Dialogues, Tensions, and Expectations between Urban Civic Movements and City Administration: Lessons for Urban Political Evolution from Two Recent Participatory Processes in Portugal

This article presents, in a resumed form, our preliminary analysis on the evolutionary framework for new types of intersections, dialogues, and conflicts between urban administrations and civic movements in Portugal. The analysis is based on a conceptual classification spectrum for the characterization and influence of urban movements; and concomitantly on two case studies developed around urban requalification processes in two central public spaces in the cities of Lisbon – the Martim Moniz Square – and Aveiro – the Rossio Garden. In these cases, the conflicts and the interconnections between local authorities and social movements have been evolving through very interesting forms. Expressing not only relevant changes occurring on urban civic movements themselves, but also an inevitable – although still quite limited and visibly thwarted political culture – reconfiguration on urban governments and its administration.

Type of the Paper: Peer-reviewed Conference Paper / Full Paper

Track title: Metropolization and the Right to the City

Dialogues, Tensions, and Expectations between Urban Civic Movements and City Administration: Lessons for Urban Political Evolution from Two Recent Participatory Processes in Portugal

João Seixas 1, José Carlos Mota 2

|

Names of the track editors: Caroline Newton Caroline Newton Journal: The Evolving Scholar DOI:10.24404/616ca02036561a00099446b7 Submitted: 18 October 2021 Accepted: 01 June 2022 Published: 23 November 2022 Citation: Seixas, J. & Mota, J. (2021). Dialogues, Tensions and Expectations between Urban Civic Movements and City Administration. Lessons for Urban Politics Evolution from Two Recent Participatory Processes in Portugal. The Evolving Scholar | IFoU 14th Edition. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY (CC BY) license. ©2021 [Seixas, J. & Mota, J.] published by TU Delft OPEN on behalf of the authors. |

|---|

1 NOVA FCSH 1; jseixas@fcsh.unl.pt; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4948-9113

2 University of Aveiro 2; jcmota@ua.pt; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8953-2027

Abstract: This article presents, in a resumed form, our preliminary analysis on the evolutionary framework for new types of intersections, dialogues, and conflicts between urban administrations and civic movements in Portugal. The analysis is based on a conceptual classification spectrum for the characterization and influence of urban movements; and concomitantly on two case studies developed around urban requalification processes in two central public spaces in the cities of Lisbon – the Martim Moniz Square – and Aveiro – the Rossio Garden. In these cases, the conflicts and the interconnections between local authorities and social movements have been evolving through very interesting forms. Expressing not only relevant changes occurring on urban civic movements themselves, but also an inevitable – although still quite limited and visibly thwarted political culture – reconfiguration on urban governments and its administration.

Keywords: Civic movements; Participation; Governance; Cities

1. Introduction – Recent trends in Portuguese urban politics

Cities have become the epicentre of most of humanity’s major issues, from climate change to social inequalities, from the dilemmas of the digitalization of the economy and urban life, to the formation of new cultures, identities, and communities. This represents an evolution which is leading to an increasingly active combination of crises, pressures, experimentations, and expectations.

In most of Europe’s urban territories, after several decades of continuous growth mainly associated with metropolitanisation and urban dispersion, new trends in uses and experiences are now spreading with a growing spectrum of individuals, institutions, and companies assimilating differentiated habitat experiences, working capabilities, mobility, and consumption habits (Sennett, 2016).

These changes are having a strong impact on the fields of urban politics (Merrifield, 2013), especially in terms of the cultures and dynamics of urban government institutions, there are developing different paradoxical realities. The overlaps of several initiatives, proposals, and innovative trends are becoming increasingly visible with organizational and cultural structures that remain considerably classical and bureaucratic, as well as mostly dependent on internal or partisan stimulus. Overlaps that often develop into quite fragmented and unstructured results. Notwithstanding the growing positioning of a vast myriad of innovative strategic and political approaches, it propagates the feeling of the limitations in the capacity building and governing action of several urban governance domains in the face of the challenges before them. These feelings and questions develop, in turn, political reactions that allow the promotion of localist and even populist views.

In Portugal, these structural – and growingly paradoxical – developments are also occurring, combining global trends with specificities arising from an urban culture that historically has been poorly understood by society and policymakers (Seixas et al., 2019). The current dilemmas facing Portuguese cities and metropolises are strongly conditioned by the combination of structural weaknesses – particularly in terms of the limited capacities and resources of local authorities, in one of the most centralized countries in Europe – with a long period of socio-economic crisis and the resulting austerity policies. Even after the hardest austerity period, followed by a few years of some economic and social improvement, the majority of the main political and regulatory local systems have been maintained (Teles, 2015). They have become increasingly out of step with old needs and new challenges, and most notably on fundamental urban dimensions, such as the current pressing housing and real estate market realms.

This article presents a preliminary analysis on the evolution of new types of intersections, dialogues, and conflicts between the urban administrations and civic movements in two Portuguese cities. Two case studies were developed, concerning urban requalification processes in two major public spaces in the cities of Lisbon and Aveiro. In both cases, the conflicts and the interconnections between local authorities and social movements have evolved in some form, expressing the changes occurring on urban civic movements, as well as the still limited political culture reconfiguration on urban governments.

2. Urban social movements in Portugal

Social movements organised around urban issues have a long history in European cities. The right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968; Harvey, 2008) is perhaps one of the most relevant perspectives that still inspires the debate about living in the city and the right to housing. In the 1970s, newly environmental and public space qualification movements emerged, influenced by the energy crisis as well as by mobility and safety. Afterwards, collective associations mobilised for the protection of built heritage, stimulated by international organisations such as UNESCO. Recently, a new generation of social movements has emerged that are concerned with the city and its transformation, in response to the crisis of traditional information practices, the erosion of state regulation, and the emergence of global economic actors with power to control decision processes – a situation amplified by the 2008 financial crisis (Mayer, 2009).

Focusing on this latest area of study, there was a convergence of interventions in the city by groups of citizens that appeared through the emergence of a social and environmental awareness of collective life in the city, and acting through the dissemination of technologies from multicultural and connected urban contexts. There is a fundamental motivation that characterises these groups which transcends the markedly ideological or corporate dimension of previous generations, referring them to an action focused on the city as the object and its core elements (the neighbourhood or the street), as the focus of concerned collective forms of organisation, in response to a change in the scale of the functioning and autonomy of local, public associations. Finally, the performance of these recent social movements stands out for its growing technical-scientific robustness, articulating the focal concerns of reflection with collective action (Hamel et al., 2000).

Most of these social dynamics happen when there are combined reasonable densities of sociocultural critical mass, the influence from qualified professions, and some sort of public support (Subirats, 2016). And now, with the development of the new crisis, urban landscapes of wider economic difficulties, qualified unemployment, and growing social and spatial inequalities. Most of the time these civic pressures were triggered by contesting actions of city governments and their public administrations. But, there is a widespread nurturing, particularly in the urban tissue and from younger generations, in the main Portuguese cities and their vast metropolitan territories, of new cultures and forms of exercising civic politics and much more participated, transversal, collaborative, and committed practices. They emerge with strong dynamism and social attention, although with a still relatively fragile capacity for political influence. Despite having been fostered mainly from reactive and protest dynamics, these new practices have demonstrated new propositional and organisational capacities, specifically around more urgent dimensions, such as accessibility to housing, social inequalities, and the quality of public space.

Although these civic dynamics have been primarily fostered through reactive expressions and protesting, they are now demonstrating new propositional and organisational capacities, most notably around most pressing dimensions such as housing accessibility, social inequalities, sustainable mobility and the quality of public space. A widespread nurturing of these movements can be understood, particularly in the denser urban territories, with a dynamism mostly geared by younger, qualified, and digitally connected generations.

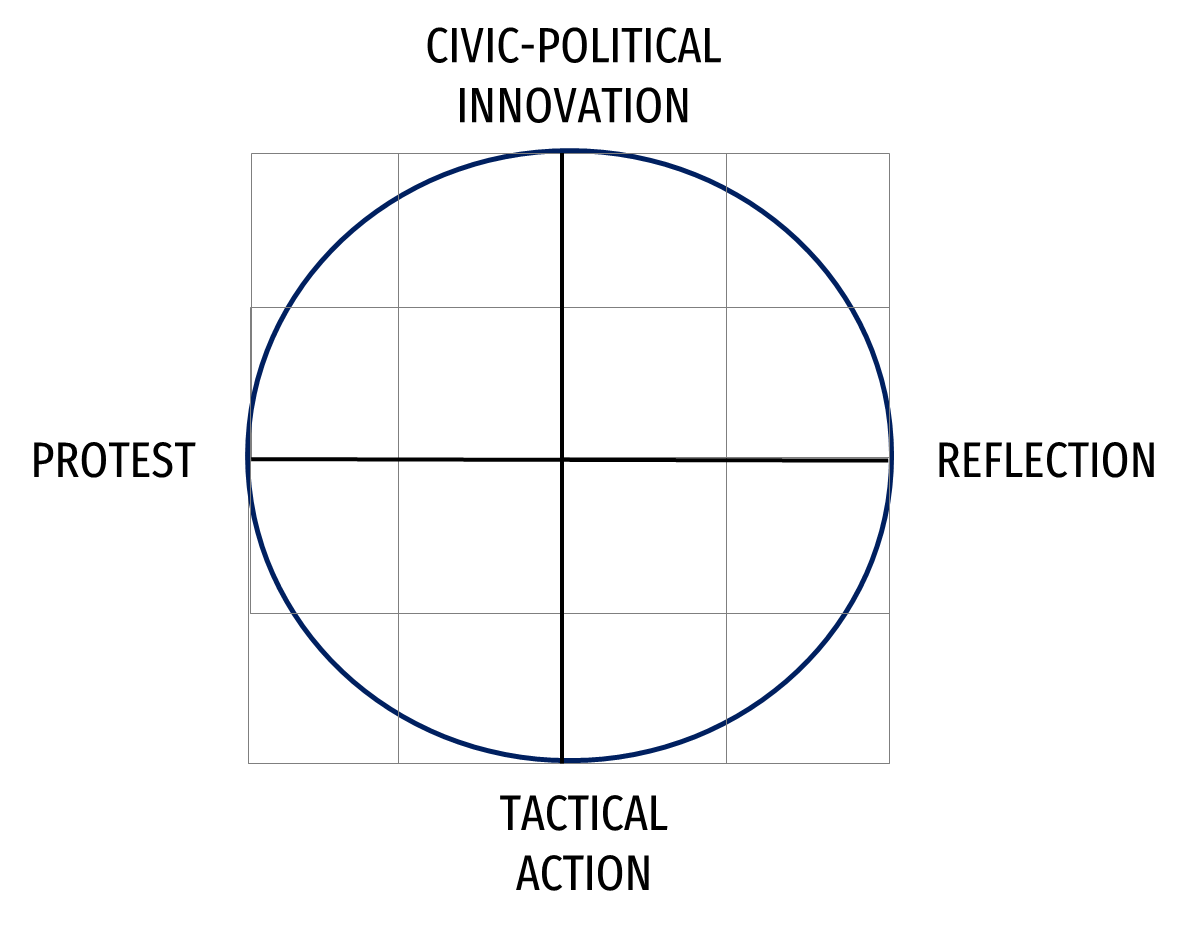

Even so, it is possible to identify different types of movements, depending on their main characteristics, as their fundamental motivations, resources, forms of organisation and networking, cultures and practices, and corresponding results. In this sense, we propose a classification spectrum for the characterisation, dynamics, and influence of urban movements, according with four types of overall typological cultures and characteristics: (i) protest, (ii) reflection, (iii) tactical action, and (iv) civic-political innovation (Diagram 1). Protest-type movements traditionally have a reactive stance on a given issue, whether it is an urban problem or an intention to transform the city, and organise themselves to influence the decision-making process, namely through petitions, interventions with media impact, and, in some cases, legal initiatives. They expect short-term results and mostly exhaust their action with the end of the cause. Its relationship with political power is tense and often conflicting (Mota & Santinha, 2016). Urban social movements mostly driven towards a reflection culture, conversely, are motivated by knowledge and diagnosing and generating ideas about the future of the city, for which they organise debates and forums, producing opinions, and only then taking positions. They do not tend to act in the short term, and exist a bit farther from the media’s influence, having higher potential, although mostly through codified and modest ways, to build bridges between antagonistic positions (Mota, 2014). Tactical action movements are mostly motivated by the transformation of cities and public space through guerrilla urbanism or tactical urbanism actions. They intend to drive or achieve transformation through specific, low cost, and visible impact initiatives, desirably through participatory processes (Lydon et al., 2015). Finally, the much rarer civic-political innovative structures or movements, emerge – or evolve – in response to the rise of civic, administrative and political responsibilities, promoted by a growingly demanding citizenry and/or by politicians and public administration requiring or suggesting co-governance actions or programmes. Their aim turns out to be the development of new models for cooperation within public policies and citizen action, promoting the prototyping and design of new/experimental governance solutions. The new experiences of the Citizen laboratories can be proposed as processes or instruments for the development of these types of movements (Parra, Fressoli & Lafuente, 2017).

Diagram 1. Typology spectrum for urban social movements. Source: authors

The composition of the various movements of an urban system, with their respective characteristics, dynamisms, and results, is not evidently linear, orderly, or integrated. The several movements in a city do not work in a watertight way, although influencing each other, and often forming common civic ecosystems of combined action that aim to inspire and influence others. Even when they do not work in the same geographical area of influence, they take advantage of their network capacities, knowledge, and experience. Several aim at breaking down classical barriers and supporting new contexts of greater cooperation between local governments, public administration, and civil society (Polyak et al., 2021). Naturally, the emergence of civic groups stems from a limited framework of dialogue between public authorities and citizens, the lack of a shared vision for the future of cities, and the emergence of specific projects without a planning perspective which reflects opportunities for public and private investment (access to European funds or real estate projects).

Following this resumed conceptual framework, an empirical analysis focused on two processes of urban public space requalification (in the cities of Lisbon and Aveiro) and the correspondent civic positioning and expressions, was developed.

3. Two case studies of urban requalification (Lisbon and Aveiro)

3.1. The Martim Moniz square in Lisbon

Martim Moniz square (MM) is one of the most important public spaces in the city of Lisbon. In this large square, there is a rare combination of important urban values, from its central geographical positioning to a significant landscape amplitude and a quite evident urban and intersectional potential (Figure 1). Furthermore, involving MM pulses a rich and diverse social and economic dynamism, thus conjugating a set of remarkable and unusual characteristics making this square a fundamental hinge space for the whole city of Lisbon.

Figure 1 & 2. The Martim Moniz Square in Lisbon, and proposed project for the MM Market (later rejected). Source: CML

Lisbon is increasingly cosmopolitan and integrated in global avant-garde trends, and has distinguished itself in recent years by a rapid process of change. The coexistence and the confrontation is strongly visible between several processes of innovation and change, and with a parallel structure of new types of inequalities and segregation. Today, these dilemmas take place in several domains, and most notably in fundamental urban elements such as access to housing, economic shifts, ecological pressures, and in cultural and communitarian reframing. In view of the vertigo of change and an also growingly visible unbalanced capacity for political regulation, the risks of loss of both social and political perspectives have become notably evident. These risks are particularly expressive around the historical and central territories of the city, where MM is located. The historic centre of Lisbon is today the scene of crucial confrontations and constant imbalances between the “city for the visitors and occasional consumers,” and “the city for the residents and everyday inhabitants.”

Growing appeal for a qualified green area in MM has existed for several decades. Until recently, however, most of the requalification proposals have been commercial in nature and implemented through quite limited and unsuccessful public-private partnerships. With time, as well as with the new urban pressure, MM and its almost timeless expectant situation became an inevitable point of political confrontation. At the end of 2018, the municipality announced its intension to extend the commercial concession contract with the previous promoter (of a Fusion Market in force since 2012, planned until 2022 and in serious decline for some time), extending it until 2032 and now including a commercial requalification of the square with an open shopping centre with about 40 stores, renamed Martim Moniz Market (Figure 2).

The social reaction to this decision was immediate. The citizens – and several movements – complained not only for the ever-forgotten green space, but also that the new commercial pole would have a great impact in terms of ephemeral and touristic pressures and growing concerns on noise and insecurity.

At a following town hall public meeting, the city mayor started to admit that the solution for MM was the ideal. Unleashing a growing chorus of criticism from various parties, both in the chamber meetings and in the municipal assembly, it now also focused on the lack of transparency of the process and on legal incongruities. Meanwhile, at a public meeting organised by the local district, where the councillors as well as the concession entrepreneurs were present, the vast majority spoke out against the project and in favour of a qualified green area. In March 2019, a new movement called ‘Jardim Martim Moniz’ was born, aiming to bring together independent voices, as well as clearer information and decisive influence upon the whole process. At the end of April, a civic petition for an urban garden in MM with almost 2,000 signatures was delivered to the municipal assembly. At the same time, the local district of Santa Maria Maior publicly rejected the market project and demanded a square for residents.

Confronted with the growing civic and political opposition and with the corresponding mediatic debate, the municipality eventually approved the termination of the contract. The decision gave rise to a compensation to the promoter; triggering a completely new process. This process started with a highly concerted effort to listen to the population, through several forms (historical and socio-geographical information, extended surveys, focus groups, and meetings with the civic movements). This new process was organised with external scientific support and extended through different phases. The most mentioned responses clearly pointed at increasing green areas, noise reduction, improvement in pedestrian access, and soft modes of mobility. Also mentioned were other relevant issues, such as a diversification of multicultural activities, more spaces for children and intergenerational meeting areas, and an increase in urban safety. Several preliminary proposals coming from various citizens were also publicly presented (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Some of the proposals developed by participants in the recent public auscultation phases. Source: CML

From the listening phases, and in conjunction with the municipal strategies, a new set of principles were listed for the future of MM and for the definition of the preliminary programme for a future requalification project. At a town meeting in May 2021, the participative report and the guidelines for the preliminary programme were approved unanimously. The municipality thus began the process for an international public tender, stressing the desire to enable innovative solutions. However, and notwithstanding the notable change in the city's urban planning practices in this specific case, this new process could still be understood as dominated by a municipal culture of considerable control on the participatory processes and correspondent directions and decisions. Although heard, the movements were called only on the presentation moments on the final steps of each phase. This administrative and political attitude still does not guarantee a fundamental change in urban management practices by the municipality.

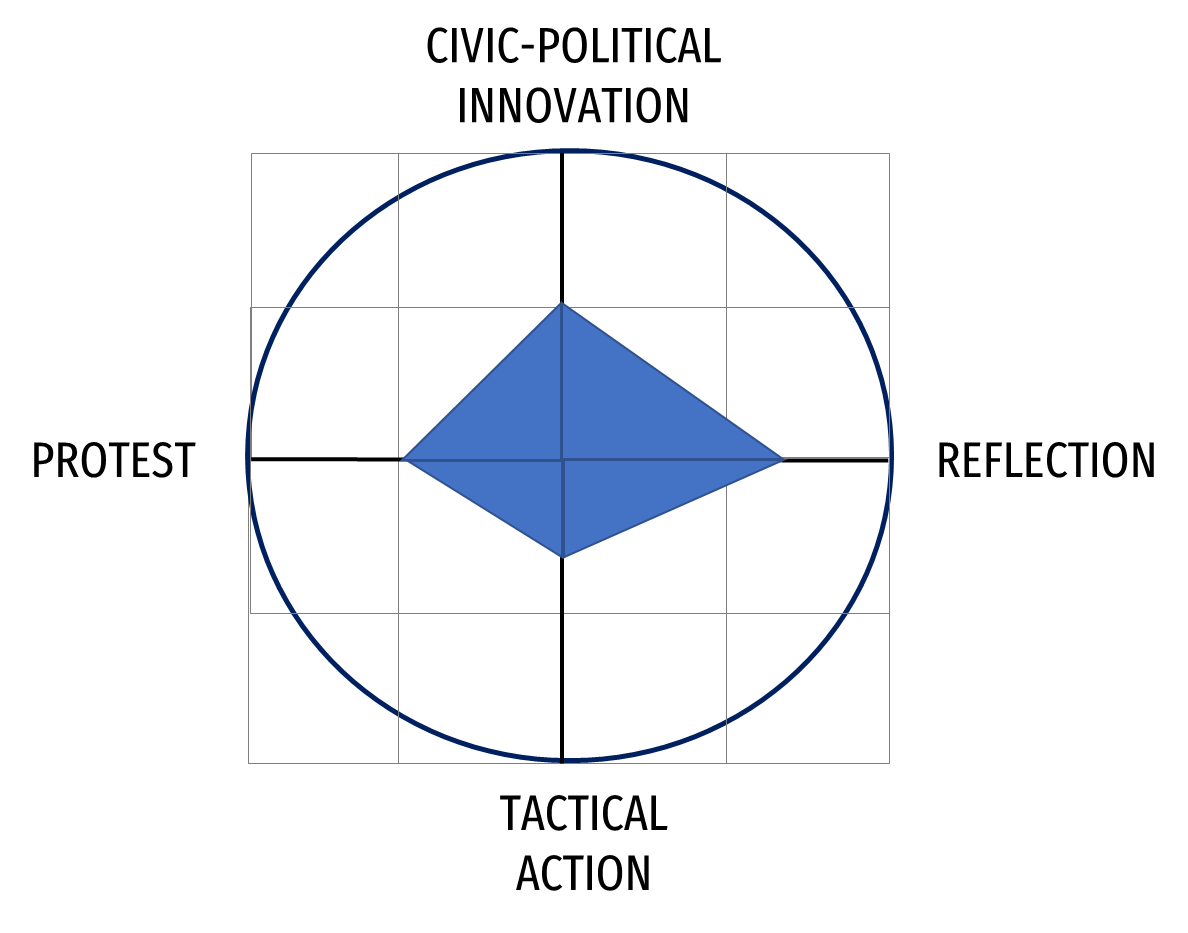

Diagram 2. Typology spectrum for the Martim Moniz urban movement. Source: authors

Therefore, and according to the spectrum previously proposed for the analysis of urban social movements and its influences in local urban governance, Diagram 2 shows, in our view, the main characteristics and evolutionary perspectives corresponding to this case. Having started on a protest base against a contested municipal decision, and developing certain tactical actions, the movement has developed mainly in reflexive terms. The movement subsequently succeeded in getting the local government not only to change its initial decision, but also initiated a new process with greater popular participation. Nonetheless, this public movement has not yet achieved guarantees on the configuration of sustained structural changes from the part of the local administrative cultures.

3.2. The Rossio garden in Aveiro

Rossio is an iconic place in the heart of the city of Aveiro, located between the Bairro da Beira Mar and the central water channel. It has two purposes; it is the only garden serving the surrounding neighbourhood, and is the space where the city’s most important collective events take place.

Today the Garden, due to lack of maintenance, has several problems that need to be solved. There are five fundamental problems: the need to clean and conserve the green spaces, urban furniture maintenance; tree species (palm trees); car parking in the surrounding areas, making the relationship between the garden and the neighbourhood difficult; social problems related to some of the user types; and, an imbalance between tourists looking for boat trips and residents looking for the enjoyment of the existing green space.

The requalification project for Jardim do Rossio in Aveiro emerged within the scope of the urban development operations that the Municipality of Aveiro integrated into the Strategic Plan for Urban Development of the City of Aveiro as part of the application for European Funds. The aim of “transforming [Largo do Rossio] as the great central public space of the city, stimulating its pedestrian use and providing it with functionalities for the realisation and organisation of various events in the City,” (...) providing “this space with a subterranean car park, which will be the object of a construction and operation concession tender.”

Figure 4 & 5. Rossio Garden Projects – phase 1 and 2. Source: Municipality of Aveiro

The project received criticism related to the destruction of the existing garden and the construction of an underground car park, even though it was intended to partially replace the existing parking on the surface. In addition, there are several alternative car parks in the vicinity which aren’t used to their capacity. The underground car park option has a fundamental contradiction with the program that finances the operation, since it aims at contributing to sustainable urban development and the decarbonisation of mobility. These aims are apparently related to the financing entity of the operation. Furthermore, the project contradicts the mobility principles advocated for the city, namely the existing technical studies. Also, the commitment to an event venue increases the fears of worsening the acceleration of tourist attractiveness factors, in line with what has happened in recent years with the growth in the offer of local accommodation, and reducing the functions that support daily life, namely for the residents of Bairro da Beira-mar (Figure 4).

The intervention also raised fears about the alteration of the water table in the surroundings, which could affect the old building of Bairro da Beira-mar that is supported by wooden piles. As well, the felling of all the trees was much criticized as “they play an essential role, both in terms of an environmental point of view and of urban comfort.”

The choice of the modality of a call for ideas for designing and planning that space was also criticised, as this instrument is an exercise in which the designers respond to a specification that they cannot contradict, they spend limited time researching (which does not allow them to gain knowledge of the object they want to transform) and do a job without any contact with the local authority and the community.

The lack of a participatory process and the impact of the solution generated a huge civic controversy that gave rise to various types of civic movements, as referenced before. The protest movements organised petitions, several public events, which were highly attended, and legal initiatives. The reflections movements promoted public debates and made relevant technical recommendations.

Despite not having backed down on one of the critical issues – the car park – the municipal executive made significant changes to the initial proposal (Figure 5). It increased the green area, reduced the area of the event square, reduced and reformulated car traffic provisions, and resized the sidewalks along the urban façade. Even so, to respond to the need for access to the garden, the Municipality is still proposing to build a new access bridge through the lock zones (next to the estuary) which will certainly increase car traffic pressure in the Rossio area. From the initial project budgeted at seven million euros, the work was awarded for 12.4 million euros, in a concession contract that also involves the management of another car park in the city, plus up to 1.2 million euros for the second bridge.

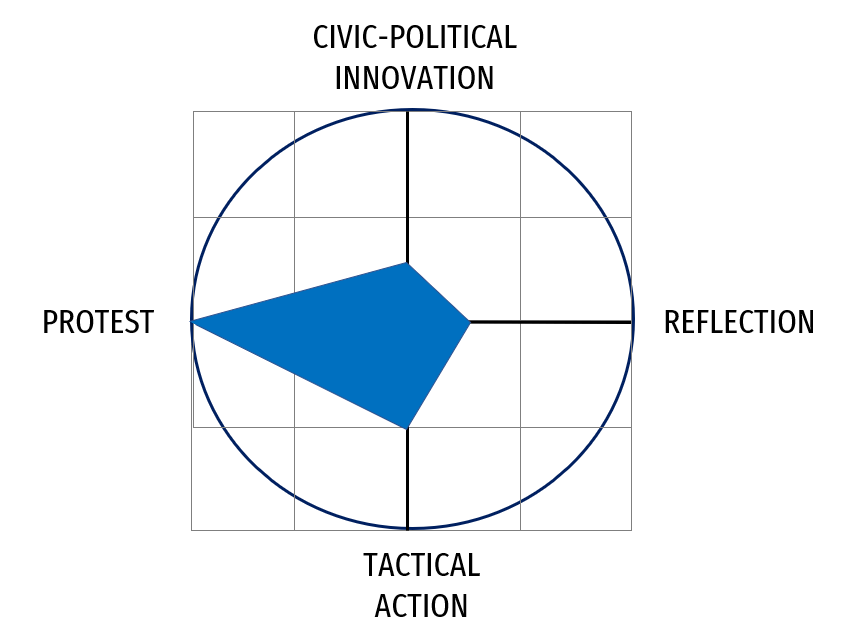

Diagram 3. Typology spectrum for the Jardim do Rossio urban movement. Source: authors

Following the proposed spectrum, Diagram 3 expresses the predominance of a protest nature for the Jardim do Rossio movement, including its high intensity and duration, sustained in some tactical actions of occupation of public space. The reflection, as well as the wider correspondent civic and political innovation dimensions, had some sort of dynamism – although not at all showing structured forms of capacitation. The outcomes of the actions from this, as well as from other collectives in Aveiro led the local government to partially change its attitude and proposal, although these changes were not directed to the desired dimensions. More recently, the involvement of the collective in the municipal electoral process (in September 2021), being associated with a specific opposition party and without a victorious result, adds uncertainty in the prediction of its future evolution and correspondent ability to influence local politics.

4. Discussion & Conclusions

Our research, here presented in a very concise form, has identified a set of key fields for an expanded interpretation on the recent evolution of Portuguese urban civic movements and the corresponding urban governance attitudes. It not only concerns the more specifically focused urban planning and regeneration processes, but also around possible cultural changes developing on the political and institutional structures of local government, as well as in the evolution of urban movements themselves and correspondent socio-political and civic cultures.

The two case studies presented here show that some decisive lines framing the evolution of urban governance, and are based on the activation of formal, as well as informal intersection processes in the local policy debate, confrontation, and production. This is most notably the case when considerably distinct groups and universes are involved, in a setting with very little history of encounter and dialogue.

On one side, these two case studies show an interesting evolution in the influence capacity of civic movements. The initial plans of the municipalities were changed due to the civic pressures clearly demonstrated. On the other side, however, the decision-making processes themselves are still not clearly open and participatory mechanisms. Which seems to demonstrate that although the urban political power is becoming more sensitive to the pressures of civil society, what is changing within the political-administrative structures is not yet a structural process of connection and dialogue with each city’s communities. It is manifest that there is still a long way to go in the reduction of entrenched dichotomies established over several decades, and in promoting a culture of more permanent communication between the different urban actors.

Overall, there are still several governance fragilities that are quite visible, decisively influencing the ways in which the transformation of the territory is processed, without a clear foundation in public policy principles – local, national, and European – and without a due and timely civic involvement. The dialogue between urban local administrations and citizens, when it takes place, is almost always when it is pressed and stimulated by the latter. In one case opening, a new although still unstable participatory process (Lisbon), and in the other still clearly showing little willingness to properly position the citizens’ perspectives, using the argument of political legitimacy (Aveiro).

Nevertheless, both cases also show the growing role of protest movements in Portuguese cities, with growing impact in both the media and in institutional contexts. This growth of protest movements has provided incentives to the development of more reflective postures, thus contributing to both the qualification of the debates and to an expected improvement of future processes of dialogue, and possibly to some forms of collective construction cultures. This analysis demonstrates the gaps, but also the potential and richness of the growing interrelationship between the social movements in the city and the local political institutions.

References

-

Hamel, P. (2000). Urban Movements in a Globalising World. London: Routledge.

-

Harvey, D. (2009). Social Justice and the City.

-

Lefebvre, H. (1972). Le Droit à la ville: Suivi de espace et politique. Paris: Éditions Anthropos.

-

Lydon, M, Garcia, A., & Duany, A. (2015). Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change. Washington: Island Press.

-

Mayer, M. (2009). The 'Right to the City' in the Context of Shifting Mottos of Urban Social Movements. City, 13, 362–374.

-

Merrifield, A. (2013). The Urban Question under Planetary Urbanization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 909–922.

-

Mota, J.C.; Santinha, G. (2016). “Aveiro: Civic Movements to Promote Smarter Decisions for the Future of the City,” en Human Smart Cities. Springer International Publishing. 2016, pp.219–227.

-

Mota, J.C. (2014). "Planeamento do Território: Metodologias, Actores e Participação.” Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade de Aveiro

-

Nel·lo, O. (2015) La ciudad en movimiento. Días & Pons, Madrid.

-

Parra, H.; Fressoli, M.; Lafuente, A. (2017). “Dossie: Ciência Cidadã e Laboratórios Cidadão/Citizen Science and Citizen Labs (pt/en/es)”, en LIINC EM REVISTA, v. 13, p. 1, 2017. http://revista.ibict.br/liinc/issue/view/244

-

Polyak et all, (2021). The Power of Civic Ecosystems. Cooperative City Books, Vienna, 2021

-

Seixas, J. & Guterres, A.B. (2019). “Political Evolution in the Lisbon of the Digital Era. Fast Urban Changes, Slow Institutional Restructuring and Growing Civic Pressures” Urban Research and Practice, volume 11, issue 3.

-

Sennett, R. (2016). Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City. Allen Lane, London.

-

Subirats, J. (2016). El poder de lo próximo: las virtudes del municipalismo. Los libros de la catarata, Madrid

-

Teles, F. (2015). The Distinctiveness of Democratic Political Leadership, Political Studies Review, Vol 13(1): 22–36

Figures (8)

More details

- License: CC BY

- Review type: Open Review

- Publication type: Conference Paper

- Submission date: 17 October 2021

- Publication date: 23 November 2022

Citation

Seixas, J. & Mota, J. (2022). Dialogues, Tensions, and Expectations between Urban Civic Movements and City Administration: Lessons for Urban Political Evolution from Two Recent Participatory Processes in Portugal. The Evolving Scholar | IFoU 14th Edition. https://doi.org/10.24404/616ca02036561a00099446b7

No reviews to show. Please remember to LOG IN as some reviews may be only visible to specific users.