Residential Production and Spatial Inequalities, a Territorial Analysis from the ‘Right to the City’: The Case of Córdoba Periphery

Mercantilist logic conditions the possibilities of access to urbanised land, space becomes a scarce asset that involves speculative practices, and a deterioration of its quality occurs in a broad sense linked to the deterioration of urban life and the right to the city. (Harvey 2014, de Mattos 2015, 2016, Rolnik 2018, et al.). The work exposes the way in which housing policy has generated conditions for the production of new peripheral territories. For this purpose, some housing complexes of an ambitious public intervention developed during the period 2003–2010 are examined. The methodology is quantitative and comparative, based on the use of Geographic Information Systems (Software QGis). The approach focuses on the spatial dimension of the house as constitutive of the urban environment. The results show its evolution and implications in the urban structure; understanding the importance of recovering the territorial dimension, the urban configuration, and the conditions for the inhabitants in relations with the city. Finally, the physical and social proximity relationships embedded in the production of public housing complexes and the evolution of neighboring residential environments allow us to reflect on the right to the city in the proposed locations of public housing policy.

Show LessType of the Paper: Full Paper

Track title: Metropolization and the Right to the City

Residential Production and Spatial Inequalities, a Territorial Analysis from the ‘Right to the City’: The Case of Córdoba Periphery

M. Cecilia Marengo*

Names of the track editors: Caroline Newton Lei Qu Roberto Rocco

DOI:10.24404/615f9ba0186996000962ba8b Submitted: 08 October 2021 Accepted: 01 June 2022 Published: 23 August 2022 Citation: Marengo, M. (2021). Residential production and spatial inequalities, a territorial analysis from the ‘Right to the City’. The case of Córdoba periphery. The Evolving Scholar | IFoU 14th Edition. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY (CC BY) license. ©2021 [Marengo, M.] published by TU Delft OPEN on behalf of the authors. |

|---|

* National University of Cordoba – Technical & Scientific Research Council (CONICET) Argentina; mcmarengo@unc.edu.ar ; ORCID ID 0000-0001-5670-5390.

Abstract: Mercantilist logic conditions the possibilities of access to urbanised land, space becomes a scarce asset that involves speculative practices, and a deterioration of its quality occurs in a broad sense linked to the deterioration of urban life and the right to the city. (Harvey 2014, de Mattos 2015, 2016, Rolnik 2018, et al.). The work exposes the way in which housing policy has generated conditions for the production of new peripheral territories. For this purpose, some housing complexes of an ambitious public intervention developed during the period 2003–2010 are examined. The methodology is quantitative and comparative, based on the use of Geographic Information Systems (Software QGis). The approach focuses on the spatial dimension of the house as constitutive of the urban environment. The results show its evolution and implications in the urban structure; understanding the importance of recovering the territorial dimension, the urban configuration, and the conditions for the inhabitants in relations with the city. Finally, the physical and social proximity relationships embedded in the production of public housing complexes and the evolution of neighboring residential environments allow us to reflect on the right to the city in the proposed locations of public housing policy.

Keywords: urban growth; social inequalities; housing policies

1. Introduction

Numerous studies indicate that the process of socio-territorial transformations in the new century is associated with the intensification of inequalities (Soja, 2010 Secchi, 2015). Since the 1990s, the periphery of Latin American cities has been associated with a more divided urban space. Social inequalities are manifested in the physical form: dual, polarised, and closed residential areas are built next to impoverished places that concentrate vulnerable population, poverty, and low levels of public investment in services and infrastructure. In the current context of financialization of land and housing (de Mattos 2016, Harvey 2014), there is a growing difficulty in accessing to decent living conditions for a large number of urban residents, which has had a significant impact on the ‘Right to the City’ in terms of access to housing conditions, but also in mobility, services, and accessibility to the structure of opportunities derived from urban development (de Mattos 2016, Rolnik, 2018).

Mercantilist logic conditions the possibilities of access to urbanised land, space becomes a scarce asset that involves speculative practices, and a deterioration of its quality occurs in a broad sense linked to the deterioration of urban life and the right to the city. (Lefevre 1970 cited in De Mattos, 2015). As a result, a highly fragmented peripheral space has been generated, where internally homogeneous but unequal neighbourhoods coexist in a disjointed urbanised territory.

Housing policy does not escape this logic, to the exacerbation of speculative processes of valuation of urban land through the expansion of formal and informal markets that some authors point to as extractivist logic (Svampa &, Viale, 2014). Proof of this is the increasingly distant location of public housing complexes, in peripheral sectors with difficulties in the provision and access to quality services and areas of centrality, (which are configured as possibilities for the use of resources urban, work, education, health, etc.); which represents a tension in relation to the right to the city as access to urban resources and the exercise of participating in the urbanisation process (Harvey, 2014).

In Córdoba Argentina, the spatial growth process is characterised by low densities, discontinuous expansion of urban form, intensification of residential segregation, and urban fragmentation. The research seeks to determine the way in which housing policy has influenced the production of new territories, examining them from the perspective of the Right to the City. For this purpose, some housing complexes of ambitious interventions developed during the period 2003–2010 are examined. Many were located in central or pericentral areas that had suffered floods, or in sectors that were affected by public works. The projects of 12,000 single-family social housing units formed groups of different scales and materialised mainly in peripheral sectors with little urban integration and low-quality in terms of access to the services and equipment in the central city.

The work exposes the way in which housing policy has generated conditions for the production of new peripheral territories that have been configured from its materialisation. More than 10 years after its execution, these territories have transformed their morphology and different situations of changes are recognised at the neighborhood level, derived from the consolidation process itself, as well as the changes in the housing units. Finally, the physical and social proximity relationships embedded in the production of public housing complexes and the evolution of neighboring residential environments allow us to reflect on the right to the city in the proposed locations of the dwellings.

2. Theories and Methods

For Harvey (2014, p.20) “the right to the city is therefore much more than an individual or collective right to the resources that it stores or protects, it is a right to change and reinvent the city with our wishes. It is also a more collective than individual right, since the reinvention of the city depends on the exercise of collective power over urbanisation,” that is to say a collective action. In this sense, the author points out that “the growing polarisation in the distribution of wealth and power are indelibly etched in the spatial forms of our cities in which fortified fragments, gated communities, and public spaces are progressively condensing in privatised areas under constant surveillance” (ibid. p.36). The process is characterised by uneven geographical development and a right to the city in the hands of private interests, because the surpluses of the urbanisation process that are turned over to urban development do so from the hand of private investments. Proof of this is, in the case of Cordoba in recent decades, is the significant growth of gated communities and, on the other hand, of informal settlements in the city periphery (Marengo & Lemma M, 2017; Marengo & Monayar 2020).

In Latin America, the housing policies that have been formulated to meet the demand and the housing deficit in recent years have not provided a comprehensive approach to the issue. They have prioritised the construction of new homes in peripheral and low-quality locations, rather than addressing the structural causes behind unequal access to the urban land market (Fernández Wagner, 2015). The process of commercialisation of housing, the speculative management of the land supply, and the difficulty of locating public housing projects in consolidated areas have led to the emergence of peripheral enclaves where social housing is located. Various studies address issues such as the predominantly quantitative response in addressing the housing deficit, the disconnection of housing production from the guidelines and policies for urban development, the role of international financing agencies in the massive promotion of housing, and the commercialisation of the same expressed in the urbanisation of peripheral and distant land, with high rates of profits for real estate developers (Ziccardi, 2015; Marengo & Elorza, 2018). Public action in Argentina with the Federal Housing Plans that were developed in the first decade of the 21st century (Falú, & Marengo, 2015) has had a significant impact on the reconfiguration and extension of metropolitan spaces by promoting a policy of access to mortgage credit unrelated to access to urbanised land. A condition common to several provinces is the almost null action in terms of urban land policy that can guarantee a provision on a scale to make federal programs viable, leaving public housing policy subject to the operation of land markets forces.

In this framework, a comprehensive approach between housing and land policies, and between the quality of housing and the surroundings, becomes important. In the New Urban Agenda approved at the Habitat III Conference in Quito in 2016, emphasis was placed on how the place of residence for the low-income population represents mechanisms for the reproduction of situations of poverty and territorial inequalities. It points out the role of public policy in terms of urban location, and the scale of intervention and the social conformation of the target population of the housing complexes (Marengo & Elorza, 2018), given that the position of housing in the city allows a reading of certain conditions of opportunity, is linked to the locational capital of the inhabitants. Along these lines, Acioli (2018) raises the need for housing policies to consider “housing in the centre” and promote locations that facilitate access to a better structure of opportunities, as a process that would make the right to the city effective.

To analyse the spatial processes and transformations derived from the location of the massive housing programme, ‘Mi Casa Mi Vida,’ in the city of Córdoba, an approach that integrates quantitative and qualitative analysis was developed. Methodologically data provide by QGIS software, Google Earth satellite images and observations in situ. A secondary source is based on information online from the Cordoba Institute of Spatial Data and census data. The approach focuses on the spatial dimension of the house as constitutive of the urban environment, its evolution and implications in the urban structure; understanding the importance of recovering the territorial dimension, the resulting urban configuration and the conditions for the inhabitants in relations with the city.

3. Results

During the period 2003–2010, the provincial government implemented the public housing policy, the “My House, My Life” programme, the objective was to eradicate slums at environmental risk because they were located in flooded areas. As a result, 70 slums were eradicated in 39 new neighborhoods, all with locations in peripheral areas and in most cases, isolated from the consolidated city. These areas, initially destined for rural/industrial use, required a change in land use pattern to be urbanised (residential). The housing complexes respond to the same organisational typology, blocks with uniform lots of between 250 m2 and 300 m2 and a single serial housing typology of 42 m2. Those on a larger scale (more than 250 houses), have social facilities (primary and secondary schools, health centre, police centre, and commercial areas) and were called ‘neighbourhoods-cities.’ Given that this programme represented one of the largest actions for addressing informal territories, more than 10 years after its materialisation it is interesting to investigate the evolution that they and their environments present.

Case 1. City-neighborhood “Cuartetos”

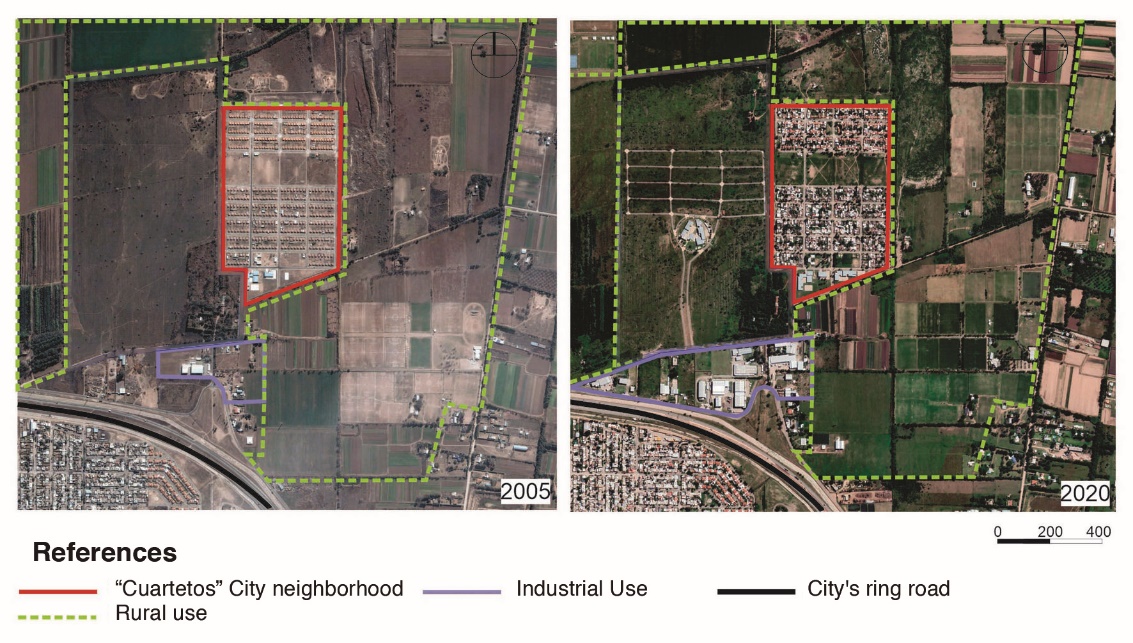

Figure 1. Aerial view of the evolution of “Cuartetos” City neighborhood in 2005 and 2020. Own elaboration.

The neighbourhood was awarded in 2004. It is located to the north outside the city’s ring road in an area initially used for agriculture. It is integrated with 480 houses in two sectors with a green space in the centre, totally isolated from the consolidated urban fabric. The distance to the city centre from the neighbourhood is 10.3 km. It has a single public transport line whose journey to the centre is 65 minutes. When analysing the evolution of the surrounding area in 2020, no changes or building consolidation are observed nearby, only the layout of streets and a building in the adjoining rural plot.

The image of the neighbourhood shows a situation of isolation and little vitality in the streets. However, there is a significant percentage of consolidation in the neighbourhood itself, registering extensions of new area inside the plots in the 85% of cases. (Figure 2)

When analysing the evolution of the land value (in the immediate surroundings of the neighbourhood) in the period 2008–2018, it is observed that the average value per square metre has increased 25 times, which indicates the expectations of future urbanisation due to changes in land uses when the policy was implemented (the plots were initially affected to rural use).

|

|

|

|---|

Figure 2. Street view in the City-neighborhood “Cuartetos” and some houses modified by the inhabitants. By author.

Case 2. City-neighborhood “Angelelli”

Figure 3. Aerial view of the

evolution of “Angelelli” City neighborhood in 2007 and 2020. Own

elaboration.

Figure 3. Aerial view of the

evolution of “Angelelli” City neighborhood in 2007 and 2020. Own

elaboration.

The neighborhood was awarded in 2007. It is located towards the southern sector of the city, in an area of rural use and disconnected from the existing urban fabric. It is integrated with 564 houses in two sectors (N - S). Next to it there is an informal neighbourhood product of the fraudulent subdivision and commercialization of large lots. The distance to the city center is 10.4 km, it has 2 public transport lines and 65 minutes of delay to complete the journey.

When analysing the evolution of the built environment in 2007 to 2020, significant changes are observed in three limits. They are a result of the consolidation of an informal settlement nearby, which maintains the same layout as the housing policy neighbourhood. The consolidation of links with the fraudulent subdivision (present at the time of the inauguration) the largest building consolidation in the informal neighbourhood and incipient processes of private urbanisations (developed by the real estate market) located in the immediate environment, shows a more significant dynamics of change in the surroundings compared to the previous case. Only to the south the use of rural land is maintained.

The dwellings show a significant percentage of consolidation, registering extensions and growths in 88% of cases. When analysing the evolution of the land value (in the immediate surroundings of the neighborhood) in two dates 2008–2018, it is observed that the average value of land (per square meter) has increased 52.86 times in the decade. The dynamics of transformation indicate a greater appreciation of their surroundings due to the change from rural use (original situation) to residential use. Also, the future expectations to developed new urbanisations in the peripheral areas next to the neighbourhood of public housing.

|

|

|

|---|

Figure 4. Street view in the City-neighborhood “Angelelli” and some houses modified by the inhabitants. By author.

4. Discussion

The results give an account of the form of production of peripheral territories and provide reflections on the evolution of the surroundings close to the state-produced urbanisations in a time period of more than a decade. The cases presented show how location is the central variable for understanding how the relationships of physical-spatial proximity with the urban fabric have been configured (or not), the situations of informality in the forms of access to land and housing, and the degree of vitality or isolation that results from each situation analysed. Also, how the increase in the valuation of urban land near these neighbourhoods evolves, which allows detecting differential processes of territorial appreciation close to state action.

More than 10 years after the implementation of a social housing programme, it has a strong impact on the urban configuration in the periphery of the city, due to the number of housing units built, the scale of the complexes, and the relocation of the vulnerable population. We observe that the form of production of the peripheral territories continues to reproduce an isolated, highly fragmented, disjointed space, with situations of informality and precarious housing that intensify conditions of residential segregation.

In both cases, the value of urbanised land increases, due to the change in land use, (rural–urban). In the case of Angelelli, is registered a very significant increase in the number of times given the consolidation dynamics that it presents. The linkages refer to nearby populous neighbourhoods and a greater demand for location in an urban sector, which, although isolated, recognises links with future urbanisations of private production.

The high value of extensions (new housing units at the back of the lots or in vacant lateral spaces of the house, and in some cases, new constructions on the upper floor) responds to the need to increase the habitable area and solve overcrowded conditions. Additionally, it also responds to the need to have a productive space for income generation while pointing out the difficulties of access to urban land by new households as a result of family evolution.

5. Conclusions

The physical form that shows in the peripheral growth expands by fragments with internal homogeneity, low socio-spatial mixture, and the intensification of social division of space. The public housing policy does not escape this logic. They are inserted as enclaves, with little solution of continuity with the built environment. The isolated location is an expression of inequity in access to land because it is conditioned to the mobility possibilities of individuals. In highly vulnerable contexts, mobility is associated with access to public transport, its frequency, and the possibilities of afford travel costs. In peripheral contexts, access to urban opportunities relates to the right to the city, conditioned to the possibilities of access to mobility and public transport.

The understanding of what type of physical and social environments were produced where the housing complexes materialised by state intervention are located allows us to reflect on the Right to the City in the peripheral territories. On the one hand, these are isolated locations, exempt of urbanity and vitality. On the other, private spaces (homes) highly transformed to respond to vital needs, show high levels of appropriation and acceptance by the inhabitants. The paradox is thus expressed in two scales of intervention: access to urban opportunities and the valuation of private space.

The mercantile logic is evident in the urbanisation process. It is expressed though the valorisation of residential environments with the passing of time, even in highly vulnerable contexts. At the beginning of the process, it is relegated to locate in peripheral areas where the value of urban land is lower. Then it contributes its valorisation, in a process of spatial fragmentation which leaves vacant spaces to speculation. The cases corroborate that state interventions do not attenuate the speculative land market processes since they contribute to increasing the land value urbanising distant areas.

Finally, the importance of studying the environments that are configured with these interventions is mentioned, as well as the processes of consolidation of the neighbourhoods from the action of the inhabitants themselves who show a high dynamism and appropriation of the place of residence and its surroundings.

In the peripheral territories and close to the housing complexes, informal settlements take place. In some cases, they are large-scale planned operations that show how access to the city and housing is presented as a utopia in our cities. The outcomes, in a broader context of urban production, show that it is necessary to advance in the materialisation of inclusive and sustainable residential environments, as well as they promote another type of statal intervention to attenuate inequalities in the territory and promote more lively urban spaces. Recovering the territorial dimension in the design of housing is the starting point for developing more integrated urban configurations, and promoting greater access to agglomeration opportunities within the framework of the right to the city, as a horizon of equity in the future urban development.

References

Acioli, C. (2018) Vivienda y urbanización sustentable e inclusiva en la nueva agenda urbana. Vivienda & Ciudad n. 5, Córdoba, pp. 28–35. Retrieved from: https://revistas.psi.unc.edu.ar/index.php/ReViyCi/article/view/22797

de Mattos, C. (2016). Financiarización, valorización inmobiliaria del capital y mercantilización de la metamorfosis urbana. Sociologías, 18(42), 24–52. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-018004202

de Mattos, C. Link, F.(2015) Lefebvre revisitado: capitalismo, vida cotidiana y el derecho a la ciudad. Santiago. Ril Editores Colección Estudios urbanos UC. 2015.

Falú, A.; Marengo C. (2015) “El Plan Federal en Córdoba, luces y sombras en su implementación: Nuevos programas, viejas soluciones” en libro Hacia una política integral de hábitat. Aportes para un observatorio de política habitacional en Argentina. Buenos Aires; p. 493–523

Fernández Wagner, R. (2015) El sistema de la vivienda pública en Argentina. Revisión desde la perspectiva de los regímenes de vivienda. En Barreto y Lentini (comp.) Hacia una política integral del hábitat. Ed. Café de las Ciudades, pp.29–96

Harvey, D. (2014) Ciudades Rebeldes. Del derecho a la ciudad a la revolución urbana. Bs As. Ed. Akal.

Marengo C. Lemma M, (2017). Ciudad dispersa y fragmentada. Lecturas de forma urbana en emprendimientos habitacionales privados, Córdoba 2001–2010” en Cuaderno Urbano vol. 22. Resistencia. Retrieved from: https://redib.org/Record/oai_revista4304-cuaderno-urbano

Marengo, C., Elorza, A. L. (2018) Segregación residencial socioeconómica y programas habitacionales públicos: el caso del programa Mi casa, Mi vida en la ciudad de Córdoba, Argentina. Direito da Cidade n.10 (3), Brasil, pp.1542-1568 Retrieve from http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/rdc.2018.32765

Marengo C., Monayar V. (2020) Urban Growth, Social-Spatial Inequalities and Housing Policy: A Case Study of Cordoba, Argentina. Urbana - Urban Affairs & Public Policy. Retrieve from: https://doi.org/10.47785/urbana.1.2020

Rolnik, R. (2018) Prólogo. En Hernández, M. y Diaz Garcia V. (Coord.) Visiones del hábitat en América Latina (pp. 7–11). Ed. Reverte, Madrid.

Secchi, B. (2015) La ciudad de los ricos y la ciudad de los pobres Madrid Ed. Catarata.

Soja, E. W. (2010) Seeking Spatial Justice Paperback, University of Minnesota Press.[Spanish versión 2014, En busca de la justicia espacial. Valencia: Tirant Humanidades.]

Svampa, M.; Viale, E. (2014) Maldesarrollo. La Argentina del extractivismo y el despojo. Katz, Buenos Aires.

Zicardi, A. (2015) Cómo viven los mexicanos. Análisis regional de las condiciones de habitabilidad de la vivienda. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, México.

Figures (8)

More details

- License: CC BY

- Review type: Open Review

- Publication type: Conference Paper

- Submission date: 8 October 2021

- Publication date: 23 August 2022

Citation

Marengo, M. (2022). Residential Production and Spatial Inequalities, a Territorial Analysis from the ‘Right to the City’: The Case of Córdoba Periphery. The Evolving Scholar | IFoU 14th Edition. https://doi.org/10.24404/615f9ba0186996000962ba8b

No reviews to show. Please remember to LOG IN as some reviews may be only visible to specific users.