Abstract

For nearly 50 years, antidepressant drugs have been the first-line treatment for various forms of depression. Despite their widespread use, these medications have significant shortcomings, in particular problems of patient compliance due to adverse effects. The introduction of new formulations of existing antidepressant medications may provide patients with benefits in terms of convenience of use. As a consequence, improvements in compliance may lead to better antidepressant efficiency.

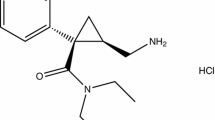

An orally disintegrating formulation of mirtazapine (mirtazapine SolTab®), a once-weekly formulation of fluoxetine, an enantiomer-specific formulation of citalopram (escitalopram), an extended-release formulation of venlafaxine (venlafaxine XR), a controlled-release formulation of paroxetine (paroxetine CR) and intravenous formulations of some of the newer antidepressants have all been evaluated in limited clinical trials. In this article, a review of the pharmacokinetics and clinical evaluations of these formulations is presented.

While there do not appear to be major clinical advantages for the new formulations in terms of antidepressant efficacy, none of them is less efficacious than their older counterpart. Indeed, some of the new formulations are more acceptable to patients (fluoxetine once-weekly, paroxetine CR), others have pharmacokinetic advantages (venlafaxine XR, paroxetine CR), while others may have a faster onset of effect (mirtazapine SolTab®, intravenous formulations). Further evaluation of some formulations is still required (mirtazapine SolTab®, fluoxetine once-weekly), while others (venlafaxine XR, escitalopram) are finding widespread acceptance in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Norman TR, Leonard BE. Fast acting antidepressants: can the need be met? CNS Drugs 1994; 2: 120–31

Nierenberg AA. Do some antidepressants work faster than others? J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62Suppl. 15: 22–5

Shelton RS. Cellular mechanisms in the vulnerability to depression and response to antidepressant drugs. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 23: 713–29

Vaidya V, Duman RS. Depression: emerging insights from neurobiology. Br Med Bull 2001; 57: 61–79

Parker G. Classifying depression: should paradigms lost be regained? Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1195–203

Olver JS, Burrows GD, Norman TR. Third generation antidepressants: do they offer advantages over the SSRIs? CNS Drugs 2001; 15: 941–54

Frey R, Schreinzer D, Stimpfl T, et al. Suicide by antidepressant intoxication identified at autopsy in Vienna from 1991–1997: the favourable consequences of the increasing use of SSRIs European Neuropsychopharmacology 2000; 10: 133–42

Baumann P, Zullino DF, Eap CB. Enantiomers’ potential in psychopharmacology: a critical analysis with special emphasis on the antidepressant escitalopram. Eur Neuropharmacol 2002; 12: 433–44

de Boer T, Ruigt GSF, Berendsen HHG. The α2-selective adrenoceptor antagonist Org 3770 enhances noradrenergic and serotonergic transmission. Hum Psychopharmacol 1995; 10Suppl. 2: 107–18

de Boer T, Ruigt GSF. The selective α2-adrenoceptor antagonist mirtazapine (Org 3770) enhances noradrenergic and 5HT1 A: mediated serotonergic neurotransmission. CNS Drugs 1995; 4Suppl. 1: 29–38

Pinder RM. The pharmacologic rationale for the clinical use of antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58: 501–8

Davis R, Wilde MI. Mirtazapine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in the management of major depression. CNS Drugs 1996; 5: 389–402

Burrows GD, Kremer CME. Mirtazapine: clinical advantages in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17Suppl. 1: 34S–9S

Kasper S. Clinical efficacy of mirtazapine: a review of metaanalyses of pooled data. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 10Suppl. 4: 25–35

Timmer CJ, Sitsen JMA, Delbressine LP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine. Clin Pharmacokinet 2000; 38: 461–74

Voortman G, Paanakker JE. Bioavailability of mirtazapine from Remeron tablets after single and multiple oral dosing. Hum Psychopharmacol 1995; 10 Suppl.: S83–96

Delbressine LPC, Moonen MEG, Kaspersen FM, et al. Pharmacokinetics and biotransformation of mirtazapine in human volunteers. Clin Drug Invest 1998; 15: 45–55

van den Heuvel MW, Kleijn HJ, Peeters PAM. Bioequivalence trial of orally disintegrating mirtazapine tablets and conventional oral mirtazapine tablets in healthy volunteers. Clin Drug Invest 2001; 21: 437–42

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

Kennedy S, Vester-Blokland ED, RAPID Study Group. Mirtazapine (Remeron, Sol-Tab) versus sertraline: a prospective onset of action trial. Poster presentation at the 40th Annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; 2001 Dec 10-14; Kona (HI)

Roose SP, Holland PJ, Hassman HA, Rosenthal M, Rodrigues HE. Multi-site, open label, observational study of the effectiveness and safety of Remeron SolTab (mirtazapine orally disintegrating tablets) in depressed patients who are at least 50 years of age. Presented at the 53rd Institute on Psychiatric Services; 2001 Oct 10–14; Orlando (FL)

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157Suppl. 4: 1–45

Tollefson GD, Holman SL, Sayler ME, et al. Fluoxetine, placebo, and tricyclic antidepressants in major depression with and without anxious features. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55: 50–9

Barbui C, Hotopf M, Garattini S. Fluoxetine dose and outcome in antidepressant drug trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacology 2002; 58: 379–86

Roose SP, Glassman AH, Attia E, et al. Cardiovascular effects of fluoxetine in depressed patients with heart disease. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 660–5

Goodnick P. Pharmacokinetic optimisation of therapy with newer antidepressants. Clin Pharmacokinet 1994; 27: 307–30

Judge R. Patient perspectives on once-weekly fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62Suppl. 22: 53–7

Wagstaff AJ, Goa KL. Once weekly fluoxetine. Drugs 2001; 61: 2221–8

Montgomery SA, Baldwin D, Shah A, et al. Plasma-level response relationships with fluoxetine and zimelidine. Clin Neuropharmacol 1990; 13 Suppl. 1: S71–5

Burke WJ, McArthur-Miller DA. Exploring treatment alternatives: weekly dosing of fluoxetine for the continuation phase of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62Suppl. 22: 38–42

Schmidt ME, Fava M, Robinson JM, et al. The efficacy and safety of a new enteric coated formulation of fluoxetine given once weekly during the continuation treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61: 851–7

Schmidt ME, Fava M, Zhang S, et al. Treatment approaches to major depressive disorder relapse. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71: 190–4

Fava M, Schmidt ME, Zhang S, et al. Treatment approaches to major depressive disorder relapse. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71: 195–9

Buongiorno PA, Plewes JM, Wilson MG. Cohort experience in 39 psychiatric outpatients with high doses of an enteric-coated weekly formulation of fluoxetine. Clin Drug Invest 2002; 22: 173–9

Claxton A, de Klerk E, Parry M, et al. Patient compliance to a new enteric-coated weekly formulation of fluoxetine during continuation treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61: 928–32

de Klerk E. Patient compliance with enteric-coated weekly fluoxetine during continuation treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62Suppl. 22: 43–7

Holliday SM, Benfield P. Venlafaxine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in depression. Drugs 1995; 49: 280–94

Wellington K, Perry CM. Venlafaxine extended release: a review of its use in the management of major depression. CNS Drugs 2001; 15: 643–69

Muth EA, Haskins JT, Moyer JA, et al. Antidepressant and biochemical profile of the novel bicyclic compound Wy-45,030, an ethyl cyclohexanol derivative. Biochem Pharmacol 1986; 35: 4493–7

Horst WD, Preskorn SH. The pharmacology and mode of action of venlafaxine. Rev Contemp Pharmacother 1998; 9: 293–302

Klamerus KJ, Maloney K, Rudolph RL, et al. Introduction of a composite parameter to the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine and its active O-desmethyl metabolite. J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 32: 716–24

Parker V, Pruitt L, Maloney K, et al. Effect of age and sex on the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine. J Clin Pharmacol 1990; 30: 832

Muth EA, Moyer JA, Haskins JT, et al. Biochemical, neurophysiological and behavioural effects of Wy-45,233 and other identified metabolites of the antidepressant venlafaxine. Drug Dev Res 1991; 23: 191–9

Merton WA, Sonne SC, Verga MA. Venlafaxine: a structurally unique and novel antidepressant. Ann Pharmacother 1995; 29: 387–95

Troy SM, Dilea C, Martin PT, et al. Bioavailability of once-daily venlafaxine extended release compared with the immediate release formulation in healthy adult volunteers. Curr Ther Res 1997; 58: 492–503

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd edition, revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1987

Cunningham L, for the Venlafaxine XR 208 Study Group. Once-daily venlafaxine extended release (XR) and venlafaxine immediate release (IR) in outpatients with major depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1997; 9: 157–64

Thomas DR, Nelson DR, Johnson AM. Biochemical effects of the antidepressant paroxetine, a specific 5-hydroxytryptamine uptake inhibitor. Psychopharmacology 1987; 93(2): 193–200

Hyttel J. Pharmacological characterisation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 4Suppl. 6: 15–24

Haddock RE, Johnson AM, Langlry PF, et al. Metabolic pathway of paroxetine in animals and man and the comparative pharmacological properties of its metabolites. Acta Psychiat Scand 1989; 80Suppl. 350: 60–75

Bang LM, Keating GM. Paroxetine controlled release. CNS Drugs 2004; 18(6): 355–64

Golden RN, Nemeroff CB, McSorley P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of controlled-release and immediate-release paroxetine in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 577–84

GlaxoSmithKline. Paxil CR™ (paroxetine hydrochloride) controlled-release tablets prescribing information [online]. Available from URL: http://www.gsk.com

Rapoport MH, Schneider LS, Dunner DL, et al. Efficacy of controlled-release paroxetine in the treatment of late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64: 1065–74

Trivedi M, Dillingham K, Pitts CD. Paroxetine CR efficacy and tolerability at low doses in the treatment of major depression. World J Biol Psychiatry 2004; 5 Suppl. 1: 94

Laux G, Konig W, Baumann P. Infusion therapie bei Depressionen Ein Leitfaden fur Klinik und Praxis 4. Aufl., Hippokrates Verlag, Stuttgart 1997

Beaumont G. Oral and intravenous clomipramine (anafranil) in depression. J Int Med Res 1973; 1: 361–4

Faravelli C, Broadhurst AD, Ambonetti A, et al. Double-blind trial with oral versus intravenous clomipramine in primary depression. Biol Psychiatry 1983; 18: 695–706

Guelfi JD, Strub N, Loft H. Efficacy of intravenous citalopram compared with oral citalopram for severe depression: safety and efficacy data from a double-blind, double dummy trial. J Affect Disord 2000; 58: 201–9

Konstantinidis A, Stastny J, Ptak-Butta P, et al. Intravenous mirtazapine in the treatment of depressed inpatients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2002; 12: 57–60

Bouchard JM, Nil R. Benefits of citalopram versus viloxazine, both given as an intravenous-to-oral regimen for severe depression [abstract]. Eur Psychiatry 1998; 13 Suppl. 4: 264S

Baumann P, Nil R, Bertschy G, et al. Intravenous treatment of depressive patients with an SSRI, citalopram: clinical and pharmacokinetic aspects [abstract]. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12Suppl. 2: 106S

Baumann P, Nil R. Citalopram infusion is a useful alternative to tablets in hospitalised patients with depression [abstract]. Eur Psychiatry 1998; 13Suppl. 4: 264S

Tucker GT. Chiral switches. Lancet 2000; 355: 1085–7

Caldwell J. Stereochemical determinants of the nature and consequences of drug metabolism. J Chromatogr A 1995; 694: 39–48

Hutt AJ, Tan SC. Drug chirality and its significance. Drugs 1996; 52Suppl. 5: 1–12

Hyttel J, Bogeso KP, Perregaard J, et al. The pharmacological effect of citalopram resides in the S(+) enantiomer. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 1992; 88: 157–60

Hogg S, Sanchez C. The antidepressant effects of citalopram are mediated by the S (+) not the R(−) enantiomer [abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 9: S213

Montgomery SA, Loft H, Sanchez C, et al. Escitalopram (S-enantiomer of citalopram): clinical efficacy and onset of action predicted from a rat model. Pharmacol Toxicol 2001; 88: 282–6

Wade A, Lemming OM, Hedegaard KB. Escitalopram 10mg/ day is effective and well tolerated in placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 17: 95–102

Burke WJ, Gergel I, Bose A. Fixed dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 331–6

Gorman J, Korotzer A, Su G. Efficacy comparison of escitalopram and citalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: pooled analysis of placebo controlled trials. CNS Spectrums 2002; 7Suppl. 1: 40–4

DeVane CL. Immediate-release versus controlled-release formulations: pharmacokinetics of newer antidepressants in relation to nausea. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64Suppl. 18: 14–9

Kilts CD. Potential new drug delivery systems for antidepressants: an overview. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64Suppl. 18: 31–3

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for the preparation of this article. Associate Professor Trevor Norman has been a funded speaker for Organon, Wyeth, Eli-Lilly and Lundbeck. Both Dr Olver and Associate Professor Norman are currently recipients of a research grant from Eli-Lilly (Australia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Norman, T.R., Olver, J.S. New Formulations of Existing Antidepressants. CNS Drugs 18, 505–520 (2004). https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200418080-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200418080-00003