 110(5): 667–74

Reacher M, Foster A, Huber J. Trichiasis surgery for trachoma: the bilamellar tarsal rotation procedure. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1993. Report no. WHO/PBL/93.29

Thanh TTK, Khandekar R, Luong VQ, et al. One year recurrence of trachomatous trichiasis in routinely operated Cuenod Nataf procedure cases in Vietnam. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88(9): 1114–8

West SK, Bedri A, Thanh TTK, et al. Final assessment of trichiasis surgeons. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Report no. WHO/PBD/GET/05.2

Bog H, Yorston D, Foster A. Results of community-based eyelid surgery for trichiasis due to trachoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1993; 77(2): 81–3

Zhang H, Kandel RP, Sharma B, et al. Risk factors for recurrence of postoperative trichiasis: implications for trachoma blindness prevention. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122(4): 511–6

West ES, Mkocha H, Munoz B, et al. Risk factors for postsurgical trichiasis recurrence in a trachoma-endemic area. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46(2): 447–53

Merbs SL, West SK, West ES. Pattern of recurrence of trachomatous trichiasis after surgery surgical technique as an explanation. Ophthalmology 2005; 112(4): 705–9

Burton MJ, Bowman RJC, Faal H, et al. Long term outcome of trichiasis surgery in the Gambia. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89(5): 575–9

Burton MJ, Kinteh F, Jallow O, et al. A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin following surgery for trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89(10): 1282–8

Zhang H, Kandel RP, Atakari HK, et al. Impact of oral azithromycin on recurrence of trachomatous trichiasis in Nepal over 1 year. Br J Ophthalmol 2006 Aug; 90(8): 943–8

West SK, West ES, Alemayehu W, et al. Single-dose azithromycin prevents trichiasis recurrence following surgery: randomized trial in Ethiopia. Arch Ophthalmol 2006; 124(3): 309–14

Rabiu MM, Abiose A. Magnitude of trachoma and barriers to uptake of lid surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001; 8(2–3): 181–90

Bowman RJC, Faal H, Jatta B, et al. Longitudinal study of trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia: barriers to acceptance of surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002; 43(4): 936–40

Burton MJ, Bowman RJC, Faal H, et al. The long-term natural history of trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47(3): 847–52

Nagpal G, Dhaliwal U, Bhatia MS. Barriers to acceptance of intervention among patients with trachomatous trichiasis or entropion presenting to a teaching hospital. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13(1): 53–8

Bowman RJ, Soma OS, Alexander N, et al. Should trichiasis surgery be offered in the village? A community randomised trial of village vs health centre-based surgery. Trop Med Int Health 2000; 5(8): 528–33

Mahande M, Tharaney M, Kirumbi E, et al. Uptake of trichiasis surgical services in Tanzania through two village-based approaches. Br J Ophthalmol 2007 Feb; 91(2): 139–42

Lewallen S, Mahande M, Tharaney M, et al. Surgery for trachomatous trichiasis: findings from a survey of trichiasis surgeons in Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol 2007 Feb; 91(2): 143–5

Dhaliwal U, Bhatia M. Health-related quality of life in patients with trachomatous trichiasis or entropion. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13: 59–66

Baltussen RM, Sylla M, Frick KD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of trachoma control in seven world regions. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2005; 12(2): 91–101

Baltussen R, Sylla M, Mariotti SP. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cataract surgery: a global and regional analysis. Bull World Health Org 2004; 82(5): 338–45

Dawson CR, Daghfous T, Whitcher J, et al. Intermittent trachoma chemotherapy: a controlled trial of topical tetracycline or erythromycine. Bull World Health Org 1981; 59(1): 91–7

Sanchez AR, Rogers RS, Sheridan PJ. Tetracycline and other tetracycline-derivative staining of the teeth and oral cavity. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43(10): 709–15

Maitchouk IF. Report of blindness in the Middle East. Cairo: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, World Health Organization, 1976 Mar. Report no.: EM/ICP/VIR/001/RB

Schachter J, West SK, Mabey D, et al. Azithromycin in control of trachoma. Lancet 1999 Aug; 354(9179): 630–5

Bailey RL, Arullendran P, Whittle HC, et al. Randomised controlled trial of single-dose azithromycin in treatment of trachoma. Lancet 1993 Aug; 342(8869): 453–6

Taylor HR. Report of a workshop: research priorities for the control of trachoma. J Infect Dis 1985; 152(2): 383–8

Hoepelman IM, Schneider MM. Azithromycin: the first of the tissue-selective azalides. Int J Antimicrob Agents 1995; 5(3): 145–67

Pfizer Inc. Zithromax (azithromycin tablets) and (azithromycin for oral suspension) 70-5179-00-4. Product Insert 2004; 70: 1–32

Wood N, McIntyre P. Pertussis: review of epidemiology, diagnosis, management and prevention. Paediatr Respir Rev 2008 Sep; 9(3): 201–11; quiz 11-2

Gray RH, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kigozi G, et al. Randomized trial of presumptive sexually transmitted disease therapy during pregnancy in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 185(5): 1209–17

2006 UK National Guideline for the Management of Genital Tract Infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. [online]. Available from URL: http://www.bashh.org/documents/61/61.pdf [Accessed 2009 Apr 3]

Tabbara KF, AEl-Asrar AMA, Al-Omar O, et al. Single-dose azithromycin in the treatment of trachoma. Ophthalmology 1996; 103: 842–6

Karcioglu ZA, El-Yazigi A, Jabak MH, et al. Pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in trachoma patients. Ophthalmology 1998; 105: 658–61

Mabey D, Fraser-Hurt N. Antibiotics for trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (2): CD001860

Wright HR, Keeffe JE, Taylor HR. Elimination of trachoma: are we in danger of being blinded by the randomized controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 1339–40

Dawson CR, Schachter J, Sallam S, et al. A comparison of oral azithromycin with topical oxytetracycline/polymyxine for the treatment of trachoma in children. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 24: 363–8

Bowman RJ, Sillah A, Van Dehn C, et al. Operational comparison of single-dose azithromycin and topical tetracycline for trachoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000; 41(13): 4074–9

Fraser-Hurt N, Bailey RL, Cousens S, et al. Efficacy of oral azithromycin versus topical tetracycline in mass treatment of endemic trachoma. Bull World Health Org 2001; 79: 632–40

Chidambaram JD, Alemayehu W, Melese M, et al. Effect of a single mass antibiotic distribution on the prevalence of infectious trachoma. JAMA 2006 Mar; 295(10): 1142–6

Solomon AW, Holland MJ, Alexander NDE, et al. Mass treatment with single-dose azithromycin for trachoma. N Engl J Med 2004 Nov; 351(19): 1962–71

Solomon AW, Harding-Esch E, Alexander NDE, et al. Two doses of azithromycin to eliminate trachoma in a Tanzanian community. N Engl J Med 2008 Apr; 358(17): 1870–1

Melese M, Chidambaram JD, Alemayehu W, et al. Feasibility of eliminating ocular Chlamydia trachomatis with repeat mass antibiotic treatments. JAMA 2004 Aug; 292(6): 721–5

West S, Munoz BE, Mkocha H, et al. Infection with Chlamydiatrachomatisafter mass treatment of a trachoma hyperendemic community in Tanzania: a longitudinal study. Lancet 2005; 366: 1296–300

International Trachoma Initiative 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.trachoma.org [Accessed 2009 Apr 3]

Emerson P, Burton M, Solomon AW, et al. The SAFE strategy for trachoma control: using operational research for policy, planning and implementation. Bull World Health Org 2006; 84(8): 613–9

World Health Organization, editor. Report of the Twelfth Meeting of the World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma; 2008 Apr 28–30; Geneva

Cochereau I, Goldschmidt P, Goepogui A, et al. Efficacy and safety of short duration azithromycin eye drops versus azithromycin single oral dose for the treatment of trachoma in children: a randomised, controlled, double-masked clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2007 May; 91(5): 667–72

Kuper H, Wormald R. Topical azithromycin: new evidence? Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91(5): 566–7

Frick KD, Lietman TM, Holm SO, et al. Cost-effectiveness of trachoma control measures: comparing targeted household treatment and mass treatment of children. Bull World Health Org 2001; 79(3): 201–7

West SK, Munoz B, Mkocha H, et al. Trachoma and ocular Chlamydiatrachomatiswere not eliminated three years after two rounds of mass treatment in a trachoma hyperendemic village. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48(4): 1492–7

West ES, Munoz B, Mkocha H, et al. Mass treatment and the effect on the load of Chlamydiatrachomatisinfection in a trachoma-hyperendemic community. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46(1): 83–7

Burton M, Holland MJ, Faal N, et al. Which members of a community need antibiotics to control trachoma? Conjunctival Chlamydiatrachomatisinfection load in gambian villages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003; 44(10): 4215–22

Bird M, Dawson CR, Schachter JS, et al. Does the diagnosis of trachoma adequately identify ocular chlamydial infection in trachoma-endemic areas? J Infect Dis 2003 May; 187(10): 1669–73

Tielsch JM, West KP, Katz J, et al. The epidemiology of trachoma in southern Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1988; 38(2): 393–9

Taylor HR, Velasco FM, Sommer A. The ecology of trachoma: an epidemiological study in southern Mexico. Bull World Health Org 1985; 63(3): 559–67

West S, Rapoza PE, Munoz BE, et al. Epidemiology of ocular chlamydial infection in a trachoma-hyperendemic area. J Infect Dis 1991; 163: 752–6

Broman AT, Shum K, Munoz B, et al. Spatial clustering of ocular chlamydial infection over time following treatment, among households in a village in Tanzania. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47(1): 99–104

Holm SO, Jha HC, Bhatta RC, et al. Comparison of two azithromycin distribution strategies for controlling trachoma in Nepal. Bull World Health Org 2001; 79(3): 194–200

Schemann JF, Guinot C, Traore L, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of three azithromycin distribution strategies for treatment of trachoma in a sub-Saharan African country, Mali. Acta Trop 2007 Jan; 101(1): 40–53

Shelby-James TM, Leach AJ, Carapetis JR, et al. Impact of single dose azithromycin on group A streptococci in the upper respiratory tract and skin of Aboriginal children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002; 21(5): 375–80

Fry AM, Jha HC, Lietman TM, et al. Adverse and beneficial secondary effects of mass treatment with azithromycin to eliminate blindness due to trachoma in Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 2002 Aug; 35(4): 395–402

Chidambaram JD, Melese M, Alemayehu W, et al. Mass antibiotic treatment and community protection in trachoma control programs. Clin Infect Dis 2004 Nov; 39(9): e95–7

House JI, Ayele B, Porco TC, et al. Assessment of herd protection against trachoma due to repeated mass antibiotic distributions: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2009; 373: 1111–8

Solomon AW, Holland MJ, Burton MJ, et al. Strategies for control of trachoma: observational study with quantitative PCR. Lancet 2003; 362: 198–204

Taylor HR, Siler JA, Mkocha HA, et al. The natural history of endemic trachoma: a longitudinal study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1992; 46(5): 552–9

Abbott Laboratories. Erythromycin. [online]. Available from URL: http://www.rxabbott.com/pdf/erythromycin.pdf [Accessed 2009 Apr 3]

Tiwari T, Murphy TV, Moran J; National Immunization Program, CDC. Recommended antimicrobial agents for the treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC Guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54: 1–16

Centre for Disease Control. CDC guidelines for management of trachoma in the northern territory (draft). Darwin (NT): Centre for Disease Control, 2008

Congdon N, West S, Vitale S, et al. Exposure to children and risk of active trachoma in Tanzanian women. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 137(3): 366–72

Taylor HR. Misleading titles cause confusion [letter]. Arch Ophthalmol 2009; 127(2): 225

Burton MJ, Holland MJ, Makalo P, et al. Re-emergence of Chlamydiatrachomatisinfection after mass antibiotic treatment of a trachoma-endemic Gambian community: a longitudinal study. Lancet 2005 Apr; 365(9467): 1321–8

Lietman T, Porco T, Dawson C, et al. Global elimination of trachoma: how frequently should we administer mass chemotherapy? Nat Med 1999; 5(5): 572–6

Melese M, Alemayehu W, Lakew T, et al. Comparison of annual and biannual mass antibiotic administration for elimination of infectious trachoma. JAMA 2008 Feb; 299(7): 778–84

Su H, Morrison R, Messer R, et al. The effect of doxycycline treatment and the development of protective immunity in a murine model of chlamydial genital infection. J Infect Dis 1999; 180(4): 1252–8

Brunham RC, Pourbohloul B, Mak S, et al. The unexpected impact of a Chlamydiatrachomatisinfection control program on susceptibility to reinfection. J Infect Dis 2005; 192(10): 1836–44

Dicker LW, Mosure DJ, Levine WC, et al. Impact of switching laboratory tests on reported trends in Chlamydia trachomatisinfections. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 151(4): 430–5

Ray KJ, Porco TC, Hong KC, et al. A rationale for continuing mass antibiotic distributions for trachoma. BMC Infect Dis 2007 Aug; 7: 91

Wright HR, Taylor HR. Clinical examination and laboratory tests for estimation of trachoma prevalence in a remote setting: what are they really telling us? Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5: 313–20

Davies PO, Ridgway GL. The role of polymerase chain reaction and ligase chain rection for the detection of Chlamydiatrachomatis. Int J STD AIDS 1997; 8: 731–8

Bailey RL, Hampton TJ, Hayes LJ, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of ocular Chlamydial infection in trachoma-endemic communities. J Infect Dis 1994; 170: 709–12

Taylor HR, Johnson SL, Prendergast RA, et al. An animal model of trachoma: II. The importance of repeated reinfection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1982; 23(4): 507–15

Michel C-EC, Solomon AW, Magbanua JPV, et al. Field evaluation of a rapid point-of-care assay for targeting antibiotic treatment for trachoma control: a comparative study. Lancet 2006 May; 367(9522): 1585–90

Solomon AW, Foster A, Mabey DCW. Clinical examination versus Chlamydiatrachomatisassays to guide antibiotic use in trachoma control programmes. Lancet Infect Dis 2006; 6(1): 5–6

Atik B, Thanh TTK, Luong VQ, et al. Impact of annual targeted treatment on infectious trachoma and susceptibility to reinfection. JAMA 2006 Sep; 296(12): 1488–97

Mabey D, Solomon AW. Mass antibiotic administration for eradication of ocular Chlamydiatrachomatis. JAMA 2008 Feb; 299(7): 819–21

Ridgway GL, editor. Antibiotic resistance in human chlamydial infection: should we be concerned? Tenth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections; 2002 Jun 16–21; Antalya

Schiedler V, Bhatta RC, Miao Y, et al. Pattern of antibiotic use in a trachoma-endemic region of Nepal: implications for mass azithromycin distribution. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2003; 10(1): 31–6

Leach AJ, Shelby-James TM, Mayo M, et al. A prospective study of the impact of community-based azithromycin treatment of trachoma on carriage and resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 24(3): 356–62

Chern KC, Shreshta B, Cevallos V, et al. Alterations in the conjunctival bacterial flora following a single dose of azithromycin in a trachoma endemic area. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 1332–5

Gaynor BD, Chidambaram JD, Cevallos V, et al. Topical ocular antibiotics induce bacterial resistance at extraocular sites. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89(9): 1097–9

Hyde TB, Gay K, Stephens DS, et al. Macrolide resistance among invasive Streptococcuspneumoniaeisolates. JAMA 2001 Oct; 286(15): 1857–62

Schemann JF, Guinot C, Ilboudo L, et al. Trachoma, flies and environmental factors in Burkina Faso. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2003; 97: 63–8

Schemann JF, Sacko D, Malvy D, et al. Risk factors for trachoma in Mali. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 194–201

Cumberland P, Hailu G, Todd J. Active trachoma in children aged three to nine years in rural communities in Ethiopia: prevalence, indicators and risk factors. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2005; 99(2): 120–7

Mesfin MM, de la Camera J, Tareke IG, et al. A community-based trachoma survey: prevalence and risk factors in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13: 173–81

West S, Munoz B, Lynch M, et al. Impact of face-washing on trachoma in Kongwa, Tanzania. Lancet 1995 Jan; 345(8943): 155–8

Cumberland P, Edwards T, Hailu G, et al. The impact of community level treatment and preventative interventions on trachoma prevalence in rural Ethiopia. Int J Epidemiol 2008 Jun; 37(3): 549–58

Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Matthews F, et al. Effect of 3 years of SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental change) strategy for trachoma control in southern Sudan: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2006; 368: 589–95

Ngondi J, Matthews F, Reacher M, et al. Associations between active trachoma and community intervention with antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvement (A,F,E). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008 Apr; 2(4): E229

Khandekar R, Ton TKT, Do Thi P. Impact of face washing and environmental improvement on reduction of active trachoma in Vietnam: a public health intervention study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13(1): 43–52

Mariotti SP, Pruss A. Preventing trachoma: a guide for environmental sanitation and improved hygiene. Geneva: World Health Organization, International Trachoma Initiative, 2001

Taylor HR. Doyne lecture: trachoma, is it history? Eye. Epub 2009 Mar 6

Emerson PM, Lindsay SW, Alexander N, et al. Role of flies and provision of latrines in trachoma control: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 363(9415): 1093–8

Emerson P, Lindsay SW, Walraven GEL, et al. Effect of fly control on trachoma and diarrhoea. Lancet 1999; 353: 1401–3

West S, Emerson P, Mkocha H, et al. Intensive insecticide spraying for fly control after mass antibiotic treatment for trachoma in a hyperendemic setting: a randomized trial. Lancet 2006; 368: 596–600

Barreto ML, Genser B, Strina A, et al. Effect of city-wide sanitation programme on reduction in rate of childhood diarrhoea. Lancet 2007; 370(9599): 1622–8

World Health Organization, editor. Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care; 1978 Sep 6–12 Alma-Ata, USSR. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1978

United Nations. UN millennium goals [online]. Available from URL: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals [Accessed 2009 Apr 3]

Chan M. Return to Alma-Ata. Lancet 2008 Sep; 372(9642): 865–6

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mathew, A.A., Turner, A. & Taylor, H.R. Strategies to Control Trachoma. Drugs 69, 953–970 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200969080-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200969080-00002