Assessment of Knowledge, Perception, Attitude, Risk Factors Prevention, and Treatment Options of Cancer among Natives in Elgon Sub-Region, Uganda

Article Information

Ali Kudamba1, 2*, Shaban A Okurut2, Hussein M Kafeero1, Hakim Nsubuga3,4, Abdul Walusansa1, 2, Jamilu E. Ssenku2

1Faculty of Health Sciences, Habib Medical School, Islamic University in Uganda, Kampala

2Faculty of Science, Department of Biological Sciences, Islamic University in Uganda, Mbale

3Faculty of Science, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Islamic University in Uganda, Mbale

4Faculty of Science, Department of Chemistry, Muni University, Uganda

*Corresponding author: Ali Kudamba, Faculty of Health Sciences, Habib Medical School, Islamic University in Uganda, Kampala.

Received: 17 July 2022; Accepted: 28 July 2022; Published: 20 August 2022

Citation: Ali Kudamba, Shaban A Okurut, Muhammad Lubowa, Jamilu E. Ssenku, Abdul Walusansa, Hasifah Nanyingi, Muhamad S. Mubajje, Twaha Abiti and Hussein M Kafeero. Assessment of Knowledge, Perception, Attitude, Risk Factors Prevention, and Treatment Options of Cancer among Natives in Elgon Sub-Region, Uganda. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences 5 (2022): 472-487.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Globally, cancer is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality and most cancers are due to infections and so, are preventable. Earlier studies revealed that several cancers could be preventable through intensified healthcare education but there is limited information in regards to the Elgon sub-region. Therefore, our study was aimed at assessing cancer indigenous knowledge among natives in the Elgon sub-region.

Method: Mixed methods research design was adopted. A total of 73 participants, selected through the snowball sampling technique were involved. Data collection was done through pretested questionnaires. MedCalc version, 20.008 was used for data analysis, and results were presented in tables and figures.

Result: The majority of the study participants were males (58%), aged between 46 – 55 years (58%), Ugandans (90%), and married (67%). Most of them had inadequate knowledge about cancer (p<0.05) and highlighted sores that slightly heal at any body parts as well as blood in feces as putative predictors of cancer infection (p<0.005). A total of nine cancer types were documented and cervical was the most prevalent (p<0.0001). Smoking was the most pronounced cancer-associated risk factor (p<0.0001) and avoiding smoking was perceived as the major prevention option (p<0.0001). No cancer treatment options in cancer treatment cited in this area (p<0.172).

Conclusion: The natives had limited knowledge and poor perception of cancer due to low literacy levels. Therefore, there is a need to intensify cancer health education programs through word of mouth and radio talk shows. The plant medicinal plant used in cancer treatment needs to be documented.

Keywords

Cancer; Indigenous Knowledge; Interventions; Medicinal Plants; Signs and Symptoms; Treatment Options & Cancer Conventional Drugs

Article Details

1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death among the global population with 9.6 million deaths and every 1 in 6 deaths is due to cancer [1]. About 70 % of the documented cancer deaths occur in low and middle-income countries including Uganda [1]. The reports on cancer incidences and deaths in 2018 revealed an estimate of 752, 000 (4 %, global burden) and 506, 000 respectively in Sub-Sahara Africa, peculiarly cervical, breast & prostate cancers [2]. In a related development, in 2018 GLOBOCAN reported 32617 cases and of which 21829 scumbled to deaths in Uganda [3]. Moreover, an earlier study conducted on the cancer incidences in Kampala over the previous two decades revealed a rapid rise in this deadly disease, particularly breast cancer in females and prostate cancer in males [4]. The actual number of cancer cases and deaths in the Elgon sub-region is difficult to establish due to the lack of a regional cancer registry. Therefore, under such circumstances underestimation of these incidences cannot be ruled out. However, informal interviews with health workers at Mbale Regional Referral Hospital revealed an annual rise in the case of this deadly disease. The rise in cancer incidences has been associated with risk-associated activities like smoking, excessive body weight, genetic factors, familial polyposis, alcohol, low physical activity, and ulcerative colitis and this has been worsened by the adoption of western lifestyles [1,5,6]. Studies by [7] have shown that the adoption of western lifestyles amongst Uganda’s population is on the rise and with this globalization phenomenon, Sironko & Bulambuli districts may not be exceptional. It was also further highlighted that 50 % of cancer diseases could be preventable through understanding cancer risk-associated factors and prevention interventions [8]. Cancer healthcare education on basic knowledge & perception, comprehending risks associated and early detection have also been cited as some of the key cancer prevention strategies [9]. However, studies on knowledge, perception, attitude, cancer-associated risk factors, and prevention & treatment options among natives in Sironko & Bulambuli are rare. Therefore, the current study investigated knowledge, perception, attitude, cancer risk factors, prevention, and treatment option among natives in Sironko and Bulambuli districts. Furthermore. Previous studies showed that good knowledge, proper perception, and a positive attitude toward cancer and its associated risk-associated behaviors were deterring factors to cancer prevalence among different communities all over the globe [2]. However, such studies specifically on knowledge, perception, attitude, cancer-associated risks factor, and prevention & treatment options in Sironko and Bulambuli districts are rare and so are paramount to an investigation. Therefore, our study investigated, knowledge, perception, attitude, and cancer risk-associated factors among local communities in Sironko & Bulambuli districts.

2. Methodology

2.1 Study Area

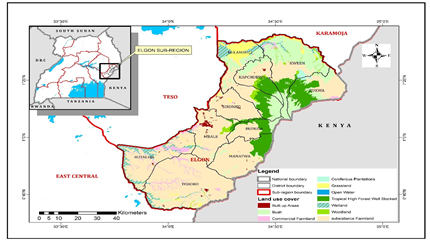

The study was carried out in Sironko and Bulambuli districts. These districts are located within the geographical coordinates of 1’17 N &1’24 N and 34’15 E & 34’45 E respectively and lie at an average elevation of; 3996 ft (1,218 above sea level (Google Map, 2020). Sironko and Bulambuli are 24.7 km & 55. 4 km respectively from Mbale city and 275.9 km & 306.8 km respectively from Kampala, the Capital city of Uganda (Figure 1). The study was conducted in a total of eight peri-urban towns & trading centers in the Sironko and Bulambuli districts. These included; Sironko, Budadiri, Buweli & Mutufu Town Councils in the Sironko district and Bulambuli, Bulengenyi & Buyaga Town Councils & Zema Trading Centre in the Bulambuli district. These villages were chosen because our preliminary studies revealed that rising cases of cancers in this area based on in-depth interview from the local leaders. But, information on knowledge, perception, attitude, risk factors prevention, and treatment options in regards to native in Elgon sub-region is scanty and so was worthy an investigation.

2.2 Selection of the Study Sites

We conducted a reconnaissance survey in our study area between January to February 2021. The study sites were selected based on the cancer statistics index obtained from Mbale Regional Referral Hospital reports for the previous decade (2010-2020) and as well on the advice of the District Health Officer (DHO) of the respective districts of the study.

2.3 Study area

The area has a total population of 1.12 million people representing 4.8 % of the total Uganda population [10]. The total residential occupants in Sironko and Bulambuli are 242,422 and 174,508 respectively as per the 2014 National Population and Housing Census [10]. The main tribe is Bagisu who are mainly peasants, and it is the 7th largest ethnic group in Uganda [10].

2.4 Study Design

The study was a cross-sectional survey with both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection, presentation, and analysis [11].

2.5 Study Population

The study population comprised all natives in Sironko and Bulambuli who had ever been diagnosed positive for cancer or had experienced cancer patient(s) in their family history. The target population was Lumasaba-speaking residents above 25 years and this age was selected because it was considered a maturity age and responsible so gave reliable content on the topic under investigation [12].

2.6 Selection of Participants and Sampling Technique

The sample size was calculated from the Cochran formula at a 95 % confidence interval;

S= Z2*P*Q/E2 o(S = Z2[P(1-P)]/E2) where (Q = 1-P)

where S = sample size, Z = standard error for the mean = 1.96 at 95 % confidence level, P is the estimated prevalence or proportion ratio of natives with cancer knowledge in Eastern Region as previously determined by [13] = 95 %, (Trasias et al, 2017) E = Tolerable sampling error/ precision, = 0.05 at 5 % significant level

Sample size = 1.962[0.95(1-0.95)/0.052 = 73

We selected a convenient sample of 73 participants (42 males and 28 females) participants with the help of local leaders (LCI chairpersons) who are the gatekeepers to the local communities. We sampled the eligible participants through the snowball sampling technique. Eligible participants included men and women 25 years above, who had lived in the study area for above 18 years and were conversant with the local language (Lumasaba). We excluded participants with communication challenges, those below 25 years, with confirmed diagnoses of mental illness, and without experience of patients’ cases in their family history.

2.7 Data Collection

Pretested self and researcher-administered questionnaires comprising of both close-ended and open-ended questions were adopted for data collection. The questionnaire was comprised of four sections; demographic data, knowledge & perception, cancer-associated risk factors, and prevention & treatment options. The questionnaires were prepared in the English language but were translated into Lumasaba, to be easily comprehended by the locals and so the validity of the content was ensured. Self-administered questionnaires were collected back from the respondents, two days from the time they were served. This gave the participants ample time to comprehend the items in the questionnaire and so gave valid and appropriate responses. On the other hand, for researcher- administered questionnaire, the responses were instantly recorded as they were being generated, and at the end of each session, they were immediately filed by the respective interviewer. This saved time and as well ensured the safety, validity, and completeness of the data.

2.8 Data Management

Checking and crossing-checking were done on the filled questionnaire for completeness and consistency before data processing and analysis were done as per the procedures previously described by [14]. All the collected data were assigned codes only known to the research team to ensure confidentiality and integrity of the participants’ responses. Hard copies of the data from the questionnaires were kept in locked file cabinets and all the data were reported as anonymous without referring to the specific identifiers of individual clients.

2.9 Data Analysis & Presentation

2.9.1 Quantitative Data Analysis: The collected data was cleaned and entered into Microsoft excel and was exported to MedCalc version 20.008 for analysis, where the frequency tables and figures were generated for easy interpretation.

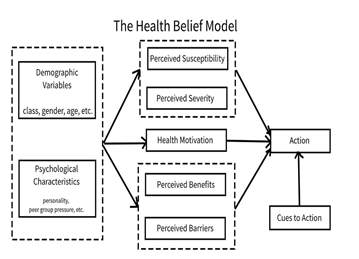

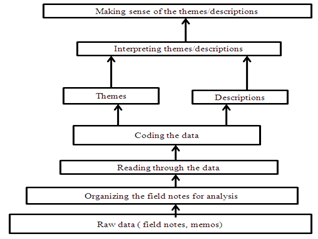

2.9.2 Qualitative Data Analysis: Qualitative data was analyzed following the procedure previously described by [15,16] who contend that data analysis and collection must be a simultaneous process in qualitative research. The field notes from the focus group discussions were used and analysis was done along with the data collection after every focus group discussion (FGD). In total, four FGDs, each taking a maximum of 40 minutes were conducted and designated as FG1-4. The data was analyzed for three themes which included knowledge, perception, attitude, risk factors, prevention, and treatment options. Themes were intertwined within the theoretical model of the Health Belief Model (HBM) that informed our study. The theoretic model adopted in this study was designed by Hochbaum (1958) and Rosenstock (1960) and cited in Health Behaviour & Health Education book [17] as summarized in the fig. below.

The 7 steps of the linear hierarchical approach building from the bottom to the top were used in the analysis (Figure below). For content validity, several methods including observing the participants during data collection were done. For reliability of the content, the field notes were consulted all the time when making the analysis and compiling the research report.

3. Results

The varied and interesting responses were analyzed by use of SPSS and were presented in table and figure forms for easy interpretation.

3.1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics

A total of 73 respondents who were all permanent residents of Sironko and Bulambuli district and of which 58 % were males while 42 % were female participated in the present study.

|

Characteristic |

|

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

Gender |

Male |

42 |

58 |

|

|

Female |

28 |

42 |

|

|

|||

|

Age (years) |

25- 35 |

10 |

17 |

|

|

35- 45 |

10 |

33 |

|

|

46-55 |

35 |

58 |

|

|

56 ≤ |

5 |

8 |

|

|

|||

|

Nationality |

Ugandan |

54 |

90 |

|

|

Non-Ugandan |

6 |

10 |

|

|

|||

|

Marital status |

Married |

40 |

67 |

|

|

Single |

10 |

17 |

|

|

Divorced |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Widows |

8 |

13 |

|

|

|||

|

Education |

None |

5 |

8 |

|

|

Primary |

15 |

25 |

|

|

Secondary |

25 |

42 |

|

|

Tertiary |

8 |

13 |

|

|

University |

7 |

12 |

Table 1: Socio-Demographic Characteristics.

As seen in the table above, the results depict that majority of the participants were male (58 %) while females constituted only 42 % of the total selected sample population. Most participants (58 %) were adults who ranged from 46 – 55 years followed by youths (33 %) from 35 – 45 and the least (8 %) were elderly above 56 years. The study further indicated that 90 % of the participants were Ugandans and only 10 % were non-Ugandans with identified nationalities of Kenyan and Tanzanian. It was also ascertained that the majority of the participants were married (67 %) and this to a greater extent signified a high degree of responsibility and the rest were single, divorced, and widowed with a corresponding percentage of; 17 %, 3 % & 13 % respectively. Low literacy level was noted amongst the respondents in our study, as 42 % were secondary school dropouts followed by primary (25 %) and the least those who had not gone to school at all (8 %). Only 13 % and 12 % representing a total of (25 %) had attained tertiary and university education, respectively. Therefore, to a certain extent, there is a likelihood of experiencing knowledge gaps in some of the responses generated most especially on those questionnaire items that required technical expertise.

3.1 Understanding the Concept of Cancer

|

Response |

Frequency |

% age |

P (value) |

|

Yes |

18 |

25 |

0.0006 |

|

No |

55 |

75 |

|

|

Total |

73 |

100 |

Table 2: Understanding the Concept of Cancer

Interestingly, we found out that some of the participants were able to give the meaning of cancer in their responses to structured questions. 25 % of the participants gave responses that were considered as correct meaning of cancer while 75 % did not understand the meaning of cancer at all. The number of participants who failed to define the term cancer was significantly higher (p =0.0006) than those who defined it. Therefore, natives in our study were not conversant with the term cancer.

3.3 Cancer Prevalence in Elgon Sub-region

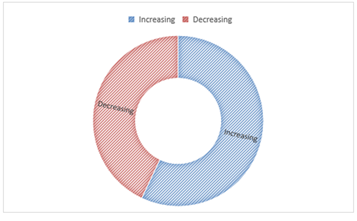

There were quite surprising outcomes on the prevalence of cancer in this area as 57 % of the respondents claimed increasing cases of cancer while 43 % disagreed in this regard. A test for comparison between the two proportions was insignificant (p=0.2864). Therefore, there is no change in the cancer prevalence in Sironko and Bulambuli districts. However, by all standards, there were some indicators of cancer manifestations across the eight villages of the present study but with a very minimal change in the number of patients annually.

3.4 Means of Cancer Transmission

The participants had varied perceptions of the different means of cancer transmission like unprotected cough with an infected person, sharing of bathrooms & toilets, sharing of sharp instruments, food & drinks, stepping barefooted in infected urine, and bacterial and viral infections. The highest number of participants (39 %) claimed that unprotected cough from cancer patients; followed by bacterial infections (36 %) and the least (12 %) suggested viral infections as the mode of transmission of cancer. The response of those who suggested that Cancer can be transmitted through unprotected cough visa-vi bacterial infections & sharing of the sharp instrument with an infected person was significantly higher (p=0.0057). The comparison between cough from unprotected persons with the rest of the cancer transmission modes was insignificant. A significantly higher (p=0.0001,) in the responses was generated among those who disagreed and agreed with the view that cancer can be transmitted through sexual intercourse, sharing of sharp instruments with infected persons, and viral infections. On the other hand, an insignificant (p=0.0691) was yielded for the participants who agreed on unprotected cough from cancer patients, stepping barefooted in infected human wastes, and sharing bathrooms & toilets with infected persons and those who agreed. To the best of our knowledge of cancer, some of the modes of cancer transmission documented are not anywhere documented as a means of cancer spread. Thus, the participant in the present study generally lacked basic knowledge as far as cancer treatment is concerned.

3.5 Signs and Symptoms of Cancer

|

Signs & Symptoms |

Response |

||||

|

Yes |

No |

Significance level |

|||

|

Freq. |

% age |

Freq. |

% age |

P (values) |

|

|

Unusual lamp/ swelling anywhere |

36 |

49 |

37 |

51 |

0.8653 |

|

Breathlessness (difficulty in breathing) |

31 |

42 |

42 |

58 |

0.2254 |

|

Very heavy night sweats |

18 |

25 |

55 |

75 |

0.0006 |

|

Croaky voice/ hoarseness |

28 |

47 |

32 |

62 |

0.2479 |

|

Persistent heartburn or indigestion |

33 |

45 |

40 |

55 |

0.0128 |

|

Mouth or tongue sores |

36 |

49 |

37 |

51 |

0.8653 |

|

Sore that slightly heal at any body parts |

55 |

75 |

18 |

25 |

0.0006 |

|

Change in bowel habits eg. Constipation |

26 |

36 |

47 |

64 |

0.0002 |

|

Loss of appetite |

40 |

55 |

33 |

45 |

0.4447 |

|

Unusual breast changes |

42 |

56 |

31 |

42 |

0.2864 |

|

Blood in fecal matter |

45 |

62 |

28 |

38 |

0.0007 |

|

Unexplained weight loss or gain |

27 |

38 |

45 |

62 |

0.0726 |

|

Skin pigmentation/ coloured spot on the skin |

31 |

42 |

42 |

58 |

0.2864 |

|

Unexplained chronic pain/ ache |

36 |

49 |

37 |

51 |

0.8653 |

Table 3: Signs and Symptoms of Cancer.

Generally, to a lesser extent, the participants in the present study had some basic knowledge of the signs and symptoms of at least all listed cancer types. Sore throats that slightly at the body parts, unusual breast changes, blood in fecal matter, and loss of appetite were the signs and symptoms cited amongst the participant with 75 %, 57 %, 55 % & 55 % respectively. On the other hand, very heavy night sweats, change in bowel habit like constipation, and unexplained weight loss or gain were the least documented signs and symptom cited among the participants on cancer patients. Unusual lamp/ swelling anywhere, mouth or tongue sores & unexplained chronic pain ache were averagely registered as signs and symptoms among cancer patients as far as participants in the present study are concerned. There was a significantly higher (p=0.0006) difference in responses of the participants on sores that slightly heals anywhere & blood in the fecal materials, (p=0.0007) as signs and symptoms of cancer. Therefore, these two were the highly perceived signs and symptoms of cancer by the natives in this area. On the other hand, there was a significant lower difference in the responses of the participants who agreed and disagreed on very night sweats (p=0.0006), persistent heartburn or indigestion (p=0.0128), and change in bowel habits (p=0.0002) as signs and symptoms of cancer and so were highly disregarded as signs & symptoms of cancer. Hence, these three were not considered signs& symptoms of cancer as per our present study. The remaining signs & symptoms were insignificant with respective p- values indicated in table 3 above so were less perceived as signs & symptoms of cancer.

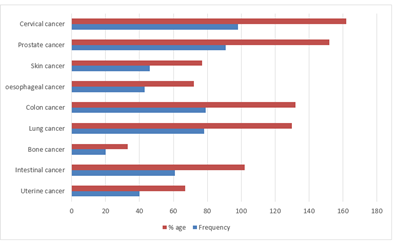

3.6 Types of Cancer in Elgon Sub-region

Cervical & p, p= 0.5725, p= 0.0001

The question regarding the various types of cancers among patients yielded varied and interesting responses were generated. A total of nine cancer types were listed by the participants in this study. The highest form of cancer identified in the present study was cervical cancer among females (98, 162 %) followed by prostate cancer among males (91, 152 %). Bone cancer registered the least (20, 33 %). Cervical cancer was significantly higher (0.0001) higher than all other cancers, except prostate cancer. There was an insignificant difference (p=0.5725) in the response between cervical and prostate cancers. However, since most participants in our study area were of low literacy class, it is highly doubtable if there were able to clearly distinguish between some of the much related cancers. For instance, to the best of our knowledge, the majority could not distinguish between uterine cancer from cervical cancers; intestinal from stomach and colon cancers, and so these related cancer types could have been interchangeably used. Therefore, the corresponding percentages cited for a particular type of cancer in our study are most likely to be either lower or higher than the actual.

3.7 Awareness of Cancer Risk Associated Behaviours

|

Response |

Frequency |

% age |

P (Value) |

|

Yes |

55 |

75 |

0.0006 |

|

No |

18 |

25 |

|

|

Total |

73 |

100 |

Table 4: Awareness of Cancer Risk Associated Behaviours.

An overwhelming number of the participants in the present study claimed to be in the know on cancer-associated risk behaviors as 75 % and only 25 % suggested they were not in know. A significantly higher (p=0.0006) value was yielded for the respondents who claimed to be in the know of cancer risks and associated factors and those who did not have an idea at all. Therefore, to a greater extent signified participants in the present had some ideas on the cancer risk-associated behaviors.

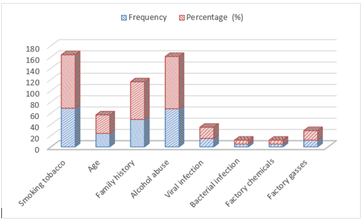

3.8 Cancer Risk Factors Identified

Various cancer risk-associated behaviors were identified. Smoking and alcohol abuse was the highest form of cancer risk behaviors (69, 95 % & 68, 93 %) respectively. Exposure to factory chemicals and gasses was cited with 2 % each in this regard. Other risk behaviors like family history, age factor and viral infections were documented with intermediate responses (49, 67 %, 24, 33 %, 15, 20 %, 15, 20 %, 5, 7%, 5, 7 % & 12, 17) respectively. Smoking yielded significantly higher (p = 0.0001) responses as compared to all other risk factors except alcohol abuse. An insignificant difference (p=0.6232) in the response between perceived smoking and alcohol abuse as cancer risk factors was generated. Hence, smoking, excessive and alcohol abuse were the most cancer-associated risk behaviors among natives in the present study.

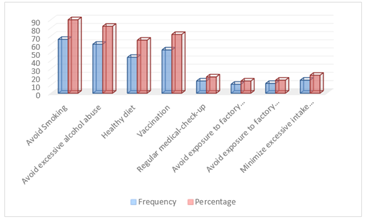

3.9 Cancer Prevention Interventions

Interestingly, a variety of responses on cancer prevention options were generated and to a larger extent, the participants exhibited a rich knowledge base in this regard. The highest percentage (54, 90 %) of participants believed that avoiding smoking could prevent cancer followed by avoiding excessive alcohol abuse (49, 82 %). Regular medical check-ups and minimization of exposure to factory gasses (12 %, 20 % & 9, 15 %) respectively were the least documented cancer prevention measures. Further still, healthy diet & vaccination yielded intermediate responses (39, 65 % & 43, 72 %) respectively. There was a significantly higher (p=0.0001, p=0.0273 & p=0.0003) difference in the responses of the respondents who agreed on avoiding smoking & excessive alcohol abuse, vaccination, and a healthy diet respectively than those who thought otherwise. Therefore, avoiding smoking, excessive alcohol abuse, a healthy diet, and vaccination were highly perceived as cancer prevention interventions by participants in this study. Regular medical check-ups and avoiding exposure to factory gasses were significantly lower (p=0.0001) for the participants who agreed to cancer prevention measures by residents in this area. Thus, regular medical check-ups and avoiding exposure to factory gasses as cancer prevention interventions were not perceived as cancer intervention strategies. However, to the best of our knowledge in disease control & prevention medical check-up serve a critical role.

3.10 Perception of Effectiveness of the Use of Modern Conventional and Traditional Medicine on Cancer Treatment

|

Item |

Response |

||||

|

Yes |

No |

P (Values) |

|||

|

Frequency |

% |

Frequency |

% |

||

|

Modern drug |

29 |

40 |

44 |

60 |

0.132 |

|

Traditional medicine |

40 |

55 |

33 |

45 |

0.4447 |

|

Traditional medicine + modern drugs (combination therapy) |

46 |

63 |

27 |

37 |

0.0537 |

Table 5: Perception of Effectiveness of the Use of Modern Conventional and Traditional Medicine on Cancer Treatment

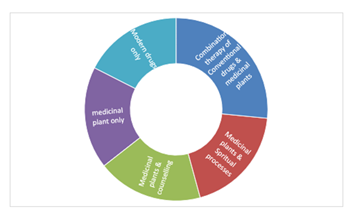

Interesting responses were generated to the questions. The responses on the effectiveness of either intervention used alone yielded responses that were below the average percentage. However, in either case, more natives (43 %) claimed that traditional medicine was more effective than modern cancer convention drugs alone (40 %). The majority of the participants (63 %) believed the combination therapy of both modern cancer conventional drugs and traditional medicine yielded promising results. The responses from participants who claimed that combination therapy was more effective than and use of medicinal plant or chemotherapy was insignificant (p<0.185 & p<0.121) respectively. Thus, no effective cancer treatment option was documented in the current study.

3.10 Cancer Treatment Options

Most of the participants (47 %) asserted that combination therapy of conventional drugs (chemotherapy) and medicinal plants was the most effective in cancer treatment compared to either treatment mode administered alone. The rest of the respondents claimed that cancer treatment options be the use of medicinal plants and spiritual processes, medicinal plants and counseling, medicinal plant only, and the use of modern cancer conventional drugs with corresponding percentages of 34 %, 33, 32 % & 31 % respectively. There was a significantly lower response among participants who regarded and disregarded the use of medicinal plants & spiritual processes (p=0.0198) medicinal plants & counseling (p=0.0164), medicinal plants only (p=0.0120), and modern drugs only (p=0.0120). An insignificant difference (p=0.158, p=0.172, p=0.187 & p=0.201) for claimed treatment options combination therapy, medicinal plants & spiritual processes, medicinal plants & counseling, medicinal plants and modern drug each used alone respectively. Therefore, natives in Sironko and Bulambuli districts lacked effective cancer drugs.

4. Discussion

The findings indicated that the majority of the participant (67 %) in this study were secondary and primary school dropouts and only 25 % constituted those who attained tertiary and university education combined (Table 1). This signified that; the majority of the participants were predominantly of a low literacy class. The low literacy class, combined with the remoteness of the participants in our study signified difficulties encountered in accessing the information on healthcare programs including cancer most especially through current broadcasting channels and social media. Therefore, information accessibility is only restricted to local FMs radio stations and word of mouth. Local radio FMs stations may also not be sustainable on daily basis due to difficulty in the accessibility and affordability of the dry cells to power their radios. Word of the mouth thus remains the only feasible and reliable form of information accessibility but with limitations like scope and frequency, The current study is also consistent with that conducted by [18] who reported that African migrants with high literacy class were 5 times more likely to give reliable information on cervical cancer screening than their counterparts of low literacy standards. This was linked to the ease in accessibility of healthcare information including cancer, increased level of interactions with healthcare expertise, social, press, and broadcasting media.

Responding to the questions on education status some of the responses were;

“I have never been on to school at all so, I don’t anything about little about cancer. “I only stopped in primary six class but I know something small about cancer.” I am senior three dropouts, I have never heard about cancer both at school and home so, I can tell you the little I know.” I went up to university so, I a well conversant with the causes and risks of cancer.” “I have some cancer knowledge based on personal experience and I have helped many cancer patients.”

The responses generated in this study can be supported by other variables in Health Belief Model as designed by Hochbaum (1958) and Rosenstock (1960) and cited in Health Behaviour & Health Education book (Chapter 3, page 50), documented by Barbara & Viswanath which states that,

“Diverse demographic, sociopsychological, and structural variables may influence perception and thus, indirectly health-related behaviors. For example, socio-demographic factors, particularly educational attainment have a direct and indirect influence on understanding certain diseases including cancers, their prevention interventions ……….” In the case of our study, high illiteracy rates imply that natives in this area have limited knowledge and perception of cancer and this complicates the whole process of diagnosis and early detection of the disease and so increased annual disease burden in this area may not be a surprise. On this basis, it can be deduced that, since the participants in the current study were of low literacy there are likely to have limited perception of the concept of cancer and stands a high chance of developing it in their lifetime if other factors are kept constant.

We found out that few respondents (25 %) could somewhat define cancer while the rest of the participants failed to define this concept (Table 2). The statistical test was significant (p =0.0006) for the response of participants who failed and those who defined had an idea for the correct definition. Therefore, the participants in the current study had a poorly perceived term cancer. This could be attributed to low literacy levels as the highest number of the participants were primary and secondary school dropouts and so, could not easily comprehend it. Similar observations were made by [19] who documented that local communities of the low literacy class and so had limited knowledge and perception of comprehending the term cancer, and so the importance associated with early detection and regular medical check-ups. Furthermore, studies by [20] opined that natives of low literacy were associated with rapid disease transmission among masses and such communities in comparison with the counterpart of a higher literacy class.

Some of the response correct responses generated and considered correct cancer definitions for cancer in their own words were;

“Cancer is a disease with non-healing wounds that can affect any part of the body.” Cancer is a disease that affects the lungs, liver, and kidney that affects other body parts that result in their swelling and non-healing wounds.”

“Cancer is a disease that is caused result from uncontrolled growth and swelling in any part of the body”.

On the other hand, some of the responses on cancer definition that were considered not correct in their own words were;

“Cancer is any disease that results into wound either healing or non-healing”; cancer is a disease that is usually sexually transmitted.” “cancer is a disease that only affects the lungs.”

The high failure to define cancer can be explained based on the Health Belief Model as designed by Hochbaum (1958) and Rosenstock (1960) and cited in Health Behaviour & Health Education book (Chapter 3, page 50) by Barbara & Viswanath which states that,

“Diverse demographic, sociopsychological, and structural variables may influence knowledge and perception of a given and thus, indirectly health-related behavior. For example, socio-demographic factors, particularly educational attainment……………….”

Based on the low literacy level of the participants in the current study, the failure of most participants to define the term cancer was not a surprise. In these cases, limited understanding of cancer, its causes, signs, and symptoms cannot be ruled out. We noted rising cases of cancer as 57 % of the respondents agreed there was an increasing trend of cancer incidences in this area while 43 % opposed it (Figure 4). A test for comparison of the proportionality for the increase and decrease yielded an insignificant difference (p=0.2864). Thus, there was minimal change in cases of cancer in the Sironko and Bulambuli districts. Our findings are in disagreement with the earlier report made by [21] where 50 million deaths were reported due to breast cancer with the subsequent rise to 1.7 million and 561334 deaths in 2012 & 2015 deaths respectively and a projection of 805116 (43 % ) cases by 2030 [22]. We also differed with the observations made by [23] who reported rising cases of colorectal cancer in their study in the United States and 1 in every 21 and 23 males and females were at the risk of suffering from this cancer [24,25]. This discrepancy could be explained based on the fact that the participants in the current study. This discrepancy could be attributable to limited knowledge of the importance of cancer screening coupled with its exorbitant costs, poor diagnostic facilities, and above all lack of a regional cancer registry makes the whole process of cancer detection difficult. So many residents in this area could be potentially suffering from cancers but due to these limitations, such cases have not been captured from the national registry.

“Twenty years back I had never heard or seen any cancer patient in our area until recently”. “Between 1990 to 2000 cancer patients were so rare in our village, unlike recent times.” “Cancer in my village is just a recent disease not more than 15 years back, since, the first case was diagnosed positive.”

The findings in our study are as well also supported by Health Belief Model as designed by Hochbaum (1958) and Rosenstock (1960) and cited in the book, towards an effective intervention extension of the Health Belief Model in the construct of “cues of action” & (Chapter 3, page 47) by Rita, Julita & Regan (2012) which states that;

“ ………….. a combination of threat and behaviors evaluation variable could reach a considerable level of intensity without resulting in an overt action unless an event occurs to trigger action in an individual, Thus, cue of actions are determined by external factors such mass media campaign, literacy level, and social influence, modern diagnostic facilities……………”

We observed that the participants in the present study had varying & interesting knowledge, perceptions, and attitude, and beliefs on cancer transmission but the majority believed that cancer is a contagious disease (Figure 5). As 39 % of the respondent claimed that cancer could be transmitted through unprotected coughing from an infected person, and the least (12 %) opined that it was through viral infection. A significantly higher (p=0.0001,) response among participants who agreed on sexual intercourse viva-vi sharing of sharp instruments & viral infections as cancer transmission modes. An insignificant difference (p=0.0691) was yielded for the participants who agreed on unprotected cough from cancer patients, stepping barefooted in infected human wastes, and sharing bathrooms & toilets with infected persons and those who agreed. To the best of our knowledge, some of the responses on cancer transmission are not applicable and have not been documented in any previous studies. This discrepancy could be attributed to low literacy levels and so limited access to healthcare information in regard to cancer transmission by most participants in the present study. Bacterial and viral infections were the only modes of cancer transmission documented in this study but have been supported by previous studies. But even then, cancer transmissible cases under normal circumstances, are so rare as per the existing literature. The results of our study to a small extent are in agreement with earlier studies conducted by [26,27] where it was opined that some cancers could be transmitted through specific viral and bacterial infection from infected individuals; from mother to fetus and also from twin to co-twin via vascular anastomosed within the placenta [27]. Also study explored [28] in the study titled “is cancer contagious: reported mixed responses just like the current as the majority of the respondents had a belief that cervical cancer was caused by Human papillomavirus (HPV) and was highly contagious and this resulted into a high level of stigmatization and fatality associated with this disease This was attribute to limited healthcare education and awareness among girls in those schools where their study was conducted. On the contrary, Sergey (2013) reported that human cancer unlike other animals is not transmissible at all. This is because their study was based on a laboratory-based model and specific types of cancer and drew general conclusions which may sometime be misleading [29].

Some of the attitudes of participants about cancer in their own words were;

“Cancer is a disease of the rich who always affords of meat, fatty foods, fried and processed foods & drinks, and avoiding such kind of diet can minimize cancer disease.” “Current government program of vaccination against HPV has reduced the occurrence of cervical cancer among girls.” “Knowing your cancer status through continuous medical check-ups helps in preventing cancer occurrence.”

The findings in the present are in line with three constructs of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity & perceived motivation in the Health Belief Model as designed by Hochbaum (1958) as cited [30,31] and cited in the Health Behaviour & Health Education book (Chapter 3, page 47) which states that,

“Perceived susceptibility explains that people will be more motivated to behave in healthy ways if they believe they are vulnerable to a particular negative health outcome [31]. The personal perception of risk or vulnerability is important in promoting the adoption of healthier behaviors [30].” “Perceived Severity: “…… refers to how serious an individual believes the consequences of developing the health condition will be. It deals with an individual’s subjective belief in the extent of harm that can be caused by acquiring the disease or unhealthy state, as a result of a particular behavior. An individual is more likely to take any action to prevent gaining weight if s/he believes that the possible negative physiological, psychological and social effects resulting from becoming obese pose serious consequences.”

Thus on this basis, once the residents in this area are equipped with basic on the vulnerable activities that could lead to cancer development and severity of cancers in terms of pain and treatment cost of disease. Then they are likely to change their behaviors to reduce the disease burden and overcome its associated severity. Our study, we also found out that the respondents in this study were to some extent were in familiar with basic knowledge of the signs and symptoms of cancer (Table 3). 75 %, 57 %, 55 % & 55 % which corresponded to sore throats that slightly. There was a significant higher (p=0.0006) difference in responses of the participants on sores that slightly heals at any part of the body and blood in the fecal materials, (p=0.0007) as signs and symptoms of cancer. Therefore, these two were the most perceived signs and symptoms of cancer patients by the natives in this area. On the other hand, there was a significantly lower difference in the responses of the participants who agreed on very night sweats (p=0.0006), persistent heartburn or indigestion (p=0.0128), and change in bowel habits (p=0.0002) as signs and symptoms of cancer. Therefore, every night sweats, persistent heartburn or indigestion, and change in bowel were disregarded by natives in this area as signs and symptoms of cancer. Similar observations were made by Bianca et al (2020) in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania who revealed some of the common signs & symptoms of cancer like; blood in fecal materials & sore throat [32,33]. But disagreed on very heavy night sweats and appetite as common signs and symptoms of cancer. This could be attributed to different types of cancers, for example, their study was carried out in areas where GIT cancers were more pronounced unlike the study under question. Mohamad et al also highlighted other symptoms and signs like hoarseness, skin color changes, and unexplained weight loss were cited as some of the signs & symptoms of cancer similar to this study though less frequently cited [34].

Some of the responses generated were;“ A person with cancer has a sore which rarely heals at the mouth.” “heartburn or indigestion signs (constipation) are signs of stomach cancer, voice hoarseness and skin spots are the sign of cancers and all these were perceived as undesirable conditions for good health.

This can be supported by the perceived severity of a construct of the Health Believe Model designed by Hochbaum (1958) as cited in the book of Health Behaviours and Health Education (page 5) Rita, Julita & Regan (2012) which states that;

“Perceived severity …………………………….. Although the perception of the seriousness of any health condition may be based on medical knowledge, it may also come from one’s belief about the difficulties a disease would create or the effects it would have on his or her life.....

Once the residents in this area are enriched with basic knowledge of signs & symptoms then they could change terms to minimize disease incidence among the masses in this area.

A total of nine (9) different types of cancers were documented in our study. Cervical & prostate cancers were the most pronounced form of cancer cited (98, 162 % & 91, 152 %) in females and males respectively and the least form of cancer was bone cancer (20, 33 %) (Figure 6). Cervical cancer was significantly higher (0.0001) higher than all other cancers, except prostate cancer. There was an insignificant difference (p=0.5725) in the response between cervical and prostate cancers. Our study to a greater extent is in agreement with the study revealed by Ferlay et al and GLOBOCAN where prostate and breast cancer were the most documented forms of cancer in females and males respectively [3,35]. On the contrary, however, unlike our study, other types like skin, gastric and oesophageal cancers were reported as leading cancers in Iran and other Middle East countries but either less or not documented at all in the present study [36,37]. Our findings are also consistence with a report made by the World Health Organization (WHO) where prostate cancer incidences were pinpointed at rates of 2,634 individuals per annum and in the same report, Uganda was ranked as the 8th globally regarding this type of cancer [38]. Further still, the results in the present study also concurred with those revealed by Phiona et al (2021) where a rise in different types of cancers was documented in Kampala, particularly in Kyadondo county, amounting to 33. 3357 cases for the duration of 25 years (1991-2015). Prostate cancer alone was documented at rate of 55.1 per 100,000 individuals. Similarly, Marc et al (2020) cited that cervical cancer as the most prevalent cancer across various continents and sub-continent in the world. For instance, their study found out that Eastern African sub-continent where Uganda lie was ranked 1st with 218.4 cases per 100, 000 cases representing 26.5 % of the total cancer followed by Middle Africa 84.6 per 100, 000 which represented 23.6 % of the total cancer burden. On the contrary, Phiona et al pointed out Kaposi sarcoma, oesophageal and breast cancer as the most predominant cancer which were either less frequently or not documented at all in current study [39]. This discrepancy could be attributed in the low literacy level and limited exposure and access to information by the participants in the present study. For example, whereas their study was carried in the capital city of Uganda, where most participants are believed to be of the highest literacy class in the country and could easily access information and so, were knowledgeable enough to clearly distinguish between the various types may not be the case in present remote-based study. Responding to the question about the awareness of cancer risk behaviors, 75 % agreed to be in the know in this regard while 25 % did not know (Table 4). However, given the low literacy class and exposure of participants in our study combined with limited access to information, even some of them who claimed to know of cancer-associated risk factors still are doubtable of the level of their comprehension. There was a very significant difference (p=0.0006) in the response between those who claimed to know about cancer risks associated risk and those who did not have an idea at all. Therefore, it can be summed up that participants in the present were knowledgeable of cancer risk-associated behaviors. Observations made by Oresto et al opined that participants in Tanzania were also showed the residents in the Kilimanjaro region were aware of various cancer risk factors, for example, 90 %, 67 %,54 % & 16 % suggested tobacco, strong spirits, alcohol type & home-brewed alcohol were type as the major cause for lung, oesophageal, liver, and gastric cancers which much are much similar to those in the present study [32]. Similarly, [13] documented that 95 % of the respondent in Bugiri and Mayuge in Eastern Uganda were aware of cancer risk behaviors specifically cervical cancer [13]. Our study further agrees with the finding unveiled by Mwaka et al on the status of awareness of cancer risk factors in Northern Uganda particularly in the Gulu district where 99.1 % of the participants agreed to have heard about cervical cancer, it's screening, and their participants largely shared similar demographic characteristics with the study under question [40]. Our study also cited various cancer-associated cancer-associated risk behaviors. The most frequently cited factor was smoking (57, 30 %) followed by alcohol abuse (56, 29 %), and exposure to factory gasses and chemicals was the least (2 % each). Other intermediately documented cancer risk-associated factors were; family history (21 %), age (10 %), and viral infections (Figure 7). Smoking & excessive alcohol abuse were significantly higher (p=0.0001) than other risk factors age and family history (p=0.0132). Hence, these were the most perceived cancer-associated risk factors among natives in the current study. Further, still, Lawson et al revealed that secondhand smoke (SHS) contains over 3,000 chemicals and of which over 50 were well known to have a carcinogenic effect on human health while 200 were documented as poisonous [41]. Therefore they concluded that continuous inhaling these chemicals either actively or passively from an individual could subsequently cause a devastating impact on such an individual [42,43]. This clearly explains why lung cancer is the leading form of cancer cited as the most common among patients globally. On the other hand, a significantly lower (p=0.0001) was yielded between participants who regarded factory chemicals & gasses and viral and bacterial infections as cancer risk factors and those who agreed. Thus, factory gasses & chemicals, and bacterial and viral infections were not cancer risks in this area. Unlike the current study by Mwaka et al where they pointed out cancer risk factors in the Gulu district such as multiple sexual partners, human papillomavirus, and early sexual activity which were recognized by 88 %, 82 %, and 78 % [40]. This is because their study was specifically carried out on cervical cancer where sexual transmission may under some circumstances be a mode of transmission, unlike this more general study.

Some of the responses generated on cancer risk behaviors were;

“ I fear smoking because I fear suffering from cancer.” I fell spathe with my friend in this area who abuses alcohol because you never know in future, they may develop some complications like cancer”.“I fear using condoms because it causes cervical cancer to my wife.” “Since I was born, I have never eaten bottled milk or processed food because they cause several diseases older age.” Normally cancer develops with age, so I fear to live up to 90 years” “turned down my factory job because I feared that those chemicals and gasses would lead to cancer in the future.”

Therefore, all the above responses imply that when local communities in our study area to a small extent were in the knowledge of cancer risk behaviors. So on basis, if some other factors are kept constant they are likely to reduce the chances of developing cancers in their lifetime. The qualitative responses from the participants in this study are supported by three constructs of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity & perceived barriers of the Health Belief Model that as designed by Hochbaum (1958) and Rosenstock (1960) and cited in the book of Health Belief Model by Edward, Elaine, and Kristina (2003), page 212.

The construct of perceived severity states that;

Perceived susceptibility “ ……………In order words, it is the subjective belief a person has regarding the likelihood of acquiring a disease or harmful state as a result of indulging in a particular behavior. Perceived susceptibility explains that people will be more motivated to behave in healthy ways if they believe they are vulnerable to a particular negative health outcome.”

Perceived susceptibility is predictive of several health-promotion behaviors including smoking cessation, breast self-examination, healthy dental behaviors, and healthy diet and exercise……………….” “However, in general, it has been found that people often underestimate their susceptibility to disease ………………………………………”

Perceived severity “……………… An individual is more likely to take any action to prevent gaining weight if s/he believes that the possible negative physiological, psychological, and social effects resulting from becoming obese pose serious consequences (e.g., death, physical impairment leading to other health conditions, financial burden, pain and discomfort, and difficulties with family and social relationships)” …………………

Perceived barrier “………… an individual may not perform a behavior despite his/her belief about the effectiveness (benefit) of taking the action in reducing the threat if the barrier outweighs the benefit …………………”.

Interesting and varied responses were generated in response to the question of cancer intervention or prevention options (Figure 8). The result indicated that the majority of the respondents (90 %) supported the idea of avoiding smoking as the best cancer prevention measure while the least (15 %) suggest minimization of exposure to factory chemicals and gasses (Figure 8). Avoiding smoking, excessive alcohol abuse (p=0.0001), vaccination (p= p=0.0273), and a healthy diet (p=0.0003) were significantly agreed on Viv-v those who disagreed. Therefore, avoiding smoking, excessive alcohol abuse, a healthy diet, and vaccination were most perceived as cancer prevention interventions by the participant in this study. The findings of this study are also in line with [44] where several prevention measures were outlined; such as avoiding smoking, early detection, dietary supplementation, avoiding alcohol, and vaccinations. Their study, however, revealed other prevention options like chemoprevention which did not surface anywhere in our study. Also, a study revealed by [45] that regular screening for cervical cancer and reduction of screening costs could serve as a perfect cancer prevention intervention. However, other prevention measures like educating and increasing awareness on social media for promotion of prevention strategies, and improving access to cancer health facilities were part of their findings, unlike the present study. This discrepancy could be attributed to the difference in the study population and the developmental level of the study area. For example, whereas their study was carried out in the United States which is a highly developed country and so all the forth-mentioned services are easily available and affordable was not the case in our study. On the other hand, regular medical check-ups and avoiding exposure to factory gasses yielded significantly lower (p=0.0001) perceptions as cancer prevention measures. Thus, the natives in this area did not take regular medical check-ups and avoided exposure to factory gasses as cancer serious cancer prevention interventions. This is in line with an earlier report made by Rachael et al (2021) who opined that 97.8 % of the participant suggested that adoption of a healthy diet (nutrition), regular screening, and physical activity were some of the major cornerstones cited in cancer prevention interventions [46] but still the quoted percentage was higher than the current study. The lower perception of avoiding factory gasses prevention option in this area is because the area is very remote and so no factory has ever viewed this study and worse of it all even electricity is less common in most parts of these districts.

Some of the responses, from participants, were;

“Some patients once diagnosed with opting to get medication from traditional medicine practitioners”. “We have no trust in traditional medicine and so at whatever cost, once diagnosed positive for cancer they opt for modern and conventional cancer drugs”. “In this area, once one gets cancer s/he has been admitted to hospital then thereafter he subjected to plant medicine.” “ I don’t truth plant medicine, so once diagnosed so I advise whoever contracts it to get hospital treatment”

This can be supported by three constructs of perceived barrier, perceived severity & perceived self-efficacy of the Health Believe Model designed by Hochbaum (1958) as cited in the book of Health Behaviours and Health Education (page 5) Rita, Julita & Regan (2012) which states that;

Perceived barrier “……. The barrier often relates to the characteristics of the health promotion measure. It may be expensive, painful, inconvenient, and unpleasant. These characteristics may lead one away from adopting the behavior. To adopt the new healthy behavior, people have to believe that the benefits by far outweigh the consequences of continuing the old behavior………………………………

Perceived benefit “……………………..The individual must perceive that the target behavior will provide strong positive benefits. Specifically, the target behavior must tend to prevent the negative health outcome.

Self-efficacy “………………………The individual must perceive that the target behavior will provide strong positive benefits. Specifically, the target behavior must tend to prevent the negative health outcome.”……………………

Our study also indicated that 63 % of participants agreed that combination therapy for both modern conventional drugs (chemotherapy) and traditional medicine was more effective in cancer treatment while 55 % believed traditional medicine alone could treat cancer and only 40 % trusted the use of only modern cancer conventional drug (Table 5). There was an insignificant difference in the perception of the effectiveness of the use of modern, traditional & combination therapy (p=0.1320), use of modern drugs alone (p=0.4447), and medicinal plant ( p=0.0537). Therefore, was no effective treatment option for cancer treatment so far available by natives in Sironko & Bulambuli districts. Unlike observations made by Cristina et al demonstrated that the addition of Aidi plus chemotherapy (combination therapy) significantly exhibited anticancer activity, tumor inhibition, and immunological functions [47]. Other previous studies further disagree with the present study where medicinal plants have been documented to be more effective in cancer treatment options. For example, curcumin was found to exhibit antitumor activities and was mediated through the inhibition of multiple pathways signaling pathways involved in the regulation of proliferation, apoptosis, survival, angiogenesis, and metastasis [48]. Our study also differed from Wing-Hin et al (2021) where it was revealed that when curcumin or paclitaxel was used alone, caused increased apoptosis and reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and so increased the release of cytochrome C [49]. Curcumin was more effective in this regard as compared to paclitaxel. Thus, their study somewhat supported the claims that medicinal plants were more effective than chemotherapeutic drugs [49]. Therefore, combination therapies under all standards proved to be more effective in cancer management as compared to the use of either medicinal plants or chemotherapy alone. This difference in the current study could be explained based on the type of study. For example, whereas, the previous studies were purely experimental design based on laboratory and clinical trials and so less biased unlike the current whose findings was based on people knowledge, perceptions and attitude. This question generated interesting views, the majority of the participants (47 %) claimed that cancer could be treated by combination therapy of conventional drugs and medicinal plants. This was followed by 34 % who asserted that medicinal plants and spiritual processes, use of cancer conventional drugs yielded the least (31 %), and the rest; medicinal plants and counseling medicinal plants alone had an intermediate response (Figure 8). There was a significant lower (p=0.0198), in the responses among those who regarded the use of medicinal plants & spiritual processes as medicinal plants & counseling (p=0.0164), medicinal plants & modern drugs only (p=0.0120). Therefore, there are no effective cancer treatment options for natives in Sironko and Bulambuli districts as effective cancer treatment options. An insignificant difference (p=0.656) between the participants who disagreed with the use of combination therapy and those who thought otherwise. Unlike the current study, the study by Katherine indicated that chemotherapy and surgery were the most effective cancer treatment modes and no medicinal plant with healing benefit was reported in their study. Suhail et al (2021) revealed that Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-kB), a specific chemotherapeutic drug could be used to treat various cancers including but not limited to; breast, lung, liver, pancreatic, prostate, and multiple types of lymphoma. Unlike, the current findings documented by [50] revealed various cancer treatment options such as nanoparticle & thermal therapy, photothermal therapy (PTT), magnetic hyperthermia treatment (MHT), ultrasounds (US) and radiofrequency (RF)- induced thermal therapy, photodynamic therapy (PDT), so no dynamic therapy (SDT), chemotherapies in combination with thermal therapy Combination of PTT and SDT. Larisa also highlighted that chemotherapy was an effective remedy for breast remedies for cancer [51]. However, other remedies such as endocrine therapy and targeted therapy were also documented in their study and did not surface anywhere in our current study. This could be attributed to the difference in research conducted. For example, where their study was experimental based on several clinical trials, our study was a mainly qualitative study that greatly assessed people's knowledge, beliefs, and opinions on cancer.

Some of the responses, in the participant's own words, were;

“cancer patients opt for medicinal plants with spiritual processes for fast healing.” “Medicinal plants combined with counseling serve better in cancer treatment.”

“it is better to use combination therapy of cancer conventional drugs and medicinal plants as very effective in cancer treatment”.

“cancer patients have no trust in the healing power of medicinal plants and so only use cancer conventional drugs. “medicinal plants alone are more effective in cancer treatment”.

Hence, these responses alone, unveiled that natives in the Elgon sub-region have a wide range of cancer treatment options.

The findings in the current study are in agreement with the Health Belief Model (HBM) as designed by Hochbaum (1958) and Rosenstock (1960) and cited in Health Behaviour & Health Education book (Chapter 3, page 47) which states that,

Perceived barrier: “……………………. with a perceived barrier, an individual may not perform a behavior despite his/her belief about the effectiveness (benefit) of taking the action in reducing the threat if the barrier outweighs the benefit. The barrier often relates to the characteristics of the health promotion measure. It may be expensive, painful, inconvenient, and unpleasant. These characteristics may lead one away from adopting the behavior. To adopt the new healthy behavior, people have to believe that the benefits by far outweigh the consequences of continuing the old”………………………..

Perceived benefit: “……………………..specifically, the target behavior must tend to prevent the negative health outcome. For instance, individuals who are not convinced that there is a relationship between eating and gaining weight are unlikely to adopt a healthier eating behavior for the mere purpose of reducing their chances of getting obese” ……………………

5. Conclusions & Recommendations

The majority of the study participants were males (58%), aged between 46 – 55 years (58%), Ugandans (90%), and married (67%). Most of them had inadequate knowledge about cancer (p<0.05) and highlighted sores that slightly heal at any body parts as well as blood in feces as putative predictors of cancer infection (p<0.005). A total of nine cancer types were documented and cervical was the most prevalent (p<0.0001). Smoking was the most pronounced cancer-associated risk factor (p<0.0001) and avoiding smoking was perceived as the major prevention option (p<0.0001). No effective cancer treatment options were cited in this area (p<0.172). Since the majority of the participant in our study were of low literacy class and had limited exposure to information sources like broadcasting, social and press media, there need to enhance cancer healthcare programs through word of the mouth and radio talk shows. It is paramount to carry out an ethnobotanical investigation to document plants with claimed anticancer activity.

Ethical Approval and Consent

Approval for this study was provided by the Islamic University in Uganda, Research Review Committee. Permission to access the communities was obtained from Sironko and Bulambuli districts Local leaders including LC1 Chairpersons of the respective villages. We explained the purpose of the study to the respondents, provided oral informed consent, and signed applied thumbprints to register the participants in our study. In addition, verbal permissions were obtained from participants to allow the auto-recording of discussions and finally, a uniform transport refund was provided for all the participants.

Availability of data and materials

Data sets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicting Interests

We the authors of this article declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Funding

This research was fully funded under the research and innovation grant awarded to Islamic University in Uganda (IUIU) by the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB).

Authors’ Contribution

“Ali Kudamba (AK) and Abdul Walusansa, conceived the research idea, participated in the data collection & analysis and in writing the primary draft of the manuscript” “Nsubuga Hakim (NH) & Hussein Mukasa Kafero (HMK) participated in data collection, advised on data entry plan and were major contributors in writing this manuscript.” Jamilu E (JES) Ssenku and Shaban A Okurut (ASO) were the senior advisors and supervisors in the study. They were also major contributors to the writing of the manuscript and performed final editing of the manuscript”. All authors read and approved the final manuscript."

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the administration of the Islamic University in Uganda (IUIU) in partnership with the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) for their financial and moral support towards the success of this work. We also acknowledge and express our gratitude to the Dean Faculty of Health Science and Dean Faculty of Science of the Islamic University in Uganda for their administrative, physical and moral support rendered to us during the whole process of the article write-up.

References

- Harith A, Shamsul AS. Perception of Cancer Risk and Its Associated Risk Factors among Young Iraqis living in Baghdad. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 20 (2019): 2339-2343.

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018 Eur J Cancer 103 (2019): 356-387.

- Uganda-global cancer observatory,” WHO, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. (2019).

- Wabinga HR, Nambooze S, Amulen PM, et al. Trends in the Incidence of Cancer in Kampala, Uganda 1991-2010. 2014 Int J Cancer 135 (2014): 432-439.

- Macrae FA. Colorectal cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, and protective factors. Uptodate com [a?urirano 9. lipnja 2017. 2016. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 7 (2016): 105-114.

- Mahmoud M, Yaser A, Abdusalam A, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of primary health care physicians toward colorectal cancer screening 23 (2017): 330-336.

- Werk RS, Hill JC, Graber JA. Impact of knowledge, Self-efficacy, and perceived importance on steps taken toward cancer prevention among college men and women. . J Cancer Educ 32 (2017): 148-154.

- Werk RS, Hill JC, Graber JA. Impact of knowledge, Self-efficacy, and perceived importance on steps taken toward cancer prevention among college men and women. J Cancer Educ 32 (2017): 148-154.

- Brinton LA, Brown SL, Colton T, et al. Characteristics of a population of women with breasts implants compared with women seeking other types of plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 105 (2000): 919-927.

- Statistics: The National Population and Housing Census, 2014- Main Report, Kampala. (2016).

- LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J. Nursing Research: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence Based Practice. Mosby, St Louis. (2006).

- Richard C, John D. The Age Structural Maturity Thesis: The Impact of the Youth Bulge on the Advent and Stability of Liberal Democracy. (2012).

- Trasias M, Rawlance N, Angele M, Abdullah AH, David M. Women’s knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer prevention: a cross sectional study in Eastern Uganda. BMC Women's Health 17 (2017): 9.

- Mandy MA, Amanda IR, Xiaozhou Z, et al. Current Mixed Methods Practices in Qualitative Research: A Content Analysis of Leading Journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. (2015).

- John WC, William EH, P.C VL, et al. Qualitative Research Designs: Selection and Implementation. (2007).

- Glanz, Rimer KB, Viswanath K. et al. 4th ed. San Francisco: .Jossey-Bass, Awiley imprint; (2008).

- Rita O, Julita V, Regan M. Towards an Effective Health Interventions Design: An Extension of the Health Belief Model 34 (2012).

- Joycelyn C, Joseph J, Gallo J, et al. The Role of Sources and Types of Health Information in Shaping Health Literacy in Cervical Cancer Screening Among African Immigrant Women: A Mixed-Methods Study. Health Literacy Research and Practice 5 (2012): e96-e108.

- Julie AW, Joseph GG, Sara AQ, et al. Men’s Knowledge and Beliefs about Prostate Cancer: Education, Race, and Screening Status. Ethn Dis 19 (2009): 199-203.

- Cecilia MS, Conrath D, Leonard G, et al. Improving comprehension for cancer patients with low literacy skills: Strategies for clinicians. (1998).

- Fatima C, Danielle S, Shirley M, et al. . Global analysis of advanced/metastatic breast cancer: Decade report (2005e2015) (2015).

- Elsevier (2018).

- Jeffrey D, Benjamin G, Sanjib C, et al. Colorectal cancer—global burden, trends, and geographical variations. J Surg Oncol 9999 (2017): 1-12.

- Jeffrey D, Benjamin G, Sanjib C, et al. Colorectal cancer—global burden, trends, and geographical variations. J Surg Oncol 9999 (2017): 1-12.

- Society AC. Lifetime risk of developing or dying from cancer. In. 2016. American Cancer Society (2016).

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. Cancer J Clin 66 (2016): 7-30.

- WHO Guidelines for Safe Surgery 2009: Safe Surgery Saves Lives. Geneva (2009).

- Cooper R, Diana B, Kirsten M, et al. Is cancer contagious? Australian adolescent girls and their parents: Making the most of limited information about HPV and HPV vaccination. Vaccine 28 (2010): 3398-3408.

- Sergey AD, Friedemann H. Marine Compounds and Cancer: 2017 Updates. Mar Drugs 16 (2018): 41.

- Abraham C, Sheeran P. The Health Belief Model: In Conner MaN, P Eds, Predicting Health Behaviour: ls, editor. Maidenhead: Open University Press; (2005).

- Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behaviour. Health Education Monographs 2(1974).

- Oresto MM, Valerie M, Bariki M, et al. Awareness of Cancer Risk Factors and Its Signs and Symptoms in Northern Tanzania: a Cross-Sectional Survey in the General Population and in People Living with HIV Journal of Cancer Education 35 (2020): 696-704.

- Bianca O, Rodolfo H, Massimo L, et al. Characterization of the urinary microbiota in bladder cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology 38 (2020).

- Mohamad MS,N B K C, Serena F, Geralda A, et al. Awareness and help-seeking for early signs and symptoms of lung cancer: A qualitative study with high-risk individuals. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 50 (2021).

- Ferlay J, Soejomataram FBJF, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer Incidences & Mortality Worldwide: Source, Methods and Major Pattern in GLOBOCAN in 2012. int J Cancer 136 (2015): 394.

- Razi S, Rafiemanesh H, Ghoncheh M, et al. Changing trends of types of skin cancer in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16 (2015).

- Babazadeh T, Nadrian H, Banayejeddi M. Determinants of Skin Cancer Preventive Behaviors Among Rural Farmers in Iran: an Application of Protection Motivation Theory. J Cancer Educ 32(2017): 604-612.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. Cancer journal for clinicians 67(2017): 7-30.

- Phiona B, Henry W, Sarah N, et al. Trends in the incidence of cancer in Kampala, Uganda, 1991 to 2015. Int J Cancer 148 (2021): 2129-2138.

- Mwaka AD, Christopher GO, Edward W, et al. Awareness of cervical cancer risk factors and symptoms: Cross-sectional community survey in post-conflict northern Uganda. International Journal of Public Participation in Healthcare and Healthy Policy 19 (2015).

- Lawson E, Jie S, Xin Q, et al. Second-Hand Smoke As a Predictor of Smoking Cessation Among Lung Cancer Survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 32 (2020).

- Daichi M, Masamitsu K, Denisa N, et al. Exposure to Cigarette Smoke Enhances Pneumococcal Transmission Among Littermates in an Infant Mouse Model. Frontier in Cellular and Infection Microbiology (2021).

- Hovanec J, Siemiatycki J, Conway DI, et al. . Lung cancer and socioeconomic status in a pooled analysis of case-control studies. PLoS ONE 13 (2018): e0192999.

- Michael O, Peter B, Martin L. Cancer prevention. The Lancet (1997).

- Sumit KS, Maggie JC, Milan B, et al. An Online Survey and Focus Groups for Promoting Cancer Prevention Measures. Journal of Cancer Education 23 (2021).

- Rachael P, Wendy LF, Benjamin JS, et al. Prospective Statewide Study of Universal Screening for Hereditary Colorectal Cancer: The Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative. Clinical Oncology Journal (2021).

- Cristina AD, Lasmina M, Codruta S, et al. Plant-Derived Anticancer Compounds as New Perspectives in Drug Discovery and Alternative Therapy. molecules26041109 26 (2021).

- Zhang XM, Liu X, Pan Q. Effects of chemotherapy and Aidi injection on nude mice breast carcinoma implanted of Her-2/neu over-expression,” Journal of Emergency of Traditional Chinese Medicine 18 (1654).

- Wing-Hin L, Ching-Yee L, Daniela T, et al. Development and Evaluation of Paclitaxel and Curcumin Dry Powder for Inhalation Lung Cancer Treatment. pharmaceutics13010009 13 (2021): 9.

- Tareq A, Shiva R, Nayer S, et al. MRI-traceable theranostic nanoparticles for targeted cancer treatment. Theranostics 11 (2021): 591.

- Larissa AK, Mark RS, Lisa AC, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, Endocrine Therapy, and Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer: ASCO Guideline Journal of Clinical Oncology 39 (2020).

Article Views: 920

Journal Statistics

Discover More: Recent Articles

Grant Support Articles

© 2016-2024, Copyrights Fortune Journals. All Rights Reserved!