The Relevance of Cultural, Fatalistic and Psychosocial Factors in Breast Cancer Screening Behavior in Middle Age and Older Women

Article Information

Luciano Cermignani, Martin E. Rabassa, María Virginia Croce*

Center for Basic and Applied Immunological Research (CINIBA), Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of La Plata, La Plata, Argentina

*Corresponding author: Maria Virginia Croce. Center for Basic and Applied Immunological Research (CINIBA), Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of La Plata, Calle 60 and 120, 1900 La Plata, Argentina.

Received: 31 January 2023; Accepted: 13 February 2023; Published: 13 March 2023

Citation: Luciano Cermignani, Martin E. Rabassa, María Virginia Croce. The relevance of cultural, fatalistic and psychosocial factors in breast cancer screening behavior in middle age and older women. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences 6 (2023): 75-87.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The aim of this study was to analyze cultural and social factors in advantaged and disadvantaged women in relation to mammographic screening. A cross-sectional study was performed; 850 women aged 45-79 years were interviewed; based on socioeconomic aspects, women were grouped in low economic power (Low group, LG) (379 women) and middle economic power (MG) (471). A questionnaire previously validated was employed and information about cultural, fatalistic, and psychosocial factors as well as breast cancer and mammographic screening was assessed. An extensive statistical analysis was performed including three regression models and a principal component analysis. 98% MG and 49.7% LG had a high level of education. Women who stated having a high level of education, regularly visit a doctor and being communicatively open showed the most positive mammographic screening behaviors. In general, analysis of fatalistic affirmatives in relation to mammogram variables did not show a significant difference in relation to total MG and LG while psychosocial variables showed a very low significant relationship with mammographic screening. Regression analysis showed similar results. This study highlights that communication as well as family and social support constitute important factors which impact on mammographic screening, while fatalism, although present, should not constitute a crucial aspect.

Keywords

mammographic screening, psycho-socio-cultural factors, fatalistic factors, middle age and older women

mammographic screening articles, psycho-socio-cultural factors articles, fatalistic factors articles, middle age articles, older women articles

Article Details

1. Introduction

A number of studies and reviews have shown that mammography and early detection reduce breast cancer mortality [1,2]. Despite the efficacy of mammography and the widespread promotion to attend screening programs, a significant number of eligible women still do not attend for regular breast cancer screening. It has been documented that factors such as increasing age, low income and education, single marital status, the absence of insurance and lack of physician recommendation were predictive of poorer mammography utilization in Argentina [3,4]. Argentina presents social and economic disparities; women constitute a heterogeneous group having differences in education and economic power [5].

In a recent study developed in La Plata, the capital city of Buenos Aires Province (Argentina), we found that adherence to mammographic screening to be associated to regular Physician visits and the possibility to perform mammograms which depends on the Health System [4]. Nevertheless, the high incidence of breast cancer in Argentina [6], also highlights the importance to better understand the determinants involved in health behavior. It appears that social, cultural, including fatalism, as well as psychological factors have relevance on mammographic screening [7,8]. The goal of this research was to analyze these aspects in advantaged and disadvantaged women in order to clarify their influence on breast cancer screening behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed in La Plata, the capital city of Buenos Aires Province (Argentina). After obtaining written informed consent, women were personally interviewed employing a structured previously validated questionnaire [9] (questions are available in Table 1). An existing measure used in a previous research [4] was assessed with a total of 850 women interviewed who indicated occupation, place of residence, marital status, and neighborhood; based on these categories, two groups were formed: low economic power (Low group, LG) (379 women) and middle economic power (MG) (471); age range was from 45 to 79 years old.

Socially shared values, beliefs, expectations, motivations and emotions relevant to behavior in relation to mammographic screening and breast cancer worry were provided by respondents. We hypothesized that breast cancer screening behavior is influenced by these factors, which were here divided in three categories: cultural, fatalistic and psychosocial, considering the socioeconomic group. In each section, first, we presented affirmative answers according to the socioeconomic group (MG and LG); next, affirmative responses were analyzed in relation to some health and social factors: Physician visits, educational level, and Health System, and after, to mammographic screening variables; finally, regression models were performed.

2.2 Data analysis

Chi-square test of independence was employed to examine the relationship between nominal variables. For categorical variables, Kendall’s tau correlation was performed to test for independence. Three ordinal regression models were employed to test dependence of the ordinal variables “Age at first mammogram”, “Frequency of mammograms” and “Time since last mammogram”. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to summarize the variables corresponding to cultural, fatalistic, and psychosocial factors; three principal factors for each group were extracted from the PCA varimax rotated model. The factors were employed as covariates in the ordinal regression models. Multicollinearity in the regression models was tested using the variance inflation factor and odd ratios were calculated. Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05 in all cases. Data availability statement: data are available on doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.20425335.

3. Results

Answers to questions about cultural, fatalistic and psychological factors of the complete set of women pertaining to MG and LG as well as affirmatives in each set (MG+ and LG+) were included in the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1: Summary of answers to questions about cultural, fatalistic, and psychosocial factors in relation to socioeconomic groups: middle economic power (MG) and low economic power (Low group, LG)

* Chi Sqr, p <0.05; ** Chi Sqr, p <0.01; *** Chi Sqr, p <0.001

MG+: number of affirmative answers of middle economic power group (MG)

LG+: number of affirmative answers of low economic power group (LG)

3.1 Cultural items

All women answered the questions referred to how to resolve a problem (Q1a-d) (Table 1), 421/850 (49.5%) preferred to solve a problem by themselves (Q1b) without a significant difference between MG+ and LG+. MG reported talking to their husbands more frequently, while LG preferred to talk to a friend. 539/850 (63.4%) answered the questions referred to their relationship with their husband/couple; an affirmative answer to Q2a (“Do you have a good relationship with your husband/couple?”) was the most frequently selected: 427/539 (79.2%) for MG+ plus LG+, closely followed by Q2c (“Does your husband/couple bring you emotional support?”): 406/539 (75.3%). In both questions, MG+ was higher than LG+ but without a significant difference.

In the next step, affirmative responses to cultural items were analyzed in relation to social group, level of education, Physician visit and Health System (Table 2) a few significant differences were found between MG+ and total MG responses. 94.3% of MG had a high educational level (secondary and higher), which was associated with positive responses to attend their own expenses (Q3b) (p<0.01) and reporting emotional support from their husband/couple (Q2a) (p<0.05).

On the other hand, 80% of MG consulted a Physician, while this percentage was lower in those who had financial help of their husbands/couples (Q2b) (76.7%, p<0.05). In the case of LG, significant differences were found since 58.8% of LG consulted a Physician, and this percentage increased to 72.9% in those women who, when facing a problem talked to a relative (Q1d) (p<0.001), and to 63.2% in those who had a good relationship with their husband/couple (Q2a) (p<0.01). Considering educational level, 49.7% of LG achieved a higher educational level than elementary school; this percentage was lower in those who facing a problem preferred to talk to a friend (Q1c) (43.5%), but higher in those whose husbands/couples financially supported their families (Q2d) (55.4%) (p<0.05, in both cases). Then, affirmative responses were analyzed in relation to mammographic screening variables (Table 3).

In the case of MG, significant differences were obtained in women who, when facing a problem, talked to their husband/couple (Q1a) since the percentage of affirmatives to “every year mammogram” increased from 73.9% (MG) to 78.0% (MG+), (p<0.05). Similarly, analysis of MG in relation to “time since last mammogram” showed that those who reported talking to a relative (Q1d) or having a husband/couple who financially support the family (Q2d) informed that time since last mammogram was lower than two years (92.1% vs 86.5%, p<0.01 and 89.1% vs 86.5%, p<0.05, respectively). In the case of LG, those who when facing a problem talked to a friend (Q1c) showed an increase on affirmatives to “every year mammogram” with respect to total LG: 50.3% to 55.6% (LG+), p<0.05. Fatalistic factors

Table 2 Summarizes fatalistic answers based on the socioeconomic groups. In MG as well as LG, “It dies when the time comes” (Q7) appeared to be the affirmative answer of greatest choice (67.8%), (LG+>MG+), closely followed by “Future is in God’s hands” (Q8) (58.9%), (LG+>MG+, p<0.001). 36% of women prayed to God to resolve a problem (Q10), MG+>LG+ (57.5% versus 42.5%). 238/850 (28.0%) women affirmed “I only go the Doctor when I am ill” (Q6); MG+ and LG+ percentages were similar but LG+/LG were higher than MG+/MG (32.7% versus 24.2%). Interestingly, all the fatalistic questions were answered by the total of women interviewed (850) except “Not believing in God increases the chance of developing breast cancer” (Q4), which was answered by 587/850 (69%), being 266/587 MG and 321/587, LG; only 38 were MG+. Only 31 women (3.6%), affirmed that “Getting a mammogram is having more problems” (Q9), being most of them LG+ (23), while only 11/850 (1.3%) related mammogram to the end of life.

Table 2: Summary of positive answers to cultural, fatalistic, and psychological factors in relation to educational level, health system and physician enrolment. First to each series of answers to cultural, fatalistic and psychosocial items, a row with the general answers of each social group was included to make easier the comparisons. First to each series of answers to cultural, fatalistic and psychosocial items, a row with the general answers of each social group was included to make easier the comparisons.

* Kendall’s tau, p <0.05; ** Kendall’s tau, p <0.01; *** Kendall’s tau, p <0.001

# Chi Sqr, p <0.05; ## Chi Sqr, p <0.01; ### Chi Sqr, p <0.001

Then, fatalistic answers were analyzed in relation to Physician visits, educational level, and to Health System (Table 2). In MG, any correlation between fatalistic items and Health System or Physician visits was found; with respect to educational level, some differences between MG+ and total MG were found. As expected, LG+ for Q6 (“I only go to the Doctor when I am ill”) had a lower Physician visits (38.7%) respect to total LG (58.8%) (p<0.001) and also, LG+ less attended to the non-Public Health System with respect to total LG: 32.8% (LG+) versus 42.3% (LG) (p<0.05).

Table 3: Summary of positive answers to cultural, fatalistic, and psychological items in relation to mammographic variables. First to each series of answers to cultural, fatalistic and psychosocial items, a row with the general answers of each social group was included to make easier the comparisons. First to each series of answers to cultural, fatalistic and psychosocial items, a row with the general answers of each social group was included to make easier the comparisons.

* Kendall’s tau, p <0.05; ** Kendall’s tau, p <0.01; *** Kendall’s tau, p <0.001

# Chi Sqr, p <0.05; ## Chi Sqr, p <0.01; ### Chi Sqr, p <0.001

A significant difference between fatalistic affirmatives in relation to mammogram variables and total MG and LG was only found when Q6 was considered in relation to “Ever performed a mammogram”; MG+ to Q6 was 88.6% versus 95.8% general MG, p<0.001 while LG+ was 60.5% versus general LG, 78.1% (p<0.001) (Table 3). In a few women, in both groups (LG and MG), Q6+ was related with a decrease on performing a mammogram every year; MG+ 56.3% (58/103) versus MG 73.9% (329/445), and LG+ 19% (19/100) versus LG 50.3% (160/318), p<0.001 in both cases. Likewise, in a very small group of women, MG+ and LG+ for Q6 were associated to a longer “time at first mammogram” and to “age at first mammogram” (p<0.001 and p<0.005, respectively), for both groups. In one out of six LG+ for “Ever performed a mammogram”, an association to Q5 (“Do you relate mammogram to end of life”) was found; also, 6.1% (23/379) LG were positive for Q9 “getting a mammogram is having more problems” and 34.3% (130/471) LG were positive for Q10 “Do you pray to God to resolve a problem?”; in both cases a significant association with a lower frequency of mammograms was found (p<0.05 for both).

3.2 Psychosocial Factors

Table 2 Summarizes answers based on the socioeconomic groups (MG and LG). Only 25/823 (3%) affirmed to be embarrassed to have a mammogram, LG+>MG+, while “a little” was the choice for 57/823 (6.9%), mainly MG+. Q12 (“Does the mammogram hurt?”) had also two options: “yes” and “a little”; 206/776 (26.5%) answered “yes”, LG+>MG+, and “a little”: 220/776 (28.4%) affirmatives: MG+>LG+. 714/850 (84%) women answered Q13, 366/714 were middle socioeconomic women and 348, low; the highest percentage of women selected the option b (285/714, 39.9%) which was: “I always give preference to the medical expenses of my children”, being most of them LG+. Only 16/850 women (1.9%) said that they need to ask someone's permission to have a mammogram: 8/471 (1.7%), MG+ while 8/379 (2.1%), LG+.

Following the analysis in relation to some social and health factors (Table 2), in the case of Q13b, MG+ showed a significant decrease percentage respect to general MG in relation to women with a university degree as well as those who attended to non-Public Health System (p<0.01). MG+ to Q11 and Q12 was associated with a lower access to “non-Public Health System” (p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively). On the other hand, LG+ to Q12 and Q13c showed a significant decrease percentage respect to general LG in relation to “Physician visit”. Psychosocial variables showed a very low significant relationship with mammographic screening behavior (Table 3). Only a small group of MG who felt embarrassing the mammogram (Q11) showed a diminished percentage for “every year frequency of mammograms” compared to total MG (p<0.01). It was not found any significant relationship between LG+ for Q11 and Q12 and mammographic variables. Also, in MG+ for Q13b (“I always give preference to the medical expenses of my children”), a significant difference with respect to general MG was only detected for “Ever performed a mammogram”: general MG 451/471 (95.8%) versus MG+ 65/72 (90.3), p<0.05. LG+ for Q13b, showed a significant increased percentage for “age of first mammogram >50 years” with respect to total LG (11.0% versus 8.2%). Also, Q13c (“Not being able to pay for any necessary treatment”) influenced “Ever performed a mammogram”: total LG versus LG+, 78.1% and 67.5%, respectively (p<0.05), and also to performing a mammogram every year: total LG versus LG+, 50.3% and 40.5%, respectively, p<0.05. Other significant differences were found but in a very few women. Noteworthy, only 16/850 (1.9%) women affirmed that they need to ask someone's permission to have a mammogram, 8/471 (1.7%) were MG while 8/379 (2.1% were LG. It was not clear if permission was requested to a relative or at the job.

3.3 Regression analysis

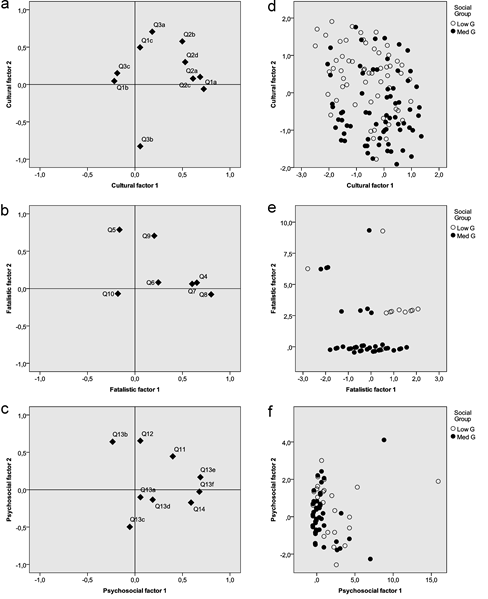

Three regression models were employed to assess the relationship of cultural, fatalistic, and psychological variables with “age at first mammogram”, “frequency of mammograms” and “time since last mammogram” in MG and LG. The variance inflation factor in all regression models showed values between 1 and 2 for all variables, suggesting the absence of multicollinearty. A PCA was conducted to reduce the number of variables and allowed the extraction of three main factors from cultural, fatalistic and psychosocial variables. Cultural factors (C1, C2 and C3) explained 51.3% of cumulative variance (Figure 1a), fatalistic factors (F1, F2 and F3) 54.3% (Figure 1b), while psychological factors (P1, P2 and P3) 45.8% (Figure 1c). Dispersion of MG and LG cases between first and second cultural factors is shown in Figure 1d, while fatalistic in Figure 1e, and psychosocial in Figure 1f. The odds ratio to perform a first mammogram at the age of 40 to 50 years or <40 years was higher in MG, 2.754 (95% CI, 1.805 to 4.200), Wald χ2(1) = 22.109, p < .001. Any significant association between the factors studied and the age at first mammogram was found.

When the variable “frequency of mammograms” was analyzed, we found that performing a mammogram every year was more frequent in women who consulted a Physician, with an odds ratio of 3.521 (95% CI, 2.500 to 4.975), Wald χ2(1) = 51.788, p < .001, and also in women attending non-public hospitals, odds ratio of 1.871 (95% CI, 1.230 to 2.846), Wald χ2(1) = 8.560, p = .003. Also, when the time from last mammogram was analyzed, Physician visits increased the chance of reporting a mammogram in the last year, odds ratio of 2.756 (95% CI, 1.824 to 4.162), Wald χ2(1) = 23.201, p < .001. Women who had a higher educational level reported more frequently a mammogram in the last year, odds ratio of 1.700 (95% CI, 1.085 to 2.663), Wald χ2(1) = 5.358, p = .021. Regression analysis of all women (850) allowed to identify a small group of 15 women (6 MG and 9 LG) in which fatalistic factors were significantly associated with a longer period since last mammogram, odds ratio of 1.400 for F1 (95% CI, 1.137 to 1.723), Wald χ2(1) = 10.038, p = .002, and for F2 an odds ratio of 1.245 (95% CI, 1.034 to 1.499), Wald χ2(1) = 5.327, p = .021. Moreover, women with a high score in P2 (Figure 1f) were less likely to report a mammogram during the last year, odds ratio of 1.296 (95% CI, 1.072 to 1.568), Wald χ2(1) = 7.159, p = .007.

Figure 1: Principal component analysis shows three main factors from cultural (C1, C2, and C3), fatalistic (F1, F2, and F3), and psychosocial (P1, P2, and P3) variables. Cultural factors explained 51.3% of cumulative variance (Figure 1a), fatalistic factors, 54.3% (Figure 1b), while psychosocial factors, 45.8% (Figure 1c). Figure 1 d, e, and f shows dispersion of the cases belonging to both social groups: median economic power women (Med G) and low economic power women (Low G). Figure1d shows dispersion between C1 and C2 while Figure1e between F1 and F2, and Figure 1f between P1 and P2.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Many studies have reported the positive influence of social support on women’s psychological well-being and coping abilities through every stage of breast cancer [10]. In our survey, communication appeared to be an important factor which impact positively on breast cancer screening behavior in both groups; communication seemed to influence positively on mammographic variables mainly to perform a mammogram every year. Other studies have demonstrated that social support would encourage women to breast cancer screening; in this sense, Wagle et al. [11] found social support to be significantly related to the frequency of breast self-examination. Furthermore, numerous reports have documented the role of Physicians on influencing their patients' participation on screening [12]. Another factor which has been largely related with breast cancer screening is fatalism, especially in Latinas; in general, studies have been performed in countries where this group is a minority and are usually compared to “Caucasic”, “Anglo” or “White”. Fatalism has been identified as a dominant belief among Latinos and it has been described to act as a barrier to cancer prevention. Considering fatalistic items, some interesting results appeared in our series. First: “Dies when the time comes” and “Future is in God’s hands” were the two affirmatives present in more than half of the women interviewed, being higher LG+ with respect to MG+ in both cases, but with any significant relationship with mammographic variables. Second: 36% of women prayed to God to solve a problem (MG+>LG+), also without any significant relationship with mammographic variables. Third: all the fatalistic questions were answered by all women interviewed (850), except “Not believing in God increases the chance of developing breast cancer”, which was answered by 587/850 (69%) and only 38 MG affirmed it. Fourth: only 31/850 (3.6%) women said that “Getting a mammogram is having more problems”, and 11/850 (1.3%) related mammogram to the end of life. Results suggest that, although affirmatives to the majority of fatalistic items were present in MG as well as in LG, they seem not to impact on behaviors related to breast cancer screening in most women interviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all research participants who gently answered the Questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

This study was supported by the Instituto Nacional del Cáncer (RM 493/14) and the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (M153 and M192). The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Ethical considerations

This study was in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (Finland, 1964) and further modifications. This research was approved by the Medical Bioethics Committee, Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of La Plata, Argentina, reference No.0800-017399/13-000).

References

- Weedon-Fekjær H, Romundstad PR, Vatten. LJ. Modern mammography screening and breast cancer mortality: population study. BMJ 348 (2014): g3701.

- Cancer Control Programmes in Latin America: Final Declaration of the High–Level Meeting on Multidisciplinary Integrated Cancer Control. International Union Against Cancer (UICC); Geneva, Switzerland (2007, accessed 10 December, 2020).

- Nuche-Berenguer B and Sakellariou D. Socioeconomic Determinants of Participation in Cancer Screening in Argentina: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 9 (2021).

- Croce MV, Cermignani L, Rabassa ME, Segal-Eiras A. Factors associated with breast cancer in an Argentine city. Breast J 24 (2018): 1132-34.

- Di Sibio A, Abriata G, Forman D, Sierra MS. Female breast cancer in Central and South America. Cancer Epidemiol 445 (2016): S110-S120.

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (2020).

- Espinosa de los Monteros K and Gallo LC. The Relevance of Fatalism in the Study of Latinas’ Cancer Screening Behavior: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Behav Med 18 (2011): 310–8.

- Flynn P, Betancourt H, Ormseth S. Culture, emotion and cancer screening: an integrative framework for investigating health behavior. Ann Beh Med 42 (2011): 79-90.

- Cermignani L, Alberdi CG, Demichelis S, Fernández L, Martinucci MM, Zalazar N, Márquez M, Segal-Eiras A, Croce MV. Features related to breast cancer in an entire Argentine rural population. Anticancer Res 34 (2014): 5537-42.

- Katapodi MC, Facione NC, Miaskowski C, Dodd MJ, Waters C. The influence of social support on breast cancer screening in a multicultural community sample. Oncology Nursing Forum 29 (2002): 845–852.

- Wagle A, Komorita NI, Lu ZJ. Social support and breast self-examination. Cancer Nurs 20 (1997): 42-48.

- Shirazi M. The Influence of Social Support and Physician Recommendation on Breast Cancer Screening Practices of Immigrant Iranian Women in the United States. JCPCR 3 (2015):119-122.

Impact Factor: * 5.814

Impact Factor: * 5.814 CiteScore: 2.9

CiteScore: 2.9  Acceptance Rate: 11.01%

Acceptance Rate: 11.01%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks